Abstract

Objectives

This study explores the relationship between alcohol consumption, health, ethnicity and socioeconomic deprivation.

Participants

27 991 people aged 65 and over from an inner-city population, using a primary care database.

Primary and Secondary Outcome Measures

Primary outcome measures were alcohol use and misuse (>21 units per week for men and >14 for units per week women).

Results

Older people of black and minority ethnic (BME) origin from four distinct ethnic groups comprised 29% of the sample. A total of 9248 older drinkers were identified, of whom 1980 (21.4%) drank above safe limits. Compared with older drinkers, older unsafe drinkers contained a higher proportion of males, white and Irish ethnic groups and a lower proportion of Caribbean, African and Asian groups. For older drinkers, the strongest independent predictors of higher alcohol consumption were younger age, male gender and Irish ethnicity. Independent predictors of lower alcohol consumption were Asian, black Caribbean and black African ethnicity. Socioeconomic deprivation and comorbidity were not significant predictors of alcohol consumption in older drinkers. For older unsafe drinkers, the strongest predictor variables were younger age, male gender and Irish ethnicity; comorbidity was not a significant predictor. Lower socioeconomic deprivation was a significant predictor of unsafe consumption whereas African, Caribbean and Asian ethnicity were not.

Conclusions

Although under-reporting in high-alcohol consumption groups and poor health in older people who have stopped or controlled their drinking may have limited the interpretation of our results, we suggest that closer attention is paid to ‘young older’ male drinkers, as well as to older drinkers born outside the UK and those with lower levels of socioeconomic deprivation who are drinking above safe limits.

Keywords: MENTAL HEALTH, PUBLIC HEALTH, PRIMARY CARE

Strengths and limitations of this study.

To our knowledge, the first published UK study examining the impact of socioeconomic deprivation, ethnicity and comorbidity on alcohol use in older people, based on primary care data.

The database contains an almost complete population sample of older people within a geographically defined inner-city area.

Sample not representative of the UK population, containing lower proportion of people aged 65 and over and higher population of people with Irish ethnicity than the UK population.

Under-reporting may have been present when alcohol consumption recorded.

Difficult to extrapolate the findings from an inner-city population to other geographical areas.

Introduction

The clinical and public health aspects of alcohol use and misuse in older people have been brought sharply into focus over the past few years, with the recognition of a growing burden of morbidity and mortality that includes drinking above recommended limits, alcohol-related hospital admissions, alcohol-related deaths and the presence of accompanying mental disorders or ‘dual diagnosis’ in alcohol misuse.1–3Concerns have also been raised that current recommendations on safe drinking limits are set too high for older age groups.4

In the UK, older people from some black and minority ethnic backgrounds have higher levels of alcohol misuse than the general older population, with Irish and south Asian (Sikh) male migrants to the UK being at particular risk.5 In certain areas of the UK, the combination of Irish ethnicity and social marginalisation is known to be associated with high rates of alcohol misuse.6 A combination of ‘Irish’ (greater number of drinks per drinking session) and ‘English’ (greater number of days engaged in drinking) drinking patterns may be responsible for the greater risk of harmful drinking.7 This is further compounded by negative stereotyping and low rates of primary care consultation in the Irish population.8 These factors may influence access to alcohol services.

The relationship between socioeconomic deprivation and alcohol misuse in older people is more complex, particularly when factors such as previous occupation are taken into account.9 Higher socioeconomic status is known to be associated with higher alcohol consumption in older people, with income showing a positive association with moderate and heavy drinking.10–13

There has been a dearth of literature examining alcohol misuse and its relationship with socioeconomic and health status in older UK populations. The only published study in people aged 65 years and over exploring the relationship between alcohol consumption, socioeconomic status and health involved a sample population aged 75 and over.

In this study, drinking above recommended limits of 21 units (168 g of pure ethanol) for men and 14 units (112 g of pure ethanol) for women was associated with greater anxiety and with tobacco smoking compared with non-drinkers and those drinking within recommended limits.

Independent variables predicting this drinking pattern were being male, having a reduced risk of both myocardial infarction and diabetes mellitus, as well as a higher rating of self-reported health status and being a home owner (as a proxy measure of socioeconomic status).14 However, an under-estimation of cardiovascular burden in those drinking above recommended limits coupled with an over-representation of cardiovascular disease in those who have reduced their intake following ill-health (so-called ‘sick quitters’) are likely to have influenced the findings. The study did not provide details of non-responders, which may have also influenced the validity of the results.

The current study examines the association between alcohol consumption, ethnicity, socioeconomic deprivation and health in an inner-city cohort of people aged 65 years and over using a patient-level, primary care database from general practices in south east London, UK.

Method

Data source

We obtained data from Lambeth DataNet, an anonymised data set consisting of anonymised Read-coded clinical data derived from general practices in Lambeth, in inner London.15 The data set contains clinical data from all patients registered at practices contributing data to Lambeth DataNet. Data were extracted in October 2013 at which time 366 323 patients were registered at the 49 out of 50 practices participating in Lambeth DataNet; the remaining practice had an incompatible clinical software system. Socioeconomic deprivation was measured using the Index of Multiple Deprivation 2010 (McLennan et al 2011). This compares areas of similar population size, each termed a Lower layer Super Output Area (LSOA). The Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) index within these LSOAs is made up of seven LSOA level domain indices. These relate to income deprivation, employment deprivation, health deprivation and disability, education skills and training deprivation, barriers to housing and services, living environment deprivation and crime.16

Study sample

We confined our analysis to those aged 65 years and over, producing a sample of 27 991 patients (7.6% of the registered population).

Data analysis

In order to determine the association between alcohol consumption and the demographic and clinical variables, we constructed a series of regression models. The outcome variable was the volume of alcohol consumption (units per week). Predictor variables included age, gender, ethnicity and specified comorbidities.

Comorbidity consisted of all long-term conditions which are part of the Quality and Outcomes Framework (Department of Health, 2003),17 including hypertension, respiratory disease, heart disease, chronic kidney disease, stroke, cancer, thyroid disease, dementia and depression. Regression analyses were carried for all older people coded as drinking any alcohol. Given that drinking above safe limits is known to be associated with alcohol-related harm, the regression analysis was repeated for older men and women drinking above safe limits (>21 units for men and >14 for women).

Standardised β coefficients were used in data interpretation for regression analyses. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS V.22. The β value in this study is a measure of how strongly each predictor variable influenced alcohol consumption.

Results

The age, sex and ethnicity of the whole population and those aged 65 years and over are displayed in table 1. Twenty per cent of ethnicity data was missing for the whole sample and 14% missing for the group aged 65 years and over. The remaining breakdown of ethnicity (where available) is shown in table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic features of patients

| Whole sample | Aged 65 years and over | |

|---|---|---|

| Number | 366 322 | 27 991 |

| Mean (SD) age | 35.5 (18.8) | 74.7 (7.6) |

| Sex | 51.1% Male | 46% Male |

| 48.9% Female | 54% Female | |

| Ethnicity | 57.6% white | 59.1% white |

| 2.1% Irish | 5.0% Irish | |

| 12.2% Caribbean | 15.2% Caribbean | |

| 8.9% African | 7.1% African | |

| 6.1% Asian | 6.6% Asian |

‘Older drinkers’ drinking any amount of alcohol (1 unit and above) and ‘Unsafe drinkers’ drinking over recommended limits (>21 units for men and >14 for women) are detailed in table 2, by age, sex and ethnicity for the older population. Missing ethnicity data accounted for 10.6% of older people drinking any alcohol and 14.4% for older people drinking over recommended limits. As in table 1, a further breakdown of ethnicity is shown, where this was available. Compared with the sample of older drinkers, unsafe drinkers contained a higher proportion of males, white and Irish ethnic groups; as well as a lower proportion of Caribbean, African and Asian groups.

Predictors of alcohol consumption in older people

Age, gender, ethnicity, comorbidity and deprivation score accounted for 31.1% of the variance in alcohol consumption in older drinkers (table 3).

Table 3.

Predictors of alcohol consumption in older people

| Standardised β coefficient | Significance | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | −0.24 | <0.001 |

| Age | −0.13 | <0.001 |

| IMD score | −0.01 | 0.32 |

| Ethnicity (Caribbean) | −0.01 | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity (African) | −0.06 | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity (Irish) | 0.06 | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity (Asian) | −0.01 | <0.001 |

| Any comorbidity | −0.01 | 0.51 |

IMD, Index of Multiple Deprivation.

Table 2.

Demographic features of patients aged 65 and over drinking alcohol

| Older drinkers | Unsafe drinkers | |

|---|---|---|

| Number | 9248 | 1980 |

| Mean (SD) age | 73.7 (7.1) | 72.1 (6.3) |

| Sex | 60% Male | 65.1% Male |

| 40% Female | 34.9% Female | |

| Ethnicity | 67.9% white | 79.8% white |

| 6.2% Irish | 8.2% Irish | |

| 13.3% Caribbean | 6.5% Caribbean | |

| 4.% African | 1% African | |

| 3.7% Asian | 2.5% Asian |

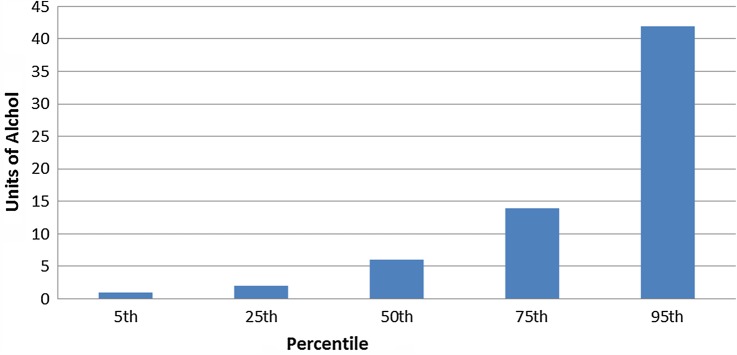

The median volume of alcohol consumed by the older drinkers was 6 units per week (figure 1). For males, the highest 5th centile were drinking ≥50 units per week and for females, ≥23 U per week. Altogether, 1980 (21.4%) of the older drinkers exceeded recommended (safe) limits.

Figure 1.

Alcohol consumption in older drinkers.

The strongest independent predictors of higher alcohol consumption were younger age, male gender and Irish ethnicity. Independent predictors of lower alcohol consumption were Asian, black Caribbean and black African ethnicity. However, socioeconomic deprivation and comorbidity were not significant predictors of alcohol consumption.

Predictors of alcohol consumption in older unsafe drinkers

We repeated our regression analysis (table 4) in those who drank above the safe limits of alcohol (n=1980). This model predicted 41.6% of the variance in alcohol consumption.

Table 4.

Predictors of alcohol consumption in older unsafe drinkers

| Standardised β coefficient | Significance | |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | −0.36 | <0.001 |

| Age | −0.11 | <0.001 |

| IMD score | −0.07 | 0.003 |

| Ethnicity (Caribbean) | 0.03 | 0.13 |

| Ethnicity (African) | −0.03 | 0.23 |

| Ethnicity (Irish) | 0.08 | <0.001 |

| Ethnicity (Asian) | −0.04 | 0.09 |

| Any comorbidity | −0.01 | 0.84 |

IMD, Index of Multiple Deprivation.

As in the previous model, the three strongest predictor variables were younger age, male gender and Irish ethnicity; comorbidity was not a significant predictor. Unlike the previous model, a lower level of socioeconomic deprivation was a significant predictor of ‘unsafe’ consumption whereas African, Caribbean and Asian ethnicity were not significant predictors.

Discussion

We found clear associations between alcohol consumption and age, gender and ethnicity in our older drinkers, as well as between unsafe drinking and age, gender and socioeconomic deprivation.

To our knowledge, this is the first published UK study examining the impact of socioeconomic deprivation, ethnicity and comorbidity on alcohol use in older people, based on primary care data. Uniquely, the database contains an almost complete population sample of older people within a geographically defined inner-city area.

Our inner-city older population was not representative of the UK population. It contained a comparatively lower proportion of people aged 65 and over (7.6%) compared with 16% of the UK population.18 Conversely, the population of people of Irish ethnicity in our group aged 65 and over was 5%, as compared with 1.7% of the UK population.18

In our cohort of older patients, those closer to the age of 65 were more likely to drink and more likely to be unsafe drinkers than more elderly patients. This is consistent with previous community-based studies of drinking in older people.19–21 13 A similar observation has been noted for increased alcohol use in men as compared to women in the same studies.19–21 13

The relationship between alcohol consumption and socioeconomic status has started to receive increased attention over the past decade, with some consistency in the observation that older people are more likely to drink more if they have less socioeconomic deprivation.20–22

In the current study, deprivation scores did not predict alcohol intake in the group drinking alcohol, but lower deprivation did predict higher alcohol use in those older people drinking above safe limits. This may be surprising in an inner-city population, given that environmental factors such as not going out of the home and a change in social circumstances have been found to predict unhealthy drinking behaviour in older people.23 Similarly, living alone has been shown to increase hazardous alcohol use in an older age group.24

Our study found no association between comorbidity across a range of physical and mental disorders. It is possible that it was confounded by problems found from other studies such as under-reporting and the presence of ‘sick quitters’. There is conflicting evidence for an association between alcohol misuse and depression,24–26 as well as with physical health status.20 23–25

Recording of functional activity scores was poorly recorded in our data set. We were unable to include data covering activities of daily living, although the association between alcohol intake and functional impairment in older people has produced similarly conflicting findings.26–30

Our observation that the top 5% of men and women drinking any alcohol were drinking more than 49 units and more than 23 units per week, respectively, is in line with very similar findings from national data on drinking patterns for older people in England28 However, over 21% of all older people in our study who drank any alcohol did so above safe limits. This is more than that of both men and women in the general population, which is 20% and 9% respectively.29 The reason for this remains unclear, but may be attributable to an older population of Irish ethnicity whose proportion is three times higher than the UK population.

There are several limitations to this study. Missing ethnicity was higher in unsafe drinkers than older drinkers, which may have influenced our findings. We did not have a breakdown of ethnicity data within African and Asian groups. Selection bias from under-reporting is also known to occur in studies that explore substance use in older people,30–32 given the stigma associated with drinking. It is also difficult to extrapolate the findings from an inner-city population to other geographical areas.

Although further separation of drinking limits would make the analysis and interpretation of the study less robust, the possibility of residual confounding within narrower age bands needs to be considered.

Addressing the risk factors for alcohol use and misuse in older people is paramount to improving the health and social outcomes, as well as reducing the public health burden associated with unhealthy alcohol use in older people.

Alcohol-related harm contributes to between 3% and 5% of global deaths and disability-adjusted life-years worldwide, as well as amounting to more than 1% of the gross domestic product in high-income and middle-income countries.33

This harm is strongly related to alcohol intake, with a stronger association in poor people and in those who are marginalised from society. In the UK, the contributions of cirrhosis to premature mortality rose from 1990 to 2010.34

There is considerable scope for reducing alcohol-related harm, particularly through regulating access to alcohol consumption from increasing price and reducing availability.35

Although the exact definition of unhealthy use continues to be debated,36 37 the impact of alcohol misuse in older populations continues to weigh heavy on clinical services38 39

The effect of higher levels of alcohol misuse in the ‘baby boomer’ cohort than in younger age groups has particular relevance to the current study.40 Our findings suggest that close attention needs to be paid to identifying alcohol misuse in ‘young older’ men, paying close attention to the needs of those born outside the UK41 42 and those living in areas of lower deprivation.

As such, these findings will have implications for informing policy, commissioning services, training in detection and treatment, together with integrated care for older people at greatest risk for alcohol misuse.

Footnotes

Twitter: Follow Rahul Rao at @kentjrchess

Contributors: RR and MA made substantial contributions to the design, analysis and interpretation of data for the work. PS made a substantial contributions to the analysis and interpretation of data for the work. RR, MA and PS made substantial contributions to revising it critically for important intellectual content; giving final approval of the version to be published and all agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Crome I, Brown A, Dar K et al. Our invisible addicts: first report of the older persons’ substance misuse Working Group of the Royal College of Psychiatrists. London: Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rao RT. Older people and dual diagnosis–out of sight, but not out of mind. Adv Dual Diagn 2011;4:1. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rao R, Shanks A. Development and implementation of a dual diagnosis strategy for older people in south east London. Adv Dual Diagn 2011;4:28–35. 10.1108/17570971111155595 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knott C, Scholes S, Shelton N. PS51 Could more than three million older people be at risk of alcohol-related harm? A cross-sectional analysis of age-specific drinking guidelines. J Epidemiol Community Health 2012;66(Suppl 1):A58 10.1136/jech-2012-201753.150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rao R. Alcohol misuse and ethnicity. BMJ 2006;332:682 10.1136/bmj.332.7543.682 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rao R, Wolff K, Marshall E. Alcohol use and misuse in older people: a local prevalence study comparing English and Irish inner-city residents living in the UK. J Subst Use 2008;13:17–26. 10.1080/14659890701639824 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McCambridge J, Conlon P, Keaney F et al. Patterns of alcohol consumption and problems among the Irish in London: a preliminary comparison of pub drinkers in London and Dublin. Addict Res Theory 2004;12:373–84. 10.1080/16066350410001713222 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramstedt M, Hope A. The Irish drinking habits of 2002-drinking and drinking-related harm in a European comparative perspective. J Subst Use 2005;10:273–83. 10.1080/14659890412331319443 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anderson P. Alcohol and the workplace. Barcelona: Department of Health (Government of Barcelona), 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bonevski B, Regan T, Paul C et al. Associations between alcohol, smoking, socioeconomic status and comorbidities: evidence from the 45 and Up Study. Drug Alcohol Rev 2014;33:169–76. 10.1111/dar.12104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Touvier M, Druesne-Pecollo N, Kesse-Guyot E et al. Demographic, socioeconomic, disease history, dietary and lifestyle cancer risk factors associated with alcohol consumption. Int J Cancer 2014;134:445–59. 10.1002/ijc.28365 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wagner GA, Lebrão ML, Duarte YA et al. Alcohol use among older adults: SABE cohort study, São Paulo, Brazil. PLoS ONE 2014;9:e85548 10.1371/journal.pone.0085548 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Merrick EL, Horgan CM, Hodgkin D et al. Unhealthy drinking patterns in older adults: prevalence and associated characteristics. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:214–23. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01539.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hajat S, Haines A, Bulpitt C et al. Patterns and determinants of alcohol consumption in people aged 75 years and older: results from the MRC trial of assessment and management of older people in the community. Age Ageing 2004;33:170–7. 10.1093/ageing/afh046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Department of Health. Investing in general practice: the new general medical services contract. London: Department of Health, 2003. http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance [Google Scholar]

- 16.McLennan D, Barnes H, Noble M et al. The English indices of deprivation 2010. London: Department for Communities and Local Government, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kumarapeli P, Stepaniuk R, de Lusignan S et al. Ethnicity recording in general practice computer systems. J Public Health 2006;28:283–7. 10.1093/pubmed/fdl044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Centre on Dynamics of Ethnicity (CoDE). ‘Dynamics of diversity: evidence from the 2011 Census’. University of Manchester, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Immonen S, Valvanne J, Pitkala KH. Prevalence of at-risk drinking among older adults and associated sociodemographic and health-related factors. J Nutr Health Aging 2000;15:789–94. 10.1007/s12603-011-0115-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Weyerer S, Schäufele M, Eifflaender-Gorfer S et al. , German AgeCoDe Study groupFurther members of the German AgeCoDe Study group.-Heinz-Harald Abholz, Cadja Bachmann, Wolfgang Blank, Michaela Buchwald, Mirjam Colditz, Moritz Daerr, Frank Jessen, Sven Heinrich, Hanna Kaduszkiewicz, Teresa Kaufeler, Hans-Helmut König, Tobias Luck, Melanie Luppa, Manfred Mayer, Julia Olbrich, Heinz-Peter Romberg, Anja Rudolph, Melanie Sauder, Britta Schürmann, Michael Wagner, Jochen Werle, Anja Wollny. (German Study on Ageing, Cognition, Dementia in. At-risk alcohol drinking in primary care patients aged 75 years and older. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry 2009;24:1376–85. 10.1002/gps.2274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Borok J, Galier P, Dinolfo M et al. Why do older unhealthy drinkers decide to make changes or not in their alcohol consumption? Data from the Healthy Living as You Age Study. J Am Geriatr Soc 2013;61:1296–302. 10.1111/jgs.12394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kharicha K, Iliffe S, Harari D et al. Health risk appraisal in older people 1: are older people living alone an ‘at-risk'group? Br J Gen Pract 2007;57:271–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoeck S, Van Hal G. Unhealthy drinking in the Belgian elderly population: prevalence and associated characteristics. Eur J Public Health 2013;23:1069–75. 10.1093/eurpub/cks152 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Walters K, Breeze E, Wilkinson P. Local area deprivation and urban–rural differences in anxiety and depression among people older than 75 years in Britain. Am J Public Health 2004;94:1768–74. 10.2105/AJPH.94.10.1768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kirchner JE, Zubritsky C, Cody M et al. Alcohol consumption among older adults in primary care. J Gen Intern Med 2007;22:92–7. 10.1007/s11606-006-0017-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Friedmann PD, Jin L, Karrison T et al. The effect of alcohol abuse on the health status of older adults seen in the emergency department. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse 1999;25:529–42. 10.1081/ADA-100101877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reid MC, Boutros NN, O'Connor PG et al. The health-related effects of alcohol use in older persons: a systematic review. Subst Abus 2002;23:149–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guralnik JM, Kaplan GA. Predictors of healthy aging: prospective evidence from the Alameda County study. Am J Public Health 1989;79:703–8. 10.2105/AJPH.79.6.703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lang I, Guralnik J, Wallace RB et al. What level of alcohol consumption is hazardous for older people? Functioning and mortality in US and English national cohorts. J Am Geriatr Soc 2007;55:49–57. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.01007.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.NHS Information Centre. Statistics on alcohol. London, England: Health and Social Care Information Centre, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rockett IR, Putnam SL, Jia H et al. Declared and undeclared substanceuse among emergency department patients: a population-based study. Addiction 2006;101:706–12. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01397.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Drennan V, Walters K, Lenihan P et al. Priorities in identifying unmet need in older people attending general practice: a nominal group technique study. Fam Pract 2007;24:454–60. 10.1093/fampra/cmm034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rehm J, Mathers C, Popova S et al. Global burden of disease and injury and economic cost attributable to alcohol use and alcohol-use disorders. Lancet 2009;373:2223–33. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60746-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Anderson P, Chisholm D, Fuhr DC. Effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of policies and programmes to reduce the harm caused by alcohol. Lancet 2009;373:2234–46. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60744-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Murray C, Richards MA, Newton JN et al. UK health performance: findings of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 2013;381:997–1020. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60355-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Crome I, LI T, Rao R et al. Alcohol limits in older people. Addiction 2012;107:1541–3. 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.03854.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Crome IB, Crome P, Rao R. Addiction and ageing–awareness, assessment and action. Age Ageing 2011;40:657–8. 10.1093/ageing/afr129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rao R. Outcomes from liaison psychiatry referrals for older people with alcohol use disorders in the UK. Ment Health Subst Use 2013;6:362–8. 10.1080/17523281.2012.754785 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Davies SC. Annual Report of the Chief Medical Officer, Surveillance Volume, 2012: On the State of the Public's Health. London: Department of Health, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rao R, Crome I, Crome B, et al Substance Misuse in Older People: an Information Guide. Cross Faculty Report FR/OA/A)/01. London: The Royal College of Psychiatrists, 2015. http://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/pdf/Substance%20misuse%20in%20Older%20People_an%20information%20guide.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bhala N, Bhopal R, Brock A et al. Alcohol-related and hepatocellular cancer deaths by country of birth in England and Wales: analysis of mortality and census data. J Public Health 2009;31:250–7. 10.1093/pubmed/fdp014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bhala N, Fischbacher C, Bhopal R. Mortality for alcohol-related harm by country of birth in Scotland, 2000–2004: potential lessons for prevention. Alc Alcohol 2010;45:552–6. 10.1093/alcalc/agq056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]