Abstract

We report a simple, effective method to assess the cytosolic delivery efficiency and kinetics of cell-penetrating peptides using a pH-sensitive fluorescent probe, naphthofluorescein.

Cell-penetrating peptides (CPPs) are short, cationic and/or amphipathic peptides which are capable of transporting a wide variety of cargo molecules across the eukaryotic cell membrane.1 Since the initial discovery of the Tat peptide (YGRKKRRQRRR) from HIV trans-activator of transcription,2 numerous other CPPs have been reported, deriving from both naturally-occurring proteins and “rational” design efforts.1 Although the mechanism of cellular uptake of CPPs remains a subject of debate and likely varies with the CPP sequence, the nature of cargo molecules, and the test conditions (e.g., CPP concentration), there is a growing consensus that at lower concentrations (<10 µM), cationic CPPs [e.g., Tat and nonaarginine (R9)] enter cells primarily through endocytic mechanisms.3 It is also recognized that most of these CPPs are inefficient in exiting the endosome (i.e., they are entrapped in the endosome), resulting in low cytosolic delivery efficiencies.4 For instance, mammalian cells treated with fluorescently labelled Tat and R9 peptides generally exhibit punctate fluorescence patterns when examined by confocal microscopy, consistent with predominantly endosomal localization of the CPPs (vide infra). Therefore, methods that can distinguish the endosomal and cytosolic CPP populations are highly desirable and necessary in order to accurately determine the cytosolic delivery efficiency of CPPs.

The most commonly used method to quantitate the cellular uptake of CPPs has involved covalent labelling of the CPPs with a fluorescent dye [e.g., fluorescein (FL) or rhodamine (Rho)] and fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS). This method measures the total amount of internalized CPPs but does not differentiate the fluorescence derived from endosomally entrapped CPPs from that of cytosolic (and nuclear) CPPs. To overcome the above limitation, previous investigators have devised several innovative methods to more accurately determine the cytosolic CPP concentrations.5–8 Langel and others attached a disulphide-linked fluorescence donor-quencher pair to CPPs; upon entry into the cytoplasm, the disulphide bond is cleaved to release the quencher, resulting in an increase in the fluorescence yield of the donor.5 Wender et al. expressed a luciferase enzyme in the cytoplasm of mammalian cells, which generates a luminescence signal when luciferin is transported into the cytoplasm by CPPs.6 Kodadek and Schepartz conjugated CPPs to dexamethasone and assessed the cytosolic access of CPPs by quantifying dexamethasone-induced expression or nuclear translocation of a green fluorescent protein.7 We previously employed phosphocoumaryl aminopropionic acid (pCAP) as a reporter for cytosolic and nuclear CPP concentrations.8 pCAP is non-fluorescent, but is rapidly dephosphorylated by endogenous protein tyrosine phosphatases (which are only found in the cytoplasm and nucleus of mammalian cells) to generate a fluorescent product. In this work, we sought to develop an operationally simple method to monitor the endosomal release of CPPs and determine their cytosolic delivery efficiencies by using standard analytical instruments without the need for any complex probe preparation. We took advantage of the acidic environment inside the endosomes and employed a pH-sensitive fluorophore, naphthofluorescein9 (NF, Fig. 1), as the reporter. With a pKa of ~7.8, NF is expected to be nearly completely protonated and non-fluorescent (when excited at ≥590 nm) inside the acidic endosomes, which have pH values of ≤6.0.10 However, once an NF-labelled CPP escapes from the endosome into the cytosol, which typically has a pH of 7.4, it should result in a large increase in fluorescence intensity, which can be conveniently monitored by FACS or live-cell confocal microscopy.

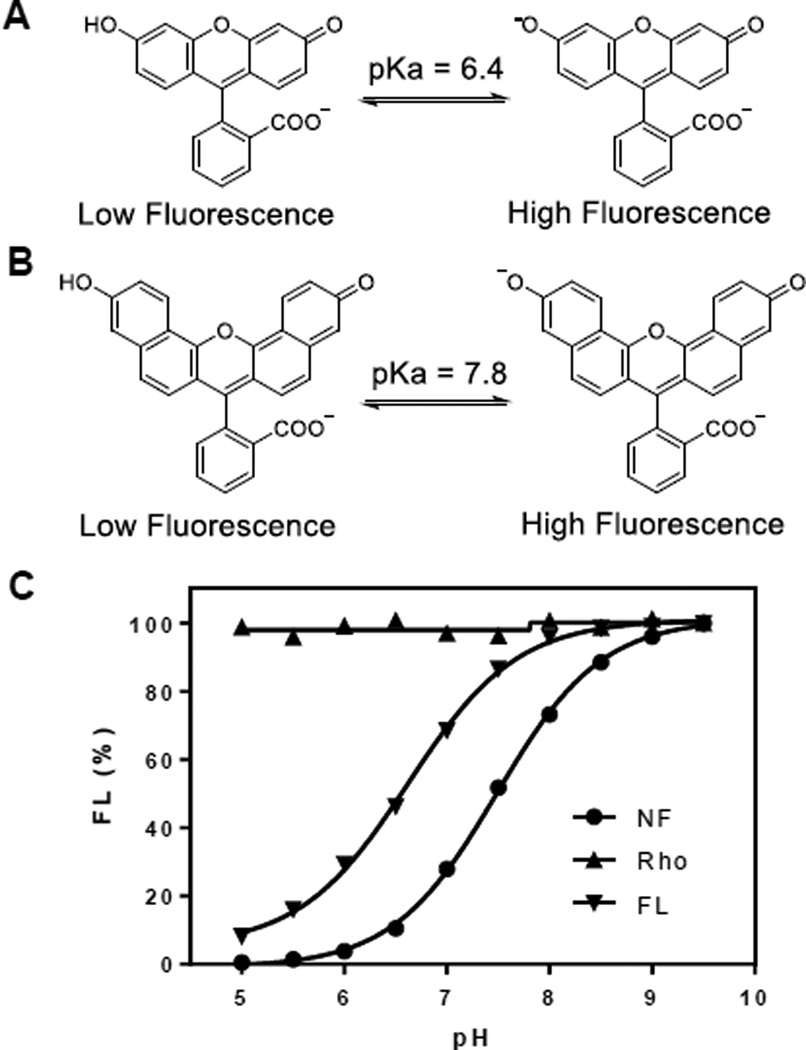

Fig. 1.

Effect of pH on the fluorescence intensity of FL, NF, and Rho. (A and B) Structures of FL and NF before and after deprotonation. (C) Plot of the fluorescence intensity of FL (Ex/Em = 485/525 nm), NF (Ex/Em = 595/660 nm), and Rho (Ex/Em = 545/590 nm) as a function of pH. All values reported are relative to those at pH 9.5 (100%).

We first compared the pH sensitivity of FL, NF, and Rho. As expected, Rho exhibited no significant change in fluorescence intensity over the pH range of 5–10, whereas FL and NF were highly sensitive to pH, showing pKa values of 6.6 and 7.5, respectively (Fig. 1). At pH 6.0, FL retained ~30% of its maximum fluorescence, while NF had minimal fluorescence (3.8% of its maximum). We also attached the three dyes to the glutamine side chain of a cyclic CPP, cyclo(FΦRRRRQ)8 (Fig. S1 and Table S1; cFΦR4, where Φ is L-2-naphthylalanine) and repeated the pH titration experiments. The resulting CPP-dye adducts, cFΦR4FL, cFΦR4NF, and cFΦR4Rho, showed essentially identical pH profiles to the unmodified FL, NF, and Rho, respectively (Fig. S2).

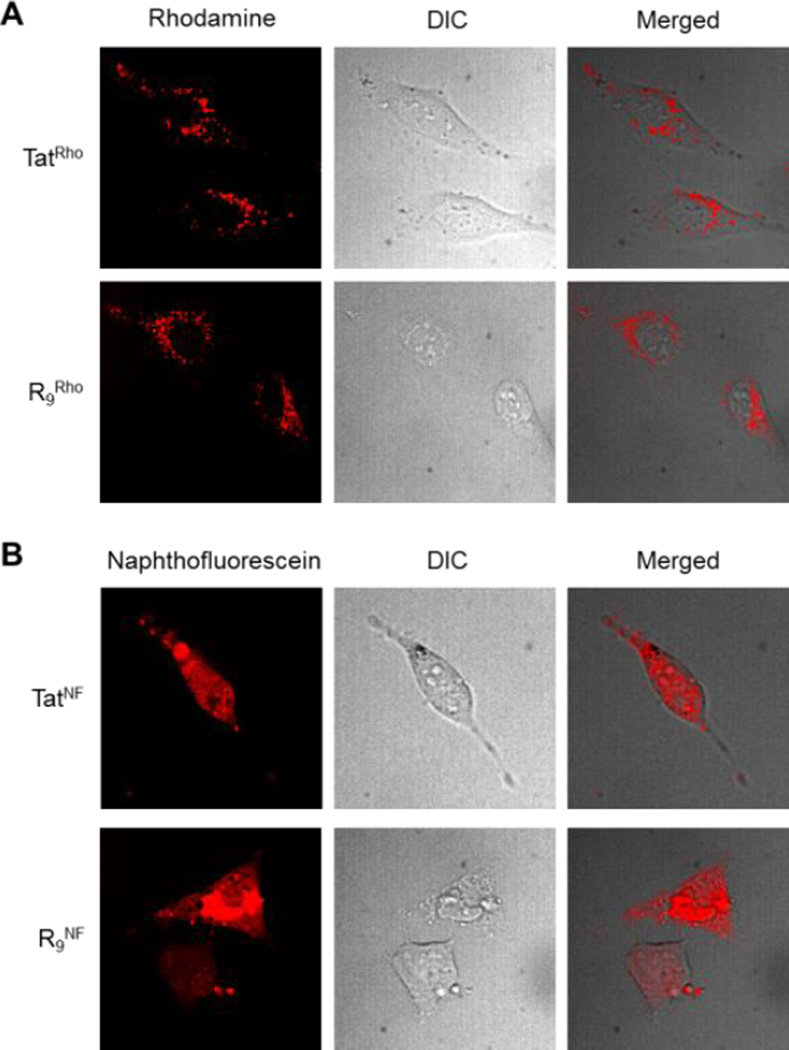

To test the suitability of NF as a specific reporter of cytosolic delivery, we labelled three CPPs of varying endosomal escape capabilities, Tat, R9, and cFΦR4, with NF or the pH-insensitive Rho. Tat and R9 have low endosomal escape efficiencies and are mostly entrapped in the endosomes.4 One study reported a cytosolic delivery efficiency of <1% for a Tat-protein conjugate.4a On the other hand, cFΦR4 has previously been shown to have 4–12-fold higher cytosolic delivery efficiency than Tat and R9, apparently due to a more efficient endosomal escape mechanism.8 Consistent with the earlier reports, HeLa cells treated with Rho-labelled Tat (TatRho) or R9 peptide (R9Rho) (5 µM for 2 h) exhibited predominantly punctate fluorescence patterns in the cytoplasmic region (Fig. 2A). In a stark contrast, cells treated with 5 µM NF-labelled Tat and R9 (TatNF and R9NF, respectively) showed diffuse fluorescence in both cytoplasmic and nuclear regions (Fig. 2B), although more sensitive imaging conditions were required to observe the diffuse NF signals. It is noteworthy that cells treated with 5 µM cFΦR4NF exhibited bright, diffuse fluorescence throughout the entire cell volume, which was readily detected under much gentler imaging conditions; under the same imaging parameters, the intracellular TatNF and R9NF signals were barely detectable (Fig. S3). The simplest explanation for the above observations is that both NF- and Rho-labelled CPPs (Tat and R9) efficiently entered cells via endocytosis, but were mostly entrapped inside the endosomes. While the entrapped TatRho and R9Rho peptides were fluorescent in the acidic endosomal environment (thus producing the punctate fluorescence patterns), the endosomally entrapped TatNF and R9NF were non-fluorescent. The diffuse NF fluorescence signals observed reflect the small (but significant) fraction of the TatNF and R9NF peptides that had successfully escaped from the endosomes into the cytosol. The brighter fluorescence of the cFΦR4NF treated cells (relative to TatNF and R9NF) was due to the fact that cFΦR4 has a much greater cytosolic delivery efficiency.8 Additionally, we treated HeLa cells with pharmacological agents that perturb different steps of the endocytic pathways or at low temperature and examined their effects on the cytosolic entry of cFΦR4NF by FACS analysis (Fig. S4). Endocytosis inhibitors wortmannin11 and bafilomycin,12 energy depletion with sodium azide/2-deoxy-D-glucose, or incubation at 4 °C reduced the intracellular NF fluorescence by up to 90%, strongly suggesting that cFΦR4NF entered cells by endocytosis and naphthofluorescein labeling did not alter the uptake mechanism.8 To ascertain that the observed diffuse fluorescence was not a result of membrane leakage of dead cells, we examined the cytotoxicity of cFΦR4NF and cFΦR4Rho on HeLa cells by the MTT assay.13 Neither peptide showed any significant toxicity up to 25 µM concentration (Fig. S5).

Fig. 2.

Live-cell confocal microscopic images of HeLa cells after 2-h treatment with 5 µM Rho- (A) or NF-labelled CPPs (B). Imaging conditions: Rho, 561-nm laser at 7% power and 100 ms exposure time; NF, 642-nm laser at 15% power and 400 ms exposure time.

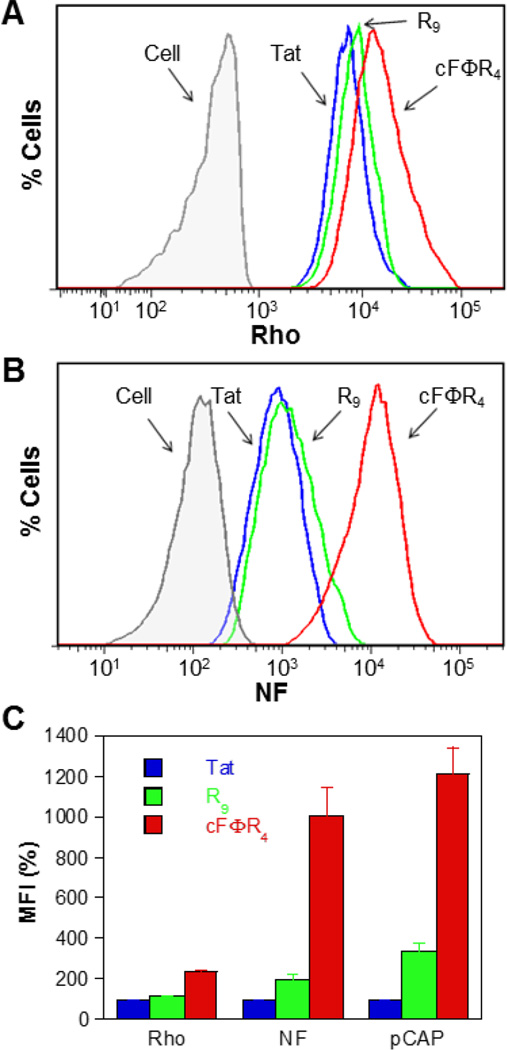

We next tested whether NF can be used to quantify the relative cytosolic delivery efficiencies of CPPs. We first treated HeLa cells with Rho-labelled peptides TatRho, R9Rho, and cFΦR4Rho (5 µM) and used FACS to assess the total cellular uptake of the CPPs. All three CPPs were efficiently internalized, with mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of 5470, 6190, and 12340 for cells treated with TatRho, R9Rho, and cFΦR4Rho, respectively (Fig. 3A). Thus, Tat and R9 were internalized by HeLa cells with similar efficiencies, whereas the uptake of cFΦR4 was 2.3-fold more efficient than Tat (Fig. 3C). Next, HeLa cells were treated with NF-labelled peptides TatNF, R9NF, or cFΦR4NF (5 µM for 2 h) and analysed by FACS (Fig. 3B). The TatNF, R9NF, and cFΦR4NF treated cells gave MFI of 1002, 1970, and 12160 AU, respectively (Fig. 3B). These data indicate that R9 has ~2-fold higher cytosolic delivery efficiency than Tat, while cFΦR4 is ~10-fold more efficient (Fig. 3C). By using the pCAP-based assay, we have previously established that R9 and cFΦR4 are 3- and 12-fold, respectively, more efficient than Tat in cytosolic delivery of cargo molecules (Fig. 3C).8 The general agreement between the data obtained by the two different assay methods thus validates NF as a simple and effective reporter to quantify the cytosolic/nuclear concentration of CPPs.

Fig. 3.

FACS analysis of the cellular uptake efficiencies of Tat, R9, and cFΦR4 peptides labeled with different fluorescent probes. (A) HeLa cells treated for 2 h with 5 µM Rho-labeled peptides (excitation at 561 nm). (B) HeLa cells treated for 2 h with 5 µM NF-labeled peptides (excitation at 633 nm). (C) Comparison of the uptake efficiencies of Tat, R9, and cFΦR4 as determined by three different methods (all values are relative to that of Tat, which is defined as 100%). The data presented have been subtracted of background fluorescence and are the mean ± SD of three independent experiments.

The availability of an effective method to determine the cytosolic concentrations of CPPs permitted us to investigate why cFΦR4 is more effective than Tat and R9 for intracellular cargo delivery. Since FACS analysis of cells treated with the Rho-labelled peptides showed that cFΦR4 was internalized 2.3-fold more efficiently than Tat, while a similar analysis of cells treated with the NF-labelled peptides revealed that the cytosolic/nuclear concentration of cFΦR4 was ~10-fold higher than that of Tat, the endosomal escape efficiency of cFΦR4 (γ, % relative to Tat) can be calculated using equation:

Thus, cyclic peptide cFΦR4 escapes from the endocytic pathway 4.3-fold more efficiently than Tat (Table 1). A similar calculation revealed that R9 is 1.7-fold more efficient than Tat in exiting the endosome. Previous studies have shown that cFΦR4 is able to escape from the early endosome, Tat exits predominantly from the late endosome/lysosome, while R9 departs from the endocytic system at a point between cFΦR4 and Tat.4e,8

Table 1.

Comparison of cellular uptake and endosomal escape efficiencies of CPPsa

| CPP | Total cellular uptake (MFIRho, %) |

Endosomal escape efficiency (γ, %) |

Cytosolic delivery (MFINF, %) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tat | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| R9 | 114 | 173 | 197 |

| cFΦR4 | 232 | 433 | 1006 |

All values are relative to Tat (100%).

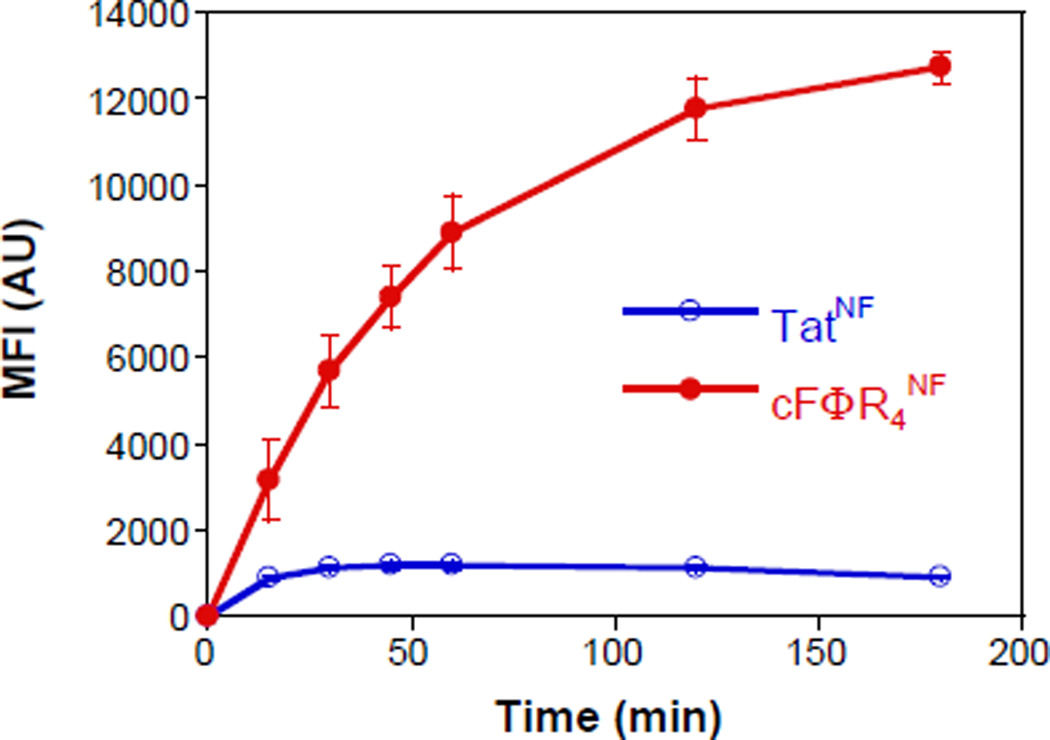

Finally, we applied the NF reporter to examine the kinetics of cytosolic entry of Tat and cFΦR4 peptides. HeLa cells were treated with TatNF or cFΦR4NF (5 µM each) and the total intracellular NF fluorescence was monitored by FACS as a function of time. The Tat peptide entered the cytosol very rapidly, reaching a maximal concentration of 1120 AU within 30 min, followed by slow decline over a 3-h period (Fig. 4). This result agrees with the previous observations by Langel and others.5,14 The cytosolic entry of cFΦR4 was even faster and continued for a much longer period of time than Tat, reaching the maximum cytosolic/nuclear concentration (~12700 AU) after 3 h.

Fig. 4.

Time dependence of the cytosolic entry by cFΦR4 and Tat. HeLa cells were treated with 5 µM TatNF or cFΦR4NF and the MFI values (after subtraction of background fluorescence and presented as the mean ± SD of three independent experiments) are plotted as a function of time.

In summary, we have shown that NF provides a simple and effective probe for quantifying the cytosolic entry of CPPs and other molecules. Amine reactive NF derivatives are commercially available and can be readily attached to any CPP. With an absorption coefficient of 4.4 × 104 M−1 cm−1 and a quantum yield of 0.14 (with excitation/emission wavelengths at 595/660 nm),9 NF is ~10-fold less sensitive than FL or Rho. However, its long absorption and emission wavelengths offer a significant advantage for in vivo studies, as it is less susceptible to interference from the background fluorescence of cellular components. While the previous methods (e.g., the disulphide-based assays5,6) may be potentially complicated by reduction of the disulphide bond by cell surface proteins15 or inside the endosome/lysosome16 or dephosphorylation of pCAP inside the endosome/lysosome, NF is not affected by any of these factors. Moreover, unlike the time-dependent enzymatic and/or chemical production of fluorescence/luminescence by the previous methods, the increase in NF fluorescence is instantaneous once an NF-labelled CPP escapes from the endosome into the cytosol, thus providing potentially better temporal resolution for visualizing certain cellular events. Like any method that requires labelling of CPPs with a hydrophobic dye, attachment of NF to a CPP may potentially alter the cellular uptake properties of the CPP. Due caution should therefore be taken when interpreting the results. Finally, our study revealed that the greater cytosolic delivery efficiency of cFΦR4 as compared to Tat and R9 is due to both enhanced cellular uptake and much improved endosomal escape capability.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Institutes of Health (Grants GM062820 and GM110208) for financial support.

Footnotes

Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) available: Experimental details and additional data.

Notes and references

- 1.(a) Copolovici DM, Langel K, Eriste E, Langel U. ACS Nano. 2014;8:1972. doi: 10.1021/nn4057269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Brock R. Bioconjugate Chem. 2014;25:863. doi: 10.1021/bc500017t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Futaki S. Adv. Drug Delivery Rev. 2005;57:547. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Goun EA, Pillow TH, Jones LR, Rothbard JB, Wender PA. ChemBioChem. 2006;7:1497. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200600171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Bechara C, Sagan S. FEBS Lett. 2013;587:1693. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.(a) Frankel AD, Pabo CO. Cell. 1988;55:1189. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90263-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Green M, Loewenstein PM. Cell. 1988;55:1179. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90262-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.(a) Richard JP, Melikov K, Vives E, Ramos C, Verbeure B, Gait MJ, Chernomordik LV, Lebleu B. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:585. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M209548200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Duchardt F, Fotin-Mleczek M, Schwarz H, Fischer R, Brock R. Traffic. 2007;8:848. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2007.00572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.(a) Kaplan IM, Wadia JS, Dowdy SF. J. Controlled Release. 2005;102:247. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2004.10.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) El-Sayed A, Futaki S, Harashima H. AAPS J. 2009;11:13. doi: 10.1208/s12248-008-9071-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Varkouhi AK, Scholte M, Storm G, Haisma HJ. J. Controlled Release. 2011;151:220. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2010.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Erazo-Oliveras A, Muthukrishnan N, Baker R, Wang TY, Pellois JP. Pharmaceuticals. 2012;5:1177. doi: 10.3390/ph5111177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Appelbaum JS, LaRochelle JR, Smith BA, Balkin DM, Holub JM, Schepartz A. Chem. Biol. 2012;19:819. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.(a) Hallbrink M, Floren A, Elmquist A, Pooga M, Bartfai T, Langel U. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2001;1515:101. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2736(01)00398-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Cheung JC, Chiaw PK, Deber CM, Bear CE. J. Controlled Release. 2009;137:2. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2009.02.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Mager I, Eiriksdottir E, Langel K, Andaloussi SE, Langel U. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2010;1798:338. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2009.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Eiriksdottir E, Mager I, Lehto T, Andaloussi SE, Langel U. Bioconjugate Chem. 2010;21:1662. doi: 10.1021/bc100174y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.(a) Jones LR, Goun EA, Shinde R, Rothbard JB, Contag CH, Wender PA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:6526. doi: 10.1021/ja0586283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Wender PA, Goun EA, Jones LR, Pillow TH, Rothbard JB, Shinde R, Contag CH. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2007;104:10340. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0703919104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.(a) Yu P, Liu B, Kodadek T. Nat. Biotechnol. 2005;23:746. doi: 10.1038/nbt1099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Holub JM, LaRochelle JR, Appelbaum JS, Schepartz A. Biochemistry. 2013;52:9036. doi: 10.1021/bi401069g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.(a) Qian Z, Liu T, Liu Y-Y, Briesewitz R, Barrios AM, Jhiang SM, Pei D. ACS Chem. Biol. 2013;8:423. doi: 10.1021/cb3005275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Qian Z, LaRochelle JR, Jiang B, Lian W, Hard RL, Selner NG, Luechapanichkul R, Barrios AM, Pei D. Biochemistry. 2014;53:4034. doi: 10.1021/bi5004102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.(a) Lee LG, Berry GM, Chen C-H. Cytometry. 1989;10:151. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990100206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Xu K, Tang B, Huang H, Yang G, Chen Z, Li P, An L. Chem. Commun. 2005:5974. doi: 10.1039/b512440a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.(a) Tycko B, Keith CH, Maxfield FR. J. Cell Biol. 1983;97:1762. doi: 10.1083/jcb.97.6.1762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Murphy RF, Powers S, Cantor CR. J. Cell Biol. 1984;98:1757. doi: 10.1083/jcb.98.5.1757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li G, D’Souza-Schorey C, Barbieri MA, Roberts RL, Klippel A, Williams LT, Stahl PD. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1995;92:10207. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.22.10207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoshimori T, Yamamoto A, Moriyama Y, Futai M, Tashiro Y. J. Biol. Chem. 1991;266:17707. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mosmann TJ. J. Immunol. Methods. 1983;65:55. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.(a) Suzuki T, Futaki S, Niwa M, Tanaka S, Ueda K, Sugiura Y. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:2437. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110017200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Jones SW, Christison R, Bundell K, Voyce CJ, Brockbank SM, Newham P, Lindsay MA. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2005;145:1093. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (c) Mager I, Langel K, Lehto T, Eiriksdottir E, Langel U. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2012;1818:502. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2011.11.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aubry S, Burlina F, Dupont E, Delaroche D, Joliot A, Lavielle S, Chassaing G, Sagan S. FASEB J. 2009;23:2956. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-127563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.(a) Collins DS, Unanue ER, Harding CV. J Immunol. 1991;147:4054. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Arunachalam B, Phan UT, Geuze HJ, Cresswell P. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2000;97:745. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.2.745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.