Summary

Background

In recent years, many localities within the Greater Accra Region (GAR) have witnessed several episodes of cholera outbreaks, with some deaths. Compared to previous epidemics, which usually followed heavy rains, recent outbreaks show no seasonality.

Objectives

To investigate infective bacterial diseases in selected sub metros within the GAR.

Methods

We used existing disease surveillance systems in Ghana, and investigated all reported cases of diarrhoea that met our case-definition. A three-day training workshop was done prior to the start of study, to sensitize prescribers at the Korle-Bu Polyclinic and Maamobi General hospital. A case-based investigation form was completed per patient, and two rectal swabs were taken for culture at the National Public Health and Reference Laboratory. Serotyping and antibiogram profiles of identified bacteria were determined. Potential risk factors were also assessed using a questionnaire.

Results

Between January and June 2012, a total of 361 diarrhoeal cases with 5 deaths were recorded. Out of a total of 218 rectal swabs cultured, 71 (32.6%) Vibrio cholerae O1 Ogawa serotypes, and 1 (0.5%) Salmonella (O group B) were laboratory confirmed. No Shigella was isolated. The Vibrio cholerae isolates were susceptible to ciprofloxacin and tetracycline. Greater than 80% of patients reported having drank sachet water 24 h prior to diarrhoea onset, and many (144/361) young adults (20–29 years) reported with diarrhoea.

Conclusion

Enhanced surveillance of diarrhoeal diseases (enteric pathogens) within cholera endemic regions, will serve as an early warning signal, and reduce fatalities associated with infective diarrhoea.

Keywords: Diarrhoeal disease surveillance, enteric pathogens, Vibrio cholerae, Salmonella

Introduction

Diarrhoeal diseases remain a prevalent cause of morbidity and mortality globally.1 In recent years however, mortality due to diarrhoea has declined, but not in parallel to morbidity, especially in developing countries.2 Contaminated food and water are major sources for the transmission of diarrhoeal disease agents, and also contribute to the spread of epidemics. 3 Globally, species of Vibrio, Salmonella, Shigella and Shiga toxin producing Escherichia coli have been implicated in major epidemics. 4–6 Many countries therefore have surveillance systems in place for early warning signal of epidemics arising from these bacteria.

In Ghana, there is a national disease surveillance system for reporting human notifiable diseases, including cholera, shigellosis and salmonellosis. This system uses the Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (IDSR) approach and is often passive, adapted by the World Health Organization (WHO/AFRO) member states.7

In recent years, high case fatality rates of cholera epidemics have been reported in Ghana and most African countries.8 Between January and November 2011 for example, a total of 105, 222 cholera cases and 2, 912 deaths were reported from 25 countries in the WHO African region, resulting in a case fatality rate (CFR) of 2.8%.

Five countries, including Nigeria, Cameroon, DR Congo, Chad and Ghana accounted for 87% (91 688/105 222) of the total number of cases, and 89% (2 589 / 2 912) of the total number of deaths recorded.9

Cholera epidemics have been known to typically occur every five years in Ghana, following heavy rains and flooding or acute water shortages. Contrarily however, in the last few years, both sporadic and epidemic cases of cholera have been reported in Ghana with onsets following no seasonality. 10 Initiatives aimed at controlling infective diarrhoea in a population should be based on the extent of the problem. However, the true incidence of diarrhoea in Ghana, based on data from national disease surveillance systems is usually underestimated. Several factors, including lack of motivation on the part of prescribers to request for stool culture, and poor diagnostic capabilities at the facility level can account for this.

A progressive active Diarrhoeal Diseases Surveillance (DDS) system is required for the early detection of diseases, especially in epidemic prone regions. Weak DDS in cholera epidemic prone regions ultimately results in needless case fatalities. In this pilot study, we performed an active surveillance, investigating all reported cases of diarrhoea in two selected submetros within the GAR.

Materials and Methods

Sites selection

The Greater Accra Region of Ghana has six sub-metropolitan health areas. For routine disease surveillance, health facilities within these sub metros periodically send specimens together with completed IDSR case investigation form to the National Public Health and Reference Laboratory (NPHRL) for laboratory confirmation. Data is also usually transferred from the various surveillance systems within the community, sub-district, district, regional and national levels. For this pilot study, two prescriber facilities, Korle-Bu Polyclinic and Maamobi General Hospital were selected for an enhanced surveillance of diarrhoeal diseases, following the 2011 cholera epidemic in Ghana. These two sites were conveniently chosen, and proximity to the NPHRL and high catchment population size (recorded the highest proportion of cases during the 2011cholera epidemic) were the key considerations. These two facilities serve an approximate catchment population size of 2,199,908 (by 2000 census and projected by 4.4%). 11

Prior to commencement of this study, training/retraining of all prescribers, including medical officers, nurses, surveillance officers and biomedical scientists within the two selected sites was done. The purpose of the 3-day training was basically to sensitize prescribers and to increase participation and cooperation.

Emphasis was also placed on diarrhoea case definition, specimen collection and transportation, specimen processing, data capture, primary analyses and reporting at the facility levels.

Case-definition and patient selection

We used the existing surveillance system for diarrhoea reporting in Ghana. However, every patient presenting with diarrhoea at the two selected facilities, who fitted our case-definition was enrolled and investigated. Diarrhoea was defined as the passage of three or more watery or loose stools per 24 h period with a duration lasting less than 14 days. Our case-definition for patient selection was acute watery or bloody diarrhoea with/without clinical symptoms. Fever (axial temperature ≥ 38.0°C), abdominal cramps, nausea and vomiting were the clinical symptoms considered.

Stool collection and processing

Disease Control Officers at the facility levels completed a case-based investigation form for every consenting patient. Two rectal swabs were taken per patient by a nurse/Disease control officer, and kept in a Cary Blair transport medium prepared by the NPHRL. Rectal swabs together with completed case-based investigation forms were sent to the NPHRL for analyses. The case-based investigation form captured information relating to patient locality, demographics, food and water taken 24 h prior to diarrhoea onset and clinical presentation of the diarrhoea.

We followed a detailed protocol and cultured stool specimens for Vibrio cholerae, Salmonella and Shigella at the NPHRL. Rectal swabs were inoculated directly onto MacConkey (MaC), Deoxychocolate (DCA) and Thiosulfate Citrate-Bile-Sucrose (TCBS) agars purchased from Lab M Ltd (Lancashire, UK). Each of the two swabs was also cultured in selenite F broth (SF) and alkaline peptone water (APW), for the enrichment of Salmonella and Vibrio, respectively.

Agar plates and broths were incubated under aerobic conditions at 37°C for 18 – 20 h. Broth cultures in SF and APW were inoculated onto DCA and TCBS plates, respectively, after 18-20 h incubation. Non-lactose fermenters on MaC and DCA, and colonies on TCBS resembling those of Vibrio were sub cultured onto Tryptone Soy agar (TSA), for routine biochemical tests. 12

Serotyping of Vibrio cholerae and Salmonella were done using commercial antisera purchased from Deben diagnostics Ltd (Suffolk, UK) and Sifin (Berlin, Germany), respectively. We did not investigate Campylobacter and Escherichia coli O157.

Antimicrobial susceptibility test was performed using the Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion method 13 and interpretation was done according to the protocols of the Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute [CLSI, 2010]. 14 The following antimicrobials with their disc concentrations were tested; nalidixic acid (30µg), ciprofloxacin (5µg), chloramphenicol (30µg), ampicillin (10µg), tetracycline (30µg), erythromycin (15 µg) and cotrimoxazole (25 µg). The antimicrobials were purchased from Becton, Dickinson and company (USA). Confirmed laboratory reports were transferred from the NPHRL through the various reporting levels within the surveillance systems back to the prescriber points. This enhanced surveillance spanned twenty-six week duration, January to June 2012.

Data analysis

Data was entered into an Epi Info template at the sub-metro level, and was sent weekly to the regional level via e-mail. Additionally, final data was collated and analyzed at the Disease Surveillance Department of the Ghana Health Service, using Microsoft excel and Epi-Info version 10 (CDC, Atlanta, USA). Information analyzed included weekly epidemiological data, patient's demographics, clinical symptoms and laboratory results.

Results

Between January and June 2012, a total of 361 diarrhoeal cases with 5 deaths (overall CFR=1.4%) were recorded at the two pilot sites. Korle-Bu Polyclinic recorded the highest proportion of the diarrhoeal cases; 68.9% (249 cases, 3 deaths, CFR= 1.2%). Maamobi General Hospital recorded 31.1% (112 cases, 2 deaths, CFR= 1.8%)..

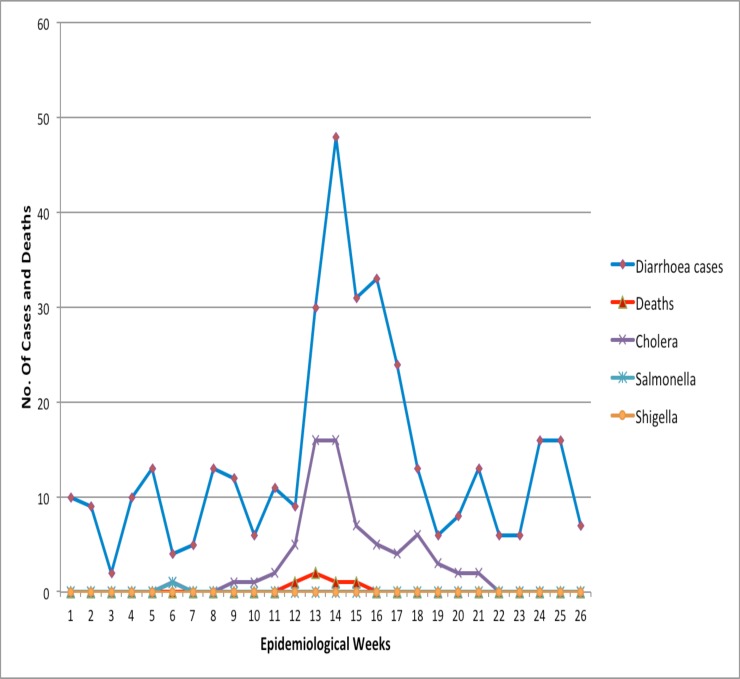

The deaths recorded were associated with Vibrio cholerae (4 deaths) and salmonella infection (1 death). Reported diarrhoeal cases were observed during week one (1) and peaked at week 14, with a corresponding rise in confirmed cholera cases (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Weekly trends of diarrhoeal cases, deaths and organisms reported from Korle-Bu Polyclinic and Maamobi General Hospital, Accra Metropolis, 1 January to 31 June 2012

Out of 218 rectal swabs cultured for enteric pathogens, 71 (32.6%) Vibrio and 1 (0.5%) Salmonella were isolated. No Shigella was isolated. Serotyping showed that all the Vibrios were Ogawa serotypes, and the only Salmonella confirmed belong to O group B. All the isolated Vibrio cholerae O1 Ogawa serotypes had similar antibiogram pattern, and were susceptible to ciprofloxacin and tetracycline, but resistant to cotrimoxazole, ampicillin, chloramphenicol and nalidixic acid. The Salmonella O group B was susceptible to ciprofloxacin, tetracycline, co-trimoxazole, chloramphenicol and sulphonamides, but resistant to ampicillin and erythromycin.

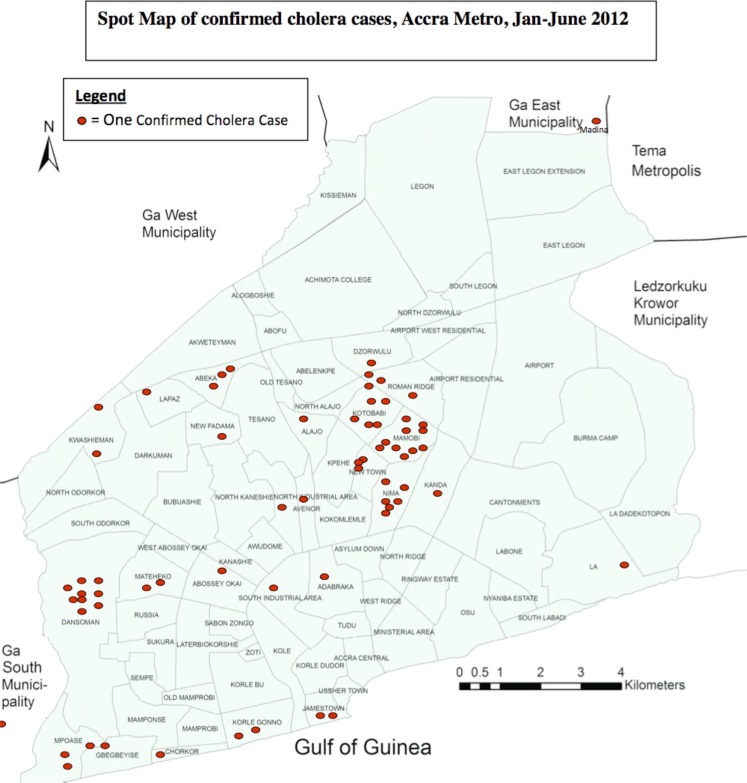

Of the diarrhoeal cases reporting to the Korle-Bu Polyclinic and Maamobi General Hospital, 8.5% and 22.6% resided in Dansoman and Maamobi, respectively. Additionally, most (25.7%) of the confirmed cases were received from these two sub localities of the Accra Metropolis. The only patient with the confirmed salmonella infection, who unfortunately died, resided in Kwashiman.

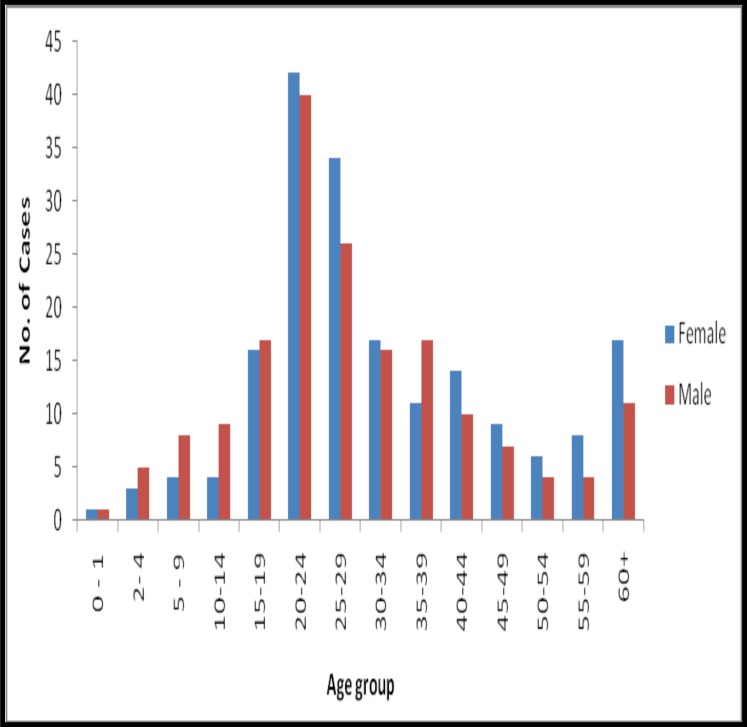

An average of four persons lived in each household of an identified case of diarrhoea. Forty percent of the diarrhoeas occurred among young adults (20–29 years), and 53% of the reported cases were females. Greater than 90% of the recorded diarrhoeal cases presented with vomiting and watery stools. Abdominal pain, fever and nausea were recorded in 49%, 17% and 1% of the patients, respectively. No blood in stool was recorded.

Greater than 78% (283/361) of the reported diarrhoeal cases were hospitalized and treated, whilst 21.6% (78/361) were managed at the outpatient level. Eighty six percent (311/361) of the reported cases indicated having drunk sachet water 24 hours prior to diarrhoea onset. The remainder drank tap water (12.5%) and bottled water (1.4%).

About half (55%) had eaten food bought from street food vendors, while 37.7% and 6.3% had food from home and restaurants respectively.

Discussion

In Ghana and many other countries, national systems exist for disease surveillance, and data generated within these systems are eventually reported to the WHO. Most cases of diarrhoea are however not adequately reported or investigated, and this negatively affects planning and national efforts to combat outbreaks of diarrhoeal disease. Following the 2011 cholera epidemic in Ghana, we investigated every reported diarrhoeal case presenting at the Korle-Bu Polyclinic and the Maamobi General hospital that met our case-definition.

The objective was to generate data that will be useful for the implementation of an enhanced diarrhoeal surveillance system within Accra, which has witnessed several cholera epidemics in the last few years.9

Cholera possess a major public health challenge and an epidemic is declared even if a single case is laboratory confirmed. In an epidemic scenario, however, clinical diagnosis is often used to identify and to manage cases, without the laboratory confirmation of every case.

Typically, under such an epidemic scenario, laboratory investigations are usually used to monitor the epidemic levels, and not necessarily to confirm cases. In this pilot study, after the 2011 major cholera epidemic was declared as being over in December 2011, we confirmed 4 Vibrios in January 2012. Our enhanced surveillance of diarrhoeal diseases in the two selected sites also revealed a sudden upsurge of reported diarrhoeal cases in weeks 12 of 2012. This corresponded with an increased laboratory confirmed cases.

We were thus able to alert prescribers, and this observation corroborated another outbreak of cholera within the Accra Metropolis in 2012. The national CFR of the major 2011 cholera epidemic in Ghana was 1.0%.9 In our pilot study, involving only two sub metros with a duration spanning only six months, the overall CFR was 1.4%. CFR ranging from less than 1% have been reported in Nigeria (781/3000) 15 and Kenya (4/224). 16 Cholera has generally been associated with poor sanitation often associated with displaced populations, and natural disasters.17–19 It however appears that cholera is now endemic in the Accra metropolis, and this calls for an urgent need to strengthen surveillance systems.

In this current study, our laboratory surveillance of diarrhoeal diseases identified only one Salmonella, belonging to O group B serotype. Unfortunately, this patient died 3 days post-admission. Cholera-like diarrhoea, caused by non-Typhoidal Salmonella has recently been reported in Kenya20, further emphasizing the need to scale up laboratory surveillance of diarrhoeal diseases. We speculate that the clinical presentation of our patient who unfortunately died may have mimicked cholera. Earlier nationwide study in Ghana in 2007, identified 4.8% (247/5099) non-typhoidal Salmonella.21 Though it appears the incidence of salmonellosis is declining, the only one identified in the current study resulted in death. This suggests that, though salmonellosis could be rare in a post-cholera epidemic event, serious attention is required to prevent death from salmonellosis. No Shigella was isolated from the rectal culture in the current study. In Ghana22 and elsewhere23, it appears the incidence of shigellosis has considerably decreased over the last few decades.

In the current study, all the Vibrio O1 Ogawa serotypes were susceptible to ciprofloxacin and tetracycline, but were resistant to co-trimoxazole, ampicillin, chloramphenicol and nalidixic acid. We speculate that the same clone of Vibrio may be circulating, and is responsible for the current epidemic. Further analyses using pulsed field gel electrophoresis or multilocus sequence analysis may unravel this hypothesis. Similar antibiotic susceptibilities of Vibrio to ciprofloxacin and tetracycline have been reported elsewhere. 24, 25 In 2007, all but three of Vibrio isolates recovered during an epidemic in Ghana were susceptible to tetracycline but some carried integrons, which are platforms for genetic integration of resistance genes.26

In Ghana, the standard treatment guideline recommends tetracycline as the drug of choice.27 The current findings show that ciprofloxacin and tetracycline are still effective, and can be used in the management of cholera cases.

In the current study, greater than 60% of patients who we investigated reported having consumed sachet water, ate food and drank water from outside home from food vendors before the onset of diarrhoea. We therefore hypothesize that the current epidemic is associated with contaminated foods and water. A case-control study is however needed to confirm this hypothesis. The bacteriological quality of food and water sold by street vendors, including food handling and packaging procedures should be the priority for all. 3, 28

In this pilot study, most of the people that met our case-definition were in their prime age, between 15 and 49 years, raising issues with diarrhoea morbidity. Diarrhoea does not only affects individuals and their families, but puts a large pressure on scares medical supplies.

Limitations

Rectal swabs were not taken for laboratory investigations in patients with diarrhoea reporting during the nights (from 8:00 pm to 7:00 am). Some patients self-medicated with antimicrobials before reporting to the hospital, and therefore, no bacteria grew when cultured.

Conclusions

In an epidemic prone region of cholera, an enhanced surveillance that includes laboratory investigation of all reported diarrhoeal cases can early identify potential emerging outbreaks, and also improve case management at the health facility and community levels. Ciprofloxacin and tetracycline are antimicrobial therapy of choice in the management of cholera in the Accra metropolis.

Figure 2.

Spot Map of confirmed cholera cases reported from the Korle-Bu Polyclinic and Maamobi General Hospital, Accra Metropolis, 1 January to 31 June 2012

Figure 3.

Age group and sex distribution of diarrhoeal cases reporting from Korle-Bu Polyclinic and Maamobi General Hospital, 1 January to 31 June 2012

Acknowledgments

WHO provided funds for this study and we thank Dr. Daniel Kertesz for technical guidance. Our special thanks also go to all the clinical and technical staffs at the Korle-Bu Polyclinic, Maamobi General Hospital, Greater Accra Regional Health Directorate, Accra Metropolitan Health Directorate, Ayawaso and Ablekuma Sub-Metroplitan Health Directorates, the National Public Health and Reference Laboratory and the Department of Microbiology, UGMS for their technical and clinical support. We also express our sincere thanks to Prof. Patience Mensah, Mathew Mikoleit, Drs Eric Mintz and Quick.

The reception, cooperation and support of all health professionals, partners and community members who collaborated to manage the outbreak that emerged are also well appreciated.

References

- 1.Kosek M, Bern C, Guerrant RL. The global burden of diarrhoeal disease, as estimated from studies published between 1992 and 2000. Bull World Health Organ. 2003;81:197–204. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bern C, Martines J, de Zoysa I, Glass RI. The magnitude of the global problem of diarrhoeal disease: a ten-year update. Bull World Health Organ. 1992;70:705–714. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mensah P, Yeboah-Manu D, Owusu-Darko K, Ablordey A. Street foods in Accra, Ghana: how safe are they? Bull World Health Organ. 2002;80:546–554. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mody RK, Meyer S, Trees E, White PL, Nguyen T, Sowadsky R, et al. Outbreak of Salmonella enterica serotype I 4,5,12:i:-infections: the challenges of hypothesis generation and microwave cooking. Epidemiol Infect. 2014;142:1050–1060. doi: 10.1017/S0950268813001787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nabae K, Takahashi M, Wakui T, Kamiya H, Nakashima K, Taniguchi K, Okabe N. A Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O157 outbreak associated with consumption of rice cakes in 2011 in Japan. Epidemiol Infect. 2013;141:1897–1904. doi: 10.1017/S0950268812002439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sousa MA, Mendes EN, Collares GB, Peret-Filho LA, Penna FJ, Magalhaes PP. Shigella in Brazilian children with acute diarrhoea: prevalence, antimicrobial resistance and virulence genes. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2013;108:30–35. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02762013000100005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.IDSR, author. Integrated Disease Surveillance and Respose in the African Region Techical guidelines. http://www.afro.who.int/en/clusters-aprogrammes/dpc/integrated-diseasesurveillance.html. 20101-418.

- 8.Sack DA, Sack RB, Chaignat C. Getting serious about cholera. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:649. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp068144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO. World Health Organization, author. Regional Office for Africa. Outbreak Bull. 2011;1(7):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Opare J, Ohuabunwo C, Afari E, Wurapa F, Sackey S, Der J, Afrakye K, Odei E. Outbreak of cholera in the East Akim Municipality of Ghana following unhygienic practices by small-scale gold miners, November 2010. Ghana Med J. 2012;46:116–123. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Coulombe H. Ghana census-based poverty map: District and sub-district level results. Accra: Ghana Statistical Service; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 12.WHO, author. Manual for the laboratory identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing of bacterial pathogens of public health importance in the developing world. 2003. WHO/CDS/CSR/RMD/ 2003.6.

- 13.Bauer AW, Kirby WM, Sherris JC, Turck M. Antibiotic susceptibility testing by a standardized single disk method. Am J Clin Pathol. 1966;45:493–496. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wikler MA. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing: Eighteenth Informational Supplement. Wayne: Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Adagbada AO, Adesida SA, Nwaokorie FO, Niemogha MT, Coker AO. Cholera epidemiology in Nigeria: an overview. Pan Afr Med J. 2012;12:59. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mahamud AS, Ahmed JA, Nyoka R, Auko E, Kahi V, Ndirangu J, et al. Epidemic cholera in Kakuma Refugee Camp, Kenya, 2009: the importance of sanitation and soap. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2012;6:234–241. doi: 10.3855/jidc.1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ali M, Kim DR, Yunus M, Emch M. Time series analysis of cholera in Matlab, Bangladesh, during 1988–2001. J Health Popul Nutr. 2013;31:11–19. doi: 10.3329/jhpn.v31i1.14744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Patrick A. Cholera in Haiti takes a turn for the worse. Lancet. 2013;381:1264. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(13)60827-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waldman RJ, Mintz ED, Papowitz HE. The cure for cholera--improving access to safe water and sanitation. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:592–594. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1214179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saidi SM, Yamasaki S, Lijima Y, Kariuki S. Cholera-like diarrhoea due to Salmonella infection. J Infect Dev Ctries. 2011;5:68–70. doi: 10.3855/jidc.1168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Newman MJ, Frimpong E, Donkor ES, Opintan JA, Asamoah-Adu A. Resistance to antimicrobial drugs in Ghana. Infect Drug Resist. 2011;4:215–220. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S21769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Opintan J, Newman MJ. Distribution of serogroups and serotypes of multiple drug resistant Shigella isolates. Ghana Med J. 2007;41:8–29. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ranjbar R, Ghazi FM, Farshad S, Giammanco GM, Aleo A, Owlia P, et al. The occurrence of extended-spectrum beta-lactamase producing Shigella spp. in Tehran, Iran. Iran J Microbiol. 2013;5:108–112. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Marin MA, Thompson CC, Freitas FS, Fonseca EL, Aboderin AO, Zailani SB, et al. Cholera outbreaks in Nigeria are associated with multidrug resistant atypical El Tor and non-O1/non-O139 Vibrio cholerae. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7:e2049. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tran HD, Alam M, Trung NV, Kinh NV, Nguyen HH, Pham VC, et al. Multi-drug resistant Vibrio cholerae O1 variant El Tor isolated in northern Vietnam between 2007 and 2010. J Med Microbiol. 2012;61:431–437. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.034744-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Opintan JA, Newman MJ, Nsiah-Poodoh OA, Okeke IN. Vibrio cholerae O1 from Accra, Ghana carrying a class 2 integron and the SXT element. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2008;62:929–933. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkn334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.MOH. Ministry of Health, author. Standard treatment guidelines, Ghana. Sixth edition. 2010. p. 479. Available at: http://apps.who.int/medicinedocs/documents/s180 15en/s18015en.pdf.

- 28.Addo KK, Mensah GI, Bekoe M, Bonsu C, Akyeh ML. Bacteriological quality of sachet water production and sold in Teshie-Nungua suburbs of Accra, Ghana. AJFAND. 2009;9:1019–1030. [Google Scholar]