New treatments, rapid and inexpensive identification methods, and measures to contain nosocomial transmission and outbreaks are urgently needed.

Keywords: Mycobacterium abscessus complex, Mycobacterium abscessus, Mycobacterium massiliense, Mycobacterium bolletii, multidrug resistant, nontuberculous, mycobacteria, outbreaks, cosmetic procedures, nosocomial, transmission, taxonomy, nomenclature, clinical disease, bacteria, identification methods

Abstract

Mycobacterium abscessus complex comprises a group of rapidly growing, multidrug-resistant, nontuberculous mycobacteria that are responsible for a wide spectrum of skin and soft tissue diseases, central nervous system infections, bacteremia, and ocular and other infections. M. abscessus complex is differentiated into 3 subspecies: M. abscessus subsp. abscessus, M. abscessus subsp. massiliense, and M. abscessus subsp. bolletii. The 2 major subspecies, M. abscessus subsp. abscessus and M. abscessus subsp. massiliense, have different erm(41) gene patterns. This gene provides intrinsic resistance to macrolides, so the different patterns lead to different treatment outcomes. M. abscessus complex outbreaks associated with cosmetic procedures and nosocomial transmissions are not uncommon. Clarithromycin, amikacin, and cefoxitin are the current antimicrobial drugs of choice for treatment. However, new treatment regimens are urgently needed, as are rapid and inexpensive identification methods and measures to contain nosocomial transmission and outbreaks.

Mycobacteria are divided into 2 major groups for the purpose of diagnosis and treatment: Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex, which comprises M. tuberculosis, and nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM), which comprise all of the other mycobacteria species that do not cause tuberculosis. NTM can cause pulmonary disease resembling tuberculosis, skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs), central nervous system infections, bacteremia, and ocular and other infections (1,2). Over the past decade, the number of NTM disease cases worldwide has markedly increased (3,4), and the upsurge cannot be explained solely by increased awareness among physicians and advances in laboratory methods (3).

M. abscessus complex is a group of rapidly growing, multidrug-resistant NTM species that are ubiquitous in soil and water (1). Species comprising M. avium complex (MAC) are the most common NTM species responsible for disease; however, infections caused by M. abscessus complex are more difficult to treat because of antimicrobial drug resistance (5). M. abscessus complex is also resistant to disinfectants and, therefore, can cause postsurgical and postprocedural infections (2,5). Although M. abscessus complex most commonly causes SSTIs and pulmonary infections, the complex can also cause disease in almost all human organs (2,5). To improve our understanding of M. abscessus complex infections, we reviewed the epidemiology and clinical features of and treatment and prevention measure for diseases caused by the organisms as well as the taxonomy and antimicrobial susceptibilities of these organisms.

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

We performed a PubMed search for M. abscessus complex articles published during January 1990–December 2014, using the following search terms: M. abscessus, M. abscessus subsp. abscessus, M. abscessus subsp. bolletii, M. abscessus subsp. massiliense, M. massiliense, M. bolletii, and nontuberculous mycobacteria. Only articles published with abstracts in English were selected.

Taxonomy and Epidemiology

Bacterial Classification

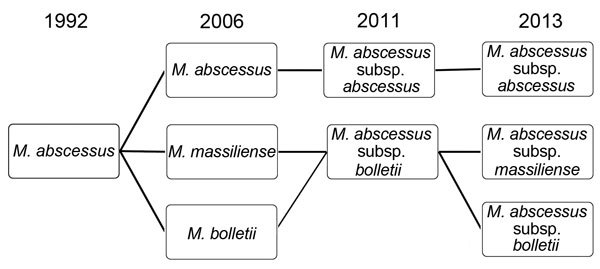

M. abscessus was first isolated from a knee abscess in 1952 (1). M. abscessus and M. chelonae were originally considered to belong to the same species (“M. chelonei” or “M. chelonae”), but in 1992, M. abscessus was reclassified as an individual species (1). After M. abscessus was recognized as an independent species, new subspecies, including M. massiliense and M. bolletii, were discovered. Debate has ensued over whether M. massiliense and M. bolletii should be reunited to form one subspecies, M. abscessus subsp. bolletii (6). It is hoped that the debate will be settled as a result of findings from several recent studies that clearly demonstrated, by genome comparison, that M. abscessus complex comprises 3 entities: M. abscessus subsp. abscessus, M. abscessus subsp. massiliense, and M. abscessus subsp. bolletii (7–11). Serial changes in the taxonomic classification and nomenclature of M. abscessus complex, from 1992 to 2013, are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Serial changes in the nomenclature and taxonomic classification of Mycobacterium abscessus complex, 1992–2013.

M. abscessus subsp. bolletii is recognized as a rare pathogen with a functional inducible erythromycin ribosome methyltransferase (erm) (41) gene. In most M. abscessus subsp. abscessus mycobacterium, this gene leads to macrolide resistance. M. abscessus subsp. massiliense has been proposed to have a nonfunctional erm(41) gene, leading to macrolide susceptibility and a favorable treatment outcome for infections (7–11).

Laboratory Identification

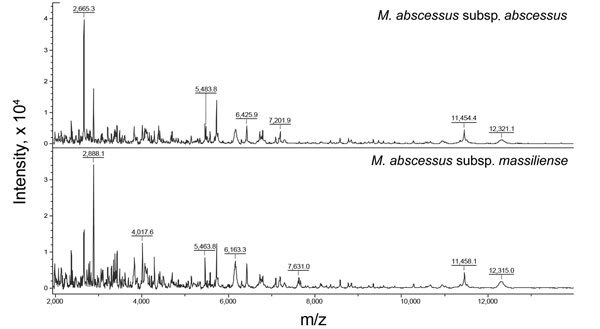

Definitive diagnosis of M. abscessus complex infection in humans is invariably determined by the isolation of M. abscessus complex from clinical specimens. The correct subspecies identification of M. abscessus complex has traditionally relied on phenotypic methods (e.g., biochemical testing for the utilization of citrate) to distinguish them from closely related species like M. chelonae (1). However, this method is not accurate enough to differentiate between the 2 main subspecies of the complex. Instead, rpoB gene–based sequencing is a more reliable method for correctly identifying M. abscessus complex to the subspecies level (10). However, because of the limited differences between the subspecies of M. abscessus complex, some researchers have questioned the accuracy of identification results from the sequencing of a single gene, especially the rpoB gene (10). Many schemes have been used in an attempt to accurately differentiate between subspecies, such as multilocus gene sequence typing, sequencing of the erm gene, and matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (Figure 2) (10,12). Nonetheless, because the taxonomic classification is still changing, the debate over the optimal identification method will probably also continue.

Figure 2.

Spectrum of Mycobacterium abscessus subsp. abscessus and M. abscessus subsp. massiliense created by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry Biotyper system (Microflex LT; Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Bremen, Germany). The absolute intensities of the ions are shown on the y-axis, and the masses (m/z) of the ions are shown on the x-axis. The m/z values represent the mass-to-charge ratio.

Disease Burden

The global isolation and epidemiology of M. abscessus complex are diverse. Furthermore, due to limitations in correct and detailed species identification, previous epidemiologic studies often referred to M. abscessus complex as M. chelonae/abscessus group or rapidly growing mycobacteria (13). In the United States, M. abscessus/chelonae complex infections are secondary only to MAC infections, compromising 2.6%–13.0% of all mycobacterial pulmonary infections across various study sites. This percentage correlates to an annual prevalence of <1 M. abscessus/chelonae pulmonary infections per 100,000 population, but the prevalence is increasing (13). M. abscessus complex is especially prevalent in East Asia. For example, in Taiwan, M. abscessus complex comprises 17.2% of all clinical NTM isolates, which correlates to 1.7 cases/100,000 population (4). According to current studies, the proportion of M. abscessus subsp. massiliense and M. abscessus subsp. abscessus is about the same among all clinical isolates (12). M. abscessus subsp. bolletii is rarely isolated (7).

Clinical Diseases

Respiratory Tract Infections

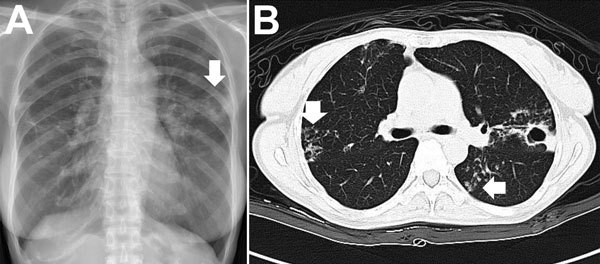

M. abscessus complex can cause pulmonary disease, especially in vulnerable hosts with underlying structural lung disease, such as cystic fibrosis, bronchiectasis, and prior tuberculosis (2). M. abscessus complex pulmonary disease usually follows an indolent, but progressive, course, causing persistent symptoms, decline of pulmonary function, and impaired quality of life; however, the disease can also follow a fulminant course with acute respiratory failure (2,14). Establishing a diagnosis of pulmonary disease due to M. abscessus complex is not straightforward because isolation of M. abscessus complex from respiratory samples is not, in and of itself, diagnostic of pulmonary disease (2). According to guidelines published by the American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America in 2007, the diagnosis of M. abscessus complex pulmonary disease requires the fulfillment of clinical and microbiological criteria, such as the presence of clinical symptoms; radiographic evidence of lesions compatible with NTM pulmonary disease; appropriate exclusion of other diseases; and, in most circumstances, positive culture results from at least 2 separate expectorated sputum samples (2). Common radiographic findings of M. abscessus complex pulmonary infection (i.e., bronchiolitis; bronchiectasis; nodules; consolidation; and, less frequently, cavities) are shown in Figure 3 (2).

Figure 3.

Chest radiograph (A) and computed tomography scan (B) images for a patient with pulmonary disease due to Mycobacterium abscessus subsp. abscessus. A) The arrow indicates a cavity with surrounding consolidation over the left upper lung. B) Vertical arrow indicates bronchiectasis; horizontal arrow indicates nodules.

M. abscessus complex is especially prevalent in respiratory specimens from patients with cystic fibrosis (7,15). Recent studies have shown that M. abscessus complex infection is no longer a contraindication for lung transplantation, although postoperative complications and a prolonged treatment course can be expected (7).

Pulmonary disease caused by M. abscessus complex is notoriously difficult to treat. Although there is no standard treatment, current guidelines suggest the administration of macrolide-based therapy in combination with intravenously administered antimicrobial agents; however, this regimen has been shown to have a substantial cytotoxic effect (2). Of 65 patients with pulmonary disease due to M. abscessus complex who received an initial 4-week course of intravenous antimicrobial agents followed by macrolide-based combination therapy, 38 (58%) had M. abscessus–negative sputum samples >12 months after treatment (16). Surgical resection of localized disease in addition to antimicrobial therapy has been shown to elicit a longer microbiologic response than antimicrobial agents alone: sputum samples were M. abscessus complex–negative for at least 1 year in 57% versus 28% of these treatment groups, respectively (17). According to the 2007 American Thoracic Society/Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines, the treatment options remain limited with current antimicrobial agents, and M. abscessus complex pulmonary disease is still considered a chronic incurable disease (2).

The advancement of subspecies differentiation has allowed for more effective management of pulmonary disease caused by M. abscessus complex. For example, unlike M. abscessus subsp. abscessus, M. abscessus subsp. massiliense does not have inducible resistance to clarithromycin (7). Therefore, knowing that a patient’s infection is due to M. abscessus subsp. massiliense rather than 1 of the other 2 subspecies enables the physician to confidently administer clarithromycin (7,18). In a large study on treatment outcome in patients with pulmonary disease caused by M. Abscessus subsp. massiliense or M. abscessus subsp. abscessus, all patients had similar clinical signs, radiographic findings, and treatment regimens (18). However, after treatment, the percentage of patients who had negative sputum culture results was much higher in the M. abscessus subsp. massiliense–infected group (88%) than in the M. abscessus subsp. abscessus–infected group (25%) (18). The lack of efficacy of clarithromycin-containing antimicrobial therapy against M. abscessus subsp. abscessus isolates in the study could be explained by the subspecies’ inducible resistance to clarithromycin. The study clearly demonstrated how M. abscessus subsp. massiliense and M. abscessus subsp. abscessus have different susceptibility profiles to combination therapy containing clarithromycin and different outcomes from such treatment (18).

SSTIs

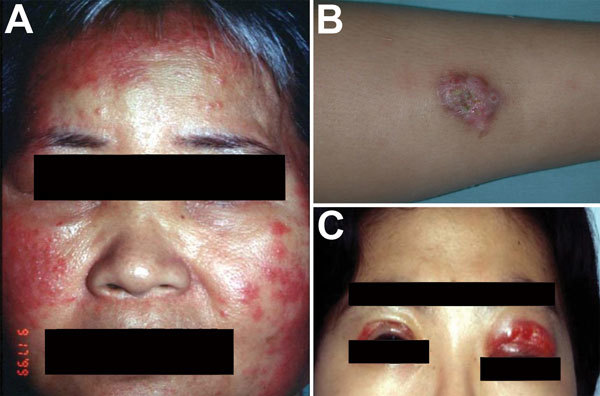

SSTIs are also commonly caused by M. abscessus complex; infections range from deep tissue infections to localized skin infections. The 2 major mechanisms for acquiring an M. abscessus complex–associated SSTI are by 1) direct contact with contaminated material or water through traumatic injury, surgical wound, or environmental exposure and 2) secondary involvement of skin and soft tissue during disseminated disease (19). SSTIs caused by M. abscessus complex have been reported in patients who recently underwent cosmetic procedures (e.g., mesotherapy), tattooing, and acupuncture (19). M. abscessus complex SSTIs can also develop after exposure to environmental sources, such as spas and hot springs (19,20). More often, however, these SSTIs develop among hospitalized postsurgical patients, in whom surgical wound infections are most commonly due to M. abscessus subsp. massiliense (21,22). Disseminated M. abscessus complex infections with skin and soft tissue involvement also commonly occur (23). Of note, however, the presence of M. abscessus complex SSTIs can result in or from disseminated M. abscessus complex infections (23). M. abscessus complex skin infection have diverse presentations, including cutaneous nodules (usually tender), erythematous papules/pustules, and papular eruptions or abscesses (Figure 4) (19).

Figure 4.

Skin lesions caused by Mycobacterium abscessus subsp. abscessus. A) Diffuse erythematous papular eruptions on the face and bilateral cervical lymphadenitis in a middle-aged man. B) A circumscribed subcutaneous nodule with pus discharge on the right arm of a 12-year-old boy. C) Wound infection over both upper eyelids of a 36-year-old woman; the infection developed 1 week after cosmetic surgery.

Central Nervous System Infections

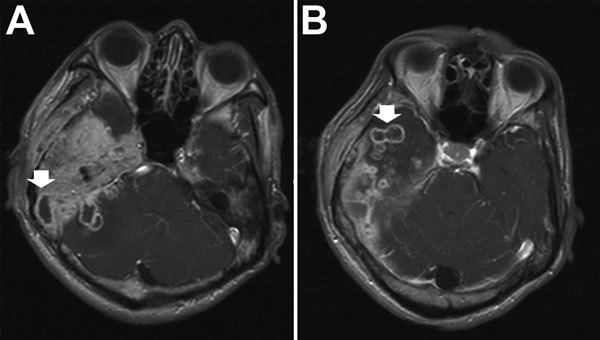

Central nervous system (CNS) infections caused by M. abscessus complex are rare, but when they do occur, meningitis and cerebral abscesses are the most common manifestations (Figure 5). Although MAC is responsible for most NTM CNS infections, especially in HIV-infected hosts, M. abscessus complex has increasingly been reported to cause CNS infections in HIV-negative patients (21). In one study, M. abscessus was responsible for most NTM CNS infections in HIV-seronegative patients (8/11 patients), especially in patients who had undergone neurosurgical procedures, patients who had intracranial catheters, and patients with otologic diseases. Treatment outcome depended on the patient’s underlying disease and health status. Clarithromycin-based combination therapy for at least 1 year plus surgical intervention, if needed, offered the best chance for cure (21).

Figure 5.

Brain computed tomography scan images for a patient with central nervous system infection caused by Mycobacterium abscessus subsp. bolletii. Arrows indicate abnormal nodular pachymeningeal thickening and leptomeningeal and intraparenchymal extension with multiple rim-enhancing lesions in the right cerebellum (A) and right temporal lobe (B), indicating cerebral abscesses.

Disseminated Diseases and Bacteremia

Disseminated M. abscessus complex infections, such as lymphadenopathy, SSTIs, pulmonary infections, and bacteremia, are on the rise (23), and bacteremia caused by M. abscessus complex is most often associated with catheter use (24,25). A recent study showed that surgical wound infection may be the portal of entry, especially for M. abscessus subsp. massiliense (26). Optimal treatment modalities include removal of intravascular catheters, surgical debridement, and administration of intravenous antimicrobial agents chosen on the basis of drug susceptibility test results.

Disseminated M. abscessus complex infections tend to occur in immunocompromised hosts, including persons with HIV. However, these infections can also occur in HIV-negative patients. Browne et al. (23) recently showed that neutralizing anti–interferon-γ autoantibodies were present in 81% of HIV-negative patients with disseminated NTM-associated infections, and in adults, these antibodies were associated with adult-onset immunodeficiency similar to that seen in advanced HIV infection. This adult-onset immunodeficiency status can lead to disseminated NTM disease that mimics advanced HIV infection (23).

Ocular Infections

The incidence of NTM ocular infections (keratitis, endophthalmitis, scleritis, and other tissues of the ocular area) has increased over the past decade, and the increase has been attributed to the M. chelonae/abscessus group (27). Interpreting the real trend in ocular infections caused by M. abscessus complex is difficult because most studies have not used reliable tests to differentiate between M. abscessus complex and M. chelonae (27).

Initial treatment of M. abscessus complex ocular infections involves the discontinuation of topical corticosteroids, if used. The optimal treatment strategy (topical therapy, systemic antimicrobial agents, and surgical intervention) depends on the site of the ocular infection (28). Topical therapy, particularly topical amikacin and clarithromycin, can be used to treat some M. abscessus complex ocular infections (e.g., conjunctivitis, scleritis, keratitis, endophthalmitis) (28), and systemic antimicrobial agents can be used for all ocular infections (28). Surgical debridement, including removal of infected tissue, should be considered and is necessary for treatment of infections in some patients (28). Treatment outcome varies according to the site of infection, and early recognition of the infection is crucial.

Nosocomial Outbreaks and Transmission

Outbreaks of M. abscessus complex infections in hospital and clinic settings have been reported worldwide (19). Many of the outbreak events occur in clinics conducting cosmetic surgery, liposuction, mesotherapy, or intravenous infusion of cell therapy (29). Proposed sources of transmission include contaminated disinfectants, saline, and surgical instruments as well as contact transmission between patients (19,30,31).

M. abscessus complex transmission involves vulnerable hosts and causes substantial illness and death; thus, concern is also rising regarding outbreaks in centers specializing in lung transplantation and treatment of cystic fibrosis (30). Whole-genome sequencing of outbreak isolates has provided evidence of patient-to-patient transmission of M. abscessus complex; this transmission is most likely indirect rather than direct (30).

Antimycobacterial Susceptibilities

M. abscessus complex is notoriously resistant to standard antituberculous agents and most antimicrobial agents (5). The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute recommends testing rapidly growing mycobacteria for susceptibility to macrolides (clarithromycin and amikacin), aminoglycosides, fluoroquinolones, imipenem, doxycycline, tigecycline, cefoxitin, cotrimoxazole, and linezolid (32). The recommended drug susceptibility testing method is broth microdilution in cation-adjusted Mueller-Hinton broth supplemented with oleic albumin dextrose catalase (32). Among the agents suggested for M. abscessus complex susceptibility testing, clarithromycin, amikacin, and cefoxitin have the best in vitro antimycobacterial activity (7,32,33).

Recent major studies presenting susceptibility and resistance rates for M. abscessus subsp. massiliense, M. abscessus subsp. abscessus, and M. abscessus complex against 7 antimicrobial agents are summarized in Table 1. Most of the studies are from Asia, and the resistance rate for clarithromycin ranges from 0 to 38%. The resistance rates for cefoxitin (overall 15.1%) and amikacin (overall 7.7%) are also low. Doxycycline, quinolones (including moxifloxacin and ciprofloxacin), and imipenem had high resistance rates. Therefore, local susceptibility data are needed to guide treatment.

Table 1. Summary of recent data on the resistance of Mycobacterium abscessus complex bacteria to different antimicrobial agents*.

| Study authors (reference), species | No. isolates | Antimicrobial drug, no. resistant isolates/no. tested (%) |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CLR | DOX | CIP | MXF | FOX | AMK | IPM | ||

| Lee et al. (34) | ||||||||

| M. abscessus subsp. abscessus | 202 | 48/202 (24) | NA | 184/202 (91) | 167/202 (83) | NA | 25/202 (12) | NA |

|

M. abscessus subsp. massiliense |

199 |

15/199 (8) |

NA |

174/199 (87) |

149/199 (75) |

NA |

12/199 (6) |

NA |

| Koh et al. (18) | ||||||||

| M. abscessus subsp. abscessus | 64 | 3/64 (5) | 53/64 (83) | 37/64 (58) | 30/64 (47) | 0/64 | 3/64 (5) | 27/62 (44) |

|

M. abscessus subsp. massiliense |

79 |

3/79 (4) |

58/79 (73) |

48/79 (61) |

42/79 (53) |

1/79 (1) |

6/79 (8) |

50/75 (67) |

| Huang et al. (35) | ||||||||

|

M. abscessus complex |

40 |

3/40 (8) |

37/40 (93) |

36/40 (90) |

31/40 (78) |

27/40 (68) |

2/40 (5) |

35/40 (88) |

| Brown-Elliott et al. (36) | ||||||||

|

M. abscessus complex |

37 |

0% (0/37) |

NA |

29/37 (78) |

29/37 (78) |

NA |

0/37 |

7/37 (19) |

| Broda et al. (37) | ||||||||

|

M. abscessus complex |

58 |

22/58 (38) |

57/58 (98) |

55/58 (95) |

55/58 (95) |

16/58 (28) |

10/58 (17) |

56/58 (97) |

| Zhuo et al. (38) | ||||||||

|

M. abscessus complex |

70 |

10/70 (14) |

NA |

56/70 (80) |

NA |

3/70 (4) |

0/70 |

15/70 (21) |

| Overall | ||||||||

| M. abscessus complex | 749 | 104/749 (13.9) | 205/241 (85.1) | 619/749 (82.6) | 503/679 (74.1) | 47/311 (15.1) | 58/749 (7.7) | 190/342 (55.6) |

| M. abscessus subsp. abscessus | 266 | 51/266 (19.4) | 53/64 (83.0) | 221/266 (83.1) | 197/266 (74.1) | 0/64 | 28/266 (10.5) | 27/62 (44.0) |

| M. abscessus subsp. massiliense | 278 | 18/278 (6.5) | 58/79 (73.4) | 222/278 (79.8) | 191/278 (68.7) | 1/79 (1.0) | 18/278 (6.5) | 50/75 (66.7) |

*AMK, amikacin; CIP, ciprofloxacin; CLR, clarithromycin; DOX, doxycycline; FOX, cefoxitin; IPM, imipenem; MXF, moxifloxacin; NA, not available.

Because of its rarity, M. abscessus subsp. bolletii is discussed separately here. These mycobacteria are uniformly resistant to drugs recommended for use against M. abscessus complex. In one study, high MICs of tested antimycobacterial agents were observed, and amikacin probably had the highest activity (i.e., the lowest MIC) (33).

Recent studies have reported on the importance of the erm(41) gene in M. abscessus complex; this gene confers macrolide resistance through methylation of 23S ribosomal RNA (39). The erm(41) gene is present in the M. abscessus complex group but absent in M. chelonae (39). Many strains of M. abscessus subsp. massiliense have a nonfunctional erm(41) gene, and because of this, the rate of clarithromycin susceptibility is higher in M. abscessus subsp. massiliense than in M. abscessus subsp. abscessus (18). The Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute recommends testing for inducible macrolide resistance because subspecies of M. abscessus complex demonstrate susceptibility to clarithromycin during the first 3–5 days of incubation but demonstrate resistance after an extended duration of incubation (preferably 14 days, according to many experts) (39).

Another area of strenuous clinical research involves identifying and developing novel anti–M. abscessus complex agents. One such agent, the glycylcycline tigecycline, has been shown to exhibit good in vitro activity against rapidly growing mycobacteria, especially M. abscessus complex (12,21). However, no prospective trial has been conducted to evaluate the efficacy of tigecycline, and a breakpoint for interpreting tigecycline susceptibility has not been established (32).

Treatment

Several problems regarding treatment of M. abscessus complex infections in different organs are unsolved. For example, there is a lack of consensus on the optimal antimicrobial agents and combination therapy, optimal treatment duration, and the introduction of novel antimicrobial agents (e.g., tigecycline). Reports describing cases of M. abscessus complex infection are limited, except for those describing pulmonary disease and SSTIs. Thus, treatment recommendations must rely on retrospective case series. A summary of treatment recommendations from previous studies is shown in Table 2. The treatment of serious M. abscessus complex disease usually involves initial combination antimicrobial therapy with a macrolide (clarithromycin 1,000 mg daily or 500 mg twice daily, or azithromycin 250 mg–500 mg daily) plus intravenous agents for at least 2 weeks to several months followed by oral macrolide–based therapy (2). The drugs of choice for initial intravenous administration are amikacin (25 mg/kg 3×/wk) plus cefoxitin (up to 12 g/d given in divided doses) or amikacin (25 mg/kg 3×/wk) plus imipenem (500 mg 2–4×/wk) (2). As previously mentioned, the in vitro MICs of tigecycline are low, and the drug should be considered in treatment regimens.

Table 2. Summary of recommendations from previous studies for the treatment of Mycobacterium abscessus complex infections in humans.

| Type of disease (reference) | Recommended initial regimen | Recommended treatment duration |

|---|---|---|

| Pulmonary disease (2) | Macrolide-based therapy in combination with intravenous antimicrobial therapy (preferably cefoxitin and amikacin) | Continue until sputum samples are negative for M. abscessus complex for 12 mo |

| Skin and soft-tissue infection (2) | Macrolide in combination with amikacin plus cefoxitin/imipenem plus surgical debridement | Minimum of 4 mo, including a minimum of 2 wk combined with intravenous agents |

| Central nervous system infection (21) | Clarithromycin-based combination therapy (preferably including at least amikacin in the first weeks) | 12 mo |

| Bacteremia (24,25) | At least 2 active antimicrobial agents (preferably including amikacin) plus removal of catheter and/or surgical debridement of infection foci | 4 wk after last positive blood culture result |

| Ocular infection (28) | Topical agents (amikacin, clarithromycin) and/or systemic antimicrobial drugs (oral clarithromycin, intravenous amikacin or cefoxitin) and/or surgical debridement* | 6 wk to 6 mo |

*The treatment of ocular infections was highly dependent on the infection site. In some sites, >1 treatment strategies (i.e., topical or systemic antimicrobial drug treatment or surgery) should be considered.

Prevention

M. abscessus complex infection can be acquired in the community or in the hospital setting. In the community setting, water supply systems have been postulated to be the source of human infections (7,40). Membrane filtration, hyperchlorination, maintenance of constant pressure gradients, and the utilization of particular pipe materials have been suggested as methods for reducing the presence of NTM in water supply systems (7,40). In the hospital setting, disinfectant failure, contamination of medical devices and water, and indirect transmission between patients are considered to be the source of infections (19,30). In addition, clinics for cosmetic procedures have become sites of frequent outbreaks of M. abscessus complex infections (19,29). It is unclear whether patients with M. abscessus complex disease should be isolated from vulnerable hosts, such as patients with cystic fibrosis.

Conclusions

M. abscessus complex comprises a group of rapidly growing, multidrug-resistant, nontuberculous mycobacteria that are responsible for a wide spectrum of SSTIs and other infections. The complex is differentiated into 3 subspecies: M. abscessus subsp. abscessus, M. abscessus subsp. massiliense, and M. abscessus subsp. bolletii, which is rarely isolated. The major difference between M. abscessus subsp. massiliense and M. abscessus subsp. abscessus is that the former does not have an intact erm(41) gene and thus does not have inducible macrolide resistance; treatment response may thus be better among patients with infections caused by M. abscessus subsp. massiliense. M. abscessus complex can cause infections involving almost all organs, but the infections generally involve the lungs, skin, and soft tissue. Drugs with the best in vitro activity include clarithromycin, amikacin, cefoxitin, and possibly tigecycline. Treatment regimens vary according to the infection site and usually include macrolide-based combination therapy, including parenteral amikacin plus another parenteral agent (cefoxitin, tigecycline, imipenem, or linezolid), for weeks to months, followed by oral antimicrobial therapy. Evidence of nosocomial transmission and outbreaks of M. abscessus complex is increasing; therefore, strenuous infection control measures should be taken to reduce the possibility of hospital-acquired M. abscessus complex infections.

Because of the complexity of the molecular techniques needed to differentiate between M. abscessus subsp. abscessus and M. abscessus subsp. massiliense, it is difficult for most laboratories to identify the different subspecies. A more rapid and less expensive method for subspecies identification is thus needed for epidemiologic and clinical purposes. In addition, prospective trials comparing different regimens of antimicrobial agents are needed to determine the best treatment options; these studies should include novel agents, such as tigecycline. The effect of implementing isolation protocols for patients with infections due to M. abscessus complex (particularly pulmonary disease) should also be evaluated in future studies.

Biography

Dr. Lee is attending physician at the Department of Internal Medicine, National Taiwan University Hospital Hsin-Chu Branch, Hsin-Chu, Taiwan, and Department of Internal Medicine, National Taiwan University Hospital, Taipei, Taiwan. His primary research interests include emerging infections and epidemiologic and clinical research on diseases caused by nontuberculous mycobacteria.

Footnotes

Suggested citation for this article: Lee MR, Sheng WH, Hung CC, Yu CJ, Lee LN, Hsueh PR. Mycobacterium abscessus complex infections in humans. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015 Sep [date cited]. http://dx.doi.org/10.3201/eid2109.141634

References

- 1.Brown-Elliott BA, Wallace RJ Jr. Clinical and taxonomic status of pathogenic nonpigmented or late-pigmenting rapidly growing mycobacteria. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2002;15:716–46. 10.1128/CMR.15.4.716-746.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Griffith DE, Aksamit T, Brown-Elliott BA, Catanzaro A, Daley C, Gordin F, et al. An official ATS/IDSA statement: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of nontuberculous mycobacterial diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:367–416. 10.1164/rccm.200604-571ST [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marras TK, Mendelson D, Marchand-Austin A, May K, Jamieson FB. Pulmonary nontuberculous mycobacterial disease, Ontario, Canada, 1998–2010. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:1889–91. 10.3201/eid1911.130737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lai CC, Tan CK, Chou CH, Hsu HL, Liao CH, Huang YT, et al. Increasing incidence of nontuberculous mycobacteria, Taiwan, 2000–2008. Emerg Infect Dis. 2010;16:294–6. 10.3201/eid1602.090675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nessar R, Cambau E, Reyrat JM, Murray A, Gicquel B. Mycobacterium abscessus: a new antibiotic nightmare. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:810–8. 10.1093/jac/dkr578 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Leao SC, Tortoli E, Euzeby JP, Garcia MJ. Proposal that Mycobacterium massiliense and Mycobacterium bolletii be united and reclassified as Mycobacterium abscessus subsp. bolletii comb. nov., designation of Mycobacterium abscessus subsp. abscessus subsp. nov. and emended description of Mycobacterium abscessus. Int J Syst Evol Microbiol. 2011;61:2311–3. 10.1099/ijs.0.023770-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benwill JL, Wallace RJ Jr. Mycobacterium abscessus: challenges in diagnosis and treatment. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2014;27:506–10. 10.1097/QCO.0000000000000104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choo SW, Wee WY, Ngeow YF, Mitchell W, Tan JL, Wong GJ, et al. Genomic reconnaissance of clinical isolates of emerging human pathogen Mycobacterium abscessus reveals high evolutionary potential. Sci Rep. 2014;4:4061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Cho YJ, Yi H, Chun J, Cho SN, Daley CL, Koh WJ, et al. The genome sequence of ‘Mycobacterium massiliense’ strain CIP 108297 suggests the independent taxonomic status of the Mycobacterium abscessus complex at the subspecies level. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e81560. 10.1371/journal.pone.0081560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sassi M, Drancourt M. Genome analysis reveals three genomospecies in Mycobacterium abscessus. BMC Genomics. 2014;15:359. 10.1186/1471-2164-15-359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heydari H, Wee WY, Lokanathan N, Hari R, Mohamed Yusoff A, Beh CY, et al. MabsBase: a Mycobacterium abscessus genome and annotation database. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e62443. 10.1371/journal.pone.0062443 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Teng SH, Chen CM, Lee MR, Lee TF, Chien KY, Teng LJ, et al. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization–time of flight mass spectrometry can accurately differentiate between Mycobacterium masilliense (M. abscessus subspecies bolletti) and M. abscessus (sensu stricto). J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:3113–6. 10.1128/JCM.01239-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prevots DR, Shaw PA, Strickland D, Jackson LA, Raebel MA, Blosky MA, et al. Nontuberculous mycobacterial lung disease prevalence at four integrated health care delivery systems. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;182:970–6. 10.1164/rccm.201002-0310OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee MR, Yang CY, Chang KP, Keng LT, Yen DH, Wang JY, et al. Factors associated with lung function decline in patients with non-tuberculous mycobacterial pulmonary disease. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e58214. 10.1371/journal.pone.0058214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levy I, Grisaru-Soen G, Lerner-Geva L, Kerem E, Blau H, Bentur L, et al. Multicenter cross-sectional study of nontuberculous mycobacterial infections among cystic fibrosis patients, Israel. Emerg Infect Dis. 2008;14:378–84. 10.3201/eid1403.061405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jeon K, Kwon OJ, Lee NY, Kim BJ, Kook YH, Lee SH, et al. Antibiotic treatment of Mycobacterium abscessus lung disease: a retrospective analysis of 65 patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:896–902 . 10.1164/rccm.200905-0704OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jarand J, Levin A, Zhang L, Huitt G, Mitchell JD, Daley CL. Clinical and microbiologic outcomes in patients receiving treatment for Mycobacterium abscessus pulmonary disease. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:565–71. 10.1093/cid/ciq237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Koh WJ, Jeon K, Lee NY, Kim BJ, Kook YH, Lee SH, et al. Clinical significance of differentiation of Mycobacterium massiliense from Mycobacterium abscessus. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;183:405–10. 10.1164/rccm.201003-0395OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kothavade RJ, Dhurat RS, Mishra SN, Kothavade UR. Clinical and laboratory aspects of the diagnosis and management of cutaneous and subcutaneous infections caused by rapidly growing mycobacteria. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis. 2013;32:161–88 . 10.1007/s10096-012-1766-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakanaga K, Hoshino Y, Era Y, Matsumoto K, Kanazawa Y, Tomita A, et al. Multiple cases of cutaneous Mycobacterium massiliense infection in a “hot spa” in Japan. J Clin Microbiol. 2011;49:613–7. 10.1128/JCM.00817-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee MR, Cheng A, Lee YC, Yang CY, Lai CC, Huang YT, et al. CNS infections caused by Mycobacterium abscessus complex: clinical features and antimicrobial susceptibilities of isolates. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2012;67:222–5. 10.1093/jac/dkr420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shields RK, Clancy CJ, Minces LR, Shigemura N, Kwak EJ, Silveira FP, et al. Epidemiology and outcomes of deep surgical site infections following lung transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:2137–45. 10.1111/ajt.12292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Browne SK, Burbelo PD, Chetchotisakd P, Suputtamongkol Y, Kiertiburanakul S, Shaw PA, et al. Adult-onset immunodeficiency in Thailand and Taiwan. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:725–34. 10.1056/NEJMoa1111160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.El Helou G, Viola GM, Hachem R, Han XY, Raad II. Rapidly growing mycobacterial bloodstream infections. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:166–74. 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70316-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.El Helou G, Hachem R, Viola GM, El Zakhem A, Chaftari AM, Jiang Y, et al. Management of rapidly growing mycobacterial bacteremia in cancer patients. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;56:843–6. 10.1093/cid/cis1032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lee MR, Ko JC, Liang SK, Lee SW, Yen DH, Hsueh PR. Bacteraemia caused by Mycobacterium abscessus subsp. abscessus and M. abscessus subsp. bolletii: clinical features and susceptibilities of the isolates. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2014;43:438–41. 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2014.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Girgis DO, Karp CL, Miller D. Ocular infections caused by non-tuberculous mycobacteria: update on epidemiology and management. Clin Experiment Ophthalmol. 2012;40:467–75. 10.1111/j.1442-9071.2011.02679.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Moorthy RS, Valluri S, Rao NA. Nontuberculous mycobacterial ocular and adnexal infections. Surv Ophthalmol. 2012;57:202–35. 10.1016/j.survophthal.2011.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu R, To KK, Teng JL, Choi GK, Mok KY, Law KI, et al. Mycobacterium abscessus bacteremia after receipt of intravenous infusate of cytokine-induced killer cell therapy for body beautification and health boosting. Clin Infect Dis. 2013;57:981–91. 10.1093/cid/cit443 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bryant JM, Grogono DM, Greaves D, Foweraker J, Roddick I, Inns T, et al. Whole-genome sequencing to identify transmission of Mycobacterium abscessus between patients with cystic fibrosis: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2013;381:1551–60. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60632-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Viana-Niero C, Lima KV, Lopes ML, Rabello MC, Marsola LR, Brilhante VC, et al. Molecular characterization of Mycobacterium massiliense and Mycobacterium bolletii in isolates collected from outbreaks of infections after laparoscopic surgeries and cosmetic procedures. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:850–5. 10.1128/JCM.02052-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI). Susceptibility testing of mycobacteria, nocardiae, and other aerobic actinomycetes. Approved standard—second edition. CLSI document M24–A2. Wayne (PA): The Institute; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Adékambi T, Drancourt M. Mycobacterium bolletii respiratory infections. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:302–5. 10.3201/eid1502.080837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lee SH, Yoo HK, Kim SH, Koh WJ, Kim CK, Park YK, et al. The drug resistance profile of Mycobacterium abscessus group strains from Korea. Ann Lab Med. 2014;34:31–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Huang YC, Liu MF, Shen GH, Lin CF, Kao CC, Liu PY, et al. Clinical outcome of Mycobacterium abscessus infection and antimicrobial susceptibility testing. J Microbiol Immunol Infect. 2010;43:401–6. 10.1016/S1684-1182(10)60063-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown-Elliott BA, Mann LB, Hail D, Whitney C, Wallace RJ Jr. Antimicrobial susceptibility of nontuberculous mycobacteria from eye infections. Cornea. 2012;31:900–6. 10.1097/ICO.0b013e31823f8bb9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Broda A, Jebbari H, Beaton K, Mitchell S, Drobniewski F. Comparative drug resistance of Mycobacterium abscessus and M. chelonae isolates from patients with and without cystic fibrosis in the United Kingdom. J Clin Microbiol. 2013;51:217–23. 10.1128/JCM.02260-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhuo FL, Sun ZG, Li CY, Liu ZH, Cai L, Zhou C, et al. Clinical isolates of Mycobacterium abscessus in Guangzhou area most possibly from the environmental infection showed variable susceptibility. Chin Med J (Engl). 2013;126:1878–83 . [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nash KA, Brown-Elliott BA, Wallace RJ Jr. A novel gene, erm(41), confers inducible macrolide resistance to clinical isolates of Mycobacterium abscessus but is absent from Mycobacterium chelonae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2009;53:1367–76. 10.1128/AAC.01275-08 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Thomson RM, Carter R, Tolson C, Coulter C, Huygens F, Hargreaves M. Factors associated with the isolation of nontuberculous mycobacteria (NTM) from a large municipal water system in Brisbane, Australia. BMC Microbiol. 2013;13:89. 10.1186/1471-2180-13-89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]