Abstract

Background and Purpose

Inflammatory injury plays a critical role in intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH)-induced secondary brain injury. Recently, Dopamine D2 receptor (DRD2) is identified an important component controlling innate immunity and inflammatory response in central nervous system and αB-crystallin (CRYAB) is a potent negative regulator on inflammatory pathways. Here, we sought to investigate the role of DRD2 on neuroinflammation after experimental ICH, and the potential mechanism mediated by CRYAB.

Methods

Two hundred and twenty-four (224) male CD-1 mice were subjected to intrastriatal infusion of bacterial collagenase or autologous blood. Two DRD2 agonists Quinpirole and Ropinirole were administrated by daily intraperitoneal injection starting at 1 hour post-ICH. DRD2 and CRYAB in vivo knockdown was performed 48 hour before ICH insult. Behavioral deficits and brain water content, western blots, immunofluorescence staining, co-immunoprecipitation assay and proteome cytokine array were evaluated.

Results

Endogenous DRD2 and CRYAB expression were increased after ICH. DRD2 knockdown aggravated the neurobehavioral deficits and the pronounced cytokines expression. DRD2 activation by Quinpirole and Ropinirole ameliorated neurological outcome, brain edema, IL-1β and MCP-1 expression, as well as microglia/macrophages activation in the perihematomal region. These effects were abolished by pretreated with CRYAB siRNAs. Quinpirole enhanced cytoplasmic binding activity between CRYAB and NF-κB, and decreased nuclear NF-κB expression. Similar therapeutic benefits were observed using autologous blood injection model and intranasal delivery of Quinpirole.

Conclusions

DRD2 may have anti-inflammatory effects after ICH. DRD2 agonists inhibited neuroinflammation and attenuated brain injury after ICH, which is probably mediated by CRYAB and enhanced cytoplasmic binding activity with NF-κB.

Keywords: intracerebral hemorrhage, dopamine D2 receptor, neuroinflammation, αB-crystalline, NF-κB

Introduction

Spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) is a fatal stroke subtype that accounts for approximately 15% of all strokes with highest morbidity and mortality rates1. Numerous studies have demonstrated that pronounced inflammatory reaction play an important role in the secondary brain injury after ICH, including microglial activation and neutrophil infiltration2–4. After ICH, various stimuli could activate microglia and initiate inflammatory response, such as thrombin and glutamate, which activate microglia and subsequently release pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines to enhance neuroinflammation2,5. Therefore, the strategy based on inhibition of microglia activation might provide therapeutic potential for ICH6.

The dopamine D2 receptor, a member of the rhodopsin-like heptahelical receptor family, is an important target for anti-Parkinsonian drugs that ameliorate the motor deficits7. Recent studies have demonstrated the presence of dopamine receptors in immune cells 8 and in glial cells9. Increasing evidence indicated a protective role for DRD2 agonists in regulating immune functions and inflammatory reaction, which is probably through inhibiting activated T cell proliferation10 and cytokines secretion11. Additionally, GLC756, a novel mixed dopamine D1R antagonist and D2R agonist was shown to inhibit the release of TNF-α from activated mast cells12. Another specific DRD2 agonist, Quinpirole, suppressed neuroinflammation and protected against brain injury in a MPTP-induced mouse model of Parkinson’s disease13. However, the expression and immune function of DRD2 in central nervous system after experimental stroke have not been systemically studied.

αB-crystallin (CRYAB) is known as a small heat-shock protein with anti-inflammatory properties14–16. Although CRYAB is constitutively expressed in the lens of the eye and muscles, numerous studies indicate it can be induced in both neurodegenerative disorders and acute brain injury, including multiple scleroses17, Parkinson’s disease13, as well as ischemic stroke18. Recently, CRYAB has been shown to play a crucial role in DRD2-mediated anti-inflammation effect13. In the present study, we sought to investigate the potential role and mechanisms of activation of dopamine D2 receptor in neuroinflammation after ICH; and explore the potential therapeutic utility of DRD2 agonists in collagenase and autologous blood-induced ICH models.

Materials and Methods

Animals

All animal procedures for this study were approved by the institutional animal care and use committee at Loma Linda University. Eight-week-old male CD1 mice (weight=30g, Charles River, Wilmington, MA) were housed in a 12-hour light/dark cycle at a controlled temperature and humidity with unlimited access to food and water.

ICH Model

The general procedures for inducing ICH by intrastriatal injection of either bacterial collagenase (0.075 U dissolved in 0.5μl of PBS) or autologous arterial blood (30μl) into the basal ganglia were performed as described in previous publications4, 19.

Experimental Design (Supplemental Figure I)

The experiment was designed as follows.

Experiment I (Supplemental Figure I)

To determine the time course of DRD2 and αB-crystallin after ICH, Western blot analysis for DRD2 expression were performed in ipsilateral/right hemisphere of each group at 6, 12 hours, days 1, 3, 5, and 7 after ICH insult, n=5 each time point.

Experiment II (Supplemental Figure I)

Negative control siRNA (si-NC) or DRD2 siRNA was intracerebroventricularly injected 48 hours before ICH modeling in sham and ICH group. Modified Garcia Test and Forelimb Placement Test were performed at 24 hours after ICH, n=8 each group. Western blots of ipsilateral hemisphere were conducted at 24 hours after ICH in all groups, n=5 each group. In sham, ICH+si-DRD2 and ICH+si-NC group, the Proteome Profiler™ Mouse Cytokine Array was performed 24 hours after ICH insult, n=3 each group.

Experiment III (Supplemental Figure I)

For outcome evaluation, mice were randomly divided into six groups: Sham, ICH +Vehicle (sterile saline), ICH +Quinpirole (1 or 5 mg/kg) and ICH +Ropinirole (5 mg/kg). For treatment, Two D2 receptor agonist Quinpirole (1 or 5 mg/kg) and Ropinirole (5 mg/kg) were administered by daily intraperitoneal injection starting at 1 hour post-ICH, n=6/8 each group. Neurobehavioral functions (Modified Garcia Test and Forelimb Placement Test) and brain edema were evaluated at 24 and 72 hours following ICH. In Sham, ICH +Vehicle and ICH + Quinpirole (5 mg/kg) groups, Double immunohistochemistry staining of IBA-1 and GFAP were also performed, n=4 each group.

Experiment IV (Supplemental Figure I)

Negative control siRNA (si-NC) or CRYAB siRNA (si-CRYAB) was intracerebroventricularly injected 48 hours before ICH modeling, and then followed by Quinpirole (5 mg/kg) treatment. Modified Garcia Test, Forelimb Placement Test and brain water content test were performed at 24 hours after ICH, n=6/8 each group. The relative data in sham, ICH +Vehicle, and ICH+ Quinpirole (5 mg/kg) groups were shared with Experiment III. Western blots of ipsilateral hemisphere were conducted at 24 hours after ICH in all groups, n=5 each group.

Experiment V and VI (Supplemental Figure I)

The therapeutic benefits of DRD2 agonists were tested in the autologous blood injection ICH model (bICH), followed by Quinpirole (5 mg/kg) treatment.

In addition, intranasal delivery of Quinpirole (3 and 15 mg/kg) 1 hour after ICH insult was performed to investigate the clinical translational delivery of Quinpirole. Modified Garcia Test, Forelimb Placement Test and brain water content test were performed at 24 hours after ICH, n=6/7 each group.

Intranasal Administration of Quinpirole

Intranasal administration was performed as previous reported20: mice were placed on their backs and administered either saline, Quinpirole (3 mg/kg), or Quinpirole (15 mg/kg) in nose drops (5 μL/drop) over a period of 20 mins, alternating drops every 2 minutes between the left and right nares. For studies of neuroprotection, the total volume delivered was 50 μL 1h after initiating ICH, starting at a dose 3 mg/kg which is similar to the previously identified protective dose of dopamine by intranasal administration (3 mg/kg).

In vivo RNAi

Both for DRD2 and CRYAB in vivo RNAi, a set of three different Ambion® In Vivo siRNA mixture were applied by intraventricular injection (I.C.V) as previously described4. The mouse DRD2-siRNA and CRYAB-siRNA (0.1nmol, stealth siRNA, Life Technologies) and negative control (0.1nmol) siRNA were delivered into the ipsilateral ventricle after diluted with Lipofectamine 2000 (Life Technologies) according to the manufacturer’s protocol.

Neurobehavioral Function Assessment

Neurobehavioral functions were evaluated by a 21-point score system named Garcia Test and another 10-point score system named forelimb placement test as previously reported4, 19. Two trained investigators who were blinded to animal groups performed test and the mean score of the subscales was the final score of each mouse. In blood injection model, the sensorimotor Garcia test has been modified with a maximum neurologic score at 12 (healthy animal).

Measurement of Brain Water Content

The brain water content (BWC) was measured as previously reported19.

Hematoma Volume

Hematoma volume was analyzed by hemoglobin assay 24 hours after ICH operation. Ipsilateral hemispheres were homogenized for 60 s in 3 mL of distilled water. The homogenized specimens were centrifuged (30 min, 12,000 rcf) and 80 μL of Drabkin’s reagent (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO) was added into 20 μL of supernatant in the 96-well microplate. After 15 min incubation, the hemoglobin absorbance was measured spectrophotometrically at a wavelength of 540 nm, and quantified using a standard curve. Results were presented as μL of blood.

Proteome ProfilerTM Mouse Cytokine Array

Protein expression analysis of sham or DRD2 RNAi group (si-RD2) or negative control group (si-NC) was performed 24 hours after ICH insult using the Proteome Profiler™ Antibody Arrays--Mouse Cytokine Antibody Array, Panel A (R&D Systems, Catalog # ARY006) according to the manufacturer’s instructions and previous reported21. The antibody array detects the relative levels of 40 different cytokines, chemokines in a single sample.

Western Blotting

Western Blotting was performed as previously described22. Nuclear proteins were extracted by NE-PER Nuclear and Cytoplasmic Extraction Reagents (Pierce Biotechnology, Rockford, IL), following instruction manual. Primary antibody used in this study: anti-DRD2, anti-αB-crystallin (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA), anti-IL-1β, anti-MCP-1, (Abcam, Cambridge, MA). β-actin was used as an internal loading control. Appropriate secondary antibody were all from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; ECL Plus kit (Amersham Bioscience, Arlington Heights, IL).

Co-Immunoprecipitation assay (Co-IP)

A Pierce CO-IP Kit (Thermo Scientific) was used for examination of the change in association between CRYAB and NF-κB p65 in the ipsilateral hemisphere 24 hours after ICH. A general procedure was followed using the manufacturer’s guidelines as previously described23. Protein extracts were precipitated by an anti-CRYAB or an anti-NF-κB p65 antibody, and then the precipitated protein was evaluated by western blot using anti-NF-κB p65 or an anti-CRYAB antibody. IB assay for CRYAB or NF-κB p65 was used as a loading control.

Immunofluorescence Staining

Immunofluorescence staining for brain was performed on fixed frozen section as previously described22. Coronal brain sections (10 μm) were obtained with the help of cryostat (Leica CM3050S-3-1-1, Bannockburn, IL) and permeabilized with 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS for 30 min. Sections were blocked with 5% donkey serum for 1 hour and incubated at 4°C overnight with primary antibodies: anti-Iba-1 (Abcam, Cambridge, MA) and anti-DRD2, anti-GFAP (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) followed by incubation with appropriate fluorescence conjugated secondary antibodies (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA) for 2 hours at room temperature. Activated microglia/macrophages were counted in 3 different fields immediately adjacent to the hematoma in at least 3 sections/animal using a magnification of ×400 magnification over a microscopic field of 0.01 mm2 and data was expressed as cells/mm2. Four mice/group /time point were used for quantification by an observer blinded to the experimental treatment24.

Statistical Analysis

Analysis was performed using GraphPad Prism software and all data was expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean. Student t test and 1-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Scheffe post hoc test were used to compare differences between 2 and ≥3 groups, respectively. Two-way ANOVA was performed to analyze the effects of multiple comparisons followed by Student-Newman-Keuls test. Statistically significance was defined as p < 0.05. We used the Kruskal-Wallis One Way Analysis of Variance on Ranks, followed by the Steel-Dwass multiple comparisons tests.

Results

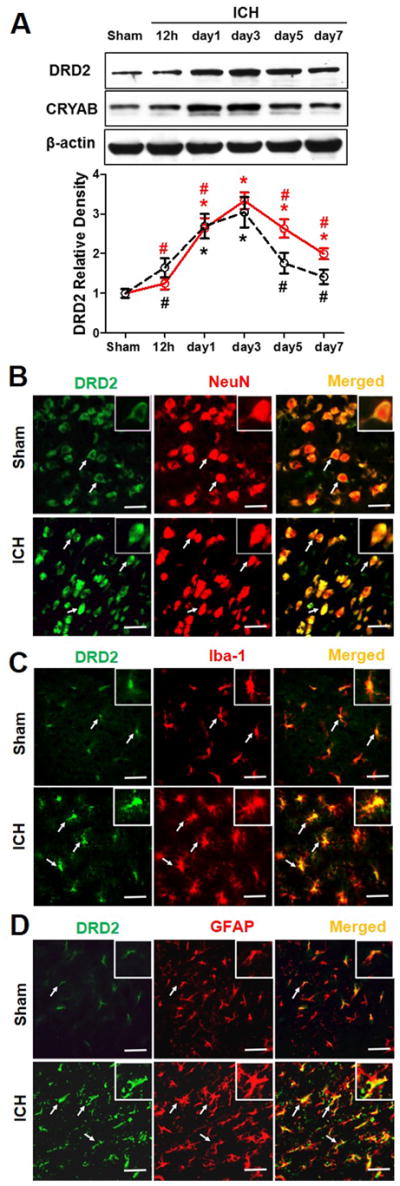

Endogenous Dopamine D2 Receptor Was Up-regulated Following ICH Injury

We first investigated whether DRD2 alterations would respond to brain injury following ICH. As shown in Figure 1, DRD2 level (Fig 1A) was significantly increased as early as 24 hours post-ICH with a peak around 72 hours (p<0.05), and remained at high levels till day 7 when compared with sham (p<0.05; Fig 1A). Accordingly, CRYAB was also significantly increased from day 1 and reached peak at day 3 (p<0.05; Fig 1B). Furthermore, the DRD2 immunoreactivity increased on neurons (D2R/NeuN) (Fig. 1B), the resident immune cells, microglia (D2R/Iba-1) (Fig. 1C) and astrocytes (D2R/GFAP) (Fig. 1D) in the perihemorrhage area 24 hours after ICH.

Figure 1.

Expression time curve of DRD2 and CRYAB following intracerebral hemorrhage injury. (A) Western blot assay for the profiles of DRD2 and CRYAB expression in the ipsilateral hemisphere in sham and ICH mice 12, 24, 72 hours, 5 days and 7 days following operation; n=5 mice per group, per time point. Relative densities have been normalized against the sham group and Error bars represent mean±SEM. *: p < 0.05 vs Sham; #: p < 0.05 vs ICH (72 hours). Representative photographs of immunofluorescence staining for DRD2 (green) expression in neurons (NeuN, red) (B), microglias (Iba-1, red) (C) and astrocytes (GFAP, red) (D) in sham and the perihematomal area 24 hours following ICH, Bar=20 μm.

DRD2 in vivo knockdown Aggravated Neurobehavioral Deficits and Pronounced Inflammatory Response Post-ICH

To identify the physiological function of endogenous DRD2 following ICH injury, the in vivo RNAi for DRD2 were performed and the silencing efficacy was confirmed by Western blot (Supplemental Figure IIA). The animals pretreated with si-DRD2s developed more severe sensorimotor deficits on modified Garcia test and forelimb placement test compared to negative control group (p < 0.05 respectively, Fig. 2A, 2B). Based on the “proteome-profiler mouse cytokine array” analysis, we obtained a list of 13 upregulated target proteins in ICH groups compared with sham (Figure 2C, 2D). Of these candidates, significantly increased cytokines (IL-1α, IL-1β, IL-16, TNF-α) and chemokines (ICAM-1, CXCL9, CXCL10, CXXL11, M-CSF, TIMP-1 and MCP-1) were observed in si-DRD2 groups compared with negative control animals (Fig. 2D). Of these candidate cytokines, we chose IL-1β and MCP-1 for the following study.

Figure 2.

DRD2 in vivo knockdown aggravated neurobehavioral deficits and pronounced inflammatory response post-ICH. Statistical analysis of Garcia test (A) and forelimb placing test (B) in scramble siRNA group (si-NC) and DRD2 siRNA group (si-DRD2) 24 h following operation; n=8, *p < 0.05 vs si-NC. (C) Representative bands of the proteome-profiler mouse cytokine array in indicated groups. (D) Quantitative analyses of detected cytokines by cytokine array, relative densities have been normalized against the sham; n=3, *: p < 0.05 vs Sham; #: p < 0.05 vs si-NC.

Dopamine D2 Receptor Agonists Treatment improved neurobehavioral outcomes and reduced brain water content both at 24 and 72 hours after ICH

Two D2 receptor agonists Quinpirole (1 or 5 mg/kg) and Ropinirole (5 mg/kg) were administered by daily intraperitoneal injection starting at 1 hour post-ICH. At 24 h after surgery, mice subjected to ICH presented a significantly worse Garcia test performance (p < 0.05, Fig. 3A) as well as increased perihematomal brain water content in the ipsilateral basal ganglia (ipsi-BG) (p < 0.05, vs sham, Fig. 3B); however, in both Quin-1 mg/kg and Quin-5 mg/kg groups, the Garcia test score were significantly improved (p < 0.05 respectively, vs. vehicle; Fig. 3A) and perihematomal brain edema were reduced (p < 0.05 respectively, vs. vehicle; Fig 3B). Another D2 receptor agonist, Ropinirole (5 mg/kg) also significantly improved the Garcia test performance (p < 0.05, vs vehicle; Fig. 3A) and reduced brain water content in ipsi-BG (p < 0.05, vs vehicle; Fig. 3B). Overall, high dosage of Quinpirole (5 mg/kg) seems more effective among the pharmacological treatments and it was used for all following experiments.

Figure 3.

Exogenous DRD2 agonists ameliorated neurobehavioral deficits, brain water content and suppressed microglia activation both at 24 and 72 hours after ICH. (A)Statistical analysis of Garcia test in indicated groups at 24 and 72 hours after ICH, n=6/8, *: p < 0.05 vs sham, #: P<0.05 vs vehicle. (B, C) Brain water content assessment at 24 hours (B) and 72 after ICH hours (C); Two-way ANOVA test, *: P<0.05 vs sham, #: P<0.05 vs vehicle. (D) Photomicrographs represent activated microglia/macrophages in the perihematomal region at 24 and 72 hours after ICH. Boxes in the upper panel are respectively magnified to the lower panel. Statistic graph shows the quantification of Iba-1+ cells in the perihematomal region, 12 fields/group, *: p < 0.05, vs vehicle.

We also evaluated neurobehavioral function and brain edema at the delayed stage (72 hours) post ICH using the Quinpirole 5 mg/kg. The results demonstrated that Quin-5 mg/kg could significantly ameliorated neurofunctional deficits and reduced perihematomal brain water content in the ipsilateral basal ganglia compared to vehicle group (p < 0.05, Fig. 3A, B).

Quinpirole Suppressed Microglia Activation and Macrophage Infiltration both at 24 and 72 hours after ICH

To study the potential role of DRD2 in neuroinflammation, we visualized microglia/macrophages recruited to the ICH using ionized calcium binding adaptor molecule 1 (Iba-1), a microglia/macrophage marker. Iba-1+ cells showed large cell bodies and short processes in 24 hours after ICH, indicating the transformation toward an activated state. Additionally, activated microglia was observed increased slightly and accumulated in the border zone surrounding the hematoma 24 hours after ICH and more strong intensity of the Iba-1+ cells at 72 hours after ICH (Figure 3C). However, infusion of Quinpirole 5 mg/kg lead to a dramatic reduction of activated microglia/macrophages, as evidenced by a decreased quantification of Iba-1+ cells in the perihematomal region compared with vehicle both at 24 and 72 hours after ICH (p < 0.05, 12 fields/group; Fig. 3D).

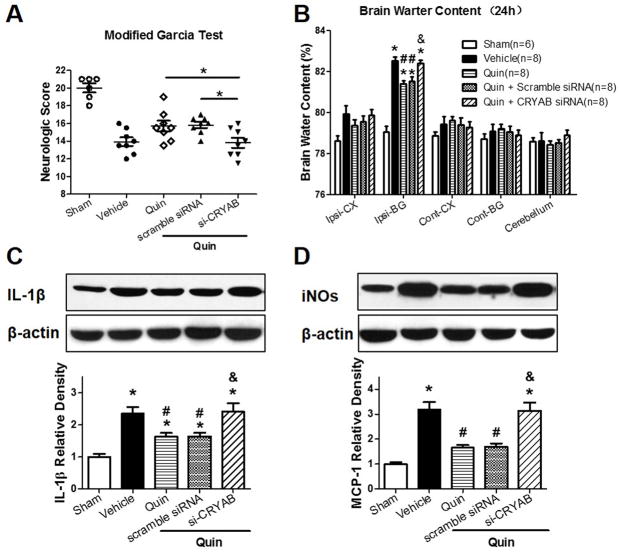

CRYAB in vivo Knockdown Abolished the Protective Effect of Quinpirole on Neuroinflammation Inhibition Following ICH

CRYAB in vivo Knockdown were preformed to investigate the potential role of CRYAB in the protective effects of DRD2 activation, the knockdown efficiency was validated by Western blot (Supplemental Figure IIB). Pretreated with si-CRYABs sufficiently abolished the protective effective of Quinpirole (5mg/kg) as shown in modified Garcia test (Fig 4A) and brain water content (Fig 4B) when compared to Quinpirole treatment group with or without control siRNAs.

Figure 4.

CRYAB in vivo knockdown abolished the attenuation on neuroinflammation by DRD2 at 24 hours following ICH. (A) the Modified Garcia test and (B) Brain water content after using pretreated CRYAB siRNAs in Quinpirole treatment groups after ICH, n=6/8. (C, D) Representative bands and quantification of IL-1β(C)and MCP-1(D) expression in indicated groups 24 hours after ICH. Relative densities have been normalized against the sham group. n=5, *: P<0.05 vs Sham; #: P<0.05 vs ICH+Vehicle; and &: P<0.05 vs ICH+scramble siRNA.

Furthermore, Western blot results showed that mice displayed dramatic increase in IL-1β and MCP-1 expression compared to sham. On the contrary, Quinpirole 5mg/kg treatment attenuated the expression of IL-1β and MCP-1, compared to vehicle (p < 0.05, respectively, Fig. 4C, 4D), which was abolished by pretreatment with si-CRYABs, while scrambled siRNA did not show those effects (Figure 4C, 4D).

Administration of Quinpirole 5 mg/kg and Ropinirole (5 mg/kg) did not affect the hemorrhage volume at 24h after ICH (P=0.9898, Supplemental Figure III).

More cytoplasmic CRYAB Co-immunoprecipitated With NF-κB p65 in Quinpirole treated mice 24 hours Following ICH

Co-immunoprecipitation (Co-IP) was performed to investigate the physical interaction between CRYAB and NF-κB p65 subunit in the ipsilateral hemisphere after ICH. Co-IP using CRYAB antibody, more NF-κB p65 were detected in Quinpirole group, while si-CRYABs abolished this effect (p < 0.05, vs vehicle, Fig 5A). On the other hand, Co-IP using NF-κB p65 antibody showed an increase in the CRYAB intensity (p < 0.05, vs vehicle, Fig 5B), which confirmed the enhanced binding activity between CRYAB and NF-κB p65 after Quinpirole treatment (Fig 5A, 5B). However, no change in IkB-a expression (the negative regulator of NF-κB) was seen between vehicle and Quinpirole groups (Supplemental Figure IV).

Figure 5.

Quinpirole attenuated the nuclear translocation of NF-κB via enhanced cytoplasmic binding activity with CRYAB. (A, B) Immunoprecipitation assay (IP) bands for interaction between CRYAB and NF-κB. IP for NF-κB with CRYAB antibody (A) and IP for CRYAB with NF-κB antibody(B) in indicated groups; The precipitated protein was evaluated by western blot. Statistic graphs show the quantifications of relative densities representatively. Representative bands and quantifications of NF-κB p65 expression in cytoplasmic (C), and nucleic (D) proteins in indicated groups at 24 hours after ICH. n=5, *: P<0.05.

Quinpirole Attenuated NF-κB nuclear translocation via enhanced cytoplasmic binding activity with CRYAB

The nucleic expression of NF-κB p65 was significantly increased at 24 hours after ICH (Figure 5D), Quinpirole preserved the expression levels of NF-κB p65 in cytoplasmic fraction and decreased the nuclear portion of NF-κB p65 levels when compared with vehicle groups (Figures 5C, 5D). si-CRYABs pretreatment abolished the reduced nuclear transportation, compared with Quinpirole group; the scrambled siRNAs did not show those effects (Figure 5C, 5D).

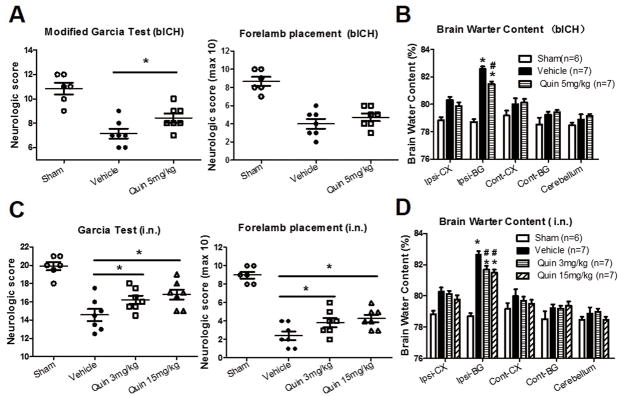

Quinpirole Treatment Reduced the Behavior Deficits and Brain Edema 24 hours after the Autologous Blood Injection ICH Model

Except testing the therapeutic benefits of DRD2 agonists in the collagenase-induced ICH model, DRD2 agonists were tested also in the autologous blood injection ICH model (bICH). The results showed that Quinpirole (5 mg/kg)-treated mice performed markedly better in the modified Garcia test compared with vehicle group (P < 0.05, Fig 6A). In addition, Quinpirole (5 mg/kg) treatment groups had significant reduced brain edema accumulations in the ipsilateral basal ganglia compared with vehicle 24 hours after bICH (P < 0.05, Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

Therapeutic effects of Quinpirole in autologous blood injection ICH model and in intranasal drug delivery condition. Quinpirole improved modified Garcia score and forelimb placing score (A) and reduced Brain water content (B) in an autologous blood ICH model 24 hours post ICH, n=7. (C, D) Intranasal delivery of Quinpirole (both 3 mg/kg and 15 mg/kg) improved modified Garcia score and forelimb placing score (C) and reduced Brain water content (D) 24h after ICH insult. (A, C)*P<0.05; (B, D) *P<0.05 vs sham; #p < 0.05 vs Vehicle.

Intranasal Delivery of Quinpirole Ameliorated Neurological Deficits and Brain Edema at 24h after ICH

To investigate the clinical translational treatment with Quinpirole, two doses Quinpirole (3 and 15 mg/kg) were administered by intranasal delivery 1 hour after ICH insult. Both Quinpirole 3 mg/kg and 15 mg/kg treatments significantly improved neurobehavioral scores in the Garcia test as well as forelimb placing test 24 hours after ICH when compared with vehicle group (P < 0.05 respectively, Fig 6C). For brain water content, there was also a significant reduction in the ipsilateral basal ganglia in both Quinpirole 3 mg/kg and 15 mg/kg groups (P < 0.05 respectively, vs vehicle; Fig 6D).

Discussion

ICH is a devastating clinical event without effective therapies. Emerging evidence suggests that inflammatory mechanisms are involved in the progression of ICH-induced brain injury2, 25. This study demonstrated that dopamine D2 receptor and its essential downstream protein CRYAB were upregulated in the injured hemisphere post-ICH. Exogenous dopamine D2 receptor agonists alleviated neurological impairment, reduced microglia activation and inflammatory cytokines (IL-1βand MCP-1) production, which were associated with enhanced cytoplasmic binding activity between CRYAB and NF-κB and decreased NF-κB nuclear translocation. Additionally, we assessed the therapeutic potential and efficiency of Quinpirole by intranasal drug delivery. Taking together, these observations suggested DRD2 may be involved in controlling innate immunity in the central nervous system. DRD2 agonists may have potential to reduce neuroinflammation following ICH.

There are studies indicated a protective role for DRD2 agonists in regulating immune functions8 and inflammatory reaction26–28. Up regulation of D2 receptor was observed in the pre-infarction area after ischemic stroke29. Most recently, it was reported that the DRD2−/− mice exhibited remarkable inflammatory response with pronounced microglia activation and aberrant inflammatory mediators in Parkinson’s disease13. In our study, we observed that DRD2 was upregulated and its immunoreactivity was increased in microglia in the peri-hemorrhage area after ICH. By DRD2 in vivo knockdown, we observed aggravated neurobehavioral deficits and pronounced cytokines expression, which suggested DRD2 may contribute on immune deregulation and neuroinflammation following ICH injury. Furthermore, pharmacological treatment with two D2 receptor agonists Quinpirole (5 mg/kg) and Ropinirole (5 mg/kg) improved neurobehavioral functions, and reduced microglia hyper-activity related neuroinflammation. Consistent with our results, another dopamine D2 receptor agonist bromocriptine (BRC) were also reported to suppress glial inflammation in a model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis28.

αB-crystallin is a heat shock protein that exerts cell protection under several stress-related conditions with anti-neurotoxic17, 18 and pro-survival properties30. Recently, studies demonstrated that CRYAB is a potent negative regulator on inflammatory pathways in both neurodegenerative disorders17 and acute brain injury models18. In our study, pretreated with CRYAB siRNAs eliminated the protective effects of Quinpirole in brain edema and cytokines expression, supporting the hypothecs that CRYAB may contribute to the suppression of neuroinflammation by DRD2 agonists in experimental ICH model.

However, molecular mechanism that how CRYAB regulates inflammatory response has not been well understood. NF-κB plays a critical role in the inflammatory response by nuclear translocation and regulating the transcription of inflammatory genes. CRYAB has been indicated to modulate NF-κB signaling 31–33. However, it’s still controversial whether CRYAB negatively or positively regulate NF-κB activity. Several studies reported that CRYAB enhanced NF-κB activity32. Another study showed that CRYAB-dependent NF-κB activation protected myoblasts from TNF-α induced cytoxicity31. In addition, another study indicated that CRYAB probably suppresses the inflammatory role of NF-κB in astrocytes during autoimmune demyelination, with the enhancement NF-κB p65 DNA binding activity in Cryab−/− mice17. Consistent with this report, we elucidated the mechanism that CRYAB negatively modulated NF-κB activity by directly binding with cytoplasmic NF-κB p65, by using Co-immunoprecipitation method. In addition, we also found that enhanced cytoplasmic binding activity between CRYAB and NF-κB p65 in Quinpirole-treated group, which reduced its nuclear transportation and the transcription of pro-inflammatory cytokines. These observations may help to explain how DRD2 activation could suppress neuroinflammation after ICH injury.

One important issue is how DRD2 agonists suppressed the microglia activation? Previous studies and our own results demonstrated that DRD2 were expressed on several cell types, not only microglia but also neuron and astrocyte9, 29. In this study, we demonstrated that the dopamine agonists directly activated DRD2 on microglia and suppressed the CRYAB/ NF-kB inflammatory pathway, which initiates the microglia activation. However, we could not exclude a potential indirect suppression on microglia activation by DRD2 through preventing neuron apoptosis or the activation of astrocytes. Further studies are needed to verify this important issue.

In conclusion, the present study demonstrated that dopamine D2 receptor elevation occurred after ICH in brain tissues, and exogenous DRD2 agonists inhibited neuroinflammation and improved neurological outcome, which was probably mediated by αB-crystallin and enhanced cytoplasmic binding activity with NF-κB. This novel observation indicated an endogenous physiology role of glial dopamine D2 receptor on microglia innate immunity and neuroinflammation following ICH. DRD2 agonists have potentials to reduce neuroinflammation and decrease secondary brain injury following ICH. It should be noted that previous studies indicated D2 receptor agonists have anti-apoptosis property34 and may be involved in neurogenesis and angiogenesis35. Therefore, further studies are needed to elucidate other mechanisms involved in the protective effect of dopamine stimulants.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sources of Funding:

This study is partially supported by grants from NIH NS082184 to JT and JHZ.

Footnotes

Disclosures:

None

References

- 1.Keep RF, Hua Y, Xi G. Intracerebral haemorrhage: mechanisms of injury and therapeutic targets. Lancet Neurol. 2012;11:720–31. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70104-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhou Y, Wang Y, Wang J, Anne Stetler R, Yang QW. Inflammation in intracerebral hemorrhage: from mechanisms to clinical translation. Prog Neurobiol. 2014;115:25–44. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2013.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang J, Dore S. Inflammation after intracerebral hemorrhage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:894–908. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ma Q, Chen S, Hu Q, Feng H, Zhang JH, Tang J. NLRP3 inflammasome contributes to inflammation after intracerebral hemorrhage. Ann Neurol. 2014;75:209–19. doi: 10.1002/ana.24070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang J. Preclinical and clinical research on inflammation after intracerebral hemorrhage. Prog Neurobiol. 2010;92:463–77. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2010.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Iadecola C, Anrather J. Stroke research at a crossroad: asking the brain for directions. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:1363–8. doi: 10.1038/nn.2953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bibb JA. Decoding dopamine signaling. Cell. 2005;122:153–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sarkar C, Basu B, Chakroborty D, Dasgupta PS, Basu S. The immunoregulatory role of dopamine: an update. Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24:525–8. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kuric E, Wieloch T, Ruscher K. Dopamine receptor activation increases glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor in experimental stroke. Exp Neurol. 2013;247:202–8. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2013.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kuric E, Ruscher K. Reduction of rat brain CD8+ T-cells by levodopa/benserazide treatment after experimental stroke. Eur J Neurosci. 2014;40:2463–70. doi: 10.1111/ejn.12598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuric E, Ruscher K. Reversal of stroke induced lymphocytopenia by levodopa/benserazide treatment. J Neuroimmunol. 2014;269:94–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2014.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laengle UW, Markstein R, Pralet D, Seewald W, Roman D. Effect of GLC756, a novel mixed dopamine D1 receptor antagonist and dopamine D2 receptor agonist, on TNF-alpha release in vitro from activated rat mast cells. Exp Eye Res. 2006;83:1335–9. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shao W, Zhang SZ, Tang M, Zhang XH, Zhou Z, Yin YQ, et al. Suppression of neuroinflammation by astrocytic dopamine D2 receptors via alphaB-crystallin. Nature. 2013;494:90–4. doi: 10.1038/nature11748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brownell SE, Becker RA, Steinman L. The protective and therapeutic function of small heat shock proteins in neurological diseases. Front Immunol. 2012;3:74. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2012.00074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Klopstein A, Santos-Nogueira E, Francos-Quijorna I, Redensek A, David S, Navarro X, et al. Beneficial effects of alphaB-crystallin in spinal cord contusion injury. J Neurosci. 2012;32:14478–88. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0923-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rothbard JB, Kurnellas MP, Brownell S, Adams CM, Su L, Axtell RC, et al. Therapeutic effects of systemic administration of chaperone alphaB-crystallin associated with binding proinflammatory plasma proteins. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:9708–21. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.337691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ousman SS, Tomooka BH, van Noort JM, Wawrousek EF, O’Connor KC, Hafler DA, et al. Protective and therapeutic role for alphaB-crystallin in autoimmune demyelination. Nature. 2007;448:474–9. doi: 10.1038/nature05935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arac A, Brownell SE, Rothbard JB, Chen C, Ko RM, Pereira MP, et al. Systemic augmentation of alphaB-crystallin provides therapeutic benefit twelve hours post-stroke onset via immune modulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:13287–92. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1107368108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Krafft PR, Caner B, Klebe D, Rolland WB, Tang J, Zhang JH. PHA-543613 preserves blood-brain barrier integrity after intracerebral hemorrhage in mice. Stroke. 2013;44:1743–7. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.000427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Topkoru BC, Altay O, Duris K, Krafft PR, Yan J, Zhang JH. Nasal administration of recombinant osteopontin attenuates early brain injury after subarachnoid hemorrhage. Stroke. 2013;44:3189–94. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.001574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fessner A, Esser JS, Bluhm F, Grundmann S, Zhou Q, Patterson C, et al. The transcription factor HoxB5 stimulates vascular remodelling in a cytokine-dependent manner. Cardiovasc Res. 2014;101:247–55. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvt244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen Y, Zhang Y, Tang J, Liu F, Hu Q, Luo C, et al. Norrin Protected Blood-Brain Barrier Via Frizzled-4/beta-Catenin Pathway After Subarachnoid Hemorrhage in Rats. Stroke. 2015;46:529–36. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.114.007265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jung JE, Kim GS, Chan PH. Neuroprotection by interleukin-6 is mediated by signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 and antioxidative signaling in ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2011;42:3574–9. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.626648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang J, Tsirka SE. Tuftsin fragment 1–3 is beneficial when delivered after the induction of intracerebral hemorrhage. Stroke. 2005;36:613–8. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000155729.12931.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Xi G, Keep RF, Hoff JT. Mechanisms of brain injury after intracerebral haemorrhage. Lancet Neurol. 2006;5:53–63. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(05)70283-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Peiser C, Trevisani M, Groneberg DA, Dinh QT, Lencer D, Amadesi S, et al. Dopamine type 2 receptor expression and function in rodent sensory neurons projecting to the airways. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2005;289:L153–8. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00222.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Iravani MM, Sadeghian M, Leung CC, Tel BC, Rose S, Schapira AH, et al. Continuous subcutaneous infusion of pramipexole protects against lipopolysaccharide-induced dopaminergic cell death without affecting the inflammatory response. Exp Neurol. 2008;212:522–31. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tanaka K, Kanno T, Yanagisawa Y, Yasutake K, Hadano S, Yoshii F, et al. Bromocriptine methylate suppresses glial inflammation and moderates disease progression in a mouse model of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Exp Neurol. 2011;232:41–52. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2011.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruscher K, Kuric E, Wieloch T. Levodopa treatment improves functional recovery after experimental stroke. Stroke. 2012;43:507–13. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.638767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Arrigo AP, Simon S, Gibert B, Kretz-Remy C, Nivon M, Czekalla A, et al. Hsp27 (HspB1) and alphaB-crystallin (HspB5) as therapeutic targets. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:3665–74. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Adhikari AS, Singh BN, Rao KS, Rao Ch M. alphaB-crystallin, a small heat shock protein, modulates NF-kappaB activity in a phosphorylation-dependent manner and protects muscle myoblasts from TNF-alpha induced cytotoxicity. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2011;1813:1532–42. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2011.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dieterich LC, Huang H, Massena S, Golenhofen N, Phillipson M, Dimberg A. alphaB-crystallin/HspB5 regulates endothelial-leukocyte interactions by enhancing NF-kappaB-induced up-regulation of adhesion molecules ICAM-1, VCAM-1 and E-selectin. Angiogenesis. 2013;16:975–83. doi: 10.1007/s10456-013-9367-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mercatelli N, Dimauro I, Ciafre SA, Farace MG, Caporossi D. AlphaB-crystallin is involved in oxidative stress protection determined by VEGF in skeletal myoblasts. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010;49:374–82. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2010.04.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nair VD, Olanow CW, Sealfon SC. Activation of phosphoinositide 3-kinase by D2 receptor prevents apoptosis in dopaminergic cell lines. Biochem J. 2003;373:25–32. doi: 10.1042/BJ20030017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mirones I, Angel Rodríguez-Milla M, Cubillo I, Mariñas-Pardo L, de la Cueva T, Zapata A, et al. Dopamine mobilizes mesenchymal progenitor cells through D2-class receptors and their PI3K/AKT pathway. Stem Cells. 2014;32:2529–38. doi: 10.1002/stem.1745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.