Abstract

Objectives

To assess the association between being overweight or obese with low back pain (LBP) and clinically defined low back disorders across the life course.

Design

A longitudinal and cross-sectional study.

Setting

A nationwide health survey supplemented with data from records of prior compulsory military service.

Participants

Premilitary health records (baseline) were searched for men aged 30–50 years (n=1385) who participated in a national health examination survey (follow-up).

Methods and outcome measures

Height and weight were measured at baseline and follow-up, and waist circumference at follow-up. Weight at the ages of 20, 30, 40 and 50 years were ascertained, when applicable. Repeated measures of weight were used to calculate age-standardised mean body mass index (BMI) across the life course. The symptom-based outcome measures at follow-up included prevalence of non-specific and radiating LBP during the previous 30 days. The clinically defined outcome measures included chronic low back syndrome and sciatica.

Results

Baseline BMI (20 years) predicted radiating LBP in adulthood, with the prevalence ratio (PR) being 1.26 (95% CI 1.08 to 1.46) for one SD (3.0 kg/m2) increase in BMI. Life course BMI was associated with radiating LBP (PR=1.23; 95% CI 1.03 to 1.48 per 1 unit increment in Z score, corresponding to 2.9 kg/m2). The development of obesity during follow-up increased the risk of radiating LBP (PR=1.91, 95% CI 1.03 to 3.53). Both general and abdominal obesity (defined as waist-to-height ratio) were associated with radiating LBP (OR=1.64, 95% CI 1.02 to 2.65 and 1.44, 95% CI 1.02 to 2.04). No associations were seen for non-specific LBP.

Conclusions

Our findings imply that being overweight or obese in early adulthood as well as during the life course increases the risk of radiating but not non-specific LBP among men. Taking into account the current global obesity epidemic, emphasis should be placed on preventive measures starting at youth and, also, measures for preventing further weight gain during the life course should be implemented.

Keywords: EPIDEMIOLOGY

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This study used a longitudinal design with a random population sample combining data from compulsory military service with a later health examination.

The low back outcomes included self-reported symptoms as well as clinically defined disorders.

We used both general and abdominal obesity as weight-related indicators.

The availability of multiple measures of weight across the life course enabled us to account for the temporal fluctuation of weight over time and allowed exploration of the associations of early indicators of obesity, change in obesity status over time, as well as life course BMI, with the outcomes.

Part of the weight-related measures during the life course was self-reported, and therefore recall bias may have affected the observed associations. The military records did not provide measures of abdominal adiposity at baseline, therefore we were not able to explore the associations of abdominal obesity across the life course.

Introduction

Low back disorders are the most prevalent musculoskeletal health concerns in populations and may cause varying degrees of disability.1 Obesity is another common public health problem that continues to increase.2 3 The increase has been especially pronounced in children and adolescents.4 5

Two recent meta-analyses showed that overweight and obesity increase the risk of both low back pain (LBP) and lumbar radicular pain.6 7 For LBP, the associations have been stronger in women compared with men,8–11 however, for lumbar radicular pain, no gender difference has been found.

Nearly all studies have looked at the effects of general obesity defined by body mass index (BMI). The use of BMI has been criticised for its inability to distinguish the difference between fat and lean mass, especially in men.12 13 Abdominal obesity defined by waist circumference has been associated with LBP in women, but not in men.8 14 15

Most previous studies on the influence of obesity on low back symptoms have been cross-sectional and the majority of prospective studies have had a relatively short follow-up time. Repeated measurements of weight-related factors have rarely been carried out, especially in young populations.8 16 To the best of our knowledge, there are no studies evaluating the lifetime burden of overweight and obesity on low back outcomes.

The aim of this study was to assess the association of overweight and obesity with LBP and clinically defined low back disorders across the life course. In a longitudinal approach, we wanted to find out whether high BMI at the age of 20 years or during the life course predicts increased risk of low back disorders later in life. Moreover, we looked at whether changes in BMI during follow-up affect the risk of LBP. Finally, we explored the cross-sectional associations of general and abdominal obesity with the outcomes.

Materials and methods

Study population

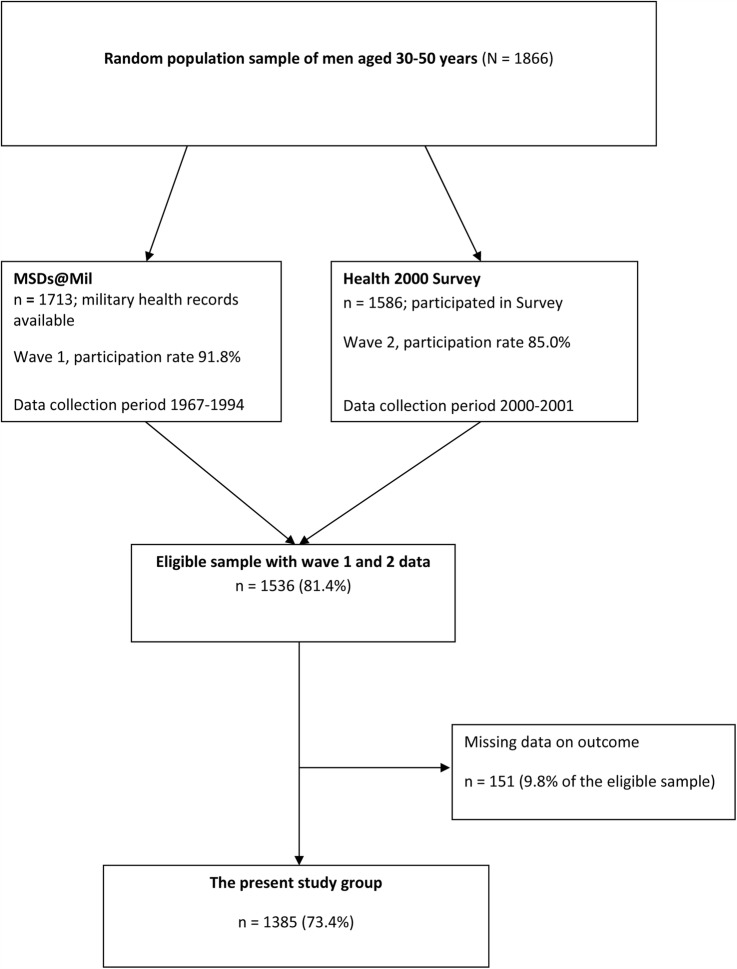

The current study used a longitudinal design with two waves of data collection (figure 1). A random sample of the nationally representative Health 2000 Study (carried out during 2000–2001), comprising of 1866 men aged 30–50 years, formed our study base. The main purposes and methods of this study have been described in detail elsewhere.17 18 Participants for the first wave of our data collection (baseline: Musculoskeletal Disorders in Military Service Study, MSDs@Mil Study) comprised of the 1713 (91.8%) men eligible for military service during 1967–1994 whose military records were found from the register of the Finnish Defence Forces. Of the random sample, 1586 (85.0%) men participated in the second wave of data collection (the Health 2000 Study, follow-up). A total of 1536 men (81.4% of the initial random sample) participated in both waves and formed the eligible sample for the current study.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of the formation of the present study sample (MSDs@Mil Study, Musculoskeletal Disorders in Military Service Study).

Men who did not participate in the Health 2000 Study were slightly younger, belonged more frequently to the Swedish speaking minority and more often had severe mental problems than those who participated. Differences in education and socioeconomic status were minor.17 Furthermore, there was no difference in baseline BMI between participants and non-participants of the Health 2000 Study.

We excluded participants with missing data on LBP at follow-up (n=151, 9.8% of the eligible sample) resulting in a total of 1385 (74.2% of the initial random sample) participants available for the analyses.

Low back outcomes at follow-up

All the men underwent a symptom interview and a comprehensive health examination (including a physical examination performed by a specially trained physician) or a condensed health examination at home. The symptom-based outcome measures included prevalence of LBP (non-specific LBP) and radiating LBP during the previous 30 days. The information on LBP was collected by the following questions: ‘Have you ever had low back pain? (yes/no)’. Those who answered yes were asked about recent pain and about the type of pain: ‘Have you had low back pain during the preceding 30 days? (yes/no)’; ‘If you had low back pain, did it radiate? (0=no, 1=below knee, 2=above knee)’. Radiating LBP was defined as pain that radiated either below or above the knee. The clinically defined outcome measures included chronic low back syndrome and sciatica diagnosed with predefined criteria by specially trained physicians.19 20 The diagnoses made by the physicians were based on previous and current symptoms, documentation on previous low back diagnoses and clinical findings in the physical examination. Symptoms with duration of at least 3 months overall were considered chronic. All diagnoses were categorised as 0=no, 1=probable, 2=definite. The diagnoses were classified as probable when the participant did not currently have symptoms, or when the criteria of the previous diagnoses were vague. In the current study, a clinically defined outcome was present if the participant had a probable or definite diagnosis.

Spinal problems at baseline

Low back symptoms and signs as well as spinal symptoms and signs (symptoms or signs in the thoracic or lumbar spine) were recorded at baseline by the examining physician. We used dichotomised variables (yes/no).

Weight-related factors at baseline and during follow-up

At baseline, as part of the recruit health check-up carried out during the first 2 weeks of military service, nurses or trained medics at the garrison health clinics measured the recruits’ height and weight in light clothing. For 114 men (8.2%), data on weight-related factors were not found from recruit health examination records, and we used the records of the premilitary service examination performed approximately 6 months prior to military service.

At follow-up, in addition to measured during health examination height and weight, men were asked to recall their height at the age of 20 years and weight at the age of 20, 30, 40 and 50 years.

BMI was calculated by dividing weight (kg) with the square of height (m2). At follow-up, general overweight and obesity were defined based on BMI using the WHO recommendation of BMI <25 kg/m2 (normal), 25–29.9 kg/m2 (overweight) and ≥30 kg/m2 (obese). At baseline, BMI was dichotomised into BMI <25 kg/m2 (normal) and ≥25 kg/m2 (overweight/obese).

Waist circumference was measured at follow-up. Abdominal obesity was defined based on waist circumference: <94 cm (normal), 94–101.9 cm (overweight) and ≥102 cm (obese). Waist-to-height ratio was dichotomised into ≤0.5 and >0.5.

Accuracy of self-reported height and weight

We had measured data (at baseline) and self-reported data (recalled at follow-up) for height and weight at the age of 20 years for all the men. The correlation (Pearson correlation coefficient r) was very high for height (r=0.94, p<0.0001) and moderate for weight (r=0.77, p<0.0005). We also examined the magnitude of recall bias for height at the age of 20 years by the time of recall and found that the older men recalled their height similarly to the younger men. For men aged 30 (n=124), 40 (n=194) and 50 (n=121) years at the time of Health 2000 Study data collection, we also had both self-reported as well as measured height and weight. All self-reported and measured anthropometric measures were highly correlated. For men aged 30 years, the correlation coefficients for height and weight were r=0.98 and r=0.94, respectively. For men aged 40 years, the corresponding numbers were r=0.97 and r=0.95. For men aged 50 years, the corresponding numbers were r=0.95 and r=0.98. These data suggest that recall bias is relatively minor and self-reported data could be reliably used as a proxy for participants’ height and weight. Furthermore, the correlation coefficients (Pearson r) between BMI based on measured and self-reported weight and height were 0.80, 0.85, 0.96 and 0.98, for the studied age groups, respectively.

Weight-related measures during the life course

Baseline and follow-up information of overweight or obesity based on measured BMI was used to construct a variable to describe overweight or obesity during the life course, consisting of six categories. The categories were defined as the following: 1=both baseline and follow-up BMI <25 kg/m2 (normal weight at both time points), 2=baseline BMI <25 kg/m2 and follow-up BMI ranged between 25 and 29.9 kg/m2 (became overweight during follow-up), 3=baseline BMI <25 kg/m2 and follow-up BMI ≥30 kg/m2 (became obese during follow-up), 4=baseline BMI ≥25 kg/m2 and follow-up BMI <25 kg/m2 (overweight/obese at baseline, normal weight at follow-up), 5=baseline BMI ≥25 kg/m2 and follow-up BMI ranged between 25 and 29.9 kg/m2 (overweight/obese at baseline and overweight at follow-up), 6=baseline BMI ≥25 kg/m2 and follow-up BMI ≥30 kg/m2 (overweight/obese at baseline and obese at follow-up).

A life course measure for BMI was based on repeated BMI values (measured at baseline, self-reported at the age of 30, 40 and 50 years and measured at follow-up). It was constructed by calculating age-standardised Z scores (mean=0, SD=1) for each time point measure, which were averaged across time points.

Potential confounders

Age at baseline was calculated for the day of the measurements and at follow-up for 1 June 2000. Length of education (years) was inquired at follow-up. Data on smoking and physical activity were collected at baseline and follow-up. At baseline, the conscripts were classified as smokers if they answered ‘yes’ to the question ‘Do you smoke?’. At follow-up, daily smokers were classified as smokers. At baseline, the conscripts were classified as physically active if they were participating in sports activities at least once a week. At follow-up, participants who reported that they engaged in physical exercise that causes sweating for at least 30 min at least once a week were classified as physically active.

Statistical analyses

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS V.9.4. Of 681 (28.7%) missing values on smoking at baseline, 520 values were imputed using the missing data propensity score method.21 However, 161 (6.8%) values remained missing.

Since our outcomes were based on prevalence, we used prevalence ratios (PRs) to measure the longitudinal and odds ratios (ORs) to measure the cross-sectional associations between weight-related variables and low back outcomes.

The effects of baseline and life course BMI on low back outcomes at follow-up were studied with a Cox regression model, with the total length of time of follow-up being assigned to each individual. The Cox model was used instead of logistic regression in order to avoid undue inflation of estimates of associations between weight-related measures and common low back problems.22 23 The PRs and their 95% CIs were adjusted for age and smoking status at baseline and information of education (years) obtained at follow-up.

The cross-sectional associations of weight-related measures with low back outcomes at follow-up were studied with binary logistic regression models. The participants’ age, education (years) and smoking status at follow-up were included in the multivariable models as covariates. We did not adjust for physical activity because it was not associated with low back outcomes in our study population. Furthermore, physical activity has been shown to have a U-shaped association with LBP, and was therefore considered to be an effect modifier and not a confounder.9 24

Sensitivity analyses were carried out excluding participants with spinal problems at baseline.

Results

Characteristics of the study participants and prevalence of outcomes

The characteristics of the study participants at baseline and follow-up are shown in table 1. The average follow-up time was 20.5 years (SD±6.0 years), ranging from 6 to 33 years.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population at baseline (Military Health Examination), 1967–1994 and follow-up (Health 2000 Survey), 2000–2001

| N | Mean (95% CI) | Prevalence (%, 95% CI) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | At baseline | 1385 | 19.7 (19.6 to 19.8) | |

| At follow-up | 1385 | 40.2 (39.9 to 40.5) | ||

| BMI (kg/m2) | At baseline | 1384 | 22.3 (22.1 to 22.4) | |

| At follow-up | 1385 | 26.5 (26.3 to 26.7) | ||

| Regular smokers | At baseline | 303/880 | 34.4 (31.3 to 37.7) | |

| At follow-up | 454/1380 | 32.9 (30.4 to 35.5) | ||

| Physically active at leisure time | At baseline | 447/846 | 52.8 (49.3 to 56.2) | |

| At follow-up | 1008/1370 | 73.6 (71.2 to 75.9) | ||

| Spinal symptoms and/or signs | At baseline | 208/1385 | 15.0 (13.2 to 17.0) | |

| Low back symptoms | At baseline | 113/1385 | 8.2 (6.8 to 9.7) | |

| Waist circumference | At follow-up | 1380 | 95.3 (94.8 to 95.9) | |

| Hip circumference | At follow-up | 1380 | 99.1 (98.7 to 99.5) | |

| Education (years) | At follow-up | 1366 | 12.8 (12.6 to 13.0) | |

| LBP, preceding 30 days | At follow-up | |||

| Non-specific | 393/1385 | 28.4 (26.0 to 30.8) | ||

| Radiating | 162/1385 | 11.7 (10.1 to 13.5) | ||

| Physician-diagnosed disorders* | At follow-up | |||

| Chronic low back syndrome | 100/1350 | 7.4 (6.1 to 8.9) | ||

| Sciatica | 58/1350 | 4.3 (3.3 to 5.5) |

*Information is missing for 35 men.

BMI, body mass index; LBP, low back pain.

During the follow-up, the mean BMI increased by 4.1–4.4 kg/m2 (18–20%), corresponding to 11–12 kg. The increase was linearly associated with the length of the follow-up time. Both at baseline and follow-up, about one-third of the participants were regular smokers. In general, the proportion of participants with regular physical activity was higher at follow-up than at baseline. The prevalence of spinal symptoms or signs was about 15% at baseline.

Non-specific LBP occurred commonly (table 1), whereas radiating type of LBP was less prevalent. The prevalence of radiating LBP and clinically defined outcomes increased with age (p=0.08 for radiating LBP, p=0.002 for chronic low back syndrome and p=0.01 for sciatica).

Associations of BMI with low back outcomes during the life course

BMI at baseline predicted the 1 month prevalence of radiating LBP assessed at follow-up (table 2). A one SD increase in baseline BMI, corresponding to 3 kg/m2, was associated with a 26% increase in the risk of radiating LBP. A similar trend was seen in the risk of chronic low back syndrome and sciatica assessed by a physician, although it did not reach statistical significance (table 2). Sensitivity analyses, excluding participants with baseline spinal symptoms or signs, or those with low back symptoms or signs, showed no change in the observed associations.

Table 2.

Associations of weight-related measures with LBP and physician-diagnosed low back disorders

| LBP, preceding 30 days (n=1363) |

Chronic LBP syndrome (n=1350) |

Radiating LBP, preceding 30 days (n=1363) |

Sciatica, assessed by physician (n=1350) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PR/OR | 95% CI* | PR/OR | 95% CI* | PR/OR | 95% CI* | PR/OR | 95% CI* | |

| Longitudinal associations between BMI at baseline and outcomes at follow-up | ||||||||

| BMI at baseline† | 1.07 | 0.96 to 1.19 | 1.18 | 0.96 to 1.44 | 1.26 | 1.08 to 1.46 | 1.15 | 0.89 to 1.50 |

| Life course BMI (Z score)‡ | 0.99 | 0.86 to 1.14 | 1.09 | 0.87 to 1.36 | 1.23 | 1.03 to 1.48 | 1.10 | 0.83 to 1.46 |

| Cross-sectional associations between weight-related factors, and outcomes at follow-up | ||||||||

| BMI (continuous)§ | 0.95 | 0.84 to 1.07 | 1.09 | 0.90 to 1.33 | 1.16 | 0.99 to 1.35 | 1.10 | 0.86 to 1.41 |

| BMI (categorical), kg/m2 | ||||||||

| <25 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| 25–29.9 | 1.03 | 0.80 to 1.34 | 0.95 | 0.60 to 1.51 | 1.42 | 0.97 to 2.08 | 0.84 | 0.47 to 1.51 |

| ≥30 | 0.88 | 0.61 to 1.25 | 1.13 | 0.63 to 2.00 | 1.64 | 1.02 to 2.65 | 1.04 | 0.50 to 2.15 |

| Waist circumference (continuous)¶ | 1.00 | 0.88 to 1.12 | 1.13 | 0.92 to 1.38 | 1.15 | 0.98 to 1.35 | 1.18 | 0.92 to 1.52 |

| Waist circumference (categorical), cm | ||||||||

| <94 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| 94–101.9 | 1.11 | 0.83 to 1.47 | 1.04 | 0.63 to 1.73 | 1.03 | 0.69 to 1.53 | 0.91 | 0.47 to 1.75 |

| ≥102 | 1.03 | 0.77 to 1.39 | 1.24 | 0.75 to 2.03 | 1.31 | 0.88 to 1.96 | 1.19 | 0.64 to 2.23 |

| Waist-to-height ratio | ||||||||

| Normal (≤0.5) | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | ||||

| Critical (>0.5) | 0.96 | 0.76 to 1.22 | 1.33 | 0.75 to 1.72 | 1.44 | 1.02 to 2.04 | 0.88 | 0.52 to 1.49 |

Significant associations have been marked with bold.

*PRs (for the longitudinal analyses) and ORs (for cross-sectional analyses) and their 95% CIs are adjusted for age, smoking and education.

†Continuous variable, one SD increase, corresponding to 3.0 kg/m2 for baseline BMI.

‡One unit increment in Z score, corresponding to 2.92 units of BMI during follow-up.

§Continuous variable, one SD increase, corresponding to 4.0 kg/m2 for follow-up BMI.

¶Continuous variable, one SD increase, corresponding to 11 cm for waist circumference at follow-up.

BMI, body mass index; LBP, low back pain; PR, prevalence ratio.

Life course BMI (BMI Z score) was statistically significantly associated with 1 month radiating LBP. A 1-unit increase in Z score (corresponding to 2.92 units of BMI) was associated with a 23% increase in the risk of radiating LBP (table 2). Life course BMI was not associated with the other outcomes.

Those with normal weight at baseline who substantially gained weight during the follow-up had an increased risk of 1 month radiating LBP pain assessed at follow-up (table 3). Also, those who were constantly overweight had a twofold increased risk of radiating LBP.

Table 3.

Associations of baseline and follow-up overweight and obesity with LBP

| BMI at baseline, kg/m2 | BMI at follow-up, kg/m2 | LBP, preceding 30 days (n=1363) |

Radiating LBP, preceding 30 days (n=1363) |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n* | PR† | 95% CI | n* | PR† | 95% CI | ||

| <25 | <25 | 104 (509) | 1.00 | 48 (509) | 1.00 | ||

| <25 | 25–29.9 | 161 (560) | 1.00 | 0.76 to 1.32 | 70 (560) | 1.34 | 0.89 to 2.00 |

| <25 | ≥30 | 33 (106) | 1.18 | 0.74 to 1.88 | 17 (106) | 1.91 | 1.03 to 3.53 |

| ≥25 | <25 | 2 (8) | 0.84 | 0.17 to 4.28 | 0 (8) | – | – |

| ≥25 | 25–29.9 | 21 (62) | 1.39 | 0.79 to 2.50 | 10 (62) | 2.10 | 1.00 to 4.47 |

| ≥25 | ≥30 | 26 (118) | 0.76 | 0.47 to 1.23 | 18 (118) | 1.65 | 0.89 to 3.06 |

Significant associations have been marked with bold.

*Number with outcome (number of exposed).

†PRs and their 95% CIs are adjusted for age, smoking and education.

BMI, body mass index; LBP, low back pain; PR, prevalence ratio.

Cross-sectional associations of general and abdominal obesity with low back outcomes

In cross-sectional analyses at follow-up, BMI tended to be associated with radiating LBP, but no associations were seen for the other outcomes. Waist circumference tended to be associated with radiating LBP as well as with chronic low back syndrome and sciatica (table 2).

Overweight and obesity defined by BMI showed a dose–response relationship with radiating LBP, with a 42% and 64% increase in the risk in overweight and obese men, respectively, compared to men with normal weight. Furthermore, abdominal obesity defined by waist-to-height ratio was associated with an increased risk of radiating LBP (OR=1.44, 95% CI 1.02 to 2.04). No associations were found for non-specific LBP, chronic low back syndrome or sciatica assessed by a physician (table 2). The exclusion of participants with baseline spinal symptoms or signs strengthened the observed associations between waist circumference and radiating LBP (OR=1.62, 95% CI 1.05 to 1.78 for abdominal obesity defined as waist circumference ≥102 cm).

Discussion

In our longitudinal population-based study across the life course, we found that BMI at the age of 20 years predicted radiating LBP later in life. The development of obesity during follow-up increased radiating LBP. Moreover, BMI during the life course was associated with radiating LBP later in life. General and abdominal obesity were both associated with radiating LBP with minor differences in the observed estimates. No associations were seen for non-specific LBP. Weaker and statistically non-significant associations were seen for BMI (longitudinally) and waist circumference (cross-sectionally) with the clinically defined outcomes.

The present study has several strengths. First, we used a unique study population based on the Health 2000 Study and supplemented with military service records of all men aged 30–50 years. The Health 2000 Study well represents the Finnish adult population because of the random sample and high participation rate of up to 85%. Military medical records were obtained for almost all the men in the sample. Second, general and abdominal obesity were defined based on measured weight-related indicators. In addition, we had self-reported information on weight and height for each age decennium. Third, the richness of weight-related measures allowed us to explore the associations of early indicators of obesity, change in obesity status over time, as well as life course BMI, with the outcomes. Fourth, our set of low back outcomes included symptoms as well as clinically defined disorders.

However, the findings of the current study must be interpreted taking into consideration a few limitations. Since only men were included, the population being highly representative allows generalising our findings to all men. The health examination at baseline did not provide measures of abdominal adiposity, therefore we were not able to look at the associations of abdominal obesity across the life course. Owing to the small number of overweight or obese individuals at baseline, we were not able to detect whether individuals losing weight during the follow-up are less likely to report back symptoms at the end of follow-up. Part of the weight-related measures during the life course was self-reported, and therefore recall bias may have affected the observed associations. However, our assessments confirmed the high accuracy of the self-reported values used in this study.

Our results are in agreement with a recent meta-analysis in which overweight and obesity were both consistently, though modestly, associated with the risk of lumbar radicular pain.7 Moreover, studies on associations between weight-related factors and non-specific LBP have reported inconsistent results, especially in men.6 9 25 In agreement with previous literature, we found weaker associations for the clinically defined outcomes.7 26 27

Moreover, a recent large cross-sectional study among conscripts (male and female) aged 17 years showed weaker associations of obesity with clinically defined outcomes than with symptoms among the men.28

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to report associations of low back disorders with composite life course information of BMI based on repeated measures with constant intervals. We found that BMI both at the age of 20 years and during the life course predicted radiating LBP later in life. A British birth cohort study found that high BMI at the age of 23 years predicted incidence of LBP at age 32–33 years in both genders.16 Our findings, together with those of the aforementioned study, suggest that obesity around the age of 20 years—and especially when persistent—is a causal risk factor for radiating LBP.

There are two distinct types of LBP—radiating and non-specific—that have a different course during life and may have different aetiologies.6 In line with our findings, BMI and waist circumference predicted incidence of radiating but not non-specific LBP in a population-based study among young adults.24

We measured both general obesity and abdominal adiposity. This is important, since BMI might not be an appropriate measure to capture adiposity in men.13 In agreement with our findings, a Dutch study, using a random sample from the general population, found both general and abdominal obesity to be associated with radiating but not non-specific LBP in men.14 Similarly, a recent study in a representative young adult population showed both types of adiposity being associated with the incidence of radiating LBP.24

There are several possible explanations for the association between excess weight and radiating LBP. Obesity could increase the mechanical load on the spine by causing a higher compression or tear on the lumbar spine structures. Obese people may also be more prone to injuries.29 In addition, obesity is an important risk factor for atherosclerosis, which has also been linked especially with sciatic pain.30 Since abdominal obesity showed an association with radiating LBP, systemic inflammation and patomechanical pathways involved in the metabolic syndrome may play a role, as discussed in the literature.31 A recent systematic review of twin studies concluded that individuals being overweight or obese are more likely to have LBP and lumbar disc generation, but the associations were weaker after controlling for familial factors, suggesting that obesity and LBP share common genetic risk factors.32

In conclusion, our findings indicate that being overweight or obese in young adulthood as well as during the life course increases the risk of radiating but not non-specific LBP in men. Taking into account the current global obesity epidemic, emphasis should be placed on preventive measures starting at youth and, also, preventive measures for further weight gain during the life course should be implemented. Studies on the aetiology of LBP would benefit from differentiating between radiating and non-specific types of pain. Future research should provide life course studies on the associations of weight-related factors with low back disorders among women.

Footnotes

Contributors: EV-J, SS and HF conceived and designed the study. MH and HP helped acquire the data. SS and PM analysed the data. HF wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All the authors contributed to the interpretation of the data, carefully reviewed the draft and revised it critically. All the authors gave final approval of the manuscript.

Funding: This work was supported by the Academy of Finland (129475) and the Centre for Military Medicine, Helsinki, Finland.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethics approval: The Section for Epidemiology and Public Health of the Ethics Committee of the Hospital District of Helsinki and Uusimaa approved the Health 2000 Study and The Ethics Committee of the Finnish Institute of Occupational Health further approved the MSDs@Mil study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Balague F, Mannion AF, Pellise F et al. . Non-specific low back pain. Lancet 2012;379:482–91. 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60610-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kelly T, Yang W, Chen CS et al. . Global burden of obesity in 2005 and projections to 2030. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32:1431–7. 10.1038/ijo.2008.102 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Finucane MM, Stevens GA, Cowan MJ et al. . National, regional, and global trends in body-mass index since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 960 country-years and 9.1 million participants. Lancet 2011;377:557–67. 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62037-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kautiainen S, Koivisto AM, Koivusilta L et al. . Sociodemographic factors and a secular trend of adolescent overweight in Finland. Int J Pediatr Obes 2009;4:360–70. 10.3109/17477160902811173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wang Y, Lim H. The global childhood obesity epidemic and the association between socio-economic status and childhood obesity. Int Rev Psychiatry 2012;24:176–88. 10.3109/09540261.2012.688195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shiri R, Karppinen J, Leino-Arjas P et al. . The association between obesity and low back pain: a meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol 2010;171:135–54. 10.1093/aje/kwp356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shiri R, Lallukka T, Karppinen J et al. . Obesity as a risk factor for sciatica: a meta-analysis. Am J Epidemiol 2014;179:929–37. 10.1093/aje/kwu007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shiri R, Solovieva S, Husgafvel-Pursiainen K et al. . The association between obesity and the prevalence of low back pain in young adults: the Cardiovascular Risk in Young Finns Study. Am J Epidemiol 2008;167:1110–19. 10.1093/aje/kwn007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nilsen TI, Holtermann A, Mork PJ. Physical exercise, body mass index, and risk of chronic pain in the low back and neck/shoulders: longitudinal data from the Nord-Trondelag Health Study. Am J Epidemiol 2011;174:267–73. 10.1093/aje/kwr087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heuch I, Hagen K, Zwart JA. Body mass index as a risk factor for developing chronic low back pain: a follow-up in the Nord-Trondelag Health Study. Spine 2013;38:133–9. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182647af2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mikkonen PH, Laitinen J, Remes J et al. . Association between overweight and low back pain: a population-based prospective cohort study of adolescents. Spine 2013;38:1026–33. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3182843ac8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Snijder MB, van Dam RM, Visser M et al. . What aspects of body fat are particularly hazardous and how do we measure them? Int J Epidemiol 2006;35:83–92. 10.1093/ije/dyi253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rothman KJ. BMI-related errors in the measurement of obesity. Int J Obes (Lond) 2008;32(Suppl 3):S56–9. 10.1038/ijo.2008.87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Han TS, Schouten JS, Lean ME et al. . The prevalence of low back pain and associations with body fatness, fat distribution and height. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 1997;21:600–7. 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lean ME, Han TS, Seidell JC. Impairment of health and quality of life in people with large waist circumference. Lancet 1998;351:853–6. 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)10004-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Power C, Frank J, Hertzman C et al. . Predictors of low back pain onset in a prospective British study. Am J Public Health 2001;91:1671–8. 10.2105/AJPH.91.10.1671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Heistaro S, ed. Methodology Report Health 2000 Survey. Publications of the National Public Health Institute. Helsinki: KTL-National Public Health Institute, Department of Health and Functional Capacity, 2008:1–248. http://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi-fe201204193320 (accessed 2 Jul 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aromaa A, Koskinen S, eds. Health and functional capacity in Finland—baseline results of the Health 2000 Health Examination Survey. Publications of the National Public Health Institute. Helsinki: KTL-National Public Health Institute, Finland, Department of Health and Functional Capacity, 2004:1–175. http://urn.fi/URN:NBN:fi-fe201204193452 (accessed 2 Jul 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaila-Kangas L, Leino-Arjas P, Karppinen J et al. . History of physical work exposures and clinically diagnosed sciatica among working and nonworking Finns aged 30 to 64. Spine 2009;34:964–9. 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31819b2c92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Heliovaara M, Impivaara O, Sievers K et al. . Lumbar disc syndrome in Finland. J Epidemiol Community Health 1987;41:251–8. 10.1136/jech.41.3.251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rosenbaum PR, Rubin DB. The central role of the propensity score in observational studies for causal effects. Biometrika 1983;70:41–55. 10.1093/biomet/70.1.41 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barros AJ, Hirakata VN. Alternatives for logistic regression in cross-sectional studies: an empirical comparison of models that directly estimate the prevalence ratio. BMC Med Res Methodol 2003;3:21 10.1186/1471-2288-3-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thompson ML, Myers JE, Kriebel D. Prevalence odds ratio or prevalence ratio in the analysis of cross sectional data: what is to be done? Occup Environ Med 1998;55:272–7. 10.1136/oem.55.4.272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shiri R, Solovieva S, Husgafvel-Pursiainen K et al. . The role of obesity and physical activity in non-specific and radiating low back pain: the Young Finns study. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2013;42:640–50. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2012.09.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kääria S, Leino-Arjas P, Rahkonen O et al. . Risk factors of sciatic pain: a prospective study among middle-aged employees. Eur J Pain 2011;15:584–90. 10.1016/j.ejpain.2010.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heliövaara M, Mäkela M, Knekt P et al. . Determinants of sciatica and low-back pain. Spine 1991;16:608–14. 10.1097/00007632-199106000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jhawar BS, Fuchs CS, Colditz GA et al. . Cardiovascular risk factors for physician-diagnosed lumbar disc herniation. Spine J 2006;6:684–91. 10.1016/j.spinee.2006.04.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hershkovich O, Friedlander A, Gordon B et al. . Associations of body mass index and body height with low back pain in 829,791 adolescents. Am J Epidemiol 2013;178:603–9. 10.1093/aje/kwt019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hu HY, Chou YJ, Chou P et al. . Association between obesity and injury among Taiwanese adults. Int J Obes 2009;33:878–84. 10.1038/ijo.2009.122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shiri R, Viikari-Juntura E, Leino-Arjas P et al. . The association between carotid intima-media thickness and sciatica. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2007;37:174–81. 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2007.03.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Samartzis D, Karppinen J, Cheung JP et al. . Disk degeneration and low back pain: are they fat-related conditions? Global Spine J 2013;3:133–44. 10.1055/s-0033-1350054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dario AB, Ferreira ML, Refshauge KM et al. . The relationship between obesity, low back pain, and lumbar disc degeneration when genetics and the environment are considered: a systematic review of twin studies. Spine J 2015;15:1106–17. 10.1016/j.spinee.2015.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]