Abstract

Background

No systematic review of prevention of mother to child transmission (PMTCT) in China has been performed. We aimed to estimate the uptake of PMTCT programs services in China.

Methods

We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, China National Knowledge Infrastructure, Chinese Biomedical Literature Database, and Wanfang (Chinese) to identify research studies. Only descriptive epidemiological studies were eligible for this study.

Results

A total of 57 eligible cross-section studies were finally included. We estimated that the mean HIV-positive rate of exposed infants was 4.4% (95% CI = 3.2–5.5), and more than 33% of exposed infants had not undergone HIV diagnostic testing. The percentage of initiating antiretroviral therapy (ART) in HIV-positive women was 71.0% (95% CI = 66.3–75.8), and that for initiating antiretroviral prophylaxis (ARP) in exposed infants was 78.3% (95% CI = 74.9–81.8); also, 31.3% (95% CI = 15.5–47.0) of women with HIV and < 1% of exposed infants received the combination of three antiretroviral drugs. There were bigger gap of uptake of PMTCT programs between income levels, and cities with a low income level had a higher percentage of initiating ART in HIV-positive women (80%) and ARP in exposed infants (85%) compared to cities with high-middle income (57% and 65%, respectively) (P<0.05).

Conclusions

This paper highlights the need to further scale up PMTCT services in China, especially in regions with the lowest coverage, so that more women can access and utilize them. However, some estimated outcome should be interpreted with caution due to the high level of heterogeneity and the small number of studies.

Introduction

Globally, approximately 34 million people were HIV-positive in 2011, including 3.3 million children younger than 15 years old, and of these children, 330,000 became newly infected with HIV in 2011, over 90% of them by vertical transmission[1,2]. Prompt implementation of effective prevention of mother-to-child transmission(PMTCT) of HIV programs helped prevent more than 800,000 children from becoming newly infected between 2005 and the end of 2012[3].Mother-to-child transmission (MTCT) rates in the developed regions have decreased to 1% or less due to widespread scale up of PMTCT of HIV programs[4]. The first case of an infant infected with HIV by vertical transmission in China was reported in 1995; afterwards, the MTCT rate rapidly increased to 0.4% in 2002. The Chinese ministry of health launched a PMTCT program in China in 2003 [5]. In 2004, the Chinese ministry of health issued a guideline on PMCTC that included HIV counseling and testing services, highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), elective cesarean section, and avoiding breastfeeding[6]. It is estimated that more than 780,000 people were living with HIV at the end of 2011 in China; 28.6% were women and 1.1% were children infected through MTCT[7].

Over the past 10 years, substantial progress has been made in the implementation of PMTCT interventions in China. PMTCT strategic vision 2010–2015, published by the World Health Organization (WHO), emphasized tracking program performance and its impact on the MTCT rates and on maternal and child health[8]. However, studies that were conducted to track the progress of the programs were insufficient, and a systematic review on the uptake of these programs has not been performed in China.

Only descriptive epidemiological studies that provide data regarding PMTCT interventions programs were eligible for this study. The goal of this systematic review is to provide an overview and pooled prevalence estimate of HIV-positive among pregnant women and exposed infants in China. We also provide an overview and pooled uptake estimate of some important PMTCT interventions programs including voluntary HIV counseling and testing, antiretroviral therapy and prophylaxis in pregnant women and infants, HIV-diagnosis of the exposed infants, termination of pregnancy, elective cesarean section and artificial feeding in China. In addition, we also provide a simple analysis of several trends and distributions available from the data in order to provide more insight into better treatment and control of MTCT of HIV in China.

Methods

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

We searched Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), MEDLINE, EMBASE, China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI), Chinese Biomedical Literature Database (CBM), and Wanfang (Chinese) to identify research studies that described the uptake of PMTCT programs in China.Details on search terms can be found in the S1 Appendix. The same search strategies were used with each database.We placed no language restrictions on the searches or search results. Additional strategies included hand searches of journals that were not indexed in the electronic sources, web-based searches, and screening of reference lists of retrieved studies for additional potentially relevant articles.

Only descriptive epidemiological studies were eligible for this study. When a study reported the results from different subpopulations, we treated them independently. We excluded meetings, literature reviews, discussions, editorials, research overviews, book reviews, letters, and news articles. We excluded qualitative studies, modeling studies, studies where uptake of PMTCT was assessed by interview, and cost-effectiveness studies. We excluded studies that did not provide useable data. Studies with fewer than 30 participants were excluded to improve the efficiency of the analysis.

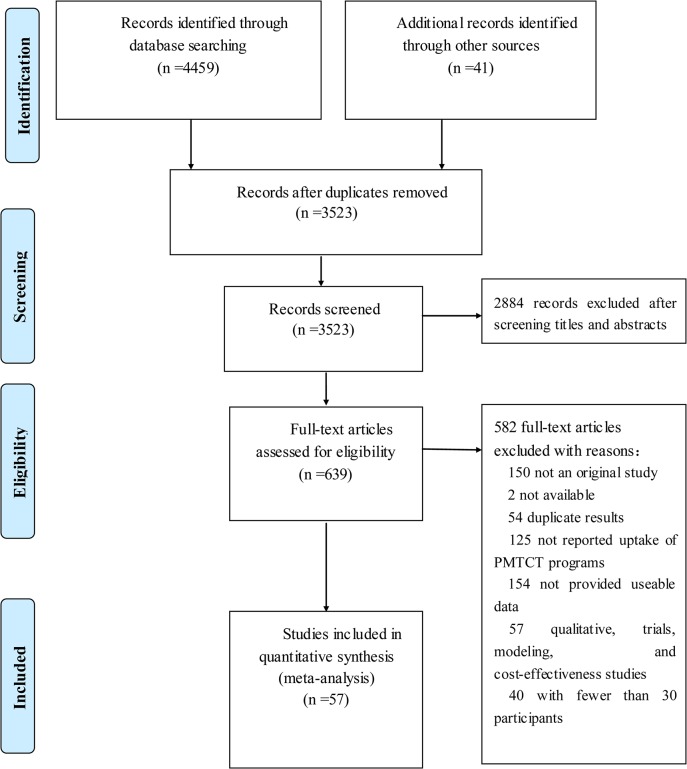

Two of the authors (MJ and HZ)independently screened the titles and abstracts of all identified studies. Studies that appeared to be relevant were selected, and the same two reviewers (MJ and HZ)independently assessed the full-text versions. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or the involvement of a third reviewer(ZH). Fig 1 shows the flowchart for selecting articles[9–65].

Fig 1. Prisma 2009 Flow diagram literature search and study selection.

PRISMA diagram showing the different steps of systematic review, starting from literature search to study selection and exclusion. At each step, the reasons for exclusion are indicated.doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0052562.g001).

Data Collection

We developed and modified a data abstraction form after a training exercise for investigators. We extracted the following data from the eligible studies: characteristics of the studies (years, design, ART regimen, and regions), participants (age, sex, and the status of HIV infection), and primary and second outcomes. We also gathered data on potential explanatory variables (i.e., variables that might explain the variance in uptake of PMTCT; Table 1). We also obtained data from the website of the Chinese administrative region; these data were used to categorize regions into regions (EasternChina, south-central China, northChina, northwestChina, southwestern China, northeastChina, and special district of Taiwan, Hongkong, and Macao) and gross domestic product in $US per head in 2013 (low income (<5520), low-middle income (5635–6750), high-middle income (6892–9961), and high income (>10915))[66,67].

Table 1. Characteristics of Studies Included in the Meta-Analysis.

| Study, year | Province | Region | Income level$ | Study design | Sample | Outcomes# | Scores of study quality& |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wang Q, 2006 | Sinkiang, Yunnan | Trans-reginoal | Low income | cross-sectional | 774 | 2, 3 | 6 |

| Zhang SW, 2012 | Anhui | Eastern China | Low income | cross-sectional | 642059 | 1,2,3, | 6 |

| Wang QF, 2011 | Yunnan | Southwestern China | Low income | cross-sectional | 78681 | 1,3,4,5,10 | 4 |

| Tan YM, 2013 | Guangxi | South-central China | Low income | cross-sectional | 363817 | 1,2,3 | 4 |

| Yang M, 2011 | Guizhou | Southwestern China | Low income | cross-sectional | 214 | 4, 10 | 5 |

| Ma 5, 2010 | Henan | South-central China | Low income | cross-sectional | 36 | 4,5,10 | 4 |

| Wu M, 2011 | Hunan | South-central China | Low-middle income | cross-sectional | 1223557 | 1, 3, 4,6,7, 10 | 5 |

| Du M, 2006 | Yunnan | Southwestern China | Low income | cross-sectional | 9145 | 1,2,3 | 4 |

| Ma Q, 2012 | Yunnan | Southwestern China | Low income | cross-sectional | 204687 | 1,2,3,5,6,7,9 | 4 |

| Huang S, 2013 | Guangdong | South-central China | High-middle income | cross-sectional | 88 | 5 | 5 |

| Cheng WM, 2009 | Henan | South-central China | Low income | cross-sectional | 363491 | 1,3,4,5,7, 9 | 8 |

| Li T, 2012 | Sichuan | Southwestern China | Low income | cross-sectional | 152 | 4,5,6,7, 8, 9, 10 | 6 |

| Wang Q,2011 | Yunnan | Southwestern China | Low income | cross-sectional | 29095 | 1,3, 4,5, 7, 9, 10 | 7 |

| Chen Y, 2013 | Sinkiang | Northwest China | Low-middle income | cross-sectional | 326030 | 1, 3,9 | 4 |

| Bai Y, 2012 | Guangxi | South-central China | Low-middle income | cross-sectional | 50043 | 1,3,4,5,7,10 | 7 |

| Cheng WM, 2006 | Henan | South-central China | Low income | cross-sectional | 31 | 4,5,7,9,10 | 4 |

| Chen ZY, 2010 | Henan | South-central China | Low income | cross-sectional | 773928 | 1,3,5 | 6 |

| Lu QC, 2008 | Henan | South-central China | Low income | cross-sectional | 171490 | 1,5,7,8, 9,10 | 6 |

| Sun DY, 2008 | Henan | South-central China | Low income | cross-sectional | 763514 | 1,4,5,7, 9, 10 | 7 |

| Wang XY, 2013 | Sichuan, Yunnan, Sinkiang, | Trans-reginoal | Low income | cross-sectional | 41586 | 1,3 | 8 |

| Dai GH, 2010 | Hubei | South-central China | High-middle income | cross-sectional | 2288933 | 1, 4, 5, 6,7,8,9,10 | 7 |

| Gong SY, 2007 | Henan, Guangxi, Sinkiang,Yunnan | Trans-reginoal | Low income | cross-sectional | 346 | 4,5,6,7,9 | 6 |

| Hong Y, 2009 | Yunnan | Southwestern China | Low income | cross-sectional | 76994 | 2,3, 4,6,7,10 | 6 |

| Li Y, 2012 | Guizhou | Southwestern China | Low income | cross-sectional | 325888 | 1,2,3,4, 5,6,7,8,9,10 | 7 |

| Wang AL, 2006 | Unclear | unclear | unclear | cross-sectional | 40 | 4,5,7,10 | 4 |

| Wang Q, 2012 | Yunnan | Southwestern China | Low income | cross-sectional | 90 | 4,7,8,9,10 | 6 |

| Wang Q, 2009 | Yunnan | Southwestern China | Low income | cross-sectional | 15596 | 1,4, 5, 7, 8,9,10 | 6 |

| Wang ZZ, 2007 | Guangdong | South-central China | High-middle income | cross-sectional | 746366 | 1,2,5,6, 7,10 | 8 |

| Xiong YH, 2010 | Yunnan | Southwestern China | Low income | cross-sectional | 102068 | 1,4,5,7,10 | 5 |

| Yang M, 2014 | Guizhou | Southwestern China | Low income | cross-sectional | 616783 | 1,4,8 | 8 |

| Zhang XH, 2009 | Zhejiang | Eastern China | High income | cross-sectional | 140 | 4,5,7,10 | 6 |

| Zhu XX, 2005 | Yunnan | Southwestern China | Low income | cross-sectional | 6440 | 1,4,5,7,10 | 5 |

| Wang XY, 2010 | Unclear | Trans-reginoal | Low income | cross-sectional | 480 | 4,6,10 | 6 |

| Wang Q, 2013 | Henan, Guangxi, Sinkiang,Yunnan | Trans-reginoal | Low income | cross-sectional | 1166 | 6 | 8 |

| Wang WM, 2008 | Henan | South-central China | Low income | cross-sectional | 143 | 4,5,6,7,8,9,10 | 4 |

| AilikaShawuli, 2013 | Sinkiang | Northwest China | Low-middle income | cross-sectional | 1303 | 4,10 | 6 |

| Wang Q, 2013 | Henan, Guangxi, Sinkiang,Yunnan,Gui | Trans-reginoal | Low income | Cohort study | 1414 | 4,10 | 8 |

| Jiang W, 2013 | Guangxi | South-central China | Low income | cross-sectional | 317 | 5 | 6 |

| Wang YX, 2011 | Guangdong | South-central China | High-middle income | cross-sectional | 172669 | 1,4,5,7,8,9,10 | 6 |

| Chen L, 2013 | Guangxi | South-central China | Low income | cross-sectional | 94454 | 1,3,4,5,10 | 6 |

| Weng YQ, 2010 | Guangxi | South-central China | Low income | cross-sectional | 42626 | 1,2,3,4,5,7,10 | 8 |

| Wen Y, 2011 | Yunnan | Southwestern China | Low income | cross-sectional | 57096 | 1,2,3,5,6,8,9,10 | 6 |

| Cao YZ,2011 | Guangdong | South-central China | High-middle income | cross-sectional | 412525 | 3,5 | 5 |

| Zhang HY, 2011 | Chongqing | Southwestern China | High-middle income | cross-sectional | 68 | 4,5,7,10 | 4 |

| Zhou FR, 2010 | Shandong | Eastern China | High-middle income | cross-sectional | 118625 | 2,3 | 7 |

| An FL, 2009 | Henan | South-central China | Low income | cross-sectional | 62028 | 1,5,7,9,10 | 6 |

| Feng L, 2013 | Chongqing | Southwestern China | High-middle income | cross-sectional | 1789 | 1,3 | 8 |

| Liang K, 2011 | Hubei, Hebei, Shanxi, Sinkiang | Trans-reginoal | low-middle income | cross-sectional | 421 | 5 | 5 |

| Wang FK, 2009 | Henan | South-central China | Low income | cross-sectional | 339866 | 1,4,5,7,8,9 | 5 |

| Fang LW, 2010 | Cover 31 provinces | Trans-reginoal | cross-sectional | 10360655 | 2,3,4,5,6,7,9,10 | 8 | |

| Luo XM, 2011 | Hunan | South-central China | Low income | cross-sectional | 98004 | 1,3 | 4 |

| Sun LD, 2011 | Yunnan | Southwestern China | Low income | cross-sectional | 30101 | 1,3,4,5,8 | 6 |

| Jia LQ, 2010 | Yunnan | Southwestern China | Low income | cross-sectional | 17425 | 1,2,3,4,5,7,8,9,10 | 6 |

| Li B, 2013 | Guangdong | South-central China | High-middle income | cross-sectional | 108 | 4,6,7,10 | 8 |

| Song JM, 2013 | Guangdong | South-central China | High-middle income | cross-sectional | 1843122 | 1,3,4,5,10 | 8 |

| Lin AW, 2014 | Hong Kong | High income | cross-sectional | 489187 | 1,3,4,5,6 | 8 | |

| Zhao XH, 2013 | Zhejiang | Eastern China | High income | cross-sectional | 4359246 | 1,2,3,4,10 | 8 |

Note

# The primary outcomes for pregnant women were the following: (1) HIV-positive rate; (2) underwent voluntary HIV-counseling; (3) underwent voluntary HIV-testing; (4) initiating antiretroviral therapy (ART); (5) selecting termination of pregnancy; (6) elective cesarean section; and (7) artificialfeeding. The primary outcomes for children were the following: (8) HIV-positive rate (9) HIV diagnosis of the exposed infants between 12 and 18 months by PCR or antibody test; and (10) initiating ARP in exposed infants.

& Quality score assessed by Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ)

$ Income level is divided to high income (>10915), high-middle income (6892–9961), low-middle income, low income (<5520) according to GDP (in $US per head)

For each study, one reviewer(ZD) extracted the data, a second reviewer (SZ)checked the accuracy, and a third reviewer (JH)evaluated the data for disagreements.

Primary Outcomes

The primary outcomes for pregnant women were the following: (1) HIV-positive ratein the present pregnancy (including antenatal, intrapartum, and postpartum); (2) underwent voluntary HIV-counselingin the present pregnancy (including antenatal, intrapartum, and postpartum); (3) underwent voluntary HIV-testingin the present pregnancy (including antenatal, intrapartum, and postpartum); (4) initiating antiretroviral therapy (ART) from 28 weeks of pregnancy (5) selecting termination of pregnancy; (6) elective cesarean section; and (7) artificialfeeding. The primary outcomes for children were the following: (8) HIV-positive rate (9) HIV diagnosis of the exposed infants between 12 and 18 months by PCR or antibody test; and (10) initiating ARP in exposed infantsin the first 72 hours after delivery.

Quality assessment

The quality of eligible literature was assessed according to the criteria of observational studies in recommended by Agency of Healthcare Research and Quality AHRQ included 11-items with a yes/no/unclear response option: the “Yes” would be scored “1”, “No” or “unclear” was scored “0”. Articles were scored as follows: low quality (0–3), moderate quality (4–7), high quality (8–11) [68].

Statistical Analysis

We calculated the pooled rate or percentage with 95% CIs with a random effect model (DerSimonian–Laird’s method)[69]. We used the Q-statistic and I2 statistic to estimate the heterogeneity between studies, and we used “small,” “moderate” and “large” to describe values of 25%, 50% and 75% for the I2[70–71].

We investigated potential sources of heterogeneity with subgroup analyses. In subgroup analyses, we estimated the uptake of PMTCT according to regions (EasternChina, southChina, South-central China, northChina, northwest China, southwestern China, northeastChina, and special district of Taiwan Hongkong and Macao), per capita GDP (low income, low-middle income, high-middle income, and high income), pregnancy stage (premarital checkups, antenatal care, and at delivery), and antiretroviral therapy regimens (single regimen vs. combination regimens).

To establish the robustness of the outcome by sensitivity analyses, we applied a fixed effects model;used the trim-and-fill method; and excluded studies with a low number of participants [72].A funnel plot was used to explore the publication bias. Funnel-plot asymmetry was further assessed by the method of Begg’ test and the modified Egger’s linear regression test[73].We performed all analyses using the software STATA (version 11.0).

Results

Characteristics of Eligible Studies

We identified 4459papers from a database search, 28 papers through internet and hand searches, and 15 papers through checking reference lists. No unpublished data that met our inclusion criteria were identified. During the step of screening the abstracts, 2884 papers were excluded, leaving 639full text papers that were assessed for eligibility. We excluded 40 papers with fewer than 30 participants; in the end, a total of 57 papers fulfilled our inclusion criteria and were included in the meta-analysis (Fig 1). These 57 studies originated from 31 of 34 provinces in China. Table 1 presents the characteristics of every analysis outcome, 13 studies were of high quality, and other studies were of moderate quality.

Estimated HIV-positive rate

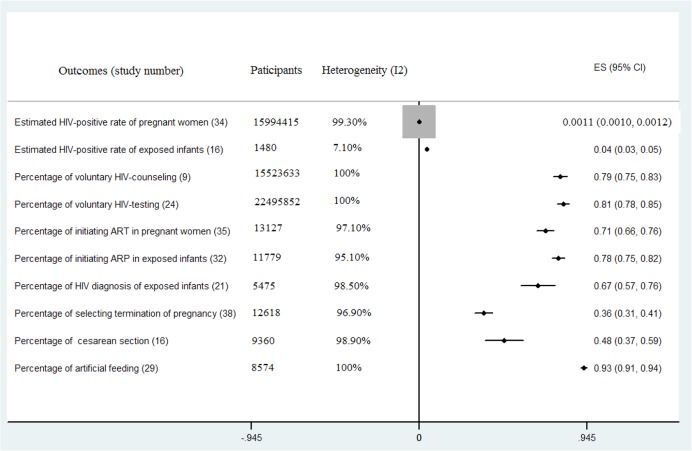

Thirty-four studies, including 15,994,415 pregnant women, reported the HIV-positive rate of pregnant women (Fig 2). We estimated that the mean HIV-positive rate of pregnant women was 0.11% (95% CI = 0.1–0.12) with a high level of heterogeneity between the rate estimates (Q = 5049.43, P<0.001; I2 = 99.30%). Sixteen studies, including 1,480 infants, reported the HIV-positive rate of exposed infants. We estimated that the mean HIV-positive rate of exposed infants was 4.4% (95% CI = 3.2–5.5) with a low level of heterogeneity between the rate estimates (Q = 13.96, P = 0.602; I2 = 7.10%) (Fig 2 and Table 2).

Fig 2. Meta-Analyses of Uptake of Prevention of Mother-to-Child-Transmission (PMTCT) in China.

ART = antiretroviral therapy; ARP = antiretroviral prophylaxis; ES refer to rate /percentage.

Table 2. Egger’s linear regression test and Begg's test to measure the funnel plot asymmetric.

| Outcome | Heterogeneity | Egg's test | Begg's test | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Q | p | I2(%) | t | P | z | p | |

| Estimated HIV-positive rate of pregnant women | 5049.93 | <0.001 | 99.3 | 6.63 | 0 | 2.98 | 0.003 |

| Estimated HIV-positive rate of exposed infants | 13.96 | 0.602 | 7.1 | 1.77 | 0.077 | 2.05 | 0.058 |

| Percentage of voluntary HIV-counseling | 320000 | <0.001 | 100 | -0.5 | 0.628 | 0.09 | 0.929 |

| Percentage of voluntary HIV-testing | 160000 | <0.001 | 100 | -1.25 | 0.222 | -1.61 | 0.108 |

| Percentage of initiating ART in HIV-positive women | 1335.82 | <0.001 | 97.1 | -0.7 | 0.486 | -2.25 | 0.025 |

| Percentage of initiating ARP in exposed infants | 617.39 | <0.001 | 95.1 | -2.58 | 0.031 | -3 | 0.003 |

| Percentage of HIV diagnosis of the exposed infants | 970.78 | <0.001 | 98.5 | -1.67 | 0.096 | -0.62 | 0.545 |

| Percentage of selecting termination of pregnancy | 12909.6 | <0.001 | 96.9 | 1.68 | 0.101 | 0.94 | 0.346 |

| Percentage of cesarean section | 1370.5 | <0.001 | 98.9 | 0.16 | 0.874 | 0.81 | 0.418 |

| Percentage of artificial feeding | 1255.5 | <0.001 | 100 | -0.94 | 0.358 | -2.98 | 0.003 |

Estimated Uptake of PMTCT Programs Services

The estimated percentages of voluntary HIV-counseling and HIV-testing of pregnant women were 79.3% (95% CI = 75.4–83.3) and 81.2% (95% CI = 77.8–84.6), respectively. The studies were very heterogeneous in both of the analyses (Fig 2). We identified 35 studies providing data for the percentage of initiating ART in HIV-positive women and 32 studies providing data for the percentage of initiating ARP in exposed infants. We estimated that the percentage of initiating ART in HIV-positive women was 71.0% (95% CI = 66.3–75.8) and initiating ARP in exposed infants was 78.3% (95% CI = 74.9–81.8); these estimates were also associated with a high level of heterogeneity (Fig 2).Other outcomes were also estimated, and the results are displayed in Fig 2.

Subgroup Analyses of the Uptake of PMTCT Programs

Table 3 and Table 4 present the variation in the uptake of PMTCT programs according to years. No study on PMTCT programs in China was reported in China before 2004. The time trends for the HIV-positive rate of pregnant were reported in 34 studies from 2000–2012; the mean estimated rate was not significantly changed since 2000. However, time trends for the HIV-positive rate of exposed infants were estimated for only 3 low income regions from 2005–2012; the mean estimated rate in these regions for 2005 was 11.8% (95% CI = 0–27.1) compared with 6.1% (95% CI = 2.7–9.4)in 2010. The estimated percentages of initiating ART in HIV-positive women and initiating ARP in exposed infants were continually increased, and the mean estimated percentage of initiating ART in HIV-positive women increased from 64.6% (95% CI = 60.7–68.6)in 2005 to 79.5% (95% CI = 76.0–83.1)in 2012, while initiating ARP in exposed infants increased from 77.2%(95% CI = 73.6–80.7)in 2005 to 91.6%(95% CI = 87.5–95.6) in 2010. The estimated percentage of voluntary HIV-testing and HIV diagnosis of the exposed infants has continually increased to 100% since 2004, while voluntary HIV-counseling has not obviously changed. Interestingly, the estimated percentage of selecting termination of pregnancy decreased from 40% (95% CI = 9.6–70.4)in 2003 to 15.8%(95% CI = 0–32.2)in 2011; the estimated percentage of artificial feeding was not obviously changed.

Table 3. Subgroup Analyses of Uptake of Prevention of Mother-to-Child-Transmission (PMTCT) from 2004 to 2007.

| Outcomes | Before 2004 | 2004 | 2005 | 2006 | 2007 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies | Rate(95%CI) | Studies | Rate(95%CI) | Studies | Rate(95%CI) | Studies | Rate(95%CI) | Studies | Rate(95%CI) | |

| HIV-positive rate of pregnant women (%) | 12 | 0.1(0.00–0.1) | 8 | 0.10(0.06–0.14) | 13 | 0.01(0.01–0.02) | 15 | 0.11(0.09–0.14) | 14 | 0.12(0.10–0.14) |

| HIV-positive rate of exposed infants | - | - | - | - | 1 | 0.12(0–0.27) | 3 | 0.08(0–0.17) | 3 | 0.13(0.05–0.22) |

| Voluntary HIV-counseling | - | - | 1 | 0.81(0.79–0.82) | 2 | 0.81(0.59–1.00) | 2 | 0.9(0.79–1.00) | 2 | 0.88(0.82–0.93) |

| Voluntary HIV-testing | - | - | 5 | 0.58(0.21–0.95) | 8 | 0.63(0.48–0.78) | 9 | 0.72(0.65–0.79) | 9 | 0.81(0.76–0.85) |

| Initiating ART in HIV-positive women | - | - | - | - | 1 | 0.65(0.61–0.69) | 1 | 0.67(0.64–0.70) | 1 | 0.67(0.64–0.69) |

| Initiating ARP in exposed infants | - | - | - | - | 1 | 0.77(0.74–0.81) | 1 | 0.80(0.78–0.83) | 1 | 0.84(0.82–0.86) |

| HIV diagnosis of the exposed infants | - | - | - | - | 1 | 0.81(0.64–0.98) | 3 | 0.86(0.82–0.89) | 3 | 0.76(0.73–0.79) |

| Selecting termination of pregnancy | 2 | 0.4(0.10–0.70) | 3 | 0.25(0.07–0.43) | 8 | 0.28(0.22–0.34) | 7 | 0.37(0.30–0.45) | 6 | 0.36(0.27–0.44) |

| Cesarean section | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Artificial feeding | - | - | - | - | 2 | 0.87(0.85–0.90) | 2 | 0.82(0.58–1.00) | 2 | 0.92(0.90–0.93) |

Note: ARP = antiretroviral prophylaxis; ART = antiretroviral therapy

Table 4. Subgroup Analyses of Uptake of Prevention of Mother-to-Child-Transmission (PMTCT) from 2008 to 2012.

| Outcomes | 2008 | 2009 | 2010 | 2011 | 2012 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies | Rate(95%CI) | Studies | Rate(95%CI) | Studies | Rate(95%CI) | Studies | Rate(95%CI) | Studies | Rate(95%CI) | |

| HIV-positive rate of pregnant women (%) | 14 | 0.10(0.08–0.12) | 13 | 0.07(0.01–0.12) | 13 | 0.09(0.07–0.10) | 5 | 0.10(0.06–0.14) | 3 | 0.15(0.01 to 0.28) |

| HIV-positive rate of exposed infants | 3 | 0.06(0.01–0.10) | 2 | 0.04(0.00–0.08) | 2 | 0.04(0.00–0.08) | 2 | 0.03(0.00–0.05) | 2 | 0.06(0.03–0.09) |

| Voluntary HIV-counseling | 3 | 0.88(0.76–0.99) | 3 | 0.80(0.76–0.84) | 2 | 0.64(0.64–0.65) | 1 | 0.83(0.83–0.84) | - | - |

| Voluntary HIV-testing | 10 | 0.76(0.71–0.82) | 8 | 0.77(0.71–0.83) | 6 | 0.81(0.68–0.93) | 4 | 0.95(0.90–0.99) | 3 | 0.99(0.97–1.00) |

| Initiating ART in HIV-positive women | 1 | 0.74(0.72–0.77) | 2 | 0.71(0.52–0.90) | 4 | 0.79(0.72–0.86) | 1 | 0.75(0.64–0.86) | 1 | 0.80(0.76–0.83) |

| Initiating ARP in exposed infants | 2 | 0.83(0.69–0.97) | 1 | 0.83(0.81–0.84) | 2 | 0.92(0.88–0.96) | - | - | - | - |

| HIV diagnosis of the exposed infants | 3 | 0.74(0.72–0.77) | 2 | 0.73(0.70–0.76) | 1 | 0.82(0.75–0.89) | 1 | 0.99(0.98–1.00) | 1 | 0.98(0.95–1.00) |

| Selecting termination of pregnancy | 6 | 0.31(0.22–0.41) | 4 | 0.24(0.14–0.35) | 3 | 0.19(0.09–0.28) | 1 | 0.16(0–0.32) | - | - |

| Cesarean section | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Artificial feeding | 3 | 0.91(0.84–0.99) | 1 | 0.94(0.93–0.95) | 1 | 0.81(0.73–0.89) | - | - | - | - |

Note: ARP = antiretroviral prophylaxis; ART = antiretroviral therapy

The uptake of PMTCT programs varied widely between regions (Table 5). The region with the highest HIV-positive rate of pregnant women was the Xinjiang Uygur [Uighur] autonomous region (0.41%, 95% CI = 0.38–0.44) in northwest China, but only one study included that region in its estimate. The rates in eastern China (0.02%, 95% CI = 0.01–0.02) and south-central China (0.06%, 95% CI = 0.05–0.07) were all less than 0.1% (Table 4). At a provincial level, the estimated voluntary HIV-testing rate ranged from approximately 44.3% (95% CI = 20.4–68.2) in several northwest regions to 79.0%(95% CI = 75.3–82.4)in both south-central China and southwestern China (Table 4). Northwest China also reported the lowest percentage of voluntary HIV-counseling; the estimated mean rate was 19.8% (95% CI = 16.2%-23.5). The rates of initiating ART in HIV-positive women were the highest in northwest China (76.8%, 95% CI = 74.5–79.1), which was followed by south-central China (70.0%, 95% CI = 60.5–77.7); the lowest rates were for eastern China (49.3%, 95% CI = 19.5–79.1) (Table 5).

Table 5. Subgroup Analyses of Uptake of Prevention of Mother-to-Child-Transmission (PMTCT) by Region.

| Outcomes | Eastern China | South-central China | Northwest China | Southwestern China | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies | Rate(95%CI) | Studies | Rate(95%CI) | Studies | Rate(95%CI) | Studies | Rate(95%CI) | |

| HIV-positive rate of pregnant women(%) | 2 | 0.02(0.01–0.02) | 16 | 0.06(0.05–0.07) | 1 | 0.41(0.39–0.44) | 14 | 0.24(0.20–0.28) |

| HIV-positive rate of exposed infants | 0 | - | 5 | 0.04(0.02–0.05) | 1 | 0.06(0.04–0.08) | 7 | 0.04(0.02–0.07) |

| Voluntary HIV-counseling | 3 | 0.84(0.72–0.97) | 1 | 0.73(0.73–0.74) | 1 | 0.20(0.16–0.24) | 5 | 0.77(0.72–0.82) |

| Voluntary HIV-testing | 3 | 0.72(0.51–0.93) | 7 | 0.79(0.71–0.87) | 3 | 0.44(0.20–0.68) | 11 | 0.79(0.75–0.82) |

| Initiating ART in HIV-positive women | 2 | 0.49(0.20–0.79) | 13 | 0.70(0.56–0.84) | 1 | 0.77(0.75–0.79) | 13 | 0.69(0.61–0.78) |

| Initiating ARP in exposed infants | 2 | 0.66(0.50–0.82) | 14 | 0.78(0.68–0.87) | 1 | 0.83(0.80–0.85) | 11 | 0.75(0.66–0.84) |

| HIV diagnosis of the exposed infants | 0 | - | 7 | 0.67(0.53–0.81) | 1 | 0.87(0.84–0.89) | 6 | 0.69(0.38–1.00) |

| Selecting termination of pregnancy | 1 | 0.43(0.35–0.51) | 20 | 0.41(0.32–0.50) | 0 | - | 12 | 0.31(0.21–0.42) |

| Cesarean section | 0 | - | 6 | 0.54(0.32–0.75) | 0 | - | 5 | 0.45(0.10–0.79) |

| Artificial feeding | 1 | - | 12 | 0.91(0.87–0.94) | 0 | - | 8 | 0.94(0.92–0.96) |

Note: ARP = antiretroviral prophylaxis; ART = antiretroviral therapy

The estimated HIV-positive rate of pregnant women was the highest in studies from low income regions(0.20%, 95%CI = 0.17–0.22), which was followed by low-middle income regions(0.15%, 95%CI = 0.07–0.29). Studies from high-middle income and high income regions reported the lowest prevalence(Table 5). The high income region reported the highest percentage of voluntary HIV-counseling (93.2%, 95%CI = 93.2–93.2), voluntary HIV-testing (94.9%, 95%CI = 88.8–1.00) and cesarean section (81.1%, 95%CI = 70.6–91.7), while the low income region reported the highest percentage of initiating ART in HIV-positive women (79.9%, 95%CI = 75.5–84.3) and initiating ARP in exposed infants (84.6%, 95%CI = 80.8–88.4) (Table 6).

Table 6. Subgroup Analyses of Uptake of Prevention of Mother-to-Child-Transmission (PMTCT) by Income.

| Outcomes | High income | High-middle income | Low-middle income | Low income | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies | Rate(95%CI) | Studies | Rate(95%CI) | Studies | Rate(95%CI) | Studies | Rate(95%CI) | |

| HIV-positive rate of pregnant women (%) | 2 | 0.02(0.02–0.02) | 6 | 0.02(0.01–0.02) | 3 | 0.15(0.07–0.29) | 23 | 0.20(0.17–0.22) |

| HIV-positive rate of exposed infants | 0 | - | 2 | - | 1 | 0.06(0.04–0.08) | 9 | 0.04(0.03–0.05) |

| Voluntary HIV-counseling | 1 | 0.93(0.93–0.93) | 0 | - | 1 | 0.89(0.89–0.89) | 6 | 0.86(0.78–0.94) |

| Voluntary HIV-testing | 2 | 0.95(0.89–1.00) | 4 | 0.95(0.93–0.98) | 4 | 0.64(0.49–0.78) | 12 | 0.87(0.83–0.91) |

| Initiating ART in HIV-positive women | 3 | 0.65(0.36–0.93) | 4 | 0.57(0.31–0.83) | 3 | 0.61(0.50–0.72) | 21 | 0.80(0.76–0.84) |

| Initiating ARP in exposed infants | 2 | 0.66(0.50–0.82) | 5 | 0.65(0.47–0.83) | 3 | 0.70(0.61–0.80) | 20 | 0.85(0.81–0.88) |

| HIV diagnosis of the exposed infants | 0 | - | 2 | 0.66(0.32–1.00) | 2 | 0.81(0.69–0.92) | 12 | 0.68(0.53–0.84) |

| Selecting termination of pregnancy | 2 | 0.35(0.20–0.51) | 7 | 0.45(0.36–0.53) | 3 | 0.29(0.28–0.31) | 25 | 0.35(0.27–0.43) |

| Cesarean section | 1 | 0.81(0.71–0.92) | 3 | 0.57(0.43–0.71) | 2 | 0.49(0.48–0.51) | 9 | 0.43(0.25–0.61) |

| Artificial feeding | 1 | - | 5 | 0.77(0.59–0.95) | 2 | 0.95(0.90–1.00) | 17 | 0.94(0.92–0.95) |

Note: ARP = antiretroviral prophylaxis; ART = antiretroviral therapy

We estimated that 38.6%(95% CI = 34.0–44.1) of women with HIV received ART antenatally, 35.5% (95% CI = 18.7–53.2)received ART in the intrapartum period, and 27.7% (95% CI = 0.00–75.0)received it postnatally; 47.6%(95% CI = 18.9–75.2) received single-dose nevirapine (NVP), 21.6% (95% CI = 9.1–34.8)received single-dose zidovudine (AZT), 18.9% (95% CI = 8.9–28.4)received combination of AZT and NVP, 13.4% (95% CI = 2.4–25.3)received combination of AZT and lamivudine (3TC), and 31.3%(95% CI = 16.2–47.0) received combination of three antiretroviral drugs (AZT+3TC/AZT+NVP). In addition, 46.6% (95% CI = 7.1–85.8)of exposed infants received single-dose NVP, 18.9% (95% CI = 1.0–36.3)received single-dose AZT, 53.3% (95% CI = 40.1–66.7)received a combination of AZT and NVP, and fewer than 1% (95% CI = 0.0–3.0) received the combination of three antiretroviral drugs.

Sensitivity Analyses

We used the fixed effect model and trim and fill analysis, and we excluded studies with fewer participants to perform sensitivity analyses of the uptake of PMTCT programs, which gave similar results to the primary analysis.

Meta-regression analysis, assessment of publication bias

We noted significant heterogeneity within studies(P<0.001, I2 = 95.1%–100%) except for the outcome of estimated HIV-positive rate of exposed infants (P = 0.602, I2 = 7.1). In univariate and multivariable meta-regression analyses (Table 6), we usedvariables including year of publication, sample size, regions (eastern China, south-central China, northwest China, southwestern China, and trans-regional), income level, and quality score. We notedthat regions, income level, and sample size were significantly associated with the estimated HIV-positive rate of pregnant women; year of publication was significantly associated with the percentage of voluntary HIV-testing (R2 = 25.35%, P = 0.004); year of publication (R2 = 30.63%, P = 0.056) and sample size (R2 = 38.68%, P = 0.032) were significantly associated with the percentage of voluntary HIV-counseling; income level were significantly associated with the percentage of initiating ARP in exposed infants (R2 = 12.36%, P = 0.043); year of publication was significantly associated with the percentage of selecting termination of pregnancy (R2 = 17.59%, P = 0.007). Furthermore, in multivariable analysis these variables still were significantly associated with the heterogeneity of these main outcomes (Table 6).

Egger’slinear regression test (P = 0.093) and Begg’s test (P = 0.204) shown significantpublication bias among the contributing studies in terms of the outcome of the estimated HIV-positive rate of pregnant women, the percentage of initiating ART in HIV-positive women, the percentage of initiating ARP in exposed infants, and the percentage of artificial feeding (Table 7).

Table 7. Results of Meta-regression for prevention of mother-to-child-transmission (PMTCT) of China.

| Covariate | Univariate analyses | Multivariable analyses | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coefficient (95% CI) | P value | Variance explained (%) | Coefficient (95% CI) | P value | Variance explained (%) | |

| Estimated HIV-positive rate of pregnant women | 37.03 | |||||

| Year of publication | -0.0001(-0.0006 to 0.0003) | 0.553 | -2.43 | |||

| Regions (middle south is reference) | 28.59 | |||||

| Eastern China | -0.0005(-0.0034 to 0.0023) | 0.701 | 0.0004(-0.0025 to 0.0034) | 0.771 | ||

| Northwest China | 0.0034(-0.0012 to 0.0081) | 0.147 | 0.0041 (-0.0004 to 0.0085) | 0.073 | ||

| Southwestern China | 0.0029(0.0011 to 0.0046) | 0.002 | 0.0021(0.0004 to 0.0085) | 0.002 | ||

| Income level | -0.0010(-0.0019 to-0.0001) | 0.032 | 11.51 | -0.0003(-0.0013 to 0.0006) | 0.457 | |

| Sample size (<100000 vs ≥100000) | -0.0025(-0.0042 to-0.0009) | 0.004 | 21.47 | -0.0017(-0.0034 to-0.0000) | 0.044 | |

| Quality score | -0.0002 (-0.0008 to 0.0005) | 0.625 | -2.59 | |||

| Percentage of voluntary HIV-counseling | -17 | |||||

| Year of publication | -0.014(-0.090 to 0.063) | 0.705 | -5.53 | 0.219(-0.080 to 0.518) | 0.199 | |

| Regions (middle south is reference) | -14.92 | |||||

| Northwest China | 0.211(-0.494 to 0.916) | 0.523 | 0.488(-0.749 to 1.724) | 0.382 | ||

| Southwestern China | 0.034(-0.340 to 0.408) | 0.844 | 0.597(-0.342 to 1.536) | 0.176 | ||

| Income level | 0.005(-0.214 to 0.223) | 0.964 | -0.735 | 0.248(-0.199 to 0.695) | 0.232 | |

| Sample size (<100 vs ≥100) | 0.093(-0.059 to 0.245) | 0.211 | 3.95 | 0.219(-0.080 to 0.518) | 0.127 | |

| Quality score | -0.033(-0.155 to 0.089) | 0.571 | -4.17 | 0.054 (-0.164 to 0.272) | 0.578 | |

| Percentage of voluntary HIV-testing | 29.54 | |||||

| Year of publication | 0.056(0.019 to 0.093) | 0.004 | 25.35 | 0.05(0.009 to 0.091) | 0.02 | |

| Regions (middle south is reference) | 6.41 | |||||

| Northwest China | -0.334(-0.725 to 0.057) | 0.091 | -0.282(-0.635 to 0.07) | 0.11 | ||

| Southwestern China | -0.092(-0.328 to 0.144) | 0.427 | 0.046(-0.195 to 0.287) | 0.694 | ||

| Eastern China | -0.198(-0.498 to 0.102) | 0.186 | -0.193(-0.466 to 0.079) | 0.153 | ||

| Trans-reginoal | 0.096(-0.237 to 0.429) | 0.554 | -0.037(-0.357 to 0.284) | 0.812 | ||

| Income level | 0.049(-0.05 to 0.148) | 0.318 | 0.11 | -0.021(-0.132 to 0.09) | 0.694 | |

| Sample size (<100 vs ≥100) | 0.153(-0.038 to 0.345) | 0.112 | 6.14 | 0.149(-0.074 to 0.372) | 0.177 | |

| Quality score | 0.041(-0.029 to 0.111) | 0.239 | 1.76 | 0.035(-0.038 to 0.107) | 0.327 | |

| Percentage of voluntary HIV-counseling | 99.06 | |||||

| Year of publication | 0.075(-0.003 to 0.153) | 0.056 | 30.63 | 0.034(-0.233 to 0.302) | 0.35 | |

| Regions (middle south is reference) | -11.09 | |||||

| Northwest China | -0.535(-1.718 to 0.649) | 0.298 | -0.912(-1.754 to-0.07) | 0.046 | ||

| Southwestern China | 0.025(-0.891 to 0.941) | 0.947 | -0.664(-1.395 to 0.067) | 0.055 | ||

| Eastern China | 0.112(-0.912 to 1.136) | 0.79 | -0.882(-1.84 to 0.075) | 0.054 | ||

| Trans-reginoal | 0.122(-1.06 to 1.305) | 0.801 | -0.205(-0.809 to 0.4) | 0.145 | ||

| Income level | 0.027(-0.231 to 0.285) | 0.818 | -11.77 | 0.327(0.048 to 0.606) | 0.043 | |

| Sample size (<10000 vs ≥10000) | 0.431(0.046 to 0.815) | 0.032 | 38.68 | 0.647(-0.534 to 1.828) | 0.091 | |

| Quality score | 0.016(-0.182 to 0.214) | 0.857 | -12.08 | -0.418(-0.71 to-0.125) | 0.035 | |

| Percentage of initiating ART in HIV-positive women | 8.65 | |||||

| Year of publication | 0.01(-0.023 to 0.043) | 0.554 | -2.22 | 0.043(0.001 to 0.085) | 0.043 | |

| Regions (middle south is reference) | -8.48 | |||||

| Northwest China | 0.083(-0.354 to 0.519) | 0.701 | 0.041(-0.381 to 0.462) | 0.844 | ||

| Southwestern China | 0.009(-0.166 to 0.184) | 0.918 | -0.095(-0.274 to 0.083) | 0.283 | ||

| Eastern China | -0.057(-0.288 to 0.174) | 0.618 | 0.01(-0.244 to 0.265) | 0.933 | ||

| Trans-reginoal | 0.104(-0.125 to 0.332) | 0.361 | 0.139(-0.088 to 0.366) | 0.22 | ||

| Income level | -0.063(-0.129 to 0.003) | 0.06 | -7.18 | -0.091(-0.178 to-0.003) | 0.042 | |

| Sample size (<100 vs ≥100) | -0.064(-0.204 to 0.075) | 0.353 | -0.02 | -0.112(-0.273 to 0.049) | 0.166 | |

| Quality score | -0.015(-0.069 to 0.038) | 0.563 | -2.00 | -0.02(-0.087 to 0.046) | 0.533 | |

| Percentage of initiating ARP in exposed infants | -11.63 | |||||

| Year of publication | 0.005(-0.036 to 0.046) | 0.815 | 3.94 | 0.002(-0.053 to 0.058) | 0.934 | |

| Regions (middle south is reference) | -10.39 | |||||

| Northwest China | 0.07(-0.353 to 0.493) | 0.736 | 0.058(-0.416 to 0.532) | 0.801 | ||

| Southwestern China | -0.009(-0.188 to 0.169) | 0.915 | -0.073(-0.29 to 0.145) | 0.492 | ||

| Eastern China | -0.117(-0.444 to 0.209) | 0.465 | 0.115(-0.307 to 0.536) | 0.577 | ||

| Trans-reginoal | 0.121(-0.142 to 0.384) | 0.351 | 0.047(-0.257 to 0.35) | 0.752 | ||

| Income level | -0.074(-0.145 to-0.002) | 0.043 | 12.36 | -0.108(-0.227 to 0.012) | 0.075 | |

| Sample size (<100 vs ≥100) | 0.067(-0.087 to 0.222) | 0.381 | -1.3 | 0.047(-0.146 to 0.24) | 0.616 | |

| Quality score | -0.003(-0.067 to 0.061) | 0.93 | -4.2 | -0.003(-0.089 to 0.083) | 0.935 | |

| Percentage of selecting termination of pregnancy | 23.18 | |||||

| Year of publication | -0.039(-0.066 to-0.011) | 0.007 | 17.59 | -0.05(-0.082 to-0.019) | 0.003 | |

| Regions (middle south is reference) | ||||||

| Southwestern China | -0.098(-0.242 to 0.047) | 0.179 | -1.37 | -0.042(-0.181 to 0.097) | 0.54 | |

| Eastern China | -0.061(-0.354 to 0.232) | 0.674 | -0.141(-0.459 to 0.178) | 0.373 | ||

| Trans-reginoal | -0.138(-0.377 to 0.102) | 0.251 | -0.164(-0.385 to 0.058) | 0.141 | ||

| Income level | 0.023(-0.044 to 0.091) | 0.482 | -1.35 | 0.057(-0.023 to 0.138) | 0.156 | |

| Sample size (<100 vs ≥100) | -0.1(-0.226 to 0.025) | 0.114 | 4.43 | -0.037(-0.165 to 0.091) | 0.557 | |

| Quality score | 0.009(-0.04 to 0.058) | 0.718 | -2.42 | 0.013(-0.035 to 0.061) | 0.583 | |

| Percentage of cesarean section | -41.07 | |||||

| Year of publication | 0.02(-0.052 to 0.092) | 0.555 | -4.47 | 0.018(-0.106 to 0.143) | 0.743 | |

| Regions (middle south is reference) | -2.37 | |||||

| Southwestern China | -0.088(-0.443 to 0.267) | 0.599 | 0.199(-0.748 to 1.146) | 0.641 | ||

| Eastern China | 0.276(-0.358 to 0.911) | 0.361 | -0.101(-1.436 to 1.234) | 0.866 | ||

| Trans-reginoal | -0.176(-0.552 to 0.199) | 0.327 | 0.208(-0.929 to 1.346) | 0.684 | ||

| Income level | 0.096(-0.044 to 0.237) | 0.162 | 7.96 | 0.248(-0.465 to 0.961) | 0.446 | |

| Sample size (<100 vs ≥100) | -0.149(-0.434 to 0.135) | 0.279 | 2.1 | -0.163(-0.76 to 0.434) | 0.546 | |

| Quality score | 0.016(-0.091 to 0.122) | 0.758 | -6.42 | -0.104(-0.432 to 0.224) | 0.486 | |

| Percentage of artificial feeding | -11.37 | |||||

| Year of publication | -0.011(-0.033 to 0.01) | 0.295 | -0.03 | 0.016(0.022 to 0) | -0.046 | |

| Regions (middle south is reference) | -20.67 | |||||

| Southwestern China | 0.042(-0.049 to 0.132) | 0.346 | 0.033(-0.078 to 0.144) | 0.534 | ||

| Trans-reginoal | 0.017(-0.128 to 0.161) | 0.813 | -0.055(-0.217 to 0.106) | 0.476 | ||

| Income level | -0.049(-0.104 to 0.007) | 0.081 | 8.9 | -0.042(-0.12 to 0.036) | 0.267 | |

| Sample size (<100 vs ≥100) | 0.047(-0.029 to 0.122) | 0.21 | 2.68 | 0.079(-0.013 to 0.171) | 0.088 | |

| Quality score | -0.012(-0.043 to 0.019) | 0.416 | -2.27 | 0.009(-0.03 to 0.048) | 0.644 | |

Discussion

This is the first comprehensive overview of PMTCT programs in China at the national level. We included 57 studies covering all provinces in China, and there was no report on PMTCT programs before 2004, which may be because the Chinese ministry of health first issued guidelines on PMCTC in 2004[6].Our review showed that the overall uptake of PMTCT programs was low and did not reach the 80% target that was setby the United Nations General Assembly Special Session(UNGASS)[74]. The estimated percentage of antiretroviral therapy in HIV-positive pregnant women was still unsatisfactory. We estimated that the MTCT rate in China was 4.4% (95% CI, 3.2–5.5), which was substantially higher than in the U.S. and Europe (less than 1%), while it was lower than some low- and middle-income countries in Sub-Saharan Africa (11%)[1,75]. Great successes in reducing the MTCT rate has been achieved in China (reduced from 11.8% in 2005 to 4.2% in 2009) due to the scale up of PMTCT programs since the Ministry of Health launched PMTCT programs in 2003. In 2001 UNGASS set a goal that would reduce theproportion of HIV infected infants by 50% in ten years, and in order to achieve this target they estimated that 80% of pregnant women andtheir children need to receive PMTCT programs service [74]. Despite efforts to increase the uptake of PMTCT interventions services, coverage is still lower than desired in China. Many international non-governmental organizations, such as the UN Secretary General, G8 countries, the Global Fund toFight AIDS, WHO and so on have committed to further develop and improve the quality and effectiveness ofPMTCT service coverage in low- and middle-income countries[75]. Integration of PMTCT with other healthcare services, such as maternal, newborn, and child health may be a crucialcomponent of the strategy to scale up PMTCT programs. In China, PMTCT services were integrated with antenatal care and perinatal care, pregnant women were provided with HIV testing and counseling and HIV positivepregnantwomen were provided with antiretroviral prophylaxis in antenatal care and attending labor ward.Discouragingly, a recent review noted very limited, non-generalizableevidence of improved PMTCT intervention uptake in integratedPMTCT programscompared to non- or partially integrated services[76].A reviewassessing the role of family planning in eliminating new pediatric HIV infectionsreported that integrating family planning and HIV services is an effective strategy for increasing access to contraception among women with HIV who do not wish to become pregnant, which could accelerate the ending of new pediatric HIV infections[77]. In recent years, PMTCT servicewas also integrated with family planning service in China; HIV testing was provided forwomen of childbearing age when attending national free pre-pregnancy eugenic health check project, and the HIV-positive women were suggested that they should receive antiretroviral therapy before pregnancy or prevent unintended pregnancies by the use of contraception. But the coverage of integrated family planning/HIV service was very low in China, which prompt the Chinese government to call for increaseddomestic and international financing to expand the uptake of PMTCT.

We noted significant heterogeneity within studies in this meta-analysis, and meta-regression analyses revealed that year of publication was the main factors that explained much of the heterogeneity between studies.PMTCT programs have changed significantly over the years, and there are guidelines for starting ART for both women and infants. While this is acknowledged, treating all studies from 2000 to 2014 as equivalent leads to very heterogeneous data. For example, if the risk of MTCT was high in 2000, when presumably no ART was administered, it is unfair to combine these data with recent guidelines to provide ART if CD4<500 or lifelong ART (Option B+). Therefore, we performed subgroup analysis by years and present the historical and current policies for PMTCT services.Study region and income level may also account for much of the heterogeneity between studies. For example, northwest China had the highest MTCT rate (5.9%)and lowest uptake of PMTCT programs services; the high income region usually reported the highest percentages of voluntary HIV-counseling (93.2%) and voluntary HIV-testing (94.9%).The variation between regions and income levels were consistent with the global uptake of HIV testing; the low income countries are reported to have low uptake of HIV testing, and the coverage for early infant diagnosis of HIV was below 6% in some low income countries (Angola, Nigeria, Malawi, Democratic Republic of Congo, and Chad) in 2012[78,79].Such variation could be explained by lower government financial investment, limited health resources and inefficient programs implementation strategy in regions with low uptake of PMTCT services.Voluntary counseling and testing (VCT) was effective in reducing MTCT as well as cost effective as a PMTCT intervention. The WHO had recommend that all children younger than 2 years old who are living with HIV should be treated, and the important first step was to identify the HIV-infected children through developing effective strategies for HIV testing. Although HIV testing facilities have increased over the past ten years, the uptake of VCT has still been low; UNAIDS reported in 2012 that 50% of individuals living with HIV were unaware of their HIV status[80]. Encouraging data are presented in this review, including that the estimated percentage of voluntary HIV-testing in pregnant women continually increased from 57.9% in 2004 to 98.5% in 2012 and that the estimated infant free HIV antibody testing rate over 18 months of age increased from 81% in 2005 to 97.7% in 2012. The number of new HIV-infected children in the 21 priority African countries in the UN Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) global plan decreased by 38% between 2009 and 2012 because of increased access to antiretroviral treatment to prevent MTCT[81,82]. We estimated that more than 70% of HIV-infected pregnant women never received antiretroviral treatmentin antenatal care in China, which is significant lower than that in low- and middle- income countries with only 55% (range 22–99%) of HIV positive women starting highly active antiretroviral therapy in antenatal care[75,83]. An encouraging result in this meta-analysis was that initiating ARP in exposed infants continually increased from 77.0% in 2005 to 98.1% in 2012, which achieved the goal of the 12thFive-Year action plan on containment, prevention and control of HIV/AIDS that the percentage of HIV exposed infants who received ARV would be more than 90% by the year 2015[84]. According to recently WHO report, the use of combination ART during pregnancy is preferable to single therapy[85]. The combination ART is more effective at PMTCT, and it has the advantages of reducing sexual HIV transmission and HIV-associated morbidity and mortality[86]. In China, we estimated that approximately 31.3% (95% CI, 15.5–47.0) of women with HIV received the combination of three antiretroviral drugs (AZT+3TC/AZT+NVP), and < 1% of exposed infants received the combination of three antiretroviral drugs.

Despite the great successes in reducing MTCT in China, we are facing many challenges, such as low coverage of PMTCT programs, stigma and discrimination, drug resistance, and delayed infant HIV diagnosis[5]. This review had several limitations; firstly, significant heterogeneity between studies was observed. Although we performed subgroup analyses by publication year, geographical area, and income level, and these factors may be the sources of between-study heterogeneity. However other unmeasured characteristics in study population and limitations of the included studies likely influence the detected heterogeneity; unfortunately, we did not obtain enough information about these aspects for further analysis. Secondly, we have only conducted the search in electronic databases. Studies published in local journals which are not indexed in electronic databases might have been missed out in this review. The third, results from Begg’s funnel plot and Egger’s test are different but the funnel plot and Trim and Fill methods suggested the presence of a potential publication bias, a language bias, and inflated estimates by a flawed methodological design in smaller studies.The last, some pooled estimates in subgroups should be interpreted with caution due the small number studies.

In conclusion, PMTCT programs have scaled up quickly in recent years in China. However, antiretroviral therapy in HIV-positive pregnant, antiretroviral prevention and HIV diagnosis in exposed infants were still unsatisfactory. Moreover, there was a big gap of uptake of PMTCT programs between regions and income levels. These results highlight the need to further scale up PMTCT services, especially in regions with the lowest coverage, so that more women can access and utilize them.

Supporting Information

(DOC)

Search terms consisted of the following key wordsincludingPMTCT, HIV, and China were provided.

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all for their valuable contributions to this article.

Data Availability

Data are included within the paper and its Supporting Information.

Funding Statement

The authors have no support or funding to report.

References

- 1. Shetty AK (2013) Epidemiology of HIV infection in women and children: a global perspective. Current HIV research 11: 81–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO. PMTCT Strategic Vision 2010–2015: Preventing mother-to-child transmission of HIV to reach the UNGASS and Millenium Development Goals. 2010. Available: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/mtct/strategic_vision/en/. Accessed 28 July 2014.

- 3. UNICEF. Global update on HIV treatment 2013: results, impact and opportunities Geneva: UNICEF, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Maartens G, Celum C, Lewin SR (2014) HIV infection: epidemiology, pathogenesis, treatment, and prevention. Lancet 384: 258–271. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60164-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kalembo FW, Maggie Z, Du YK(2013) Progress of mother-to-child transmission of HIV programs in China: successes, challenges and way forward. Chinese medical journal 126: 3172–3176. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.China Ministry of Health, China Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Working guidelines to prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV. Available: http://www.chinaids.org.cn. Accessed 28 July 2014.

- 7.UNAIDS. 2012 China AIDS Response Progress Report. Available: http://www.unaids.org/en/dataanalysis/knowyourresponse/countryprogressreports/2012countries/ce_CN_Narrative_Report[1].pdf. Accessed 27 July 2014.

- 8.WHO. PMTCT Strategic Vision 2010–2015. 2010. Available: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/mtct/strategic_vision/en/. Accessed 27 July 2014.

- 9.Wang Q (2006) Survey on needs and use of prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission services in some countries, China. [master]: Chinese Center For Disease Control And Prevention.

- 10. Lin AW, Wong KH, Chan K, Chan WK (2014) Accelerating prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV: ten-year experience of universal antenatal HIV testing programme in a low HIV prevalence setting in Hong Kong. AIDS care 26: 169–175. 10.1080/09540121.2013.819402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zhang SP, Yin HP, Hu K (2012) Analysis on data of HIV/AIDS counnseling and testing among pregnant and delvery women in demonstration zones of Anhui province. Anhui J Prev Med 18: 190–191. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Li B, Zhao Q, Zhang X, et al. (2013) Effectiveness of a prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission program in Guangdong province from 2007 to 2010. BMC public health 13: 591 10.1186/1471-2458-13-591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Chen ZY, Zhu Q (2010) An analysis of HIV test results among pregnant women in Henan province in 2005–2007. Chin J AIDS STD 4: 401–402. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Gong SY, Fang LW, Wang LH, et al. (2007) Utilization of MTCT prevention services by HIV-infected pregnant women and related impact factors. Chin J AIDS STD 13: 314–316,320. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lu QC, Shi JC, Ding L, Zhao T, Wang WM (2008) Prevent mother-to-child transmission intervention program in Nanyang city during from 2003 to 2007. Chin J AIDS STD 14: 508–509. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sun DY, Wang Q, Yang WJ (2008) HIV/AIDS prevalence in pregnant and lying in women and prevention of MTCT in Henan province. Chin J AIDS STD 14: 351–353. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wang XY, Fang LW, Wang F, Wang Q, Qiao YP, Wang AL. Analysis of HIV, Syphilis and HBV tesing services among pregant women in some counties of China. Chin J AIDS STD. 2013; 12: 880–2. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Wang Q, Wang LH, L.W. F (2013) Delivery conditions and pregnancy outcomes among HIV-infected pregnant women in high AIDS incidence areas of China. Chin J Public Health 29: 1417–1419. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wang WM, Chen ZY (2008) Effect analysis of prevent mother-to-child transmission intervention program on HIV-infected pregnant women in Henan province. Chin J Public Health 24: 4. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ailika S, Cui D, Maimaitiming A, Guan LL, Wang L(2013) Analysis on anti HIV drug application among HIV positive mothers and their children in Xinjiang, 2010–1012. Chinese Journal of Health Education 8: 687–689. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Wang Q, Fang LW, Wang LH (2013) Influencing factor analysis on anti-retroviral drugs application among HIV infected pregant women and their children in 5 provinces with HIV high prevalence in China. Chinese Journal of Health Education 29: 211–213. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wang XY, Fang LW, Wang LH, Wang F, Qiao YP (2010) An investigation of use of antiviral drugs for HIV-infected mothers in 6 counties of 4 provinces in China. Chinese Journal of Woman and Child Health Research 21: 282–284,326. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zhang XH, Lu W, Wu QY, Jiang JY, Chen DQ, Qiu LQ (2014) Progress in Prevention of Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIV-1 in Zhejiang Province, China, 2007–2013. Current HIV research. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24. Tan YM, Chen C, Huang YH, Lei LZ (2013) Report on HIV/AIDS monitoring among people attending premarital examination in Guangxi province, 2009–2010. Guangxi Medical Journal 4: 491–492. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Yang M, Mou HJ, Zhao H, Wang WR (2011) Analysis of prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV/AIDS intervention measures on 175 pregnant women. Guizhou Medical Journal 35: 162–3. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ma JZ, yue YC(2010) Effect of prevent mother-to-child transmission intervention on 36 HIV-infected pregnant women. Henan J Prev Med 21: 87,100. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bai Y, Zhang JP, Shan GS (2012) HIV/AIDS prevalence of PRG and prevention control of MTCT in Liuzhou City. J Med Pest Control 28: 836–838. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Dai GH, Yang Q, Ma L, Li XD, Wang D (2010) Prevalence of HIV/AIDS and prevention of mother-infant transmission among pregnant and lying-in women in Hubei. Maternal and Child Health Care of China 25: 4370–4372. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Hong Y, Yang L, Gong CY, Liu SQ, Shen YB(2009) Utilization and promoting strategies of prevent mother-to-child transmission intervention service in Yuxi city. Maternal and Child Health Care of China 24: 4647–4649. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Li Y(2012) The intervention program of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Bijie city, 2009–2011. Maternal and Child Health Care of China 27: 5450–5453. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Wang AL, Qiao YP, Su HQ, Wang LH (2006) Analysis of strategy and intervention program of prevent mother-to-child transmission among HIV-infected pregnant women. Maternal and Child Health Care of China 21: 1765–1766. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Wang Q, Hou ZS, Yang YY, Cai R, Yang L(2009) An analysis of prevent mother-to-child transmission program of HIV in a border county of Yunnan province during 2005–2008. Maternal and Child Health Care of China 24: 5182–5283. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Wang Q, Mao XM, Yang HJ (2012) Follow-up management of infants born by HIV-infected pregnant women from 2003 to 2009 in Kaiyuan city, Yunnan province. Maternal and Child Health Care of China 27: 4842–4844. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wang ZZ, Yan CR, Shi XD, Feng TJ (2007) Effect analysis of prevent mother-to-child transmission intervention program in Shenzhen city. Maternal and Child Health Care of China 22: 4858–4859. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Xiong YH, Liu DH, Yang JL, Wang W (2010) Effect analysis of prevent mother-to-child transmission intervention program on HIV-infected pregnant women in Honghe stata, 2005–2007. Maternal and Child Health Care of China 25: 2097–2100. [Google Scholar]

- 36. yang M, Mou HJ, Zhao H (2014) Effect analysis of prevent mother-to-child transmission intervention program in Guizhou province during from 2006 to 2011. Maternal and Child Health Care of China 29: 10–2. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zhang XH, Bao LQ, Qiu LQ (2009) Current situation of prevent mother-to-child transmission program in Zhejiang province. Maternal and Child Health Care of China 24: 152–153. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Zhu XX, Wang XT(2005) Pilot work of prevent mother-to-child transmission program in Yunnan province. Maternal and Child Health Care of China 20: 1430–1431. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Huang S, Xiao TM, Zhou T(2013) Epidemiological characteristics analysis of maternal women with HIV infection in Zhongshan city. Modern Hospital 13: 145–147. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Cheng WM, Zi XM, Zhang L (2009) Evaluation of effectiveness on prevention of HIV mother-to-child transmission. Modern Hospital Medicine 36: 1252–1253,1257. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Li T(2012) Analysis of the effect of PMTCT intervention in Butuo County. Modern Preventive Medicine 39: 2720–2721. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wang Q, Peng J, Cai R, Dong SL, Yang L (2011) Evaluation and analysis of comprehensive interventions on prevention of maternal-neonatal transission of AIDS in a border county of yunnan province. Modern Preventive Medicine 38: 34–36,38. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cheng WM, Zhang L, Shi XM, Yang PJ, Zhang HY (2006) The status of HIV antibody detection and prevent mother-to-child transmission in Zhoukou city. Occupation and Health 22: 2104–6. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Wu M, Liu JJ, Wu YL, Fang CY (2011) Analysis of HIV test results among pregnant women in Hunan from 2004 to 2010. Practical Preventive Medicine 18: 1058–1059. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Song J, Feng T, Bulterys M (2013) An integrated city-driven perinatal HIV prevention program covering 1.8 million pregnant women in Shenzhen, China, 2000 to 2010. Sexually transmitted diseases. 40: 329–334. 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3182805186 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Du M, Liu FJ, Shen HB, Zhang YY (2006) Prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Dali city. Soft Science of Health 20: 323–5. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ma Q (2012) Effect analysis of prevent mother-to-child transmission intervention program in Baoshan city, Yunnan province. Soft Science of Health 26: 230–231. [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wang QF, Chen MH (2011) Analysis report on prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV/AIDS in Qujing city, 2011. Today Nurse 8: 173–174. [Google Scholar]

- 49. Chen Y, Huo YH (2013) The status of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in eight counties of Xinjiang Yili state. Xinjiang Medicine 43: 162–164. [Google Scholar]

- 50. Jiang W, He L, Mao LQ, Wei JL, Qiu BQ, Yan JL (2013) Epidemiological characteristics of AIDS among pregnant women in Nanning City of Guangxi, 2009–2011. Chinese Journal of New Clinical Medicine 12: 1154–1157. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wang YX, Feng CZ, Peng XS, Zhang O (2011) Effectiveness evaluation of prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV in Jiangning, 2007–2010. Chinese Journal of Coal Industry Medicine 14: 877–878. [Google Scholar]

- 52. Chen L, Chen SX, Liao ZX, Huang XL, Zhang J (2013) Application of transmission blocking of HIV/AIDS from mother to child in poverty- stricken ethnic minority areas in Guangxi. China Tropical Medicine 13: 1074–1076. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Weng YQ, Shan GS, Qin L, Feng WD, Bai Y (2010) Results of monitoring of HIV infection in pregnant and lying-in women in Liuzhou City in 2008. China Tropical Medicine 10: 957–958. [Google Scholar]

- 54. Wen Y, Lu K, Yao N, Ren XQ (2011) Observation on the result of 7 years of implementation of mother-to-child AIDS transmission blocking project. Chinese Journal of Practical Pediatrics 26: 933–936. [Google Scholar]

- 55. Cao YZ, Dai BM, Wei FB, Zhang YM, Chen AJ, Lin LZ (2011) Analysis of pregnancy outcomes of 47 HIV-positive pregnant women. Modern Medicine Journal of China 13: 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- 56. Zhang HY, Xiao N, Zhou XJ, Zhang GD, Lin XN (2011) Chongqing HIV infected pregnant women received PMTCT interventions status and countermeasures. Chinese Journal of Birth Health & Heredity 19: 78–79. [Google Scholar]

- 57. Zhou FR, Zhang P, Fan YY, Chen ZX (2010) Maternal transmission of HIV in Shandong, 2008–2009. Chin Prev Med 7: 692–694. [Google Scholar]

- 58. F.L. A, Ling L (2009) Analysis of prevent HIV mother-to-child transmission of pregnant women in Xihua county. Chin J Dis Control Prev 13: 422,426. [Google Scholar]

- 59. Feng L, Yao X, Wu WL (2013) The infection status of the results of antenatal examination of hepatitis B virus (HBV), syphilis and HIV in Chongqing Banan District. Chin J Dis Control Prev 17: 178–179. [Google Scholar]

- 60. Liang K, Gui XE, Zhang YZ, Silafu R, Liu GR, Tang GZ (2011) Status and associated factors of termination of pregnancy among HIV-infected pregant women. Chin J Perinat Med 14: 550–551. [Google Scholar]

- 61. Wang FK (2009) Analysis of prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV (PMTCT) work in Zhumadian city, 2001–2009. Chin J Prev Med 43: 988–990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Fang LW, Wang LH, Wang XY, Wang F, Wang AL (2010) Analysis on the intervention services status of prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV/AIDS in China, 2005–2009. Chin J Prev Med 44: 1003–1006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Luo XM, Du JL, Zhou CY, Xiao ZL, Kang ZM, Yang MY (2011) Analysis of health care of pregnant women in some area of minority nationality in western Hunan. Chinese and forengh women health 19: 312–313. [Google Scholar]

- 64. Sun LD, Zhao QF, Li DM, Zhou LK (2011) Initial success have achieved on prevent mother-to-child transmission of HIV program in Shizong county, 2006–2010. Chinese and forengh women health 19: 453–454. [Google Scholar]

- 65. Jia LQ (2010) Status of prevent HIV mother-to-child transmission in Menghai County, Xishuangbanna state. China foreign medical treatment 29: 71–72. [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ministry of Civil Affairs of the People's Republic of China. Administrative division of the People's Republic of China. Available: http://www.xzqh.org.cn/. Accessed 1 July 2014.

- 67.Research centers of Chinese livable city. GDP and per capital GDP of Chinese provinces. Available: http:www.elivecity.cn. Accessed 1 July 2014.

- 68. Rostom A, Dubé C, Cranney A, et al. Celiac Disease Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US) Available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK35156/. Accessed 24 April 2015 [Google Scholar]

- 69. DerSimonian R, Laird N (1986) Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Controlled clinical trials 7: 177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Higgins JP, Thompson SG (2002) Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Statistics in medicine 21: 1539–1558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Higgins JP, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG (2003) Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 327: 557–560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Mantel N, Haenszel W(1959) Statistical aspects of the analysis of data from retrospective studies of disease. Journal of the National Cancer Institute 22: 719–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C (1997) Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ (Clinical research ed) 315: 629–634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Session UNGAS. Declaration of Commitment on HIV/AIDS. New York. 2001.

- 75. Tudor Car L, Brusamento S, Elmoniry H (2013) The uptake of integrated perinatal prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission programs in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. PloS one 8: e56550 10.1371/journal.pone.0056550 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Tudor Car L, Van Velthoven MH, Brusamento S, Elmoniry H, Car J, Majeed A (2012) Integrating prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission programs to improve uptake: a systematic review. PLoS One 7: e35268 10.1371/journal.pone.0035268 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Wilcher R, Petruney T, Cates W(2013) The role of family planning in elimination of new pediatric HIV infection.CurrOpin HIV AIDS 8: 490–497. 10.1097/COH.0b013e3283632bd7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. UNAIDS. Report on the Global AIDS Epidemic Geneva, Switzerland; UNAIDS; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 79. WHO. Global update on HIV treatment 2013: results, impact and opportunities Geneva: World Health Organization, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 80. UNAIDS. Together we will end AIDS Geneva: UNAIDS, 2012. Available: http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/20122/20120718_togetherwewillendaids_en.pdf. Accessed 27 July 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 81.UNAIDS. Progress report on the global plan towards the elimination of new HIV infections among children by 2015 and keeping their mothers alive. 2013. Available: http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/unaidspublication/2013/20130625_progress_global_plan_en.pdf. Accessed 30 July 2014.

- 82.UNAIDS. Report on the global AIDS epidemic 2013. Available: http://www.unaids.org/en/media/unaids/contentassets/documents/epidemiology/2013/gr2013/UNAIDS_Global_Report_2013_en.pdf. Accessed 30 July 2014.

- 83. Ferguson L, Grant AD, Watson-Jones D, Kahawita T, Ong'ech JO, Ross DA(2012) Linking women who test HIV-positive in pregnancy-related services to long-term HIV care and treatment services: a systematic review. Tropical medicine & international health: TM & IH 17: 564–580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.The General Office of the State Council. The 12th Five-Year action plan on containment, prevention and control of HIV/AIDS in China. Available: http://www.gov.cn/zwgk/2012-02/29/content_2079097.htm. Accessed 30 Jan 2014.

- 85.WHO. Programatic update, Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating Pregnant Women and Preventing HIV Infection in Infants, Executive summary. 2012. Available: http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/mtct/programmatic_update2012/en/. Accessed 1 July 2014.

- 86. Kesho Bora Study G, de Vincenzi I (2011) Triple antiretroviral compared with zidovudine and single-dose nevirapine prophylaxis during pregnancy and breastfeeding for prevention of mother-to-child transmission of HIV-1 (Kesho Bora study): a randomised controlled trial. The Lancet infectious diseases 11: 171–180. 10.1016/S1473-3099(10)70288-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOC)

Search terms consisted of the following key wordsincludingPMTCT, HIV, and China were provided.

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

Data are included within the paper and its Supporting Information.