Abstract

Background

The increasing prevalence of diabetes in Ontario means that there will be growing demand for hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) testing to monitor glycemic control for the management of this chronic disease. Testing HbA1c where patients receive their diabetes care may improve system efficiency if the results from point-of-care HbA1c testing are comparable to those from laboratory HbA1c measurements.

Objectives

To review the correlation between point-of-care HbA1c testing and laboratory HbA1c measurement in patients with diabetes in clinical settings.

Data Sources

The literature search included studies published between January 2003 and June 2013. Search terms included glycohemoglobin, hemoglobin A1c, point of care, and diabetes.

Review Methods

Studies were included if participants had diabetes; if they compared point-of-care HbA1c devices (licensed by Health Canada and available in Canada) with laboratory HbA1c measurement (reference method); if they performed point-of-care HbA1c testing using capillary blood samples (finger pricks) and laboratory HbA1c measurement using venous blood samples within 7 days; and if they reported a correlation coefficient between point-of-care HbA1c and laboratory HbA1c results.

Results

Three point-of-care HbA1c devices were reviewed in this analysis: Bayer's A1cNow+, Bio-Rad's In2it, and Siemens’ DCA Vantage. Five observational studies met the inclusion criteria. The pooled results showed a positive correlation between point-of-care HbA1c testing and laboratory HbA1c measurement (correlation coefficient, 0.967; 95% confidence interval, 0.960–0.973).

Limitations

Outcomes were limited to the correlation coefficient, as this was a commonly reported measure of analytical performance in the literature. Results should be interpreted with caution due to risk of bias related to selection of participants, reference standards, and the multiple steps involved in POC HbA1c testing.

Conclusions

Moderate quality evidence showed a positive correlation between point-of-care HbA1c testing and laboratory HbA1c measurement. Five observational studies compared 3 point-of-care HbA1c devices with laboratory HbA1c assays, and all reported strong correlation between the 2 tests.

Plain Language Summary

Diabetes occurs when the body cannot use glucose normally. It happens because either the pancreas does not make enough insulin (a hormone that controls the level of glucose in the blood) or the body does not respond well to the insulin it makes. High blood glucose levels over a long time cause damage to the heart, eyes, kidneys, and nerves. Checking blood glucose levels often can help doctors choose the right treatment to help keep diabetes in control.

Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) is a test that measures the amount of glucose that has stuck to red blood cells over a 3-month period. It is directly related to a patient's average blood glucose levels. People with diabetes usually go to a laboratory to have their HbA1c tested. However, testing HbA1c in diabetes education centres or doctor's offices may save time and money. There is moderate quality evidence that testing HbA1c where patients receive their diabetes care is comparable to measuring HbA1c in a laboratory.

Background

Overuse, underuse, and misuse of interventions are important concerns in health care and lead to individuals receiving unnecessary or inappropriate care. In April 2012, under the guidance of the Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee's Appropriateness Working Group, Health Quality Ontario (HQO) launched its Appropriateness Initiative. The objective of this initiative is to develop a systematic framework for the ongoing identification, prioritization, and assessment of health interventions in Ontario for which there is possible misuse, overuse, or underuse.

For more information on HQO's Appropriateness Initiative, visit our website at www.hqontario.ca.

Objective of Analysis

The objective of this analysis was to review the correlation between point-of-care hemoglobin A1c (POC HbA1c) testing and laboratory hemoglobin A1c (lab HbA1c) measurement in patients with diabetes in clinical settings.

Clinical Need and Target Population

Description of Disease/Condition

Diabetes is a metabolic disorder resulting from defective insulin production and/or action. There are 2 major types of diabetes: type 1 and type 2. Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disease in which the body's defence system attacks its own insulin-producing cells; type 2 diabetes is characterized by insulin resistance and inadequate insulin production. Type 2 diabetes accounts for over 90% of the diabetes population. Left uncontrolled, the chronic hyperglycemia associated with diabetes contributes to cardiovascular disease and microvascular complications affecting the eyes, kidneys, and nerves. (1) Classic diabetes trials, including the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial for type 1 diabetes and the United Kingdom Prospective Diabetes Study for type 2 diabetes, have demonstrated that optimal glycemic control slows the onset and progression of diabetes-related complications. (2–4)

Hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) is a marker of long-term glycemic control, and it has been widely used to guide treatment decisions in clinical practice. Its value reflects average blood glucose concentration over the preceding 3 months. (5) It is recommended that patients with diabetes have HbA1c tested every 3 to 6 months to assess glycemic control. (6)

Ontario Prevalence

In 2012, Statistics Canada reported a prevalent diabetes population of 770,410 in Ontario. (7) This figure is expected to increase in parallel with the upward trend of obesity and the aging population.

Technology/Technique

Point-of-care testing refers to diagnostic testing at or near the site of patient care. (8) POC HbA1c testing is an alternative to lab HbA1c measurement, and it has several potential advantages. First, it provides rapid test results following blood collection, to expedite medical decision-making. Second, it may improve health system efficiency and be convenient for patients, because fewer visits to laboratories or physician's offices would be needed. Third, it may improve access to HbA1c measurement for patients in underserved populations (e.g., rural or remote communities).

POC HbA1c requires a finger-prick blood sample. This capillary blood sample is applied to a reagent cartridge, which is then inserted into a desktop analyzer; HbA1c is quantified and reported in 5 to 10 minutes. Point-of-care devices use different methods to measure HbA1c, including boronate affinity chromatography and immunoassay. (9)

Similar to lab HbA1c assays, POC HbA1c devices must be certified by the United States National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program (NGSP), and the results must be traceable to the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial Reference Method. (10) The certification process involves comparing the POC HbA1c values of 40 patient samples with those from a Secondary Reference Laboratory. Currently, the bias criteria for 37 out of 40 results are within 7% of the NGSP Secondary Reference Laboratory findings, over an HbA1c range of 4% to 10% (beginning in January 2014, the bias criteria will be tightened to within 6%). (11) Device certification is effective for 1 year, and is specific to the particular lot of reagent and the device used. (12) Point-of-care HbA1c devices are waived under Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments (i.e., users are not required to participate in proficiency testing).

In 2010, Lenters-Westra et al (13) used the Clinical Laboratory Standard Institute protocols to evaluate the analytical performance of 8 POC HbA1c devices in venous blood samples of patients with diabetes. They reported that at the time of writing, only 2 POC HbA1c devices—DCA Vantage from Siemens and Afinion from Axis-Shield (not licensed by Health Canada)—met the criteria: that is, a coefficient of variation of < 3% and error criteria1 of ± 0.85% as specified by the NGSP (in January 2010, the error criteria were lowered to ± 0.75%). (14) However, since experienced technologists at manufacturers’ sites performed the certification under ideal conditions, the results of this study may not reflect the performance of these devices in clinical settings.

Ontario Context

The current standard of care in Ontario is that patients with diabetes go to community laboratories or hospitals for HbA1c measurement, usually prior to their physician visit. POC HbA1c devices are being used in selected diabetes education centres, community health centres, and doctor's offices, funded by their operating budgets.

The prevalence of POC HbA1c testing in Ontario is unclear. However, considering the increasing prevalence of diabetes, there will be a growing need for HbA1c testing to monitor glycemic control. POC HbA1c testing may improve system efficiency if the results from point-of-care devices are comparable to those from laboratory assays. Therefore, Health Quality Ontario chose to compare the correlation between POC HbA1c and lab HbA1c measurement in clinical settings.

Regulatory Status

Six POC HbA1c devices are licensed by Health Canada as class-3 devices for quantitative determination of HbA1c from capillary or venous whole blood. The manufacturer information for these devices is presented in Table 1.

Table 1:

Manufacturer Information for POC HbA1c Devices Licensed for Use in Canada

| Manufacturer Information | A1c Now Self-Check at Home A1c System | A1c Now+ | DCA 2000 Analyzer System | DCA Vantage Analyzer | In2it (I) System | Smart Direct HbA1c Analyzer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturer | Bayer Healthcare LLC | Bayer Healthcare LLC | Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Inc | Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Inc | Bio-Rad Laboratories Deeside | Diazyme Laboratories |

| Licence number | 84541 | 65484 | 1990 | 76034 | 80662 | 88752 |

| Issue Date | November 2010 | July 2008 | March 1999 | January 2008 | September 2009 | April 2012 |

| Remark | — | — | Unavailable in Canada | — | — | Unavailable in Canada |

Abbreviation: POC HbA1c, point-of-care hemoglobin A1c.

The operating characteristics of the 3 POC HbA1c devices that are available for use in Canada are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2:

Characteristics of POC HbA1c Devices Available for Use in Canada

| Characteristic | A1c Now+ | DCA Vantage Analyzer | In2it (I) System |

|---|---|---|---|

| Manufacturer | Bayer Healthcare LLC | Siemens Healthcare Diagnostics Inc | Bio-Rad Laboratories Deeside |

| Method | Immunoassay | Latex agglutination inhibition immunoassay | Boronate-affinity chromatography |

| Blood sample | 5 μL (capillary or venous) | 1 μL (capillary or venous) | 10 μL (capillary or venous) |

| Time for results | 5 minutes | 6 minutes | 10 minutes |

| Interference with abnormal hemoglobin variants (15) | HbC, HbS, HbF − 10–15% | HbC, HbE, HbF − 10–15% | HbF − 10% |

| NGSP-certified (16) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| CLIA waived | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Other characteristics | Same device as A1c Now, with more test cartridges in the kit | Successor of DCA 2000 | N/A |

Abbreviation: CLIA, Clinical Laboratory Improvement Amendments; HbC, hemoglobin C; HbE, hemoglobin E; HbF, hemoglobin F; HbS, hemoglobin S; NGSP, National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program; POC HbA1c, point-of-care hemoglobin A1c.

Evidence-Based Analysis

Research Question

What is the correlation between POC HbA1c testing and lab HbA1c measurements in patients with diabetes in clinical settings?

Research Methods

Literature Search

Search Strategy

A literature search was performed on June 17, 2013, using Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid MEDLINE In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations, Ovid Embase, EBSCO Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and EBM Reviews, for studies published from January 1, 2003, to June 17, 2013. (Appendix 1 provides details of the search strategies.) Abstracts were reviewed by a single reviewer and, for those studies meeting the eligibility criteria, full-text articles were obtained. Reference lists were also examined for any additional relevant studies not identified through the search.

Inclusion Criteria

English-language full-text publications

published between January 1, 2003, and June 17, 2013

randomized controlled trials, observational studies, systematic reviews, and meta-analyses

patients with type 1 or type 2 diabetes of all ages

studies comparing POC HbA1c devices (licensed by Health Canada and available on the Canadian market) with lab HbA1c measurement (reference standard)

POC HbA1c testing with capillary blood samples from finger pricks and lab HbA1c measurement with venous blood samples within 7 days

Exclusion Criteria

studies that included participants without diabetes

studies that used older generation of POC HbA1c devices (e.g., DCA 2000 has been replaced by DCA Vantage, and is no longer on Canadian market)

studies that used finger-prick capillary blood samples for both POC HbA1c and lab HbA1c measurements

studies that used venous whole blood samples for both POC HbA1c and lab HbA1c measurements

studies that measured POC HbA1c and lab HbA1c more than 7 days apart

studies that did not compare POC HbA1c and lab HbA1c (reference standard)

Outcome of Interest

correlation coefficient between POC HbA1c and lab HbA1c measurements

Statistical Analysis

Fisher transformation was performed on correlation coefficients (r) for a bivariate normal distribution using the formula z = 0.5* ln ((1 + r)/(1 – r)), where z denoted the Fisher-transformed r. Standard error for the r was derived from 1/(√n − 3), where n denoted the sample size. The z then underwent meta-analysis using Stata 12 (Stata Corporation, College Station, Texas). Finally, the summary estimate of z was back-transformed to normal scale using the formula r = (exp (2z) − 1)/(exp (2z) + 1). (17)

Quality of Evidence

The quality of evidence for each study was examined using the revised Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies (QUADAS-2) tool. (18)

The quality of the body of evidence for each outcome was examined according to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group criteria. (19) The overall quality was determined to be high, moderate, low, or very low using a step-wise, structural methodology.

Study design was the first consideration; for diagnostic tests, cross-sectional or cohort studies in patients with diagnostic uncertainty and direct comparison of test results with an appropriate reference standard are considered high quality. (20) Five additional factors—risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias—were then taken into account. Limitations in these areas resulted in downgrading the quality of evidence. Finally, 3 main factors that may raise the quality of evidence were considered: the large magnitude of effect, the dose response gradient, and any residual confounding factors. (19) For more detailed information, please refer to the latest series of GRADE articles. (19)

As stated by the GRADE Working Group, the final quality score can be interpreted using the following definitions:

| High | High confidence in the effect estimate—the true effect lies close to the estimate of the effect |

| Moderate | Moderate confidence in the effect estimate—the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but may be substantially different |

| Low | Low confidence in the effect estimate—the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect |

| Very Low | Very low confidence in the effect estimate—the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of effect |

Results of Evidence-Based Analysis

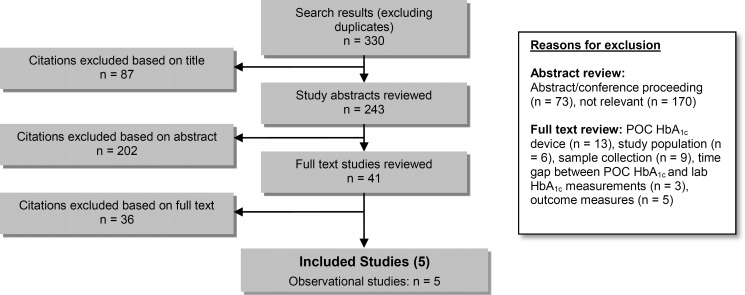

The database search yielded 330 citations published between January 1, 2003, and June 17, 2013 (with duplicates removed). Articles were excluded based on information in the title and abstract. The full texts of potentially relevant articles were obtained for further assessment. Figure 1 shows the breakdown of when and for what reason citations were excluded from the analysis.

Figure 1: Citation Flow Chart.

Abbreviations: lab HbA1c, laboratory hemoglobin A1c; POC HbA1c, point-of-care hemoglobin A1c.

Five observational studies met the inclusion criteria. (21–25) The reference lists of the included studies were hand-searched to identify other relevant studies, but with no additional citations were included.

Study authors were contacted for additional information: correlation coefficients, (22;25) time interval between POC HbA1c and lab HbA1c measurements, (25) and whether study participants had diabetes. (24)

For each included study, the study design was identified and is summarized below in Table 3, a modified version of a hierarchy of study design by Goodman. (26)

Table 3:

Body of Evidence Examined According to Study Design

| Study Design | Number of Eligible Studies |

|---|---|

| RCTs | |

| Systematic review of RCTs | |

| Large RCT | |

| Small RCT | |

| Observational Studies | |

| Systematic review of non-RCTs with contemporaneous controls | |

| Non-RCT with non-contemporaneous controls | 5 |

| Systematic review of non-RCTs with historical controls | |

| Non-RCT with historical controls | |

| Database, registry, or cross-sectional study | |

| Case series | |

| Retrospective review, modelling | |

| Studies presented at an international conference | |

| Expert opinion | |

| Total | 5 |

Abbreviation: RCT; randomized controlled trial.

Correlation Between POC HbA1c and Lab HbA1c

Five cross-sectional studies (21–25) that compared the correlation of POC HbA1c testing with lab HbA1c measurement met the inclusion criteria. All of the included studies measured POC HbA1c using capillary blood samples obtained from a finger prick, and compared this value with the lab HbA1c result measured from venous blood samples. Table 4 summarizes the characteristics of the included studies. The quality of the evidence was moderate (Appendix 2).

Table 4:

Characteristics of Included Studies

| Author, Year | Study Sample, n | Country | POC HbA1c Device | Reference Test | Time Between POC HbA1c and Lab HbA1c Tests | Industry Sponsorship |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arrendale et al, 2008 (21) | 70 | USA | A1c Now+ | Standard lab HbA1c assays | Within 7 days | — |

| Leca et al, 2012 (22) | 100 | France | DCA Vantage | Tosch high-performance liquid chromatography | Within 2 hours | — |

| Leal et al, 2009 (23) | 47 | USA | A1c Now+ | Standard lab HbA1c assays | Within 4 days | Bayer |

| Martin et al, 2010 (24) | 100 | France | In2it | Variant II high-performance liquid chromatography | Within 6 hours | Bio-Rad |

| Yeo et al, 2009 (25) | 80 | Singapore | In2it | Cobas c501 latex-enhanced competitive turbidimetric immunoassay | Within 5–15 minutes | — |

Abbreviations: HbA1c, hemoglobin A1c; lab HbA1c, laboratory hemoglobin A1c; POC HbA1c, point-of-care hemoglobin A1c.

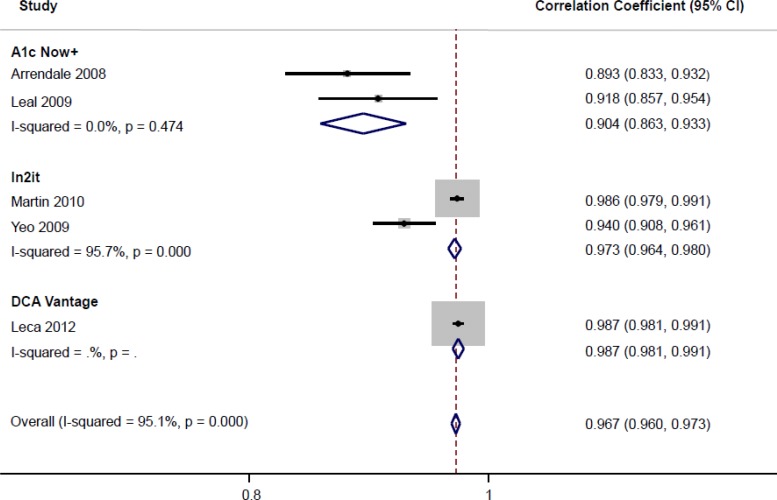

The correlation coefficients (r) of these 5 studies comparing POC HbA1c testing with lab HbA1c measurement were pooled (Figure 2). Although there was a high correlation between POC HbA1c testing and lab HbA1c measurements among all included studies, there was also a high degree of statistical heterogeneity associated with this analysis. In an attempt to explore the source of the heterogeneity, the meta-analysis was stratified by POC HbA1c device. Between the 2 studies evaluating Bayer's A1cNow+, the pooled correlation coefficient with lab HbA1c was high, and there was no statistical heterogeneity. For the 2 studies on Bio-Rad's In2it, the pooled correlation coefficient was also high, but with significant statistical heterogeneity. One of the potential sources of heterogeneity could be the different lab HbA1c reference standards used in these 2 studies.

Figure 2: Included Studies Comparing POC HbA1c With Lab HbA1c.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; lab HbA1c, laboratory hemoglobin A1c; POC HbA1c, point-of-care hemoglobin A1c.

Limitations

This analysis showed a positive correlation between POC HbA1c testing using capillary blood samples and lab HbA1c measurement using venous blood samples, suggesting a strong agreement between these measurements. However, the results should be interpreted with caution, mainly due to the limitations of the included studies.

It is essential to compare the index test (POC HbA1c) to a standardized and validated reference test (lab HbA1c) to establish the validity of the index test. Laboratory assays employ different biochemical principles to measure HbA1c, including high-performance liquid chromatography based on charge differences of the hemoglobin fractions, and immunoassay based on structural differences. Of the 2 included studies on A1c Now+ (21;23), only “standard central laboratory assays” were reported. The 2 studies on In2it used different reference standards: high-performance liquid chromatography (24) and latex-enhanced competitive turbidimetric immunoassay. (25) Compared to the results from Yeo et al, (25) Martin et al (24) reported a stronger correlation between In2it and the reference standard, both of which were chromatography-based assays.

Correlation coefficient was chosen as the outcome of interest for this review because it was the most commonly reported measure of analytical performance in the literature. Very few studies reported the sensitivity and specificity of POC HbA1c against lab HbA1c. Bland-Altman plot is a preferred method for evaluating agreement between 2 analytical methods. It plots the average (x-axis) against the difference between 2 measurements (y-axis) to show the systematic difference. (27) However, only 2 of the included studies showed a Bland-Altman plot, and both reported a positive bias for POC HbA1c compared to lab HbA1c. (24;25)

A potential bias identified was uncertainty about how participants were selected for the studies, (e.g., randomization, stratification, or consecutive enrolment in a given time period). Another potential source of bias was that POC HbA1c testing involves multiple steps in preparing the blood samples before measurement, and this may increase the risk of measurement errors. The precision of the measurement as measured by coefficient of variation was not consistently reported in the literature.

Although POC HbA1c devices are certified by the NGSP to meet requirements for analytical performance and traceability of results, bias (i.e., difference in the absolute value between POC HbA1c and lab HbA1c measurements) exists. Since the intended use of POC HbA1c for this analysis was for monitoring glycemic control in diabetes (rather than diagnosing diabetes), misclassification was unlikely to be a concern. However, if the POC HbA1c value was close to a threshold at which therapeutic change would be warranted, (e.g., 8.5%), any positive or negative bias may lead to inappropriate treatment decisions. Still, advice on lifestyle modification or dosage change in medications would be unlikely to cause immediate life-threatening harm if patients were monitored closely and had another HbA1c test in 3 months.

Conclusions

Moderate quality evidence showed a positive correlation between POC HbA1c testing and lab HbA1c measurement. Five observational studies compared 3 POC HbA1c devices with lab HbA1c assays, and all reported strong correlation between the 2 tests.

Acknowledgements

Editorial Staff

Jeanne McKane, CPE, ELS(D)

Medical Information Services

Corinne Holubowich, BEd, MLIS

Kellee Kaulback, BA(H), MISt

Expert Advisory Panel on Community-Based Care for Adult Patients With Type 2 Diabetes

| Panel Members | Affiliation(s) | Appointment(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Co-Chairs | ||

| Dr Baiju Shah | Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences University of Toronto | Staff Physician, Division of Endocrinology Scientist, ICES Associate Professor |

| Dr David Tannenbaum | Mount Sinai Hospital Ontario College of Family Physicians University of Toronto | Chief of Department of Family & Community Medicine Past-President, OCFP Associate Professor |

| Endocrinologist | ||

| Dr Harpreet Bajaj | Ontario Medical Association LMC Endocrinology Centre | Tariff Chairman, Section of Endocrinology |

| Dr Alice Cheng | Trillium Health Partners St. Michael's Hospital | Endocrinologist, Division of Endocrinology and Metabolism |

| Dr Janine Malcolm | Ottawa Hospital Ottawa Health Research Institute | |

| Nephrologist | ||

| Dr Sheldon Tobe | Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre Canadian Cardiovascular Harmonized National Guidelines Endeavor | Associate Scientist Co-Chair, C-CHANGE |

| Family Physician | ||

| Dr Robert Algie | Fort Frances Family Health Team | Lead Physician |

| Dr J Robin Conway | Perth and Smiths Falls Community Hospitals Canadian Centre for Research on Diabetes | Family Physician (Diabetes Care) |

| Dr Lee Donohue | Ontario Medical Association | Health Policy Chair, Section of General and Family Practice |

| Dr Dan Eickmeier | Huron Community Family Health Team | |

| Dr Stewart B. Harris | Western University | Professor, Department of Family Medicine |

| Dr Warren McIsaac | Mount Sinai Hospital University of Toronto | |

| Nurse Practitioner | ||

| Betty Harvey | St. Joseph's Healthcare Hamilton | Clinical Nurse Specialist/Nurse Practitioner, Primary Care Diabetes Support Program |

| Registered Nurse | ||

| Brenda Dusek | Registered Nurses Association of Ontario | Program Manager, International Affairs & Best Practice Guideline Centre |

| Registered Nurse/Certified Diabetes Educator | ||

| Bo Fusek | Hamilton Health Sciences Centre | Diabetes Care and Research Program |

| Melissa Gehring | St. Joseph's Healthcare Hamilton | Diabetes Research Coordinator |

| Amanda Mikalachki | St. Joseph's Healthcare Hamilton | |

| Registered Dietitian/Certified Diabetes Educator | ||

| Pamela Colby | St. Joseph's Healthcare Hamilton Brescia University College, Western University | |

| Stephanie Conrad | Weeneebayko Diabetes Health Program | |

| Registered Dietitian | ||

| Stacey Horodezny | Trillium Health Partners | Team Leader, Diabetes Management Centre & Centre for Complex Diabetes Care |

| Lisa Satira | Mount Sinai Hospital | |

| Pharmacist | ||

| Lori MacCallum, PharmD | Banting and Best Diabetes Centre, University of Toronto | Program Director, Knowledge Translation and Optimizing Care Models Assistant Professor, Leslie Dan Faculty of Pharmacy |

| Clinical Pharmacist | ||

| Christine Papoushek, PharmD | Toronto Western Hospital University of Toronto | Pharmacotherapy Specialist, Department of Family Medicine |

| Community Pharmacist | ||

| Mike Cavanagh | Kawartha Lakes Pharmacy Ontario Pharmacists Association | |

| Economic Modelling Specialist | ||

| Meredith Vanstone, PhD | McMaster University | Post-doctoral Fellow, Centre for Health Economics and Policy Analysis |

| Epidemiologist/Scientist | ||

| Daria O'Reilly, PhD | McMaster University | Assistant Professor |

| Knowledge Translation/Delivery of Diabetes Self-Management Education | ||

| Enza Gucciardi, PhD | Ryerson University | Associate Professor, School of Nutrition |

| Bioethicist | ||

| Frank Wagner | Toronto Central CCAC University of Toronto | Assistant Professor, Department of Family and Community Medicine |

| Ontario Cardiac Care Network Representative | ||

| Kori Kingsbury | Cardiac Care Network | Chief Executive Officer |

| Heart and Stroke Foundation Representative/Registered Dietitian | ||

| Karen Trainoff | Ontario Heart and Stroke Foundation | Senior Manager, Health Partnerships |

| Centre for Complex Diabetes Care Representative/Registered Dietitian | ||

| Margaret Cheung | Trillium Health Partners Mississauga Hospital | Clinical Team Leader |

| Community Care Access Centre Representative | ||

| Dorota Azzopardi | Central West CCAC | Client Services Manager – Quality Improvement, Chronic – Complex and Short Stay |

| General Internal Medicine/Health Services Research | ||

| Dr Jan Hux | Canadian Diabetes Association | Chief Scientific Officer |

Appendices

Appendix 1: Literature Search Strategies

Search date: June 12, 2013

Databases searched: Ovid MEDLINE, MEDLINE In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations, EMBASE, All EBM Databases, CINAHL

Q: Point-of-care hemoglobin A1c testing

Limits: 2003–current; English

Filters: none

Database: EBM Reviews - Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2005 to April 2013, EBM Reviews - ACP Journal Club 1991 to May 2013, EBM Reviews - Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects 2nd Quarter 2013, EBM Reviews - Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials May 2013, EBM Reviews - Cochrane Methodology Register 3rd Quarter 2012, EBM Reviews - Health Technology Assessment 2nd Quarter 2013, EBM Reviews - NHS Economic Evaluation Database 2nd Quarter 2013, Embase 1980 to 2013 Week 23, Ovid MEDLINE(R) 1946 to May Week 5 2013, Ovid MEDLINE(R) In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations June 11, 2013

Search Strategy:

| # | Searches | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | exp Hemoglobin A, Glycosylated/ use mesz,acp,cctr,coch,clcmr,dare,clhta,cleed | 24767 |

| 2 | exp hemoglobin A1c/ use emez | 37027 |

| 3 | (A1c or HbA1c* or h?emoglobin A1c* or glycated h?emoglobin* or glycosylated h?emoglobin* or glycoh?emoglobin*).mp. | 91304 |

| 4 | or/1–3 | 100156 |

| 5 | exp Point-of-Care Systems/ use mesz,acp,cctr,coch,clcmr,dare,clhta,cleed | 6905 |

| 6 | exp “point of care testing”/ use emez | 3615 |

| 7 | (point of care or POC or PoCT or near patient test* or bed?side* or DCA Vantage Analyzer* or Smart Direct HbA1c Analyzer* or A1cNow*).mp. | 58425 |

| 8 | or/5–7 | 58425 |

| 9 | 4 and 8 | 490 |

| 10 | limit 9 to english language [Limit not valid in CDSR,ACP Journal Club,DARE,CCTR,CLCMR; records were retained] | 468 |

| 11 | limit 10 to yr=“2003 -Current” [Limit not valid in DARE; records were retained] | 438 |

| 12 | remove duplicates from 11 | 290 |

CINAHL

| # | Query | Results |

|---|---|---|

| S1 | (MH “Hemoglobin A, Glycosylated”) | 8,578 |

| S2 | (A1c or HbA1c* or h?emoglobin A1c* or glycated h?emoglobin* or glycosylated h?emoglobin* or glycoh?emoglobin*) | 12,219 |

| S3 | S1 OR S2 | 12,219 |

| S4 | (MH “Point-of-Care Testing”) | 2,048 |

| S5 | (point of care or POC or PoCT or near patient test* or bed?side* or DCA Vantage Analyzer* or Smart Direct HbA1c Analyzer* or A1cNow*) | 5,515 |

| S6 | S4 OR S5 | 5,515 |

| S7 | S3 AND S6 | 103 |

| S8 | S3 AND S6 Limiters - Published Date from: 20030101–20131231; English Language | 96 |

Appendix 2: Evidence Quality Assessment

Table A1:

GRADE Evidence Profile for Comparison of POC HbA1c and Lab HbA1c

| Number of Studies (Design) | Risk of Bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication Bias | Upgrade Considerations | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Correlation Between POC HbA1c and Lab HbA1c | |||||||

| 5 (observational) | Serious limitations (−1)a | No serious limitations | No serious limitationsb | No serious limitations | Undetected | None | ⊕⊕⊕ Moderate |

Abbreviations: lab HbA1c, laboratory hemoglobin A1c; POC HbA1c, point-of-care hemoglobin A1c.

There was uncertainty in the process of patient selection in most studies, as well as the use of different laboratories for analyses.

In the meta-analysis stratified by POC HbA1c device, there was significant heterogeneity between the studies on In2it, which may have been related to the different reference standards used in these trials. Martin et al (24) reported a stronger correlation between In2it and the reference standard, both of which were based on chromatography; the reference standard used by Yeo et al (25) was an immunoassay.

Table A2:

Risk of Bias Among Observational Trials for the Comparison of POC HbA1c and Lab HbA1c (QUADAS-2)

| Author, Year | Selection of Participants | Index Test | Reference Standard | Flow and Timing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arrendale et al, 2008 (21) | High riska | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Leca et al, 2012 (22) | High riska | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Leal et al, 2009 (23) | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk | High riskb |

| Martin et al, 2010 (24) | High riska | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

| Yeo et al, 2009 (25) | High riska | Low risk | Low risk | Low risk |

Abbreviations: lab HbA1c, laboratory hemoglobin A1c; POC HbA1c, point-of-care hemoglobin A1c; QUADAS-2, revised Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies.

Unclear if participants were selected randomly or consecutively.

Some blood samples were sent to a different laboratory for analysis.

Footnotes

95% confidence interval [CI] of the difference between POC HbA1c and lab HbA1c measurements.

References

- (1).Forbes JM, Cooper ME. Mechanisms of diabetic complications. Physiol Rev. 2013. Jan; 93(1): 137–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).White NH, Sun W, Cleary PA, Danis RP, Davis MD, Hainsworth DP, et al. Prolonged effect of intensive therapy on the risk of retinopathy complications in patients with type 1 diabetes mellitus: 10 years after the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008. Dec; 126(12): 1707–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Albers JW, Herman WH, Pop-Busui R, Feldman EL, Martin CL, Cleary PA, et al. Effect of prior intensive insulin treatment during the Diabetes Control and Complications Trial (DCCT) on peripheral neuropathy in type 1 diabetes during the Epidemiology of Diabetes Interventions and Complications (EDIC) Study. Diabetes Care. 2010. May; 33(5): 1090–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Holman RR, Paul SK, Bethel MA, Matthews DR, Neil HA. 10-year follow-up of intensive glucose control in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2008. Oct 9; 359(15): 1577–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Gallagher EJ, Le RD, Bloomgarden Z. Review of hemoglobin A(1c) in the management of diabetes. J Diabetes. 2009. Mar; 1(1): 9–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Canadian Diabetes Association Clinical Practice Guidelines Expert Committee. Canadian Diabetes Association 2013 clinical practice guidelines for the prevention and management of diabetes in Canada (Internet). Ottawa, ON: Canadian Diabetes Association; 2013. (cited 2013 Sep 19). 212 p. Available from: http://guidelines.diabetes.ca/App_Themes/CDACPG/resources/cpg_2013_full_en.pdf [Google Scholar]

- (7).Statistics Canada. Diabetes by sex, provinces and territories (Internet). Ottawa (ON): Government of Canada; 2013. (cited 2013 Sep 19). Available from: http://www.statcan.gc.ca/tables-tableaux/sum-som/l01/cst01/health54a-eng.htm [Google Scholar]

- (8).Kost GJ. Guidelines for point-of-care testing. Improving patient outcomes. Am J Clin Pathol. 1995. Oct;104 (4 Suppl 1): S111–S127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).John WG, Mosca A, Weykamp C, Goodall I. HbA1c standardisation: history, science and politics. Clin Biochem Rev. 2007. Nov; 28(4): 163–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Sacks DB, Arnold M, Bakris GL, Bruns DE, Horvath AR, Kirkman MS, et al. Guidelines and recommendations for laboratory analysis in the diagnosis and management of diabetes mellitus. Clin Chem. 2011. Jun;57 (6): e1–e47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program. NGSP News (Internet). Missouri: National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program; 2013. (cited 2013 Sep 19). Available from: http://www.ngsp.org/news.asp [Google Scholar]

- (12).National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program. Obtaining certification (Internet). Missouri: National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program; 2013. (cited 2013 Sep 19). 7 p. Available from: http://www.ngsp.org/cert/Manufinfo1113.pdf [Google Scholar]

- (13).Lenters-Westra E, Slingerland RJ. Six of eight hemoglobin A1c point-of-care instruments do not meet the general accepted analytical performance criteria. Clin Chem. 2010. Jan; 56(1): 44–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program. Meeting of the National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program Steering Committee minutes (Internet). Missouri: National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program; 2011. (cited 2013 Sep 19). 9 p. Available from: http://www.ngsp.org/docs/SC2011.pdf [Google Scholar]

- (15).National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program. HbA1c Assay Interferences (Internet). Missouri: National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program; 2013. (cited 2013 Sep 19). Available from: http://www.ngsp.org/interf.asp [Google Scholar]

- (16).National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program. List of NGSP certified methods (Internet). Missouri: National Glycohemoglobin Standardization Program; 2013. (cited 2013 Sep 19). 17 p. Available from: http://www.ngsp.org/docs/methods.pdf [Google Scholar]

- (17).Cox NJ. Speaking Stata: Correlation with confidence, or Fisher's z revisited (Internet). Texas: StataCorp LP; 2008. (cited 2013 Sep 19). Available from: http://www.stata-journal.com/sjpdf.html?articlenum=pr0041

- (18).Whiting PF, Rutjes AW, Westwood ME, Mallett S, Deeks JJ, Reitsma JB, et al. QUADAS-2: a revised tool for the quality assessment of diagnostic accuracy studies. Ann Intern Med. 2011. Oct 18; 155(8): 529–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Schunemann HJ, Tugwell P, Knottnerus A. GRADE guidelines: a new series of articles in the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011. Apr; 64(4): 380–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Schunemann HJ, Oxman AD, Brozek J, Glasziou P, Jaeschke R, Vist GE, et al. Grading quality of evidence and strength of recommendations for diagnostic tests and strategies. BMJ. 2008. May 17; 336(7653): 1106–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Arrendale JR, Cherian SE, Zineh I, Chirico MJ, Taylor JR. Assessment of glycated hemoglobin using A1CNow+ point-of-care device as compared to central laboratory testing. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2008. Sep; 2(5): 822–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Leca V, Ibrahim Z, Lombard-Pontou E, Maraninchi M, Guieu R, Portugal H, et al. Point-of-care measurements of HbA(1c): simplicity does not mean laxity with controls. Diabetes Care. 2012. Dec;35 (12): e85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Leal S, Soto-Rowen M. Usefulness of point-of-care testing in the treatment of diabetes in an underserved population. J Diabetes Sci Technol. 2009. Jul; 3(4): 672–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Martin M, Leroy N, Sulmont V, Gillery P. Evaluation of the In2it analyzer for HbA1c determination. Diabetes Metab. 2010. Apr; 36(2): 158–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Yeo CP, Tan CH, Jacob E. Haemoglobin A1c: evaluation of a new HbA1c point-of-care analyser Bio-Rad in2it in comparison with the DCA 2000 and central laboratory analysers. Ann Clin Biochem. 2009. Sep; 46 (Pt 5): 373–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).Goodman C. Literature searching and evidence interpretation for assessing health care practices. Stockholm, Sweden: Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health Care; 1996. 81 p. SBU Report No. 119E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (27).Bland JM, Altman DG. Statistical methods for assessing agreement between two methods of clinical measurement. Lancet. 1986. Feb 8; 1(8476): 307–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]