Abstract

Numerous genetic factors that influence breast cancer risk are known. However, approximately two-thirds of the overall familial risk remain unexplained. To determine whether some of the missing heritability is due to rare variants conferring high to moderate risk, we tested for an association between the c.5791C>T nonsense mutation (p.Arg1931*; rs144567652) in exon 22 of FANCM gene and breast cancer. An analysis of genotyping data from 8635 familial breast cancer cases and 6625 controls from different countries yielded an association between the c.5791C>T mutation and breast cancer risk [odds ratio (OR) = 3.93 (95% confidence interval (CI) = 1.28–12.11; P = 0.017)]. Moreover, we performed two meta-analyses of studies from countries with carriers in both cases and controls and of all available data. These analyses showed breast cancer associations with OR = 3.67 (95% CI = 1.04–12.87; P = 0.043) and OR = 3.33 (95% CI = 1.09–13.62; P = 0.032), respectively. Based on information theory-based prediction, we established that the mutation caused an out-of-frame deletion of exon 22, due to the creation of a binding site for the pre-mRNA processing protein hnRNP A1. Furthermore, genetic complementation analyses showed that the mutation influenced the DNA repair activity of the FANCM protein. In summary, we provide evidence for the first time showing that the common p.Arg1931* loss-of-function variant in FANCM is a risk factor for familial breast cancer.

Introduction

Breast cancer (OMIM #114480) is a common oncological disease that accounts for 23% of all malignancies in women and is estimated to cause 1 400 000 new cases and more than 450 000 deaths worldwide every year (1). It has been estimated that ∼13% of all breast cancer cases have one or more affected relatives and that risks of breast cancer increase with greater numbers of affected relatives (2). This increased risk is also due to known germ-line susceptibility alleles including rare, high-risk loss-of-function variants predominantly found in BRCA1 and BRCA2 (3). In addition, 94 common single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) have been identified that individually confer only a slightly increased risk of breast cancer, but combined in a multiplicative model account for ∼16% of familial breast cancer risk (4).

BRCA1 and BRCA2 gene products contribute to cell homeostasis through the DNA damage response mediated by homologous recombination. Moreover, mutations in BRCA2 (also known as FANCD1) have been shown to cause Fanconi Anaemia (FA), a rare recessive disorder characterized by genomic instability, progressive bone marrow failure and predisposition to cancer. These genes encode proteins belonging to the FA pathway, which becomes activated in response to breaks in single- and double-stranded DNA. Monoallelic variants in several of these genes, including ATM, PALB2/FANCN and RAD51C/FANCO, have been detected in non-BRCA1 and BRCA2 familial breast cancer cases, but at a lower frequency in controls, consistent with moderate to high risks of breast cancer (5–7). The rare variants identified in these genes have a cumulative frequency in familial cases of 0.5–2%. However, with the exception of a few recurrent or founder mutations in specific populations, each of these mutations is generally very rare with many reported in single families. In contrast, few rare truncating and pathogenic missense variants have been found in CHEK2 (8), with much of the risk attributed to this gene explained by the single moderate-penetrance founder allele, c.1100delC (9).

Recent studies have underlined the challenges in identifying new breast cancer predisposition genes. Exome sequencing in families followed by gene re-sequencing in additional cases and controls have provided conflicting results for XRCC2 (10,11), and inconclusive results for FANCC and BLM (12), raising questions about the statistical power of these studies (13). Similarly, the evidence that SLX4, an FA gene, is associated with breast cancer risk is limited, given that the analysis of large numbers of familial cases identified only three inactivating variants (14–16).

Screening for risk-associated mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 is commonly used in clinical practice to identify at-risk individuals and to direct them towards specific surveillance programmes or risk reduction options. By including additional breast cancer predisposition genes in gene panels analysed by next-generation sequencing, risk prediction can be performed in a larger fraction of individuals at a reduced cost with rapid turnaround time. With the goal of identifying new risk-associated genes, we and others previously performed exome sequencing in multiple-case breast cancer families (17). One of the findings of that study was a single proband heterozygous for the c.5791C>T variant (rs144567652) in FANCM, another gene involved in the FA pathway. The variant was predicted to introduce a stop codon (TGA) in exon 22, causing the loss of 118 amino acids from the C-terminus (p.Arg1931*). A subsequent case–control study detected the mutation in 10 of 3409 (0.29%) familial cases without known mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 and in 5 of 3896 (0.13%) controls from different national studies. The estimated odds ratio (OR) was 2.29 [95% confidence interval (CI) = 0.71–8.54; P = 0.13]. In an effort to establish the significance of this estimate (17), a further analysis in a larger cohort was performed.

Results

Association with breast cancer risk

We investigated the c.5791C>T mutation in a large series of familial cases without known mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 and in a comparable set of control individuals from Italy, France, Spain, Germany, Australia, USA, Sweden and The Netherlands. The mutation was found in 18 of 8635 (0.21%) cases (pedigrees are shown in Supplementary Material, Fig. S1) and in 4 of 6625 (0.06%) controls (Table 1) giving a statistically significant association with breast cancer risk with an age-adjusted OR of 3.93 (95% CI = 1.28–12.11; P = 0.017). The c.5791C>T mutation is rare and we observed a large variation in allele frequency in cases and controls across studies. To control for population stratification, we performed a meta-analysis, including only studies in which mutation carriers were detected in both cases and controls (Italy, France and Australia). Starting from the ORs and their 95% CIs obtained from a univariate logistic model within each country, we obtained a pooled OR = 3.67 (95% CI = 1.04–12.87; P = 0.043) (Table 2). A second meta-analysis was performed by exploiting all the available data. We implemented an exact conditional logistic regression model including ‘country’ as a random covariate in order to control for population stratification and for the absence of variant carriers in some countries (Sweden and USA) [OR = 3.330 (95% CI = 1.087–13.615; P = 0.0320)].

Table 1.

Number and frequency of mutation carriers and non-carriers in cases and controls

| Geographical group | Country | Cases |

Controls |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carriers | Non-carriers | Freq% | Carriers | Non-carriers | Freq% | ||

| South/Western Europe | Italy | 6 | 2209 | 0.27 | 1 | 1483 | 0.07 |

| France | 5 | 1570 | 0.32 | 1 | 1323 | 0.08 | |

| Spain | 3 | 751 | 0.40 | 0 | 286 | NA | |

| All | 14 | 4530 | 0.31 | 2 | 3092 | 0.06 | |

| Non-South/Western Europe | Germany | 0 | 1636 | NA | 1 | 1899 | 0.05 |

| Australia | 3 | 1235 | 0.24 | 1 | 1164 | 0.09 | |

| USA | 0 | 517 | NA | 0 | 322 | NA | |

| Sweden | 0 | 484 | NA | 0 | 0 | NA | |

| The Netherlands | 1 | 215 | 0.46 | 0 | 144 | NA | |

| All | 4 | 4087 | 0.10 | 2 | 3529 | 0.06 | |

| All populations | Total | 18 | 8617 | 0.21 | 4 | 6621 | 0.06 |

NA, not applicable.

Table 2.

Meta-analysis of the study results from countries with mutation carriers in both cases and controls

| Country | Cases |

Controls |

OR | 95% CI | P-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carriers | Non-carriers | Freq% | Carriers | Non-carriers | Freq% | ||||

| Italy | 6 | 2209 | 0.27 | 1 | 1483 | 0.07 | 4.03 | 0.48−33.47 | 0.197 |

| France | 5 | 1570 | 0.32 | 1 | 1323 | 0.08 | 4.21 | 0.49−36.10 | 0.189 |

| Australia | 3 | 1235 | 0.24 | 1 | 1164 | 0.09 | 2.82 | 0.24−27.13 | 0.369 |

| Pooled | 14 | 5014 | 0.28 | 3 | 3970 | 0.08 | 3.67 | 1.04−12.87 | 0.043 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Expression of the mutant allele

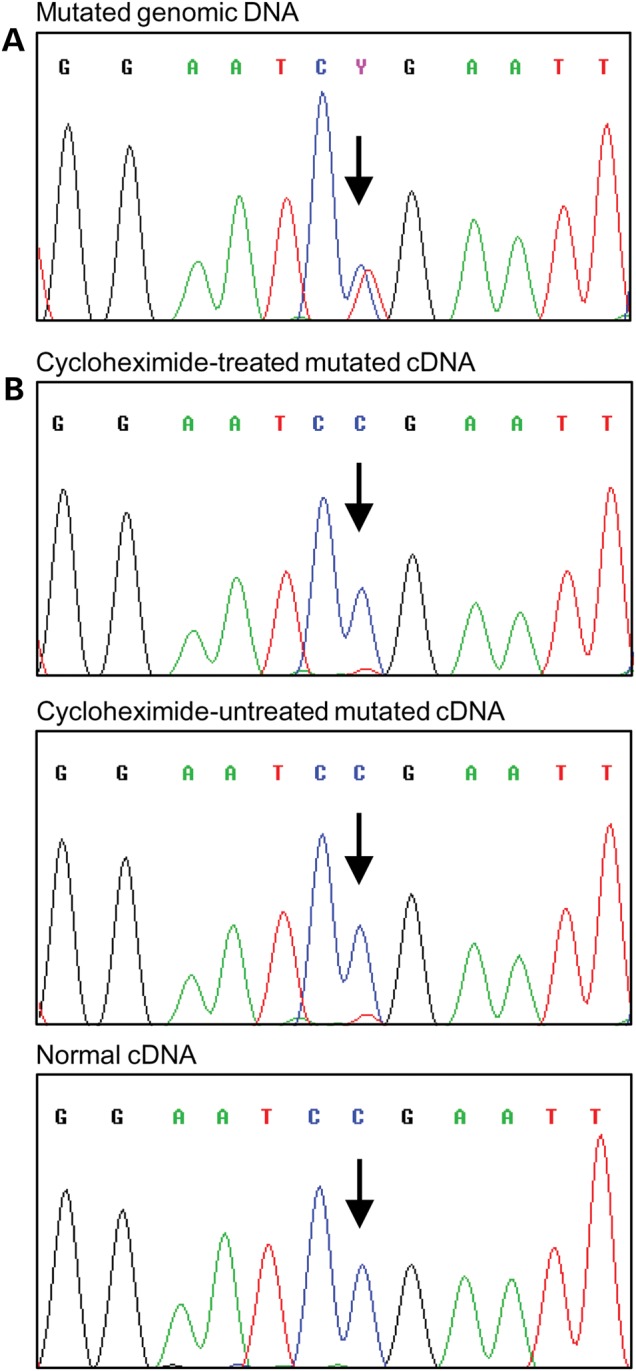

To verify the functional consequences of the c.5791C>T mutation, we first performed reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) in lymphoblastoid cell lines (LCLs) derived from two mutation carriers. Amplifying a product spanning exons 22 and 23, sequence analyses revealed very low levels of the mutated transcript compared with corresponding normal mRNA. Treatment with a protein synthesis inhibitor, cycloheximide, did not alter mutant transcript levels (Fig. 1), suggesting that the effect was probably not related to nonsense-mediated decay (NMD), but rather to a defect in mRNA splicing itself.

Figure 1.

Sequencing analysis of the FANCM gene and transcript. (A) Genomic DNA fragment PCR amplified using both primers in exon 22 from an LCL carrying the c.5791C>T mutation. (B) cDNA fragment amplified by PCR using a forward primer in exon 22 and a reverse primer in exon 23. A strong reduction in the expression of the mutant allele was observed in both cycloheximide treated and untreated cells. cDNA from a non-carrier individual was used as a control. The position of the mutation is indicated by the arrows. Identical results were observed in an additional mutated LCL.

Effect on the mRNA splicing

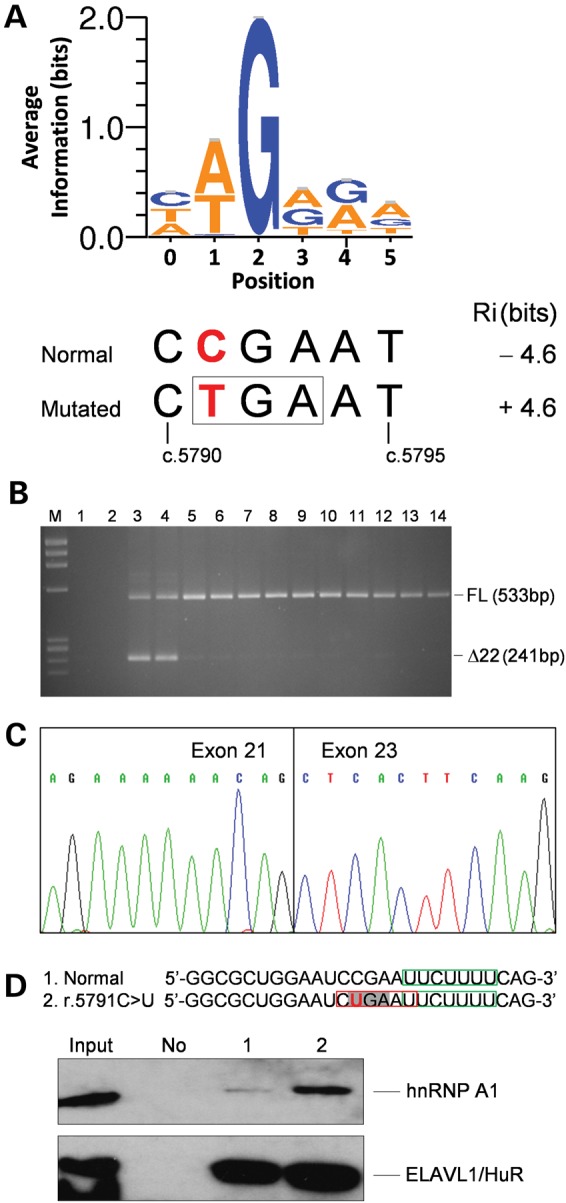

The occurrence of exonic mutations affecting pre-mRNA splicing is well documented in many human disease genes (18). These include nonsense mutations, a phenomenon referred to by some authors as ‘nonsense-associated altered splicing’ (19). Therefore, to assess the impact of c.5791C>T on splicing regulatory binding sites controlling exon definition, we performed information theory-based mutation analysis, using the Automated Splice Site and Exon Definition Analysis (ASSEDA) server (20). The variant was predicted to create a strong binding site [information content (Ri) = 4.6 bits] for the splicing factor hnRNP A1 at position c.5790_5795 (Fig. 2A) (21). Exon definition analysis suggested that the creation of this site would completely suppress exon recognition (Ri,total from 3.5 to −2.5 bits), predicted to result in exon skipping. This was confirmed by RT-PCR, using forward and reverse primers in exons 21 and 23 which detected two amplification products (Fig. 2B). The upper band derived from the full-length transcript (Supplementary Material, Fig. S2), whereas the lower band derived from an aberrant transcript lacking the entire exon 22 (c.5717_6008del292) (Fig. 2C). This exon skipping is predicted to encode a protein that incorporates 11 additional residues and to lead to a premature termination of translation that results in the loss of 132 amino acids from the FANCM C-terminus (p.Gly1906Alafs12*).

Figure 2.

Analysis of the effect of the FANCM c.5791C>T mutation on RNA. (A) Sequence logo of hnRNP A1 binding sites generated as described in Materials and Methods. The opal codon (TGA, boxed) introduced by the FANCM c.5791C>T mutation (in bold red) is contained at positions 1–3 of the hnRNP A1 binding-site encompassing nucleotides c.5790_5795. The hnRNP A1 binding-site strength computed by the ASSEDA software for the normal and mutated sequences is reported. (B) Agarose gel electrophoresis of the RT-PCR products using a forward primer in exon 21 and a reverse primer in exon 23. M, molecular marker (ΦX-174 HaeIII digested); 1, no template as a negative control for PCR; 2, genomic DNA as a negative control for the specificity of cDNA amplification; 3 and 4, cDNAs from LCLs carrying the c.5791C>T mutation; 5–14, cDNAs from LCLs derived from 10 mutation negative individuals, used as reference controls. The sizes of the full-length (FL) and Δexon22 (Δ22) transcripts are indicated. (C) Sequence of the aberrant band excised from the gel showing the skipping of the entire exon 22. (D) Western blot analysis of biotin RNA–hnRNP A1 protein pull down using a goat polyclonal antibody. The sequence of the used RNA oligonucleotides encompassing FANCM positions r.5779_5804 is reported, with the r.5791C>U mutation in bold red, the opal codon enlightened in light grey and the predicted hnRNP A1 binding site created by the mutation boxed in red. As a control for the pull-down efficiency and specificity, we used an antibody against the ELAVL1/HuR protein for which a binding site, boxed in green, is predicted in both RNA oligonucleotides. Input, 10% of total HeLa cell line extract used in the pull-down assay. No, no RNA used as a negative control; 1, normal RNA; 2, RNA carrying the r.5791C>U mutation. The results shown here are representative of two independent experiments.

Skipping of exon 22 is mediated by hnRNP A1

A pull-down experiment with HeLa cell extracts followed by western blot analysis showed that the hnRNP A1 protein specifically bound to RNA oligonucleotides spanning FANCM position r.5779_5804 and carrying the r.5791C>U mutation, whereas a very weak interaction was observed with the corresponding normal oligonucleotide (Fig. 2D). These results are in agreement with the outcomes of the in silico analyses and provide evidence that the mechanism through which the c.5791C>T mutation causes exon 22 skipping is mediated by the binding of hnRNP A1 protein.

DNA repair activity-based functional studies

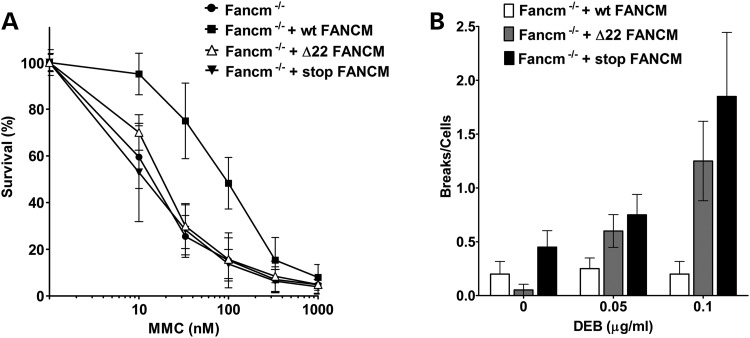

We then checked whether the c.5791C>T mutation (Δ22) affects FANCM activity in DNA repair, by genetic complementation of the following FA-associated cell phenotypes: hypersensitivity to mitomycin C (MMC)- and diepoxybutane (DEB)-induced chromosome fragility. As an internal control, we used a previously described nonsense mutation (p.S724X; rs137852864) (22) that leads to a premature stop codon (stop). Mutant cDNAs were generated by site-directed mutagenesis and cloned into lentiviral vectors to stably transduce Fancm−/− immortalized mouse embryonic fibroblast (MEFs). Wild-type, Δ22 and stop alleles were expressed at similar levels in infected cells (Supplementary Material, Fig. S3). As expected, wt FANCM but not the prematurely truncated forms rescued MMC hypersensitivity of Fancm−/− MEFs (Fig. 3A). Similar results were observed in a chromosome fragility assay (Fig. 3B). These observations lead to the conclusion that the Δ22 form of FANCM is deficient in DNA repair of MMC- and DEB-induced stalled replication forks.

Figure 3.

Functional studies of the FANCM mutation. (A) Analysis of cellular MMC sensitivity. MEFs expressing Δ22-FANCM allele (Fancm−/− + Δ22 FANCM) are more sensitive to MMC than the cell expressing the wt FANCM allele (Fancm−/− + wt FANCM). Not transduced MEFs (MEF Fancm−/−) and MEF Fancm−/− expressing a FANCM with loss-of-function mutation p.S724X (Fancm −/− + stop FANCM) are used as controls (N = 3; error = standard deviation). (B) Chromosome fragility induced by DEB treatment. Fancm−/− + Δ22 FANCM and Fancm−/− + stop FANCM cells show higher chromosome fragility than Fancm−/− + wt FANCM. Twenty metaphases were analysed for chromosome breaks. Results are represented as mean number of breaks per cells and the error bars are SEM.

Discussion

Genotyping of the c.5791C>T variant from FANCM in 8635 familial cases with no mutations in BRCA1 and BRCA2 and in 6625 control individuals from Italy, France, Spain, Germany, Australia, USA, Sweden and The Netherlands indicate that the variant is associated with risk of breast cancer with OR of 3.93. The association between the variant and breast cancer risk is reinforced if the data from the present case–control analysis are combined with those of Gracia-Aznarez et al. (17). Overall, the variant was detected in 28 of 12 044 (0.23%) familial cases and 9 of 10 521 (0.09%) controls, corresponding to a naive OR, adjusted for the ‘study’ covariate, of 2.83 (95% CI = 1.33–6.01; P = 0.007). It has to be noted that these studies were based on cases with positive family history for breast cancer and/or disease early onset. These selected cases are likely to be enriched in predisposing genetic factors. Consequently, the ORs observed here could be higher than those expected in unselected cases and population controls.

Population stratification may occur when a rare mutation is tested in individuals from different countries. We took into consideration this critical issue by performing two meta-analyses. The first was based only on studies with carriers in both cases and controls, whereas the second exploited all the individual data. Both analyses supported the c.5791C>T mutation as a breast cancer risk factor (OR = 3.67 and 3.33, respectively), although with borderline statistical significance. However, these analyses do not completely guard against stratification effect. Hence, these results need to be taken with caution. In this light, genotyping of additional variants in much larger series of unselected breast cancer cases and matched controls will be needed to confirm FANCM as a breast cancer susceptibility gene.

The functional characterization of the mRNA transcript derived from the c.5791C>T allele shows that the variant causes the skipping of exon 22 introducing a premature stop codon. In addition, genetic complementation assays revealed the mutated protein lacks DNA repair activity. These results support that the FANCM c.5791C>T mutation is pathogenic. Of note, our observations at the mRNA level emphasize the notion that, although nonsense mutations are usually considered as inherently deleterious, transcript analyses are required for a precise assessment of actual functional consequences.

Interestingly, while this article was in preparation, another FANCM C-terminus truncating mutation, the c.5101C>T (p.Q1701*), was detected by the exome sequencing of 11 Finnish breast cancer families (23). The c.5101C>T mutation was shown to be significantly more frequent in Finnish breast cancer cases compared with controls (OR = 1.86; 95% CI = 1.26–2.75; P = 0.0018), to have higher effect in cases with family history (OR = 2.11; 95% CI = 1.34–3.32; P = 0.0012)—although incomplete co-segregation with the disease was observed among most of the families—and with the stronger effect (OR = 3.56; 95% CI = 1.81–6.98; P = 0.0002) in mutation carriers affected with triple-negative (oestrogen receptor-, progesterone receptor- and HER2-negative) breast cancer (TNBC). In addition, the age at breast cancer diagnosis was not different between variant carriers and non-carriers and the variant allele was not subjected to mRNA NMD (23). Among the cases we studied, there were no significant differences in age at breast cancer diagnosis in the 18 variant carriers versus the non-carriers (data not shown). Moreover, because variant carriers with TNBC were not found, it was not possible to associate the c.5791C>T mutation with this specific tumour subtype (see Supplementary Material, Table S1). Our data, together with the observations by Kiiski et al., support the notion that loss-of-function mutations of FANCM are moderate breast cancer risk factors. Additional studies, such as modified segregation-analysis in families, are warranted to provide age-specific risk estimates for FANCM mutation carriers.

The 1100delC allele of CHEK2 has a number of properties similar to c.5791C>T in FANCM. This allele has been shown to be associated with moderate risk and has been found in many countries with a frequency that is higher in North-Eastern Europe and decreases in Southern Europe (9). Taking into consideration the geographic origin of the individuals included in our study, we observed that the frequency of the mutation carriers in South-Western European countries (16/7638 = 0.21%) was higher, although with borderline statistical significance (Fisher's exact test, P = 0.052), than that observed in all other countries evaluated (6/7622 = 0.08%) (Table 1). This suggests that this FANCM mutation has a frequency gradient that is opposite of that reported for the CHEK2 1100delC. Nevertheless, the relatively small numbers of carriers observed suggest that further analyses in specific populations would be worthwhile. For example, data from the Exome Aggregation Consortium (ExAC), Cambridge, MA (http://exac.broadinstitute.org) (March 2015, accessed), that is collecting exome sequencing data from individuals included in various disease-specific and population genetic studies, indicate that c.5791C>T occurs in the Finnish population with a carrier frequency of nearly 1%.

The FA pathway is generally subdivided into upstream proteins, assembling into the ‘core complex’ and ‘downstream effectors’. The ‘core complex’ ubiquitinates the FANCI–FANCD2 complex and this activates the pathway coordinating the action of the downstream effectors. The latter include FANCD1/BRCA2, FANCN/PALB2, FANCJ/BRIP1 and FANCO/RAD51C that are required for DNA repair by homologous recombination and are all breast cancer genes (24). This has suggested that the involvement of FA genes in breast cancer susceptibility could be limited to the FA downstream effectors (24,25). The FANCM protein has different functional domains, including a DEAH translocase domain at the N-terminus, and domains for interaction with proteins mediating DNA binding between amino acids 675 and 790 for interaction with MHF1 and MHF2, and at the C-terminus beyond amino acid 1799, for interaction with FAAP24 (26). Moreover, FANCM–FAAP24–MHF1–MHF2 acts as an independent ‘anchor complex’ that recognizes the damage caused by interstrand cross-linking agents and recruits the FA core complex (26). Furthermore, FANCM is not essential for complete ubiquitination of the FANCI–FANCD2 complex (24,26). Finally, the FANCM/MHF complex has a translocase activity that is independent of the core complex proteins (27). Hence, FANCM has a direct activity in maintaining the DNA integrity that can be independent of the FA pathway. In this light, it is possible that the increased risk for breast cancer conferred by the c.5791C>T variant is due to a direct impairment of the DNA damage response as for the FA downstream effectors.

BRCA1 and BRCA2 are established breast cancer risk factors with high penetrance and PALB2 was also recently shown to confer a high breast cancer risk (28). Although these three genes encode for downstream effectors of the FA pathway, their proteins are also involved in other DNA damage responses, including double-strand break repair. Thus, BRCA1, BRCA2 and PALB2 exert DNA damage response functions that one can speculate to be of greater magnitude than FANCM. Consequently, susceptibility to breast cancer is expected to be higher in BRCA1, BRCA2 or PALB2 mutation carriers and lower in carriers of FANCM mutations, which is in agreement with our data on the c.5791C>T mutation and similar data on the c.5101C>T mutation (23). By analogy, the abrogation of BRCA1, BRCA2 and PALB2 functions on the one hand, and the abrogation of FANCM function on the other, seem to impact FA differentially. It is known that biallelic BRCA2 and PALB2 mutations cause FA, and recently, initial evidence of the involvement of BRCA1 mutations in the disease have been documented. BRCA1 biallelic mutations were found in a woman showing anomalies consistent with a FA-like disorder, which supports BRCA1/FANCS as a novel FA gene (29). In contrast, the role of FANCM in FA is questionable. The only FA patient reported so far with truncating FANCM mutations also carried deleterious mutations in FANCA (22,30). Moreover, individuals homozygous for the truncating FANCM mutations c.5101C>T and c.5791C>T did not present with FA (31) indicating that, at present, FANCM cannot be considered to cause FA.

In conclusion, based on the analysis of large sets of cases and controls and functional observations, our study provides evidence that the FANCM c.5791C>T is a novel risk factor for familial breast cancer.

Materials and Methods

Study populations

Twenty-five case–control cohorts were included in the study through a collaboration call circulated among the COMPLEXO participants (32). Centre or study details, number and description of cases and controls are reported in Supplementary Material, Table S2. The cases included in this study were (i) affected with breast cancer at age ≥18, (ii) eligible to BRCA1- and BRCA2-mutation testing based on breast and/or ovarian cancer family history (at least one first- or second-degree female relatives with either tumours), or because affected with early onset (≤40 years) or bilateral (≤50 years) breast cancer and (iii) negative to BRCA1- and BRCA2-mutation test. A few of the centres or studies contributing to this article used slightly different inclusion criteria, and these are described in Supplementary Material, Table S2. In all cohorts, cases and controls were female Caucasians recruited in the same area. All individuals included in the study signed an informed consent to the use of their biological samples for research purposes. The participation to this study was approved by ethical committees or review boards of the participant centres or studies.

Mutation genotyping

Details of genotype analyses for FANCM (NG_007417.1, NM_020937.2) c.5791C>T mutations are reported in Supplementary Material, Table S2. For most studies, cases and controls were genotyped at coordinating centre (IFOM, Milano) by custom TaqMan SNP genotyping assay (Life Technologies) using the following primers and probes. Forward primer: 5′-AGCCTGCTGACTACCTTAATTGG-3′; reverse primer: 5′-CTTTAGCAAATCTGCGGTTTCTTCT-3′; probe 1: 5′-TGAAAAGAATTCGGATTCC-3′; probe 2: 5′-TGAAAAGAATTCAGATTCC-3′. In every 96-well plate, at least one positive control and two blank controls were included. The remaining samples were genotyped at local centres using TaqMan assay or high-resolution melting. All positive samples were confirmed by double-strand Sanger sequencing. Two studies (SWE-BRCA and MAYO) provided genotyping data from previous next-generation sequencing studies.

Statistical analyses

Logistic regression analysis was used to test the association between mutation frequencies and risk of breast cancer (33). Age was included in the model as adjustment covariate and the adjusted ORs and its 95% CIs were estimated. A meta-analysis considering only countries in which mutation carriers were observed in both cases and controls was performed based on mixed models (34) starting from single-study estimates. A meta-analyses exploiting all individual data was performed using an exact conditional logistic regression model (35). The statistical analyses were performed with the SAS software (Version 9.2; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

Information theory-based mutation analyses

The ASSEDA server (http://mutationforecaster.com) has been developed to predict the molecular phenotype of putative splicing mutations (20) and implemented to take into account their effect on splicing factor binding sites. In particular, CLIP-seq libraries for hnRNP A1 (36) were used to derive information theory-based position weight matrix (PWM), depicted in Figure 2A. PoWeMaGen software, which uses Bipad (37) to generate minimum entropy alignments, generates a series of potential binding-site models over a range of input parameters. To mitigate against phasing the alignment on natural splice sites instead of adjacent hnRNP A1 binding sites, models were built from shorter sequences, ranging in lengths between 18 and 25 nucleotides (nt). The optimal model was determined by maximizing incremental information by varying binding-site length (6–10 nt), number of Monte Carlo cycles (250–5000) and allowing either zero or only one site per sequence (OOPS). The model with the highest average information used a maximum fragment length of 18 nt, 1000 Monte Carlo cycles, OOPS and a single-block binding-site length of 6 nt. This sequence is frequently present in sites cross-linked to hnRNP A1 protein (34). Of the 140 431 hnRNP A1 binding sites used to create the information theory-based model, the wild-type sequence, CCGAAT, is not represented, and the mutant site, CTGAAT, occurred 716 times. The model was validated with known hnRNP A1 binding sites and splicing affecting mutations (38–41). The effects of mutations at hnRNP A1 sites on exon definition were determined from the total information content (Ri,total), by incorporating changes in the strengths of these sites, corrected for the gap surprisal, which represents the distance between the hnRNP A1 site and the natural splice site. Gap surprisal values were determined by scanning the genome for hnRNP A1 sites with the PWM, and then determining the frequency of each interval length between known natural sites and the nearest hnRNP A1 site, separately for exons and introns. Differences between the natural and mutated exon Ri,total values correspond to changes in the abundance of the respective isoforms and can predict exon skipping. The calculation is carried out by the ASSEDA server (20). Exon definition analysis was validated for a set of mutations that affect hnRNP A1 binding-site strength (39,40).

Cell lines

Epstein–Barr virus-immortalized human LCLs were established from peripheral blood derived from 2 carriers of the c.5791C>T mutation and 10 normal controls (42). LCLs were maintained in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with 15% foetal bovine serum plus 1% penicillin–streptomycin. The HeLa cell line was cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% foetal calf serum plus 1% penicillin–streptomycin at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 atmosphere. The HeLa cell line was authenticated by short tandem repeat analysis using the kit GenePrint10 kit (Promega). Fancm−/− immortalized MEFs (43) were a kind gift of Dr H. Te Riele from The Netherlands Cancer Institute, Amsterdam. MEFs were cultured in DMEM 10% fetal calf serum supplemented with antibiotics. All the cell lines used in this study were routinely checked for mycoplasma contamination using the PCR Mycoplasma Detection Set (Takara) or the MycoAlert™ Mycoplasma Detection Kit (Lonza).

Transcript analyses

Potential degradation of unstable transcripts containing premature termination codons via nonsense-mediated mRNA decay (NMD) was prevented by growing LCLs in the presence of cycloheximide (100 µg/ml) for 4 h. Total RNA was purified from LCLs using the Nucleospin RNA II (Macherey-Nagel) and the cDNA was synthesized using random primer and Maxima H Minus Enzyme (Thermo Scientific), according to the manufacturers’ protocols. cDNAs were PCR amplified using the following primers. Exon 21, forward: 5′-CAAGTTCATTGAGCAGATCCAG-3′; exon 22, forward: 5′-ACATCAAGGATGTTTAGGA-3′; exon 22, reverse: 5′-GTGCCTCACTTTTATTACTA-3′; exon 23, reverse: 5′-CCCATCTTGAGCAGCTTGA-3′. Amplification products were visualized on agarose gel stained with ethidium bromide and directly characterized by Sanger sequencing. Alternatively, single PCR fragments were excised from the gel, purified using the Wizard® SW Gel and PCR Clean-Up System (Promega) and sequenced.

Biotin RNA–protein pull-down assay

Protein extraction was performed starting from ∼5 × 106 HeLa cells. These cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4°C for 5 min, washed twice with 1× phosphate buffered saline (PBS) and lysed in lysis buffer [25 mm Tris (pH 7.4), 150 mm NaCl, 1 mm ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid, 1% Nonidet P-40, 5% glycerol] containing protease inhibitor (Sigma–Aldrich), on ice for 30 min. Following centrifugation, the protein concentration was determined by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad). Mutated and normal RNA oligonucleotides were biotinylated at the 3′ end using the RNA 3′ End Desthiobiotinylation Kit (Thermo Scientific Pierce), according to the manufacturer's instructions. For each binding reaction, 50 pmol of biotinylated RNA oligonucleotides were coupled to 50 μl of Streptavidin Magnetic Beads (Thermo Scientific Pierce) and incubated with an equal amount of HeLa cell lysates in 1× protein–RNA binding buffer [0.2 M Tris (pH 7.5), 0.5 M NaCl, 20 mm MgCl2, 1% Tween-20 detergent], for 2 h at 4°C with agitation. The bound proteins were eluted from the magnetic beads by incubating with 50 μl of biotin elution buffer (Thermo Scientific Pierce) for 30 min at 37°C with agitation. The eluted proteins were subjected to 4–15% sodium dodecyl sulphate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis gradient gel and visualized by western blotting using a goat polyclonal antibody against hnRNP-A1 (#sc-10029, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) or a mouse monoclonal antibody against ELAVL1/HuR (#1862775, Thermo Scientific Pierce). The binding site for the ELAVL1/HuR protein was identified with ASSEDA (http://splice.uwo.ca/logos.html).

Plasmids used for functional studies

The doxycycline-inducible lentiviral vector pLVX-TRE3G-FANCM was kindly provided by Dr N. Ameziane (Vrije Universiteit Medical Center, Amsterdam, The Netherlands) and mutated by site-directed mutagenesis with the QuickChange II XL Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (Agilent Technologies), as previously described (42) and using the following PAGE purified mutagenic primers. Δ22 primer 1: 5′-GAAAAGGACAGAGAAAAAACAGCTCACTTCAAGAAATCTCCATG-3′, Δ22 primer 2: 5′-CATGGAGATTTCTTGAAGTGAGCTGTTTTTTCTCTGTCCTTTTC-3′, c.2171C>A primer 1: 5′-TGAGGAAAACAAACCAGCTCAAGAATAAACCACTGGAATTC-3′ and c.2171C>A primer 2: 5′-GAATTCCAGTGGTTTATTCTTGAGCTGGTTTGTTTTCCTCA-3′. The sequences of all FANCM constructs were verified by Sanger sequencing to confirm that they only bore the intended mutations.

Lentiviral particles production and cell transduction

To prepare lentiviral particles, 5 × 106 HEK-293 T cells were plated into 10 cm dishes. The next day, medium was changed with a fresh one containing 30 µm Chloroquine (Sigma) and cells were transfected with the lentiviral expression vectors and the helper plasmids (PAX and ENV) using the CalPhos Mammalian Transfection Kit (Clontech). The medium was changed 24 h after transfection, and 24 h later, the lentivirus-containing supernatant was collected and filtered through a 0.45 µm filter (Millipore). Additional supernatant was collected after additional 24 h, filtered and pooled with the initial one. Pooled supernatants were centrifuged in a Beckman JS-24.38 rotor at 19 500 rpm for 1.5 h at 4°C. Pellets were resuspended in PBS (50 µl of PBS/10 ml of supernatant) and stored at −80°C. Sixty thousands of Fancm−/− MEFs per well were seeded in a 12-well plate. After 24 h, cells were infected with 20 µl of concentrated viral supernatant in the presence of 1 µg/ml polybrene (Millipore). Twenty-four hours later, infected cells were selected with puromycin (2.5 µg/ml). Transgene expressions were checked by real-time PCR.

MMC sensitivity test

Twenty-five thousand cells of each cell line were seeded in 2 ml of complete medium supplemented with 2 µg/ml doxycycline in 12 wells of 6-well plates. The next day, MMC was added at the indicated doses and the cell sensitivity was evaluated 72 h after cell cultures were washed with PBS. Cells were collected in a volume of 300 µl of trypsin and 700 µl of complete medium and counted with a Z2™ coulter counter (Beckman Coulter) (44).

Chromosome fragility test

Two hundred thousand cells were seeded in complete medium supplemented with 2 µg/ml doxycycline. Twenty-four hours later, DEB was added at the indicated concentrations, and metaphase spreads were then harvested 3 days later as it follows. Colcemid™ (Sigma) was added at 0.1 µg/ml final concentration and after 2 h, cells were trypsinized, washed in PBS, the pellet was resuspended in hypotonic solution (0.075 M KCl) and incubated for 25 min at 37°C. Cells were then washed three times with methanol:acetic acid (4:1) and the cell suspension was dropped on microscope slides and Giemsa stained. Twenty metaphase cells from each DEB concentration were scored for chromosome breakage after image capture using the Metafer Slide Scanning Platform from Metasystems (45).

Supplementary Material

Funding

This study was partially supported by funds from ‘Ricerca Finalizzata – Bando 2010’ from Ministero della Salute, Italy, to P.P. and C.T., Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC-IG 12821) to P.P., (IG 12780) to L.O., (IG 5706) to L.V., and (“5xmille” n. 12237) to A.F., Italian citizens who allocated a 5/1000 share of their tax payment in support of the Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale Tumori to S.M. and P.R., of the CRO Aviano National Cancer Institute to A.V. and of the Istituto Oncologico Veneto IOV – IRCCS to M.M., according to Italian law and Fondazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro’ (FIRC)—triennial fellowship ‘Armanda e Enrivo Mirto’ to I.C. and triennial fellowship ‘Mario e Valeria Rindi’ to V.S.; National Institutes of Health (NIH, CA128978, CA116167 and CA176785) and the Breast Cancer Research Foundation to F.J.C.; Spanish Network on Rare Diseases (CIBERER) and the PI12/00070; the Spanish Carlos III Health Institute (FIS project PI12/02585) to O.D.; Asociación Española Contra el Cáncer, Spanish Health Research Foundation, Ramón Areces Foundation, Catalan Health Institute and Autonomous Government of Catalonia (ISCIIIRETIC RD12/0036/008, PI10/01422, PI12/01528, PI13/00285, 2009SGR290 and 2009SGR283); the Swedish Cancer Society, Berta Kamprad Foundation, Gunnar Nilsson Foundation, BioCARE and the Swedish Society of Medicine; UNICANCER, the Ligue Nationale Contre le Cancer and the French National Institute of Cancer (INCa); MINECO (SAF2012-31881), ICREA Academia, Generalitat de Catalunya (SGR0489-2009, SGR317-2014) and European Regional Development FEDER Funds to J.S.; Canadian Breast Cancer Foundation, Canadian Foundation for Innovation, Canada Research Chairs Secretariat and the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC Discovery Grant 371758-2009) to P.K.R.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all the individuals who took part in this study. We also wish to thank Antonis Antoniou (University of Cambridge) for helpful discussion, Claudia Foglia (INT) for DNA preparation, Fernando Ravagnani (INT) for recruitment of blood donors and Donata Penso (INT) for cell lines authentication; Roser Pujol and Maria Jose Ramirez (CIBERER/UAB) for cytogenetic analysis; Victoria Fernandez (CNIO) for the genotyping study; Gabriel Capella (Hereditary Cancer Program ICO) for the clinical and molecular work done in identifying and genotyping breast cancer patients; Peter Bugert (University of Heidelberg) for collecting control samples; Rongxi Yang and Katharina Mattes for supporting the genotyping; all the collaborating cancer clinics of the French National Study GENESIS (GENE SISters), M. Marcou, D. Le Gal, L. Toulemonde, J. Beauvallet, N. Mebirouk, E. Cavaciuti, A. Fescia (genetic epidemiology platform The PIGE, Plateforme d'Investigation en Génétique et Epidemiologie), C. Verny-Pierre and L. Barjhoux (Biological Resource Centre); H. te Riele and N. Ameziane for sharing materials; all the collaborating centers of the Swedish national study SWEA (SWE-BRCA Extended Analysis).

Conflict of Interest statement. P.K.R. is the inventor of US Patent 5,867,402 and other patents pending, which predict and validate mutations. He is one of the founders of Cytognomix, Inc. (London, Canada), which creates software based on this technology. All the others authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Ferlay J., Shin H.R., Bray F., Forman D., Mathers C., Parkin D.M. (2010) Estimates of worldwide burden of cancer in 2008: GLOBOCAN 2008. Int. J. Cancer, 127, 2893–2917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collaborative Group on Hormonal Factors in Breast Cancer. (2001) Familial breast cancer: collaborative reanalysis of individual data from 52 epidemiological studies including 58,209 women with breast cancer and 101,986 women without the disease. Lancet, 358, 1389–1399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mavaddat N., Antoniou A.C., Easton D.F., Garcia-Closas M. (2010) Genetic susceptibility to breast cancer. Mol. Oncol., 4, 174–191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Michailidou K., Beesley J., Lindstrom S., Canisius S., Dennis J., Lush M.J., Maranian M.J., Bolla M.K., Wang Q., Shah M. et al. (2015) Genome-wide association analysis of more than 120,000 individuals identifies 15 new susceptibility loci for breast cancer. Nat. Genet., 47, 373–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Renwick A., Thompson D., Seal S., Kelly P., Chagtai T., Ahmed M., North B., Jayatilake H., Barfoot R., Spanova K. et al. (2006) ATM mutations that cause ataxia-telangiectasia are breast cancer susceptibility alleles. Nat. Genet., 38, 873–875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rahman N., Seal S., Thompson D., Kelly P., Renwick A., Elliott A., Reid S., Spanova K., Barfoot R., Chagtai T. et al. (2007) PALB2, which encodes a BRCA2-interacting protein, is a breast cancer susceptibility gene. Nat. Genet., 39, 165–167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meindl A., Hellebrand H., Wiek C., Erven V., Wappenschmidt B., Niederacher D., Freund M., Lichtner P., Hartmann L., Schaal H. et al. (2010) Germline mutations in breast and ovarian cancer pedigrees establish RAD51C as a human cancer susceptibility gene. Nat. Genet., 42, 410–414. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Le Calvez-Kelm F., Lesueur F., Damiola F., Vallee M., Voegele C., Babikyan D., Durand G., Forey N., McKay-Chopin S., Robinot N. et al. (2011) Rare, evolutionarily unlikely missense substitutions in CHEK2 contribute to breast cancer susceptibility: results from a breast cancer family registry case-control mutation-screening study. Breast Cancer Res., 13, R6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weischer M., Bojesen S.E., Ellervik C., Tybjaerg-Hansen A., Nordestgaard B.G. (2008) CHEK2*1100delC genotyping for clinical assessment of breast cancer risk: meta-analyses of 26,000 patient cases and 27,000 controls. J. Clin. Oncol., 26, 542–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Park D.J., Lesueur F., Nguyen-Dumont T., Pertesi M., Odefrey F., Hammet F., Neuhausen S.L., John E.M., Andrulis I.L., Terry M.B. et al. (2012) Rare mutations in XRCC2 increase the risk of breast cancer. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 90, 734–739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hilbers F.S., Wijnen J.T., Hoogerbrugge N., Oosterwijk J.C., Collee M.J., Peterlongo P., Radice P., Manoukian S., Feroce I., Capra F. et al. (2012) Rare variants in XRCC2 as breast cancer susceptibility alleles. J. Med. Genet., 49, 618–620. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Thompson E.R., Doyle M.A., Ryland G.L., Rowley S.M., Choong D.Y., Tothill R.W., Thorne H., Barnes D.R., Li J., Ellul J. et al. (2012) Exome sequencing identifies rare deleterious mutations in DNA repair genes FANCC and BLM as potential breast cancer susceptibility alleles. PLoS Genet., 8, e1002894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ellis N.A., Offit K. (2012) Heterozygous mutations in DNA repair genes and hereditary breast cancer: a question of power. PLoS Genet., 8, e1003008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bakker J.L., van Mil S.E., Crossan G., Sabbaghian N., De Leeneer K., Poppe B., Adank M., Gille H., Verheul H., Meijers-Heijboer H. et al. (2013) Analysis of the novel fanconi anemia gene SLX4/FANCP in familial breast cancer cases. Hum. Mutat., 34, 70–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.de Garibay G.R., Diaz A., Gavina B., Romero A., Garre P., Vega A., Blanco A., Tosar A., Diez O., Perez-Segura P. et al. (2013) Low prevalence of SLX4 loss-of-function mutations in non-BRCA1/2 breast and/or ovarian cancer families. Eur. J. Hum. Genet., 21, 883–886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shah S., Kim Y., Ostrovnaya I., Murali R., Schrader K.A., Lach F.P., Sarrel K., Rau-Murthy R., Hansen N., Zhang L. et al. (2013) Assessment of SLX4 mutations in hereditary breast cancers. PLoS One, 8, e66961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gracia-Aznarez F.J., Fernandez V., Pita G., Peterlongo P., Dominguez O., de la Hoya M., Duran M., Osorio A., Moreno L., Gonzalez-Neira A. et al. (2013) Whole exome sequencing suggests much of non-BRCA1/BRCA2 familial breast cancer is due to moderate and low penetrance susceptibility alleles. PLoS One, 8, e55681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang G.S., Cooper T.A. (2007) Splicing in disease: disruption of the splicing code and the decoding machinery. Nat. Rev. Genet., 8, 749–761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sterne-Weiler T., Howard J., Mort M., Cooper D.N., Sanford J.R. (2011) Loss of exon identity is a common mechanism of human inherited disease. Genome Res., 21, 1563–1571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mucaki E.J., Shirley B.C., Rogan P.K. (2013) Prediction of mutant mRNA splice isoforms by information theory-based exon definition. Hum. Mutat., 34, 557–565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Caceres J.F., Stamm S., Helfman D.M., Krainer A.R. (1994) Regulation of alternative splicing in vivo by overexpression of antagonistic splicing factors. Science, 265, 1706–1709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meetei A.R., Medhurst A.L., Ling C., Xue Y., Singh T.R., Bier P., Steltenpool J., Stone S., Dokal I., Mathew C.G. et al. (2005) A human ortholog of archaeal DNA repair protein Hef is defective in Fanconi anemia complementation group M. Nat. Genet., 37, 958–963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kiiski J.I., Pelttari L.M., Khan S., Freysteinsdottir E.S., Reynisdottir I., Hart S.N., Shimelis H., Vilske S., Kallioniemi A., Schleutker J. et al. (2014) Exome sequencing identifies FANCM as a susceptibility gene for triple-negative breast cancer. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA, 111, 15172–15177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kottemann M.C., Smogorzewska A. (2013) Fanconi anaemia and the repair of Watson and Crick DNA crosslinks. Nature, 493, 356–363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tischkowitz M., Xia B. (2010) PALB2/FANCN: recombining cancer and Fanconi anemia. Cancer Res., 70, 7353–7359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Walden H., Deans A.J. (2014) The Fanconi anemia DNA repair pathway: structural and functional insights into a complex disorder. Annu. Rev. Biophys., 43, 257–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Huang J., Liu S., Bellani M.A., Thazhathveetil A.K., Ling C., de Winter J.P., Wang Y., Wang W., Seidman M.M. (2013) The DNA translocase FANCM/MHF promotes replication traverse of DNA interstrand crosslinks. Mol. Cell, 52, 434–446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Antoniou A.C., Casadei S., Heikkinen T., Barrowdale D., Pylkas K., Roberts J., Lee A., Subramanian D., De Leeneer K., Fostira F. et al. (2014) Breast-cancer risk in families with mutations in PALB2. N. Engl. J. Med., 371, 497–506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sawyer S.L., Tian L., Kähkönen M., Schwartzentruber J., Kircher M.; University of Washington Centre for Mendelian Genomics; FORGE Canada Consortium, Majewski J., Dyment D.A., Innes A.M. et al. (2015) Biallelic mutations in BRCA1 cause a new Fanconi anemia subtype. Cancer Discov., 5, 135–142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Singh T.R., Bakker S.T., Agarwal S., Jansen M., Grassman E., Godthelp B.C., Ali A.M., Du C.H., Rooimans M.A., Fan Q. et al. (2009) Impaired FANCD2 monoubiquitination and hypersensitivity to camptothecin uniquely characterize Fanconi anemia complementation group M. Blood, 114, 174–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lim E.T., Würtz P., Havulinna A.S., Palta P., Tukiainen T., Rehnström K., Esko T., Mägi R., Inouye M., Lappalainen T. et al. (2014) Distribution and medical impact of loss-of-function variants in the Finnish founder population. PLoS Genet., 10, e1004494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Southey M.C., Park D.J., Nguyen-Dumont T., Campbell I., Thompson E., Trainer A.H., Chenevix-Trench G., Simard J., Dumont M., Soucy P. et al. (2013) COMPLEXO: identifying the missing heritability of breast cancer via next generation collaboration. Breast Cancer Res., 15, 402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hosmer D.W., Lemeshow S. (1989) Applied Logistic Regression. John Wiley & Sons, New York, USA. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Normand S.L. (1999) Tutorial in biostatistics. Meta-analysis: formulating, evaluating, combining and reporting. Stat. Med., 18, 321–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mehta C.R., Patel N., Senchaudhuri P. (2000) Efficient Monte Carlo methods for conditional logistic regression. J. Am. Stat. Assoc., 95, 99–108. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huelga S.C., Vu A.Q., Arnold J.D., Liang T.Y., Liu P.P., Yan B.Y., Donohue J.P., Shiue L., Hoon S., Brenner S. et al. (2012) Integrative genome-wide analysis reveals cooperative regulation of alternative splicing by hnRNP proteins. Cell Rep., 1, 167–178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bi C., Rogan P.K. (2004) Bipartite pattern discovery by entropy minimization-based multiple local alignment. Nucleic Acids Res., 32, 4979–4991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Olsen R.K., Broner S., Sabaratnam R., Doktor T.K., Andersen H.S., Bruun G.H., Gahrn B., Stenbroen V., Olpin S.E., Dobbie A. et al. (2014) The ETFDH c.158A>G variation disrupts the balanced interplay of ESE- and ESS-binding proteins thereby causing missplicing and multiple Acyl-CoA dehydrogenation deficiency. Hum. Mutat., 35, 86–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Fackenthal J.D., Cartegni L., Krainer A.R., Olopade O.I. (2002) BRCA2 T2722R is a deleterious allele that causes exon skipping. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 71, 625–631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bruun G.H., Doktor T.K., Andresen B.S. (2013) A synonymous polymorphic variation in ACADM exon 11 affects splicing efficiency and may affect fatty acid oxidation. Mol. Genet. Metab., 110, 122–128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pastor T., Pagani F. (2011) Interaction of hnRNPA1/A2 and DAZAP1 with an Alu-derived intronic splicing enhancer regulates ATM aberrant splicing. PLoS One, 6, e23349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Colombo M., De Vecchi G., Caleca L., Foglia C., Ripamonti C.B., Ficarazzi F., Barile M., Varesco L., Peissel B., Manoukian S. et al. (2013) Comparative in vitro and in silico analyses of variants in splicing regions of BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes and characterization of novel pathogenic mutations. PLoS One, 8, e57173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bakker S.T., van de Vrugt H.J., Rooimans M.A., Oostra A.B., Steltenpool J., Delzenne-Goette E., van der Wal A., van der Valk M., Joenje H., te Riele H. et al. (2009) Fancm-deficient mice reveal unique features of Fanconi anemia complementation group M. Hum. Mol. Genet., 18, 3484–3495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bogliolo M., Schuster B., Stoepker C., Derkunt B., Su Y., Raams A., Trujillo J.P., Minguillon J., Ramirez M.J., Pujol R. et al. (2013) Mutations in ERCC4, encoding the DNA-repair endonuclease XPF, cause Fanconi anemia. Am. J. Hum. Genet., 92, 800–806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Castella M., Pujol R., Callen E., Trujillo J.P., Casado J.A., Gille H., Lach F.P., Auerbach A.D., Schindler D., Benitez J. et al. (2011) Origin, functional role, and clinical impact of Fanconi anemia FANCA mutations. Blood, 117, 3759–3769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.