Abstract

Innovative models to facilitate more rapid uptake of research findings into practice are urgently needed. Community members who engage in research can accelerate this process by acting as adoption agents. We implemented an Evidence Academy conference model bringing together researchers, health professionals, advocates, and policy makers across North Carolina to discuss high-impact, life-saving study results. The overall goal is to develop dissemination and implementation strategies for translating evidence into practice and policy. Each one-day, single-theme, regional meeting focuses on a leading community-identified health priority. The model capitalizes on the power of diverse local networks to encourage broad, common awareness of new research findings. Furthermore, it emphasizes critical reflection and active group discussion on how to incorporate new evidence within and across organizations, health care systems, and communities. During the concluding session, participants are asked to articulate action plans relevant to their individual interests, work setting, or area of expertise.

Introduction

New knowledge that affects prevention, clinical care, and health policy is abundant, yet timely adoption of research findings into practice remains challenging.1 Educational opportunities that expose providers and practitioners to current research findings may increase use of evidence-based practices.2 Likewise, opportunities that expose investigators to local practice environments may increase production of more relevant research.3 Current research dissemination strategies, including professional meetings, continuing medical education4, and peer-reviewed publications1 tend to be unidirectional (researcher to audience) and fail to address tensions between scientifically rigorous protocols and real-world application. While knowledge transfer may occur, translation of evidence into practice also requires feasible local implementation strategies. We created a low-cost, regional conference model to: (1) increase access to research results and evidence-based practices; (2) facilitate structured, in-depth discussion among participants; (3) encourage networking and collaborations; and (4) engage stakeholders in creating follow-up action plans.

The Evidence Academy Model

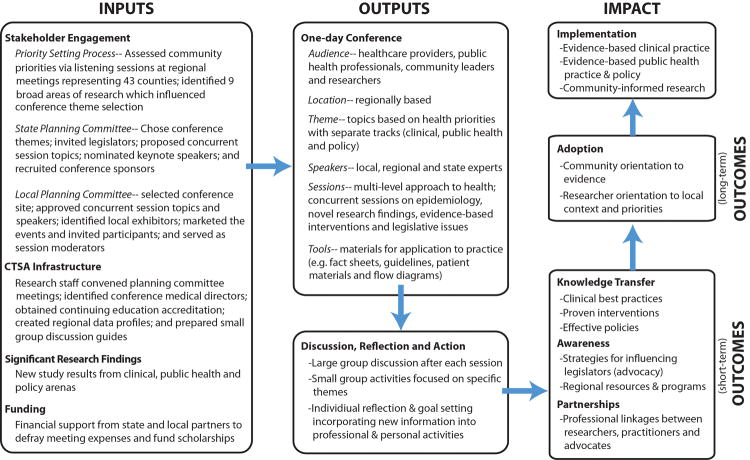

A team of academic and community partners led the creation of the “Evidence Academy” educational model (Figure 1). An Evidence Academy differs from a conventional conference by creating a co-learning experience for a relatively small, well-defined network of individuals who represent different sectors but share a collective interest in a specific health priority. Evidence Academies have community, clinical, and policy tracks to reach participants from different backgrounds and to encourage multilevel engagement.5 We increased access by offering scholarships and reduced time and cost by holding the events locally. Five Evidence Academies took place from 2010-2012 and were focused on colorectal cancer, breast cancer, tobacco and lung cancer, and HIV/AIDS.

Figure 1. The Evidence Academy Logic Model.

The Evidence Academy Program

State and local committee members jointly planned each conference and participated as speakers, moderators, group facilitators, and exhibitors. Multiple factors determined theme and locale: (1) health priorities identified by local stakeholders6 and epidemiological assessments, with special attention to disparities in disease incidence or outcomes; (2) recent study findings with strong implications for clinical and public health practice and policy; (3) existing gaps between evidence from clinical trials and actual practice; (4) pre-existing partnerships with healthcare and community organizations; and (5) locations with UNC regional research staff. Data profiles were created for each conference, which highlighted statistics by county or region to illustrate the potential impact of implementing research results on a local level.

Each Evidence Academy began with a data-driven overview of the topic followed by breakout sessions. Speakers included researchers, practitioners, legislators, advocates, and community members affected by the health condition. They highlighted findings from such landmark studies as the HIV Prevention Network Trial 0527, the National Lung Screening Trial8, and the Carolina Breast Cancer Study.9 Other presenters emphasized making informed treatment decisions, promoting evidence-based policy, systems, or environmental changes, tailoring evidence-based interventions to address local conditions, and developing multi-level partnerships to facilitate the translation of research into practice. Afternoon sessions included panel discussions and facilitated small group roundtables where participants proposed follow-up activities based on the conference content. These discussions incorporated adult learning principles such as critical reflection because participants were asked to contemplate how the information was applicable to their own work, and what action steps could be taken after the conference.

Evaluation

Process data were collected at each Evidence Academy. Approximately 100 people attended each conference, including health professionals (physicians, mid-level providers, specialty nurses, RNs), community members, and researchers. An average of 20 counties were represented by attendees at each event, indicating broad reach across the state. In post-conference evaluations, participants indicated on a 1 to 5 scale that the conference content was consistent with course objectives (4.57); the content would improve their ability to provide appropriate prevention, screening, and treatment services (4.48); and the panel discussions helped illustrate practical ways of establishing partnerships across research, practice, and care (3.93). When asked how the information would be used, attendees gave examples of how they would more effectively counsel clients or patients on tobacco cessation (by providing “patient education that smoking causes more than just lung cancer”) or HIV testing (by ensuring “we enhance our HIV education and prevention strategies based [on]…information provided in today's training”). They remarked on opportunities for increased activism (“further advocacy for tobacco free policies and continued funding”) and ways to support funding or specific regulations to help address issues affecting their communities (“use the youth to advocate as much as possible”).

Ongoing informal communication with attendees revealed longer-term impacts. We observed how the Evidence Academies influenced the adoption of best practices at the community level. After the Colorectal Cancer Evidence Academy, an attendee from the state primary care association initiated a 50th birthday card intervention at a community health center for patients due for colorectal cancer screening. After the Breast Cancer Evidence Academy, a regional cancer coalition convened strategic planning meetings and prioritized two topics: 1) improving referral systems across county lines and across the cancer care continuum and 2) provider education, especially to improve the quality of patient-provider interactions in rural, African American communities. The coalition developed a detailed resource manual describing patient support resources across several counties and sponsored a follow-up conference on improving patient-provider communication.

Next Steps

A limitation of the current Evidence Academy model is the lack of formal long-term evaluation to determine exactly how participants incorporated new learning into practice over time. For our next conference, we are incorporating an “action learning cohort series”, an ongoing forum where local stakeholders will come together to plan and create products related to policy, practice, or research. The cohort will receive mentoring, participate in 4-5 interactive seminars, and work closely with new partners to improve community health.

Conclusion

The Evidence Academies clearly empowered community members to integrate new study findings into their daily work, and enabled researchers to connect with and learn from attendees. Academic health centers should “be creative in translating and disseminating findings and information to the community…and think of dissemination as a cyclical, recursive, and dynamic process that … effect(s) change.”3 The Evidence Academy model is one strategy to expand the borders of translational research and incorporate community partners to achieve better health outcomes.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Dr. Ashonda Assad, Dr. Mark Petruzziello and Dr. Sam Cykert for serving as Medical Directors; Xavier McCutcheon and Lori Smith for providing logistical support; Michelle Maclay and Shaina Schreuder for providing communications support; and the many community-based organizations across North Carolina that contributed to our events.

Funding: Funding for the Evidence Academies was provided by the following: (1) The University Cancer Research Fund, UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, (2) North Carolina Translational and Clinical Science Institute, grant award #1UL1TR001111 from the National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), National Institutes of Health, (3) Comprehensive Cancer Control Collaborative of North Carolina, Cooperative Agreement #U48-DP000059 from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, (4) Southeastern U.S. Collaborative Center of Excellence in the Elimination of Disparities, grant award #U58-DP000984 and #U48-DP001907 from the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Footnotes

Credits: None

Disclaimers: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

Catherine L. Rohweder, Consortium for Implementation Science, Department of Health Policy and Management, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC.

Jane L. Laping, NC Translational and Clinical Sciences Institute, retired, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC.

Sandra J. Diehl, NC Translational and Clinical Sciences Institute, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC.

Alexis A. Moore, UNC Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC.

Malika Roman Isler, Department of Social Medicine, UNC School of Medicine, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC.

Jennifer Elissa Scott, Consortium for Implementation Science, Department of Health Policy & Management, Gillings School of Global Public Health, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC.

Zoe Kaori Enga, NC Translational and Clinical Sciences Institute, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC.

Molly C. Black, Primary Care Systems, South Atlantic Division, American Cancer Society, Asheville, NC.

Gaurav Dave, Department of Medicine, UNC School of Medicine, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC.

Giselle Corbie-Smith, Department of Social Medicine and Medicine, UNC School of Medicine, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, NC.

Cathy L. Melvin, Department of Public Health Sciences, Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, SC.

References

- 1.Coomarasamy A, Gee H, Publicover M, Khan KS. Medical journals and effective dissemination of health research. Health Info Libr J Dec. 2001;18(4):183–191. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2532.2001.00349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lizarondo L, Grimmer-Somers K, Kumar S. A systematic review of the individual determinants of research evidence use in allied health. J Multidiscip Healthc. 2011;(4):261–272. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S23144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Michener L, Cook J, Ahmed SM, et al. Aligning the Goals of Community-Engaged Research: Why and How Academic Health Centers Can Successfully Engage with Communities to Improve Health. Acad Med. 2012;87(3):285–291. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182441680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grimshaw J, Eccles MP, Lavis JN, Hill SJ, Squires JE. Knowledge translation of research findings. Implement Sci. 2012;7:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-7-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones L, Wells K. Strategies for academic and clinician engagement in community-participatory partnered research. JAMA. 2007 Jan 24;297(4):407–410. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.4.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jones B, Lightfoot A, De Marco M, Isler MR, Ammerman A, Nelson D, Harrison L, Motsinger B, Melvin C, Corbie-Smith G. Community-responsive research priorities: Transforming health research infrastructure. Prog Community Health Partnersh. 2012;6(3):339–48. doi: 10.1353/cpr.2012.0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cohen M, McCauley M, Gamble T. HIV treatment as prevention and HPTN 052. Current Opinion in HIV and AIDS. 2012;7(2):99–105. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32834f5cf2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.The National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Reduced Lung-Cancer Mortality with Low-Dose Computed Tomographic Screening. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:395–409. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Millikan RC, Newman B, Tse CK, Moorman PG, Conway K, Dressler LG, Smith LV, Labbok MH, Geradts J, Bensen JT, Jackson S, Nyante S, Livasy C, Carey L, Earp HS, Perou CM. Epidemiology of basal-like breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2008 May;109(1):123–39. doi: 10.1007/s10549-007-9632-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]