Abstract

Introduction

Coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery is a well-established, commonly performed treatment for coronary artery disease—a disease that affects over 10% of US adults and is a major cause of morbidity and mortality. In 2005, the mean cost for a CABG procedure among Medicare beneficiaries in the USA was $32 201±$23 059. The same operation reportedly costs less than $2000 to produce in India. The goals of the proposed study are to (1) identify the difference in the costs incurred to perform CABG surgery by three Joint Commission accredited hospitals with reputations for high quality and efficiency and (2) characterise the opportunity to reduce the cost of performing CABG surgery.

Methods and analysis

We use time-driven activity-based costing (TDABC) to quantify the hospitals’ costs of producing elective, multivessel CABG. TDABC estimates the costs of a given clinical service by combining information about the process of patient care delivery (specifically, the time and quantity of labour and non-labour resources utilised to perform each activity) with the unit cost of each resource used to provide the care. Resource utilisation was estimated by constructing CABG process maps for each site based on observation of care and staff interviews. Unit costs were calculated as a capacity cost rate, measured as a $/min, for each resource consumed in CABG production. Multiplying together the unit costs and resource quantities and summing across all resources used will produce the average cost of CABG production at each site. We will conclude by conducting a variance analysis of labour costs to reveal opportunities to bend the cost curve for CABG production in the USA.

Ethics and dissemination

All our methods were exempted from review by the Stanford Institutional Review Board. Results will be published in peer-reviewed journals and presented at scientific meetings.

Keywords: HEALTH ECONOMICS

Strengths and limitations of this study.

Time-driven activity-based costing (TDABC) is a bottoms-up costing approach based on the actual clinical and administrative processes used at each site. Its detailed process maps and unit costs allow for granular comparison of the cost of producing coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) across multiple sites.

The multisite study design enables us to compare the CABG production processes across three hospitals that follow different strategies for their CABG procedures. We will identify how the choices made lead to differences in resource consumption and cost. The use of variance analysis across the three sites will allow us to characterise opportunities to improve CABG affordability.

We cannot independently cross-reference our data with public cost data. Within the context of this study, public cost data are neither readily available (as the healthcare industry has historically not invested in accurately measuring the actual costs of delivering patient-level care) nor are informative when available (as the costs reported in the literature use arbitrary and inaccurate ratios of costs-to-charges to allocate overall hospital costs down to specific clinical procedures).

Although the scope of the TDABC analysis is the same across the sites, structural and regulatory differences between the health systems in India and the USA may not permit some of the low cost practices in the Indian hospital to be replicated in US hospitals.

This study is unable to evaluate the extent to which each site uses different resources such as personnel, space and equipment relative to their capacity. While, in principle, TDABC does enable unused resource capacity to be estimated directly, we studied only one of the many cardiovascular surgical procedures performed at the three sites and therefore could not independently calculate or compare the quantities of unused resource capacity at each site.

Introduction

Healthcare spending accounts for about 18% of gross domestic product in the USA.1 2 Some have estimated that up to 30% of that spending is wasted due to inefficiency.3 4 In response to evidence of suboptimal outcomes against the backdrop of high and rising costs, government and private sector payers are incentivising healthcare providers to provide better health with less spending.

Coronary artery disease (CAD) affects over 10% of US adults5 and is a major cause of morbidity and mortality. Coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery is a well-established, commonly performed treatment for CAD, with nearly 400 000 procedures performed annually in the USA.6 According to the 2012 Healthcare Cost and Utilization (HCUP) Project Statistics, the mean charges for performing CABG surgery are $149 480,6 well more than an order of magnitude higher than those at international sites with equivalent outcomes.7

While charge data like those reported above are readily available, a key challenge in healthcare is accurate cost information. The healthcare industry has historically not invested in accurately measuring the specific costs of delivering patient-level care.8 9 Indeed, the widespread confusion between the dollar amount charged for medical services rendered, the dollar amount reimbursed and the cost of providing the services is a major barrier to reducing the cost of healthcare.8 A common myth is to use charges as a good surrogate for costs,8 either by multiplying total charges with cost-to-charge ratios10 or by assigning expenses to procedures and patients with relative value units. Such an approach introduces distortions and cross-subsidies among different service lines. Recently introduced government and private sector incentives are motivating healthcare providers to better understand the cost of production of various service lines.11–15 Time-driven activity-based costing (TDABC),16 17 a costing method widely employed in other sectors, such as retailing, manufacturing and financial services, has recently begun gaining traction in healthcare.18–23 In the select healthcare cases where it has been applied, TDABC has been successful at identifying and reducing unused capacity and improving resource allocation for optimal efficiency.19

We conducted a TDABC study in conjunction with three Joint Commission accredited24 25 hospitals with reputations for high quality and efficiency, two in the USA and one in Bangalore, India. The goal of the study was to compare the CABG production processes of these selected hospitals in an attempt to explain the difference in production costs between them and to characterise opportunities to improve CABG affordability in the USA.

Methods and analysis

Background on sites

We conducted a TDABC study to calculate production costs for isolated, elective, uncomplicated, multivessel CABG surgeries performed at two sites in the USA (site 1 and site 2) and one site in India (site 3). Site 1 is a multispecialty hospital and uses an integrated, systems-based approach to deliver high-quality, evidence-based, affordable care. Site 2 is a dedicated heart hospital, known for its high quality (ranking in the top 2% of all heart surgery programmes in the USA) and patient-centered care. Site 3 is one of the largest heart hospitals in the world and is notable for combining minutely detailed care protocols with an assembly line approach to care delivery.

Background on TDABC

TDABC,8 16 17 the costing methodology in this study, generates cost of production using estimates of two parameters: (1) the unit cost of resource inputs (labour and non-labour) and (2) the time and the quantity of resources required to perform a transaction or an activity. In the healthcare context, TDABC combines information about the patient care cycle for a given medical condition (eg, CABG), with the resources consumed during that care cycle. Box 1 details steps of a TDABC analysis.8

Box 1. Step by step time-driven activity-based costing analysis8.

Select the medical condition and define the care delivery cycle.

- Develop process maps with the following principles:

- Each step reflects an activity in patient care delivery,

- Identify the resources involved for the patient at each step,

- Identify any supplies used for the patient at each step.

Obtain time estimates for each process step through interviews and observations.

- Calculate the capacity cost rate (CCR) for each resource:

Calculate the total direct costs (personnel, equipment, space and supplies) of all the resources used over the cycle of care.

Identify and allocate the indirect costs attributable to the cycle of care.

Validate cost estimation with pertinent stakeholders.

TDABC begins with selecting the medical condition and defining the beginning and end of the patient care cycle. The second step is creating process maps that document every administrative and clinical process involved in the treatment of the selected medical condition. Process mapping requires observing patients through their care cycle, and conducting interviews and surveys with personnel involved in the care cycle. The final process map is a detailed document that captures all of the activities performed over the complete care cycle along with the average time, the personnel type and equipment required to complete each activity. Process mapping also identifies purchased materials, supplies, devices, implants and grafts consumed during the care cycle.

Obtaining time estimates depends on the predictability of the activity. For simple tasks, subject matter experts may provide accurate estimates. For more complex tasks, such as the procedural steps of surgery, time duration can be obtained by direct observations and extant systematic measures of time to deliver care.

Process maps also identify the resources (ie, space and equipment) used at each care activity, as well as probabilistic decision nodes to capture alternative pathways caused by individual patient characteristic variability and process variations. The estimation of the probabilities can be challenging, and frequently requires interviews with a number of different clinicians and staff to validate.

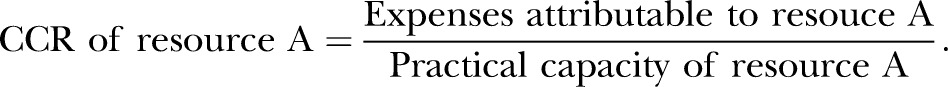

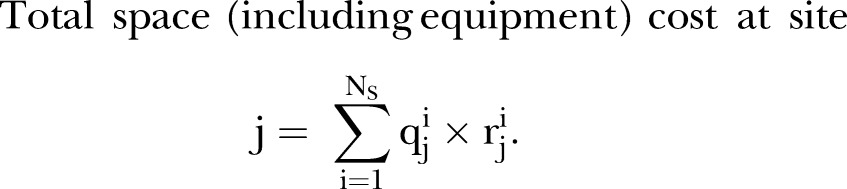

The fourth step of TDABC is to determine the capacity cost rate (CCR) for each resource consumed, that is, the cost per minute for the clinical and administrative resources—licensed and unlicensed personnel, physical space, equipment and supplies—involved in the care cycle. The simplified equation is:

|

The expenses attributable to a resource require the calculation of the total cost incurred to make the resource available for patient care. For personnel, this includes salary, fringe benefits, administrative support, information technology and office expenses. For physical space, this includes annual depreciation, maintenance, operating and housekeeping costs, real estate costs, and the cost value of all equipment in that space. The practical capacity of a resource is the number of clinical minutes that resource is available per year. For personnel, available time only includes direct time available for patients care (such as during clinical shifts) and on-call time, but does not include off-duty, vacation and holiday time, nor does it include time devoted to research, administration and medical education.

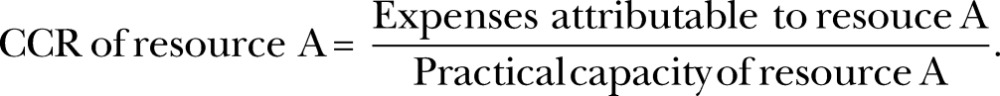

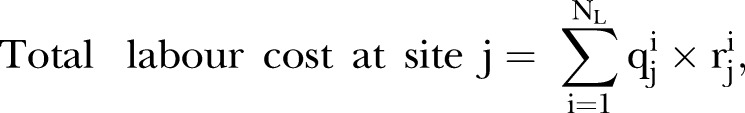

The total direct costs are then calculated in step 5 by multiplying the CCR for each resource (personnel and space) by the average minutes that resource is being used for each activity step, plus the cost of supplies and equipment consumed at that step. For the purposes of defining the calculation, let  be the CCR for resource i at site j and

be the CCR for resource i at site j and  be quantity of resource i consumed during the care cycle at site j. Furthermore, we define NL as the total resource classes of labour and NS as the total resource classes of space. To calculate labour and space (including equipment) costs, for each resource, we multiply the total utilisation of that resource obtained from the process maps with the CCR for that resource. The sum of the individual resources gives us the total cost of the labour and space resources that the site uses to perform a CABG surgery:

be quantity of resource i consumed during the care cycle at site j. Furthermore, we define NL as the total resource classes of labour and NS as the total resource classes of space. To calculate labour and space (including equipment) costs, for each resource, we multiply the total utilisation of that resource obtained from the process maps with the CCR for that resource. The sum of the individual resources gives us the total cost of the labour and space resources that the site uses to perform a CABG surgery:

|

|

The TDABC direct cost estimate is the sum of the total labour cost, the total space (including equipment) cost, as well as costs of purchased supplies (ie, acquisition costs for material and medications).

Step 6 includes identification and allocation of the indirect costs attributable to the cycle of care. Indirect costs are those costs that cannot be traced to any particular resource used in the direct care of the patient but are nonetheless essential to be able to provide care. Examples of indirect costs include management salaries, insurance fees and taxes.

The final step of TDABC analysis is the validation of cost estimates with financial and clinical teams from sites, and follow-up refinements to update the costs accordingly.

Data collection

Process and costs

We conducted the TDABC study at three sites and defined CABG surgery as the target medical condition. Process observations and detailed data collection were limited to cardiovascular care departments at each site. Care processes in ancillary departments such as radiology, laboratory and transfusion services, and housekeeping were not observed; instead, we requested each site estimate a cost per patient for those services. Indirect costs were obtained from the sites; however, they were not used to calculate the final cost of CABG in order to standardise our process and to avoid introduction of site-specific assumptions into our comparisons.i

We defined the start of the care delivery cycle as hospital admission and ended the care cycle with hospital discharge. Costs associated with any readmission (even if related to the initial CABG admission) were not included in our TDABC; however, we did capture the CABG readmission and complication rates at each site.

We restricted our study to an ‘average’ (based on relative comorbidities) patient undergoing elective (not emergent), first (no previous CABG or valve surgery), isolated (no other procedures), multivessel CABG. Box 2 displays the criteria used to exclude patients from the study. We studied uncomplicated CABG procedures to allow for valid comparisons across the three sites without the confounding effects of different risk stratification and patient mix variation among the sites.

Box 2. Exclusion criteria.

Concomitant valve surgery or aneurysm removal

Ventricular assist device implantation or removal

Other cardiac procedure

Emergent procedure (including for surgical complication)

Previous coronary artery bypass graft or valve surgery

Previous percutaneous coronary intervention in ≤6h

Mitral insufficiency <21 days

History of cardiogenic shock or cardiopulmonary resuscitation

Preoperative inotrope dependence

Our team visited each hospital to directly observe the CABG procedures and conduct interviews with care providers. During these site visits, the team recorded the following data which were subsequently used to create process maps: (1) all the activities performed over the complete care cycle of CABG, (2) the personnel who performed each activity, (3) the resources consumed in the activity (ie, equipment, space and materials), (4) the length of time each activity required and (5) the probability of occurrence of each activity.

The CABG care cycle can be divided into four phases: preoperative, intraoperative, postoperative (further segmented by postoperative day) and discharge. For each of these phases, a healthcare provider gave us a brief overview of the main steps, which we then observed to document activities in detail, timed either directly and/or using time estimates from interview notes. We attempted to interview at least three individuals in each personnel category, via a pair of interviewers to minimise interviewer bias. For each activity, we interviewed personnel types performing the activity as well as types who would have knowledge of, but not responsibility for, the activity to confirm the accuracy of the original estimates. A copy of the data collection sheet is included in box 3.

Box 3. Fields of the data collection sheet.

Interviewee: personnel type and initials

- For each activity:

- Process (preoperative, intraoperative, etc)

- Detailed description of the activity

- Space

- Personnel types needed for activity

- Probability activity takes place (%)

- Activity time:

- i. Per interviewee (min)

- ii. Per observation (min)

- Discrepancy in activity time between observation and interviews (yes/no):

- i. If yes, frequency of discrepancy

- ii. If yes, causes of discrepancy

During the interview process, the interviewer introduced himself and briefly explained the purpose of the interview. He stated that he was interested in the interviewee's experience with ‘uncomplicated CABG’.ii The interviewer asked about the interviewee's best estimates of the time required to perform each activity for an ‘average’ patient and the probabilities of all activities taking place, as some activities occur for 100% of the patients and others less frequently. The interviewer documented the resources consumed during the activity. The interviewer also asked the provider to estimate how much time they spent with one patient during their whole shift and the provider-to-patient ratio. If the interviewer recognised a discrepancy with prior observations or interviews, he questioned the causes of this discrepancy. In addition, the interviewer asked the interviewee how long each activity would take for a less/more experienced provider.

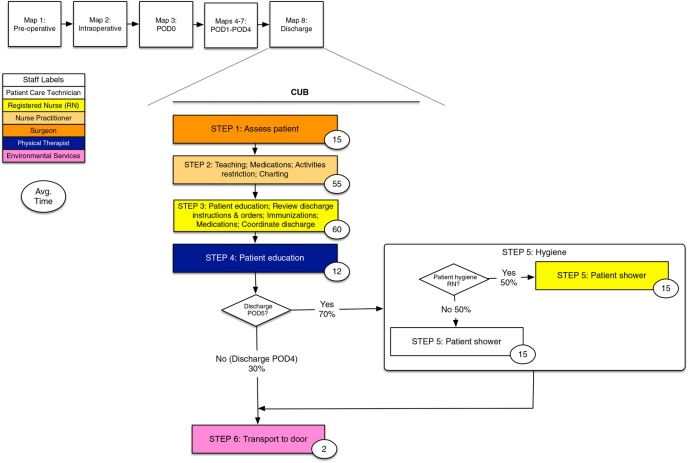

The information from the observations and interviews was then translated into a process map, providing a step-by-step outline of the CABG care pathway. Discrepancies between interviewees, or between observations and interviews, were resolved by further observations and additional interviews with more experienced personnel. Once the process maps were completed (see figure 1 for a sample process map), we validated them with a different set of providers individually or in groups. After returning from the site visits, the team coordinated with each of the sites to collect and verify financial and human resources data.

Figure 1.

Process maps document each activity during the care cycle. For each activity (rectangles), the personnel type assigned to the activity (colour codes), the average time to complete the activity (circles), the probability that the activity takes place (diamonds) and the space where the activity takes place (column) are also documented. CUB, cardiovascular universal bed; PODx, postoperative day x.

Table 1 details the data requested from sites. Although the sites were generally willing and able to share detailed cost data, we assigned numbers based on reasonable assumptions or external sources where data elements were unavailable and verified them with the sites. All cost data received from the site in India were in rupees (INR), so we used the median market exchange rate for the fourth quarter of 2013 (the start date of our site visit to the site in India was 11 November), which was 62INR (rounded) to $1, to convert these costs to US dollars.26 For the same year, the purchasing power parity (PPP) for India was 17INR (rounded) to $1.27 We checked the robustness of our cost calculations using PPP and results were directionally similar. We plan to report cost calculations with both conversion methods.

Table 1.

Requested data. To link these data with the CCRs, we refer the reader to the spreadsheet template presented in the online supplementary appendix

| Personnel | Space | Equipment | Materials |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cost | |||

|

|

|

|

| Capacity | |||

|

|

|

|

*Clinical availability includes direct time available for patients care (such as during clinical shifts) and on-call time, but does not include off-duty, vacation and holiday time, nor does it include time devoted to research, administration and medical education.

†Space and equipment availability includes direct time available for patients care but does not include holiday time, nor does it include maintenance and cleaning time.

Once the data became available, the CCR for each labour and space resource was calculated (as described earlier) and process map steps were then inserted into the financial model template in conjunction with the financial and human resources data collected by the respective site managers at the sites.

Next, we will validate the cost estimates with financial and clinical teams from sites, and will perform follow-up refinements to update the costs if necessary.

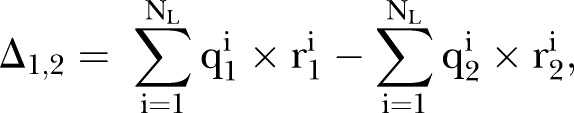

Background on variance analysis

To quantify differences in consumption and pricing of labour resources between the three sites, we will perform a quantitative investigation using variance analysis on labour costs. Variance analysis helps us understand how much of the cost difference between two sites is due to different prices for inputs (personnel, equipment, space) and how much is due to different productivities of resources at the two sites. For example, we can define the total difference in personnel cost between sites 1 and 2 (Δ1,2) as:

|

where  (

( ) is the quantity of personnel type i at site 1 (site 2) and

) is the quantity of personnel type i at site 1 (site 2) and  (

( ) is the price per unit of personnel type i at site 1 (site 2).

) is the price per unit of personnel type i at site 1 (site 2).

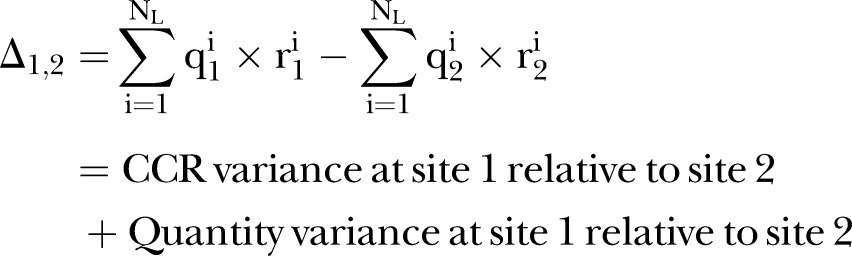

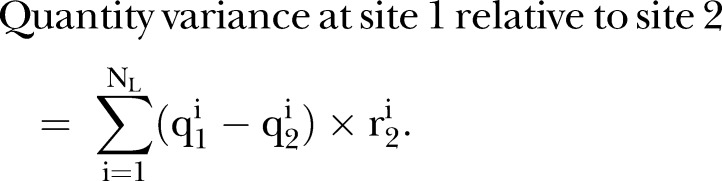

If we designate site 2 as the benchmark site, then the cost difference can be thought of as the cost of site 1 relative to the benchmark site. Furthermore, the cost difference can be split into the sum of two effects: a price or rate variance due to different CCRs of resource i and a quantity variance due to differential use of resource i at the two sites:

|

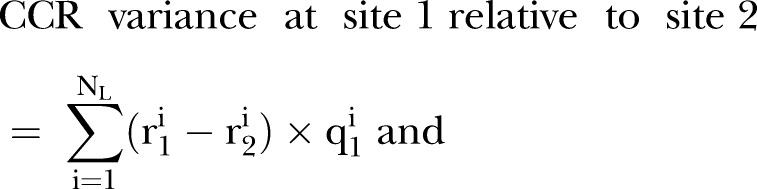

where

|

|

The price (CCR) variance is caused by different CCRs at the two sites; a negative value indicates that site 1 has lower unit resource costs than site 2 and vice versa. The quantity variance (the difference in quantities of inputs) explains cost differences due to different quantities of resources used between the two sites; a negative value indicates that site 1 uses fewer resources than site 2 in performing the CABG surgery, and vice versa. The price variance is due to factors mostly exogenous to health systems, as managers, in the short run, have little ability to modify salaries—which are determined by market conditions—and the capacity of hours worked by personnel, which can be determined by prevailing industry practice and labour union negotiations. Managers, however, can control the quantity variance by improving processes and capacity utilisation. The variance analysis, therefore, enables us to focus on cost differences due to differential productivity at the sites, and avoid the confounding effects of different compensation of comparable personnel and different prices paid for equipment and space. CCR variance and quantity variance will help us quantitatively discern differences between processes of selected sites.

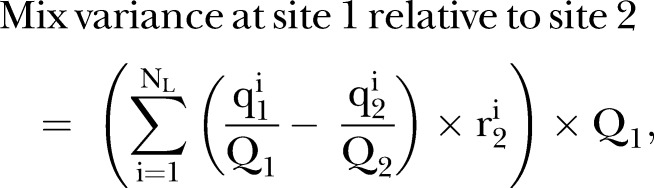

We can further decompose the quantity variance into two factors. The first is the mix variance where the two sites use a different mix of resources. For instance, consider the resource of labour. Site 1 may use relatively more physician time, while site 2 may use relatively more nurse time. This mix variance is measured as follows:

|

where Q1 and Q2 measure the total quantity of labour time used at sites 1 and 2, respectively.

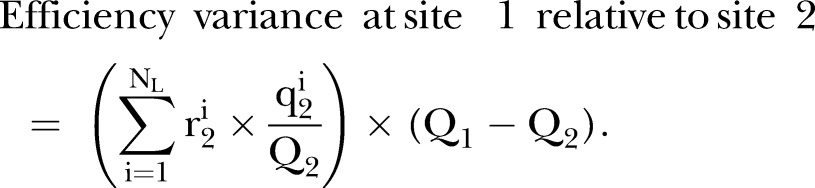

The second is the efficiency variance. This variance measures the cost differences that arise between the two sites because one site uses more of a resource, say labour, than the other. Note, here we are only concerned with differences in total quantity of the resource used rather than the break-up into the different categories of labour such as physician hours or nurse hours.

|

Mix variance and efficiency variance allow us to separate out cost differences due to a different mix of personnel skill used in the care delivery from those due to the quantities of total personnel time used, respectively.

A site can reduce an unfavourable mix variance, for example, by shifting more of the work to lower paid personnel—when it can be done without adverse impact on quality and outcomes—by ensuring that personnel work near or at the ‘top of licence’ or ‘top of capabilities’. It can reduce an unfavourable efficiency variance, for example, by adopting methods used at the more productive site to eliminate non-value added activities in order to reduce the total quantity of employee minutes required to achieve a successful care delivery without having any adverse impact on quality, safety and outcomes.

For example, let us assume that site 1 uses 10 min of surgeon time and 30 min of nurse time to complete a task. Site 2, on the other hand, uses 15 min of surgeon time and 15 min of nurse time for the same task. Let the CCR at site 2 be $2/min for a surgeon and $1/min for a nurse. The quantity variance at site 1 relative to site 2 is $5; that is, it costs $5 more to produce the same task at site 1 ignoring differences in rates. The mix variance is −$10. That is, the cost difference between sites attributable solely to site 1's labour mix that favours more expensive resources is $10 in favour of site 1. However, site 1 uses a lot of labour relative to site 2. This efficiency variance is $15 and it is in favour of site 2. That is, site 1 uses 10 more hours of labour time than site 2 (without regard to the mix of labour used at either site) and this costs site 1 an extra $15. The net effect of these two variances is $5 extra cost at site 1. Recall that this difference is purely on account of quantity variance and ignores any differences in rates per hour across the two sites (which is captured in the rate variance calculations).

Dissemination

Results will be published in peer-reviewed journals and presented at national and international scientific meetings.

Discussion

TDABC, using CCRs for resource inputs (labour and non-labour) combined with detailed process maps, will allow for granular comparison of the cost of producing CABG across multiple sites. The use of variance analysis across the three sites will enable us to understand intersite differences. We will identify the differences, if any, in care delivery between the selected sites. We hypothesise that understanding the sources of cost variation across the three sites may reveal opportunities for cost reduction which does not jeopardise patient outcomes. Such an analysis can also identify best practices in efficient CABG production.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Maziyar Kalani, MD; Christine Nguyen, MD, MS; Kimberly Brayton, MD, JD, MS; Mary Carol Mazza, PhD; and Rajbinder Mann for their help with interviews.

Footnotes

Collaborators: Maziyar Kalani, Christine Nguyen, Kimberly Brayton, Mary Carol Mazza, Rajbinder Mann.

Contributors: AM initially proposed the study. RSK and VGN specified the methodology. All authors contributed to the protocol design and analysis plan. FE wrote the initial manuscript, and all authors contributed to improving the manuscript. All authors approved the final manuscript.

Funding: The study was supported by the Sue and Dick Levy Fund, an advised fund of the Silicon Valley Community Foundation.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: All methods were exempted from review by the Stanford Institutional Review Board.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

We chose this approach because assigning these costs accurately would require extending the scope of the TDABC analysis on all these categories of expenses, which would necessitate a great deal of time and effort.

During the interviews, the interviewers returned back to this concept several times and when there was any uncertainty in terms of what this concept was, re-explained it to the interviewees. After the interviews, we compared the process maps to make sure that they did not reflect activity associated with complications or other patient characteristics that differed from the clinical frame of reference that we wanted them to use.

References

- 1.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. National health expenditures 2013 highlights. Baltimore, MD, 2014. http://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/downloads/highlights.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartman M, Martin AB, Lassman D et al. National health spending in 2013: growth slows, remains in step with the overall economy. Health Aff 2014;34:150–60. 10.1377/hlthaff.2014.1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Delaune J, Everett W. Waste and inefficiency in the U.S. health care system. Cambridge, MA, 2008. http://www.nehi.net/writable/publication_files/file/waste_clinical_care_report_final.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 4.Smith M, Saunders R, Stuckhardt L et al. Best care at lower cost: the path to continuously learning health care in America. Washington DC, 2013. http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2012/Best-Care-at-Lower-Cost-The-Path-to-Continuously-Learning-Health-Care-in-America.aspx (accessed 14 Dec 2014). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Roger VL, Go AS, Lloyd-Jones DM et al. Executive summary: heart disease and stroke statistics—2012 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2012;125:188–97. 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182456d46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mozaffarian D, Benjamin EJ, Go AS et al. Executive summary: heart disease and stroke statistics—2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2015;131:434–41. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Govindarajan V, Ramamurti R. Delivering world-class health care, affordably. Harv Bus Rev 2013;91:117–22.23451530 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kaplan RS, Porter ME. How to solve the cost crisis in health care. Harv Bus Rev 2011;89:46–52, 54, 56–61 passim. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kaylin A.2013. Why does health care cost so much? Hospitals don't know what their costs are. https://www.aseonline.org/ArticleDetailsPage/tabid/7442/ArticleID/586/Why-Does-Health-Care-Cost-so-Much-Hospitals-Don't-Know-What-Their-Costs-Are.aspx.

- 10.Brown PP, Kugelmass AD, Cohen DJ et al. The frequency and cost of complications associated with coronary artery bypass grafting surgery: results from the United States Medicare program. Ann Thorac Surg 2008;85:1980–6. 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.01.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Baker JJ. Activity-based costing and activity-based management for health care. Gaithersburg, Maryland: Aspen Publishers, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lievens Y, van den Bogaert W, Kesteloot K. Activity-based costing: a practical model for cost calculation in radiotherapy. Int J Radiat Oncol 2003;57:522–35. 10.1016/S0360-3016(03)00579-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Capettini R, Chow CW, McNamee AH. On the need and opportunities for improving costing and cost management in healthcare organizations. Manag Financ 1998;24:46–59. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dugel PU, Tong KB. Development of an activity-based costing model to evaluate physician office practice profitability. Ophthalmology 2011;118:203–8.e1–3. 10.1016/j.ophtha.2010.04.035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shander A, Hofmann A, Ozawa S et al. Activity-based costs of blood transfusions in surgical patients at four hospitals. Transfusion 2010;50:753–65. 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02518.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaplan RS, Anderson SR. Time-driven activity-based costing. Harv Bus Rev 2004;82:131–8, 150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaplan RS, Anderson SR. The innovation of time-driven activity-based costing. J Cost Manag 2007;21:5–15. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Demeere N, Stouthuysen K, Roodhooft F. Time-driven activity-based costing in an outpatient clinic environment: development, relevance and managerial impact. Health Policy 2009;92:296–304. 10.1016/j.healthpol.2009.05.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Öker F, Özyapıcı H. A new costing model in hospital management: time-driven activity-based costing system. Health Care Manag (Frederick) 2013;32:23–36. 10.1097/HCM.0b013e31827ed898 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kaplan RS, Witkowski M, Abbot M et al. Using time-driven activity-based costing to identify value improvement opportunities in healthcare. J Healthc Manag 2014;59:399–412. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kaplan AL, Agarwal N, Setlur NP et al. Measuring the cost of care in benign prostatic hyperplasia using time-driven activity-based costing (TDABC). Healthcare (Amst) 2015;3:43–8. 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2014.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akhavan S, Ward L, Bozic KJ. Time-driven activity-based costing more accurately reflects costs in arthroplasty surgery. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2015. [Epub ahead of print 27 Feb 2015]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.French KE, Albright HW, Frenzel JC et al. Measuring the value of process improvement initiatives in a preoperative assessment center using time-driven activity-based costing. Healthcare 2013;1:136–42. 10.1016/j.hjdsi.2013.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.About The Joint Commission | Joint Commission. http://www.jointcommission.org/about_us/about_the_joint_commission_main.aspx (accessed 17 Dec 2014).

- 25.Who is JCI—Who We Are | Joint Commission International. http://www.jointcommissioninternational.org/about-jci/who-is-jci/ (accessed 17 Dec 2014).

- 26.USD to INR Conversion Chart—Bloomberg. http://www.bloomberg.com/quote/USDINR:CUR/chart (accessed 17 Dec 2014).

- 27.The International Comparison Program (ICP). http://siteresources.worldbank.org/ICPEXT/Resources/ICP_2011.html (accessed 17 Dec 2014).