Summary

Background

Early social deprivation can negatively affect domains of functioning. We examined psychopathology at age 12 years in a cohort of Romanian children who had been abandoned at birth and placed into institutional care, then assigned either to be placed in foster care or to care as usual.

Methods

We used follow-up data from the Bucharest Early Intervention Project (BEIP), a randomised controlled trial of abandoned children in all six institutions for young children in Bucharest, Romania. In the initial trial, 136 children, enrolled between ages 6–31 months, were randomly assigned to either care as usual or placement in foster care. In this study we followed up these children at age 12 years to assess psychiatric symptoms using the Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children (4th edition; DISC-IV). We also recruited Romanian children who had never been placed in an institution from paediatric clinics and schools in Bucharest as a comparator group who had never been placed in an institution. The primary outcome measure was symptom counts assessed through DISC-IV scores for three domains of psychopathology: internalising symptoms, externalising symptoms, and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). We compared mean DISC-IV scores between trial participants and comparators who had never been placed in an institution, and those assigned to care as usual or foster care. Analyses were done by modified intention to treat. This trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT00747396.

Findings

We followed up 110 children from the BEIP trial between Jan 27, 2011, and April 11, 2014, and 49 children as comparators who had never been placed in an institution. The 110 children who had ever been placed in an institution had higher symptom counts for internalising disorders (mean 0.93 [SD 1.68] vs 0.45 [0.84], difference 0.48 [95% CI 0.14–0.82]; p=0.0127), externalising disorders (2.31 [2.86] vs 0.65 [1.33], difference 1.66 [1.06–2.25]; p<0.0001), and ADHD (4.00 [5.01] vs 0.71 [1.85], difference 3.29 [95% CI 2.39–4.18]; p<0.0001) than did children who had never been placed in an institution. Compared with 55 children randomly assigned to receive care as usual, the 55 children in the foster-care group had fewer externalising symptoms (mean 2.89 [SD 3.00] for care as usual vs 1.73 [2.61] for foster care, difference 1.16 [95% CI 0.11 to 2.22]; p=0.0255), but symptom counts for internalising disorders (mean 1.00 [1.59] for care as usual vs 0.85 [1.78] for foster care, difference 0.15 [−0.35 to 0.65]; p=0.5681) and ADHD (mean 3.76 [4.61] for care as usual vs 4.24 [5.41] for foster care, difference −0.47 [−2.15 to 1.20; p=0.5790) did not differ. In further analyses, symptom scores substantially differed by stability of foster-care placement.

Interpretation

Early foster care slightly reduced the risk of psychopathology in children who had been living in institutions, but long-term stability of foster-care placements is an important predictor of psychopathology in early adolescence.

Funding

National Institute of Mental Health and the John D and Catherine T MacArthur Foundation.

Introduction

Institutional rearing of children is associated with negative long-term sequelae across several domains of functioning (panel 1).4 In particular, heightened rates of psychopathology have been shown years after children are removed from institutional care, including increased internalising disorders, externalising disorders, and attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).5–8 These findings underline that early social deprivation affects several psychiatric domains. Yet, although studies of children after they leave institutions exist, most have had little ability to distinguish between the effects of institutional care and potential selection bias for placement into family care.

Results at the conclusion of the Bucharest Early Intervention Project (BEIP), a randomised controlled trial,1,8 at age 54 months showed that children never exposed to institutional care had significantly fewer symptoms, disorders, and impairments than did children with a history of institutional rearing.8 Children, especially girls, who were randomly assigned to foster care were significantly less likely to meet criteria for an internalising disorder at age 54 months than were children assigned to care as usual; however, no intervention effect was detected for externalising symptoms or disorders, or ADHD symptoms or disorders. This study reassesses psycho pathology in the children at age 11–15 years, roughly 8 years after the formal conclusion of the trial.

The first aim of this study was to assess psycho-pathology in children who had experienced institutional rearing compared with children who had never been placed in an institution. We expected, as with our previous work8 and other research,9–13 that children who had lived in an institution would have greater symptoms of psychopathology. Our second aim was to assess the effectiveness of foster-care intervention on psycho-pathology in early adolescence. Although previous research comparing children who had lived in institutions with children in family placements is limited by selection bias (ie, the children's placements were not randomly determined),14 we predicted reduced psychiatric symptoms in children who were removed from institutions and received foster care compared with those who received care as usual. In particular, we predicted fewer psychiatric disorders and symptoms in children randomly assigned to foster care, with the strongest expected effects on internalising disorders in girls, as we previously noted at 54 months.8 Finally, because some children had experienced changes in foster-care placements, our third aim was to examine the potential association of placement stability with psycho pathology. This assessment was especially relevant because placement changes in foster care have been linked to differences in intelligence quotient (IQ).15 We predicted that in the foster-care group, stable placements would be associated with lower levels of psychopathology than disrupted placement.

Methods

Study design and participants

The original trial was a randomised controlled trial of abandoned children from all six institutions for young children in Bucharest, Romania (age range 6–31 months, mean age 22 months [SD 7.0]). We followed up original trial participants 8 years after the trial ended, when they were aged roughly 12 years. Details about the original sample are available elsewhere.1,8 A third group of Romanian children of similar age who had never been placed in an institution were recruited from paediatric clinics and schools in Bucharest, to act as a typically developing comparison group.15

After approval by the institutional review boards of the three principal investigators (CHZ, NAF, and CAN), and by the local Commissions on Child Protection in Bucharest, the study started in collaboration with the Institute of Maternal and Child Health of the Romanian Ministry of Health. We obtained signed consent from each child's legal guardian as per Romanian law, and written assent from each child for each procedure (unless the child had intellectual disabilities, in which case they gave verbal assent). The children who had never been placed in an institution also gave written assent and their legal guardians (parents) completed signed consents. Studies of vulnerable populations (especially young children raised in institutions) need special ethical consideration, which are discussed in detail elsewhere.16–19

Randomisation and masking

In the original trial,8 after baseline assessment children were randomly assigned to care as usual or foster care by drawing names from a hat. The nature of our study meant that masking of group assignments to children, their carers, or study investigators was not possible. KLH completed the data analysis and was aware of the study variable meanings. In the follow-up assessment in this analysis, diagnostic interviewers were not informed of group assignment.

Procedures

Trial participants received either care as usual1,20 or foster care. Because Bucharest had a shortage of foster care at the outset of the trial, the BEIP investigators created a foster-care network with Romanian col laborators.20,21 The foster parents were supported by social workers in Bucharest who received regular consultation from US clinicians. After advertising and subsequent screening, 56 foster families were selected to care for 68 children. Described more fully elsewhere,21 the foster-care intervention was designed to be affordable, replicable, and grounded in findings from developmental research on enhancing caregiving quality.

We followed up the children when they were approximately 12 years in age and an interviewer administered the structured, computerised Diagnostic Interview Schedule for Children, 4th edition (DISC-IV)22 to each caregiver to ascertain DSM-IV23 diagnostic criteria for ADHD, anorexia nervosa, bipolar disorder, bulimia nervosa, conduct disorder, dysthymia, generalised anxiety disorder, major depressive disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, panic disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, separation anxiety disorder, social phobia, specific phobia, and tic disorder within the past year. The interviewer had not had previous contact with the children and was not informed about group status. DISC probes symptom levels, duration or persistence, age of onset, and functional impairment. It was first translated into Romanian, then back into English, and assessed for meaning at each step by bilingual research staff, although this instrument has not been specifically validated in Romanian populations. For children living with biological parents or foster parents, the mother reported on the child's behaviour. If the mother was not available, fathers provided the report. For children living in institutions, an institutional caregiver who worked with the child regularly and knew them well reported on the child's behaviour. We recorded the number of symptoms and calculated composite scalesfor each disorder within each domain. DISC was administered to caregivers in the laboratory (one time for each child) at the time of the 12-year follow-up.

Outcomes

The primary outcome in the BEIP trial was a range of developmental measures including cognition, physical growth, and psychiatric symptomatology. No pre-specifications of further analyses of psychopathology were made at the time of the initial trial.

In this analysis, we compared psychopathology (as DISC-IV symptom counts for internalising disorders, externalising disorders, and ADHD) between children who had ever been placed in an institution (ie, those who received either care as usual or foster care) versus children who had never been placed in an institution, and between children in care-as-usual versus foster-care groups. We defined internalising disorders as depression and anxiety disorders, and externalising disorders as oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder. ADHD was examined independently, consistent with other studies.24 We assessed these outcomes by group, in each gender by group, and in a further analysis in the foster-care group by children who had stable placements (ie, still with study foster family at follow-up) and children whose placements were disrupted (eg, adopted within Romania, returned to biological family after placement in foster care, placed in government foster care, or later readmitted to institutions because of serious behavioural difficulties at follow-up). For the analysis of placement stability, we examined whether children from the stable versus disrupted groups differed in total psychiatric symptoms, IQ, and percentage of time living in institutional care at age 54 months, when the trial ended.

Statistical analysis

We screened all 187 children younger than 2.5 years who were being raised in institutions in Bucharest, Romania, in February, 2001. We eliminated 51 potential participants because they had genetic syndromes, microcephaly, or obvious signs of fetal alcohol syndrome. The remaining 136 children were randomised. There was no power calculation because we studied all available children.

For the analysis of children who had ever been placed in an institution versus children who had never been placed in an institution, we used intention to treat. For the analysis of psychopathology in care-as-usual versus foster-care groups, we used a modified intention-to-treat analysis including all children randomly assigned to foster care or care as usual who were still in follow-up and who had DISC-IV data available. For the further analysis of the effect of foster-care stability on psychopathology, we assessed children in the foster-care group who were still participating in the trial at follow-up, had DISC-IV data available, and who were still living with their original foster carers at follow-up (if children moved from one study-supported foster-care placement to another, they were treated as disrupted in this study).

We obtained symptom count estimates and disorder prevalence estimates (appendix) for each group, with 95% CIs of group differences, using generalised linear models.25 Symptom counts provide more sensitive measures of psychopathology than do disorder-level analyses, which are reported in the appendix. Generalised linear models provide an alternative to the general linear model that allows for the outcome measures to have non-normal distributions (eg, count data). For disorders, we specified a binary logistic outcome because all disorder-level variables were coded as 0 (no disorder) or 1 (disorder). For symptom-level outcomes, we used a negative binomial regression, which is a type of generalised linear model used to model count data.26 For each analysis, we obtained a Wald χ2 to examine the omnibus group effect, and we used least-significant-difference pairwise comparisons for further analyses to identify significant differences between groups. Mean differences are presented using 95% CI for both differences in occurrences of disorders and mean symptom counts by group.

To address potential issues of non-independence— because for eight pairs of children the same caregiver was interviewed with DISC-IV—one child (chosen at random) was omitted from each pair and all analyses were rerun. We used IBM SPSS statistics version 20 for all our analyses. A data safety monitoring board in Bucharest reviewed the assessments for this follow-up.

This trial is registered with ClinicalTrials.gov, number NCT00747396.

Role of the funding source

The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Results

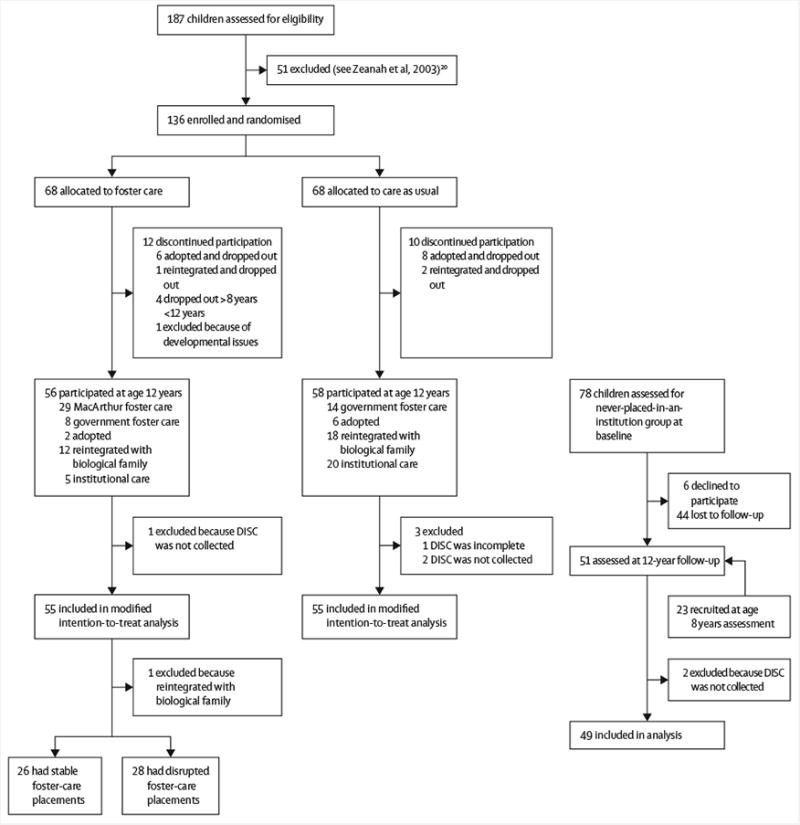

Between Jan 27, 2011, and April 11, 2014, we followed up 110 (81%) of the 136 children in the original randomised trial (55 assigned to foster care and 55 to care as usual; figure 1). Mean age of trial participants at follow-up was 12.95 years (SD 0.68). We also assessed 49 Romanian children recruited from paediatric clinics and schools in Bucharest (21 boys and 28 girls) who had never been placed in an institution. For 11 children who had ever been placed in an institution and 6 children who had never been placed in an institution, the father served as the reporter for DISC. Baseline characteristics for the two randomised groups and the comparator group who had never been placed in an institution are shown in table 1.27 When we followed up the children assigned to foster care, we noted that 26 had stable foster-care placements and 28 had disrupted placements (table 1). One child originally assigned to foster care was excluded from the analysis of foster-care stability because she was reunited with her biological family before placement into foster care. All placement decisions were made by the local commissions for child protection in Romania, thus we do not have information about why disruptions to foster care occurred. Prevalence of psychiatric disorders at follow-up is provided in table 2.

Figure 1. Trial profile.

Three children who were placed in foster care were moved from one placement to another and therefore were placed in the disrupted foster-care group.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of study population.

| Care as usual (n=55) | Foster care (n=55) | Never placed in institution (n=49) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| All foster care (n=55) | Disrupted* (n=28) | Stable (n=26) | |||

| Gender | |||||

| Girls | 26 (47%) | 26 (47%) | 13 (46%) | 12 (46%) | 28 (57%) |

| Boys | 29 (53%) | 29 (53%) | 15 (54%) | 14 (54%) | 21 (43%) |

| Age (years) | 13.03 (0.84) | 12.99 (0.58) | 13.07 (0.61) | 12.90 (0.55) | 12.83 (0.57) |

| Ethnic origin | |||||

| Romanian | 24 (44%) | 33 (60%) | 15 (53%) | 17 (65%) | 47 (96%) |

| Roma | 21 (38%) | 14 (25%) | 8 (29%) | 6 (23%) | 2 (4%) |

| Other/unknown | 10 (18%) | 8 (15%) | 5 (18%) | 3 (12%) | 0 (0%) |

Data are n(%) or mean (SD)

One child excluded because she was reintegrated into her biological family before placement in foster care.

Table 2. Rates of psychiatric disorders by domain.

| Care as usual (n=55) | Disrupted foster care (n=28)* | Stable foster care (n=26) | Ever placed in institution (n=110) | Never placed in institution (n=49) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All children (n=159) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Any psychiatric disorder | 24 (44%) | 12 (43%) | 7 (27%) | 43 (39%) | 8 (16%) |

| Internalising disorders | 8 (15%) | 6 (21%) | 2 (8%) | 16 (15%) | 6 (12%) |

| Externalising disorders | 17 (31%) | 6 (21%) | 4 (15%) | 27 (25%) | 2 (4%) |

| ADHD | 8 (15%) | 8 (29%) | 5 (19%) | 21 (19%) | 1 (2%) |

|

| |||||

| Girls (n=80) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Any psychiatric disorder | 8/26 (31%) | 6/13 (46%) | 3/12 (25%) | 17/52 (33%) | 5/28 (18%) |

| Internalising disorders | 4/26 (15%) | 4/13 (31%) | 2/12 (17%) | 10/52 (19%) | 4/28 (14%) |

| Externalising disorders | 6/26 (23%) | 4/13 (31%) | 0/12 (0%) | 10/52 (19%) | 1/28 (4%) |

| ADHD | 3/26 (12%) | 3/13 (23%) | 1/12 (8%) | 7/52 (14%) | 1/28 (4%) |

|

| |||||

| Boys (n=79) | |||||

|

| |||||

| Any psychiatric disorder | 16/29 (55%) | 6/15 (40%) | 4/14 (29%) | 26/58 (45%) | 3/21 (14%) |

| Internalising disorders | 4/29 (14%) | 2/15 (13%) | 0/14 (0%) | 6/58 (10%) | 2/21 (10%) |

| Externalising disorders | 11/29 (38%) | 2/15 (13%) | 4/14 (29%) | 17/58 (29%) | 1/21 (5%) |

| ADHD | 5/29 (17%) | 4/14 (29%) | 5/15 (33%) | 14/58 (24%) | 0/21 (0%) |

Data are n(%) or n/N(%).

One child excluded because she was reintegrated into her biological family before placement in foster care.

When results from all 110 children who had ever been placed in an institution were compared with those from 49 children who had never been placed in an institution, group status significantly affected all symptom domains (table 3). Children who had ever been placed in an institution had more internalising symptoms (mean DISC-IV score 0.93 [SD 1.68] vs 0.45 [0.84], difference 0.48 [95% CI 0.14–0.82]; p=0.0127), externalising symptoms (2.31 [2.86] vs 0.65 [1.33], difference 1.66 [1.06–2.25]; p<0.0001), and ADHD symptoms (4.00 [5.01] vs 0.71 [1.85], difference 3.29 [2.39–4.18]; p<0.0001) than did children who had never been placed in an institution.

Table 3. Symptom counts by psychopathology domain.

| Ever placed in institution (n=110) | Never placed in institution (n=49) | Difference* (95% CI) | p value* | Care as usual (n=55) | Foster care (n=55) | Difference† (95% CI) | p value† | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All children (n=159) | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Internalising symptoms | 093 (1.68) | 045 (0.84) | 0.48 (0.14–0.82) | 0.0127 | 1.00 (1.59) | 0.85 (1.78) | 0.15 (−0.35 to 0.65) | 0.5681 |

| Externalising symptoms | 2.31 (2.86) | 0.65 (1.33) | 1.66 (1.06–2.25) | <0.0001 | 2.89 (3.00) | 1.73 (2.61) | 1.16 (0.11–2.22) | 0.0255 |

| ADHD | 4.00 (5.01) | 071 (1.85) | 3.29 (2.39–4.18) | <0.0001 | 376 (4.61) | 4.24 (5.41) | −0.47 (−2.15 to 1.20) | 0.5790 |

|

| ||||||||

| Girls (n=80) | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Internalising symptoms | 1.17(2.00) | 0.39 (074) | 0.78 (0.27–1.29) | 0.0066 | 1.12 (1.80) | 1.23 (2.22) | −0.12 (−0.98 to 075) | 0.7944 |

| Externalising symptoms | 1.94 (2.75) | 0.50 (140) | 1.44 (0.72–2.17) | 0.0002 | 2.19 (2.67) | 1.69 (2.85) | 0.50 (0.81–1.81) | 0.4496 |

| ADHD | 3.17 (4.87) | 0.50 (1.90) | 2.67 (1.63–371) | <0.0001 | 3.12 (4.82) | 3.23 (5.02) | −0.12 (−2.09 to 1.86) | 0.9090 |

|

| ||||||||

| Boys (n=79) | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

| Internalising symptoms | 071 (1.31) | 0.52 (0.98) | 0.18 (−0.29–0.66) | 0.4801 | 0.90 (1.40) | 0.52 (1.21) | 0.38 (−0.19 to 0.95) | 0.1874 |

| Externalising symptoms | 2.64 (2.94) | 0.86 (1.24) | 1.78 (0.82–2.74) | 0.0016 | 3.52 (3.19) | 1.76 (2.42) | 1.76 (0.10–3.42) | 0.0271 |

| ADHD | 474 (5.05) | 1.00 (1.79) | 374 (2.27–5.21) | <0.0001 | 4.34 (4.42) | 5.14 (5.67) | −0.79 (−3.49–1.90) | 0.5620 |

Data are mean (SD).

Ever placed in institution vs never placed in institution.

Care as usual vs foster care.

When girls and boys were analysed separately, girls (n=52) who had ever been placed in an institution had significantly more internalising symptoms than did girls (n=28) who had never lived in an institution (p=0.0006). However, group status did not affect internalising symptoms for boys (p=0.4801). Both girls and boys who had ever been placed in an institution had significantly more externalising symptoms than did those who had never been placed in an institution (p=0.0002 for girls; p=0.0016 for boys). Similarly, both girls and boys who had ever been placed in an institution had significantly more ADHD symptoms than did those who had never lived in an institution (p<0.0001 for both). Internalising symptoms did not differ between the care-as-usual and foster-care groups (mean DISC-IV score 1.00 [SD 1.59] vs 0.85 [1.78], difference 0.15 [95% CI -0.35 to 0.65], p=0.5681; table 3). Analyses for girls and boys separately showed no effect of randomised group on internalising symptoms (p=0.7944 for girls and p=0.1874 for boys; table 3). Children in the care-as-usual group had significantly more externalising symptoms than did children in the foster-care group (mean DISC-IV score 2.89 [SD 3.00] vs 1.73 [2.61], difference 1.16 [95% CI 0.11 to 2.22], p=0.0255). Among girls, group status did not affect counts of externalising symptoms; however, group status significantly affected externalising symptom count in boys (p=0.0271). ADHD symptoms did not differ between the care-as-usual and foster-care groups (p=0.5790). We noted no differences between groups even after ADHD results were analysed separately for girls and boys.

In a further analysis, we divided children who were randomly assigned to foster care into those with stable foster care and those with disrupted foster care. Children in stable placements did not significantly differ from those in disrupted placements for total psychiatric symptoms assessed at age 54 months (mean 9.17 [SD 20.36] for stable foster care vs 13.19 [10.04] for disrupted foster care, difference 4.01 [95% CI–9.32 to 1.30]), full-scale IQ at age 54 months (mean 82.83 [20.22] for stable foster care vs 80.48 [17.69] for disrupted foster care, difference 2.35 [−8.43 to 13.12]), or percentage of time spent living in institutions through age 54 months (36% for stable foster care vs 37% for disrupted foster care, difference–0.22 [95% CI–7.60 to 7.16]; appendix).

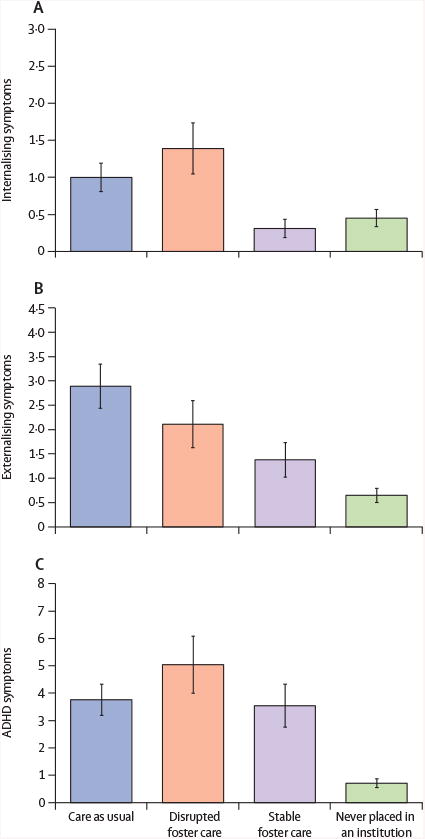

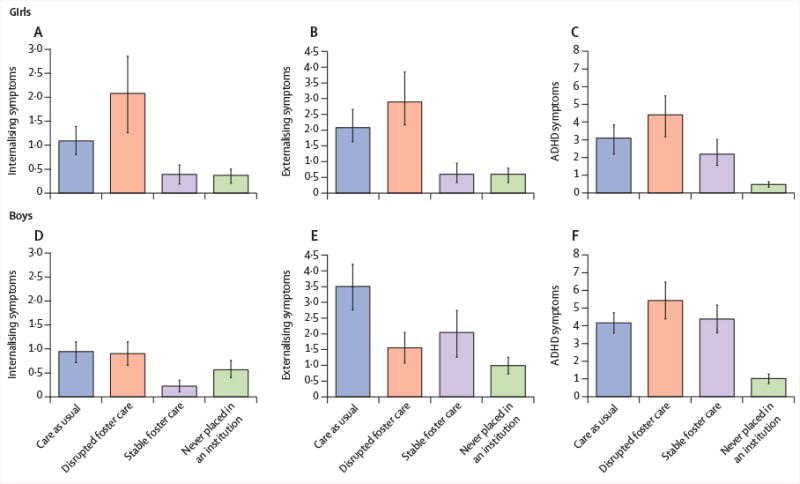

We repeated the analysis of psychopathology as assessed by mean DISC-IV scores using the new foster-care groups of stable and disrupted placements. Figure 2 shows symptom counts by psychopathology domain, and figure 3 shows symptom counts by psychopathology domain and gender, using the new groupings. The full list of mean DISC-IV scores, differences with 95% CIs for pairwise comparisons, and p values of all comparisons are provided in the appendix.

Figure 2. Symptom counts from each psychopathology domain by institutional care history and stability of foster care.

Symptoms are for internalising, externalising, and ADHD. ADHD=attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Figure 3. Symptom counts from each psychopathology domain by institutional care history and stability of foster care, stratified by gender.

Symptom counts split by girls and boys for internalising, externalising, and ADHD. ADHD=attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Children in the care-as-usual group and disrupted foster-care groups had more internalising symptoms than children in the stable foster-care group and the group of children who had never been placed in an institution. This effect was also shown for girls (overall effect of group status among girls on internalising symptoms, p=0.0026; figure 3). The difference for internalising symptoms for girls in care as usual versus stable foster care was not significant. Among boys, the overall effect of group for internalising symptoms was also not significant (p=0.1711; figure 3).

For externalising symptoms, we noted a stepwise effect with symptoms decreasing across the care-as-usual group, followed by disrupted foster care, stable foster care, and never been placed in an institution (figure 2), with a significant effect of group status (p<0.0001). Group status also significantly affected externalising symptoms for girls (p<0.0001) and boys (p=0.0019; figure 3) separately. Girls in the care-as-usual and disrupted foster-care groups had significantly more externalising symptoms than those in the stable foster-care group or in the group who had never been placed in an institution; for boys, care as usual was associated with more externalising symptoms than disrupted foster care or no institutionalisation, but no differences were noted in externalising symptoms for boys in the stable foster-care group versus disrupted foster care.

Similarly, group status significantly affected ADHD symptom count (p<0.0001). Children in the care-as-usual, disrupted foster-care, and stable foster-care groups had more ADHD symptoms than did those in the never-institutionalised group. Among both girls and boys, we noted a significant group effect for ADHD symptoms (p<0.0001 for girls; p<0.0001 for boys; figure 3). The pattern of ADHD symptom count for both genders was similar to the distribution for all children.

To address potential issues of non-independence, all analyses were rerun omitting one child from each pair (chosen at random). The results obtained from the reduced sample (data not shown) showed the same pattern of significant group differences as those obtained with the full sample.

Discussion

In this 8-year follow-up after the end of a randomised controlled trial, we examined psychiatric symptoms and disorders in Romanian children placed in institutional care who were assigned to foster care or care as usual, and in children who had never been placed in an institution. In our cohort, we noted that a history of institutional rearing was associated with higher levels of psychiatric morbidity, internalising psychopathology, externalising psychopathology, and ADHD at 12 years of age compared with a cohort of typically developing children who had never been placed in an institution. These data are similar to our findings from the trial sample when assessed at age 54 months.8

Using a conservative modified intention-to-treat approach, the foster-care intervention had few effects, restricted to fewer externalising symptoms in children randomly assigned to foster care, and were accounted for by fewer externalising symptoms in boys in the foster-care group than boys in the care-as-usual group (panel 2). Symptom counts were more sensitive to group differences than were disorder-level analyses (appendix), probably because of differences in power from these two methodological approaches.36 Increased behavioural difficulties have been noted in late childhood and early adolescence in other samples of children who had been previously placed in an institution.10,37 The finding of reduced externalising symptoms in our main analysis might represent a sleeper effect of the role of early foster-care intervention, or perhaps show that time in foster care might help to reduce the long-term effect of institutional care on externalising symptoms. Because placement was not an important predictor of externalising psycho pathology in boys, more weight might be attributed to the sleeper-effect hypothesis, because even boys who were in foster care for only a short time because of placement disruption showed reduced levels of externalising psychopathology. However, disrupted foster care was similar to care as usual across other psychopathological domains and for girls.

Our findings here contrast with the results of the trial at 54 months,8 in which an intervention effect was shown for girls in internalising disorders, but at 12 years, no effect was noted in internalising disorders for girls or boys. Although no group differences were apparent at this timepoint for internalising disorders, reductions were noted in internalising disorders for children with a history of institutional care. At 54 months, 44% of the care-as-usual group and 22% of the foster-care group had internalising disorders, whereas at age 12, 15% of both groups had an internalising disorder (appendix). Thus, internalising symptoms seem to be reduced across all groups by age 12 years.

The children in our sample experienced many disruptions between age 4 and 12 years (figure 1). When we undertook analyses using stable and disrupted foster care as separate groups, we noted important differences in psychopathology at age 12 years in children who had experienced early psychosocial deprivation but remained in stable, high-quality foster care following initial placement into the study compared with children whose placments into foster care were disrupted. We are mindful of the drawbacks of breaking the intention-to-treat statistical plan; in doing so, we risked potential sample bias. However, without this further analysis, we were unable to examine the intervention effects directly because we could not distinguish the outcomes resulting from the intervention versus those resulting from other factors. Additionally, this approach might provide a more realistic perspective on child outcomes after foster-care interventions in view of the high levels of placement disruption experienced by children in foster care. One possibility—that children no longer in their foster-care placement might differ from those who remained in their placement—was examined to establish whether child characteristics could predict disruptions. Our analyses showed no evidence to support this explanation, because the children whose placements were disrupted were similar to those whose placements remained stable for institutional-care history, IQ, and total psychiatric symptoms at age 54 months. Thus, our results are at least compatible with the notion that disruptions lead to psychopathology, rather than the other way around.

Clear policy implications exist for studying the effect of the stability of placements on the long-term outcomes of family-placement interventions after institutional rearing. These could be done in conjunction with other research documenting the harmful effect of placement disruptions in foster care,38 and could lend support to the belief that stable placements are crucial for positive child development. Our approach to following the placement paths of children after initial foster-care placements might better track real-life outcomes of young people with a history of institutional care who obtain foster placements. Externalising symptoms were affected by the instability of the foster-care placement. Symptoms for children with stable placements did not significantly differ from those for children who had never been placed in an institution, but both groups had significantly lower levels of externalising symptoms than children whose placements were disrupted, or those from the care-as-usual group. For internalising symptoms, stability of the foster-care placement was especially important, such that children who remained in their foster-care placement had significantly lower levels of internalising symptoms than children from the foster-care group who were no longer in their original placements, and children from the care-as-usual group. In fact, children displaced from their foster-care placement had similar amounts of internalising symptoms as did those in the care-as-usual group, emphasising the adverse effects of placement disruptions on vulnerable children.

By contrast with the externalising and internalising domains, for which the effects of placement stability were related to lower levels of psychopathology, ADHD was unrelated to placement stability. The persisting rise of ADHD for both boys and girls across all groups who had ever been placed in an institution is similar to results from other research5 that shows increased inattention and hyperactivity symptoms after institutional rearing, and also the persistence of these symptoms even after adoption. Other studies of young people who have lived in institutions,23,27 however, have shown reduced ADHD symptoms with earlier age of family placement than occurred in our study.

Gender was an important moderator of psycho-pathology in this study, because girls who were still in their original foster-care placement showed significantly fewer externalising and internalising psychiatric symptoms than did those in the care-as-usual group, and similar psychiatric symptoms as children in the group who had never been placed in an institution. These findings are similar to our previous results8 of girls showing significantly fewer internalising symptoms at 54 months, yet our analyses needed to break the intention-to-treat statistical plan to show this effect. Girls in the foster-care group who had one or more significant placement disruption had prevalence of externalising and internalising symptoms similar to children in the care-as-usual groups. This result is consistent with other evidence that girls might be more susceptible to adversity experienced in adolescence.39 For boys, the stability of the foster-care placement was not associated with fewer externalising symptoms, suggesting that, for this domain in boys, being placed in foster care mattered more than how stable the placement was. However, boys in stable foster-care placements had fewer internalising symptoms than children in the care-as-usual group or those who experienced disruptions to their foster care.

Our study had several limitations, including the use of only caregiver reports to establish psychopathology; however, a substantial number of children had sufficiently low IQs that the data obtained regarding their own symptom reports were unreliable. Additionally, because this study consists of a follow-up to a randomised trial, we were limited by the number of available participants within each group, thus the power to detect differences in the planned analyses was low. Although many of the group comparisons were significantly different, the wide CIs suggest that uncertainty remains about the precision of effect sizes. An additional limitation relates to the potential role of disruptions within the care-as-usual group, because all children in this group had experienced placement disruptions by age 12 years: at this age, about one-third were in institutional care (although all changed institutions at least once), one-third were in non-related family-care placements, and one-third were reintegrated with their biological families.

In conclusion, stable, high-quality foster care emerged as an important predictor of reduced psychopathology in early adolescence for children who had experienced severe deprivation in their early life. Although ADHD was impervious to foster-care inter vention and placement stability, internalising and externalising psycho pathological symptoms were fewer in children who remained with their original foster families. In our modified intention-to-treat analysis, the effects were slight; however, several reasons exist why a randomised trial done in early childhood might produce findings that attenuate over time, including the effects of subsequent life events after the initial foster-care placement. Thus, this study provides support for policies promoting early intervention for children living in institutions, and emphasises the need for maintaining high-quality foster-care placements across childhood and into early adolescence.

Panel 1. Background of the Bucharest Early Intervention Project.

The Bucharest Early Intervention Project (BEIP) was the first randomised controlled trial comparing foster care with institutional care in young children. The project began in April, 2001, when government-sponsored foster care was largely unavailable in Romania. BEIP began with 136 children who were abandoned at or soon after birth and placed in institutions in Bucharest, Romania, and included assessments of growth, cognitive, social, and emotional development, and brain functioning at baseline (age 6–31 months). Assessments were done at ages 30, 42, and 54 months, and at 8 and 12 years. Groups studied were those randomly assigned to removal from institutional care and placement in high-quality, project-sponsored foster care, and those randomly assigned to care as usual. A third control group of family-reared children was recruited from paediatric clinics and schools in Bucharest for comparison. When the study was completed at 54 months, the management and support of the foster-care network was passed to local child-protection authorities in Bucharest. The children were formally reassessed in follow-ups done when children were aged 8 and 12 years.

The findings from this trial were that children with histories of abandonment and institutional rearing had significantly compromised development in almost every domain examined compared with family-reared children who had never been placed in an institution.1 Children who were randomly assigned to foster care made gains in most domains compared with children who received care as usual, although rarely did developmental outcomes become similar to those for children who had never been placed in an institution. Children placed in foster care at younger ages showed more gains in some domains, eg, language development2 and attachment status,3 compared with those placed in foster care at older ages. Follow-up data continue to be studied, including examining the degree to which gains due to the foster-care intervention have persisted.

Panel 2. Research in context.

Systematic review

At the time the original randomised trial was planned (planning took place over 18 months in 1999 and 2000, and piloting of the study occurred from December, 2000, to March, 2001), a systematic literature review showed that no randomised controlled trials of foster care for children living in institutions had ever been undertaken. To our knowledge, the Bucharest Early Intervention Project remains the only such randomised trial. On Jan 26, 2015, we systematically reviewed the literature in Google Scholar and PubMed to locate all studies of intervention after institutional care that examined psychopathological symptoms with the following search terms: “orphanage”, “institutional care”, “psychopathology”, “disorders”, “internalising”, “externalising”, “ADHD”, “attention”, “foster care”, and “family care” with no date restrictions. We selected nine studies that examined children in institutional care versus those in foster care or family-based living placements for review, although none were randomised controlled trials. The absence of randomised trials restricted any inferences we could draw because of issues related to potential selection bias of children to family-based placements. Although some studies suggested no differences in internalising domains on the basis of placement form,28,29 most studies suggested greater internalising difficulties in children in institutional care.30–34 All studies that examined externalising psychopathological symptoms showed more difficulties in those children in institutional care compared with children in foster care,30–33 and one study showed only greater behavioural difficulties in girls in institutional care compared with girls in families.29 Only one study examined inattention, and showed that boys placed in residential care had more symptoms than boys in foster care.35

Interpretation

The results from our trial provide a more accurate characterisation of the effects of foster-care placement for young children in institutions than has been available previously. Because of the randomised design, any differences in children randomly assigned to foster care compared with children who received care as usual should be due to the intervention. Although in previous studies, children in foster care or in families had fewer psychopathological symptoms than children in institutions, the findings from our main analysis suggest small long-term reductions in symptoms for children placed in foster care. Our further examination of foster-care outcomes by placement status underscores the importance of stability of high-quality, foster-care placements. The clinical implications of this study add to findings that children are at heightened risk of harm by placement disruptions. From a policy perspective, maintenance of the stability of high-quality foster care for vulnerable children should be prioritised. Whenever possible, children who have disruptions could merit further clinical attention to manage the transition in placements. Furthermore, policy implications from these and other related findings should emphasise the importance of placing children with families rather than in institutions. Foster care should be both high quality and stable over time, with concerted efforts to reduce placement disruptions, because these factors might buffer children who have experienced serious early adversity from subsequent psychiatric disorders.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by the National Institute of Mental Health (MH091363) and the John D and Catherine T MacArthur Foundation to NAF, CAN, and CHZ.

Footnotes

Contributors: KLH and CHZ did the literature search. KLH constructed the figures. CAN, NAF, and CHZ designed the study. CAN, NAF, and CHZ supervised the data collection. KLH did the data analysis. KLH, MMG, SSD, DM, CAN, NAF, and CHZ interpreted the data. KLH, MMG, SSD, DM, CAN, NAF, and CHZ wrote the manuscript.

Declaration of interests: We declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Kathryn L Humphreys, Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans, LA, USA.

Mary Margaret Gleason, Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans, LA, USA.

Stacy S Drury, Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans, LA, USA.

Devi Miron, Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans, LA, USA.

Prof Charles A Nelson, 3rd, Boston Children's Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA; Harvard Graduate School of Education, Cambridge, MA, USA.

Prof Nathan A Fox, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, USA.

Prof Charles H Zeanah, Tulane University School of Medicine, New Orleans, LA, USA.

References

- 1.Nelson CA, Fox NA, Zeanah CH. Romania's abandoned children. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Windsor J, Benigno JP, Wing CA, et al. Effect of foster care on young children's language learning. Child Dev. 2011;82:1040–46. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01604.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smyke AT, Zeanah CH, Fox NA, Nelson CA, Guthrie D. Placement in foster care enhances quality of attachment among young institutionalized children. Child Dev. 2010;81:212–23. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2009.01390.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tottenham N. The importance of early experiences for neuro-affective development. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 2014;16:109–29. doi: 10.1007/7854_2013_254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rutter M, Sonuga-Barke EJ, Beckett C, et al. Deprivation-specific psychological patterns: effects of institutional deprivation by the English and Romanian adoptee study team. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 2010;75:1–252. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stevens SE, Sonuga-Barke EJS, Kreppner JM, et al. Inattention/overactivity following early severe institutional deprivation: presentation and associations in early adolescence. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2008;36:385–98. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9185-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tottenham N, Hare TA, Quinn BT, et al. Prolonged institutional rearing is associated with atypically large amygdala volume and difficulties in emotion regulation. Dev Sci. 2010;13:46–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7687.2009.00852.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zeanah CH, Egger HL, Smyke AT, et al. Institutional rearing and psychiatric disorders in Romanian preschool children. Am J Psychiatry. 2009;166:777–85. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.08091438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Colvert E, Rutter M, Beckett C, et al. Emotional difficulties in early adolescence following severe early deprivation: findings from the English and Romanian adoptees study. Dev Psychopathol. 2008;20:547–67. doi: 10.1017/S0954579408000278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wiik KL, Loman MM, Van Ryzin MJ, et al. Behavioral and emotional symptoms of post-institutionalized children in middle childhood. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;52:56–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02294.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tieman W, van der Ende J, Verhulst FC. Psychiatric disorders in young adult intercountry adoptees: an epidemiological study. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:592–98. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.3.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ellis BH, Fisher PA, Zaharie S. Predictors of disruptive behavior, developmental delays, anxiety, and affective symptomatology among institutionally reared Romanian children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43:1283–92. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000136562.24085.160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beverly BL, McGuinness TM, Blanton DJ. Communication and academic challenges in early adolescence for children who have been adopted from the former Soviet Union. Lang Speech Hear Serv Sch. 2008;39:303–13. doi: 10.1044/0161-1461(2008/029). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zeanah CH, Smyke AT, Settles L. Children in orphanages. In: McCartney K, Phillips D, editors. Blackwell handbook of early childhood development. Malden: Blackwell Publishing; 2006. pp. 224–54. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fox NA, Almas AN, Degnan KA, Nelson CA, Zeanah CH. The effects of severe psychosocial deprivation and foster care intervention on cognitive development at 8 years of age: findings from the Bucharest early intervention project. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2011;52:919–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02355.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Millum J, Emanuel EJ. Ethics. The ethics of international research with abandoned children. Science. 2007;318:1874–75. doi: 10.1126/science.1153822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nelson CA, Zeanah CH, Fox NA, Marshall PJ, Smyke AT, Guthrie D. Cognitive recovery in socially deprived young children: the Bucharest early intervention project. Science. 2007;318:1937–40. doi: 10.1126/science.1143921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wassenaar DR, Zeanah CH, Koga SF, et al. Commentary: ethical considerations in international research collaboration: the Bucharest early intervention project. Infant Ment Health J. 2006;27:577–80. doi: 10.1002/imhj.20108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zeanah CH, Fox NA, Nelson CA. The Bucharest early intervention project: case study in the ethics of mental health research. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2012;200:243–47. doi: 10.1097/NMD.0b013e318247d275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zeanah CH, Nelson CA, Fox NA, et al. Designing research to study the effects of institutionalization on brain and behavioral development: the Bucharest early intervention project. Dev Psychopathol. 2003;15:885–907. doi: 10.1017/s0954579403000452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smyke AT, Zeanah CH, Fox NA, Nelson CA. A new model of foster care for young children: the Bucharest early intervention project. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2009;18:721–34. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shaffer D, Fisher P, Lucas CP, Dulcan MK, Schwab-Stone ME. NIMH diagnostic interview schedule for children vIV (NIMH DISC-IV): description, differences from previous versions, and reliability of some common diagnoses. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:28–38. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.American Psychiatric Association. DSM-IV. text revision. Washington: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tibu F, Humphreys KL, Fox NA, Nelson CA, Zeanah CH. Psychopathology in young children in two types of foster care following institutional rearing. Infant Ment Health J. 2014;35:123–31. doi: 10.1002/imhj.21428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nelder JA, Wedderburn RWM. Generalized linear models. J R Stat Soc Ser A. 1972;135:370–84. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gardner W, Mulvey EP, Shaw EC. Regression analyses of counts and rates: Poisson, overdispersed Poisson, and negative binomial models. Psychol Bull. 1995;118:392–404. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.118.3.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smyke AT, Koga SF, Johnson DE, et al. The caregiving context in institution-reared and family-reared infants and toddlers in Romania. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2007;48:210–18. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2006.01694.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hasanović M, Sinanović O, Selimbasić Z, Pajević I, Avdibegović E. Psychological disturbances of war-traumatized children from different foster and family settings in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Croat Med J. 2006;47:85–94. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lassi ZS, Mahmud S, Syed EU, Janjua NZ. Behavioral problems among children living in orphanage facilities of Karachi, Pakistan: comparison of children in an SOS village with those in conventional orphanages. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2011;46:787–96. doi: 10.1007/s00127-010-0248-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ahmad A, Mohamad K. The socioemotional development of orphans in orphanages and traditional foster care in Iraqi Kurdistan. Child Abus Negl. 1996;20:1161–73. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(96)00067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahmad A, Qahar J, Siddiq A, et al. A 2-year follow-up of orphans' competence, socioemotional problems and post-traumatic stress symptoms in traditional foster care and orphanages in Iraqi Kurdistan. Child Care Health Dev. 2005;31:203–15. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2004.00477.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee RM, Seol KO, Sung M, Miller MJ. The behavioral development of Korean children in institutional care and international adoptive families. Dev Psychol. 2010;46:468–78. doi: 10.1037/a0017358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kang H, Chung IJ, Chun J, Nho CR, Woo S. The outcomes of foster care in South Korea ten years after its foundation: a comparison with institutional care. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2014;39:135–43. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Whetten K, Ostermann J, Whetten RA, et al. A comparison of the wellbeing of orphans and abandoned children ages 6–12 in institutional and community-based care settings in five less wealthy nations. PLoS One. 2009;4:e8169. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0008169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Roy P, Rutter M, Pickles A. Institutional care: associations between overactivity and lack of selectivity in social relationships. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2004;45:866–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kraemer HC, Noda A, O'Hara R. Categorical versus dimensional approaches to diagnosis: methodological challenges. J Psychiatr Res. 2004;38:17–25. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3956(03)00097-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sonuga-Barke EJ, Schlotz W, Kreppner J. Differentiating developmental trajectories for conduct, emotion, and peer problems following early deprivation. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 2010;75:102–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-5834.2010.00552.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Newton RR, Litrownik AJ, Landsverk JA. Children and youth in foster care: disentangling the relationship between problem behaviors and number of placements. Child Abus Negl. 2000;24:1363–74. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(00)00189-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hankin BL, Abramson LY. Development of gender differences in depression: an elaborated cognitive vulnerability-transactional stress theory. Psychol Bull. 2001;127:773–96. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.127.6.773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]