Preface

Animal development requires a carefully orchestrated cascade of cell fate specification events and cellular movements. A surprisingly small number of choreographed cellular behaviours are used repeatedly to shape the animal body plan. Among these, cell intercalation lengthens or spreads a tissue at the expense of narrowing along an orthogonal axis. Key steps in the polarization of both mediolaterally and radially intercalating cells have now been clarified. In these different contexts, intercalation seems to require a distinct combination of mechanisms, including adhesive changes that allow cells to rearrange, cytoskeletal events through which cells exert the forces needed for cell neighbour exchange, and in some cases regulation of these processes through planar cell polarity.

Developmental biologists have been fascinated by how an embryo is able to generate its shape—through morphogenesis—for centuries1. Successful development requires both proper fate specification and proper movements of cells, two processes that are often intricately interdependent. Cell intercalation is one of these movements, and crucially depends on highly directed exchanges between neighbouring cells, without a change in overall cell number. This can occur early in development, when the germ layers are organized during gastrulation, or later during organogenesis if a particular tissue requires an extended morphology (Figure 1A).

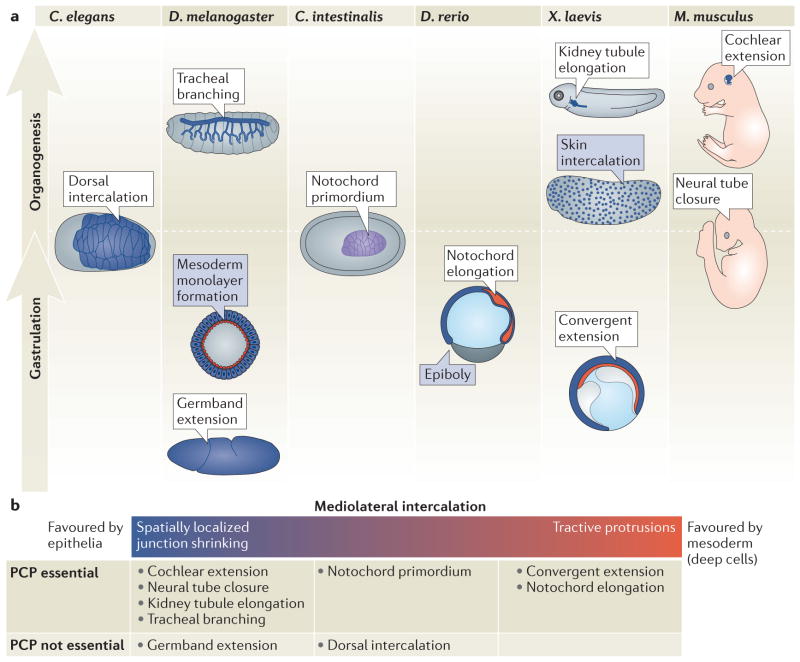

Figure 1. Intercalation events drive morphogenesis in diverse contexts during metazoan development.

a, Intercalation events promote morphogenesis during distinct stages of development, including gastrulation and organogenesis (shown vertically in the figure). These include mediolateral intercalation events (in white boxes) and radial intercalation events (blue boxes). In all figures, epithelial structures are in blue; mesodermal structures are in red; endoderm structures are not shown. The C. intestinalis (ascidian) notochord is unusual in that it behaves as an epithelium early and later like a non-epithelial mesoderm, and thus is shown in purple. Embryos are shown laterally with anterior to the left and posterior to the right, except C. elegans and C. intestinalis which are shown as dorsal views, the Drosophila mesoderm, which is shown as a cross-sectional view, and the mouse embryo, which is shown as anterior up and posterior down. b, Mediolateral intercalation can be driven by different cellular programmes. Many epithelia undergo cell intercalation through tight regulation of their apical junctions, whereas many mesodermal cells undergo intercalation through basolateral protrusive activity. However, these mechanisms may represent two poles along a continuum, with some intercalation events displaying only some characteristics of each pole. The different intercalation events are listed below, at a position that reflects the mechanisms that drive mediolateral intercalation in this context. Only a subset of these require planar cell polarity (PCP) signalling.

Depending on its direction, intercalation can drive a variety of morphogenetic events. Mediolateral intercalation, in which cells exchange places with one another within the same plane, underlies convergent extension during diverse developmental processes, from the extension of the body axis during gastrulation in flies and frogs to the elongation of epithelial tubes such as the fly trachea or the vertebrate kidney and cochlea (Figure 1). There are multiple other mechanisms that can drive tissue elongation2, but cell intercalation is unique in requiring that the migration and adhesion of many cells are coordinated in time and space to change the shape of a tissue. Radial intercalation, in which cells exchange places throughout the thickness of a multilayered tissue, can drive tissue spreading, or epiboly. Radial intercalation occurs during frog and fish gastrulation, as well as during thinning of the ventral mesoderm in Drosophila and development of skin in frogs (Figure 1A).

The molecular mechanisms that orchestrate this process have been characterized and include common factors such as cadherins, non-muscle myosin and RhoGTPases. However, although both epithelial and mesodermal cells use this machinery to undergo mediolateral intercalation, they execute this in very different ways. For all cell types, successful mediolateral intercalation requires that cells are polarized, and thus rearranging cells often rely on the planar cell polarity (PCP) pathway that drives polarization of cells within the plane of the tissue (Box 1). By contrast, cells that intercalate radially often do not seem to depend on PCP signals (for reviews of cell intercalation control by PCP signalling, see references 3–7). In this Review, we take an integrated approach to intercalation and highlight the regulatory mechanisms that are common between diverse intercalation behaviours of epithelial and mesodermal cells. Although there are notable exceptions, in general, mediolateral intercalation programmes depend on tissue type, with epithelial cells relying on their inherent apical junctions and mesodermal cells requiring tractive basolateral protrusions. Radial intercalation programmes seem to be more context-specific and often require non-autonomous signals.

Box 1. Planar Cell Polarity (PCP) signalling promotes tissue polarity.

The planar cell polarity pathway orients tissues within a single plane, orthogonal to any apicobasal polarity. PCP signalling was first discovered to align hairs in the Drosophila wing disc124,125, but has since been found to broadly coordinate cell extensions and cell movements between neighbouring cells in the same plane. Many of the key members of the PCP pathway are transmembrane and membrane-associated. The core transmembrane players include: the seven-pass transmembrane Wnt receptor, Frizzled; the four-pass transmembrane receptor Van gogh/Strabismus; and the atypical cadherin, Flamingo/Starry Night/Celsr. The core cytoplasmic proteins are the PDZ, DIX, and DEP-domain-containing protein, Dishevelled (Dsh); the LIM and PET domain-containing protein, Prickle, and the ankryin repeat protein, Diego. Flamingo can recruit either Frizzled or Van gogh, which in turn can recruit Dishevelled and Prickle, respectively126. Dishevelled interacts competitively with Prickle and Diego. Whereas Diego promotes Frizzled signalling through Dishevelled, Prickle inhibits it127. These core PCP components are often asymmetrically localized in cells. Thus, depending on the localization of these Dishevelled interactors, the pathway may be inhibited or activated in certain sites within a cell. When PCP signalling is active, it can locally activate both Rho and Rac signalling to bring about actomyosin-mediated cytoskeletal changes. Polarization of both epidermal and mesodermal tissues seems to depend on the PCP pathway. Barring a few exceptions10,50, the PCP pathway coordinates most mediolateral intercalation events observed so far; its role during radial intercalation events is less clear. Consistent with its requirement during vertebrate gastrulation62, human mutations in PCP pathway components lead to neural tube defects120,122,128, highlighting the phylogenetic conservation of this pathway.

From the top: the apical epithelium

We begin with mediolateral intercalation programmes in epithelia. As differentiated epithelial cells have a strict apicobasal polarity, we first consider events that occur at cell apices and then processes that occur more basally. Through apical adherens junctions, neighbouring cells adhere to one another via homophilic binding of cadherins; this binding is transduced to the cytoskeleton via β-catenin and α-catenin to F-actin (reviewed in 8). In multiple systems, actomyosin remodelling of specific adherens junctions drives cell intercalation of epithelial sheets. However, intercalating epithelial cells in certain systems can also extend basolateral protrusions, which may represent a different intercalation mechanism.

Apical junction shrinkage in epithelia

Intercalation places unique demands on adherens junctions: during active cell rearrangement, cells must maintain adhesion but also retain the ability to move. To meet these demands, many rearranging epithelial cells shrink junctions that are oriented perpendicular to the axis of extension and subsequently resolve such shrinkage to restore more isodiametric shapes. Here we consider several examples of this common mechanism and how it is controlled, from fly gastrulation to the extension of epithelial tubes in vertebrates.

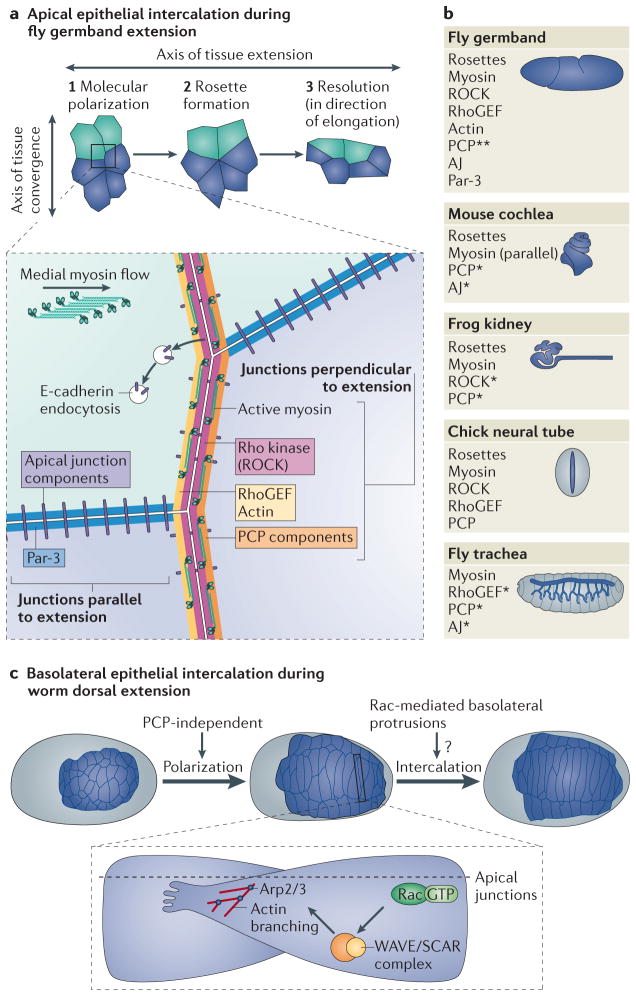

Apical junction shrinkage during fly germband extension

The shortening of epithelial junctions during mediolateral intercalation has been extensively described in the gastrulating Drosophila embryo, during a process known as germband extension (GBE)9–15 (Figure 2A). As the prospective mesoderm and endoderm are being internalized, the outer, columnar ectoderm (the germband) doubles its length along the anterior-posterior axis and halves its width along the dorsoventral axis within 2 hours9. The massive extension of the germband arises from the intercalation of cells along the dorsal-ventral axis9,11, with minor contributions via oriented cell division16–18. As the germband extends, the anterior and posterior (‘vertical’) edges of cells shrink. This key event is driven by actomyosin-mediated constriction, as both inhibition11 or mutation of myosin19, or inhibition of a major activator of myosin contraction, Rho kinase (ROCK), block intercalation and GBE11 (Box 2). Non-muscle myosin II10,11, F-actin12, ROCK19, and RhoGEF220 accumulate specifically at shrinking vertical boundaries. By contrast, shotgun/E-cadherin, armadillo/β-catenin, and bazooka/Par3 accumulate in a complementary pattern, at dorsoventral (‘horizontal’) boundaries10,12,20. E-cadherin seems to be excluded from vertical boundaries by endocytosis downstream of RhoGEF220. β-catenin is also quickly turned over at vertical boundaries due to its phosphorylation downstream of Abl kinase21. Together, these two mechanisms contribute towards decreased adhesion at vertical junctions, and actomyosin constriction then directs their shrinkage.

Figure 2. Intercalation in epithelial cells can be driven through junction remodelling or protrusion formation.

a, During germband extension in D. melanogaster, epithelial mediolateral intercalation relies on shrinkage of junctions that lie perpendicular to the axis of extension. Junction disassembly often results in rosette formation, which resolves in the direction of tissue extension. Cartoon cells were traced from live images of GBE cells, available at http://www.hhmi.org/research/molecular-control-polarized-cell-behavior. Junctions parallel to the direction of extension are enriched for apical junction components and Par-3 (inset). By contrast, junctions perpendicular to the direction of tissue extension are enriched for planar cell polarity (PCP) components, and shrinking of these junctions is driven by myosin, and—in some cases—cadherin. Non-muscle myosin II, F-actin, ROCK and RhoGEF2 all accumulate specifically at shrinking vertical junctions. E-cadherin endocytosis occurs at perpendicular junctions, which may contribute to reduced adhesion there. Medial myosin flow also correlates with junction shrinkage. Comparison between intercalation events during fly germband extension and in epithelial tubes, including the mouse cochlea, frog kidney, chick neural tube, and fly trachea. An asterisk (*) indicates that a requirement for that component has been demonstrated, but its junctional polarization has not yet been determined and a double asterisk (**) indicates that the component has a polarized distribution, but is not required for intercalation. The remaining factors shown seem to be both required and asymmetrically polarized. All the systems shown, except the fly trachea, require rosette formation for intercalation. c, Basolateral protrusion formation during dorsal intercalation in C. elegans. Cells extend tips towards the midline and basal to the apical junctions, through Rac-dependent regulation of actin branching via the nucleating complex Arp2/3. Intercalation is completed once the tips reach the lateral (seam) cell on the contralateral side. Polarization of these cells appears to be PCP-independent.

Box 2. Non-muscle myosin II structure and regulation.

Non-muscle myosin II (NMII) is a major regulator of the actomyosin network in non-muscle cells. It is a hexamer made up of two homodimerized heavy chains, two regulatory light chains (MRLC), and two essential light chains (see the figure). The motor activity, which allows NMII to move filamentous actin, resides in the head domain of the heavy chain. Motor activity is induced by phosphorylation of the regulatory light chains, which can occur via multiple pathways, most notably the Rho pathway, whose effector is Rho-associated kinase (ROCK). The heavy chain also can be regulated by post-translational modification of the tail domain, a region that is required for the assembly of multimeric NMII filaments. Movement along assembled filaments is thought to be the major mechanism of actin translocation. High-speed imaging of either heavy or regulatory light chain subunits has revealed that myosin accumulates in pulses during intercalation15,23,129. However, myosin pulses may occur ubiquitously and only be capable of mediating cell shape changes when they are linked to apical junctions130. In this review we refer to NMII simply as ‘myosin.’

One straightforward hypothesis is that the anterior-posterior localized (vertical) junctional pool of myosin shrinks junctions via formation of multicellular contractile networks along the dorso-ventral axis10–14,19. The situation may be more complex than this, however. Dynamic imaging shows that peak levels of myosin occur medially, away from junctions, prior to its accumulation at vertical junctions. Ablating the medial pool of myosin perturbs junction shrinkage15 and high-speed filming indicates oscillatory shrinkage of anterior and posterior edges of intercalating cells. As cell edges shrink, myosin flow outward toward junctions correlates inversely with E-cadherin levels at particular junction boundaries: greater flow occurs toward vertical junctions with less E-cadherin in normal and experimentally manipulated embryos22. If non-junctional myosin contributes to intercalation via a physical linkage to junctions that permits variable slippage, then the apical actomyosin cortex must presumably physically link to adherens junctions in a spatially anisotropic fashion. One possible linker is canoe/Afadin, which is required during GBE to link E-cadherin to the actin cytoskeleton23. It will be important to assess the relative importance of junctional and non-junctional pools of myosin, but this ultimately awaits methods that can selectively perturb one pool and leave the other intact.

Polarized accumulation of activated myosin at shrinking boundaries is a hallmark of GBE. This implies that, in addition to apicobasal polarity, cells must also be polarized within the plane of the epithelium during intercalation. Indeed, the well conserved planar cell polarity (PCP) pathway (Box 1) is required for polarization of epithelia and also mesodermal cells deeper in the embryo during intercalation. The PCP pathway regulates the planar polarized accumulation of some, but not all, proteins during GBE10,24. However, at least one additional pathway is probably required for the complete planar polarization of the germband, as neither the Wnt receptor, Frizzled, nor a major Wnt effector, Dishevelled, are required for GBE10,24. This may involve anterior-posterior patterning, which is required for planar polarization of the germband9.

The distribution of junctional proteins indicates that cells are polarized prior to neighbour exchange in the germband. The distribution of myosin and adherens junction components in particular further indicates how physical neighbour exchange might occur. Constriction of the vertical edges of cells in the germband could lead to eventual shortening of these boundaries, resulting in the dorsoventral movement of these cells and GBE. The detailed mechanisms by which cells resolve localized junctional shrinkage may depend on the number of cells engaged in shrinkage in any local region of the germband. In some cases, local remodelling of junctions where two cells abut might lead to shrinkage of the vertical boundary between them, as cells above (dorsal) and below (ventral) the pair intercalate between them11. In many cases, however, a more regional mechanism of junction resolution seems to predominate: through the organization of neighbouring epithelial cells into multicellular ‘rosettes’12,14. In such instances, multiple intercalating cells form flower-shaped structures14, and eventual resolution of these rosettes in the direction of tissue extension is a major driving mechanism of tissue extension12 (Figure 2A). A key question is what controls rosette formation. The constriction of intercellular myosin cables is probably crucial, as there are defects in rosette formation in spaghetti squash/myosin regulatory light chain (MRLC) mutants19. Genetic perturbation of anterior-posterior patterning of the germband still allows rosettes to form, but they either resolve randomly or more slowly than in wild-type embryos12. Thus, myosin itself seems to contribute towards rosette establishment and anterior-posterior patterning directs rosettes to resolve in a direction that effectively extends the tissue.

In conclusion, the fly germband is a well-studied model of epithelial intercalation that does not strictly require PCP signalling, but in which actomyosin-mediated shrinkage and E-cadherin endocytosis contribute to junction collapse (often forming rosette structures) in the direction of tissue convergence and resolution in the direction of tissue extension.

Apical junction shrinkage during tubule elongation

Rosette formation followed by resolution in the direction of tissue extension has also been shown to drive mediolateral intercalation of cells during the extension of various tubes, including: the chick neural tube25,26; renal tubules in mouse27 and Xenopus28; the cochlea of the mammalian inner ear29–31; and tracheal tubes in Drosophila (Figure 2A, right). Actomyosin-mediated shrinkage of vertical junctions in the neural tube25,26 and renal tubules27,28 closely resembles that in the germband. The cochlea resembles the germband in that it forms rosettes, though the role of the actomyosin network may be more complex, as components are not polarized similar to other systems30,31. The fly trachea further highlights the importance of E-cadherin endocytosis during intercalation24, also observed during GBE. In general, PCP signalling seems to have a more prominent role in polarizing intercalating cells of these tissues than in the germband.

During chick neural tube development, shortly after gastrulation, the neuroepithelium undergoes mediolateral intercalation. This convergent extension movement is required to decrease the width of the neuroepithelium, thereby aiding neural fold elevation at the dorsal midline and hence neural tube closure. In the chick and mouse, mediolateral intercalation of the neuroepithelium has similarities to GBE in Drosophila25. Approximately 30% of cells in the neuroepithelium are found in rosettes, which resolve to extend the tissue26. As in GBE, mediolateral intercalation of the neuroepithelium in chick26 and mouse32 requires ROCK. In the chick, ROCK is required for junction shrinkage and is recruited to adherens junctions perpendicular to the axis of extension; phosphorylated MRLC likewise accumulates at these junctions25,26. Unlike during GBE, however, there is a strict requirement for all of the canonical components of the PCP pathway in neural tube closure: Celsr/Flamingo and Dishevelled are polarized similarly to ROCK25. Notably, the localization of PDZ-RhoGEF is also planar polarized in the neuroepithelium, much like that of the homologous protein RhoGEF2 in the Drosophila germband. PDZ-RhoGEF has been proposed to activate myosin to aid constriction25, but in this case it has not yet been addressed whether PDZ-RhoGEF may also be contributing to junction shrinkage by mediating E-cadherin endocytosis, as occurs during GBE.

The collecting ducts associated with the vertebrate kidney are elongated tubes required for proper reabsorption of fluid, whose morphogenesis occurs in the embryo. Cell division probably does not contribute significantly to duct extension27,33; instead, cells elongate perpendicular to the axis of extension, a hallmark of intercalation behaviour27. Direct evidence for intercalative behaviour was recently provided28. The molecular pathways involved seem similar to those used during GBE and in the chick neuroepithelium. Not only do renal cells from both mouse27 and Xenopus require ROCK and show mediolateral polarization of phosphorylated MRLC 28, but ~40% of renal cells are also part of rosettes, which resolve along the proximal-distal axis of tissue extension28. Unlike during GBE, it is clear that the major canonical components of PCP signalling are required to orient rosettes and tissue extension in the renal system27,28. The kidney provides an interesting case in which adjustment of intercalation behaviour may have potential application in treating disease. Polycystic kidney disease (PKD) is a strikingly common disorder in humans that results in cyst formation, initially in nephrons, typically later in life 34. In mice carrying mutations known to cause PKD, cysts no longer form under conditions that favour excessive intercalation during development33. These results raise the intriguing possibility that activation of the intercalation programme could ameliorate formation of kidney cysts28.

Hearing in the mammalian inner ear is mediated by the cochlea, a long, thin, coiled tube in which pressure waves are transduced into neuronal signals. The cochlea arises from a primordium called the cochlear duct, which decreases in width and depth and increases in length during development, suggesting that both mediolateral35 and radial intercalation36 may be involved in cochlear morphogenesis. PCP seems to be required both for convergent extension and the polarity of mechanosensory hair cells within the epithelium29. Although myosin is required for mediolateral intercalation in the inner ear, it is localized mainly parallel to the axis of tissue extension30, in stark contrast to the other examples mentioned here. This localization is inconsistent with a role in junction shrinkage. Instead, a component of the cadherin-catenin-complex, p120 catenin, and the PCP component, Van Gough/Strabismus, seem to regulate cadherin expression31. Moreover, rosettes form within the cochlea31, suggesting that either a separate mechanism is causing rosette formation, or unidentified myosins are at work.

The Drosophila tracheal system is an extensively ramified tubular network required for gas exchange in the larva and adult. During development, tracheal cells develop from the embryonic epidermis (~11 hrs after GBE). The tracheal system consists of a dorsal trunk with a wide circumference, due to the activity of transcription factors that inhibit intercalation, and dorsal branches, which are transcriptionally activated to intercalate extensively37–39. Similarly to the germband, intercalation in the Drosophila trachea requires proper trafficking of E-cadherin. Too much or too little junctional E-cadherin inhibits intercalation40. However, unlike the germband, in which endocytosis is polarized and largely confined to disassembling junctions, in tracheal cells there is no intracellular polarization of E-cadherin endocytosis24. Instead, junctional E-cadherin is internalized in intercalating cells (dorsal branches) but remains high in non-intercalating (dorsal trunk) cells. In addition to endocytosis, E-cadherin activity is finely tuned by two antagonistic roles of the non-receptor tyrosine kinase, Src. Active, phosphorylated Src not only decreases E-cadherin protein accumulation, allowing cells to move; it also directs new transcription of E-cadherin through the Wnt/β-catenin pathway, providing enough E-cadherin to maintain normal epithelial integrity41. In addition to E-cadherin regulation, tension produced along the direction of tissue extension by actively migrating cells at the tips of dorsal branches is required for successful intercalation42. Although there is a clear role for myosin much earlier in tracheal development43, little is currently known about myosin function during the intercalations associated with tracheal branching. Tracheal intercalation requires the core PCP pathway and RhoGEF2 to properly regulate E-cadherin endocytosis at junctions24.

In summary, ectodermal sheets and epithelial tubes show striking similarities in the mechanisms that drive cell intercalation. Except for the fly trachea, most closely resemble fly GBE, in that polarized myosin mediates junction collapse into rosette structures that resolve to mediate intercalation. One notable exception is the cochlea, in which myosin aligns orthogonally relative to other systems. Understanding what controls junction collapse in this system will be especially interesting. It will also be important to understand what role, if any, E-cadherin endocytosis might have in these contexts. The fly trachea, on the other hand, seems to rely heavily on non-polarized down-regulation of cell adhesion through E-cadherin endocytosis, an event also seen during mesodermal mediolateral intercalation. Unlike the germband, in all cases of epithelial tubes studied so far, PCP signalling is strictly required.

Going deeper: the basal epithelium

Studies of epithelial cell rearrangement have focused predominantly on the apical surface. But such analysis may be incomplete. For example, dynamic imaging of the germband of Drosophila has not been carried out in three dimensions, and concurrent basolateral motility may have been missed. Moreover, in other epithelia including the dorsal epidermis of the C. elegans embryo and the ascidian notochord primordium, basolateral protrusive activity is prominent. This suggests that, in certain contexts, basolateral protrusions are important for epithelial mediolateral intercalation and may represent an alternative mechanism, more akin to mesodermal mediolateral intercalation.

Basolateral motility during dorsal intercalation in C. elegans

Studies of the worm dorsal epidermis have provided insights into the contribution that intercalation can make during tissue morphogenesis. During formation of the dorsal midline, two rows of epidermal cells intercalate to form a single row (Figure 2B). Cells initially become wedge-shaped as their medial tips point towards the dorsal midline. They then interdigitate between their contralateral neighbours, until contact is made with lateral epidermal (seam) cells on the contralateral side of the embryo44,45. The nuclei of intercalating cells also move contralaterally44,45, an indication that the microtubule cytoskeleton is polarized along the mediolateral axis46. However, nuclear migration is not required for successful intercalation47.

Dorsal cells extend highly polarized basolateral protrusions in the direction of rearrangement, which lie just beneath, or basal, to apical junctions 45,48. These protrusions are highly dynamic (E. Walck-Shannon and J. Hardin, unpublished observations). Rac signalling, presumably acting through the actin-nucleating Arp2/3 complex via the WAVE complex, is constitutively required for intercalation49, but what guides these protrusions, and how they are coupled to junction rearrangement is unknown. Laser ablation experiments indicate that intercalation of dorsal cells is locally autonomous, and does not crucially depend on the presence of defined neighbours45,48 (R. King and J. Hardin, unpublished). The C2H2 Zinc finger transcription factor, DIE-1, is also required for completion of dorsal intercalation, but not for the initial polarization of intercalating cells towards the dorsal midline48. There is no clear evidence for a PCP pathway in C. elegans, and conserved PCP components do not appear to regulate dorsal intercalation; disruption of Dishevelled function results in lineage defects prior to intercalation50. Dorsal intercalation therefore illustrates that additional, non-PCP-mediated polarity cues may operate in some cases of epithelial mediolateral intercalation. It also confirms the key role of the Rac pathway in producing the protrusions that are characteristic of this mode of epithelial intercalation.

Basolateral motility of the ascidian notochord primordium

The notochord in ascidian embryos arises from an epithelial primordium of exactly 40 cells, which is internalized via invagination. It is difficult to know how to characterize the ascidian notochord. In this Review, we address it in both the epithelial and mesodermal sections. While it is still a monolayer, the cells of the notochord primordium behave as an epithelium as they undergo mediolateral intercalation. Ultimately, however, the notochord forms a mesodermal, rod-shaped primordium strikingly similar to that in other chordates. As the cells in the initial notochordal primordium intercalate, cells extend broad protrusions along most of the apicobasal axis (Figure 3a) 51. Several lines of evidence indicate that PCP signalling is required for successful intercalation of these cells. Expression of dominant-negative Dishevelled constructs that are predicted to disrupt PCP leads to cell-autonomous defects in intercalation in Ciona intestinalis52. In C. savignyi, Dishevelled is asymmetrically localized at the cortex of presumptive notochord cells at their boundary with presumptive muscle; cells internal to the notochord primordium do not show such asymmetry, suggesting that the boundary with muscle may constitute a polarizing cue. The asymmetric distribution of Dishevelled is lost in the aimless/Prickle mutant, and presumptive notochord cells lose mediolateral bias to their protrusions without an overall decrease in protrusive activity53. Recent data indicate that, in addition to mediolateral polarization, apicobasal polarity of presumptive notochord cells is also important for intercalation. In C. intestinalis, atypical protein kinase C (aPKC) is expressed apically, whereas laminin is initially expressed basally within the monolayer. Later, as the notochord becomes a solid rod, both aPKC and laminin subunits redistribute54. Overexpression of a dominant-negative form of the ephrin Eph4 disrupts this polarization and leads to defective intercalation, whereas apicobasal polarity is not disrupted by dominant-negative Dishevelled constructs. One caveat that complicates the interpretation of these experiments is that dominant-negative Eph4 constructs also alter cleavage orientation of notochord precursors54. Nonetheless, these experiments point to a key relationship between the apicobasal axis of epithelial cells and whatever spatial cues are mediated via the PCP pathway.

Figure 3. Mediolateral intercalation of deep mesodermal cells in vertebrates.

a, Ascidian notochord intercalation requires both planar cell polarity (PCP) and the basement membrane. Cells in the notochord primordium, which is initially epithelial (purple), extend basolateral protrusions (BLPs) along the apico(A)-basal(B) axis (left, inset). The notochord eventually behaves more like mesoderm and is polarized by the PCP pathway, which works in parallel to the basement membrane to direct completion of intercalation.

b, Mesodermal mediolateral intercalation requires downregulation of C-cadherin. In the example shown here, during chordamesoderm convergent extension in a frog Keller explant, cells extend bidirectional, mediolateral protrusions, which provide traction for cell intercalation towards the midline. Inset: At the mediolateral ends of intercalating cells, PAPC and Frizzled bound to C-cadherin inhibit cell adhesion by inhibiting C-cadherin clustering, while both PAPC and the PCP pathway help to activate cytoskeletal extensions through regulation of the RhoGTPases Rac and Rho and Arp2/3-mediated actin nucleation. PAPC may activate Rho by inhibiting the transcription of Rho GAPs. PAPC that is not bound to Frizzled undergoes endocytosis. The extracellular matrix (ECM) component fibronectin (FN) also signals to more apical pathways through interactions with integrin and synedcan. c, Later phases of mediolateral intercalation in the notochord. Boundary formation requires laminin β1 and γ1 in zebrafish (yellow) and completion of intercalation requires the PCP pathway. The PCP components Prickle and Dishevelled (Dsh) localize to puncta at the anterior (A) and posterior (P) sides of the cell, respectively (inset, right).

Together, these examples illustrate that the basolateral portion of an epithelial cell can make important contributions during mediolateral intercalation, and beg the question of whether such basal protrusions might have a more widespread role during epithelial intercalation driven by junctional rearrangement than previously appreciated. On the other hand, this could suggest that epithelia have the ability to pursue a spectrum of intercalation programmes; it will be interesting to understand why each is favoured in certain contexts.

Deeper still: non-epithelial cells

Unlike epithelia, deep mesodermal cells in vertebrate embryos do not have a strictly defined apicobasal axis, and need not be tightly associated with their neighbours. Although common themes have emerged regarding the overall patterns of vertebrate mesodermal migration, it is unclear to what extent mesodermal cells in various vertebrate gastrulae behave as genuine tissues. Most mesodermal and endodermal cells of the zebrafish gastrula, for example, undergo directed migration individually (for an in-depth review, see reference 55). By contrast, biomechanical measurements of amphibian deep cells indicate that they have well-defined, aggregate mechanical properties56,57.

Generating protrusions during frog convergent extension

Mechanisms of deep mesodermal intercalation have been most extensively studied in the dorsal involuting marginal zone (DIMZ) of the Xenopus gastrula (Figure 3b). After involution through the blastopore, a part of the DIMZ called the chordamesoderm undergoes mediolateral intercalation. As is true for many epithelia, intercalating chordamesodermal cells are elongated perpendicular (mediolaterally) relative to the axis of extension (along the anterior-posterior axis). Much of what is known about their detailed behaviour has been gleaned from Keller explants58, which allow direct observation of intercalating cells.

Mediolateral intercalation in chordamesoderm arises from protrusive activity that becomes polarized to the medial and lateral tips of intercalating cells59. Such protrusions are thought to be ‘tractive’, that is, they attach to neighbouring intercalating cells and provide traction for cellular movement. Indeed, actomyosin networks that interconnect these putative tractive foci go through pulses of contraction during intercalation and cell elongation, which may drive cell shape change60. Foci maintenance and pulsatile dynamics, and normal protrusive activity depend on myosin II60,61. So, although myosin II has a role in both epithelial and mesodermal intercalation, its function in these contexts varies; whereas it mediates junction shrinkage in some epithelia, it mediates tractive, protrusive activity in deep mesoderm.

Similarly to epithelia, intercalating mesodermal cells are polarized. Rather than designating certain junctions for disassembly, however, the PCP pathway seems to polarize protrusive tips of intercalating mesodermal cells62. Dishevelled is localized to these protrusions, along with actin and some of its regulators including Arp2/3 and the GTPase Rac63. More surprisingly, there are many other molecules localized to these tips, including the polarity proteins Par-5, Par-6 and aPKC64. It is clear that these proteins affect intercalation, but it is not known whether their localization to tips is absolutely required. In fact, polarized Dishevelled localization may actually be an artifact of yolk distribution within chordamesodermal cells65.

Regulating cell adhesion during frog convergent extension

Both cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix interactions regulate intercalating DIMZ cells (Figure 3b; Table 1). Either too much or too little C-cadherin66 prevents normal intercalation, suggesting that tight regulation of C-cadherin is required for proper intercalation67,68. C-cadherin expression is ubiquitous, so it must presumably act alongside other localized proteins. One candidate is paraxial protocadherin (PAPC), the expression of which is restricted to the chordamesoderm during intercalation69,70, and is required for convergent extension71. PAPC has no intrinsic adhesive function72 but disrupts C-cadherin-mediated adhesion72. It also localizes to protrusive tips of intercalating cells71, but this needs to be confirmed given the recent finding that yolk distribution is uneven in chordamesodermal cells65. If true, however, such preferential PAPC localization further supports a model in which PAPC might downregulate C-cadherin activity at these tips, where it presumably works together with PCP signalling to promote convergent extension.

Table 1.

Extracellular Matrix Requirements for Intercalation.

| ECM Components | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Component | Tissue(s) | Intercalation type | Reference(s) |

| Laminin | Ascidian and zebrafish notochord | mediolateral | 54, 89, 93 |

| Fibrillin | Frog gastrula mesoderm | mediolateral | 92 |

| Fibronectin | Frog gastrula mesoderm | mediolateral | 80, 81 |

| Frog deep ectoderm | radial | 82 | |

| Receptors | |||

| Receptor | Tissues(s) | Intercalation type | Reference(s) |

| Integrins | Frog gastrula mesoderm | mediolateral | 80, 81 |

| Frog deep cell ectoderm | radial | 82 | |

| Zebrafish notochord | mediolateral | 94 | |

| Syndecan | Frog gastrula mesoderm | mediolateral | 82, 83 |

| Dystroglycan* | Frog skin | radial | 117 |

appears to act cell non-autonomously

Although PAPC and PCP signalling62,73,74 are separately required for convergent extension71, they appear to interact. PAPC and C-cadherin can each form separate complexes with Frizzled7 when it is bound to Wnt11, and both complexes can downregulate C-cadherin-based adhesion. Whereas free PAPC is constitutively endocytosed, PAPC bound to Frizzled7 accumulates at junctions and prevents strong C-cadherin-based adhesion by inhibiting C-cadherin clustering. C-cadherin binding to Frizzled7/Wnt11 also inhibits C-cadherin-based adhesion independently of PAPC; in this case, C-cadherin/Frizzled7/Wnt11 competes with cis dimerization of unbound C-cadherin75 (Figure 3b, inset). Beyond its role in inhibiting C-cadherin, PAPC also influences Rho family GTPases. Although it is unclear how it does this, PAPC has been reported to inhibit Rac and activate the Rho and JNK pathways71. It may do so by enhancing PCP signalling through sequestration of a protein that indirectly inhibits PCP, Sprouty76,77. Alternatively, PAPC may activate Rho by triggering the transcriptional downregulation of two GAPs, xGit1 and RhoGAPIIA, in intercalating cells78.

In addition to its regulation by PAPC, C-cadherin can also be controlled via ectodomain shedding (i.e., enzymatic removal of its extracellular domain). When the C-cadherin ectodomain is overexpressed in Xenopus embryos, convergent extension defects result79. Interestingly, instead of regulating C-cadherin adhesion, the ectodomain promotes not only interaction of the C-cadherin cytoplasmic tail with aPKC, but also the phosphorylation of aPKC79. It will be interesting to determine in detail how how C-cadherin leads to aPKC phosphorylation and to assess the subcellular distribution of phospho-aPKC, given that aPKC itself is found mostly at the protrusive tips of cells63. In conclusion, decreased adhesion via PAPC and C-cadherin ectodomain shedding are required for chordamesodermal mediolateral intercalation. PAPC also regulates the cytoskeleton through Rho and JNK, and both functions for PAPC may partially depend on interactions with PCP signalling.

Matrix interactions during frog convergent extension

Mediolateral intercalation also depends on integrin α5β1-mediated attachment to fibronectin fibrils, which assemble on the dorsal (ectodermal facing) surfaces of chordamesodermal cells80,81. A complex interplay exists between PCP signalling, C-cadherin, and fibronectin assembly within the chordamesoderm. A syndecan-4-dependent interaction of cells with fibronectin regulates PCP components in the chordamesoderm82,83. Conversely, Wnt11-dependent PCP signals regulate C-cadherin84. Syndecan-4 internalization may be regulated by its binding partner, Rspo3/spondin. Too much or too little Rspo3 leads to gastrulation defects, and loss of Rspo3 leads to protrusive abnormalities in chordamesodermal cells. Rspo3 regulates PCP signalling, probably via Wnt5a, Frizzled7, and downstream effectors85. In summary, these studies of the frog chordamesoderm show that for these non-epithelial cells, a complicated choreography exists that integrates tractive actomyosin-based protrusions, decreased cell adhesion, and extracellular matrix (ECM) cues, each interacting with PCP signalling to drive tissue convergence and extension.

Matrix interactions during notochord morphogenesis

Vertebrate chordamesodermal cells provide an important example of non-epithelial mediolateral intercalation. In some ways, however, such cells are a nascent tissue, without the constraints of a fully formed ECM and the marks of full tissue differentiation. Insights into mediolateral intercalation in a more differentiated, non-epithelial tissue have been gained from studies of the notochord, a defining feature of chordates. Although the notochord is formed from distinct cell types in different species (epithelial cells in ascidians 51,86 and deep mesodermal cells in vertebrates such as Xenopus and zebrafish87,88), in all cases it subsequently assumes a characteristic rod-shaped morphology (akin to a stack of coins). In both Xenopus87 and ascidians89, the protrusive activity of intercalating cells ceases as they reach the external boundary of the notochord; their outer edges flatten and spread as they contact this surface, suggesting that the cells undergo ‘boundary capture’. This boundary may be initially formed by actomyosin-mediated inhibition of C-cadherin clustering—and thus adhesion—between the notochord and the adjacent presomitic mesoderm downstream of Eph-ephrin signalling90. The notochord then stiffens via formation of intracellular vacuoles, which seem to lend the notochord its characteristic rigidity91. A specialized extracellular matrix (the basement membrane) is important for boundary capture and subsequent notochord morphogenesis88. Fibrillin deposition at the boundary between the presumptive notochord and somitic mesoderm in Xenopus correlates with dampened protrusive activity in intercalating cells, and this deposition is important for axial elongation and notochord morphogenesis92. Laminin is also deposited in the ECM at the notochord surface. In ascidians, the chonmague/laminin α mutation leads to initially normal intercalation, but subsequent loss of polarization and tissue segregation in the notochord54,89. Similarly, mutations in zebrafish laminin subunits lead to pronounced defects in notochord morphogenesis93, and it is possible that this could also reflect defects in boundary capture; motility analysis will be required to test this. Integrins presumably mediate the interaction with the ECM at the boundary; in zebrafish, phosphorylated focal adhesion kinase (FAK) accumulates in rings at sites of notochord-ECM contact94.

PCP signalling is probably required for the completion of notochord morphogenesis, although it is difficult to distinguish defects arising at earlier stages (for example, during gastrulation) from those occurring at the time the notochord is formed. Indeed, PCP components are polarized during notochord intercalation. In ascidians53 and zebrafish95,96, Prickle is found at the anterior of intercalating cells, and in zebrafish, Dishevelled is found in the posterior96 (Figure 3c). In addition, in ascidians, laminin α and Prickle mutations synergize to yield a complete failure of intercalation; this suggests that although Prickle-dependent PCP signalling is more important early, both act together as intercalation proceeds89 (Figure 3a). In zebrafish, the PCP effector Daam1/formin undergoes dynamic changes in localization prior to and during notochord morphogenesis. Early in intercalation, Daam1 is found in vesicles in the cell cortex, but later it associates with actin fibres in elongating cells97. Daam1 binds to class B Eph receptors, leading to the suggestion that Daam1 is regulated by Eph-dependent internalization early, but then regulates PCP-dependent actin cables during notochord intercalation97. The adhesion G-protein-coupled receptor Gpr125 seems to act upstream of PCP in the developing zebrafish notochord, and perturbing its levels yields defects in the mediolateral intercalation of prechordal plate mesoderm in a manner that is consistent with PCP defects. Moreover, Gpr125 and Dishevelled can physically interact98. How Gpr125 activity integrates with the cues that appear to be provided by the ECM boundary that forms between presumptive notochord and somites is unclear. Nevertheless, the notochord represents a clear example in which tissue boundary formation, accompanied by ECM deposition, feeds into a tissue polarity pathway, which in turns orients mediolateral intercalation in a differentiated, non-epithelial tissue.

From the inside out: radial intercalation

Whereas mediolateral intercalation of epithelial and deep mesodermal cells changes the shape of tissues within a single plane, radial intercalation involves cells throughout the thickness of a tissue. Radial intercalation is a major driving force for tissue thinning and concomitant tissue spreading, or epiboly, during gastrulation. Such movements were first extensively characterized in the animal cap ectoderm of the Xenopus embryo99. In this context, late phases of animal cap spreading require cell-matrix interactions between integrin and fibronectin82. Here, we focus on recent insights gained from studies of radial intercalation during mesoderm formation in Drosophila, epiboly in the zebrafish gastrula, prechordal plate mesoderm formation in Xenopus, and within the Xenopus epidermis late in embryogenesis (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Radial intercalation drives morphogenesis during gastrulation and later in development.

a, Radial intercalation of the Drosophila mesoderm (red) requires long-range FGF signals from the ectoderm to polarize radial protrusions. These radial protrusions extend into the mesoderm, where they promote E-cadherin-mediated adhesions between mesodermal cells. There is still some question about the involvement of integrin, which is expressed by mesodermal cells, in this process. b, Zebrafish epiboly depends on radial intercalation of deep cells (green) underneath the enveloping layer (EVL). Cell adhesion mediated by EpCAM in the EVL and E-cadherin in the deep cells and/or the EVL are required for intercalation. E-cadherin is regulated by the G protein Gα12/13. Strong E-cadherin attachment to the cytoskeleton, via α-catenin inhibits blebbing, allowing for efficient radial intercalation. The EGF pathway, which is downstream of the transcription factor Pou5f1, is required for proper E-cadherin endocytosis and normal intercalation. E-cadherin-mediated adhesion counterbalances α-catenin/Ezrin-mediated blebbing in deep cells. c, Radial intercalation in the Xenopus prechordal plate mesoderm also relies on long range signals. PDGF-A, secreted from the overlying blastocoel roof is required for radial orientation of cell protrusions and radial intercalation. Intercalation fails when PDGF-A is depleted by morpholinos (MO). d, Radial intercalation of ciliated cell precursors (CCPs) into the outer superficial layer in Xenopus skin depends both cell-autonomously on factors to specify the apical edge (including Rab11 recycling) and cell-non-autonomously on factors that bind to the extracellular matrix (including dystroglycan, which increases levels of E-cadherin, fibronectin and laminin). After CCP radial intercalation, it matures into a ciliated cell.

FGF signalling in the Drosophila mesoderm

After the presumptive mesoderm in Drosophila is internalized, it spreads dorsally by radial intercalation and forms a monolayer under the ectoderm as GBE proceeds 100–102. Although E-cadherin is transcriptionally inhibited in mesoderm cells via snail, these cells retain maternal E-cadherin and E-cadherin mutants have defects in mesodermal development102. Maternal E-cadherin accumulates in protrusions that extend between the basolateral edges of the mesodermal and ectodermal cells at later stages of GBE (Figure 4A, inset). This indicates that radial intercalation might depend on E-cadherin-mediated adhesion between the two cell layers.

In addition to the importance of cell-cell adhesion, cell-cell signalling is crucial during radial intercalation in the Drosophila mesoderm. Actin-rich, radially directed protrusions101,102 seem to be required for intercalation itself, as mutations in the FGF ligands thisbe and pyramus, which are secreted from the ectoderm101, or in the FGF receptor heartless, localized in the mesoderm100, result in embryos that have fewer intercalation events along with fewer protrusions (Figure 4A). These protrusions, which contact the overlying ectoderm, seem to require Rap1101 and Cdc42102. There are contrasting reports regarding an additional requirement for β-integrin101,102. Therefore, the fly mesoderm depends on long-range FGF signals to direct protrusions that adhere to the overlying ectoderm via E-cadherin.

Radial intercalation during zebrafish gastrulation

Radial intercalation of deep cells within the zebrafish embryo is thought to partially drive the process of epiboly103 (Figure 4B), during which the embryo thins and envelops the underlying yolk over the course of several hours. Mutants that disrupt epiboly have been known for some time104,105 and were eventually shown to result from mutation of half-baked/E-cadherin103. Interestingly, deep cells in these mutants still transiently intercalate radially to the exterior deep cell layer, but they eventually move back towards their original location (so called ‘reverse intercalation’)103. Until recently, it was thought that a gradient of E-cadherin biased deep cell migrations from the internal cell layers to external ones103. But this gradient has been called into question106, and careful, computationally assisted time-lapse recordings have shown that there is no inward/outward directional bias of deep cell migration107. Together, this suggests that cadherin is required for radially intercalated cells to properly integrate into their new location, resulting in successful tissue epiboly. There is still some question regarding whether E-cadherin function is required for deep cell intercalation only within the deep cell population itself103 or also in the overlying enveloping layer108,109, as is the case for another cell adhesion molecule, EpCAM109. Consistent with this role of E-cadherin, the same deep cell phenotype was recently described for knockdown of zebrafish α-catenin110. Interestingly, however, the α-catenin knockdown does not absolutely phenocopy the E-cadherin mutant. Loss of α-catenin — or the ERM protein ezrin that attaches the cell cortex to the cell membrane — results in ectopic, myosin-dependent blebbing of deep cells110. Interestingly, these blebs can be stabilized by simultaneously knocking down E-cadherin, suggesting that α-catenin/ERM-mediated blebbing is counterbalanced by strong E-cadherin-mediated adhesion during successful epiboly.

Other perturbations have also been found to phenocopy the E-cadherin intercalation phenotype. The EGF pathway, downstream of the Pou5f1transcription factor, is required for proper E-cadherin endocytosis106. E-cadherin trafficking seems to be critical for forming new adhesions during radial intercalation, as loss of this pathway prevents successful tissue epiboly106,111. Overexpression or knockdown of the heterotrimeric G protein, Gα12/13, results in defects in deep cell epiboly112. Gα12/13 may act during epiboly via a direct physical association with the cytoplasmic tail of E-cadherin, occluding its β-catenin binding site112 and thereby the attachment of E-cadherin to the actin cytoskeleton via α-catenin. Thus, it seems that tight regulation of E-cadherin function, either through endocytosis or protein-protein interactions, is required for deep cell radial intercalation during zebrafish epiboly.

PDGF drives intercalation of Xenopus prechordal plate mesoderm

During Xenopus gastrulation, radial intercalation also occurs in the chordamesoderm113 (in addition to extensive mediolateral intercalation, Figure 3A) and the adjacent prechordal plate mesoderm (PCM). Whereas radial intercalation in the chordamesoderm does not require overlying the blastocoel roof113, radial intercalation in the prechordal plate mesoderm requires PDGF, produced by the blastocoel roof114. Intercalating PCM cells extend protrusions towards the blastocoel roof, and the orientation of these protrusions are disrupted when expression of the short isoform of PDGF-A is abrogated in Xenopus (Figure 4C). Radial intercalation fails in these embryos, suggesting that PDGF-dependent protrusive activity is required for intercalation114. Thus, similarly to the fly mesoderm, long-range signals direct protrusive activity and radial intercalation in the frog PCM.

Radial intercalation of Xenopus epidermal cells

Radial intercalation can also occur after gastrulation. Normal development of the skin in Xenopus requires radial intercalation of multiple cell types115,116, including ciliated cell precursors (CCPs), from the inner sensorial layer to the outer superficial layer (Figure 4D). Although a detailed analysis of adhesion function in this process is lacking, E-cadherin is present in both layers of the developing skin117. Moreover, CCPs intercalate into the superficial layer specifically at vertices of at least three cells, indicating that junction adhesion may be important here115. The vertices of rosettes during epithelial mediolateral intercalation represent regions of minimal adhesion due to junction collapse from myosin-mediated constriction and endocytosis. Thus it is possible that CCPs may be able to break through into the external layer at these sites. Similarly to the Drosophila tracheal system, the GTPase Rab11 is required for correct intercalation of epidermal cells. What role Rab11 plays is less clear, however, as Rab11 is required for correct apicobasal polarization of cells throughout the epidermis118. In Drosophila tracheal cells, E-cadherin is a major cargo carried by Rab11-positive vesicles24. But, so far, it is unclear which molecules are moved in Rab11-positive vesicles during skin development. Nonetheless, it seems that apicobasal polarity is either required for, or established by, intercalation into the outer superficial layer.

The laminin-binding transmembrane receptor dystroglycan seems to have a non-autonomous role in skin radial intercalation117. In the skin, dystroglycan is expressed in the more internal, sensorial layer (Figure 4D, 5). Interestingly, however, although it is not expressed in the CCPs, dystroglycan is required for their radial intercalation117. In dystroglycan-depleted embryos, laminin accumulation is lost, and both fibronectin and E-cadherin are downregulated117. This suggests that control of CCP radial intercalation is partially non-autonomous and depends on cell-cell and cell-extracellular matrix adhesion117. Unlike the animal cap in vertebrate gastrulae, CCP radial intercalation is a promising system for understanding how cells can engage in radial intercalation in a substantially differentiated epithelium. The molecules that have already been identified in this system suggest that in addition to molecular conservation with other examples of radial intercalation, there will probably be additional unique requirements in this and similar systems.

In summary, the control of radial intercalation seems to be context-dependent. Early in development, long-range signals control protrusive activity (fly mesoderm and frog PCM) or cell adhesion (zebrafish epiboly) to promote radial intercalation. More differentiated, apicobasal polarized epithelia (for example, frog skin) are also capable of radial intercalation through a mechanism that is not fully understood but which involves Rab11 and ECM interactions.

Conclusions and perspective

Major advances in our understanding of cell intercalation at the molecular level have been amassed during the past 25 years. Despite the distinct mechanisms that have been identified in varying biological contexts, several common themes have emerged.

Two major programmes of mediolateral intercalation have been identified. One, observed in ectodermal sheets and various epithelial tubes, relies on actomyosin-mediated shrinking of junctions that are oriented perpendicular to the axis of extension. The second programme is perhaps best illustrated in the Xenopus chordamesoderm, where cells elongate and develop protrusions perpendicular to the axis of extension. In both cases, cells are highly oriented. In many cases, this requires the PCP pathway, which specifies either junction shrinking or protrusive activity. But there are some notable cases, such as C. elegans dorsal intercalation50 and Drosophila GBE10, where no or only some PCP components are required. It will be interesting to determine whether redundant mechanisms work alongside PCP signalling in these last examples, or whether other novel mechanisms control planar polarity in these contexts.

Both types of mediolateral intercalation programme tightly regulate cell adhesion. For example, polarized endocytosis and disassembly of vertical junctions operates in several contexts in which intercalation is driven by actomyosin-mediated shrinking of junctions, whereas local inhibition of cadherin by PAPC operates in examples of intercalation driven by cell protrusion and elongation. Whereas epithelial cells generally favour the former and mesodermal cells favour the latter, such strategies may represent the poles of a spectrum, rather than binary options (Figure 1B). Dorsal epidermal cells in the C. elegans embryo and the ascidian notochord primordium generate basolateral protrusions45,49,51 and may represent an alternative intercalation programme in the middle of this spectrum. It will be interesting to determine what advantages are afforded by specific mechanisms of mediolateral intercalation.

In contrast to mediolateral intercalation, the mechanisms governing radial intercalation are highly context-dependent, with fewer conserved features. Cell-cell adhesion seems to be required to maintain the final position of a cell, rather than for intercalation itself. In the majority of cases studied, radially intercalating cells—epithelial or mesenchymal—seem to extend protrusions in the direction of migration102,114,115. Thus, similarly to mediolateral intercalation, radial intercalation requires polarized modifications to the actomyosin network. However, whereas PCP signalling is a prominent feature of mediolateral intercalation, this may not be the case for radial intercalation. For example, PCP is not required for radial intercalation in Xenopus skin119. It is intriguing, then, to think that in lieu of PCP signalling, radially intercalating cells require other long-range signals for polarization of their protrusions and successful intercalation, including PDGF (in Xenopus prechordal plate mesoderm) and FGF (in the Drosophila mesoderm).

Another key question is how intercalation programmes differ from related events, such as collective migration, that seem to predominate in certain elongating tissues during development. Different organisms seem to utilize one or the other of these behaviours to differing extents. Zebrafish, for example, rely much more heavily on collective migration to extend the anterior-posterior axis during development55. To what extent these two behaviours are part of a large meta-programme of ‘social migration’ remains to be clarified.

Finally, insights into intercalation will provide new understanding of related processes, many of which have relevance to human disease. Studies of intercalation programmes in model systems have revealed important aspects of the etiology of neural tube defects in humans120–122, which may in part arise due to insufficient polarization of intercalating cells through the PCP pathway. An additional intriguing possibility is the bearing of intercalation programmes on diseases in post-embryonic tissues. For example, the protrusive activity of intercalating cells bears similarities to the invasive behaviour of metastatic cells derived from aggressive tumours; it is possible that some of the same regulatory cassettes (or portions thereof) that are tightly regulated during intercalation events are ectopically activated in cancer cells123. In other cases, activation of intercalation may alleviate the progression of disease, as in kidney cysts28,33. Clearly, deeper understanding of how intercalation programmes are activated will be needed to fully realise their potential in treating human patients. As future work clarifies the detailed mechanisms underlying examples of radial and mediolateral intercalation, an even deeper appreciation of these fundamental cellular behaviours will emerge.

Online Summary.

Cell-cell intercalation is a process that occurs throughout animal development in which neighbouring cells exchange places. Intercalation can occur within a single plane (for example, mediolateral), or between adjacent planes (radial) and has multiple roles during gastrulation and organogenesis.

The Drosophila germband and various epithelial tubes in vertebrates (for example, the kidney collecting duct, cochlea and neural tube) undergo epithelial mediolateral intercalation through the contraction and ultimate disassembly of apical junctions that are oriented perpendicular to the axis of tissue extension. When these junctions collapse, rosettes form, which resolve to lengthen the tissue along the axis of extension.

Mediolateral intercalation of epithelial cells in some systems involves highly polarized basolateral protrusions that may mediate rearrangement.

Mesodermal cells in Xenopus undergo mediolateral intercalation via tractive protrusions, and downregulate C-cadherin-mediated cell-cell adhesions as they do so.

Some extracellular matrices can act to restrict mesodermal intercalation along a boundary (e.g., in the chordate notochord), whereas others serve as a permissive requirement for mesodermal intercalation (e.g., fibronectin in amphibian deep cells).

Radial intercalation of either deep or epithelial cells depends on contextual cues for successful polarization, protrusion formation, and intercalation. Unlike mediolateral intercalation, radial intercalation is generally independent of the planar cell polarity pathway.

Acknowledgments

E.W.-S. was supported by a Genetics Training Grant (US National Institutes of Health (NIH) T32 GM007133). Work in the authors’ laboratory was supported by NSF grant IOB 0518081 and NIH grant R01 GM58038 (awarded to J.H).

Definitions

- morphogenesis

the process by which an embryo generates its shape, governed by massive cellular movements

- mediolateral intercalation

a specific means by which convergent extension can occur in embryos with bilateral symmetry; neighbouring cells within the same plane exchange places with one other along the mediolateral axis to elongate the tissue in the orthogonal axis

- radial intercalation

the process by which cells in adjacent layers throughout the thickness of a multilayered tissue exchange places with one another

- convergent extension

directional cell rearrangement that results in dramatic lengthening along one axis of a tissue at the expense of narrowing along an orthogonal axis

- gastrulation

the process by which the three primary germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, endoderm) are specified and properly positioned

- germband extension

a phase of early Drosophila morphogenesis, which involves mediolateral intercalation of epidermal cells via shortening of specific cell-cell junctions

- rosette

a transient, multicellular structure that forms as an intermediate during epithelial mediolateral intercalation through the collapse of specific cell-cell junctions

- cochlea

the long, coiled region of the inner ear required for auditory function

- neural tube closure

a morphogenetic process in vertebrates in which the neuroepithelium intercalates and then folds into a cylinder; failure of this process leads to common human birth defects

- chordamesoderm

axial mesoderm in amphibian embryos, which undergoes extensive convergent extension and eventually gives rise to the notochord; in Xenopus, this tissue is derived from the deep cells of the dorsal involuting marginal zone

- notochord

a mesodermal structure that lies below—and aids in the proper specification of—the neural tube; it persists in some chordates but degenerates in most vertebrates

- Keller explant

Can be microsurgically isolated from part of the Xenopus gastrula; explants containing the dorsal marginal zone can autonomously undergo convergent extension

- epiboly

the spreading of a tissue, at the expense of its radial thickness, to envelop underlying cells; typically driven by radial intercalation

- prechordal plate

a portion of the involuting marginal zone in Xenopus that ultimately forms the anterior notochord; the prechordal plate mesoderm (PCM) undergoes extensive radial intercalation and involutes before the adjacent chordamesoderm

- adherens junctions

a junction protein complex that mediates cell-cell adhesion; composed of the transmembrane cell adhesion molecule, cadherin, and catenins, which couple the complex to the actin cytoskeleton; in vertebrate embryos, there are multiple classes of cadherin: E-cadherin is found in epithelia and early mammalian embryos, whereas C-cadherin is found in the early frog embryo during gastrulation.

Biography

Biography

Jeff Hardin is in the Department of Zoology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. His group focuses on cellular and molecular mechanisms of epidermal morphogenesis in C. elegans embryos. Elise Walck-Shannon is in the Genetics Graduate Program at the University of Wisconsin. She studies dorsal intercalation in the C. elegans embryo.

Footnotes

Competing interests statement: The authors declare no competing interests.

Works Cited

- 1.Keller R. Developmental biology. Physical biology returns to morphogenesis. Science. 2012;338:201–3. doi: 10.1126/science.1230718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Keller R. Mechanisms of elongation in embryogenesis. Development. 2006;133:2291–2302. doi: 10.1242/dev.02406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wallingford JB. Planar cell polarity and the developmental control of cell behavior in vertebrate embryos. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2012;28:627–53. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-092910-154208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carroll TJ, Yu J. The kidney and planar cell polarity. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2012;101:185–212. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394592-1.00011-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tada M, Kai M. Planar cell polarity in coordinated and directed movements. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2012;101:77–110. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394592-1.00004-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gray RS, Roszko I, Solnica-Krezel L. Planar cell polarity: coordinating morphogenetic cell behaviors with embryonic polarity. Dev Cell. 2011;21:120–33. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.May-Simera H, Kelley MW. Planar cell polarity in the inner ear. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2012;101:111–40. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394592-1.00006-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harris TJC, Tepass U. Adherens junctions: from molecules to morphogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:502–14. doi: 10.1038/nrm2927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Irvine KD. Cell intercalation during Drosophila germband extension and its regulation by pair-rule segmentation genes. Development. 1994;120 doi: 10.1242/dev.120.4.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zallen JA, Wieschaus E. Patterned gene expression directs bipolar planar polarity in Drosophila. Dev Cell. 2004;6:343–55. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bertet C, Sulak L, Lecuit T. Myosin-dependent junction remodelling controls planar cell intercalation and axis elongation. Nature. 2004;429:667–71. doi: 10.1038/nature02590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blankenship JT, Backovic ST, Sanny JSP, Weitz O, Zallen JA. Multicellular rosette formation links planar cell polarity to tissue morphogenesis. Dev Cell. 2006;11:459–70. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rauzi M, Verant P, Lecuit T, Lenne PF. Nature and anisotropy of cortical forces orienting Drosophila tissue morphogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:1401–10. doi: 10.1038/ncb1798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fernandez-Gonzalez R, Simoes S, de M, Röper J-C, Eaton S, Zallen JA. Myosin II dynamics are regulated by tension in intercalating cells. Dev Cell. 2009;17:736–43. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rauzi M, Lenne PF, Lecuit T. Planar polarized actomyosin contractile flows control epithelial junction remodelling. Nature. 2010;468:1110–4. doi: 10.1038/nature09566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Da Silva SM, Vincent JP. Oriented cell divisions in the extending germband of Drosophila. Development. 2007;134:3049–54. doi: 10.1242/dev.004911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Butler LC, et al. Cell shape changes indicate a role for extrinsic tensile forces in Drosophila germ-band extension. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:859–64. doi: 10.1038/ncb1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sawyer JK, et al. A contractile actomyosin network linked to adherens junctions by Canoe/afadin helps drive convergent extension. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:2491–2508. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-05-0411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Simões S, de M, et al. Rho-kinase directs Bazooka/Par-3 planar polarity during Drosophila axis elongation. Dev Cell. 2010;19:377–88. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Levayer R, Pelissier-Monier A, Lecuit T. Spatial regulation of Dia and Myosin-II by RhoGEF2 controls initiation of E-cadherin endocytosis during epithelial morphogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2011;13:529–40. doi: 10.1038/ncb2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tamada M, Farrell DL, Zallen JA. Abl regulates planar polarized junctional dynamics through β-catenin tyrosine phosphorylation. Dev Cell. 2012;22:309–19. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.12.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Levayer R, Lecuit T. Oscillation and Polarity of E-Cadherin Asymmetries Control Actomyosin Flow Patterns during Morphogenesis. Dev Cell. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2013.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sawyer JK, et al. A contractile actomyosin network linked to adherens junctions by Canoe/afadin helps drive convergent extension. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:2491–508. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-05-0411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Warrington SJ, Strutt H, Strutt D. The Frizzled-dependent planar polarity pathway locally promotes E-cadherin turnover via recruitment of RhoGEF2. Development. 2013;140:1045–54. doi: 10.1242/dev.088724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nishimura T, Honda H, Takeichi M. Planar cell polarity links axes of spatial dynamics in neural-tube closure. Cell. 2012;149:1084–97. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.04.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nishimura T, Takeichi M. Shroom3-mediated recruitment of Rho kinases to the apical cell junctions regulates epithelial and neuroepithelial planar remodeling. Development. 2008;135:1493–502. doi: 10.1242/dev.019646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karner CM, et al. Wnt9b signaling regulates planar cell polarity and kidney tubule morphogenesis. Nat Genet. 2009;41:793–9. doi: 10.1038/ng.400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lienkamp SS, et al. Vertebrate kidney tubules elongate using a planar cell polarity-dependent, rosette-based mechanism of convergent extension. Nat Genet. 2012;44:1382–7. doi: 10.1038/ng.2452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang J, et al. Regulation of polarized extension and planar cell polarity in the cochlea by the vertebrate PCP pathway. Nat Genet. 2005;37:980–5. doi: 10.1038/ng1622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamamoto N, Okano T, Ma X, Adelstein RS, Kelley MW. Myosin II regulates extension, growth and patterning in the mammalian cochlear duct. Development. 2009;136:1977–86. doi: 10.1242/dev.030718. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chacon-Heszele MF, Ren D, Reynolds AB, Chi F, Chen P. Regulation of cochlear convergent extension by the vertebrate planar cell polarity pathway is dependent on p120-catenin. Development. 2012;139:968–78. doi: 10.1242/dev.065326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ybot-Gonzalez P, et al. Convergent extension, planar-cell-polarity signalling and initiation of mouse neural tube closure. Development. 2007;134:789–99. doi: 10.1242/dev.000380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nishio S, et al. Loss of oriented cell division does not initiate cyst formation. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2010;21:295–302. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2009060603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neumann HPH, et al. Epidemiology of autosomal-dominant polycystic kidney disease: an in-depth clinical study for south-western Germany. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2013;28:1472–87. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfs551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McKenzie E, Krupin A, Kelley MW. Cellular growth and rearrangement during the development of the mammalian organ of Corti. Dev Dyn. 2004;229:802–12. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.10500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen P, Johnson JE, Zoghbi HY, Segil N. The role of Math1 in inner ear development: Uncoupling the establishment of the sensory primordium from hair cell fate determination. Development. 2002;129:2495–2505. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.10.2495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen CK, et al. The transcription factors KNIRPS and KNIRPS RELATED control cell migration and branch morphogenesis during Drosophila tracheal development. Development. 1998;125:4959–68. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.24.4959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ribeiro C, Neumann M, Affolter M. Genetic control of cell intercalation during tracheal morphogenesis in Drosophila. Curr Biol. 2004;14:2197–207. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.11.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Araújo SJ, Cela C, Llimargas M. Tramtrack regulates different morphogenetic events during Drosophila tracheal development. Development. 2007;134:3665–76. doi: 10.1242/dev.007328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shaye DD, Casanova J, Llimargas M. Modulation of intracellular trafficking regulates cell intercalation in the Drosophila trachea. Nat Cell Biol. 2008;10:964–70. doi: 10.1038/ncb1756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shindo M, et al. Dual function of Src in the maintenance of adherens junctions during tracheal epithelial morphogenesis. Development. 2008;135:1355–64. doi: 10.1242/dev.015982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Caussinus E, Colombelli J, Affolter M. Tip-cell migration controls stalk-cell intercalation during Drosophila tracheal tube elongation. Curr Biol. 2008;18:1727–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.10.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nishimura M, Inoue Y, Hayashi S. A wave of EGFR signaling determines cell alignment and intercalation in the Drosophila tracheal placode. Development. 2007;134:4273–82. doi: 10.1242/dev.010397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sulston JE, Schierenberg E, White JG, Thomson JN. The embryonic cell lineage of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol. 1983;100:64–119. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(83)90201-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Williams-Masson EM, Heid PJ, Lavin CA, Hardin J. The cellular mechanism of epithelial rearrangement during morphogenesis of the Caenorhabditis elegans dorsal hypodermis. Dev Biol. 1998;204:263–76. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1998.9048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Fridolfsson HN, Starr DA. Kinesin-1 and dynein at the nuclear envelope mediate the bidirectional migrations of nuclei. J Cell Biol. 2010;191:115–128. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201004118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Starr DA, et al. unc-83 encodes a novel component of the nuclear envelope and is essential for proper nuclear migration. Development. 2001;128:5039–50. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.24.5039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Heid PJ, et al. The zinc finger protein DIE-1 is required for late events during epithelial cell rearrangement in C. elegans. Dev Biol. 2001;236:165–80. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Patel FB, et al. The WAVE/SCAR complex promotes polarized cell movements and actin enrichment in epithelia during C. elegans embryogenesis. Dev Biol. 2008;324:297–309. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.09.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.King RS, et al. The N- or C-terminal domains of DSH-2 can activate the C. elegans Wnt/beta-catenin asymmetry pathway. Dev Biol. 2009;328:234–44. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.01.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Munro EM, Odell GM. Polarized basolateral cell motility underlies invagination and convergent extension of the ascidian notochord. Development. 2002;129:13–24. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.1.13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]