Abstract

Eosinophilic gastroenteritis is a rare disease of unknown aetiology, characterised by eosinophilic infiltration of the gastrointestinal wall with various gastrointestinal manifestations. Clinical presentation and radiological findings are non-specific and there is an overlap with more frequent childhood diseases requiring a high degree of clinical suspicion for accurate diagnosis. We describe a 2-month-old boy with prolonged diarrhoea, vomiting and food refusal. Diagnosis was settled by histology. The treatment with elemental diet was successful, with clinical resolution and catch-up growth.

Background

Eosinophilic gastroenteritis (EGE) is a rare gastrointestinal disease that can present with various gastrointestinal manifestations.1 The aetiology of the disease remains unknown.2

EGE occurs over a wide age range, from infancy through the seventh decade, but most commonly between third to fifth decades of life.3 4 There is a slight male predominance, and it is reported to be more common in Caucasians.2–4 Its incidence is difficult to estimate owing to the rarity of the disease. Since the very first description of this disease by Kaijser,5 more than 300 cases have been reported in the medical literature, with very few cases in paediatric age, especially under 6 months.2 6

The diagnosis depends on the presence of gastrointestinal symptoms, the histological demonstration of the eosinophilic infiltration in one or more areas of the gastrointestinal tract, the absence of an underlying cause of eosinophilia and the exclusion of eosinophilic involvement in organs other than the gastrointestinal (GI) tract.2 4

Case presentation

We present the case of a previously healthy 2-month-old Caucasian boy who presented to the emergency department with a history of vomiting, diarrhoea (about 2 episodes after each meal, with no blood or mucous in the faeces) and food refusal of 2 days duration. Clinical examination was unremarkable except for signs of slight dehydration. He had a history of exclusive breast feeding until 1 month and 5 days prior, after which his feeding was supplemented with formula.

Laboratory tests on admission showed normal white cell count, with normal eosinophils. The infant underwent urine analysis, blood culture, parasitological and virological examination, and bacterial culture of stool, which were all negative.

Because of the persistence of diarrhoea with frequent liquid stools, food refusal and persistent weight loss, the infant's mother started him on a diet with restriction of cow milk; he was started on a semi-elemental diet on the eighth day of the disease and was submitted to further study, namely, specific IgE for cow's milk protein allergy and sweat test, which were negative; immunological and endocrinological studies were normal (table 1).

Table 1.

Results of immunological and endocrinological studies

| Study | Value (Reference value) |

|---|---|

| IgG | 382 mg/dL (N: 230–663) |

| IgA | 59.7 mg/dL (N: 5–48) |

| IgM | 108 mg/dL (N:8–57) |

| IgE | 8.13 IKU/L |

| IgE lactoalbumin specific | 0.05 UK/L (class 0) |

| IgE lactoglobulin specific | 0.15 UK/L (class 0) |

| IgE casein specific | 0.07 UK/L (class 0) |

| C3 | 82.2 mg/dL (N: 75–135) |

| C4 | 26.1 mg/dL (N: 9–36) |

| Cortisol | 9.6 mg/dL (N: 6.2–19.4) |

| 17-α-OH-progesterone | 3.40 ng/mL (N: 0.59–3.44) |

| δ-4-androstenedione | 1.80 ng/mL (N: 0.30–2.63) |

| Dehydroepiandrostenedione-sulfate | 26.26 µg/dL (N: 3.4–124) |

| Parathormone | 13.9 pg/mL (N: 15–65) |

| T4 | 8.87 µg/dL (N: 5.1–14.1) |

| TSH | 1.16 µUI/mL (N: 0.27–4.2) |

| Total testosterone | 0.27 ng/mL (N: 0.12–0.21) |

TSH, thyroid-stimulating hormone.

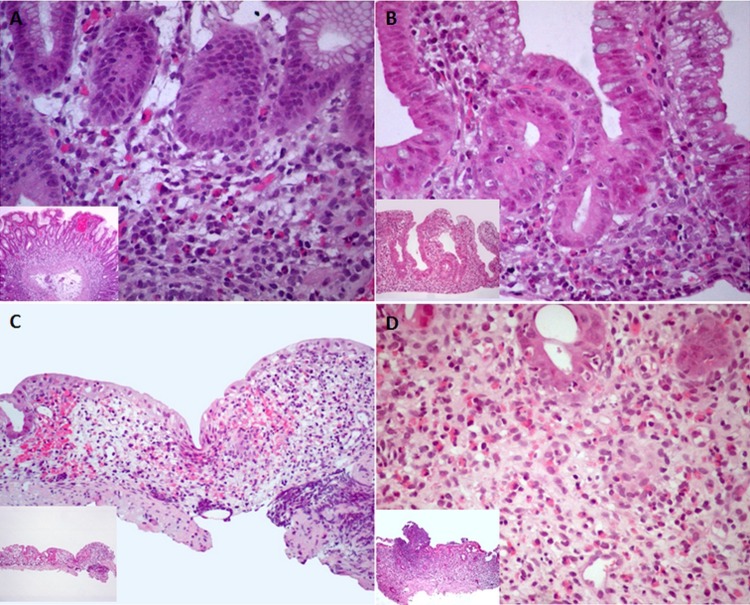

Twenty days after the beginning of symptoms, significant weight had been lost (5% less than on admission), and the patient was submitted to upper endoscopy and colonoscopy with progression to 25 cm from the anus. At endoscopy, the appearance of the mucosa was normal, except for punctiform erythema in the 5 cm of distal mucosa of the rectum. The infant was started on an elemental diet with favourable clinical course and weight recovery (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Clinical evolution reporting weight and its correlation with principal treatments.

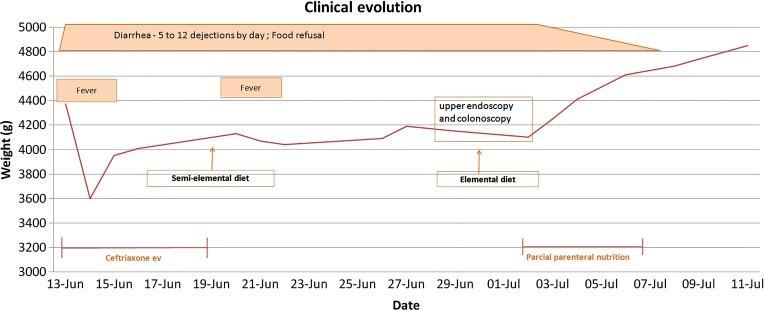

Subsequently, the histological examination revealed an inflammatory process with heavy infiltration of eosinophils, with a count of eosinophils of over 50 per high-power field (figure 2) in the stomach, duodenum, colon and rectum, confirming a diagnosis of EGE. An elemental diet, the single treatment used, afforded good weight progression (P50).

Figure 2.

Eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Histopathology of gastric mucosa (A), duodenum (B), colon (C) and rectum (D) showing dense eosinophilic infiltrate in the lamina propria (eosinophils are over E 50 per high-power field). Eosinophils permeate the epithelium of the crypts (D) (H&E stain; magnification ×400 and ×100 (inset)).

Outcome and follow-up

The child was regularly followed in paediatric gastroenterology consultation. By the fifth month, a tolerance test with hydrolysed milk protein was performed, with recurrence of diarrhoea. Other food (cereals, fruit, meat, fish and egg) was gradually introduced with good tolerance. Under medical care, tolerance tests were performed with hydrolysed milk protein (12 months), soy milk protein (18 months) and cow milk protein (24 months). There were no complications and the child maintained good weight progression at P50.

Discussion

EGE in children is a rare disease characterised by intensive infiltration of eosinophils of one or more organs of the GI tract.4 The aetiology and pathogenesis are not well understood and mostly based on case reports.2 Many patients have a history of atopy and elevated serum IgE levels, strongly suggesting the role of hypersensitivity reactions in its pathogenesis.2 6 7

According to the literature, the stomach is the organ most commonly affected, followed by the small intestine and the colon.2 The anatomical locations of eosinophilic infiltrates and the depth of GI involvement determine clinical symptoms.3 EGE can be classified into mucosal, muscular and serosal types.8 The mucosal form, which is more common (25–100%), usually presents as abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, dyspepsia, diarrhoea, malabsorption, gastrointestinal haemorrhage, protein-losing enteropathy and weight loss.2 Children and adolescents can present with growth retardation and failure to thrive.1 The muscular form (10–60%) typically presents with pyloric or intestinal obstruction. The subserosal form, which is less common, usually presents with exudative ascites.2

The currently accepted criteria are the presence of gastrointestinal symptoms, a predominant eosinophilic infiltrate on the histological examination and the exclusion of other causes of eosinophilia.1 6 A cut-off of 20–50 eosinophils per high-power field has been indicated as a diagnostic criterion by some authors.1 2 8

Endoscopy, CT scan and ultrasonography may provide important indirect signs of the disease.1 The endoscopic appearance is non-specific and usually reveals erythematous, friable, sometimes nodular mucosa, and is rarely ulcerated.2 6 Because of the mucosal sparing observed in some cases, multiple biopsies should be taken from different areas.1 7 Laboratory findings that support the diagnosis of EGE include, but are not limited to, peripheral eosinophilia (ranging from 5 to 70%), hypoalbuminaemia, abnormal D-xylose test, increased faecal fat, iron deficiency anaemia and elevated serum IgE levels. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate is rarely elevated.2 8 The differential diagnoses include intestinal parasitic infections, primary hypereosinophilic syndrome, malignancies (gastric cancer, lymphoma) and the vasculitic phase of Churg-Strauss syndrome.2

When the disease manifests in infancy and specific food sensitisation can be identified, the likelihood of disease remission by late childhood is high.3

There is no consensus about the treatment of EGE, and few studies have been made; treatment experience in paediatrics is scanty. Owing to the evident association with allergy, a careful search of inciting food allergens and a medication review should be performed, and care should be taken to avoid contact with putative triggers of the disease.2 The results from the elimination diets are variable, but complete resolution is generally achieved with amino acid elemental diets.9 When the improvement of the symptoms with the diet restriction is poor or not feasible, the next step in the treatment is the use of steroids.1 Among other medications, mast cell stabilisers, antihistaminic drugs and a selective leucotriene receptor antagonist (montelukast) have shown favourable results in some patients.2 7

Learning points.

Eosinophilic gastroenteritis diagnosis in this young infant was possible due to a high index of suspicion with an early endoscopic and histologic examination and provided an attempted treatment.

This rare entity should be suspected in children with chronic diarrhea and failure to thrive, even without peripheral eosinophilia.

A late diagnosis may have serious consequences for growth, particularly in paediatric age.

Footnotes

Contributors: The authors hope to alert clinicians to a rare entity in infancy that may be the cause of digestive symptoms and failure to thrive. This diagnosis may be suspected even in children a few months of age. Because the diagnosis is difficult and laboratory tests may be normal, it is necessary to be aware of this pathology to perform an endoscopic examination, even at such a young age.

Competing interests: None declared.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Agrawal N, Rani KU, Sridhar R et al. . Eosinophilic gastroenteritis: a diagnosis behind the curtains. J Clin Diagn Res 2012;6:1789–90. 10.7860/JCDR/2012/4650.2615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mori A, Enweluzo C, Grier D et al. . Eosinophilic gastroenteritis: review of a rare and treatable disease of the gastrointestinal tract. Case Report Gastroenterol 2013;7:293–8. 10.1159/000354147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ingle SB, Hinge CR. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis: an unusual type of gastroenteritis. World J Gastroenterol 2013;19:5061–6. 10.3748/wjg.v19.i31.5061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelly KJ. Eosinophilic gastroenteritis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2000;30:28–35. 10.1097/00005176-200001001-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaijser R. Zur Kenntnis der allergischen affektionen des verdauungskanals vom standput des chirurgen aus. Arch Klin Chir 1937;188:36–64. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sheikh RA, Prindiville TP, Pecha RE et al. . Unusual presentations of eosinophilic gastroenteritis: case series and review of literature. World J Gastroenterol 2009;15:2156–61. 10.3748/wjg.15.2156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Temiz T, Yaylaci S, Demir MV et al. . Eosinophilic gastroenteritis: a rare case report. N Am J Med Sci 2012;4:367–8. 10.4103/1947-2714.99522 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Klein N, Hargrove R, Sleisenger M et al. . Eosinophilic gastroenteritis. Medicine (Baltimore) 1970;49:299–319. 10.1097/00005792-197007000-00003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chehade M, Magid MS, Mofidi S et al. . Aullergic eosinophilic gastroenteritis with protein-losing enteropathy: intestinal pathology, clinical course, and long-term follow-up. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr 2006;42:516–21. 10.1097/01.mpg.0000221903.61157.4e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]