Abstract

Background

Iron deficiency anaemia is common in patients with chronic kidney disease, and intravenous iron is the preferred treatment for those on haemodialysis. The aim of this trial was to compare the efficacy and safety of iron isomaltoside 1000 (Monofer®) with iron sucrose (Venofer®) in haemodialysis patients.

Methods

This was an open-label, randomized, multicentre, non-inferiority trial conducted in 351 haemodialysis subjects randomized 2 : 1 to either iron isomaltoside 1000 (Group A) or iron sucrose (Group B). Subjects in Group A were equally divided into A1 (500 mg single bolus injection) and A2 (500 mg split dose). Group B were also treated with 500 mg split dose. The primary end point was the proportion of subjects with haemoglobin (Hb) in the target range 9.5–12.5 g/dL at 6 weeks. Secondary outcome measures included haematology parameters and safety parameters.

Results

A total of 351 subjects were enrolled. Both treatments showed similar efficacy with >82% of subjects with Hb in the target range (non-inferiority, P = 0.01). Similar results were found when comparing subgroups A1 and A2 with Group B. No statistical significant change in Hb concentration was found between any of the groups. There was a significant increase in ferritin from baseline to Weeks 1, 2 and 4 in Group A compared with Group B (Weeks 1 and 2: P < 0.001; Week 4: P = 0.002). There was a significant higher increase in reticulocyte count in Group A compared with Group B at Week 1 (P < 0.001). The frequency, type and severity of adverse events were similar.

Conclusions

Iron isomaltoside 1000 and iron sucrose have comparative efficacy in maintaining Hb concentrations in haemodialysis subjects and both preparations were well tolerated with a similar short-term safety profile.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease, iron isomaltoside 1000, iron treatment

INTRODUCTION

Patients on haemodialysis frequently suffer from anaemia due to relative reduced renal erythropoietin production, as well as absolute and functional iron deficiency [1–3]. The latter can be optimally managed by intravenous (IV) iron repletion, which is superior to oral iron in this patient population [4–8].

It is estimated that a patient on haemodialysis loses 2–3 g of iron per year [9]. The Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines recommend a trial of IV iron administration to patients on haemodialysis, [4] since maintenance of stable haemoglobin (Hb) and iron stores remains challenging due to continuous blood loss and increased iron utilization in this patient population. The KDIGO guidelines recommend that when prescribing iron therapy, one must first balance the potential benefits of avoiding or minimizing blood transfusions, erythropoiesis stimulating agent (ESA) therapy and anaemia-related symptoms against the risks of harm in individual patients of use of IV iron. In adult chronic kidney disease (CKD) patients with anaemia and who are not on iron or ESA therapy, the guideline suggests a trial of IV iron if an increase in Hb concentration without starting ESA treatment is desired and the transferrin saturation (TSAT) is <30% and ferritin is <500 ng/mL. For adult CKD patients on ESA therapy who are not receiving iron supplementation, the guideline suggests a trial of IV iron if an increase in Hb concentration or a decrease in ESA dose is desired and the TSAT is <30% and ferritin is <500 ng/mL. Subsequent iron administration in CKD patients is based on Hb responses to recent iron therapy, as well as ongoing blood losses, iron status tests (TSAT and ferritin), Hb concentration, ESA responsiveness and ESA dose in ESA-treated patients, trends in each parameter and the patient's clinical status.

Iron sucrose (Venofer®) is currently one of the most widely used IV iron in haemodialysis patients with long-established efficacy and short-term safety [10, 11]. Compared with more recently introduced IV iron products, the iron is more loosely bound in iron sucrose [12]. This is associated with catalytic/labile iron which has been hypothesized to cause increased oxidative stress with potential consequences on long-term toxicity [13, 14]. The potential clinical risk in relation to e.g. increased risk of infection and cardiovascular morbidity is not known.

Iron complexes with more tightly bound iron such as iron isomaltoside 1000 (Monofer®) may offer a lower risk of labile iron toxicity from its binding to the carbohydrate moiety and hence a possibility of larger dose per administration [12]. The fact that a larger dose may be administered may be an advantage since according to the European Medicine Agency (EMA) there is a risk of an allergic reaction with every dose of IV iron that is given [15]. Currently, the larger single dose possibility has not been directly compared with more frequent lower dosing.

The aim of this head-to-head comparative trial was to explore the efficacy and short-term safety of iron isomaltoside 1000 administered as a single bolus or split bolus injection compared with iron sucrose in haemodialysis patients. The primary objective was to demonstrate that iron isomaltoside 1000 is non-inferior to iron sucrose in maintaining Hb levels between 9.5 and 12.5 g/dL. The secondary objectives were to assess other relevant haematology parameters, the effect on quality of life (QoL) and safety.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Trial design

This prospective, randomized, comparative, open-label, non-inferiority, multi-centre trial was conducted from June 2011 to October 2013. The protocol and amendments were approved by local ethics committees/Institutional Review Boards and competent authorities (EudraCT number: 2010-023471-26). The trial was conducted in accordance with good clinical practice and the Declaration of Helsinki. The trial was registered at ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT01222884) 15 October 2010. Informed consent was obtained in writing prior to any trial-related activities.

Participants

The trial took place at 48 sites (hospitals or private dialysis clinics); 16 centres in India, 14 centres in the UK, 4 in Russia, 4 in Poland, 3 in Sweden, 3 in Switzerland, 2 in Romania, 1 in Denmark and 1 in the USA. Subjects ≥18 years of age with a diagnosis of CKD and on haemodialysis therapy for at least 90 days, Hb concentration between 9.5 and 12.5 g/dL (inclusive both values) both at screening visit 1a and screening visit 1b (screening visits were separated by at least 1 week), serum-ferritin <800 ng/mL, TSAT < 35% and receiving ESA treatment with stable dose for the previous 4 weeks prior to screening were enrolled. The complete inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria:

|

Interventions

All subjects received a cumulative dose of 500 mg iron.

Subjects in subgroup A1 were administered iron isomaltoside 1000 as a single undiluted IV bolus injection of 500 mg over ∼2 min at baseline, subjects in subgroup A2 were administered undiluted iron isomaltoside 1000 in split doses of 100 mg at baseline and 200 mg each at Weeks 2 and 4 as IV bolus injections over ∼2 min. Subjects in Group B were administered undiluted iron sucrose in split doses of 100 mg at baseline and 200 mg each at Weeks 2 and 4. The doses of iron sucrose were administered as per local summary product of characteristics or package insert and/or local hospital guidelines, as applicable.

All dosages were administered during dialysis, at least 30 min after the start and at least 1 h before the end of dialysis.

During the trial, the subjects were prohibited from having a blood transfusion and any iron supplementation other than investigational product starting from visit 1a.

Treatment with ESA had to be kept stable during the trial. The patients received different dosing schedules with various ESAs including epoetin alfa, epoetin beta, darbepoetin alfa, erythropoietin and methoxy polyethylene glycol-epoetin beta.

Objective and outcomes

The subjects attended six visits: screening visit (visit 1 was divided into visit 1a and visit 1b; visit 1a was held within 16 days before the baseline visit), baseline (visit 2), three on-treatment and follow-up visits (visits 3–5) and one end-of-trial visit (visit 6) during an 8-week period.

The trial was designed with the primary objective to demonstrate non-inferiority.

The primary efficacy outcome was to determine the proportion of subjects who were able to maintain Hb between 9.5 and 12.5 g/dL (inclusive both values) at Week 6. The secondary efficacy outcome included assessment of the change in Hb concentration from baseline to Weeks 2, 4 and 6, change in concentrations of serum-iron, TSAT, serum-ferritin and reticulocyte count from baseline to Weeks 1, 2, 4 and 6, and change in total QoL score (Linear Analogue Scale Assessment) from baseline to Weeks 4 and 6. The safety outcomes of the trial were to determine the number of subjects who experienced any adverse drug reaction (ADR), including any suspected unexpected serious adverse reaction and safety laboratory assessments. The primary outcome was tested for non-inferiority whereas the remaining outcomes were tested for superiority.

Sample size and randomization

A stratified block randomization methodology was used in the trial to assign subjects in a 1 : 1 : 1 ratio (2 : 1 randomization to Groups A and B) to receive either iron isomaltoside 1000 as a single dose (Group A1), iron isomaltoside 1000 as a split dose (Group A2) or iron sucrose (Group B). The block size was six. The randomization list was prepared by a Contract Research Organization, Max Neeman International Data Management Centre, using a validated computer program (SAS 9.1.3, SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) PROC PLAN procedure. An interactive web response system (IWRS) was used to randomize the subjects to the treatment groups. When the patient data had been entered into the IWRS, a unique randomization number was generated, which identified the treatment the patient was allocated to. The randomization of patient was stratified by serum-ferritin (<100 versus ≥100 ng/mL).

The trial was not blinded, however, since the primary outcome was a biochemical measurement it is unlikely to be affected by the open-label trial design.

With a 2 : 1 randomization, a two-sided significance level of 0.05, and a non-inferiority margin of 10% point, there was 80% power to demonstrate non-inferiority with 214 subjects in Group A and 107 subjects in Group B. Less than 10% of drop-outs were expected. As the trial was designed to demonstrate non-inferiority, the analyses of the full analysis set (FAS) and the per protocol (PP) population should lead to similar conclusions and therefore the analyses for both analyses sets needed to be powered properly. With ∼10% (anticipated) of subjects having major protocol violations, a total of 351 subjects were to be randomized (234 to iron isomaltoside 1000 and 117 to iron sucrose).

Statistical methods

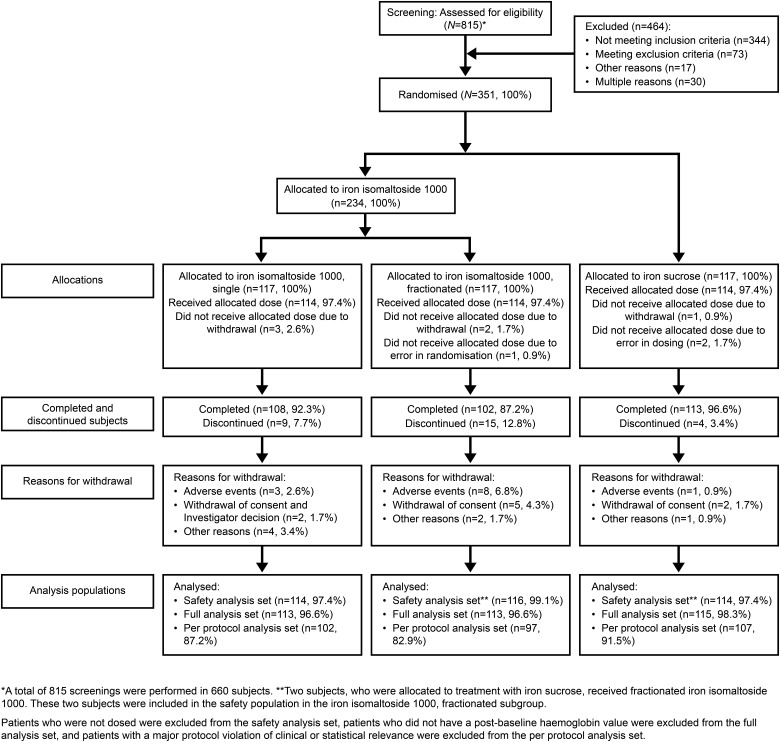

The following data sets were used in the analyses (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1:

Patient disposition.

The randomized population (N = 351) included all subjects who were randomized in the trial. The safety population (N = 344) included all subjects who were randomized and received at least one dose of the trial drug. The FAS population (N = 341) included all subjects who were randomized into the trial, received at least one dose of the trial drug, and had at least one post-baseline Hb assessment. The PP population (N = 306) included all subjects in the FAS who did not have any major protocol deviation of clinical or statistical relevance.

The primary efficacy analyses were conducted on FAS and PP populations, secondary efficacy analyses on the FAS population and the safety analysis was conducted on the safety population.

The primary outcome was summarized using number and percentage of subjects. A generalized linear model using the identity link function was used to compare the proportion of subjects with Hb concentration between 9.5 and 12.5 g/dL (both values included) at Week 6 using the last observation carried forward approach. Treatment and stratum (serum-ferritin (<100 versus ≥100 ng/mL) were used as factors and baseline value as a covariate. The mixed model for repeated measures (MMRM) was used to compare the average change in Hb concentration from baseline to Weeks 2, 4 and 6, change in serum-iron, TSAT, serum-ferritin and reticulocyte count from baseline to Weeks 1, 2, 4 and 6, and the change in QoL score from baseline to Weeks 4 and 6 with the use of treatment, visit, treatment*visit interactions, country, and stratum as factors and baseline values as covariates. The Proc MIXED procedure of SAS was used for the MMRM analysis with the model factor (visit*treatment estimate at the relevant week) and least-square means and estimate statements for treatment estimates and contrasts between the treatments, respectively.

The baseline characteristics and safety data were displayed descriptively. All tests were two-tailed and the significance level was 0.05.

RESULTS

Subjects

A total of 660 subjects were screened in the period 14 June 2011 to 10 September 2013, of whom 351 subjects were randomized 2 : 1 into Group A (234 subjects) and Group B (117 subjects). Group A was further subdivided into subgroups A1 (single dose, 117 subjects) and A2 (split dose, 117 subjects). The last patient visit was 28 October 2013.

Of the 351 subjects enrolled, 323 (92%) subjects completed the trial and 28 (8%) subjects discontinued. The details of patient disposition are summarized in Figure 1.

Patient demographics and baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 2 and baseline laboratory parameters are summarized in Table 3. Overall baseline characteristics in Groups A and B were comparable except for a higher proportion of ischaemic heart disease at inclusion in Group A (32/234; 13.7%) compared with Group B (8/117; 6.8%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Summary of baseline demographics and screening laboratory values for iron isomaltoside 1000 and iron sucrose, randomized population

| Statistics/category | Treatment group |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Iron isomaltoside 1000 (n = 234) | Iron sucrose (n = 117) | Overall (N = 351) | |

| Age (years) | |||

| n | 233 | 117 | 350 |

| Mean | 60.13 | 59.50 | 59.92 |

| SD | 16.21 | 15.39 | 15.92 |

| Median | 63.00 | 62.00 | 62.00 |

| Range (min : max) | (18 : 89) | (26 : 84) | (18 : 89) |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Men | 157 (67.1) | 74 (63.2) | 231 (65.8) |

| Women | 76 (32.5) | 43 (36.8) | 119 (33.9) |

| Ethnic origin, n (%) | |||

| Caucasian | 154 (65.8) | 74 (63.2) | 228 (65.0) |

| Black | 14 (6.0) | 5 (4.3) | 19 (5.4) |

| Asian | 64 (27.4) | 37 (31.6) | 101 (28.8) |

| Others | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.9) | 2 (0.6) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||

| n | 232 | 117 | 349 |

| Mean | 27.65 | 27.41 | 27.57 |

| SD | 6.77 | 6.34 | 6.62 |

| Median | 25.85 | 26.37 | 25.90 |

| Range (min : max) | (15.3 : 55.8) | (17.1 : 44.3) | (15.3 : 55.8) |

| Mean dialysis time before entering the trial (years) | |||

| n | 233 | 117 | 350 |

| Mean | 3.46 | 3.59 | 3.50 |

| SD | 3.95 | 4.08 | 3.98 |

| Median | 2.19 | 2.37 | 2.23 |

| Range (min : max) | (0.25 : 26.82) | (0.27 : 22.25) | (0.25 : 26.82) |

| Common concomitant illness, n (%) | |||

| Diabetes mellitus | 83 (35.5) | 36 (30.8) | 119 (33.9) |

| Hypertension arterial | 160 (68.4) | 87 (74.4) | 247 (70.4) |

| Ischaemic heart disease | 32 (13.7) | 8 (6.8) | 40 (11.4) |

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) at screening | |||

| n | 234 | 117 | 351 |

| Mean (SD) | 11.2 (0.66) | 11.0 (0.76) | 11.1 (0.69) |

| Median (min : max) | 11.2 (9.5 : 12.5) | 11.0 (9.5 : 12.5) | 11.1 (9.5 : 12.5) |

| Transferrin saturation (%) | |||

| n | 234 | 117 | 351 |

| Mean (SD) | 21.6 (5.95) | 22.6 (6.76) | 21.9 (6.24) |

| Median (min : max) | 21 (7.0 : 34.4) | 23 (8.0 : 34.8) | 22 (7.0 : 34.8) |

| Serum-ferritin (ng/mL) at screening | |||

| n | 234 | 117 | 351 |

| Mean (SD) | 367 (180) | 384 (184) | 373 (181) |

| Median (min : max) | 362 (7.2 : 791) | 376 (7.8 : 798) | 367 (7.2 : 798) |

| C-reactive protein (ng/mL) at screening | |||

| n | 234 | 117 | 351 |

| Mean (SD) | 6.85 (7.33) | 7.61 (10.1) | 7.1 (8.37) |

| Median (min : max) | 5 (0.37 : 49) | 5 (0.42 : 78) | 5 (0.37 : 78) |

Table 3.

Baseline laboratory parameters, FAS

| Parameter | Iron isomaltoside 1000 (n = 226) | Iron sucrose (n = 115) |

|---|---|---|

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | ||

| n | 225 | 114 |

| Mean (SD) | 11.20 (0.83) | 11.08 (0.93) |

| Median (min : max) | 11.21 (9.1 : 15.6) | 11.00 (8.4 : 14.6) |

| Serum-iron (µg/dL)a | ||

| n | 225 | 113 |

| Mean (SD) | 57.87 (22.48) | 60.22 (22.43) |

| Median (min : max) | 54.19 (5.03 : 172.07) | 59.00 (14.00 : 122.00) |

| Transferrin saturation (%) | ||

| n | 225 | 113 |

| Mean (SD) | 22.20 (17.90) | 22.57 (8.49) |

| Median (min : max) | 20.00 (2.0 : 265.0) | 22.00 (5.5 : 48.2) |

| Serum-ferritin (ng/mL) | ||

| n | 225 | 114 |

| Mean (SD) | 350.88 (186.17) | 357.74 (192.98) |

| Median (min : max) | 338.00 (9.5 : 997.6) | 333.50 (12.4 : 986.7) |

| Reticulocyte count (%) | ||

| n | 216 | 110 |

| Mean (SD) | 1.33 (0.6) | 1.26 (0.55) |

| Median (min : max) | 1.30 (0.1 : 3.1) | 1.25 (0.1 : 2.6) |

aConversion factor for serum-iron: µg/dL × 0.179 = µmol/L.

Exposure to iron

All subjects, who were dosed, received a cumulative dose of 500 mg iron.

Efficacy results

Proportion of subjects who were able to maintain Hb between 9.5 and 12.5 g/dL

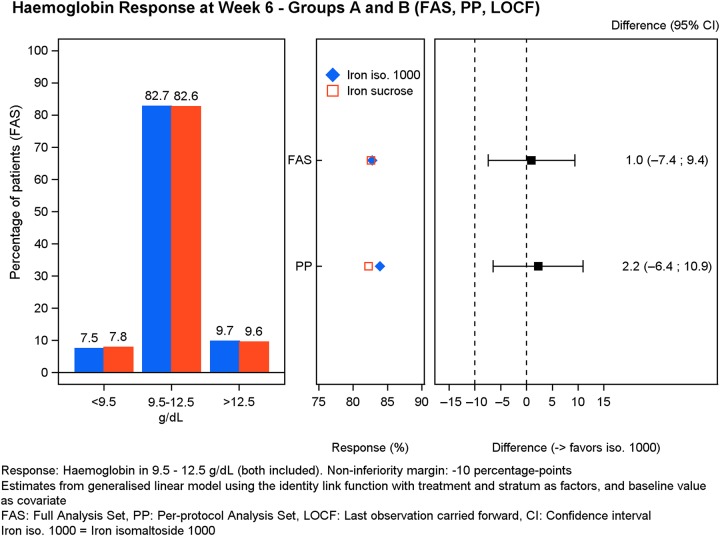

The primary analysis was conducted on the FAS (N = 341) and PP analysis set (N = 306).

The primary analysis in both FAS and PP populations showed that the majority (>82%) of subjects treated with either iron isomaltoside 1000 (FAS: 187/226; PP: 167/199) or iron sucrose (FAS: 95/115; PP: 88/107) were able to maintain Hb between 9.5 and 12.5 g/dL at Week 6 (Figure 2). The test for non-inferiority showed that iron isomaltoside 1000 was non-inferior to iron sucrose (FAS: P = 0.01; PP: P = 0.006) (Figure 2). Non-inferiority was also shown when comparing subgroup A2 (FAS: 95/113; PP: 83/97) to B (FAS: P = 0.01; PP: P = 0.006), whereas subgroup A1 only showed non-inferiority in the PP population (84/102) but not in the FAS population (92/113) when compared with B (FAS: P = 0.06; PP: P = 0.04).

FIGURE 2:

Hb response at Week 6.

Change in laboratory parameters

The change in laboratory parameters (secondary outcomes) was conducted on the FAS (N = 341).

The estimated effect size for the laboratory parameters including its precision are shown for Group A compared with B in Table 4, Group A1 compared with B in Table 5, Group A2 compared with B in Table 6 and Group A1 compared with A2 in Table 7.

Table 4.

Laboratory parameters: estimated effect size and its precision, Group A versus B, FAS

| Laboratory parameter, time point (number of subjects) | Iron isomaltoside 1000 (Group A), least-square mean estimatea | Iron sucrose (Group B), least-square mean estimatea | Difference estimates (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | ||||

| Week 2 (Group A: 219, Group B: 115) | 0.107 | −0.00664 | 0.114 (−0.0314;0.259) | 0.1 |

| Week 4 (Group A: 213, Group B: 114) | 0.0631 | 0.00852 | 0.0546 (−0.113;0.223) | 0.5 |

| Week 6 (Group A: 216, Group B: 113) | −0.00694 | −0.0277 | 0.0208 (−0.204;0.246) | 0.9 |

| Serum-iron (µg/dL) | ||||

| Week 1 (Group A: 221, Group B: 112) | 7.27 | 4.04 | 3.24 (−1.1;7.57) | 0.1 |

| Week 2 (Group A: 220, Group B: 115) | 5.39 | 3.29 | 2.1 (−4.45;8.65) | 0.5 |

| Week 4 (Group A: 212, Group B: 114) | 3.72 | 5.72 | −2 (−7.06;3.07) | 0.4 |

| Week 6 (Group A: 216, Group B: 113) | 4.08 | 4.04 | 0.0368 (−5.39;5.46) | 0.9 |

| Transferrin saturation (%) | ||||

| Week 1 (Group A: 221, Group B: 111) | 0.453 | 6.98 | −6.52 (−21.4;8.33) | 0.4 |

| Week 2 (Group A: 220, Group B: 115) | 0.137 | −1.06 | 1.2 (−1.35;3.75) | 0.4 |

| Week 4 (Group A: 212, Group B: 114) | −0.631 | 0.366 | −0.997 (−3.09;1.1) | 0.3 |

| Week 6 (Group A: 216, Group B: 113) | −0.0497 | −0.029 | −0.0207 (−2.12;2.08) | 0.9 |

| Serum-ferritin (ng/mL) | ||||

| Week 1 (Group A: 221, Group B: 113) | 147 | 39.1 | 108 (88;128) | <0.001 |

| Week 2 (Group A: 220, Group B: 115) | 135 | 11.3 | 123 (96.4;150) | <0.001 |

| Week 4 (Group A: 212, Group B: 114) | 126 | 76.4 | 49.3 (18.2;80.5) | 0.002 |

| Week 6 (Group A: 216, Group B: 114) | 130 | 145 | −15.1 (−54.2;24.1) | 0.4 |

| Reticulocyte count (%) | ||||

| Week 1 (Group A: 212, Group B: 108) | 0.165 | 0.0106 | 0.154 (0.0664;0.242) | <0.001 |

| Week 2 (Group A: 211, Group B: 111) | 0.0933 | 0.0494 | 0.0439 (−0.0475;0.135) | 0.3 |

| Week 4 (Group A: 204, Group B: 110) | 0.0949 | 0.0647 | 0.0302 (−0.0614;0.122) | 0.5 |

| Week 6 (Group A: 207, Group B: 109) | 0.105 | 0.0327 | 0.0727 (−0.028;0.173) | 0.2 |

Conversion factor for serum-iron: µg/dL × 0.179 = µmol/L.

aLeast-square means from repeated measures model with treatment, visit, stratum (serum-ferritin <100 versus ≥100 ng/mL) and country as factors, baseline value as a covariate and the interaction between treatment and visit.

Table 5.

Laboratory parameters: estimated effect size and its precision, Group A1 versus B, FAS

| Laboratory parameter, time point (number of subjects) | Iron isomaltoside 1000 (Group A1), least-square mean estimatea | Iron sucrose (Group B), least-square mean estimatea | Difference estimates (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | ||||

| Week 2 (Group A1: 110, Group B: 115) | 0.155 | −0.00664 | 0.162 (0.00389;0.32) | 0.05 |

| Week 4 (Group A1: 109, Group B: 114) | 0.0958 | 0.00852 | 0.0872 (−0.109;0.284) | 0.4 |

| Week 6 (Group A1: 110, Group B: 113) | −0.0256 | −0.0277 | 0.00213 (−0.245;0.25) | 0.9 |

| Serum-iron (µg/dL) | ||||

| Week 1 (Group A1: 112, Group B: 112) | 15.1 | 4.04 | 11.1 (5.72;16.5) | <0.001 |

| Week 2 (Group A1: 111, Group B: 115) | 6.64 | 3.29 | 3.35 (−3.66;10.4) | 0.3 |

| Week 4 (Group A1: 109, Group B: 114) | 5.6 | 5.72 | −0.114 (−5.65;5.43) | 0.9 |

| Week 6 (Group A1: 110, Group B: 113) | 2.64 | 4.04 | −1.4 (−7.41;4.6) | 0.6 |

| Transferrin saturation (%) | ||||

| Week 1 (Group A1: 112, Group B: 111) | 3.79 | 6.98 | −3.19 (−18.1;11.7) | 0.7 |

| Week 2 (Group A1: 111, Group B: 115) | 1.53 | −1.06 | 2.59 (−0.997;6.19) | 0.2 |

| Week 4 (Group A1: 109, Group B: 114) | 0.211 | 0.366 | −0.155 (−2.53;2.21) | 0.9 |

| Week 6 (Group A1: 110, Group B: 113) | −0.896 | −0.029 | −0.867 (−3.3;1.57) | 0.5 |

| Serum-ferritin (ng/mL) | ||||

| Week 1 (Group A1: 112, Group B: 113) | 252 | 39.1 | 213 (184;242) | <0.001 |

| Week 2 (Group A1: 111, Group B: 115) | 236 | 11.3 | 225 (185;265) | <0.001 |

| Week 4 (Group A1: 109, Group B: 114) | 155 | 76.4 | 78.6 (38;119) | <0.001 |

| Week 6 (Group A1: 110, Group B: 114) | 103 | 145 | −41.8 (−83.6;0.0552) | 0.05 |

| Reticulocyte count (%) | ||||

| Week 1 (Group A1: 107, Group B: 108) | 0.209 | 0.0106 | 0.199 (0.0863;0.311) | <0.001 |

| Week 2 (Group A1: 106, Group B: 111) | 0.105 | 0.0494 | 0.0559 (−0.0546;0.166) | 0.3 |

| Week 4 (Group A1: 105, Group B: 110) | 0.087 | 0.0647 | 0.0223 (−0.0959;0.14) | 0.7 |

| Week 6 (Group A1: 106, Group B: 109) | 0.101 | 0.0327 | 0.0687 (−0.0575;0.195) | 0.3 |

Conversion factor for serum-iron: µg/dL × 0.179 = µmol/L.

aLeast-square means from repeated measures model with treatment, visit, stratum (serum-ferritin <100 versus ≥100 ng/mL) and country as factors, baseline value as a covariate and the interaction between treatment and visit.

Table 6.

Laboratory parameters: estimated effect size and its precision, Group A2 versus B, FAS

| Laboratory parameter, time point (number of subjects) | Iron isomaltoside 1000 (Group A2), least-square mean estimatea | Iron sucrose (Group B), least-square mean estimatea | Difference estimates (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | ||||

| Week 2 (Group A2: 109, Group B: 115) | 0.0589 | −0.00664 | 0.0655 (−0.115;0.246) | 0.5 |

| Week 4 (Group A2: 104, Group B: 114) | 0.0304 | 0.00852 | 0.0219 (−0.193;0.237) | 0.8 |

| Week 6 (Group A2: 106, Group B: 113) | 0.0117 | −0.0277 | 0.0395 (−0.246;0.325) | 0.8 |

| Serum-iron (µg/dL) | ||||

| Week 1 (Group A2: 109, Group B: 112) | −0.591 | 4.04 | −4.63 (−9.65;0.397) | 0.07 |

| Week 2 (Group A2: 109, Group B: 115) | 4.14 | 3.29 | 0.85 (−6.42;8.12) | 0.8 |

| Week 4 (Group A2: 103, Group B: 114) | 1.84 | 5.72 | −3.88 (−10.1;2.32) | 0.2 |

| Week 6 (Group A2: 106, Group B: 113) | 5.51 | 4.04 | 1.48 (−5.55;8.5) | 0.7 |

| Transferrin saturation (%) | ||||

| Week 1 (Group A2: 109, Group B: 111) | −2.89 | 6.98 | −9.86 (−24.7;5.01) | 0.2 |

| Week 2 (Group A2: 109, Group B: 115) | −1.26 | −1.06 | −0.197 (−2.64;2.25) | 0.9 |

| Week 4 (Group A2: 103, Group B: 114) | −1.47 | 0.366 | −1.84 (−4.31;0.634) | 0.1 |

| Week 6 (Group A2: 106, Group B: 113) | 0.797 | −0.029 | 0.826 (−1.82;3.48) | 0.5 |

| Serum-ferritin (ng/mL) | ||||

| Week 1 (Group A2: 109, Group B: 113) | 41.8 | 39.1 | 2.62 (−16.3;21.6) | 0.8 |

| Week 2 (Group A2: 109, Group B: 115) | 33.3 | 11.3 | 21.9 (−4.33;48.2) | 0.1 |

| Week 4 (Group A2: 103, Group B: 114) | 96.5 | 76.4 | 20.1 (−14.3;54.4) | 0.3 |

| Week 6 (Group A2: 106, Group B: 114) | 157 | 145 | 11.7 (−34.5;57.8) | 0.6 |

| Reticulocyte count (%) | ||||

| Week 1 (Group A2: 105, Group B: 108) | 0.12 | 0.0106 | 0.109 (0.0154;0.203) | 0.02 |

| Week 2 (Group A2: 105, Group B: 111) | 0.0813 | 0.0494 | 0.0319 (−0.0728;0.137) | 0.5 |

| Week 4 (Group A2: 99, Group B: 110) | 0.103 | 0.0647 | 0.0381 (−0.0659;0.142) | 0.5 |

| Week 6 (Group A2: 101, Group B: 109) | 0.109 | 0.0327 | 0.0768 (−0.0417;0.195) | 0.2 |

Conversion factor for serum-iron: µg/dL × 0.179 = µmol/L.

aLeast-square means from repeated measures model with treatment, visit, stratum (serum-ferritin <100 versus ≥100 ng/mL) and country as factors, baseline value as a covariate and the interaction between treatment and visit.

Table 7.

Laboratory parameters: estimated effect size and its precision, Group A1 versus A2, FAS

| Laboratory parameter, time point (number of subjects) | Iron isomaltoside 1000 (Group A1), least-square mean estimatea | Iron isomaltoside 1000 (Group A2), least-square mean estimatea | Difference estimates (95% CI) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Haemoglobin (g/dL) | ||||

| Week 2 (Group A1: 110, Group A2: 109) | 0.155 | 0.0589 | 0.0966 (−0.0797;0.273) | 0.3 |

| Week 4 (Group A1: 109, Group A2: 104) | 0.0958 | 0.0304 | 0.0654 (−0.171;0.302) | 0.6 |

| Week 6 (Group A1: 110, Group A2: 106) | −0.0256 | 0.0117 | −0.0373 (−0.325;0.25) | 0.8 |

| Serum-iron (µg/dL) | ||||

| Week 1 (Group A1: 112, Group A2: 109) | 15.1 | −0.591 | 15.7 (10;21.5) | <0.001 |

| Week 2 (Group A1: 111, Group A2: 109) | 6.64 | 4.14 | 2.5 (−3.2;8.21) | 0.4 |

| Week 4 (Group A1: 109, Group A2: 103) | 5.6 | 1.84 | 3.77 (−2.2;9.73) | 0.2 |

| Week 6 (Group A1: 110, Group A2: 106) | 2.64 | 5.51 | −2.88 (−10.1;4.39) | 0.4 |

| Transferrin saturation (%) | ||||

| Week 1 (Group A1: 112, Group A2: 109) | 3.79 | −2.89 | 6.68 (4.24;9.11) | <0.001 |

| Week 2 (Group A1: 111, Group A2: 109) | 1.53 | −1.26 | 2.79 (−0.633;6.22) | 0.1 |

| Week 4 (Group A1: 109, Group A2: 103) | 0.211 | −1.47 | 1.68 (−0.751;4.12) | 0.2 |

| Week 6 (Group A1: 110, Group A2: 106) | −0.896 | 0.797 | −1.69 (−4.56;1.18) | 0.2 |

| Serum-ferritin (ng/mL) | ||||

| Week 1 (Group A1: 112, Group A2: 109) | 252 | 41.8 | 210 (183;238) | <0.001 |

| Week 2 (Group A1: 111, Group A2: 109) | 236 | 33.3 | 203 (162;244) | <0.001 |

| Week 4 (Group A1: 109, Group A2: 103) | 155 | 96.5 | 58.5 (16.6;100) | 0.006 |

| Week 6 (Group A1: 110, Group A2: 106) | 103 | 157 | −53.4 (−93.9;−13) | 0.01 |

| Reticulocyte count (%) | ||||

| Week 1 (Group A1: 107, Group A2: 105) | 0.209 | 0.12 | 0.0891 (−0.021;0.199) | 0.1 |

| Week 2 (Group A1: 106, Group A2: 105) | 0.105 | 0.0813 | 0.024 (−0.0894;0.138) | 0.7 |

| Week 4 (Group A1: 105, Group A2: 99) | 0.087 | 0.103 | −0.0158 (−0.142;0.11) | 0.8 |

| Week 6 (Group A1: 106, Group A2: 101) | 0.101 | 0.109 | −0.00807 (−0.146;0.13) | 0.9 |

Conversion factor for serum-iron: µg/dL × 0.179 = µmol/L.

aLeast-square means from repeated measures model with treatment, visit, stratum (serum-ferritin <100 versus ≥100 ng/mL) and country as factors, baseline value as a covariate and the interaction between treatment and visit.

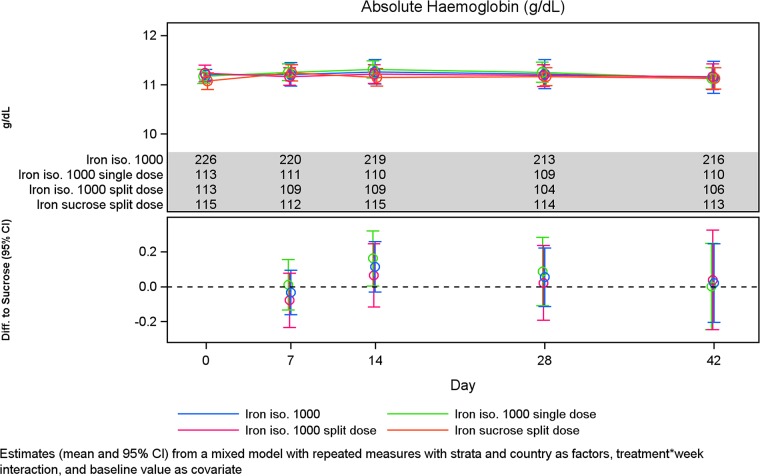

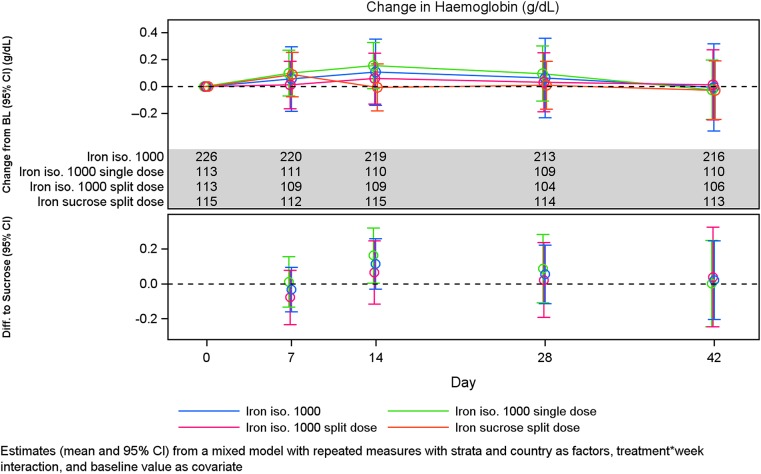

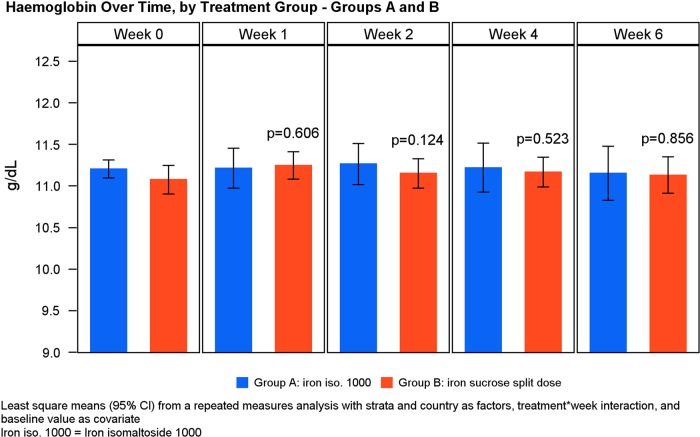

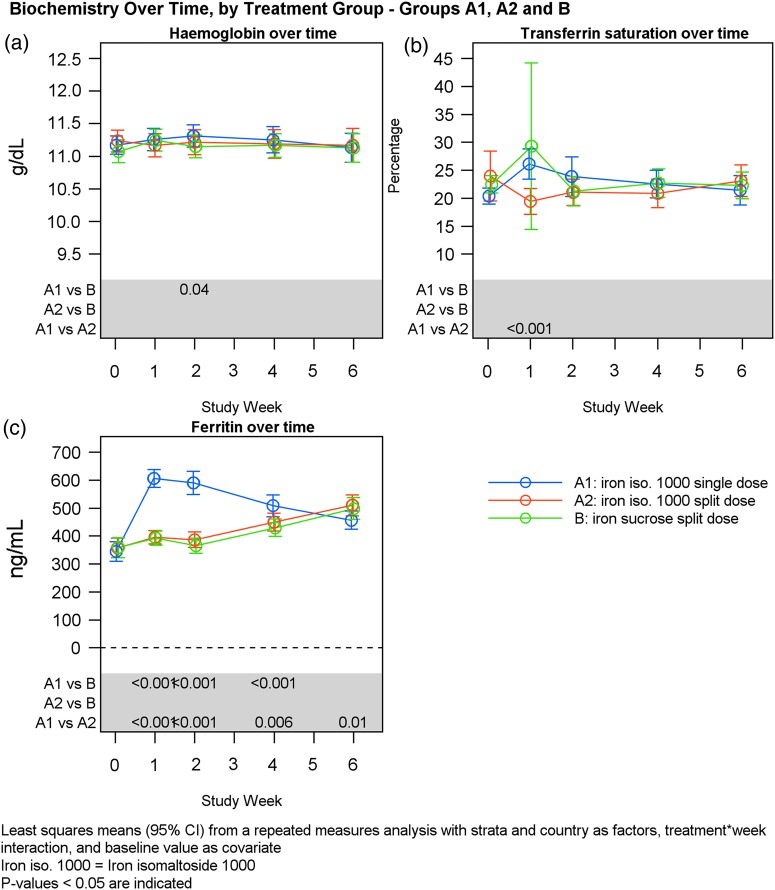

Change in Hb concentration and reticulocytes

The Hb levels and absolute change in Hb in the different treatment groups are shown in Figures 3 and 4. There was no statistical significant change in Hb concentration from baseline to Weeks 2, 4 and Week 6 between Groups A and B (Table 4, Figure 5). Similar results were observed when subgroups A1 and A2 were compared (Table 7) and when subgroups A1 and A2 were compared with Group B except at Week 2 where the increase in Hb concentration from baseline was significantly higher in subgroup A1 compared with Group B (P = 0.05) (Tables 5 and 6, Figure 6).

FIGURE 3:

Hb concentration over time by treatment group.

FIGURE 4:

Change in Hb concentration over time by treatment group.

FIGURE 5:

Hb over time by treatment group.

FIGURE 6:

Hb, serum-ferritin and TSAT over time by treatment group.

There was a statistically significant increase in reticulocyte count at Week 1 in Group A compared with Group B (P < 0.001), and similar findings were found when comparing subgroups A1 and A2 to Group B (A1 versus B: P < 0.001, A2 versus B: P = 0.02) (Tables 4 –6). No statistically significant changes in reticulocyte counts were observed from baseline to Weeks 2, 4 and 6 between Groups A and B (Table 4) and no statistically significant changes in reticulocyte counts were observed between subgroups A1 and A2 (Table 7).

Change in concentrations of serum-iron, TSAT, and serum-ferritin

There was an increase in serum-iron and TSAT concentration from baseline to Weeks 1, 2, 4 and 6 in both Groups A and B; however, no statistically significant changes were observed between the treatment groups (Table 4). At Week 1, there was a statistically significant higher increase in serum-iron in subgroup A1 compared with Group B (P < 0.001) (Table 5) and in subgroup A1 compared with subgroup A2 (P < 0.001) (Table 7). At Week 1, there was a statistically significant higher increase in TSAT in subgroup A1 compared with subgroup A2 (P < 0.001) (Table 7). Interestingly, Group B demonstrated a very wide variation in TSAT at 1 week compared with Group A (Figure 6).

There was a statistically significant increase in serum-ferritin concentration from baseline to Weeks 1, 2 and 4 in Group A compared with Group B (Weeks 1 and 2: P < 0.001; Week 4: P = 0.002) (Table 4). This difference was only evident in Group A1 (P < 0.001) but not in Group A2 (Tables 5 and 6, Figure 6). No statistically significant change in serum-ferritin concentration was observed from baseline to Week 6 between Groups A and B (Table 4). There was a statistically significant higher increase in serum-ferritin in subgroup A1 compared with subgroup A2 at Weeks 1, 2 and 4 (Weeks 1 and 2: P < 0.001; Week 4: P = 0.007) and at Week 6 it was vice versa (P = 0.01) (Table 7). A total of 9/113 (8%) and 4/113 (4%) experienced ferritinemia (i.e. >1000 ng/mL) in Groups A1 and A2, respectively. There was no statistically significant difference between the groups (P = 0.25).

Change in total QoL

The change in QoL (secondary outcomes) was conducted on the FAS (N = 341).

There was no statistically significant difference in the patient's energy level, ability to do daily activities and overall QoL between Groups A and B (Supplementary data, Table 1).

Safety

All safety analyses were conducted on the safety analysis set (N = 344).

For both iron isomaltoside 1000 and iron sucrose, the majority of the adverse events (AEs) were mild or moderate and unrelated to the trial drug. The proportion of subjects with AEs [Group A: 110/230 (47.8%); Group B: 47/114 (41.2%)] was similar (Table 8). Related AEs (i.e. ADR) were observed in 12/230 (5.2%) subjects in Group A and 3/114 (2.6%) subjects in Group B. One patient reported three ADRs. Hence, there was a total of 12 ADRs in 230 subjects (5.2%) in Group A [drug intolerance, hypersensitivity, dyspepsia, malaise, muscle spasms and paraesthesia in subgroup A1 and drug intolerance, anxiety, constipation, pruritus (2 events) and urticaria in subgroup A2] and 5 in 114 subjects (4.4%) in Group B (dry mouth, dyspnoea, chills, staphylococcal bacteraemia and limb discomfort). Of these ADRs, three were reported as serious ADRs (Group A: 1/230 (0.4%); Group B: 2/114 (1.8%); hypersensitivity in Group A and staphylococcal bacteraemia and dyspnoea in Group B. The dyspnoea and hypersensitivity reactions both occurred during the injections and were both treated as hypersensitivity reactions with administration of antihistamine and corticosteroid treatment. Vital signs were not affected and both subjects recovered completely within a short time period.

Table 8.

Summary of AEs for iron isomaltoside 1000 (single and split dose) and iron sucrose

| Number of subjects | Iron isomaltoside 1000, single dose (n = 114) | Iron isomaltoside 1000, split dose (n = 116) | Iron sucrose (n = 114) |

|---|---|---|---|

| AEs, n (%) | 51 (45) | 59 (51) | 47 (41) |

| Adverse drug reaction, n (%) | 6 (5) | 6 (5) | 3 (3) |

| Serious AEs, n (%) | 9 (8) | 13 (11) | 6 (5) |

| Serious adverse drug reactions, n (%) | 1 (<1) | – | 2 (2) |

| Suspected unexpected serious adverse reaction, n (%) | – | – | 1 (<1) |

Three subjects in Group A died during the trial and additional two subjects died between screening and randomization without being exposed to trial drug. In all cases, these events were deemed not related by the investigator and caused by other factors either in the patient's medical history/condition or in a single case a car accident. The observed mortality was in line with the expected mortality in this population in this time frame.

No differences in safety findings relating to vital signs or safety parameters between groups were observed. A low number of subjects treated with both iron isomaltoside 1000 and iron sucrose [3/230 (1.3%) versus 3/114 (2.6%)] reported hypophosphatemia defined as <2 mg/dL; however, no event was considered an AE.

DISCUSSION

The majority (82%) of subjects maintained a Hb level between 9.5 and 12.5 g/dL at Week 6, confirming that both iron preparations exhibited similar efficacy with equivalent doses. A total of 18% of the patients in both treatment Groups A and B had Hb levels outside the target range of 9.5–12.5 g/dL at Week 6, of which ∼7.5% had a Hb <9.5 g/dL and 9.6% had a Hb >12.5 g/dL (Figure 2). The mean Hb at baseline did not differ between the treatment groups and remained stable within the target range throughout the study as shown in Figure 3. The reason that some individual patients had an increase in Hb levels is probably related to the effect of iron therapy leading to improved erythron production of Hb in the 9.6% of the patients, whereas a decrease in Hb could be related to a number of factors such as bleeding, loss of a dialysis circuit from clotting and insufficient iron repletion therapy. It should be kept in mind that peripheral-iron blood indices of iron storage transport and handling have limited utility in identifying depletion of bone marrow iron stores. Even in patients with adequate bone marrow iron stores, it is sometimes possible to obtain an increase in Hb levels following iron therapy. However, this quantitative effect is lower in patients who are not iron deficient [16].

The mean serum-iron and TSAT concentrations increased from baseline to Week 6 in both treatment groups with no differences between them. Serum-ferritin initially increased more with the 500 mg single bolus compared with split dosing as one would anticipate. The maximal mean rise was observed at Week 1 with a rise up to ∼600 ng/mL followed by a steady fall towards baseline during the 6-week period. In contrast, a steady increase was observed on split dosing also by Week 6. The clinical significance of these findings for optimal dosing guidance remain speculative, but consistent with current clinical practice guidelines, serum-ferritin levels are generally lower than those found in patients with haemochromatosis where relevant tissue iron deposition starts to occur [17]. Currently, based on data from the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) Practice Monitor of 120 dialysis facilities in the USA in over a quarter of these facilities the ferritin levels exceed 800 ng/mL. Indeed, serum-ferritin concentration was at least 800 ng/mL in 34% of patients, and was >1200 ng/mL in 11% of patients [18].

A limitation of the trial is that it does not provide long-term safety data. However, it seems that the short-term safety profile of iron isomaltoside 1000 and iron sucrose are similar. The majority of the AEs in both treatment groups was mild or moderate and was unrelated to the trial drug. Three serious ADRs were reported, one on iron isomaltoside 1000 (0.4% of subjects) and two on iron sucrose (1.8% of subjects). Although iron isomaltoside 1000 demonstrated a lower percentage of serious ADRs, the trial was not powered to examine potential systematic differences in serious ADRs. Hypersensitivity reactions were rare in both groups with only one reaction requiring intervention with antihistamine and steroid in both groups. Vital signs were not affected and both subjects recovered. The present findings were analogous to other studies where both iron isomaltoside 1000 and iron sucrose showed a good safety profile in CKD patients [19, 20, 21].

An event of staphylococcal infection was considered possibly related to iron sucrose. Based on the literature, the arguments supporting relationship between IV iron and risk of infections are controversial. Several small studies in populations with CKD suggest an increased infection risk associated with IV iron therapy [22]. This association has been linked to labile iron acting as a necessary growth factor for pathogen growth [23, 24]. However, other epidemiological studies have failed to find an association between IV iron administration and infectious complications [25]. In addition, CKD is per se also associated with significant major infectious complications, which occur at rates 3–4 times the general population [26–28].

This trial only studied short-term safety. In relation to long-term safety it has recently been reported that IV iron isomaltoside 1000 and iron sucrose differ in their stability, with iron sucrose purported to release more labile iron [12]. Since some studies have linked labile iron to infections and cardiovascular morbidity, the long-term safety profile between the products might differ [29, 30].

In conclusion, this randomized trial demonstrated non-inferiority of iron isomaltoside 1000 in comparison with iron sucrose in maintaining Hb levels in subjects on haemodialysis. The safety profile of iron isomaltoside 1000 was comparable with iron sucrose and both preparations were equally tolerated with a similar short-term safety profile.

SUPPLEMENTARY DATA

Supplementary data are available online at http://ndt.oxfordjournals.org.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

All investigators/institutions received a fee per subject. S.B. received speaker and consultancy fees from Pharmacosmos A/S. P.A.K. received speaker and consultancy fees and assistance with travel from Pharmacosmos A/S, Vifor and Takeda. J.K.'s institution received research support for conducting the trial. P.A. has no further disclosure to the trial. J.H.C.'s institution received research support for conducting the trial as well as they received research support from other IV iron manufacturers. A.M.E. has no further disclosure to the trial. L.L.T. is employed by Pharmacosmos A/S. I.C.M. received consultancy fees and honoraria from Pharmacosmos A/S, as well as from other IV iron manufacturers. D.W.C. is a consultant to Pharmacosmos A/S, Vifor and Keryx, and was previously a consultant and speaker for Watson (now Actavis) and Sanofi Aventis.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors gratefully acknowledge all the investigators and trial personnel for their contribution to the trial, the statistical support from Jens-Kristian Slott Jensen, Slott Stat and the medical writing assistance of Eva-Maria Damsgaard Nielsen in editing the manuscript. Eva-Maria Damsgaard Nielsen is employed at Pharmacosmos A/S. The trial was funded by Pharmacosmos A/S.

REFERENCES

- 1.Senger JM, Weiss RJ. Hematologic and erythropoietin responses to iron dextran in the hemodialysis environment. ANNA J 1996; 23: 319–323 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Locatelli F, Aljama P, Barany P, et al. Revised European best practice guidelines for the management of anaemia in patients with chronic renal failure. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2004; 19 (Suppl 2): ii1–ii47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albaramki J, Hodson EM, Craig JC, et al. Parenteral versus oral iron therapy for adults and children with chronic kidney disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012; 1: CD007857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. KDIGO 2012 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease . 3[1], http://www.kidney-international.org (17 December 2014, date last accessed) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Bhandari S, Brownjohn A, Turney J. Effective utilization of erythropoietin with intravenous iron therapy. J Clin Pharm Ther 1998; 23: 73–78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fishbane S, Frei GL, Maesaka J. Reduction in recombinant human erythropoietin doses by the use of chronic intravenous iron supplementation. Am J Kidney Dis 1995; 26: 41–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Macdougall IC, Tucker B, Thompson J, et al. A randomized controlled study of iron supplementation in patients treated with erythropoietin. Kidney Int 1996; 50: 1694–1699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Besarab A, Frinak S, Yee J. An indistinct balance: the safety and efficacy of parenteral iron therapy. J Am Soc Nephrol 1999; 10: 2029–2043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Horl WH, Macdougall IC, Rossert J, et al. OPTA-therapy with iron and erythropoiesis-stimulating agents in chronic kidney disease. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2007; 22: iii2–iii6 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Taylor JE, Peat N, Porter C, et al. Regular low-dose intravenous iron therapy improves response to erythropoietin in haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 1996; 11: 1079–1083 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schiesser D, Binet I, Tsinalis D, et al. Weekly low-dose treatment with intravenous iron sucrose maintains iron status and decreases epoetin requirement in iron-replete haemodialysis patients. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2006; 21: 2841–2845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jahn MR, Andreasen HB, Futterer S, et al. A comparative study of the physicochemical properties of iron isomaltoside 1000 (Monofer), a new intravenous iron preparation and its clinical implications. Eur J Pharm Biopharm 2011; 78: 480–491 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zager RA, Johnson AC, Hanson SY, et al. Parenteral iron formulations: a comparative toxicologic analysis and mechanisms of cell injury. Am J Kidney Dis 2002; 40: 90–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zager RA, Johnson AC, Hanson SY. Parenteral iron nephrotoxicity: potential mechanisms and consequences. Kidney Int 2004; 66: 144–156 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. European Medicine Agency. New recommendations to manage risk of allergic reactions with intravenous iron-containing medicines, EMA/377372/2013, 28 June 2013

- 16.Stancu S, Barsan L, Stanciu A, et al. Can the response to iron therapy be predicted in anemic nondialysis patients with chronic kidney disease? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2010; 5: 409–416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wish JB. Assessing iron status: beyond serum ferritin and transferrin saturation. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 2006; 1 (Suppl 1): S4–S8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pisoni RL, Fuller DS, Bieber BA, et al. The DOPPS practice monitor for US dialysis care: trends through August 2011. Am J Kidney Dis 2012; 60: 160–165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aronoff GR, Bennett WM, Blumenthal S, et al. Iron sucrose in hemodialysis patients: safety of replacement and maintenance regimens. Kidney Int 2004; 66: 1193–1198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gupta DR, Larson DS, Thomsen LL, et al. Pharmacokinetics of iron iromaltoside 1000 in patients with stage 5 chronic kidney disease on dialysis therapy. J Drug Metab Toxicol 2013; 4: 152 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wikstrom B, Bhandari S, Barany P, et al. Iron isomaltoside 1000: a new intravenous iron for treating iron deficiency in chronic kidney disease. J Nephrol 2011; 24: 589–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maynor L, Brophy DF. Risk of infection with intravenous iron therapy. Ann Pharmacother 2007; 41: 1476–1480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bullen JJ, Rogers HJ, Spalding PB, et al. Natural resistance, iron and infection: a challenge for clinical medicine. J Med Microbiol 2006; 55: 251–258 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nairz M, Schroll A, Sonnweber T, et al. The struggle for iron – a metal at the host-pathogen interface. Cell Microbiol 2010; 12: 1691–1702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoen B, Paul-Dauphin A, Kessler M. Intravenous iron administration does not significantly increase the risk of bacteremia in chronic hemodialysis patients. Clin Nephrol 2002; 57: 457–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fuller DS, Pisoni RL, Bieber BA, et al. The DOPPS practice monitor for US dialysis care: trends through December 2011. Am J Kidney Dis 2013; 61: 342–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brookhart MA, Freburger JK, Ellis AR, et al. Infection risk with bolus versus maintenance iron supplementation in hemodialysis patients. J Am Soc Nephrol 2013; 24: 1151–1158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Naqvi SB, Collins AJ. Infectious complications in chronic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 2006; 13: 199–204 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuo KL, Hung SC, Lee TS, et al. Iron sucrose accelerates early atherogenesis by increasing superoxide production and upregulating adhesion molecules in CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 2014; 25: 2596–2606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fell LH, Zawada AM, Rogacev KS, et al. Distinct immunologic effects of different intravenous iron preparations on monocytes. Nephrol Dial Transplant 2014; 29: 809–822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.