Abstract

Objective

This study examined a school- and home-based mental health service model, Links to Learning (L2L), focused on empirical predictors of learning as primary goals for services in high poverty urban communities.

Method

Teacher key opinion leaders (KOLs) were identified through sociometric surveys and trained, with mental health providers (MHPs) and parent advocates (PAs), on evidence-based practices to enhance children’s learning. KOLs and MHPs co-facilitated professional development sessions for classroom teachers to disseminate two universal (Good Behavior Game, Peer Assisted Learning) and two targeted (Good News Notes, Daily Report Card) interventions. Group-based and home-based family education and support were delivered by MHPs and PAs for K-4th grade children diagnosed with one or more disruptive behavior disorder. Services were Medicaid-funded through four social service agencies (N = 17 providers) in seven schools (N = 136 teachers, 171 children) in a two (L2L vs. services-as-usual SAU]) by six (pre- and post-tests for three years) longitudinal design with random assignment of schools to conditions. SAU consisted of supported referral to a nearby social service agency.

Results

Mixed effects regression models indicated significant positive effects of L2L on mental health service use, classroom observations of academic engagement, teacher report of academic competence and social skills, and parent report of social skills. Nonsignificant between-group effects were found on teacher and parent report of problem behaviors, daily hassles, and curriculum based measures. Effects were strongest for young children, girls, and children with fewer symptoms.

Conclusions

Community mental health services targeting empirical predictors of learning can improve school and home behavior for children living in high poverty urban communities.

Keywords: School-based mental health, disruptive behavior disorder, urban communities, key opinion leaders, public health

Improving the accessibility and effectiveness of community mental health services for children has been a national concern for more than a decade (National Advisory Mental Health Council, 2001). In a seminal study, secondary data analysis of three nationally representative household surveys indicated that nearly 80% of low-income youth in need of mental health services did not receive services in the preceding 12 months, with rates approaching 90% for uninsured families (Kataoka, Zhang, & Wells, 2002). Lack of access to services is especially problematic in urban, low-income communities with high rates of nonattendance at initial appointments and rates below 10% for attendance at as few as four sessions (see McKay & Bannon, 2004). Infrequent use of mental health services has been attributed to stigma (Dempster, Wildman, & Keating, 2013) and concrete obstacles, such as inaccessible locations, lack of information about services, and social isolation (Harrison, McKay, & Bannon, 2004). Concentrated urban poverty also is associated with high risk of substantial mental health difficulties for youth (Cappella, Frazier, Atkins, Schoenwald, & Glisson, 2008). A longitudinal analysis of a large nationally representative sample of youth indicated a robust relation between neighborhood disadvantage and conduct problems over and above a series of family and individual risk factors (Goodnight, et al., 2012). Relatedly, exposure to community violence, affecting almost 80% of urban children (U.S. Department of Justice, 2003), is associated with poor academic performance (McCoy, Roy, & Sirkman, 2013) mediated by depression and disruptive behavior (Borofsky, Kellerman, Baucom, Oliver, & Margolin, 2013).

A public health framework offers promise for organizing the design and delivery of more accessible and appropriately targeted services to children living in urban poverty. Within a public health framework, universal intervention strategies are deployed to attenuate risk factors and related behavior problems, while targeted interventions are simultaneously deployed for high-risk cases (Stiffman, Stelk, Evans, & Atkins, 2010). If delivered in those contexts naturally inhabited by children and families – primarily school and home – and focused on specific aspects of those contexts affecting child learning and behavior, service models encompassing such interventions also could be more effective and sustainable (Atkins & Frazier, 2011). In this study, we examined a service delivery model, Links to Learning (L2L), which involved the integration and delivery of universal and targeted interventions focused on supporting schooling for children with disruptive behavior disorders living in urban low-income communities.

School-Based Mental Health Services

Schools are the de facto providers of mental health services for children and youth (Farmer, Burns, Phillips, Angold, & Costello 2003; Green et al., 2013), providing an estimated 70% to 80% of psychosocial services (Rones & Hoagwood, 2000). However, the primary modality for school-based services, individual counseling (Foster et al., 2005), is largely ineffective for children with disruptive behavior disorders, which comprise the majority of school referrals (Farmer, Compton, Burns, & Robertson, 2002; Foster et al., 2005). This is especially evident for children attending schools in low-income urban communities. In a recent meta-analysis examining school-based mental health programs for low-income, urban youth (Farahmand, Grant, Polo, Duffy, & DuBois, 2011), null effects were found for most outcomes (mean ES = .08), and negative effects were found for programs focused on externalizing behaviors (ES = −.11). The authors suggested that these findings reflect a lack of attention to the many stressors apparent in low-income urban schools and proposed that effective services would require an integration of the school ecology into program planning and implementation.

A second meta-analysis of programs based in community mental health settings serving low income urban youth (Farahmand et al., 2012) found positive effects for programs that supported parents or provided other community supports (mean ES = .38), and null effects for programs focused on direct services to youth (mean ES = .03). These findings suggest that individually focused services are contraindicated for low-income youth with disruptive behavior and that interventions are likely to be more impactful when they can be deployed in, and alter, family and community contexts. In the present study, we implemented and examined a model in which community mental health staff worked directly with parents and teachers in low-income urban schools to enhance children’s school success.

Predictors of Children’s Learning: Teachers and Parents

Informed by evidence supporting the effectiveness of focusing mental health services on the empirical predictors of youth offending (Henggeler, Schoenwald, Borduin, Rowland, & Cunningham, 1998), we constructed a model focusing mental health services on the empirical predictors of children’s learning to impact children’s school success (see Cappella et al., 2008). An extensive literature documents that children’s academic learning is compromised in urban low-income schools, with profound and growing gaps between poor and nonpoor U.S. children (Reardon, 2011). This has important implications given that academic achievement is a hallmark of children’s sense of competence (Masten & Curtis, 2000), and critical to social and emotional adjustment (Roeser, Eccles, & Freedman-Doan, 1999). Academic achievement can operate as a protective factor for urban children (Freudenberg & Ruglis, 2007), and is associated with positive relationships with peers, teachers, and parents, and improved classroom behavior (Atkins, Hoagwood, Kutash, & Seidman, 2010). In addition, a direct focus on schooling by mental health providers could bridge educational and mental health systems, and provide additional resources to struggling urban schools (Ringeisen, Henderson, & Hoagwood, 2003).

Reviews of the educational literature reveal that teachers and parents contribute uniquely to children’s learning. Specifically, three components of teacher practices most significantly impact children’s learning: Effective instruction, classroom management, and teacher outreach to parents (Stringfield, 1994). Similarly, parent communication with teachers, homework support, and reading at home are associated with improved learning (Jeynes, 2005). These classroom and family predictors of learning were the focus of the mental health service model developed for this study (Cappella et al., 2008).

Diffusion of Innovation: Teacher Key Opinion Leaders and Parent Advocates

Diffusion theory posits that key opinion leaders (KOLs) spread innovations as a function of their influential role within their social network (Rogers, 1995). In the first study applying diffusion theory to urban schools (Atkins et al., 2008), KOL teachers, working with mental health providers (MHPs), promoted higher rates of teachers’ self-reported use of recommended interventions than consultation from MHPs without KOL support. These results supported an expanded role for KOL teachers for the dissemination of school-based mental health interventions. Similarly, involving parents with similar characteristics and experiences as the parents of children referred for services can reduce stigma, enhance participation in services, and influence behavior change due to shared experiences and reduced social distance (Frazier, Abdul-Adil, Atkins, Gathright, & Jackson, 2007; Hoagwood et al., 2010).

The Current Study

We examined the extent to which a mental health model, Links to Learning (L2L), focused on the key predictors of student learning and delivered by community mental health providers aligned with parent advocates and KOL teachers, would lead to greater reductions in children’s disruptive behavior at home and school as compared to mental health services-as-usual (SAU). Moderators included baseline child and family characteristics. This three-year longitudinal study utilized a multi-method, multi-informant design consisting of classroom observations, teacher report, parent report, and direct assessment of academic performance with random assignment of schools to L2L or assisted referral to community based SAU.

Method

Setting

This study was conducted in collaboration with four community mental health agencies and seven public elementary schools in a large midwestern city. University and school district IRB approvals were obtained prior to initiating study procedures.

Mental health agencies serving low-income African American children and families received written invitations to participate in the study. The first four agencies contacted agreed to participate and two of the four agencies were large enough to have independent providers assigned to each study condition. The remaining two agencies provided services in either the L2L or SAU condition. In both conditions, providers billed through a fee-for-service model reimbursable by Medicaid. Agencies in each condition reserved intake times for initial appointments for families who consented to participate in the study.

Following the identification of participating agencies, elementary schools (N = 325) were screened on the following criteria to prioritize schools with greatest need and maximize comparability within and across conditions: (a) 85% or greater low income, (b) 85% or greater African American students, (c) average reading scores on statewide testing below the 35th percentile (M = 27.9, SD = 3.8), and (d) school population within one standard deviation of the district mean (M = 702, SD = 306). Identified schools (n = 58) were further categorized by location within a three mile radius of participating mental health agencies to facilitate collaboration and minimize distance as a possible barrier to service use. From this list, six schools of similar size and proximity were randomly selected, three for each condition. Based on school district records, participating schools were characterized as 98% low income and 97% African American. No schools had preexisting relationships with participating agencies. One school withdrew from the L2L condition when the principal retired after the first year of the study. A replacement school was randomly selected from the original set of schools within three miles of the mental health agency consistent with initial procedures.

Sample and Recruiting Procedures

Children and families

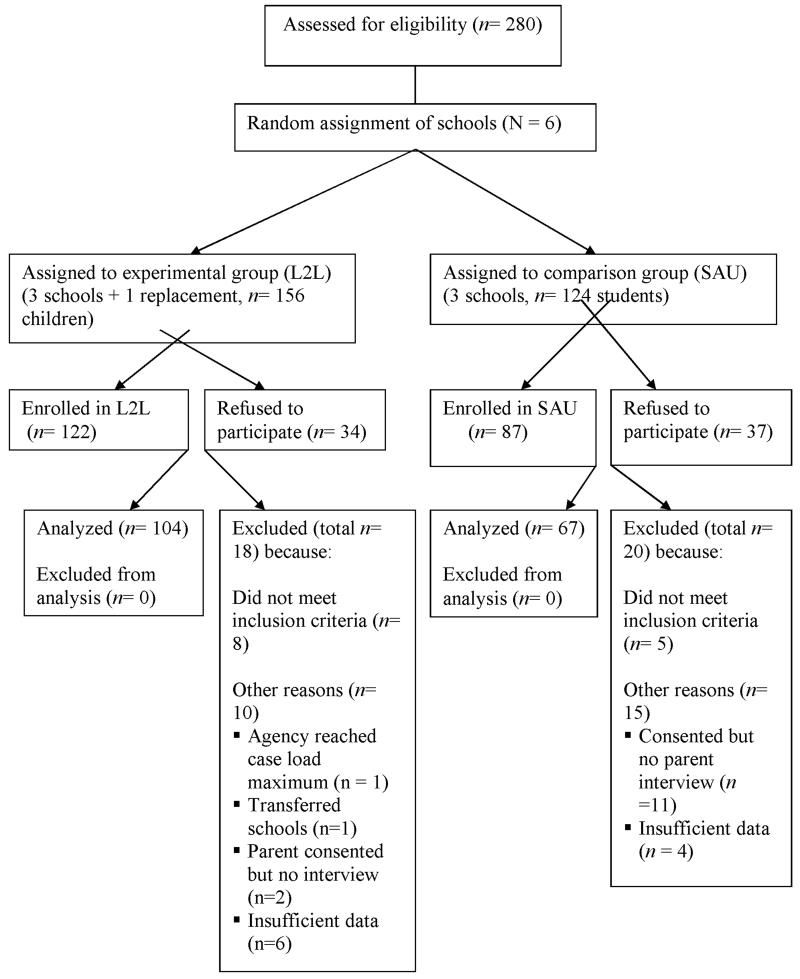

Table 1 presents demographic characteristics of participating children, parents, and teachers. As indicated in Figure 1, a total of 280 children and families enrolled in the study. Recruitment involved a three-step multiple-gating procedure to maintain the confidentiality of families and minimize burden to teachers. In the first step, consented teachers in grades K-4 completed the Systematic Screening for Behavior Disorders (SSBD; Walker & Severson, 1990) on up to ten students for whom they had concerns regarding externalizing behaviors. Second, teachers sent SSBD forms to their school behavioral health team to determine if a referral was appropriate and to initiate contact with eligible families about the research opportunity. These procedures protected the identity of families not interested in participating and more closely approximated the process schools use routinely to refer children to mental health agencies. Third, interested families were referred by the school behavioral health teams to the investigators and invited to consent.

Table 1. Sample Baseline Demographic Characteristics.

| Demographic Characteristics | Links to Learning | Services As Usual | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Child | (n = 104) | (n = 67) | (N = 171) | |

| Age in years, M (SD) | 7.42 (1.81) | 7.66 (1.53) | 7.51 (1.71) | |

| Gender | Boys | 74 (71%) | 50 (75%) | 124 (73%) |

| Girls | 30 (29%) | 17 (25%) | 47 (27%) | |

| African American | 98 (94%) | 62 (93%) | 160 (93.6%) | |

| Latino/a | 1 (1%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.6%) | |

| Multiracial | 2 (2%) | 4 (6%) | 6 (3.5%) | |

| Other | 3 (3%) | 1 (1%) | 4 (2.3%) | |

| DBD Diagnosis1 | ||||

| DBD Diagnosis1 | ADHD | 41 (39%) | 38 (57%) | 79 (46%) |

| ODD | 30 (29%) | 31 (46%) | 61 (36%) | |

| CD | 16 (15%) | 19 (28%) | 35 (20%) | |

| Parent | (n = 97) | (n = 61) | (N = 158) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, M (SD)2 | 32.06 (7.92) | 32.64 (8.44) | 32.28 (8.10) | |

| Gender3 | Male | 1 (1%) | 6 (10%) | 7 (4%) |

| Female | 94 (97%) | 55 (90%) | 149 (94%) | |

| Employment | Full-time | 27 (28%) | 15 (25%) | 42 (27%) |

| Part-time | 19 (20%) | 11 (18%) | 30 (19%) | |

| Unemployed | 39 (40%) | 28 (46%) | 67 (42%) | |

| Other | 12 (12%) | 7 (11%) | 19 (12%) | |

| Income | $0-$10,000 | 59 (61%) | 31 (50.8%) | 90 (57%) |

| $11,000-$20,000 | 19 (20%) | 11 (18.0%) | 30 (19%) | |

| $21,000-$30,000 | 9 (9%) | 12 (19.7%) | 21 (13%) | |

| $31,000-$40,000 | 2 (2%) | 1 (1.6%) | 3 (2%) | |

| Over $40,000 | 4 (4%) | 1 (1.6%) | 5 (3%) | |

| Declined to report | 4 (4%) | 5 (8.2%) | 9 (6%) | |

| Education | GED | 11 (11.3%) | 9 (15%) | 20 (12.7%) |

| High School | 46 (47.4%) | 28 (46%) | 74 (46.8%) | |

| Some College | 21 (21.6%) | 14 (23%) | 35 (22.2%) | |

| Bachelor’s Degree | 4 (4.1%) | 0 (0%) | 4 (2.5%) | |

| Other | 15 (15.5%) | 10 (16%) | 25 (15.8%) |

| Teachers4 | (n = 71) | (n = 65) | (N =136) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years, M (SD)5 | 41.44 (13.46) | 35.58 (11.46) | 38.37 (12.73) | |

| Gender6 | Male | 7 (10%) | 6 (9%) | 13 (10%) |

| Female | 52 (73%) | 51 (78%) | 103 (76%) | |

| Race/Ethnicity6 | Black | 37 (52%) | 30 (46%) | 67 (49%) |

| White | 21 (30%) | 21 (32%) | 42 (31%) | |

| Latino/a | 0 (0%) | 2 (3%) | 2 (1%) | |

| Asian American | 0 (0%) | 2 (3%) | 2 (1%) | |

| Other | 1 (1%) | 2 (3%) | 3 (2%) | |

| Yrs Teaching7 | Novice (0-3) | 12 (17%) | 26 (40%) | 38 (28%) |

| Mid Career (4-6) | 7 (10%) | 9 (14%) | 16 (12%) | |

| Experienced (7-37) | 39 (55%) | 22 (34%) | 61 (45%) |

Note.

ADHD collapsed across all subtypes, Ns do not reflect comorbidity.

Three parents in the L2L condition and three parents in the SAU condition did not report age.

Two parents in the treatment condition did not report gender.

KOLs are included in the sample of intervention teachers.

Twenty-one teachers in the L2L condition and ten teachers in the SAU condition did not report age.

Twelve teachers in the L2L condition and eight teachers in the SAU condition did not report race/ethnicity.

Thirteen teachers in the L2L condition and eight teachers in the SAU condition did not report teaching experience.

Figure 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram.

L2L = Links to Learning; SAU = Services as Usual.

Eligibility was determined by parent or teacher report on the DBD Rating Scale (Pelham, Gnagy, Greenslade, & Milich, 1992) for one or more disruptive behavior disorder. There were no differences across conditions in the proportion enrolled (χ2 < 1, p > .60), child or parent demographic variables, or child diagnostic characteristics (all ps > .05). Parents interested in mental health services for their child who declined participation were referred to a non-participating nearby community mental health agency.

Data collection was discontinued for 81 children who changed schools over the course of the study (n = 44 L2L; n = 37 SAU) and seven families (n = 5 L2L; n = 2 SAU) who withdrew from the study. Attrition rates did not differ across conditions (χ2 < 1, p > .40); 53% of L2L children (n = 55) and 31% of SAU children (n = 28) participated until the conclusion of the study (3 years, 6 time points). In the L2L condition, 28% of children (n = 29 of 104) enrolled during year 2; ongoing enrollment mirrored real world patient flow and helped maintain providers’ caseloads. In the SAU condition, enrollment was discontinued after year 1 at the school’s request, as it had become clear that participating families were not attending clinic-based services. The final sample included 104 children in the L2L condition and 57 children in the SAU condition, for whom data collection continued for the duration of the study (see Figure 1).

Teachers

A total of 136 teachers participated in the study (n = 71 L2L, n = 65 SAU). Consent rates were 89% for L2L and 93% for SAU teachers. There were no significant differences across condition on demographic variables with the exception that SAU teachers had fewer years of teaching experience (χ2 (1, N =136) = 10.906; p < .001). Teachers were predominantly female (89%) and African American (58%), with an average of 12 years of experience (SD = 12.04). Teacher attrition did not differ across conditions, (χ2 < 1, p > .38), with 69% of L2L teachers (n = 49) and 54% of SAU teachers (n = 35) participating for the duration of the study. Nineteen teachers did not contribute child data, resulting in an analytic sample of 117 teachers (L2L n = 60, SAU n = 57).

Experimental Condition: Links to Learning (L2L)

The L2L service model was delivered in classrooms and homes by a team consisting of a community mental health provider (MHP) and a parent advocate (PA) who billed Medicaid for direct contact with children, parents, and teachers. Teacher key opinion leaders (KOLs) facilitated uptake of classroom interventions recommended by the mental health team.

Key opinion leader teachers (KOLs)

KOLs (n = 10) were identified via sociometric interviews at each school with all instructional staff (n = 141, 94% interview participation) to yield a pair of eligible teachers who together were aligned via advice networks with the most K-4th grade teachers at that school. As described in prior studies (Neal, Neal, Atkins, Henry, & Frazier, 2011; Neal, Shernoff, Frazier, Stachowicz, Frangos, & Atkins, 2008), teachers nominated colleagues from whom they most often sought advice related to the predictors of learning (instruction, classroom management, and family outreach). Six teachers declined to participate as KOLs, citing workload concerns, although they did agree to participate in the study as classroom teachers. When one teacher declined, a new pair of teachers was identified who were connected to the most teachers at their school. All participating KOLs remained in this role throughout the study. KOLs were 90% female, 50% earned MA degrees, 50% earned BA degrees, with mean age of 43.14 (SD = 14.41), and mean years of experience of 23.8 (SD = 11).

Agency teams

Community mental health teams consisted of licensed MHPs paired with PAs employed by the agency. Seventeen providers consented to participate (n = 11 MHPs and n = 6 PAs). Providers were predominantly female (n = 8 MHPs and n = 5 PAs) and had been in practice on average 5.7 years (SD = 3.96; range: 2 – 16 years). Three MHPs had MSW degrees, five had BAs, and one had an AA degree. Two PAs had a BA degree, and the remaining four had high school diplomas. Information on race was available for all PAs (n = 6 African American) and 10 of 11 MHPs (n = 5 African American; n = 4 European American; n = 1 multiracial). The mean age of MHPs was 32.5 years (SD = 8.73). Six providers withdrew from the study, four when their employment with the agency ended and two citing workload concerns.

Classroom intervention

Two universal (Good Behavior Game and Peer Assisted Learning) and two targeted interventions (Daily Report Card and Good News Notes) were selected based on empirical evidence of their impact on key predictors of learning and endorsement by KOL teachers. Implementation was facilitated by MHPs and PAs via case-centered consultation through conjoint parent-teacher meetings (Sheridan & Kratochwill, 2007).

Good Behavior Game (GBG) is a widely used contingency-based behavior management program. During designated instructional activities, teams of students receive praise for rule following and lose points for rule violations toward daily or weekly rewards for good behavior (Barrish, Saunders, & Wolf, 1969). GBG has been widely studied with strong evidence for improved classroom behavior and academic performance (Flower, McKenna, Bunuan, Muething, & Vega, 2014).

Peer Assisted Learning Strategies (PALS) is a student-paired reading intervention. Stronger readers (tutors) are paired with less skilled readers (tutees), and together they follow systematic steps for reading practice with feedback (Fuchs, Fuchs, & Burish, 2000). Reading materials correspond to the tutee’s instructional level, and include pre-literacy tools such as flashcards, as needed. A meta-analytic review indicated positive effects on achievement, especially for elementary age low-income urban children (Rohrback, Ginsberg-Block, Fantuzzo, & Miller, 2003).

The Daily Report Card (DRC) is a targeted intervention in which teachers and parents jointly identify, monitor, and reinforce three to five individualized behaviors that interfere with learning (Kelley & McCain, 1995). Teachers and parents select a rating system to track behaviors, a reward schedule, and a plan for monitoring intervals. Direct feedback to students and communication from school to home has been shown to lead to improvements in behavior and academic performance (Vannest, Davis, Davis, Mason, & Burke, 2010).

Good News Notes (GNN) are certificates sent home by teachers about desired behaviors (e.g., rule following, work completion) to provide positive weekly feedback to parents (Lahey et al., 1977). GNN are widely recommended to identify student strengths, scaffold behavior improvement by reinforcing small achievements, and balance infraction reports with positive feedback to families (e.g., Epstein, Atkins, Cullinan, Kutash, & Weaver, 2008).

Family intervention

The family intervention was manualized and derived from the empirical literature on parental support of academic learning (Sheridan & Kratochwill, 2007). The intervention was group-delivered weekly at each school for 8 weeks by MHPs and PAs or individually via home visits for parents unable to attend groups. The intervention targeted home-school communication, home routines that support learning, homework support, and daily reading (Patall, Cooper & Robinson, 2008; Serpell, Sonnenschein, Baker, & Gannapathy, 2002). Individualized case management services also were provided as needed.

Training and supervision

KOLs earned university graduate credit for participating in a web-based course, designed and taught by the research team, to learn the classroom and family interventions. MHPs also participated in the web-based course, which was asynchronous to facilitate participation at times convenient for KOLs and MHPs. MHPs also attended separate trainings with PAs on the family intervention (two days) and case consultation (two days). Weekly two-hour supervision sessions, co-led by agency supervisors and university consultants for MHP-PA teams, focused on reviewing student progress, problem-solving barriers to intervention implementation, and facilitating fidelity to the interventions (Schoenwald, Mehta, Frazier, & Shernoff, 2013). Supervision sessions and field-based training were used to train new agency providers and also served as booster training for existing teams. All ten KOLs and nine of eleven MHPs successfully completed the web-based course; seven MHPs and four PAs completed the additional four days of training on family intervention and case consultation. Agency supervision was provided weekly for MHPs and PAs. Agency supervisors attended 90% of supervision sessions, MHPs attended 72%, and PAs attended 43%.

Dissemination of the classroom intervention

KOLs hosted weekly meetings to introduce and endorse the universal and targeted interventions presented in the web-based course. The meetings were approved by the school district and each school’s principal for professional development credit and offered during the spring of the first year of participation, before and after school hours, with MHPs attending in a supportive role. Meetings lasted 1 hour weekly for three months in three schools, and 2 hours weekly for one month in one school. KOLs were paid $250 per semester and teachers received $100 for participating in eight or more. Meetings were followed by classroom demonstrations of universal and targeted interventions by KOLs and university consultants, supported by MHPs and PAs. For teachers new to the school or in need of additional support, booster training was provided by KOLs and MHPs with support of university consultants. Meetings were well attended by classroom teachers (n = 51), with 78% attending at least one and 63% (n = 32) attending more than 50% (range = 0.63 to 1.00, M = 0.83, SD = 0.13). Teachers who enrolled in L2L after the meetings had concluded (n = 20) were introduced to the recommended interventions through individual meetings with KOLs.

Comparison Condition: Services as Usual (SAU)

Families were referred to a participating community mental health agency for mental health services by licensed providers with no restrictions on type or frequency of services.

Measures

Fidelity Monitoring

Fidelity measures were developed to examine adherence to core components of the service model. Parents were administered a 31-item checklist twice annually assessing the frequency and quality of support received on homework routines, home-school communication, and reading. Agency staff completed an 18-item checklist monthly on the structure and content of supervision. Teachers completed two scales monthly: a 31-item checklist assessing frequency and quality of support from KOLs and mental health teams, and a calendar to record use of recommended interventions. Information on scale development and psychometric properties of fidelity measures is described separately (Schoenwald et al., 2013).

Fidelity of classroom-based implementation

Fidelity checklists of KOL classroom support were completed by 75% of teachers (n = 53; n = 128 checklists submitted). Surveys indicated that 83% (n = 44) reported that a KOL teacher visited their classroom at least a few times and 68% (n = 36) reported many times. Meetings took place outside of class time a few times for 81% (n = 43, and many times for 45% (n = 24). KOLs offered general support at least a few times for 89% (n = 47) and many times for 77% (n = 41). Monthly fidelity calendars were submitted by 83% of teachers (n = 59). Calendars revealed that teachers used recommended interventions at a high rate, with more frequent use of universal strategies (Good Behavior Game: 80%; Peer Assisted Learning: 76%) than targeted strategies (Daily Report Card: 56%; Good News Notes: 53%).

Fidelity of home-based implementation

One or more fidelity checklist was submitted by 60% of parents (n = 62) over the course of the study, to provide an assessment of home support received from the mental health agency team. Of those parents who completed surveys, 82% (n = 51) reported that they spoke with their MHP or PA by phone or at school at least a few times, 47% parents (n = 29) reported many times. Forty percent of parents (n = 25) reported receiving a home visit at least a few times, 18% parents (n = 11) reported many times.

Service Use

Based on review of agency records in each condition, service use was computed as the average number of outpatient service minutes per day per time point billed to Medicaid. These included direct services to children, parents, and teachers (billed as collateral consults). Distribution of services across billing codes is available upon request.

Child Behavior at Home and School

Behavioral Observation of Students in Schools (BOSS; Shapiro, 2004) is a classroom observation system that includes three off task behaviors (motor, verbal, passive) averaged to form a total off task score (BOSS Off Task), and two engagement behaviors (active, passive) summed to form a total engagement score (BOSS Engagement). As per standardized procedures, two 15-minute observations of target students (sixty 15-second intervals) were conducted on consecutive days twice annually to generate: (1) scores of target students based on forty-eight observations; and (2) scores of randomly selected peers (Peer Comparisons, PC), in the same classroom as the target student and matched for gender, based on twelve observations for comparisons of target students data of normative peers within their classroom. Observers chose the PC by rotating to a different peer every fifth interval, therefore observing twelve peers in a given observation and twenty-four peers across the two observations per classroom per time point. Observers were blind to condition and trained to a minimum of 80% inter-observer agreement. BOSS observations were discontinued in SAU schools after the first year because teachers expressed dissatisfaction with the amount of time observers were spending in their classrooms. Observations were continued in L2L schools as no such concerns were expressed.

Social Skills Rating System (SSRS; Gresham & Elliott, 1990) was completed by parents and teachers to assess social skills (46 items), problem behaviors (33 parent, 30 teacher items), and academic competence (teachers only, 10 items) on a 3-point scale. Year 1 baseline internal reliability was high for Social Skills (α = .85 teachers, α = .87 parents), Problem Behaviors (α = .86 teachers, α = .86 parents), and Academic Competence (α = .93). Social Skills and Problem Behaviors were examined as outcome variables and Academic Competence was a moderator.

Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ; Goodman, 2001) consists of 25 items completed by teachers and parents on 5 subscales related to children’s behavioral problems and prosocial behavior. Impact scores, examined as moderators, assessed overall distress and social impairment ranging from 0-10 (parent report) and 0-6 (teacher report) (Goodman, 2001). Year 1 baseline internal reliability for the impact score was α = .76 (parent) and α = .56 (teacher).

Hassles and Uplifts Scale (DeLongis, Folkman, & Lazarus, 1988) assesses parent perceptions of daily events on a 4-point scale. Data on hassles were analyzed as a continuous variable and moderator on baseline items. Baseline internal reliability was high (α = .94).

Academic Performance

Curriculum-based measures (CBM; Shapiro, 2004) are standardized reading probes (see www.aimsweb.com) individually administered in fall, winter, and spring of each school year designed to reflect a student’s oral reading growth. A reading ability score (number of words read correctly per minute) was computed to yield a percentage correct score. Observers were trained on standardized master-coded DVDs to a criterion of 80% agreement. Reliability was assessed yearly on 15% of administrations to 80% criterion.

Academic Competence Evaluation Scales (ACES; DiPerna & Elliot, 1999) is a multidimensional measure of children’s academic competence. Teachers completed the 30 items rated on a 5-point scale (1 = Never to 5 = Almost Always) measuring perceptions of student engagement, motivation, and study skills. Baseline internal reliability was high (α = .96).

Homework Problem Checklist (HPC; Anesko, Schoiock, Ramirez, & Levine, 1987) consists of 20 items on which parents rate the frequency and intensity of children’s homework problems (e.g., easily distracted, puts off starting) on a 4-point scale (0 = Never to 3 = Very Often). Baseline internal reliability was high (α = .92).

Covariates

Demographics

Gender and baseline grade were examined as covariates.

Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS; Pianta, La Paro, & Hamre, 2008) is a standardized measure of factors associated with effective classrooms (Pianta, Belsky, Houts, & Morrison, 2007). Observers were trained to provide quality scores on scale dimensions from 1 (low) to 7 (high) following 20-minute observations. Inter-rater reliability was assessed annually from master-coded DVDs to 80% criterion. The Classroom Organization factor (α = .77) was examined as a covariate.

Teacher Sense of Efficacy Scale (TSES; Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, 2001) has 12 items assessing teachers’ beliefs about their ability to effect student engagement and learning (1 = No Control to 9 = A Great Deal). The total score was examined as a covariate (α = .93).

Organizational Health Inventory - Elementary (OHI-E; Hoy & Woolfolk, 1993) consists of 37 items assessing teachers’ perceptions of organizational school health (1 = Rarely to 4 = Very Frequent). The total score was examined as a covariate (α = .95).

Quality of Teacher Work Life Survey (QTWLS; Pelsma, Richard, Harrington, & Burry, 1989) consists of 36 items to assess stress (1 = None; 4 = Extreme) and satisfaction (1 = Very Dissatisfied; 4 = Very Satisfied), The total score was examined as a covariate (α = .96).

Data Analysis

Three-level mixed-effects regression models (MRM; Hedeker & Gibbons, 2006) were used to examine condition effects (i.e., L2L vs. SAU) on child outcomes, and moderation of effects by baseline covariates. To assess effects over time, scores were coded for the number of months children were in classrooms of teachers who received the L2L professional development training. For all models, child-specific covariates (grade, gender) were entered at the child level, and teacher and classroom level covariates (CLASS, TSES, OHI-E, QTWLS) were entered at the classroom level. Significant covariates were retained in the final models. Model parameters were estimated using maximum marginal likelihood. Condition effects over time were estimated by the group X time interaction parameter. For outcome variables for which teacher-level random effects were not observed, two-level rather than three-level MRMs were computed. All MRMs were performed using Proc Mixed in SAS 9.2. Intent-to-treat analyses included a maximum of six measurement occasions for each of ten outcomes for 171 children in 117 classrooms in two conditions (L2L, SAU). Assessments took place in the fall and spring of each academic year.

Missing Data

Missing data occurred for three reasons: (1) child enrollment occurred after T1 assessment; (2) child was absent on a scheduled assessment or an instrument was not completed; (3) child moved to a school not involved in the study, or was withdrawn from the study by parents, or the school withdrew from the study. Data missing due to reason 3 occurred mainly after T4 for children who changed schools and after T2 for the six children who attended the school that withdrew from the study.

Imputation

For each variable with data missing, the number of measurement occasions with available data determined the maximum number of measurement occasions for which values were imputed (Hedeker & Gibbons, 1997). Thus, values were not imputed if they would have accounted for 50% or more of the data for a particular variable. Because BOSS was discontinued in the SAU condition after Year 1 (see Measures), BOSS data were not imputed beyond Year 1 for these children. Three methods were used to impute values for missing data, each pertaining to a different reason for missingness. For data missing due to reason 1, the season specific mean was used; for reason 2, the child-specific mean was used; for reason 3, the last observation carried forward (LOCF) was used. LOCF is widely used because the underlying implementation procedure is simple, as is its interpretation (Little & Rubin, 1987). For teacher-level missing data, the teacher-specific mean was imputed.

Results

Intent-to-Treat Analyses

Mental health service use

L2L children were significantly more likely than SAU children to enter into mental health services (72.1% of L2L children (75 of 104) and 28.4% of SAU children (19 of 67) entered services, χ2 = 9.96, p < .001) and to remain in services as indicated by one or more Medicaid billable session between a mental health service provider and client as indicated on agency review of records. Among children who received services, 52% (39 of 75) in the L2L condition received services until the conclusion of the study, compared to 15.8% (n = 3 of 19) in the SAU condition Z(1, N = 94) = 2.83, p < .01. There also was a significant difference in parent participation in services. For parents who received one or more service, parents in the L2L condition attended an average of 4.32 sessions per three-month period (SD = 4.35, range = 0.2 to 24.67), as compared to 2.02 sessions (SD = 2.11, range = 0.17 to 8.50) for parents in the SAU condition, t(92) = 2.23; p < .05 (ES = .71).

Behavioral outcomes

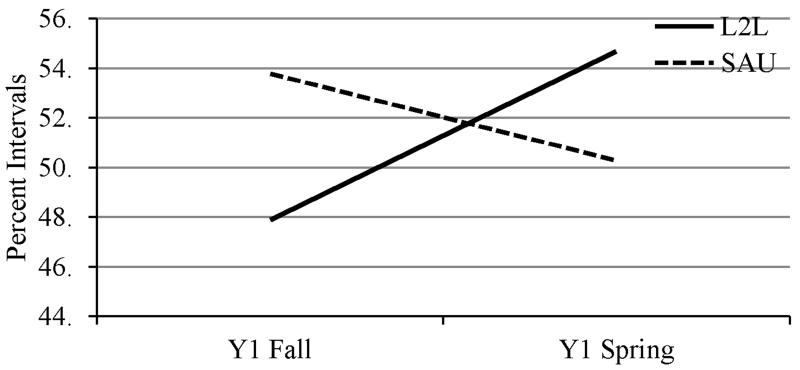

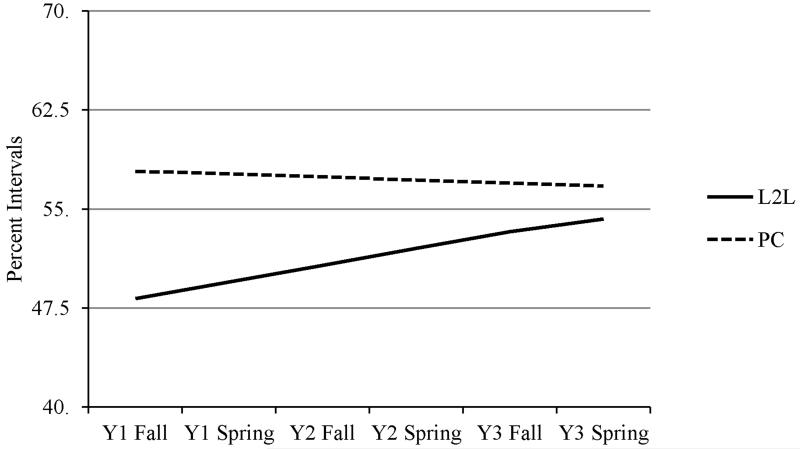

Table 2 presents descriptive statistics for child outcomes and Table 3 presents results from mixed effects models on behavioral outcomes including significant baseline covariates. There was a significant time by condition interaction for SSRS Social Skills indicating that L2L parents and teachers reported greater improvement in children’s social skills over time relative to SAU parents, t(628) = 2.28; p < .05, and teachers, t(296) = 2.14; p < .05. There was no SAU vs. L2L condition by time effect on BOSS observations of off task behavior. However, relative to peer comparisons (PC), L2L children demonstrated more off task behavior at baseline, t(742) = 10.65, p < .001, as expected, and showed larger decreases across three years, t(742) = −2.82, p < .01, ES = .53), controlling for gender. On BOSS academic engagement scores, L2L children, relative to SAU children, demonstrated significantly lower baseline scores, t(160) = −2.73, p = .01, and a steeper increase between time 1 and time 2, t(132) = 3.04, p < .01, ES = .60 (not shown in table). This significant between-group difference in slope over time is displayed in Figure 2A. In addition, as displayed in Figure 2B, L2L children again demonstrated expected lower BOSS academic engagement scores at baseline relative to PC, t(740) = −6.96, p < .001, ES = .32), and a greater rate of change over time controlling for grade and TSES, t(740) = 3.27, p < .01. There was no significant condition by time effect for SSRS Problem Behaviors (Teacher or Parent) or SDQ (Teacher or Parent).

Table 2. Behavioral and Academic Outcome Means and Standard Deviations across Time by Condition.

| Dependent Measures |

Baseline | Time 2 | Time 3 | Time 4 | Time 5 | Time 6 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SAU |

||||||

| BOSS Off Task | 59.25 (18.87) |

64.89 (15.30) |

||||

| BOSS Engagement* |

53.54 (18.00) |

47.91 (19.36) |

||||

| SSRS Prob. Beh (P) |

18.64 (6.05) | 18.61 (6.65) | 17.97 (6.03) |

17.62 (6.16) | 17.57 (6.10) | 17.91 (6.02) |

| SSRS Prob. Beh (T) |

19.65 (6.80) | 21.29 (4.92) | 20.25 (6.08) |

21.22 (6.15) | 20.32 (6.71) | 20.95 (5.85) |

| SSRS Social Skills (P) |

41.94 (10.90) |

43.97 (10.64) |

44.18 (10.99) |

44.91 (9.80) | 43.94 (10.42) |

44.48 (11.24) |

| SSRS Social Skills (T) |

24.7 (6.68) | 26.32 (6.42) | 24.57 (8.75) |

25.88 (8.82) | 25.55 (8.20) | 25.44 (7.56) |

| SDQ (P) | 3.28 (2.54) | 3.19 (2.44) | 3.29 (2.52) | 3.43 (2.57) | 3.18 (2.42) | 3.29 (2.59) |

| SDQ (T) | 3.07 (1.78) | 3.33 (1.62) | 3.42 (1.94) | 3.51 (1.84) | 3.63 (1.68) | 3.56 (1.80) |

| CBM | 34.69 (31.54) | 44.80 (35.22) | 46.10 (33.185) |

55.77 (41.08) | 51.20 (40.83) | 62.14 (42.58) |

| ACES* | 2.62 (0.80) | 2.73 (0.74) | 2.60 (0.77) |

2.62 (0.71) | 2.69 (0.73) | 2.61 (0.62) |

| Homework Prob. Checklist |

1.15 (0.65) | 1.14 (0.60) | 1.13 (0.63) |

1.19 (0.66) | 1.17 (0.64) | 1.23 (0.68) |

| L2L |

||||||

| BOSS Off Task | 56.99 (17.35) |

61.58 (19.43) |

58.16 (16.09) |

54.58 (19.37) |

57.54 (20.15) |

58.27 (21.42) |

| BOSS Engagement* |

46.05 (14.96) |

51.96 (20.33) |

51.58 (16.56) |

55.66 (19.56) |

54.01 (18.52) |

52.22 (22.22) |

| SSRS Prob. Beh (P) |

18.62 (6.63) | 19.43 (6.80) | 17.72 (6.66) |

19.05 (7.21) | 18.58 (7.45) | 18.77 (6.57) |

| SSRS Prob. Beh (T) |

17.82 (5.44) | 20.18 (6.36) | 18.86 (5.81) |

20.15 (6.56) | 19.14 (7.47) | 20.06 (7.53) |

| SSRS Social Skills (P) |

41.08 (11.66) |

45.95 (10.94) |

45.84 (12.16) |

47.35 (11.59) |

47.14 (11.82) |

47.43 (11.31) |

| SSRS Social Skills (T) |

22.27 (7.01) | 24.05 (7.88) | 24.66 (8.02) |

26.06 (9.92) | 25.73 (10.06) |

25.62 (10.21) |

| SDQ (P) | 3.33 (2.55) | 3.26 (2.85) | 3.03 (2.68) |

2.99 (3.03) | 3.26 (3.11) | 3.31 (3.09) |

| SDQ (T) | 2.64 (1.48) | 3.01 (1.72) | 2.73 (1.67) |

2.96 (1.77) | 2.56 (1.79) | 2.97 (1.65) |

| CBM | 39.77 (32.86) |

48.98 (37.27) |

42.00 (34.77) |

55.00 (41.97) |

42.63 (35.65) |

56.71 (42.97) |

| ACES* | 2.28 (0.81) | 2.51 (0.71) | 2.41 (0.75) |

2.54 (0.86) | 2.50 (0.84) | 2.50 (0.80) |

| Homework Prob. Checklist |

1.13 (0.66) | 1.29 (0.75) | 1.21 (0.74) |

1.28 (0.74) | 1.24 (0.73) | 1.23 (0.67) |

Note. P = Parent Report; T = Teacher Report; BOSS Engagement and BOSS Off Task collected only at baseline and time 2 for the SAU condition.

Indicates significant difference between L2L and SAU groups.

Table 3. MRM Parameter Estimates (Standard Errors) for Child Behavioral Outcomes Including Significant Covariates.

| SSRS Problem Behaviors (P) |

SSRS Problem Behaviors (T) |

SSRS Social Skills (P) |

SSRS Social Skills (T) |

SDQ (P) | SDQ (T) | BOSS Off Task (PC) |

BOSS Engagement (PC) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Effects |

||||||||

| Intercept | 18.51 (0.72) | 24.16 (1.72) | 42.77 (1.18) | 24.80 (0.82) | 3.57 (0.70)*** | 3.96 (0.54) | 43.59 (1.65) | 42.90 (4.93) |

| Intervention | −0.12 (0.93) | −1.25 (0.85) | −0.30 (1.52) | −1.46 (1.09) | 0.17 (0.36) | −0.23 (0.25) | 14.80 (1.39)*** | −9.68 (1.40)*** |

| Time | −0.21 (0.15) | 0.26 (0.14) | 0.48 (0.26) | 0.15 (0.18) | −0.11 (0.08) | 0.12 (0.05)** | 1.10 (0.41)** | −0.79 (0.44) |

| Time*Intervention | 0.24 (0.19) | 0.12 (0.18) | 0.77 (0.34)* | 0.49 (0.23)* | −0.05 (0.09) | −0.06 (0.06) | −1.29 (0.46)** | 1.50 (0.46)** |

| Random Effects |

||||||||

| Teacher intercept | N/A | 7.82 (2.43)** | N/A | 12.97 (3.82)** | N/A | 0.56 (0.17)** | 64.31 (19.66)** | 51.22 (16.05)** |

| Child intercept | 28.15(3.79)*** | 15.11 (2.50)*** | 76.68 (9.69)*** | 24.10 (4.07)*** | 3.92(0.52) *** | 1.09 (0.23)*** | 26.99 (15.02)* | 7.22 (12.27) |

| Child slope | 0.70(0.17)*** | 0.17 (0.16)* | 2.72 (0.52)*** | 0.32 (0.26)** | 0.16 (0.03)*** | 0.02 (0.02) | 4.81 (2.22)* | 3.90 (2.41) |

| Residual | 12.46 (0.70)*** | 9.33 (0.62)*** | 31.92 (1.84)*** | 15.89 (1.05)*** | 2.09(0.12)*** | 1.03 (0.07)*** | 175.36 (8.55)*** | 175.72 (8.64)*** |

| Effect Size (95% CI) |

.17(−.14,.48) | .08(−.22,.39) | .31(.001,.62) | .24(−.07,.55) | .08(−.23,.39) | .15(−.16,.46) | .32(.011,.63) | .4(.09,.71) |

Note. P = Parent Report; T = Teacher Report; PC = Peer Comparison. When teacher intercept did not contribute significant variance a two level model using the child intercept and child slope was used. These analyses only include significant covariates in the model. Effect size estimates for significant Time*Intervention effects.

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001.

Figure 2A.

Year 1 Child Observation (BOSS) of Engagement (L2L vs. SAU)

Figure 2B.

Child Observations (BOSS) of Engagement across Three Years (L2L vs. Peer Comparisons)

Academic outcomes

Table 4 presents the three-level mixed effects models on teacher ratings of academic performance including significant baseline covariates. For ACES, there was a significant difference at baseline between L2L and SAU children, t(296) = −2.87, p < .01, and a condition by time interaction favoring the L2L group, t(296) = 2.432, p < .05, indicating a greater improvement in teacher reported academic competence over time. There were no condition differences on the HPC or CBM reading fluency.

Table 4. MRM Parameter Estimates (Standard Errors) for Child Academic Outcomes Including Significant Covariates.

| ACES | CBM | Homework Prob. Checklist |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Effects |

|||

| Intercept | 2.65 (0.08) | 44.57 (9.95) | 0.98 (0.08) |

| Intervention | −0.32 (0.11)** | 9.38(4.68)* | 0.07 (0.09) |

| Time | −0.01 (0.01) | 4.99 (0.57)*** | −0.02 (0.02) |

| Time*Intervention | 0.04 (0.02)** | −1.28 (0.72) | −0.002 (0.02) |

| Random Effects |

|||

| Teacher intercept | .12 (.04)** | 156.47 (74.26)* | 0.04 (0.02)* |

| Child intercept | 0. .39 (.05)*** | 775.8 (96.7)*** |

0.37 (0.05)*** |

| Child slope | 0.001 (0.002) | 12.10 (2.73)*** | 0.01(0.003)** |

| Residual | 0.10 (0.01)*** | 52.11 (3.98)*** | 0.07 (0.005)*** |

| Effect Size (95% CI) |

.27(−.04,.58) | .17(−.14,.48) | .02(−.29,.32) |

Note. When teacher intercept did not contribute significant variance a two level model using the child intercept and child slope was used. These analyses only include significant baseline covariates in the model. Effect size estimates for significant Time*Intervention effects.

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001.

Moderation Analyses

Table 5 presents MRM analyses examining moderation of condition by time effects by grade, gender, parent hassles, child impairment (SDQ Parent Impact Scale, SDQ Teacher Impact Scale), and child academic competence (SSRS Teacher Report). Separate models were run for each outcome with significant intervention by time effects (i.e., ACES, SSRS Social Skills Parent, BOSS Engagement, and BOSS Off Task.

Table 5. MRM Parameter Estimates (Standard Errors) for Significant Moderators of L2L Behavioral and Academic Outcomes.

| ACES | SSRS Social Skills (P) |

SSRS Social Skills (P) |

SSRS Social Skills (T) |

BOSS Engagement |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Effects |

|||||

| Intercept | 2.59(.09) | 42.40(1.19)*** | 43.53(1.28)*** | 24.22(.88) | 53.57(2.39) |

| Time | −0.02(.01) | 0.50(0.26) | 0.49(0.27) | 0.05(.18) | −5.59(2.61) ** |

| Intervention | −0.32(0.11)** | 0.57(1.53) | −0.24(1.56) | −1.4(1.08) | −7.27(2.92) ** |

| Time * Intervention | 0.11(0.02) *** | 0.61(0.34) | 0.50(0.37) | 0.95(.30)** | 7.60(3.67) |

| SDQ (T) | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Parent Hassles | -- | 5.06(0.89) *** | -- | -- | -- |

| Gender (female = 1) | -- | -- | −3.04(1.67) | -- | .31(2.66) |

| Grade | 0.13(0.06) * | -- | -- | 1.24(.68) | -- |

| Time*Intervention*SDQ | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Time*Intervention*Hassles | -- | −1.25(0.42) ** | -- | -- | -- |

| Time*Intervention*Gender | -- | -- | 0.97(0.47) * | -- | 12.35(5.34) ** |

| Time*Intervention*Grade | −0.10(0.02)*** | -- | -- | −0.64(.27)* | -- |

Note. Moderators were entered into the model individually for each outcome measure. Displayed are values associated with significant moderation results. Dashed lines indicate nonsignificant parameter estimates. P = Parent Report; T = Teacher Report. BOSS Engagement was analyzed for Year 1 only, with children from SAU schools rather than in-class peers modeled as the comparison group.

p < 0.05;

p < 0.01;

p < 0.001.

There was a significant three-way interaction between baseline symptom severity (teacher report), condition, and time such that teachers reported greater improvement in academic competence for L2L children identified as less impaired, t(275) = −2.79, p < .01. Parents of L2L children who reported more hassles reported less improvement over time in their child’s social skills when compared to parents of L2L children who reported fewer hassles (t(615) = −2.96, p < .01). On SSRS Social Skills (parent), parents of L2L girls reported greater improvement over time in social skills than parents of L2L boys (t(628) = 2.05, p < .05). On BOSS academic engagement scores, L2L girls demonstrated greater improvement than L2L boys between time 1 and time 2 (t(114) = 2.55, p < .05). L2L children in lower grades (K-2nd) at baseline demonstrated greater improvement in teacher report of academic competence (ACES) and social skills (SSRS) than L2L children in higher (3rd-4th) baseline grades (t(573) = −4.63, p < .0001 and t(294) −2.33, p <.05 respectively).

Discussion

This study is part of a broader program of research focused on re-designing mental health services to support children’s learning within communities of concentrated urban poverty (Atkins, Rusch, Mehta, & Lakind, 2015). Based on empirical evidence indicating that schooling is a critical component of children’s mental health, we hypothesized that community mental health services directly targeting the empirical predictors of children’s learning would lead to improved behavior at home and school compared to mental health services as usual. In a longitudinal two-group design with matched schools randomly assigned to conditions, this hypothesis was largely supported.

Robust effects on service initiation and retention favoring L2L replicated those found in a prior study (Atkins et al., 2006) indicating advantages for school-based over clinic-based services for families in high poverty urban communities. In the current study, these differences were large and enduring, with more than one half of L2L families receiving services and 75% of families who remained in the L2L school electing to continue them. For those families who received mental health services, parent participation in sessions was twice as high for L2L versus SAU conditions. In L2L, services were provided in the primary contexts of learning and behavior -- classrooms and homes -- rather than in mental health clinics, and focused directly on helping teachers and parents to support child learning, thereby minimizing concrete barriers such as transportation and childcare. Because mental health services were delivered by community mental health providers and reimbursed by Medicaid fee-for-service billing, these results suggest that re-designing mental health services to support children’s learning increased the accessibility and sustainability of community-based services in these high poverty settings.

Second, results indicated that leveraging mental health services to support children’s learning resulted in improved school behavior. L2L children demonstrated greater increases than SAU children in classroom observations of academic engagement in Year 1, and approached levels of normative peers on engagement and off task behavior across three years with moderate to large effect sizes across analyses. These results are especially notable given evidence for the protective effect of school success for children in urban poverty (Freudenberg & Ruglis, 2007).

Third, relative to SAU, L2L was associated with small but significant increases in teacher-rated academic competence (d = .29), and social skills rated by teachers (d = .24), and parents (d = .27), particularly for children in lower grades and those with less severe impairment. Thus, L2L may be best considered as an early intervention, consistent with research on several of its components (e.g., Embry, 2002; Ginsburg-Block, Rohrbeck, & Fantuzzo, 2006). These effect sizes were equal to or greater than treatments for ethnic minority youth (mean ES = .22 compared to SAU; Huey & Polo, 2008), for a CBT intervention for disadvantaged youth (mean ES = .31 compared to wait-list; Liber, De Boo, Huizenga, & Prins, 2013), and for the three year evaluation of the Fast Track intervention for children at risk for conduct problems (mean ES = .19 compared to no-treatment controls; Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 2002).

However, despite improved on task behavior and teacher reported academic competence for children in the L2L condition, reading fluency did not improve as measured objectively by curriculum-based probes. This suggests that L2L affected proximal (e.g., engagement) but not distal (i.e., achievement) outcomes. Perhaps to impact achievement directly, future iterations of the model need to incorporate curriculum modifications and differentiated instructional approaches, especially when a child’s instructional level deviates significantly from their grade level (Harrison, Bunfort, Evans, & Owens, 2013). These approaches could be incorporated into KOL-led professional development meetings, which appeared to be an important component of the service delivery model by promoting collaboration between MHPs and teachers as well as strengthening MHPs’ familiarity with effective educational practices; a new role for MHPs and potentially a powerful support to teachers, children, and parents.

Additional analyses indicated moderation effects for level of behavioral difficulty and family stress. This may suggest the need for more intensive services for the most behavior-disordered children with future iterations of L2L incorporating more intensive family support for a subset of high need families (e.g., Dagenais, Begin, Bouchard, & Fortin, 2004). Because the universal and targeted interventions of L2L comprise the first two tiers of a public health model, adding more intensive services could facilitate greater gains and wider reach for children and families than delivering services independently (Atkins & Frazier, 2011; Stiffman et al., 2010).

Finally, these findings have implications for health care reform in an era of universal mental health coverage. As noted by Mechanic (2012), the Affordable Care Act provides many opportunities to align service models more directly with important outcomes and to improve access to high quality prevention and intervention services. We suggest that this study supports a direct focus on children’s learning as a realistic goal of community mental health services, and also the development of novel workforce teams (Schoenwald, Ringeisen, Hoagwood, Evans, & Atkins, 2010). In our study, classroom teachers and parent advocates worked collaboratively with community mental health providers and made important contributions to the service model. Furthermore, although L2L was maintained through fee-for-service Medicaid billing, alternative funding mechanisms such as capitated care models that fund outcomes not services may be able to facilitate even greater collaboration among service team members (Lehman, 1987).

Limitations and Future Directions

The study had a number of limitations. First, classroom observational data were not collected in the SAU condition beyond the first year due to concerns expressed by teachers regarding the amount of time observers were spending in their classrooms. Because no such concerns were expressed by L2L teachers, and given our long-standing relationship with schools in this district, we chose to withdraw observers from SAU schools to accommodate these concerns while retaining observations in the L2L condition. Although the results from the first year indicated robust differences between groups in favor of the L2L condition and subsequent peer comparison data provided evidence that L2L children were approaching normative peer behavior, future research that includes longitudinal observational data between targeted groups would strengthen findings. Second, because the intervention was designed to last several years, we were unable to conduct follow-up assessments to determine long-term outcomes. Third, although schools and agencies were similar in composition and structure, there were too few schools or agencies to examine setting-level effects including the extent to which organizational social context impacted outcomes (Glisson et al., 2007). Replication in a larger number of schools and agencies would be an important additional step in the research.

In summary, this is the largest and longest study of urban children’s mental health service use and school performance to date and suggests that redesigning community mental health services to support learning and behavior among urban low-income children is a feasible and effective alternative to SAU. Consistent with diffusion theory, the model leveraged the influence of key opinion leader teachers and influential parents on teacher and parent use of services. Results suggest that aligning community mental health resources with school goals and directly targeting key empirical home and school predictors of learning can improve outcomes for children living in high poverty urban communities.

Public Health Significance Statement.

This study leveraged the influence of key opinion leader teachers and parent advocates to re-design community mental health services to target the empirical predictors of children’s learning for children referred for disruptive behavior disorder living in high poverty urban communities. Results suggest that this model increases the accessibility, effectiveness, and sustainability of mental health services relative to community mental health services as usual.

Acknowledgments

This research was conducted with support from National Institute of Mental Health grants R21MH067361, R01MH073749, and P20MH078458 (Marc S. Atkins, PI).

Contributor Information

Marc S. Atkins, Department of Psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago

Elisa S. Shernoff, Department of Psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago

Stacy L. Frazier, Department of Psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago

Sonja K. Schoenwald, Department of Psychiatry, Medical University of South Carolina

Elise Cappella, Department of Applied Psychology, New York University

Ane Marinez-Lora, Department of Psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago.

Tara G. Mehta, Department of Psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago

Davielle Lakind, Department of Psychology, University of Illinois at Chicago.

Grace Cua, Department of Psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago.

Runa Bhaumik, Department of Psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago.

Dulal Bhaumik, Department of Psychiatry, University of Illinois at Chicago.

References

- Anesko K, Schoiock G, Ramirez R, Levine F. The homework problem checklist: Assessing children’s homework difficulties. Behavioral Assessment. 1987;9:179–185. [Google Scholar]

- Atkins MS, Frazier SL. Expanding the toolkit or changing the paradigm: Are we ready for a public health approach to mental health? Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2011;6:483–487. doi: 10.1177/1745691611416996. doi:10.1177/1745691611416996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins M, Frazier S, Birman D, Adil J, Jackson M, Graczyk P, Talbott E, McKay M. School-based mental health services for children living in high poverty urban communities. Administration and Policy in Mental Health & Mental Health Services Research. 2006;33:146–159. doi: 10.1007/s10488-006-0031-9. doi:10.1007/s10488-006-0031-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins M, Frazier S, Leathers S, Graczyk P, Talbott E, Adil J, Marinez-Lora A, Gibbons R. Teacher key opinion leaders and mental health consultation in urban low-income schools. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008;76:905–908. doi: 10.1037/a0013036. doi:10.1037/a0013036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins M, Hoagwood K, Kutash K, Seidman E. Towards the integration of education and mental health in schools. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2010;37:40–47. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0299-7. doi:10.1007/s10488-010-0299-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins MS, Lakind D. Usual care for clinicians, unusual care for their clients: Rearranging priorities for children’s mental health services. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2013;40:48–51. doi: 10.1007/s10488-012-0453-5. doi:10.1007/s10488-012-0453-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atkins MS, Rusch D, Mehta TG, Lakind D. Future directions for dissemination and implementation science: Aligning ecological theory and public health to close the research to practice gap. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2015 doi: 10.1080/15374416.2015.1050724. doi:10.1080/15374416.2015.1050724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrish H, Saunders M, Wolf MM. Good behavior game: Effects of individual contingencies for group consequences on disruptive behavior in a classroom. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. 2:119–124. doi: 10.1901/jaba.1969.2-119. doi:10.1901/jaba.1969.2-119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borofsky L, Kellerman I, Baucom B, Oliver P, Margolin G. Community violence exposure and adolescents’ school engagement and academic achievement over time. Psychology of Violence. 2013;3:381. doi: 10.1037/a0034121. doi:10.1037/a0034121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappella E, Frazier S, Atkins M, Schoenwald S, Glisson C. Enhancing schools’ capacity to support children in poverty: An ecological model of school-based mental health services. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2008;35:395–409. doi: 10.1007/s10488-008-0182-y. doi:10.1007/s10488-008-0182-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group Evaluation of the first 3 years of the Fast Track prevention trial with children at high risk for adolescent conduct problems. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2002;30:19–35. doi: 10.1023/a:1014274914287. doi:10.1023/A:1014274914287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dagenais C, Begin J, Bouchard C, Fortin D. Impact of intensive family support programs: A synthesis of evaluation studies. Children and Youth Services Review. 2004;26:249–263. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2004.01.015. [Google Scholar]

- DeLongis A, Folkman S, Lazarus R. The impact of daily stress on health and mood: Psychological and social resources as mediators. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1988;54:486–495. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.54.3.486. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.54.3.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempster R, Wildman B, Keating A. The role of stigma in parental help-seeking for child behavior problems. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2013;42:56–67. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.700504. doi:10.1080/15374416.2012.700504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiPerna JC, Elliott SN. Development and validation of the academic competence evaluation scales. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment. 1999;17:207–225. doi:10.1177/073428299901700302. [Google Scholar]

- Embry DD. The good behavior game: A best practice candidate as a universal behavioral vaccine. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2002;5:273–297. doi: 10.1023/a:1020977107086. doi:10.1023/A:1020977107086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epstein M, Atkins M, Cullinan D, Kutash K, Weaver R. Reducing behavior problems in the elementary school classroom: A practice guide. National Center for Education Evaluation and Regional Assistance, Institute of Education Sciences, U.S. Department of Education; Washington, DC: 2008. NCEE #2008-012. [Google Scholar]

- Farahmand F, Duffy S, Tailor M, DuBois D, Lyon A, Grant K, Nathanson A. Community-based mental health and behavioral programs for low-income, urban youth: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2012;19:195–215. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2850.2012.01283.x. [Google Scholar]

- Farahmand F, Grant K, Polo A, Duffy S, DuBois D. School-based mental health and behavioral programs for low-income, urban youth: A systematic and meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2011;18:372–390. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2850.2011.01265.x. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer E, Burns B, Phillips S, Angold A, Costello E. Pathways into and through mental health services for children and adolescents. Psychiatric Services. 2003;54:60–66. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.1.60. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.54.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer E, Compton S, Burns B, Robertson E. Review of the evidence for treatment of childhood psychopathology: Externalizing disorders. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2002;70:1267–1302. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.70.6.1267. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.70.6.1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flower A, McKenna J, Bunuan R, Muething C, Vega R. Effects of the Good Behavior Game on challenging behaviors in school settings. Review of Educational Research. 2014;84:546–571. doi:10.3102/0034654314536781. [Google Scholar]

- Foster S, Rollefson M, Doksum T, Noonan D, Robinson G, Teich J. School mental health services in the United States, 2002–2003. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Rockville, MD: 2005. DHHS Pub. No. (SMA) 05-4068. [Google Scholar]

- Freudenberg N, Ruglis J. Reframing school dropout as a public health issue. Preventing Chronic Disease. 2007;4(4):1–11. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frazier S, Abdul-Adil J, Atkins M, Gathright T, Jackson M. Can’t have one without the other: Mental health providers and community parents reducing barriers to services for families in urban poverty. Journal of Community Psychology. 2007;35:435–446. doi:10.1002/jcop.20157. [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs D, Fuchs L, Burish P. Peer-assisted learning strategies: An evidence-based practice to promote reading achievement. Learning Disabilities Research & Practice. 2000;15:85–91. doi:10.1207/SLDRP1502_4. [Google Scholar]

- Ginsburg-Block M, Rohrbeck C, Fantuzzo J. A meta-analytic review of social, self-concept, and behavioral outcomes of peer assisted learning. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2006;98:732–749. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.98.4.732. [Google Scholar]

- Glisson C, Landsverk J, Schoenwald S, Kelleher K, Hoagwood K, Mayberg S, Green P. Assessing the organizational social context (OSC) of mental health services: Implications for research and practice. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2007;35:95–113. doi: 10.1007/s10488-007-0148-5. doi:10.1007/s10488-007-0148-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodman R. Psychometric properties of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:1337–1345. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200111000-00015. doi:10.1097/00004583-200111000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodnight J, Lahey B, Van Hulle C, Rodgers J, Rathouz P, Waldman I, D’Onofrio B. A quasi-experimental analysis of the influence of neighborhood disadvantage on child and adolescent conduct problems. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2012;121:95–108. doi: 10.1037/a0025078. doi:10.1037/a0025078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green J, McLaughlin K, Alegria M, Costello E, Gruber M, Hoagwood K, Kessler R. School mental health resources and adolescent mental health service use. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013;52:501–510. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.03.002. doi:10.1016/j.jaac.2013.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresham FM, Elliott SN. The Social Skills Rating System. American Guidance Service; Circle Pines, MN: 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison JR, Bunford N, Evans SW, Owens JS. Educational accommodations for students with behavioral challenges: A systematic review of the literature. Review of Educational Research. 2013;83:551–597. doi:10.3102/0034654313497517. [Google Scholar]

- Harrison ME, McKay MM, Bannon WM., Jr. Inner-city child mental health service use: The real question is why youth and families do not use services. Community Mental Health Journal. 2004;40:119–131. doi: 10.1023/b:comh.0000022732.80714.8b. doi:10.1023/B:COMH.0000022732.80714.8b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hedeker D, Gibbons RD. Application of random-effects pattern-mixture models for missing data in longitudinal designs. Psychological Methods. 1997;2:64–78. doi:10.1037/1082-989X.2.1.64. [Google Scholar]

- Hedeker D, Gibbons RD. Longitudinal data analysis. Wiley; Hoboken, NJ: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Henggeler S, Schoenwald S, Borduin C, Rowland M, Cunningham P. Multisystemic treatment of antisocial behavior in children and adolescents. Guilford; NY: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Hoagwood K, Cavaleri M, Olin S, Burns B, Slaton E, Gruttadaro D, Hughes R. Family support in children’s mental health: A review and synthesis. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review. 2010;13:1–45. doi: 10.1007/s10567-009-0060-5. doi:10.1007/s10567-009-0060-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoy WK, Woolfolk AE. Teachers’ sense of efficacy and the organizational health of schools. The Elementary School Journal. 1993;93:355–372. doi:10.1086/461729. [Google Scholar]

- Huey SJ, Polo AJ. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for ethnic minority youth. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:262–301. doi: 10.1080/15374410701820174. doi:10.1080/15374410701820174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeynes WH. A meta-analysis of the relation of parental involvement to urban elementary school student academic achievement. Urban Education. 2005;40:237–269. doi:10.1177/0042085905274540. [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka S, Zhang L, Wells K. Unmet need for mental health care among U.S. children: Variation by ethnicity and insurance status. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:1548–1555. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1548. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley ML, McCain A. Promoting academic performance in inattentive children: The relative efficacy of school-home notes with and without response cost. Behavior Modification. 1995;19:357–375. doi: 10.1177/01454455950193006. doi:10.1177/01454455950193006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Gendrich JG, Gendrich SI, Schnelle JF, Gant DS, McNees MP. An evaluation of daily report cards with minimal teacher and parent contacts as an efficient method of classroom intervention. Behavior Modification. 1977;1:381–394. doi:10.1177/014544557713006. [Google Scholar]

- Lehman AF. Capitation payment and mental health care: A review of the opportunities and risks. Psychiatric Services. 1987;38:31–38. doi: 10.1176/ps.38.1.31. doi:10.1176/ps.38.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liber J, De Boo G, Huizenga H, Prins P. School-based intervention for childhood disruptive behavior in disadvantaged settings: A randomized controlled trial with and without active teacher support. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2013;81:975–987. doi: 10.1037/a0033577. doi:10.1037/a0033577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Little RJ, Rubin DB. Statistical analysis with missing data. Wiley; New York: 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Masten A, Curtis W. Integrating competence and psychopathology: Pathways toward a comprehensive science of adaptation in development. Development and Psychopathology. 2000;12:529–550. doi: 10.1017/s095457940000314x. doi:10.1017/S095457940000314X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechanic D. Seizing opportunities under the Affordable Care Act for transforming the mental health and behavioral health system. Health Affairs. 2012;31:376–382. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0623. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2011.0623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy DC, Roy AL, Sirkman GM. Neighborhood crime and school climate as predictors of elementary school academic quality: A cross-lagged panel analysis. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2013;52:128–140. doi: 10.1007/s10464-013-9583-5. doi:10.1007/s10464-013-9583-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McKay MM, Bannon WM. Engaging families in child mental health services. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2004;13:905–921. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2004.04.001. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Advisory Mental Health Council . Blueprint for Change: Research on Child and Adolescent Mental Health. Author; Washington D.C.: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Neal JW, Neal Z, Atkins MS, Henry D, Frazier SL. Channels of change: Contrasting network mechanisms in the use of interventions. American Journal of Community Psychology. 2011;47:277–286. doi: 10.1007/s10464-010-9403-0. doi:10.1007/s10464-010-9403-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neal JW, Shernoff ES, Frazier SL, Stachowicz E, Frangos U, Atkins MS. Change from within: Engaging teacher key opinion leaders in the diffusion of interventions in urban schools. The Community Psychologist. 2008;41:53–57. [Google Scholar]

- Patall EA, Cooper H, Robinson JC. Parent involvement in homework: A research synthesis. Review of Educational Research. 2008;78:1039–1101. doi:10.3102/0034654308325185. [Google Scholar]

- Pelham W, Gnagy E, Greenslade K, Milich R. Teacher ratings of DSM-III-R symptoms for the disruptive behavior disorders. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 1992;31:210–218. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199203000-00006. doi:10.1097/00004583-199203000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelsma D, Richard G, Harrington R, Burry J. The quality of teacher work life survey: A measure of teacher stress and job satisfaction. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development. 1989;21:165–176. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC, Belsky J, Houts R, Morrison F. Opportunities to learn in America’s elementary classrooms. Science. 2007;315:1795–1796. doi: 10.1126/science.1139719. doi:10.1126/science.1139719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC, La Paro KM, Hamre BK. The Classroom Assessment Scoring System. Paul H. Brookes Publishing; Baltimore: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Reardon S. The widening academic achievement gap between the rich and the poor: New evidence and possible explanations. In: Duncan G, Murnane R, editors. Whither opportunity?: Rising inequality, schools, and children’s life chances. Russell Sage Foundation; NY: 2011. pp. 91–116. [Google Scholar]

- Ringeisen H, Henderson K, Hoagwood K. Context matters: Schools and the research to practice gap in children’s mental health. School Psychology Review. 2003;32:153–168. [Google Scholar]

- Roeser R, Eccles J, Freedman-Doan Academic functioning and mental health in adolescence: Patterns, progressions, and routes from childhood. Journal of Adolescent Research. 1999;14:135–174. doi: 10.1177/0743558499142002. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers EM. Diffusion of innovation. 4th Ed. The Free Press; NY: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Rohrbeck C,A, Ginsburg-Block M,D, Fantuzzo JW, Miller TR. Peer-assisted learning interventions with elementary school students: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2003;95(2):240–257. doi:10.1037/0022-0663.95.2.240. [Google Scholar]

- Rones M, Hoagwood K. School-based mental health services: A research review. Clinical Child & Family Psychology Review. 2000;3:223–241. doi: 10.1023/a:1026425104386. doi:10.1023/A:1026425104386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald SK, Mehta TG, Frazier SL, Shernoff ES. Clinical supervision in effectiveness and implementation research. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. 2013;20:44–59. doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12022. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenwald SK, Ringeisen H, Hoagwood K, Evans M, Atkins M. Workforce development and the organization of work: The science we need. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2010;37:71–80. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0278-z. doi:10.1007/s10488-010-0278-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serpell R, Sonnenschein S, Baker L, Ganapathy H. Intimate culture of families in the early socialization of literacy. Journal of Family Psychology. 2002;16:391–405. doi:10.1037/0893-3200.16.4.391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro E. Academic skills problems: Direct assessment and intervention. Guilford; NY: 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan SM, Kratochwill TR. Conjoint behavioral consultation: Promoting family-school connections and interventions. Springer; NY: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Stiffman A, Stelk W, Evans M, Atkins M. A public health approach to children’s mental health services: Possible solutions to current service inadequacies. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research. 2010;37:120–124. doi: 10.1007/s10488-009-0259-2. doi:10.1007/s10488-009-0259-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]