Abstract

Free gingival grafts have been used in periodontal procedures to augment attached gingiva and cover denuded root surfaces. However, there are few limitations of the same such as esthetic mismatch, mal-alignment of muco-gingival junction formation and bulky appearance. Several modifications have recently been proposed to minimize some of the unfavorable aspects of free gingival grafts. Three cases presenting with Millers Class I/II gingival recession were treated by each different modifications. Satisfactory root coverage and better color match as a compared to free gingival graft was obtained in all the three cases. When indicated these modifications can be advantageous over conventional free gingival grafts in management of Millers Class I/II gingival recession.

Keywords: Free gingival graft, gingival recession, therapeutics

Introduction

Gingival recession is characterized by apical migration of marginal gingiva, which may lead to compromised esthetics, root sensitivity, root caries, and/or pulp hyperemia. Several techniques for the management of gingival recession exist, that is, free grafts (free gingival grafts [FGGs], subepithelial connective tissue graft); pedicled grafts (lateral and coronal), etc.[1] FGGs were initially described by Bjorn, in 1963.[2] The term FGG was first suggested by Nabers.[3] Since then, they have been used not only to cover denuded root surfaces; but also to increase the width and thickness of attached gingiva. The advantages of using an FGG are high predictability and relative ease of technique. However, the conventional FGG has several inherent limitations such as esthetic mismatch and bulky appearance.[4]

Recent modifications of FGG: A case series, recently, several modifications have been proposed to overcome the limitations of FGG. These include partly epithelialized FGG (PE-FGG),[5] gingival unit graft,[6] and epithelialized subepithelial connective tissue graft.[7] Hence, the following manuscript explores the above mentioned recent modifications of FGG as a case series.

Case Reports

Case 1

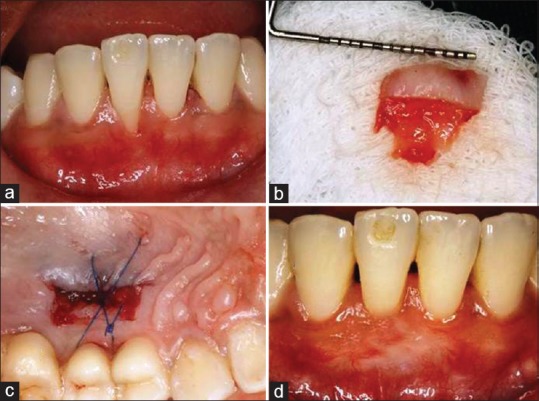

A 21-year-old female reported with a chief complaint of receding gums in the lower anterior tooth. On examination, the patient had a Miller's Class II gingival recession defect in relation to #31 with an attachment loss of 6 mm [Figure 1a]. A minimal amount of attached gingiva was observed on the adjacent teeth. Considering this, the gingival unit graft technique was considered.

Figure 1.

(a) Preoperative view of recession, (b) harvested graft, (c) donor site, (d) 18 postoperative view of recession

Two beveled vertical incisions were given to prepare the recipient bed, which removed the surfaces of interdental papillae and extended apically mesial to the convexities of adjacent teeth, 3–4 mm beyond the mucogingival line. A horizontal incision was given at the level of the mucogingival junction (MGJ).

A split-thickness graft of thickness of approximately 1 mm was obtained from the palate, which extended to the interdental papillae. The graft, thus, obtained was contoured, adapted, and sutured on to the recipient bed [Figure 1b and c]. At 10 days, the healing was uneventful. Partial root coverage was obtained. At 18 months postoperatively, 4 mm recession coverage was observed [Figure 1d].

Case 2

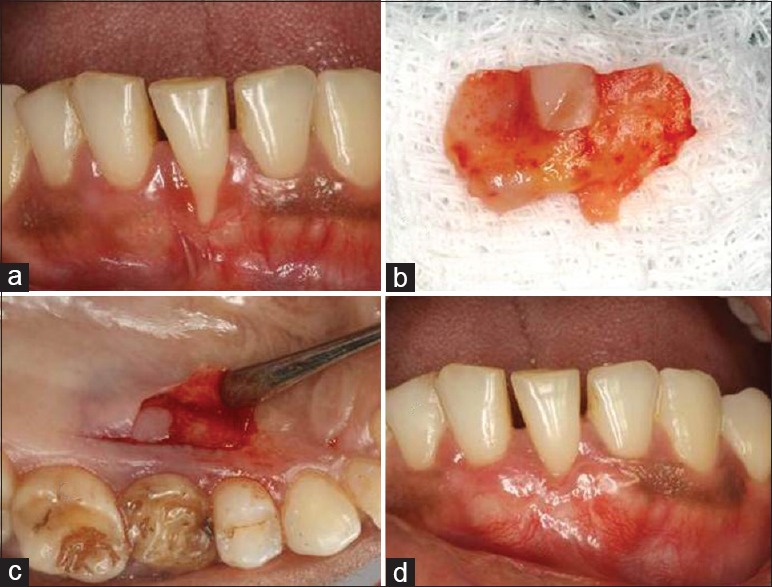

A 29-year-old male patient reported with a chief complaint of sensitivity in the lower anterior tooth. On clinical examination, the patient had a Miller's Class II gingival recession defects in relation to #41 with an attachment loss of 2 mm [Figure 2a]. A minimal amount of attached gingiva was observed on the adjacent teeth. Considering this, a PE-FGG was considered for this patient.

Figure 2.

(a) Preoperative view of recession, (b) harvested graft, (c) donor site, (d) 18 postoperative view of recession

A horizontal partial thickness incision was placed at the MGJ to dissect the alveolar mucosa from the keratinized tissue. The alveolar mucosa was dissected from the underlying periosteum. The keratinized tissue was then de-epithelialized to expose the underlying connective tissue and create a trapezoidal recipient bed.

The graft was harvested from palate extending from the distal aspect of first premolar to the mesial aspect of first molar [Figure 2c]. The dimension of the epithelized portion was calculated from the cemento-enamel junction (CEJ) to MGJ. The rest of the recession was covered with the connective tissue part of the PE-FGG. It was obtained using a modification of the double incision technique as proposed by Bruno.[8] The graft, thus, obtained was contoured, adapted, and sutured on to the recipient bed. The healing was uneventful at 10 days. Complete root coverage was observed at the end of 18 months [Figure 2d].

Case 3

A 33-year-old female patient reported for a routine checkup. On examination, the patient had a Miller's Class II gingival recession defect in relation to #41 with an attachment loss of 3 mm. An minimal amount of attached gingiva was observed on the adjacent teeth and considering this, a PE subepithelial connective tissue graft was considered for this patient.

For the preparation of the recipient bed, a sulcular incision was given on the facial aspect of #41 without extending it above the CEJ. Following this, a supraperiosteal tunnel was prepared facial to #41 extending one tooth mesial and distal to it.

The graft was then harvested from the palate using the dimensions of the recession as a guideline using a modification of the single incision technique proposed by Hürzeler and Weng retaining the small island of the gingival epithelium [Figure 3b and c].[9] The graft, thus, obtained was contoured, adapted, and sutured on to the recipient bed. The healing was uneventful at 10 days postoperatively. Complete root coverage was obtained at the end of 18 months [Figure 3d].

Figure 3.

(a) Preoperative view of recession, (b) harvested graft, (c) donor site, (d) 18 postoperative view of recession

Discussion

Gingival unit graft advocates the use of involving the marginal and papillary part of the gingiva in the FGG in contrast to the conventional submarginal design.[6] The authors argue that the blood supply in the marginal and papillary part of the gingiva is higher than that of the apical gingiva as it contains several interconnecting loops, hairpin networks, anastomoses, and form a dense vascular plexus. This vascular part of gingiva when included in the graft gives superior tissue integration with recipient bed along with a more esthetic coverage and favorable tissue blend. The tissue blend and color match obtained, in our case, were superior to that of conventional FGG. No postoperative recession was noted at the donor site. However, complete root coverage was not obtained. This can be justified by the fact that the preoperative recession depth was large (6 mm), and expecting complete coverage is unrealistic.

In PE-FGG, the apical portion of the graft was de-epithelialized and then graft was placed. This allows the alveolar mucosa to get reallocated spontaneously over the connective tissue part of the graft. Hence, this modification avoids the unesthetic apical displacement of the MGJ that occurs with conventional FGG. In our case, we observed that the technique was easy, effective, esthetically superior, and did limit the relocation of MGJ.

In partly epithelialized-subepithelial connective tissue graft, islands of gingival epithelium corresponding to the dimensions of the recession are retained on top of connective tissue to be used in a tunnel approach.[7] The authors suggest that the gingival epithelium is more resistant to the environment of oral cavity, which protects the underlying connective tissue. The other advantages are no displacement of MGJ and avoidance of vestibule flattening. We found the technique to be effective. However, retaining the epithelium causes increased morbidity as it leaves a small part of the donor site to heal by secondary intention. Furthermore, the procedure is slightly demanding as the epithelial islands should confirm exactly to the size of recession defect.

Proper case selection and careful tissue management are the key to the success of the application of these modifications of FGG. More studies with a larger sample size would give more conclusive evidence so as to effectiveness and applicability of these techniques.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil.

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

References

- 1.Clauser C, Nieri M, Franceschi D, Pagliaro U, Pini-Prato G. Evidence-based mucogingival therapy. Part 2: Ordinary and individual patient data meta-analyses of surgical treatment of recession using complete root coverage as the outcome variable. J Periodontol. 2003;74:741–56. doi: 10.1902/jop.2003.74.5.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bjorn H. Free transplantation of gingiva propria. Sver Tandlakarforb Tidn. 1963;22:684. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nabers JM. Free gingival grafts. Periodontics. 1966;4:243–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen ES. Atlas of Cosmetic and Reconstructive Periodontal Surgery. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Williams and Wilkins; 1994. pp. 65–135. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cortellini P, Tonetti M, Prato GP. The partly epithelialized free gingival graft (pe-fgg) at lower incisors. A pilot study with implications for alignment of the mucogingival junction. J Clin Periodontol. 2012;39:674–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-051X.2012.01896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Allen AL. Use of the gingival unit transfer in soft tissue grafting: Report of three cases. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2004;24:165–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stimmelmayr M, Allen EP, Gernet W, Edelhoff D, Beuer F, Schlee M, et al. Treatment of gingival recession in the anterior mandible using the tunnel technique and a combination epithelialized-subepithelial connective tissue graft-a case series. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2011;31:165–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bruno JF. Connective tissue graft technique assuring wide root coverage. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1994;14:126–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hürzeler MB, Weng D. A single-incision technique to harvest subepithelial connective tissue grafts from the palate. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1999;19:279–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]