Abstract

Objectives:

To determine the prevalence of habitual snoring among a sample of middle-aged Saudi adults, and its potential predictors.

Methods:

A cross-sectional study was conducted from March 2013 until June 2013 in randomly selected Saudi Schools in Jeddah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. The enrolled subjects were 2682 school employees (aged 30-60 years, 52.1% females) who were randomly selected and interviewed. The questionnaire used for the interview included: the Wisconsin Sleep Questionnaire to assess for snoring, medical history, and socio-demographic data. Anthropometric measurements and blood pressure readings were recorded using standard methods.

Results:

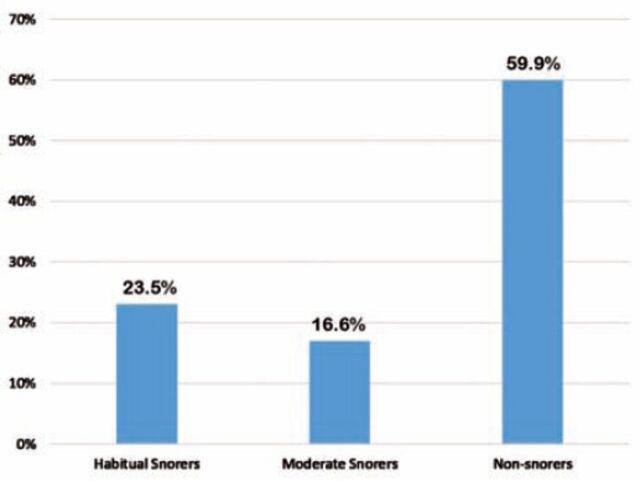

Forty percent of the 2682 enrolled subjects were snorers: 23.5% were habitual snorers, 16.6% were moderate snorers, and 59.9%, were non-snorers. A multivariate analysis revealed that independent predictors of snoring were ageing, male gender, daytime sleepiness, hypertension, family history of both snoring and obstructive sleep apnea, water-pipe smoking, and consanguinity.

Conclusion:

This study shows that snoring is a common condition among the Saudi population. Previously reported risk factors were reemphasized but consanguinity was identified as a new independent predictive risk factor of snoring. Exploring snoring history should be part of the clinical evaluation.

Snoring is defined as a harsh buzzing noise produced by vibration of the soft palate and pillars of the oropharyngeal inlet, primarily with inspiration during sleep. Habitual snoring (HS) is defined as the presence of loud snoring at least 3 nights per week, and is strongly associated with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).1,2 Even in the absence of OSA, HS is associated with health and social consequences including sleep fragmentation, family discord, excessive daytime sleepiness, and more seriously, the development of systemic hypertension in individuals aged <50 years.3 However, many individuals regard HS as a benign and a common behavior; moreover, physicians often disregard snoring as a disorder in their clinical practice. Such denial may lead to delayed recognition and management of OSA.1 Loud snorers have a 40% greater chance of developing hypertension, 34% greater chance of developing heart attack, and 67% greater chance of developing stroke, compared to non-snorers after adjustments for age, gender, body mass index, diabetes, level of education, smoking, and alcohol consumption.4 More recently, heavy snoring has been independently associated with carotid atherosclerosis and treating it was suggested as an important goal in prevention of stroke.5 There have been many international epidemiological studies to establish the prevalence of habitual snoring. Habitual snoring was reported to affect 35.7% of American,2 37.2% of Polish,6 35% of Spanish,7 19.6% of Chinese,8,9 17.3% of Korean,10 and 25.6% of Indian populations.20 The main reported risk factors were aging, male gender, obesity, and smoking. However, very limited data is available on the prevalence and impact of HS in the Middle Eastern countries. A limited study on Saudi health care workers reported HS in only 5.4%.11 Another primary health care clinics based study found a snoring prevalence of 52.3% in Saudi males, and 40.8% in Saudi females.12,13 Therefore, we conducted the current study to assess the actual prevalence and risk factors predictive of HS in a cohort of subjects in Saudi Arabia. Our results will be used to assess the size of the problem and increase awareness of this health disorder among health care professions, so that sleep disordered breathing can be effectively diagnosed and treated.

Methods

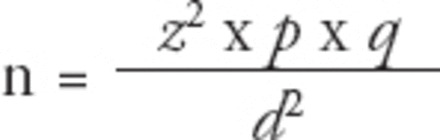

A cross-sectional study was conducted from March 2013 until June 2013 in randomly selected Saudi schools, Jeddah, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia as part of a large ongoing study on OSA among Saudi residents. The target population was Saudi school employees. Such a target population was selected since it has employees with comparative genders, socioeconomic status, and relatively easy to contact and to recruit. A list of the city of Jeddah schools was obtained from the Ministry of Education; it showed 1119 schools located in 4 regions of the city (south, northwest, east, and central). A multistage stratified random sampling technique was then employed to first select 129 schools according to educational level, gender, and the type of school. Subjects were subsequently selected if they were Saudi employees aged ≥30 but ≤60 years, who resided in the western region of the country. The study sample size was calculated using the following formula:14

Where n is the minimum sample size, and z is the constant 1.96. As there was no recent study on the prevalence of snoring among Saudi employees in Jeddah, we used a most conservative estimate of 50%; thus, p=0.5 and q=1-p=0.5. Using this technique, we determined a sample size of 600 subjects was needed to achieve a precision of ±4% with a 95% confidence interval (CI). This minimum number was exceeded by our enrollment of 2682 subjects.

The Unit of Biomedical Ethics, Research Committee at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah approved the study protocol, which was conducted according to the principles of the Helsinki Declaration.

Study procedures

Prior to initiating data collection, workshops were conducted to train research assistants who would carry out the interview and data collection from participants. Two separate teams (a male team and a female team) were trained in administering the study questionnaire and obtaining the measurements described below.

The 2 trained teams of interviewers visited the schools on a daily basis. All Saudi employees aged ≥30 but ≤60 years at the selected schools, and who agreed to participate in the study were recruited. The trained interviewers organized and conducted research gathering points for the following purposes: 1. Obtain a signed approval of participation using a written informed consent from each subject. 2. Conduct interviews to obtain information needed to complete the Wisconsin Sleep Questionnaire2 in addition to information concerning demographics, excessive day sleepiness (EDS), sleep disorders symptoms, medical history, comorbidities, smoking status, dietary habits, social class, and consanguinity (defined as a possible marriage between first-degree cousins). 3. Obtain anthropometric measurements including height (H), weight (W), body mass index (BMI), neck circumference (NC), triceps skin fold thickness (TSF), waist/hip ratio (WHR), and the percent predicted neck circumference (PPNC) using the formula: PPNC = (1000 x NC)/([0.55 x H] + 310).15 Blood pressure measurement was taken using a digital sphygmomanometer (OMRON®, Osaka, Osaka Prefecture, Japan) following the standard method. Data from the 6 survey questions16 were answered using a 5-point frequency scale developed to categorize subjects as habitual snorers (HS), moderate snorers (MS), or non-snorers (NS). A score of 0 indicates never, a score of one indicates a frequency <1 episode per week, a score of 2 indicates a frequency of 1-2 episodes per week, a score of 3 indicates a frequency of 3-4 episodes per week, and a score of 4 indicates a frequency >4 episodes per week. Accordingly, the following definitions were utilized:16 the case was scored as regular or habitual snorer (HS) if he/she scored ≥3 for any of the 6 questions; the case was scored as MS if he/she scored 2 for any of the 6 questions; and the case was scored as NS if he/she scored 0 or one for any of the 6 questions. Excessive daytime sleepiness (EDS) was assessed using the Epworth sleepiness scale (ESS). The ESS is a validated self-administered questionnaire used for assessing levels of daytime sleepiness.17 The score for a normal individual is set to be at <10 score.17

A pilot study was performed; the 2 teams visited a single school and interviewed 21 subjects. Data from the pilot study were not included in the analysis. Pretesting of the questionnaire in the field during the pilot study was further focused on items that are difficult and confusing. Furthermore, ambiguous questions were rephrased to improve reliability. Intra-observer and inter-observer reliability were performed after extensive training and workshops that took us one month and held for the purpose of lowering the degree of unreliability between interviewers.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows version 22.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive statistics were expressed as the mean ± standard deviation (SD) for continuous variables and frequencies with percentages for categorical variables. The chi-square (X2) test was used for comparing between categorical variables, and one-way ANOVA for comparing between means of the 3 levels of HS. A logistic regression analysis was used to determine the predictors of snoring, with a binary outcome of snoring versus non-snoring. The odds ratio (OR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated. A 2-sided test with p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. Variables showing association with a p<0.1 in the bivariate analysis were included in the multivariate analysis as potential risk factors. Forward stepwise multiple logistic regression analysis was used to identify independent risk factors predictive of snoring.

Results

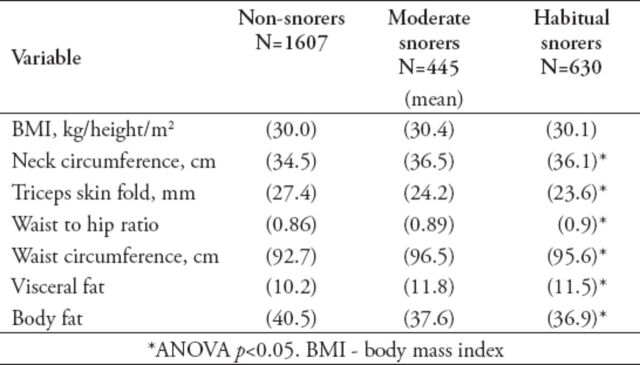

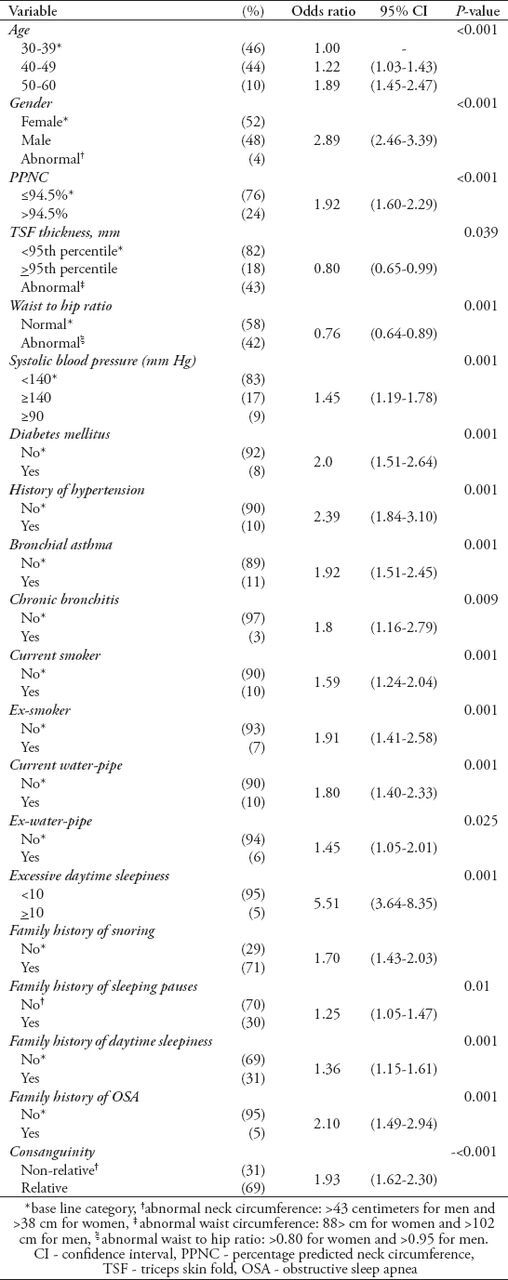

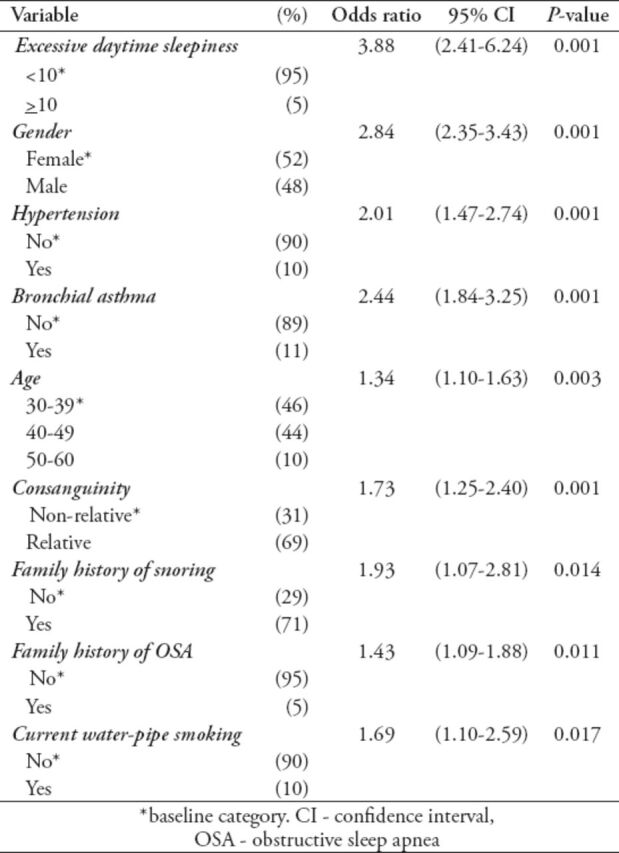

A total of 2682 cases (52.1% females, n=1397) were successfully interviewed giving a participation rate of 80.5 % (Table 1), and 40% were classified as snorers. The prevalence of HS was 23.5% (n=630), MS 16.6% (n=445), and NS 59.9% (n=1607) (Figure 1). Our results showed that 53% of males and 28% of females were snorers (p<0.01). The frequency of snoring significantly increased with age (p<0.01). The EDS based on ESS was found to be significantly higher among HS in the entire study population and in both genders (Table 1). There was no significant association between BMI and snoring. However, the mean BMI of the study population was 30.13 kg/m2, with 46% of participants having a BMI ≥30 kg/m2, such high prevalence of obesity did not give the variation in obesity variables to be tested (Table 2). A bivariate analysis showed that ageing (treated as a categorical variable), male gender, PPNC, as a relative measurement of neck circumference, waist to hip ratio, triceps skin fold thickness, diabetes mellitus, hypertension, asthma, chronic bronchitis, EDS, history of smoking, consanguinity, family history of snoring or OSA, and family history of EDS were all risk factors for snoring (Table 3). However, the multivariate analysis showed that none of the obesity or the body measurement parameters were significantly associated with being a snorer. Furthermore, only hypertension, asthma, EDS, water-pipe smoking, family history of snoring, or OSA, and consanguinity, in addition to male gender and ageing (as a linear variable), remained significant predictive risk factors in the multiple logistic regression analysis (Table 4).

Table 1.

Distribution of habitual snoring status with selected risk factors of subjects included in this study.

Figure 1.

Distribution of study population based on snoring habits among subjects included in this study.

Table 2.

Obesity parameters in habitual, moderate, and non-snorers subjects included in this study.

Table 3.

Bivariate logistic regression analysis for habitual snoring status (snorers [n=1075] versus non-snorers [n=1607]) with risk factors.

Table 4.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis of habitual snoring status (snorers [n=1075] versus non snorers [n=1607]) with risk factors.

Discussion

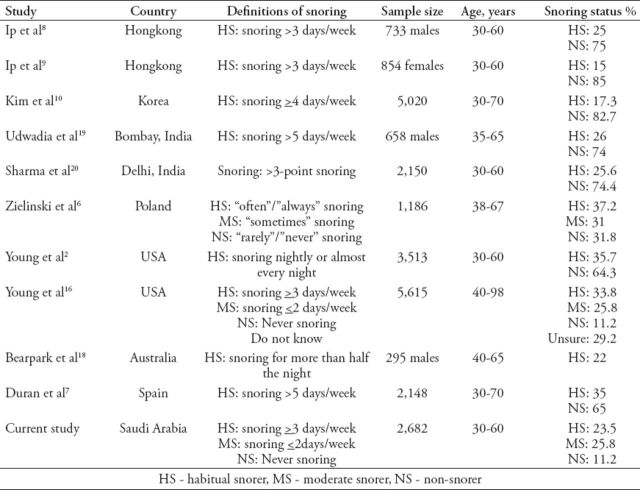

Our study showed that snoring is a common problem in Saudi Arabia, with 40% of the Saudi population sampled being snorers, of which 57.5% are HS. Furthermore, habitual snoring was more prevalent among Saudi males than females (31.4% versus 16.2%) (p<0.01). In our large sample size study (n=2682), the prevalence of HS among the Saudi population was 23.5%. A previous but limited sample size study focusing on health care workers in Saudi Arabia revealed that only 5.4% were HS,11 while another study used the Berlin questionnaire for sleep apnea that surveyed middle-aged Saudi patients comprised of 578 males and 400 females attending primary care clinics, found a much higher snoring prevalence of 52.3% among males and 40.8% among females.12,13 This difference in prevalence rate of snoring is due to variations in snoring definition, age range, sample size, severity level, and characteristics of the populations studied. Additionally, our finding regarding the prevalence of HS of 23.5% agrees with findings from other epidemiological studies that surveyed representative samples of the American,2,16 Australian,18 Polish,6 Spanish,7 Chinese,8,9 Korean,10 and Indian populations.19,20 Those studies found that the prevalence of HS ranged from 17-35% (Table 5).

Table 5.

Summary of the prevalence rates of snoring reported internationally by similar epidemiological studies.

Consistent with other studies,6,21,22 we found snoring to be twice as prevalent among males (31.4%) compared with females (16.2%) with p<0.01. A simple logistic regression analysis of snoring status with gender showed that males were 3-fold more likely to snore compared with females (OR: 2.89; 95% CI: 2.46-3.39; p=0.001). Additionally, ageing was also associated with an increased probability of snoring especially among individuals aged 50-60 years of age (OR: 1.89; 95% CI: 1.45-2.46; p=0.001). A recent systematic review of the literature identified a consistent male predominance among snorers in the general population.23 However, a multiple meta-regression analysis23 showed that ageing was the prominent effect modifier for the relationship between snoring and gender. The male predominance among snorers can probably be explained by gender differences in the upper airway anatomy and difference in hormonal affects. The later factor vanishes in postmenopausal women, and hence gender differences in snoring behavior decline in the elderly.

Our study examined various behavioral risk factors that might influence snoring. The bivariate analysis showed that being either a current, or a former smoker was a risk factor for snoring. However, only water-pipe smoking remained as an independent predictor for snoring in the logistic regression multivariate analysis (OR: 1.68; 95% CI: 1.10-2.59; p=0.017). We speculate that water-pipe smoking requires a more negative intra-pharyngeal pressure, which over the long-term, might lead to increased redundancy of the pharyngeal muscles. In general, our findings support previous evidence that smoking is a risk factor for snoring.6,8,16,18-20 This information is particularly valuable in the Saudi community where smoking is common; given that previous survey showed that almost one-third (27.9%) of Saudi adults are current or past smokers.24 A theory supporting the biological plausibility for a causal association between smoking and snoring revealed that smoking leads to chronic upper airway inflammation and irritation, which induce edema of pharyngeal mucosa with subsequent upper airway narrowing; setting on the snoring process.25 Excessive daytime sleepiness was found as an independent predictive factor for snoring (OR: 3.86; 95% CI: 2.40-6.24; p=0.00) (Table 4), which is in agreement with findings in previous studies.6,7,18,20 Significantly higher rates of EDS were also found among HS compared to NS and MS (p<0.05). This is probably explained by a higher prevalence in sleep apnea in this group of subjects,1 namely, both snoring and EDS commonly coexist as cardinal signs of OSA. On the contrary, obesity, and body measurements failed to show a significant association with snoring. This is probably because obesity is a very common disorder affecting both snorers and non-snorers in the Saudi population.26 In the current study, the mean BMI of the study population was 30.13 kg/m2, and 46% of participants had a BMI ≥30 kg/m2 that is to say the variation was minimal in BMI at the level of obesity and above.

Interestingly, consanguinity defined as possible marriage between first-degree cousins was significantly associated with HS in our sample of Saudi population. This risk factor, which is a common practice in certain Saudi families had not been previously investigated. The significant association between this new potential risk factor and snoring was shown in the bivariate analysis (OR: 1.93; 95% CI: 1.62-2.30; p<0.001) that persisted in the multivariate analysis. The significant association between family histories of snoring and OSA with HS (OR: 1.931; 95% CI: 1.068-1.811; p<0.014) and (OR: 1.429; 95% CI: 1.086-1.879; p<0.011) reported in our study concur with the considerable impact of consanguinity (Table 4). This finding is further supported by results from a previous study conducted in Asia, which reported a family history of snoring as an independent risk factor for HS (OR: 2.2; 95% CI: 1.56-3.12).27 Although epidemiologic studies have suggested that snoring might be related to hypertension, ischemic heart disease, and stroke,28,29 these studies did not distinguish the effects of snoring from those of coexisting OSA. An observational polysomnographic study of 1415 individuals, found that those without evidence of OSA have similar blood pressure measurements among snorers and non-snorers, and thus no relationship between hypertension and snoring was reported.29 In a more recent large observational study, Yeboah et al30 reported that snoring was not associated with an increased risk of ischemic heart diseases and all causes of mortality. Nevertheless, results from another relatively recent study suggested that snoring was independently associated with carotid artery atherosclerosis.5 This may be due to direct vibratory damage to endothelial cells resulting from heavy snoring. Our study revealed that only hypertension and bronchial asthma remained as independent risk factors (Table 4). We speculate that hypertension may actually be related to coexisting OSA rather than snoring per se. The association between bronchial asthma and snoring was reported by a number of investigators.31-33 However, it is not clear whether asthma was independently linked to snoring, or whether this association was related to other underlying features. Teodorescu et al31 reported that among 244 asthmatics, 37% had HS. In the same study, independent predictors of HS in these asthmatics were BMI >25 kg/m2, administering of inhaled corticosteroid, nasal congestion, and history of gastro-esophageal reflux.31

One of the limitations of our study is that it evaluated school employees, which may not represent the Saudi population as a whole. Thus, we aimed to collect data from a sample within schools that incorporated teachers and administrators as well as porters and drivers to best reflect the population in terms of various levels of socio-demographics, levels of education, and to capture both genders equally. Our large sample size also supports generalizability of results among middle-aged adults, but statistics on the general population are not available for a direct comparison. Another limitation is that our cross-sectional design limits our ability to draw any causal inferences due to an inability to establish temporality.

In conclusion, our study reveals that HS is a common disorder within the Saudi population. Ageing, male gender, EDS, family history of snoring, family history of OSA, water-pipe smoking, hypertention, asthma, and consanguinity were found to be significant predictive risk factors for HS. Consanguinity was identified as a new independent predictive risk factor of snoring. It is not clear whether snoring by itself has long-term adverse effects on health; however, our results do suggest a strong association between snoring and hypertension. These results can be used to assess the size of the problem and increase awareness of this health disorder among health care professionals, so that sleep disordered breathing can be effectively screened for, diagnosed, and treated.

Acknowledgment

The authors gratefully acknowledge Dr. Abdulfattah Touman, Dr. Ayman Krayem, Dr. Ibrahim Zakaria and Dr. Adil Alsulami for their generous help with data collection and Ms. Walaa Abuzahra for editing the manuscript.

Footnotes

Ethical Consent

All manuscripts reporting the results of experimental investigations involving human subjects should include a statement confirming that informed consent was obtained from each subject or subject’s guardian, after receiving approval of the experimental protocol by a local human ethics committee, or institutional review board. When reporting experiments on animals, authors should indicate whether the institutional and national guide for the care and use of laboratory animals was followed.

References

- 1.Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Peppard PE, Nieto FJ, Hla KM. Burden of sleep apnea: rationale, design, and major findings of the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort study. WMJ. 2009;108:246–249. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Skatrud J, Weber S, Badr S. Occurrence of sleep disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med. 1993;328:1230–1235. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304293281704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lindberg E, Janson C, Gislason T, Svärdsudd K, Hetta J, Boman G. Snoring and hypertension: a 10 year follow-up. Eur Respir J. 1998;11:884–889. doi: 10.1183/09031936.98.11040884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dunai A, Keszei AP, Kopp MS, Shapiro CM, Mucsi I, Novak M. Cardiovascular disease and health-care utilization in snorers: a population survey. Sleep. 2008;31:411–416. doi: 10.1093/sleep/31.3.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee SA, Amis TC, Byth K, Larcos G, Kairaitis K, Robinson TD, et al. Heavy snoring as a cause of carotid artery atherosclerosis. Sleep. 2008;31:1207–1213. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zielinski Jl, Zgierska A, Polakowska M, Finn L, Kurjata P, Kupsc W, et al. Snoring and excessive daytime somnolence among Polish middle-aged adults. Eur Respir J. 1999;14:946–950. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3003.1999.14d36.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duran J, Esnaola S, Rubio R, Iztueta A. Obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea and related clinical features in a population-based sample of subjects aged 30 to 70 yr. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:685–689. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.3.2005065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ip MS, Lam B, Lauder IJ, Tsang K, Chung K, Mok Y, et al. A community study of sleep disordered breathing in middle-aged Chinese men in Hong Kong. Chest. 2001;119:62–69. doi: 10.1378/chest.119.1.62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ip MS, Lam B, Tang LC, Lauder IJ, Ip TY, Lam WK. A community study of sleep-disordered breathing in middle-aged Chinese women in Hong Kong: prevalence and gender differences. Chest. 2004;125:127–134. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.1.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kim J, In K, Kim J, You S, Kang K, Shim J, et al. Prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing in middle-aged Korean men and women. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;170:1108–1113. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200404-519OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wali SO, Krayem AB, Samman YS, Mirdad S, Alshimemeri AA, Almobaireek A. Sleep Disorders in Saudi Health Care Workers. Ann Saudi Med. 1999;19:406–409. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.1999.406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.BaHammam AS, Alrajeh MS, Al Jahdali HH, BinSaeed AA. Prevalence of symptoms and risk of sleep apnea in middle-aged Saudi males in primary care. Saudi Med J. 2008;29:423–426. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bahammam AS, Al Rajeh MS, Al Ibrahim FS, Arafah MA, Sharif MM. Prevalence of symptoms and risk of sleep apnea in middle-aged Saudi women in primary care. Saudi Med J. 2009;30:1572–1576. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang W. Clinical Epidemiology Basic Principles and Practical Applications. Beijing (China): Higher Education Press; 2012. pp. 884–889. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mitler MM, Miller JC. Methods of testing for sleepiness [corrected] Behav Med. 1996;21:171–183. doi: 10.1080/08964289.1996.9933755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Young T, Shahar E, Nieto FJ, Redline S, Newman AB, Gottlieb DJ, et al. Predictors of sleep-disordered breathing in community-dwelling adults: the Sleep Heart Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:893–900. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.8.893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: the Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14:540–545. doi: 10.1093/sleep/14.6.540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bearpark H, Elliott L, Grunstein R, Cullen S, Schneider H, Althaus W, et al. Snoring and sleep apnea. A population study in Australian men. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1995;151:1459–1465. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.151.5.7735600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Udwadia ZF, Doshi AV, Lonkar SG, Singh CI. Prevalence of sleep-disordered breathing and sleep apnea in middle-aged urban Indian men. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2004;169:168–173. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200302-265OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sharma SK, Kumpawat S, Banga A, Goel A. Prevalence and risk factors of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome in a population of Delhi, India. Chest. 2006;130:149–156. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.1.149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jennum P, Sjol A. Snoring, sleep apnoea and cardiovascular risk factors: the MONICA II Study. Int J Epidemiol. 1993;22:439–444. doi: 10.1093/ije/22.3.439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ohayon MM, Guilleminault C, Priest RG, Caulet M. Snoring and breathing pauses during sleep: telephone interview survey of a United Kingdom population sample. BMJ. 1997;314:860–863. doi: 10.1136/bmj.314.7084.860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chan CH, Wong BM, Tang JL, Ng DK. Gender difference in snoring and how it changes with age: systematic review and meta-regression. Sleep Breath. 2012;16:977–986. doi: 10.1007/s11325-011-0596-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Khattab A, Javaid A, Iraqi G, Alzaabi A, Ben Kheder A, Konsiki ML, et al. Smoking habits in the Middle East and North Africa: results of the BREATHE study. Respir Med. 2012;106:S16–S24. doi: 10.1016/S0954-6111(12)70011-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bowen-Davis A. Pharyngitis-acute and chronic. In: Ballantyne J, Groven J, editors. Disease of the ear, nose, and throat. London (UK): Butterworths; 1971. p. 75. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Al Othaimeen AI, Al Nozha M, Osman AK. Obesity: an emerging problem in Saudi Arabia: analysis of data from the National Nutrition Survey. East Mediterr Health J. 2007;13:441–448. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Khoo SM, Tan WC, Ng TP, Ho CH. Risk factors associated with habitual snoring and sleep-disordered breathing in a multi-ethnic Asian population: a population-based study. Respir Med. 2004;98:557–566. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2003.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Koskenvuo M, Kaprio J, Telakivi T, Partinen M, Heikkila K, Sarna S. Snoring as a risk factor for ischeamic heart disease and stroke in men. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1987;294:16–19. doi: 10.1136/bmj.294.6563.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoffstein V. Blood pressure, snoring, obesity, and nocturnal hypoxaemia. Lancet. 1994;344:643–645. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(94)92084-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yeboah J, Redline S, Johnson C, Tracy R, Ouyang P, Blumenthal RS, et al. Association between sleep apnea, snoring, incident cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality in an adult population: MESA. Atherosclerosis. 2011;219:963–968. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Teodorescu M, Consens FB, Bria WF, Coffey MJ, McMorris MS, Weatherwax KJ, et al. Predictors of habitual snoring and obstructive sleep apnea risk in patients with asthma. Chest. 2009;135:1125–1132. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-1273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Knuiman M, James A, Divitini M, Bartholomew H. Longitudinal study of risk factors for habitual snoring in a general adult population: the Busselton Health Study. Chest. 2006;130:1779–1783. doi: 10.1378/chest.130.6.1779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Alharbi M, Almutairi A, Alotaibi D, Alotaibi A, Shaikh S, Bahammam AS. The prevalence of asthma in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Prim Care Respir J. 2009;18:328–330. doi: 10.4104/pcrj.2009.00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]