Abstract

Background

Although activated partial prothrombin time (aPTT) has often been used as a biomarker for evaluating the safety of dabigatran use in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF), the optimal frequency of aPTT measurements is unclear. This study aimed to identify the frequency distribution of aPTT measurements in clinical practice and its clinical significance.

Methods

This was a retrospective cooperative study conducted in 2 sites. All NVAF patients who underwent aPTT measurements before and after dabigatran treatment were included (n=380). The patients were divided into 2 groups according to the frequency of aPTT measurements during the first 3 months after drug prescription: Group A: infrequent group with only 1 measurement; and Group B: frequent group with ≥2 measurements. The clinical characteristics and outcomes were compared between the groups.

Results

The frequency of aPTT measurements in the 3 months after dabigatran initiation varied: 240 patients underwent 1 measurement (Group A), and the remaining 140 patients underwent repeated measurements (Group B). There were significant differences in age and creatinine clearance (Ccr) between the groups (Group A vs. Group B: age 64.0±11.7 vs. 67.0±11.1 years, p=0.01; Ccr 83.8±30.3 vs.76.7±31.1 mL/min, p=0.03). During the mean follow-up period of 310 days, there were no significant differences in the discontinuation rate and incidence of bleeding (17% vs. 15% and 5% vs. 3%, respectively; both not significant). In Group B, the aPTT rarely increased beyond twice the upper normal limit within the 3 months (2.1%), although the correlation between the initial and subsequent aPTT measurements was low (r=0.366).

Conclusions

In this retrospective study, the frequency of aPTT measurements after dabigatran initiation might have been dependent on patient characteristics. However, frequent aPTT measurements did not lead to a reduction in adverse clinical events.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, Dabigatran, aPTT, Bleeding

1. Introduction

Although routine laboratory monitoring is not required during dabigatran treatment, activated partial prothrombin time (aPTT) has often been used as a biomarker for evaluating the safety of dabigatran use in Japan [1,2]. Determining the anticoagulant effect of the drug and/or its concentration might help avoid adverse events, including major bleeding, because the optimum drug concentration varies depending on the patient [3]. Previous studies have shown that the aPTT varies in patients taking dabigatran [1], and in the RE-LY study, a remarkably high aPTT was related to the occurrence of major bleeding [4].

Professional organizations such as the International Society on Thrombosis and Haemostasis and the British Committee for Standards in Haematology recently recognized the need to develop guidelines detailing the appropriate time and method for evaluating patients receiving novel oral anticoagulants using coagulation tests [5]. However, the recommendations [5,6] are based on limited data obtained using different coagulation assays that focused on the relationships between drug concentration and biomarker levels.

According to these guidelines [5,6], biomarker levels may be measured just after initiation of dabigatran treatment to ascertain the safety of continuing the drug; the measurement need not be performed frequently because of its stable pharmacokinetic profile. However, in clinical situations, there is a concern that fluctuations in biomarker levels or changes in the clinical condition of patients might increase the frequency of biomarker measurements, and this may result in over monitoring. This multicenter study aimed to identify the optimum frequency of aPTT measurements for patients on therapy with dabigatran in Japan and to determine whether the frequency of the measurements resulted in different outcomes in patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF).

2. Methods

2.1. Study patients

The present study is a cooperative retrospective study performed in 2 centers: The Cardiovascular Institute and Dokkyo Medical University Hospital. The study was approved by the ethics committees of these institutions. We screened all consecutive outpatients who were newly prescribed dabigatran and underwent aPTT measurement before and just after initiation from March 2011 until November 2012. Finally, we recruited 380 patients to the present study.

2.2. Frequency of aPTT measurements and clinical outcomes

aPTT measurements were taken during the daytime in the outpatient clinic for all patients. First, we identified the frequency of aPTT measurements during the 3 months after drug initiation. The patients were divided into 2 groups according to the frequency of aPTT measurements: Group A (infrequent group) comprised patients who underwent only 1 measurement during the first 3 months, and Group B (frequent group) comprised patients who underwent ≥2 measurements. All the clinical records were reviewed from drug prescription to drug discontinuation or March 2013, whichever was earlier. Adverse events included stroke, systemic embolism, major/minor bleeding, and gastrointestinal symptoms. The rate of discontinuation for any reason was calculated.

2.3. Correlation between initial and subsequent aPTT measurements

In addition to the comparison of clinical outcomes between the groups, the correlation between the initial and subsequent aPTT values measured within 3 months was analyzed for Group B patients to determine the significance of repeated aPTT measurements.

2.4. Statistical analysis

Categorical and consecutive data are presented as number (%) and mean±standard deviation, respectively. The chi-square test and unpaired t-test were used for group comparisons. Correlation between aPTT and different sampling days was performed using Pearson׳s correlation coefficient. Statistical significance was set at a 2-sided p value <0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Patient characteristics and frequency of aPTT measurements

The frequency of aPTT measurements within 3 months after dabigatran initiation varied (Fig. 1). Most patients (n=240, 63%) underwent only 1 aPTT measurement just after drug initiation (Group A). The remaining patients (n=140, 37%) underwent repeated measurements within 3 months, with the majority having undergone 2 measurements (Group B).

Fig. 1.

Frequency distribution of the number of aPTT measurements within 3 months after dabigatran initiation.

The characteristics of the Group A and B patients are presented in Table 1. Among the clinical variables, patient age and creatinine clearance (Ccr) were significantly different between the groups: Group A patients were younger (64.0±11.7 vs. 67.0±11.1 years, p=0.01) and had higher Ccr values (83.8±30.3 vs.76.7±31.1 mL/min, p=0.03) than Group B patients. Besides these, there were no significant differences in patient background between the groups.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics.

| Group A infrequent measurement group (n=240) | Group B frequent measurement group (n=140) | pValue | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (mean±SD) years | 64.0±11.7 | 67.0±11.1 | 0.01⁎ |

| Male (%) | 73.8 | 74.3 | 1.00 |

| CHADS2score (mean) | 1.20 | 1.32 | 0.34 |

| Ccr (mean±SD) | 83.8±30.3 | 76.7±31.1 | 0.03⁎ |

| Dabigatran dosage | |||

| (150 mg b.i.d.) | 37.5 | 31.4 | 0.26 |

| Previous VKA treatment (%) | 28.3 | 20.7 | 0.11 |

| Concomitant use of APT (%) | 9.6 | 5.0 | 0.11 |

Group A – aPTT infrequent measurement group: ≤1 aPTT measurement/3 months.

Group B – aPTT frequent measurement group: ≥2 aPTT measurements/3 months.

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; Ccr, creatinine clearance rate; VKA, vitamin K antagonist; and APT, antiplatelet therapy.

Statistically significant (p<0.05).

3.2. Clinical course during the follow-up period

Neither stroke nor systemic embolism occurred during the mean follow-up period of 310.0±215.8 days. The rate of discontinuation for any reason and other clinical events in Group A and B patients are shown in Table 2. Although the rate of scheduled short-term discontinuation for cardioversion and catheter ablation was higher in Group A (58 patients, 24%) than in Group B (18 patients, 13%, p<0.01), the discontinuation rate for any other reason was not significantly different between the groups (17% vs. 15%, p=0.77). No major bleeding requiring hospitalization was observed. Minor bleeding events occurred in 11 (5%) and 4 patients (3%) in Groups A and B, respectively. There was no statistically significant difference in the rate of minor bleeding between the groups.

Table 2.

Discontinuation and clinical events.

| Discontinuation | Group A infrequent measurement (n=240) | Group B frequent measurement (n=140) | p (χ2 test) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total no. discontinued | 98 (41%) | 39 (28%) | 0.01⁎ |

| For short-term use | 58 (24%) | 18 (13%) | <0.01⁎ |

| Other reasons for discontinuation | 40 (17%) | 21 (15%) | 0.77 |

| Prolonged aPTT | 3 (1%) | 4 (3%) | 0.26 |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 10 (4%) | 3 (2%) | 0.38 |

| Minor bleeding | 2 (0.8%) | 3 (2%) | 0.36 |

| Others | 25 (10%) | 11 (8%) | 0.47 |

| Clinical events | |||

| Stroke or systemic embolism | 1 (0.4%) | 0 (0%) | 1.000 |

| Hemorrhagic events | |||

| Any bleeding | 11 (5%) | 4 (3%) | 0.58 |

| Bleeding requiring hospitalization | 0 | 0 | |

| Minor bleeding | 11 (5%) | 4 (3%) | 0.41 |

| Discontinued/continued | 2/11 | 3/4 | |

Statistically significant (p<0.05).

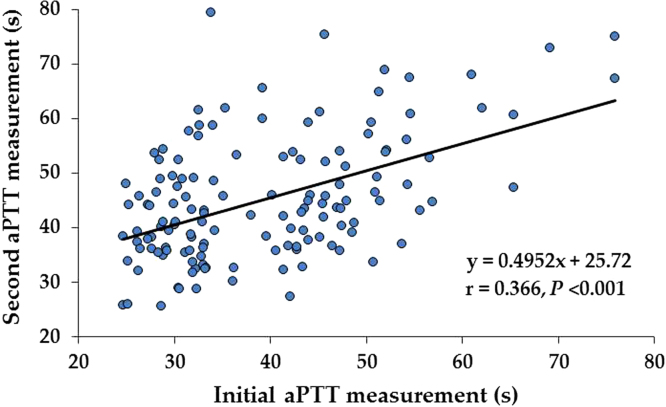

3.3. Correlation between initial and second aPTT measurements within 3 months after drug initiation

Among Group B patients with repeated aPTT measurements within 3 months, the correlation between the initial and second aPTT is shown in Fig. 2. There was a statistically significant correlation between the 2 values, but the correlation coefficient was unexpectedly low (r=0.366). However, in patients in whom the initial aPTT value was below 2 times the upper normal limit (n=138), the second aPTT value also rarely increased beyond that value (n=3, 2.1%).

Fig. 2.

Correlation between the initial and second aPTT measurements within 3 months after dabigatran initiation in Group B patients. There was a statistically significant correlation between the 2 values.

4. Discussion

The major findings of this retrospective study were as follows: (1) the frequency of aPTT measurements after dabigatran initiation was widely distributed and seemed to depend on patient characteristics including age and renal function; (2) no significant differences in the rates of discontinuation and bleeding were observed between patients with and without frequent aPTT measurements within 3 months; and (3) the repeated aPTT measurements obtained within 3 months rarely exceeded the safety margin if the initial value was acceptable.

Although routine laboratory monitoring is not needed for patients receiving therapy with dabigatran, aPTT has been frequently used as a biomarker of dabigatran usage in Japan [1,2]. Indeed, some studies reported a wide variation in aPTT values of patients under therapy with dabigatran, suggesting the utility of this biomarker in clinical practice [1,2]. Nonetheless, the correlation between the serum dabigatran concentration and aPTT is neither sensitive nor linear [7–9], and the relationship between aPTT and subsequent clinical events is unclear. Although measuring aPTT in patients under therapy with dabigatran has some limitations, this biomarker may provide some valuable information in certain situations, e.g., drug initiation in patients at high risk of bleeding, invasive procedures, and major bleedings. Even in such cases, aPTT measurement is not used for “monitoring” the way prothrombin time/international normalized ratio is used during treatment with warfarin but is used for “checking” bleeding alone.

In this retrospective study, we examined the frequency of aPTT measurements within 3 months after dabigatran initiation. In approximately two-thirds of the patients, the measurement was limited to 1 occasion. This usage is rational if aPTT measurement is not used for monitoring but for checking. However, in the remaining patients, the frequency was ≥2 within 3 months. The difference in patient characteristics may explain, at least in part, this increased frequency of measurement: Group B patients were older with a worse renal function than Group A patients. Attending physicians might attempt to repeatedly ascertain the safety of dabigatran use in these particular patients. During the study period, a blue letter (safety advisory) was issued by the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare in August 2011 that emphasized on the importance of increased frequency of measurements.

This retrospective study included various frequencies of aPTT measurements and attempted to examine whether repeated assessment of aPTT in the short term affected the subsequent clinical course of the patients. Because of the limited number of patients, we could not assess the effect of repeated assessments on the rates of stroke, systemic embolism, and major bleeding but could only determine its association with discontinuation for any reason and minor bleeding, which was not significant. The pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of dabigatran are stable and different from those of warfarin [10,11]. Therefore, if the initial aPTT value is acceptable, repeated measurements within a short period would add no valuable information. However, when a patient׳s condition changes dramatically, as in the cases of dehydration, renal failure, or congestive heart failure, our finding would not hold true with respect to not performing frequent aPTT measurements after drug initiation.

In Group B, we examined the correlation between the initial and second aPTT measurements after dabigatran initiation. The correlation was statistically significant but the coefficient was lower than expected. The low correlation could be attributed to many reasons including time of drawing blood relative to that of drug intake, day-to-day variation in drug absorption, or renal excretion. Fluctuating biomarker levels are not significant in some instances and meaningful in others. The aPTT measurement during dabigatran treatment helps assess overuse of dabigatran, and only a high aPTT would have clinical significance. Therefore, fluctuations below twice the upper normal limit within 3 months, as observed in the present study, should be considered physiological fluctuations. This should be considered when using the value repeatedly.

There are several limitations to the present study. The number of patients was small and the follow-up period was too short to analyze the incidence of stroke and major bleeding. The analysis was retrospective, and therefore, could not be free from bias. Group B patients were older and had worse renal function than Group A patients, probably leading to bias with respect to the attending physician. Nevertheless, to the best of our knowledge, the present study is the first to determine the correlation between the frequency of aPTT measurement and subsequent short-term clinical course after dabigatran initiation. The present study did not demonstrate any benefit of frequent aPTT measurement. Nonetheless, prospective randomized studies would be required to determine the optimal number of aPTT measurements during dabigatran treatment.

Conflict of interest

Dr. Yamashita received research funding from Boehringer Ingelheim and Daiichi-Sankyo and remuneration from Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi-Sankyo, Bayer Healthcare, Pfizer, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Eisai, and Ono Pharmaceutical Co.

References

- 1.Suzuki S., Otsuka T., Sagara K. Dabigatran in clinical practice for atrial fibrillation with special reference to activated partial thromboplastin time. Circ J. 2012;76:755–757. doi: 10.1253/circj.cj-11-1335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kawabata M., Yokoyama Y., Sasano T. Bleeding events and activated partial thromboplastin time with dabigatran in clinical practice. J Cardiol. 2013;62:121–126. doi: 10.1016/j.jjcc.2013.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Douxfils J., Mullier F., Robert S. Impact of dabigatran on a large panel of routine or specific coagulation assays. Laboratory recommendations for monitoring of dabigatran etexilate. Thromb Haemost. 2012;107:985–997. doi: 10.1160/TH11-11-0804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Connolly S.J., Ezekowitz M.D., Yusuf S. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1139–1151. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baglin T., Keeling D., Kitchen S. Effects on routine coagulation screens and assessment of anticoagulant intensity in patients taking oral dabigatran or rivaroxaban: guidance from the British Committee for Standards in Haematology. Br J Haematol. 2012;159:427–429. doi: 10.1111/bjh.12052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tripodi A., Di Iorio G., Lippi G. Position paper on laboratory testing for patients taking new oral anticoagulants. Consensus document of FCSA, SIMeL, SIBioC and CISMEL1. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2012;50:2137–2140. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2012-0327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hapgood G., Butler J., Malan E. The effect of dabigatran on the activated partial thromboplastin time and thrombin time as determined by the Hemoclot thrombin inhibitor assay in patient plasma samples. Thromb Haemost. 2013;110:308–315. doi: 10.1160/TH13-04-0301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hawes E.M., Deal A.M., Funk-Adcock D. Performance of coagulation tests in patients on therapeutic doses of dabigatran: a cross-sectional pharmacodynamic study based on peak and trough plasma levels. J Thromb Haemost. 2013;11:1493–1502. doi: 10.1111/jth.12308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dager W.E., Gosselin R.C., Kitchen S. Dabigatran effects on the international normalized ratio, activated partial thromboplastin time, thrombin time, and fibrinogen: a multicenter, in vitro study. Ann Pharmacother. 2012;46:1627–1636. doi: 10.1345/aph.1R179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stangier J., Rathgen K., Stähle H. The pharmacokinetics, pharmacodynamics and tolerability of dabigatran etexilate, a new oral direct thrombin inhibitor, in healthy male subjects. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;64:292–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2007.02899.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stangier J., Stähle H., Rathgen K. Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of the direct oral thrombin inhibitor dabigatran in healthy elderly subjects. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2008;47:47–59. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200847010-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]