Abstract

Introduction

Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) repair has been performed by various surgical specialties for many years. Endovascular aneurysm repair (EVAR) may be a disruptive technology, impacting which specialties care for patients with AAA. Therefore, we examined the proportion of AAA repairs performed by various specialties over time in the United States and evaluated the impact of the introduction of EVAR.

Methods

The Nationwide Inpatient Sample, 2001-2009, was queried for intact and ruptured AAA and for open repair and EVAR. Specific procedures were used to identify vascular surgeons (VS), cardiac surgeons (CS), and general surgeons (GS) as well as interventional cardiologists (IC), and interventional radiologists (IR) for states that reported unique treating physician identifiers. Annual procedure volumes were subsequently calculated for each specialty.

Results

We identified 108,587 EVAR and 85,080 open AAA repairs (3,011 EVAR and 12,811 open repairs for ruptured AAA). VS performed an increasing proportion of AAA repairs over the study period (52% in 2001 to 66% in 2009, P < .001). GS and CS performed fewer repairs over the same period (25% to 17%, P < .001 and 19% to 13%, P < .001, respectively). EVAR was increasingly utilized for intact (33% to 78% of annual cases, P < .001) as well as ruptured AAA repair (5% to 28%, P < .001). The proportion of intact open repairs performed by VS increased from 52% to 65% (P < .001), while for EVAR the proportion went from 60% to 67% (P < .001). For ruptured open repairs, the proportion performed by VS increased from 37% to 53% (P < .001) and for ruptured EVAR repairs from 28% to 73% (P < .001). Compared to treatment by VS, treatment by a CS (0.55 [0.53-0.56]) and GS (0.66 [0.64-0.68]) was associated with a decreased likelihood of undergoing endovascular rather than open AAA repair.

Conclusions

VS are performing an increasing majority of AAA repairs, in large part driven by the increased utilization of EVAR for both intact and ruptured AAA repair. However, GS and CS still perform AAA repair. Further studies should examine the implications of these national trends on the outcome of AAA repair.

Introduction

During the late 20th century, surgery has become a technology driven profession.1 Since then, innovations such as endoscopic and endovascular surgery have transformed clinical medicine. Besides changing the procedure itself, these disruptive technologies have had their effect on the type of physicians performing the procedures. Percutaneous coronary intervention, for example, has diminished the proportion of coronary revascularizations performed by cardiac surgeons, while the proportion of interventional cardiologists increased dramatically with the use of this technique.2 For abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) repair, it is unclear how the introduction and widespread adoption of endovascular repair (EVAR) has changed the distribution of specialties performing elective and ruptured AAA repair.

Prior to the introduction of EVAR, open surgical repair was the primary method of treatment. Using Medicare data, Birkmeyer et al. showed that between 1998 and 1999, prior to the widespread adoption of EVAR, vascular surgeons (VS) performed 39% of all elective AAA repairs, while cardiac and general surgeons (CS, GS) performed 33% and 28%, respectively.3 In contrast to elective AAA repair, general surgeons performed the largest proportion of ruptured AAA repairs at 39%, followed by vascular surgeons at 33% and cardiac surgeons at 29%.4 Currently, as with coronary revascularization, the endovascular approach has also led to the inclusion of nonsurgical specialties in treating patients with AAA, such as interventional cardiology (IC) and interventional radiology (IR). Since the performance of EVAR requires a specific skill set that has not been mastered by many surgeons from other specialties, we hypothesize that the proportion of surgical specialties other than VS (i.e., GS and CS) has declined, while VS, IR, and IC are responsible for an increasing number of patients due to a shift from open repair towards EVAR.

The purpose of this study is to analyze how the introduction of EVAR has influenced which specialties are providing care for AAA patients for both elective and ruptured AAA repair in the United States.

Methods

Database

The Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) is the largest national administrative database and represents a 20% sample of all payer (insured and uninsured) hospitalizations. The NIS is maintained by the Agency for Health Care Research and Quality as part of the Healthcare Cost and Utilization Project. Years 2001 to 2009 were queried using International Classification of Diseases, 9th revision (ICD-9) codes to identify patients with diagnosis codes for intact (i.e. elective, symptomatic and mycotic aneurysms) AAA (441.4) and ruptured AAA (441.3). ICD-9 coding does not distinguish infrarenal from juxtarenal or suprarenal AAA. More recent years could not be interrogated due to discontinuation of the surgeon identification variables in the NIS database after 2009.5 Patients who underwent open AAA repair (38.44, 39.25) or EVAR (39.71) were selected. Patients with procedural codes for both open repair and EVAR were considered to have undergone EVAR, as they likely represent conversions to open repair. Patients with codes for a thoracic aneurysm (441.1 or 441.2), thoracoabdominal aneurysm (441.6 or 441.7) or aortic dissection (441.00-441.03) were excluded. As the NIS contains de-identified data only without protected health information, Institutional Review Board approval and patient consent were waived.

The primary outcome was proportional procedure volume by physician specialty over time for intact and ruptured AAA repair. We evaluated the uptake of EVAR overall and by specialty over time. Additionally, we assessed the likelihood of receiving EVAR rather than open repair by specialty.

Physician specialty

For AAA repair, we were interested in the following type physicians: vascular surgeons (VS), general surgeons (GS), cardiac surgeons (CS), interventional cardiologists (IC), and interventional radiologists (IR). The NIS provides unique physician identifiers per state that allow tracking of procedures performed by that physician during that specific year in that state. Of the available states, 27 provide 2 unique physician identifiers, with 22 of the 27 specifically detailing which physician performed the primary procedure (Supplemental Table I). For the remaining 5 states, the identifiers were only used when both identifiers were the same to ensure that the identified physician was the one performing the primary procedure. We composed a list of specific procedures (Supplemental Table II) that we used to determine the specialty of each physician (VS, GS, CS, IC, or IR). The top 15 procedures identified for each of the physician specialties are listed in Supplemental Table III. Similar approaches have been previously reported.6-8 Subsequently, a hierarchical model was created: each physician that performed >10 cardiac surgery procedures was labeled a CS; the remaining physicians that performed >10 interventional cardiology procedures (e.g. coronary stenting) were labeled IC; physicians with >10 interventional radiology procedures not typically performed by VS (e.g. liver biopsy, nephrostomy, etc.) were identified as IR; the remaining physicians whose procedures consisted of 75%-100% of vascular procedures with >10 in number, were classified as VS; physicians whose procedures consisted of 0-75% of vascular procedures and performed >10 general surgery procedures were classified as GS.. Similar approaches have been previously described.9, 10 Two hundred and ten procedures labeled as open repairs were coded as being performed by IC or IR (0.1% of total procedures). We felt these were most likely miscoded endovascular procedures and excluded these patients from further analyses.

Statistical approach

Mean and standard deviation are reported for parametric data. Baseline variables were compared using Chi-square tests or t-tests, where appropriate. We examined the proportional volume of open AAA repairs and EVAR for each specialty and how this changed over the study period. Trends over time were assessed using the Cochran-Armitage test for trend. A P-value less than .05 indicates that annual procedural volumes followed a significant upward or downward (i.e., non-random) trend over time. Multivariable logistic regression analysis was conducted to examine the influence of physician specialty type on the type of procedure performed, whether open or endovascular. Analyses were considered statistically significant when P < .05. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS 9.2 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and SPSS Statistics 21 (IBM Inc., Chicago, IL).

Results

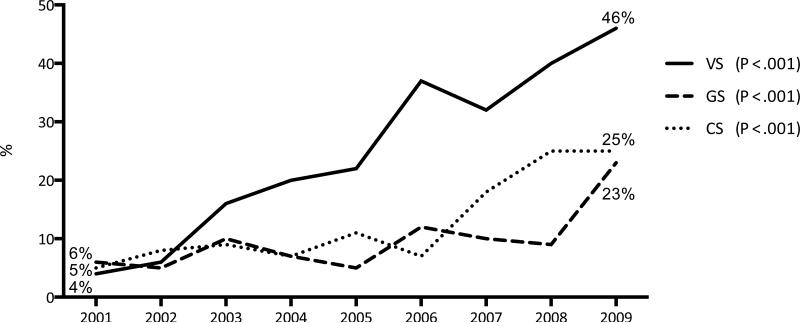

Overall, 108,587 EVAR and 85,080 open AAA repairs were identified in the study period, of which 3,011 EVAR and 12,811 open repairs were for ruptured AAA. The annual overall volume increased from 20,134 in 2001 to 22,541 in 2009 (P < .001). Patient and hospital characteristics are detailed in Table I. Of all AAA repairs, 61% of AAA repairs were performed by VS, 20% by GS and 16% by CS, while the remainder was performed by IC and IR (3% combined). Figure 1 illustrates changes over time for each physician specialty. VS performed an increasing proportion of AAA repairs over the study period (52% in 2001 to 66% in 2009, P < .001, Supplemental Table IV). During the same period, GS and CS performed fewer repairs (25% to 17%, P < .001 and 19% to 13%, P < .001, respectively). Similarly, the absolute number of VS performing AAA repair increased with 30% over the study period, while the number of GS and CS decreased over time (46% and 30%, respectively).

Table I.

Demographic and comorbidity characteristics of patients undergoing open aortic aneurysm repair or endovascular aneurysm repair per physician specialty.

| Open Repair | Endovascular Repair | Open EVAR | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| VS | GS | CS | P-value | VS | GS | CS | IC | IR | P-value | Overall | P-value | ||

| Number | 45,804 | 21,625 | 17,651 | 72,489 | 17,500 | 14,033 | 3,055 | 1,510 | 85,080 | 108,587 | |||

| Age (years) | 71.3 | 71.9 | 71 | < .001 | 73.7 | 74.0 | 72.8 | 73.1 | 74.1 | < .001 | 71.4 | 73.6 | < .001 |

| Female | 25.5% | 23.6% | 23.0% | < .001 | 18.3% | 16.9% | 15.4% | 16.8% | 17.0% | < .001 | 24.5% | 17.7% | < .001 |

| White race | 90.4% | 90.7% | 91.0% | .051 | 91.5% | 91.2% | 92.2% | 87.3% | 78.7% | < .001 | 90.6% | 91.2% | < .001 |

| Teaching hospital | 60.5% | 30.7% | 45.1% | < .001 | 63.9% | 33.8% | 48.4% | 46.3% | 41.0% | < .001 | 49.7% | 56.2% | < .001 |

| Urban location | 95.5% | 88.2% | 93.6% | < .001 | 95.4% | 92.8% | 93.9% | 100% | 97.2% | < .001 | 93.2% | 95.0% | < .001 |

| Hospital Bedsize | < .001 | < .001 | < .001 | ||||||||||

| Small | 7.0% | 8.2% | 5.5% | 8.6% | 4.4% | 8.2% | 13.0% | 0.0% | 7.0% | 7.9% | |||

| Medium | 17.9% | 26.7% | 23.0% | 15.5% | 22.1% | 19.5% | 9.4% | 24.4% | 21.2% | 17.0% | |||

| Large | 75.1% | 65.1% | 71.5% | 75.9% | 73.5% | 72.3% | 77.6% | 75.6% | 71.8% | 75.1% | |||

| Emergent admission | 13.6% | 21.0% | 11.5% | <0.001 | 3.0% | 2.6% | 2.0% | 1.4% | 3.0% | < .001 | 15.1% | 2.8% | < .001 |

EVAR, endovascular aneurysm repair; VS, vascular surgeons; GS, general surgeons; CS, cardiac surgeons; IC, interventional cardiologists; IR, interventional radiologists; P-values compare differences within the treatment groups

Figure 1.

Proportion of all abdominal aortic aneurysm repairs (both open and endovascular) performed by each physician specialty from 2001-2009 in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (totals sum to 100%)

Intact AAA Repair

With 55%, VS performed the majority of open AAA repairs (increasing from 52% to 65% from 2001 to 2009, P < .001). Over this same time period GS performed 24% of all intact open repairs (decreasing from 25% to 16%, P < .001), followed by CS with 22% of cases (24% to 19%, P <. 001, Figure 2A). VS also performed the majority of EVARs at 67%, (increasing from 60% to 67% from 2001 to 2009), followed by 16% performed by GS (19% to 17%, P < .001), 13% by CS (10.5% to 11.3%, P = .009) and 4% by IC and IR combined (10% to 6%, P = .015, Figure 2B). The absolute number of EVARs increased from 5,906 in 2001 (33% of the annual intact AAA repairs) to 16,252 in 2009 (78%). Over the same period, the number of open repairs decreased from 12,188 (67%) to 4,678 (22%). Consequently, EVAR has become the primary treatment method for intact AAA in all three surgical specialties (Figure 3). Since VS perform a greater proportion of endovascular procedures, the rise in EVAR utilization has in part led to VS performing an increasing majority of overall intact AAA repairs (54% in 2001 to 66% in 2009, P < .001).

Figure 2A.

Proportion of all open repairs for intact abdominal aortic aneurysms performed by physician specialty from 2001-2009 in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (totals sum to 100%)

Figure 2B.

Proportion of all endovascular repairs for intact abdominal aortic aneurysms performed by physician specialty from 2001-2009 in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (totals sum to 100%)

Figure 3.

Proportion of intact abdominal aortic aneurysms treated by endovascular repair within each specialty from 2001-2009 in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample

Rupture AAA Repair

VS performed 49% of open ruptured AAA repairs (increasing from 37% to 53%, P < .001, Figure 4A), followed by GS with 35% (44% to 33%, P < .001) and 16% by CS (19% to 14%, P = .001). With 73%, VS also carried out the majority of ruptured EVAR (rEVAR) (28% to 73%, P < .001, Figure 4B), while GS performed 15% (54% to 16%, P < .001) and CS 9% (18% to 8%, P = .008). IC and IR together are responsible for 3% of rEVARs (0% to 3%, P = .095). A dramatic overall increase in the utilization of rEVAR was observed (5% to 38% of the annual ruptured volume). This was most pronounced for VS, where the utilization of rEVAR went from 4% in 2001 to 46% in 2009 (P < .001, Figure 5).

Figure 4A.

Proportion of all open ruptured AAA repairs performed by physician specialty from 2001-2009 in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (totals sum to 100%)

Figure 4B.

Proportion of all EVARs for ruptured AAA repairs performed by physician specialty from 2001-2009 in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (totals sum to 100%)

Figure 5.

Proportion of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysms treated by endovascular repair within each specialty from 2001-2009 in the Nationwide Inpatient Sample

Likelihood of receiving EVAR

Compared to treatment by VS, treatment by CS and GS was associated with a significantly lower likelihood of receiving EVAR (OR: 0.55, 95% CI: 0.53 – 0.56 for CS and OR: 0.66, 95% CI: 0.64 – 0.68 for GS, Table II). Additionally, women (OR: 0.57, 95% CI: 0.55 – 0.58) those with non-white race (OR: 0.88 95% CI: 0.84 – 0.91), and emergency admission (OR: 0.14, 95% CI: 0.14 – 0.15) were significantly less likely to undergo EVAR. Advanced age (OR: 1.42, 95% CI: 1.40 – 1.44, per 10 years), treatment in a teaching hospital (OR: 1.27, 95% CI: 1.25 – 1.30) and urban designation of the hospital (OR: 1.33, 95% CI: 1.27 – 1.40) were predictive of EVAR. Over the study period, the probability for receiving EVAR increased annually (OR: 1.33, 95% CI: 1.32 – 1.34, per year).

Table II.

Multivariable predictors for the likelihood of receiving EVAR (OR >1 predicts EVAR)

| Variable | Odds ratio | 95% CI | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surgeon Specialty | |||

| Vascular surgeons | Reference | - | - |

| Cardiac surgeons | 0.55 | 0.53 – 0.56 | <.001 |

| General surgeons | 0.66 | 0.64 – 0.68 | <.001 |

| Emergent admission | 0.14 | 0.14 – 0.15 | <.001 |

| Age (per 10 y) | 1.42 | 1.40 – 1.44 | <.001 |

| Female sex | 0.57 | 0.55 – 0.58 | <.001 |

| Non-white race | 0.88 | 0.84 – 0.91 | <.001 |

| Year of surgery (per y) | 1.33 | 1.32 – 1.34 | <.001 |

| Teaching hospital | 1.27 | 1.25 – 1.30 | <.001 |

| Hospital location | 1.33 | 1.27 – 1.40 | <.001 |

| Hospital Bed size | |||

| Small | Reference | - | - |

| Medium | 0.72 | 0.69 – 0.76 | <.001 |

| Large | 0.98 | 0.94 – 1.02 | <.319 |

Discussion

The main finding of this study is that with the introduction of EVAR, the proportion of AAA repairs being performed by each physician specialty has changed. Vascular surgeons performed an increasing majority of both open and endovascular intact AAA repairs, while the proportion carried out by CS and GS has steadily declined. The distribution of specialties performing rAAA repair shifted from predominantly GS in the first years of the study towards VS in later years. Over the study period, EVAR has become the dominant treatment for intact AAA repair and is being utilized for an increasing number of ruptured AAA repairs as well. As EVAR is most likely performed by VS, the overall proportion of repairs done by VS –intact and ruptured– increased substantially with the widespread adoption of EVAR.

Regarding intact AAA repair, our results are in line with a study by Birkmeyer et al., showing that between 1998 and 1999 intact open repairs were predominantly performed by VS. However, Birkmeyer et al. found a relatively even distribution with 39% being done by VS, 33% by CS and 28% by GS, while our results showed that VS already performed a majority of the open repairs in the early years of the study and this difference continued to increase over time. Regionalization of open AAA repairs to high-volume centers during the turn of the century is likely to have contributed to VS being increasingly responsible for AAA surgery.11 In addition, retirement of senior surgeons who were trained at a time when GS and CS customarily performed repair of abdominal aortic aneurysms and may have been less likely to obtain endovascular skills may have added to the shift towards VS. Similar to the early years of our study, previous reports show that GS performed the majority of ruptured AAA repairs at 39%, followed by VS at 33%, and CS at 29% before the introduction of EVAR.12 As EVAR became more widely used in the emergency setting, this distribution changed towards a growing proportion of emergency repairs being performed by VS. Since VS also performed an increasing proportion of open rAAA repairs separately from trends in endovascular repair, centralization of rAAA care is likely to have contributed to the shift from GS towards VS as well. Yet a persistent presence of GS treating open rAAA repair remained, which could be due to geographic location where the presence of VS may be lacking.13 In these areas, the emergent nature of a ruptured AAA may preclude the transfer of the patient to a center with VS necessitating immediate treatment by an available GS.

The phenomenon of disruptive technologies in healthcare is not new. In coronary artery disease, the number of coronary revascularizations performed with coronary stenting rapidly increased after the first coronary stent was introduced in 1994, while the utilization of coronary bypass grafting declined.2 As a result, interventional cardiologists rather than cardiac surgeons currently perform the majority of coronary revascularizations. A similar shift was seen in vascular surgery with the introduction of carotid stenting. Before its introduction, carotid revascularization through endarterectomy was predominantly done by VS and, to a lesser extent GS, CS and neurosurgeons.14 We noted that GS and CS practice included a substantial percentage of carotid endarterectomies (8.6% and 10.0% of the selected procedures we identified, respectively) (Supplemental Table III). However, we did not evaluate changes in carotid revascularization over time in this study. After FDA approval in 2004, carotid stenting is increasingly utilized with rapid adoption by not only surgeons, but also interventional radiologists and interventional cardiologists.15, 16 Currently, carotid endarterectomy use is still declining, while some patients are being treated through stenting predominantly by interventional cardiologists.17, 18 EVAR has certainly changed how AAA is being treated but contrary to the examples above, VS have only increased their role as the treating surgeon for intact and ruptured AAA.

Our study has several limitations that should be addressed. Since administrative databases were used, important clinical data such as anatomical information or hemodynamic status, which could influence the choice of procedure and subsequent outcomes, could not be assessed. Additionally, the difficulty of distinguishing a pre-existing comorbid condition from a postoperative complication in this dataset makes an adequate risk-adjustment model difficult. Therefore, we chose not to perform outcomes analysis using NIS. However, the NIS does afford national representation of all age groups thus making it an optimal source of epidemiologic data. Also, as the NIS database does not include the specialty of the attending physician, we employed an algorithm incorporating specialty specific procedures similar to what has been described before.7, 19, 20 Our algorithm for identifying vascular surgeons is arbitrary (75% vascular surgery cases), suggesting that some board certified VS may have been mistakenly classified as GS or vice versa. However, our methodology reflects what physicians were actually doing routinely in practice and focused on the change over time. Additionally, our algorithm generated similar distributions of physician's specialty performing open repair in the early years of the current studied period when compared to a previously published large study using physician self identification of specialty.4 Further, procedures coded as open repairs performed by IC or IR (0.1%) were excluded from this study, as they are, most likely, miscoded endovascular procedures. Unfortunately, it is not possible to identify similar procedural coding errors for the remaining open repairs. Consequently, a very small proportion of miscoded procedures may have remained. Finally, the discontinuation of the surgeon-identifying variable after 2009 prevented the inclusion of more recent years. However, as is demonstrated in this study, the major shift from open repair to EVAR was already well established by 2009.21

Conclusions

Our results show that VS are performing an increasing majority of AAA repairs, in large part driven by the increased utilization of EVAR for both intact and ruptured AAA repair. However, GS and CS still perform AAA repair. Treatment by GS and CS, as well as emergent admission, female sex and non-white race are associated with a decreased likelihood of receiving EVAR. Advanced age, more recent year of surgery, treatment in a teaching hospital and urban designated area of the hospital increased the probability of receiving EVAR. Further studies should examine the implications of these national trends on the outcome of AAA repair.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Supported by grant 5R01HL105453-03 from the NHLBI and the NIH T32 Harvard-Longwood Research Training in Vascular Surgery grant HL007734.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.Riskin DJ, Longaker MT, Gertner M, Krummel TM. Innovation in surgery: a historical perspective. Ann Surg. 2006;244(5):686–93. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000242706.91771.ce. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Epstein AJ, Polsky D, Yang F, Yang L, Groeneveld PW. Coronary revascularization trends in the United States, 2001-2008. JAMA. 2011;305(17):1769–76. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Birkmeyer JD, Stukel TA, Siewers AE, Goodney PP, Wennberg DE, Lucas FL. Surgeon volume and operative mortality in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2003;349(22):2117–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa035205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cronenwett JLBJ, editor. The Dartmouth atlas of vascular health care. AHA Press; Chicago: 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Availability of Data Elements in the 1988-2012 National Inpatient Sample (NIS) [press release] NIS Database Documentation: HCUP2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Csikesz NG, Simons JP, Tseng JF, Shah SA. Surgical specialization and operative mortality in hepato-pancreatico-biliary (HPB) surgery. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12(9):1534–9. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0566-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Schipper PH, Diggs BS, Ungerleider RM, Welke KF. The influence of surgeon specialty on outcomes in general thoracic surgery: a national sample 1996 to 2005. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;88(5):1566–72. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.08.055. discussion 72-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vogel TR, Dombrovskiy VY, Carson JL, Haser PB, Graham AM. Lower extremity angioplasty: impact of practitioner specialty and volume on practice patterns and healthcare resource utilization. J Vasc Surg. 2009;50(6):1320–4. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.07.112. discussion 4-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dimick JB, Cowan JA, Jr., Stanley JC, Henke PK, Pronovost PJ, Upchurch GR., Jr. Surgeon specialty and provider volumes are related to outcome of intact abdominal aortic aneurysm repair in the United States. J Vasc Surg. 2003;38(4):739–44. doi: 10.1016/s0741-5214(03)00470-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liang P, Hurks R, Bensley RP, Hamdan A, Wyers M, Chaikof E, et al. The rise and fall of renal artery angioplasty and stenting in the United States, 1988-2009. J Vasc Surg. 2013;58(5):1331–8. e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2013.04.041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hill JS, McPhee JT, Messina LM, Ciocca RG, Eslami MH. Regionalization of abdominal aortic aneurysm repair: evidence of a shift to high-volume centers in the endovascular era. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48(1):29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.02.048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cronenwett JL, Birkmeyer JD. The Dartmouth Atlas of Vascular Health Care. Cardiovasc Surg. 2000;8(6):409–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maybury RS, Chang DC, Freischlag JA. Rural hospitals face a higher burden of ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm and are more likely to transfer patients for emergent repair. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;212(6):1061–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.02.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hollenbeak CS, Bowman AR, Harbaugh RE, Casale PN, Han D. The impact of surgical specialty on outcomes for carotid endarterectomy. J Surg Res. 2010;159(1):595–602. doi: 10.1016/j.jss.2008.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenfield K, Babb JD, Cates CU, Cowley MJ, Feldman T, Gallagher A, et al. Clinical competence statement on carotid stenting: training and credentialing for carotid stenting--multispecialty consensus recommendations: a report of the SCAI/SVMB/SVS Writing Committee to develop a clinical competence statement on carotid interventions. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45(1):165–74. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2004.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gray WA. A cardiologist in the carotids. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(9):1602–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.11.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nallamothu BK, Lu M, Rogers MA, Gurm HS, Birkmeyer JD. Physician specialty and carotid stenting among elderly medicare beneficiaries in the United States. Arch Intern Med. 2011;171(20):1804–10. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2011.354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skerritt MR, Block RC, Pearson TA, Young KC. Carotid endarterectomy and carotid artery stenting utilization trends over time. BMC Neurol. 2012;12:17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2377-12-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eppsteiner RW, Csikesz NG, Simons JP, Tseng JF, Shah SA. High volume and outcome after liver resection: surgeon or center? J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12(10):1709–16. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0627-3. discussion 16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Eslami MH, Csikesz N, Schanzer A, Messina LM. Peripheral arterial interventions: trends in market share and outcomes by specialty, 1998-2005. J Vasc Surg. 2009;50(5):1071–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2009.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dua A, Kuy S, Lee CJ, Upchurch GR, Jr., Desai SS. Epidemiology of aortic aneurysm repair in the United States from 2000 to 2010. J Vasc Surg. 2014;59(6):1512–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2014.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.