Abstract

To investigate the associations between psychosocial factors and the development of chronic disabling low back pain (LBP) in Japanese workers. A 1 yr prospective cohort of the Japan Epidemiological Research of Occupation-related Back Pain (JOB) study was used. The participants were office workers, nurses, sales/marketing personnel, and manufacturing engineers. Self-administered questionnaires were distributed twice: at baseline and 1 yr after baseline. The outcome of interest was the development of chronic disabling LBP during the 1 yr follow-up period. Incidence was calculated for the participants who experienced disabling LBP during the month prior to baseline. Logistic regression was used to assess risk factors for chronic disabling LBP. Of 5,310 participants responding at baseline (response rate: 86.5%), 3,811 completed the questionnaire at follow-up. Among 171 eligible participants who experienced disabling back pain during the month prior to baseline, 29 (17.0%) developed chronic disabling LBP during the follow-up period. Multivariate logistic regression analysis implied reward to work (not feeling rewarded, OR: 3.62, 95%CI: 1.17–11.19), anxiety (anxious, OR: 2.89, 95%CI: 0.97–8.57), and daily-life satisfaction (not satisfied, ORs: 4.14, 95%CI: 1.18–14.58) were significant. Psychosocial factors are key to the development of chronic disabling LBP in Japanese workers. Psychosocial interventions may reduce the impact of LBP in the workplace.

Keywords: Chronic disabling low back pain, Nonspecific low back pain, Psychosocial factors, Risk factors, Japanese workers

Introduction

Individuals commonly experience low back pain (LBP) at some stage during their life. Most LBP cases are classified as non-specific1), which is not attributable to any identifiable pathology in the spine2). It is well-acknowledged that those who had LBP once tend to have subsequent episodes within a year3,4,5,6), while each LBP episode can be resolved within a few weeks to 3 months7, 8). Despite the resolving nature of LBP, a small proportion of individuals with LBP (2–7%) develop chronic pain8) which persists for 12 wk or longer2). In fact, LBP was found to be the leading specific cause of years lived with disability9). Not surprisingly, Western research has indicated that LBP, especially chronic LBP entailing disability, accounts for substantial economic loss at the workplace as well as in the healthcare system2, 10).

An earlier Japanese study reported a lifetime LBP prevalence of over 80%11). Not surprisingly, the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare of Japan (MHLW) reported that LBP is the first and second most common health complaint in 2013 among Japanese men and women, respectively12). Since LBP is common in the Japanese population, the economic loss caused at the workplace and in the healthcare system is presumably as large as in Western countries.

In previous research, individual factors as well as ergonomic factors related to work have been well-investigated. In recent decades, an increasing body of evidence, however, has revealed that psychosocial factors play an important role in chronic non-specific LBP. In particular, distress (i.e., psychological distress, depressive mood, and depressive symptoms)13, 14), low job satisfaction14,15,16), emotional trauma in childhood such as abuse17), and pain level18) affect the development of chronic LBP.

Although the proportion of individuals suffering from chronic LBP is small according to Western studies, it is important to identify potential risk factors since the small proportion accounts for large loss. Little, however, is known concerning chronic disabling LBP in relation to psychosocial factors in Japanese workers. The objective of the present study was to investigate the associations between psychosocial factors and the development of chronic disabling LBP in Japanese workers.

Subjects and Methods

Data source

Data were drawn from a 1-yr prospective cohort of the Japan Epidemiological Research of Occupation-related Back Pain (JOB) study. Ethical approval was obtained from the review board of the MLHW. Participants for the JOB study were recruited at 16 local offices of the participating organizations in or near Tokyo. The occupations of the participating workers were diverse (e.g., office workers, nurses, sales/marketing personnel, and manufacturing engineers). Baseline questionnaires were distributed to employees by the board of each participating organization. Participants provided written informed consent and returned completed self-administered questionnaires with their name and mailing address for the purpose of follow-up directly to the study administration office. At a year after the baseline assessment, the follow-up questionnaire was distributed to the participants.

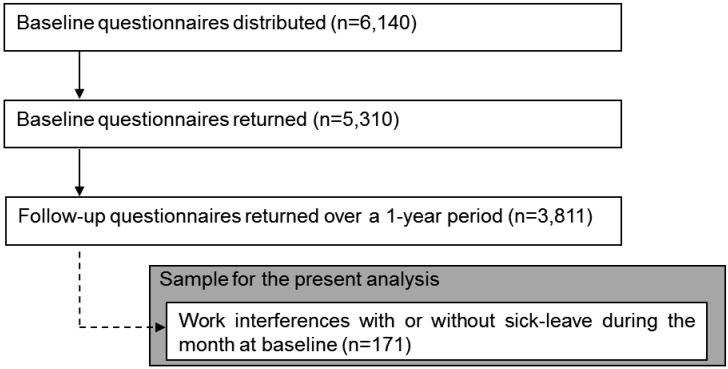

The baseline questionnaires contained questions on the presence of LBP, severity of LBP, individual characteristics (e.g., gender, age, obesity, smoking habit), ergonomic work demands (e.g., manual handling at work, frequency of bending, twisting), and work-related psychosocial factors (e.g., interpersonal stress at work, job control, reward to work, depression, somatization). LBP was defined in the questionnaire as pain localized between the costal margin and the inferior gluteal folds10). A diagram showing these areas was provided in the questionnaire to facilitate workers’ understanding of the LBP area (Fig. 1). To evaluate the severity of LBP, Von Korff’s grading19) was used in the following manner: grade 0 was defined as no LBP; grade 1 as LBP that does not interfere with work; grade 2 as LBP that interferes with work but no absence from work; and grade 3 as LBP that interferes with work, leading to sick-leave. For the assessment of the psychosocial factors, the Brief Job Stress Questionnaire (BJSQ) developed by the MLHW20, 21) was used. The BJSQ contains 57 questions and assesses 19 work-related stress factors: mental workload both quantitative- and qualitative-wise, physical workload, interpersonal stress at work, workplace environment stress, job control, utilization of skills and expertise, job fitness, reward to work, vigor, anger, fatigue, anxiety, depressed mood, somatic symptoms, supports by supervisors, supports by coworkers, supports by family or friends, and daily-life (work and life) satisfaction. These work-related factors were rated on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from the lowest score of 1 to the highest of 5.

Fig. 1.

Diagram showing pain area for low back provided in the baseline and follow-up questionnaires.

The BJSQ incorporates questions from various standard questionnaires such as the Job Content Questionnaire (JCQ)22), the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH)23), the Profile of Mood States (POMS)24), the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D)25), the State-trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI)26), the Screener for Somatoform Disorders (SSD)27) and the Subjective Well-being Inventory (SUBI)28). Standardized scores were developed for the 19 individual factors based on the sample of approximately 10,000 Japanese workers. The BJSQ has been shown to have internal consistency reliability and criterion validity with respect to the JCQ and NIOSH29).

The follow-up questionnaire contained questions about the severity of LBP during the previous year, length of sick-leave because of LBP, medical care seeking, pain duration, and onset pattern. LBP severity was assessed using Von Korff’s grading in the same manner as baseline.

Data analysis

The outcome of our interest was the development of chronic disabling LBP during the 1-yr follow-up period. In the present study, chronic disabling LBP was defined if a participant experienced LBP that interfered with work, with or without sick-leave due to LBP, corresponding to grade 2 or 3 in Von Korff’s grading, during the month prior to baseline and experienced LBP with the same grades for 3 months or longer during the 1-yr follow-up period. Absence from work is often used as the outcome measurement for disability in Western studies. The present study, however, defined chronic disabling LBP as LBP that interfered with work for 3 months or longer, regardless of sick leave because our early international epidemiological study indicated that the proportion of Japanese workers who both took time off work and did not due to musculoskeletal disorders is almost equal to that of British workers who took time off work from the same reason30). This finding may be a result of cultural differences in attitude toward one’s work. For this reason, the present study defined chronic disabling LBP as LBP that interfered with work for 3 months or longer, regardless of sick leave.

Incidence was calculated for the participants who experienced disabling LBP (grade 2 or 3) during the month prior to the baseline survey. Participants were excluded from the analysis if they changed their job for reasons other than LBP or developed LBP due to accident, a tumor, including metastasis, infection, or fracture.

For data analysis, the following factors were initially included: (1) individual characteristics, (2) ergonomic work demands, and (3) work-related psychosocial factors. Individual characteristics included age, sex, obesity (body mass index: BMI ≥25 kg/m2), smoking habit (Brinkman index ≥400), education, flexibility, hours of sleep, experience at current job, working hours per wk (≥60 h per week of uncontrolled overtime), work shift, emotional trauma in childhood, and pain level (NRS ≥8 as painful). Ergonomic work demands included manual handling at work; bending, twisting (≥half of the day as frequent); and hours of desk work (≥half of the day as frequent). Psychosocial factors were assessed with BJSQ. The 5-point Likert scale was reclassified into 2 categories: the “not feeling stressed” category, where low, slightly low, and moderate were combined, and the “feeling stressed” category, where slightly high and high were combined. Pain level was scaled on the Numerical Rating Scale, ranging from 0 to 11.

To assess smoking habit, the Brinkman Index was calculated based on the total number of cigarettes smoked per day multiplied by duration of smoking in year31). A Brinkman Index value of 400 or higher indicated that a respondent was a heavy smoker, whereas a value of less than 400 indicated that a respondent was a non-heavy smoker. Workers were defined as flexible if their wrists could reach beyond their knees but without their fingertips touching their ankles, and not flexible if their wrists could not reach beyond their knees32).

In addition to descriptive statistics, univariate and multivariate logistic regression analyses were conducted to examine the associations between risk factors and the development of chronic disabling LBP. Results of logistic regression analyses were summarized by odds ratios (ORs) and the respective 95% confidence intervals (CI). To assess potential risk factors, crude ORs were initially computed. Subsequently, all factors with p<0.1 in univariate logistic regression analyses were entered into the multivariate logistic regression model, significance levels of p<0.05 for entry and p>0.1 for removal. The stepwise method was used to select variables with statistical significance at p<0.05. All tests were 2-tailed. The software package STATA 9.0 (StataCorp, LP, College Station, TX) was used for all statistical analyses.

Results

Baseline characteristics of the follow-up vs. drop-out group

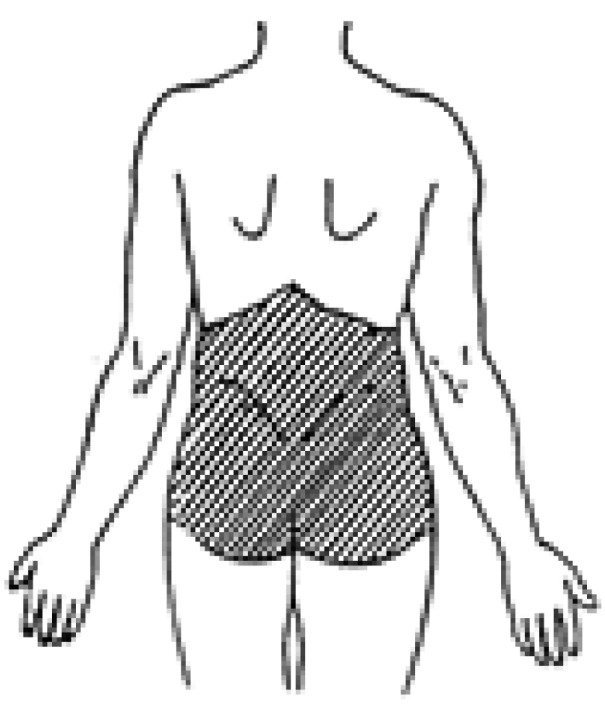

The baseline questionnaire was distributed to 6,140 workers and had a response rate of 86.5% (5,310 workers). Of these participants, 3,811 workers successfully completed and returned 1-yr follow-up questionnaires (follow-up rate: 71.8%).

The characteristics of the 3,811 participants who provided follow-up data (follow-up group) did not appear to be much different from those who did not (drop-out group). The mean [standard deviation (SD)] age of the follow-up group was 42.9 (10.1) yr, compared to 38.0 (10.2) yr in the drop-out group. The majority were men in both groups (80.6% and 82.8%, respectively). The mean (SD) BMI of the follow-up group and drop-out group were similar [23.1 (3.3) and 22.9 (4.1), respectively]. In the follow-up group, 78.6% of the participants engaged in the manual handling of objects <20 kg, or not manually handling any objects at work, 17.8% engaged in manually handling objects ≥20 kg or worked as a caregiver, and data was missing for 3.6%. The respective values for the drop-out group were 75.5%, 18.9%, and 5.6%. In both the follow-up and drop-out groups, the most common occupational fields were office workers engaging in the manual handling of objects <20 kg or not manually handling any objects and nurse engaging in manual handling of objects ≥20 kg or caregiver.

Baseline characteristics of the study participants

Of the 3,811 workers, 171 reported LBP and experiencing work interferences with or without sick-leave during a month prior to baseline (Fig. 2). The mean (SD) age of 171 participants was 41.5 (10.2) yr and the majority were men (n=122; 71.4%). The mean (SD) BMI of the participants was 23.0 (3.6; n=170) kg/m2. About half of the participants did not engage in manually handling heavy objects at work (n=79; 48.8%). Those workers who manually handled objects of less than 20 kg accounted for 17.9% (n=29) and those who manually handled heavy objects 20 kg or heavier or worked as a caregiver accounted for 33.3% (n=54). Desk work and sales, manufacturing, and nurses were the major occupations in the categories of non-manually handling work, manually handling work of less than 20 kg, and manually handling work of 20 kg or heavier, respectively.

Fig. 2.

Flow chart of the sample selection for the present analysis.

Incidence of chronic disabling LBP

Of a total of 171 eligible participants, 29 (17.0%) developed chronic disabling LBP during a year prior to the follow-up period (5 missing cases).

Association between chronic disabling LBP and potential risk factors

Crude and adjusted ORs for the development of chronic disabling LBP and their 95% CIs are shown in Tables 1 and 2. The univariate logistic regression analysis showed that job fitness, reward to work, vigor, anger, fatigue, anxiety, depressed mood, supports by supervisors, daily-life satisfaction, work shift, emotional trauma in childhood, and pain level were potentially associated with the development of chronic disabling LBP (ORs of 2.00–7.93; p<0.1 for all) (Table 1). In the multivariate logistic regression analysis, these 12 factors were entered into the model. As a result, 3 psychosocial factors were selected: reward to work (OR: 3.62, 95%CI: 1.17–11.19), anxiety (OR: 2.89, 95%CI: 0.97–8.57), and daily-life satisfaction (OR: 4.14, 95%CI: 1.18–14.58) (Table 2), indicating that a combination of psychosocial factors can play a key role in the development of chronic disabling LBP. A supplemental analysis was conducted to examine a combination effect of psychosocial factors: reward to work and daily-life satisfaction, which were at p<0.05 in the multiple logistic regression model (Table 3). Consequently, ORs increased with the level of dissatisfaction in a combination of daily-life satisfaction and reward to work. The results suggested that when both daily-life satisfaction and reward to work were not satisfied with an approximately 8-fold higher risk of developing chronic disabling LBP.

Table 1. Crude odds ratios of baseline factors for chronic disabling LBP.

| Risk factor | n | % | Odds ratio | 95%CI | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (yr) | 171 | |||||

| < 40 | 78 | 45.6 | 1.00 | |||

| 40–49 | 51 | 29.8 | 0.95 | 0.36–2.48 | 0.909 | |

| ≥ 50 | 42 | 24.6 | 1.17 | 0.44–3.12 | 0.746 | |

| Sex | 171 | |||||

| Male | 122 | 71.4 | 1.00 | |||

| Female | 49 | 28.7 | 1.26 | 0.53–3.03 | 0.601 | |

| Obesitya | 169 | |||||

| < BMI 25 kg/m2 | 129 | 76.3 | 1.00 | |||

| ≥ BMI 25 kg/m2 (obesity) | 40 | 23.7 | 0.85 | 0.32–2.28 | 0.748 | |

| Smoking habit | 153 | |||||

| Heavy smoker | 112 | 73.2 | 1.00 | |||

| Not heavy smoker | 41 | 26.8 | 1.80 | 0.72–4.52 | 0.211 | |

| Education | 165 | |||||

| College/Junior college | 105 | 63.6 | 1.00 | |||

| High school/Junior high school | 60 | 36.4 | 0.44 | 0.17–1.18 | 0.103 | |

| Flexibility | 162 | |||||

| Flexibility | 98 | 60.5 | 1.00 | |||

| Not flexible | 64 | 39.5 | 0.57 | 0.23–1.41 | 0.225 | |

| Manual handling at work | 162 | |||||

| No manual handling (desk work) | 79 | 48.8 | 1.00 | |||

| Manual handling of < 20-kg objects | 29 | 17.9 | 1.40 | 0.43–4.50 | 0.577 | |

| Manual handling of ≥ 20-kg objects or working as a caregiver | 54 | 33.3 | 1.84 | 0.72–4.72 | 0.203 | |

| Bending | 169 | |||||

| Not frequent | 121 | 71.6 | 1.00 | |||

| Frequent | 48 | 28.4 | 1.40 | 0.58–3.40 | 0.454 | |

| Twisting | 168 | |||||

| Not frequent | 140 | 83.3 | 1.00 | |||

| Frequent | 28 | 16.7 | 1.24 | 0.42–3.65 | 0.690 | |

| Hours of desk work | 167 | |||||

| Not frequent | 111 | 66.5 | 1.00 | |||

| Frequent | 56 | 33.5 | 0.74 | 0.30–1.81 | 0.510 | |

| Mental workload (quantitative aspect) | 170 | |||||

| Not stressed | 66 | 38.8 | 1.00 | |||

| Stressed | 104 | 61.2 | 1.08 | 0.47–2.46 | 0.859 | |

| Mental workload (qualitative aspect) | 170 | |||||

| Not stressed | 71 | 41.8 | 1.00 | |||

| Stressed | 99 | 58.2 | 0.63 | 0.28–1.42 | 0.267 | |

| Physical workload | 171 | |||||

| Not stressed | 75 | 43.9 | 1.00 | |||

| Stressed | 96 | 56.1 | 1.62 | 0.70–3.73 | 0.260 | |

| Interpersonal stress at work | 171 | |||||

| Not stressed | 118 | 69.0 | 1.00 | |||

| Stressed | 53 | 31.0 | 1.15 | 0.49–2.68 | 0.745 | |

| Workplace environment stress | 171 | |||||

| Not stressed | 102 | 59.7 | 1.00 | |||

| Stressed | 69 | 40.4 | 1.95 | 0.87–4.38 | 0.105 | |

| Job control | 169 | |||||

| Controlled | 4 | 32.0 | 1.00 | |||

| Not controlled | 115 | 68.1 | 1.81 | 0.69–4.79 | 0.230 | |

| Utilization of skills and expertise | 170 | |||||

| Utilization of skills and expertise | 131 | 77.1 | 1.00 | |||

| No utilization of skills and expertise | 9 | 22.9 | 1.59 | 0.66–3.85 | 0.304 | |

| Job fitness | 171 | |||||

| Feeling fit | 114 | 66.7 | 1.00 | |||

| Not feeling fit | 7 | 33.3 | 2.04 | 0.91–4.60 | 0.086 | |

| Reward to work | 171 | |||||

| Feel rewarded | 120 | 70.2 | 1.00 | |||

| Not feeling rewarded | 51 | 29.8 | 3.59 | 1.57–8.20 | 0.002 | |

| Vigor | 170 | |||||

| Vigorous | 123 | 72.4 | 1.00 | |||

| Not vigorous | 47 | 27.7 | 2.12 | 0.92–4.88 | 0.078 | |

| Anger | 170 | |||||

| Not angry | 75 | 44.1 | 1.00 | |||

| Angry | 95 | 55.9 | 2.79 | 1.12–6.97 | 0.028 | |

| Fatigue | 171 | |||||

| No fatigue | 69 | 40.4 | 1.00 | |||

| Fatigue | 102 | 59.7 | 2.45 | 0.98–6.11 | 0.055 | |

| Anxiety | 171 | |||||

| Not anxious | 95 | 55.6 | 1.00 | |||

| Anxious | 76 | 44.4 | 2.75 | 1.19–6.35 | 0.018 | |

| Depressed mood | 169 | |||||

| Not feeling depressed | 79 | 46.8 | 1.00 | |||

| Depressed | 90 | 53.3 | 2.16 | 0.92–5.08 | 0.078 | |

| Somatic symptoms | 168 | |||||

| Not somatic symptoms | 58 | 34.5 | 1.00 | |||

| Somatic symptoms | 110 | 65.5 | 1.81 | 0.72–4.55 | 0.206 | |

| Supports by supervisors | 167 | |||||

| Supported | 103 | 61.7 | 1.00 | |||

| Not supported | 64 | 38.3 | 2.00 | 0.88–4.55 | 0.098 | |

| Supports by coworkers | 168 | |||||

| Supported | 93 | 55.4 | 1.00 | |||

| Not supported | 75 | 44.6 | 0.97 | 0.43–2.18 | 0.946 | |

| Supports by family or friends | 169 | |||||

| Supported | 128 | 75.7 | 1.00 | |||

| Not supported | 41 | 24.3 | 1.13 | 0.44–2.90 | 0.801 | |

| Daily-life satisfaction | 171 | |||||

| Satisfied | 96 | 56.1 | 1.00 | |||

| Not satisfied | 75 | 43.9 | 4.98 | 1.99–12.47 | 0.001 | |

| Hours of sleep | 168 | |||||

| ≤ 5 h | 151 | 89.9 | 1.00 | |||

| > 5 h | 17 | 10.1 | 1.56 | 0.47–5.21 | 0.466 | |

| Experience of current job | 171 | |||||

| < 5 yr | 55 | 32.2 | 1.00 | |||

| ≥ 5 yr | 116 | 67.8 | 1.02 | 0.43–2.42 | 0.970 | |

| Working hours per wk | 171 | |||||

| < 60 h | 131 | 76.6 | 1.00 | |||

| ≥ 60 h | 40 | 23.4 | 0.63 | 0.22–1.78 | 0.385 | |

| Work shift | 171 | |||||

| Daytime shift | 115 | 67.3 | 1.00 | |||

| Nighttime shift | 56 | 32.8 | 2.90 | 1.28–6.58 | 0.011 | |

| Emotional trauma in childhood | 143 | |||||

| No | 136 | 95.1 | 1.00 | |||

| Yes | 7 | 4.9 | 7.93 | 1.64–38.26 | 0.010 | |

| Pain level | 155 | |||||

| Not painful (NRS > 8) | 140 | 90.3 | 1.00 | |||

| Painful (NRS ≤ 8) | 15 | 9.7 | 4.11 | 1.31–12.85 | 0.015 | |

LBP: low back pain; CI: confidence interval; BMI: body mass index; NRS: numerical rating scale

BMI ≥ 25 kg/m2 is defined as obesity in Japan

Table 2. Stepwise logistic regression results of baseline factors for chronic disabling LBP.

| Risk factor | Odds ratio | 95%CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reward to work | |||

| Feel rewarded | 1.00 | ||

| Not feeling rewarded | 3.62 | 1.17–11.2 | 0.025 |

| Anxiety | |||

| Not anxious | 1.00 | ||

| Anxious | 2.89 | 0.97–8.57 | 0.056 |

| Daily-life satisfaction | |||

| Satisfied | 1.00 | ||

| Not satisfied | 4.14 | 1.18–14.58 | 0.027 |

LBP: low back pain; CI: confidence interval; BMI: body mass index.

Table 3. Odds ratios for chronic disabling LBP in relation with a combination of daily-life satisfaction and reward to work.

| Risk factor | Chronic disabling LBP | Odds ratio | 95%CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Daily-life satisfaction | Reward to work | Yes (%) | No (%) | ||

| Satisfied | Feel rewarded | 6 (7.7%) | 72 (92.3%) | - | - |

| Not feeling rewarded | 1 (7.7%) | 12 (92.3%) | 1.00 | 0.11–9.06 | |

| Not satisfied | Feel rewarded | 7 (18.9%) | 30 (81.1%) | 2.80 | 0.87–9.03 |

| Not feeling rewarded | 15 (39.5%) | 23 (60.5%) | 7.83 | 2.72–22.52 | |

LBP: low back pain; CI: confidence interval.

Discussion

Results suggest that exposure to multiple psychosocial factors potentially predisposes the development of chronic disabling LBP in Japanese workers, especially office workers, nurses, sales/marketing personnel, and manufacturing engineers. Similarly, an increasing body of evidence, mostly in Western countries, has indicated that psychosocial factors affect the development of chronic disabling LBP13,14,15,16,17).

The present study suggests that exposure to not one, but a combination of psychosocial factors, such as daily-life satisfaction and reward to work, may trigger the development of chronic disabling LBP with an 8-fold increased risk, compared to those who were satisfied with psychosocial aspects. Given that daily-life satisfaction in the BJSQ consists of the extent of being content with not only life, but also work, the results in the present study are consistent with Western studies indicating that job dissatisfaction predisposes the development of chronic disabling LBP14,15,16, 33,34,35). Another psychosocial factor, reward to work, can also be considered to be relevant to the magnitude in job satisfaction. The association between chronic disabling LBP and a combination of such psychosocial factors may possibly be explained by dysfunction in mesolimbic dopaminergic activity. In recent years, there has been an assumption that exposure to chronic, rather than acute, stress could result in a state of hyperalgesia in the body due to the inhabitation of mesolimbic dopaminergic mechanisms where both pain and pleasure are controlled36, 37). Hyperalgesia resulting from chronic stress due to not being content with life and work, for example, may lead to the development of chronic disabling LBP.

In the past, the occupational health of the Japanese worker has mainly focused on an ergonomic approach in the management and prevention of LBP. Consistent with Western studies, the present study suggests, however, that we should be more alert to a psychosocial approach to reduce the risk of developing chronic disabling LBP. Although our earlier prospective study indicated that both ergonomic and work-related psychosocial factors were associated with new-onset of disabling LBP in symptom-free Japanese workers38), no ergonomic factors seemingly affect the development of chronic disabling LBP in the present study probably because workers who already experienced disabling LBP at baseline were the focus of the present study. The results are consistent with the guidelines stating that the development of chronic pain and disability results more from work-related psychosocial issues than from physical features34).

There are several limitations to the study. First, generalization of the results of the present study is limited. The majority of the study participants were males. The study cohort was also not a representative sample of all Japanese workers in terms of area as well as range of occupations. Second, the sample size for the present analysis is small. Future research with a larger sample size should be conducted for further identification of potential risk factors of chronic disabling LBP. Third, the context of cognitive and emotional aspects, such as fear-avoidance belief and physician’s attitudes, was not considered in the present study despite being known to affect the development of serious disability. As of the time of data collection, scales measuring fear avoidance were not available in the Japanese language. Since the author developed the Japanese versions of the Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ)39) and the Tampa Scale of Kinesiophobia (TSK)40, 41) after the JOB survey, both are currently available. These scales should also be included in future research. Fourth, misclassification, to some extent, is inevitable. Responses that rely on subjective measurement may be distorted and missing values cannot be avoided due to the nature of a self-assessment survey. Moreover, the possibility for recall bias towards retrospective questions should be kept in mind. Fifth, the present study focuses on the baseline factors affecting the development of chronic disabling LBP under the assumption that workers retained the same status quo as the baseline during the follow-up period. The status in some factors could possibly fluctuate during the period. Such fluctuation in factors was not taken into consideration in the present study. Finally, there may be alternative methods for the selection of potential risk factors prior to conducting multivariate analysis. It should be noted that a more complicated model may offer a better explanation of the data although the results are consistent with Western studies. Further research is needed to identify a full range of potential risk factors for inclusion in future studies.

In conclusion, the present study suggests that psychosocial factors could play a key role in the development of chronic disabling LBP in Japanese workers. Therefore, the occupational health of the Japanese worker should be focused not only on ergonomic interventions but also on psychosocial ones to reduce the impact on the workplace from the repercussions of developing chronic disabling LBP.

References

- 1.van Tulder M, Koes B, Bombardier C. (2002) Low back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 16, 761–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Airaksinen O, Brox JI, Cedraschi C, Hildebrandt J, Klaber-Moffett J, Kovacs F, Mannion AF, Reis S, Staal JB, Ursin H, Zanoli G; COST B13 Working Group on Guidelines for Chronic Low Back Pain (2006) Chapter 4. European guidelines for the management of chronic nonspecific low back pain. Eur Spine J 15, Suppl 2; S192–300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carey TS, Garrett JM, Jackman A, Hadler N. (1999) Recurrence and care seeking after acute back pain: results of a long-term follow-up study. North Carolina Back Pain Project. Med Care 37, 157–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pengel LH, Herbert RD, Maher CG, Refshauge KM. (2003) Acute low back pain: systematic review of its prognosis. BMJ 327, 323–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Von Korff M. (1994) Studying the natural history of back pain. Spine 19 Suppl, 2041S–6S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Von Korff M, Deyo RA, Cherkin D, Barlow W. (1993) Back pain in primary care: outcomes at 1 year. Spine 18, 855–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Croft PR, Macfarlane GJ, Papageorgiou AC, Thomas E, Silman AJ. (1998) Outcome of low back pain in general practice: a prospective study. BMJ 316, 1356–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nachemson AL, Waddell G, Norlund AI. (2000) Epidemiology of neck and low back pain. In: Neck and back pain: The scientific evidence of causes, diagnosis and treatment, Nachemson AL, Jonsson E (Eds.), 165–88, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Vos T, Flaxman AD, Naghavi M, Lozano R, Michaud C, Ezzati M, Shibuya K, Salomon JA, Abdalla S, Aboyans V, Abraham J, Ackerman I, Aggarwal R, Ahn SY, Ali MK, Alvarado M, Anderson HR, Anderson LM, Andrews KG, Atkinson C, Baddour LM, Bahalim AN, Barker-Collo S, Barrero LH, Bartels DH, Basáñez MG, Baxter A, Bell ML, Benjamin EJ, Bennett D, Bernabé E, Bhalla K, Bhandari B, Bikbov B, Bin Abdulhak A, Birbeck G, Black JA, Blencowe H, Blore JD, Blyth F, Bolliger I, Bonaventure A, Boufous S, Bourne R, Boussinesq M, Braithwaite T, Brayne C, Bridgett L, Brooker S, Brooks P, Brugha TS, Bryan-Hancock C, Bucello C, Buchbinder R, Buckle G, Budke CM, Burch M, Burney P, Burstein R, Calabria B, Campbell B, Canter CE, Carabin H, Carapetis J, Carmona L, Cella C, Charlson F, Chen H, Cheng AT, Chou D, Chugh SS, Coffeng LE, Colan SD, Colquhoun S, Colson KE, Condon J, Connor MD, Cooper LT, Corriere M, Cortinovis M, de Vaccaro KC, Couser W, Cowie BC, Criqui MH, Cross M, Dabhadkar KC, Dahiya M, Dahodwala N, Damsere-Derry J, Danaei G, Davis A, De Leo D, Degenhardt L, Dellavalle R, Delossantos A, Denenberg J, Derrett S, Des Jarlais DC, Dharmaratne SD, Dherani M, Diaz-Torne C, Dolk H, Dorsey ER, Driscoll T, Duber H, Ebel B, Edmond K, Elbaz A, Ali SE, Erskine H, Erwin PJ, Espindola P, Ewoigbokhan SE, Farzadfar F, Feigin V, Felson DT, Ferrari A, Ferri CP, Fèvre EM, Finucane MM, Flaxman S, Flood L, Foreman K, Forouzanfar MH, Fowkes FG, Franklin R, Fransen M, Freeman MK, Gabbe BJ, Gabriel SE, Gakidou E, Ganatra HA, Garcia B, Gaspari F, Gillum RF, Gmel G, Gosselin R, Grainger R, Groeger J, Guillemin F, Gunnell D, Gupta R, Haagsma J, Hagan H, Halasa YA, Hall W, Haring D, Haro JM, Harrison JE, Havmoeller R, Hay RJ, Higashi H, Hill C, Hoen B, Hoffman H, Hotez PJ, Hoy D, Huang JJ, Ibeanusi SE, Jacobsen KH, James SL, Jarvis D, Jasrasaria R, Jayaraman S, Johns N, Jonas JB, Karthikeyan G, Kassebaum N, Kawakami N, Keren A, Khoo JP, King CH, Knowlton LM, Kobusingye O, Koranteng A, Krishnamurthi R, Lalloo R, Laslett LL, Lathlean T, Leasher JL, Lee YY, Leigh J, Lim SS, Limb E, Lin JK, Lipnick M, Lipshultz SE, Liu W, Loane M, Ohno SL, Lyons R, Ma J, Mabweijano J, MacIntyre MF, Malekzadeh R, Mallinger L, Manivannan S, Marcenes W, March L, Margolis DJ, Marks GB, Marks R, Matsumori A, Matzopoulos R, Mayosi BM, McAnulty JH, McDermott MM, McGill N, McGrath J, Medina-Mora ME, Meltzer M, Mensah GA, Merriman TR, Meyer AC, Miglioli V, Miller M, Miller TR, Mitchell PB, Mocumbi AO, Moffitt TE, Mokdad AA, Monasta L, Montico M, Moradi-Lakeh M, Moran A, Morawska L, Mori R, Murdoch ME, Mwaniki MK, Naidoo K, Nair MN, Naldi L, Narayan KM, Nelson PK, Nelson RG, Nevitt MC, Newton CR, Nolte S, Norman P, Norman R, O’Donnell M, O’Hanlon S, Olives C, Omer SB, Ortblad K, Osborne R, Ozgediz D, Page A, Pahari B, Pandian JD, Rivero AP, Patten SB, Pearce N, Padilla RP, Perez-Ruiz F, Perico N, Pesudovs K, Phillips D, Phillips MR, Pierce K, Pion S, Polanczyk GV, Polinder S, Pope CA, 3rd, Popova S, Porrini E, Pourmalek F, Prince M, Pullan RL, Ramaiah KD, Ranganathan D, Razavi H, Regan M, Rehm JT, Rein DB, Remuzzi G, Richardson K, Rivara FP, Roberts T, Robinson C, De Leòn FR, Ronfani L, Room R, Rosenfeld LC, Rushton L, Sacco RL, Saha S, Sampson U, Sanchez-Riera L, Sanman E, Schwebel DC, Scott JG, Segui-Gomez M, Shahraz S, Shepard DS, Shin H, Shivakoti R, Singh D, Singh GM, Singh JA, Singleton J, Sleet DA, Sliwa K, Smith E, Smith JL, Stapelberg NJ, Steer A, Steiner T, Stolk WA, Stovner LJ, Sudfeld C, Syed S, Tamburlini G, Tavakkoli M, Taylor HR, Taylor JA, Taylor WJ, Thomas B, Thomson WM, Thurston GD, Tleyjeh IM, Tonelli M, Towbin JA, Truelsen T, Tsilimbaris MK, Ubeda C, Undurraga EA, van der Werf MJ, van Os J, Vavilala MS, Venketasubramanian N, Wang M, Wang W, Watt K, Weatherall DJ, Weinstock MA, Weintraub R, Weisskopf MG, Weissman MM, White RA, Whiteford H, Wiersma ST, Wilkinson JD, Williams HC, Williams SR, Witt E, Wolfe F, Woolf AD, Wulf S, Yeh PH, Zaidi AK, Zheng ZJ, Zonies D, Lopez AD, Murray CJ, AlMazroa MA, Memish ZA. (2012) Years lived with disability (YLDs) for 1160 sequelae of 289 diseases and injuries 1990–2010: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. Lancet 380, 2163–96 (Erratum in: 2013). Lancet 381, 628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Krismer M, van Tulder M; Low Back Pain Group of the Bone and Joint Health Strategies for Europe Project (2007) Strategies for prevention and management of musculoskeletal conditions. Low back pain (non-specific). Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 21, 77–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujii T, Matsudaira K. (2013) Prevalence of low back pain and factors associated with chronic disabling back pain in Japan. Eur Spine J 22, 432–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.The Japan Labour Health and Welfare Organization The 2013. National Livelihood Survey (Kokumin Seikatsu Kiso Chousa) (in Japanese). The Japan Health and Welfare Organization: Tokyo, Japan. http://www.mhlw.go.jp/toukei/saikin/hw/k-tyosa/k-tyosa13/dl/04.pdf Accessed September 16, 2014.

- 13.Pincus T, Burton AK, Vogel S, Field AP. (2002) A systematic review of psychological factors as predictors of chronicity/disability in prospective cohorts of low back pain. Spine 27, E109–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thomas E, Silman AJ, Croft PR, Papageorgiou AC, Jayson MI, Macfarlane GJ. (1999) Predicting who develops chronic low back pain in primary care: a prospective study. BMJ 318, 1662–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turk DC, Rudy TE .(1992) Classification logic and strategies in chronic pain. In: Handbook of Pain Assessment. Turk DC, Melzack R (Eds.), 409–28, NY, Guildford. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams RA, Pruitt SD, Doctor JN, Epping-Jordan JE, Wahlgren DR, Grant I, Patterson TL, Webster JS, Slater MA, Atkinson JH. (1998) The contribution of job satisfaction to the transition from acute to chronic low back pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 79, 366–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McMahon MJ, Gatchel RJ, Polatin PB, Mayer TG. (1997) Early childhood abuse in chronic spinal disorder patients. A major barrier to treatment success. Spine 22, 2408–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakamura M, Nishiwaki Y, Ushida T, Toyama Y. (2014) Prevalence and characteristics of chronic musculoskeletal pain in Japan: a second survey of people with or without chronic pain. J Orthop Sci 19, 339–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Von Korff M, Ormel J, Keefe FJ, Dworkin SF. (1992) Grading the severity of chronic pain. Pain 50, 133–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Muto S, Muto T, Seo A, Yoshida T, Taoda K, Watanabe M. (2006) Prevalence of and risk factors for low back pain among staffs in schools for physically and mentally handicapped children. Ind Health 44, 123–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kawakami N, Kobayashi Y, Takao S, Tsutsumi A. (2005) Effects of web-based supervisor training on supervisor support and psychological distress among workers: a randomized controlled trial. Prev Med 41, 471–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kawakami N, Kobayashi F, Araki S, Haratani T, Furui H. (1995) Assessment of job stress dimensions based on the job demands—control model of employees of telecommunication and electric power companies in Japan: reliability and validity of the Japanese version of the Job Content Questionnaire. Int J Behav Med 2, 358–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haratani T, Kawakami N, Araki S. (1993) Reliability and validity of the Japanese version of NIOSH Generic Job Questionnaire. Sangyo Igaku 35 suppl, S214. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yokoyama K, Araki S, Kawakami N, Tkakeshita T .(1990) Production of the Japanese edition of profile of mood states (POMS): assessment of reliability and validity. Nippon Koshu Eisei Zasshi 37, 913–8 (in Japanese). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shima S, Shikano T, Kitamura T, Asai M. (1985) New self-rating scales for depression. Clin Psychiatry 27, 717–23. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE (1970) Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory. 23–49, Consulting Psychologists Press, Palo Alto. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Isaac M, Tacchini G, Janca A .(1994) Screener for somatoform disorders (SSD). World Health Organization, Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ono Y, Yoshimura K, Yamauchi K, Momose T, Mizushima H, Asai M. (1996) Psychological well-being and ill-being: WHO Subjective Well-being Inventory (SUBI). Jpn J Stress Sci 10, 273–8. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shimomitsu T, Odagiri Y. (2004) The brief job stress questionnaire. Occup Ment Health 12, 25–36. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Matsudaira K, Palmer KT, Reading I, Hirai M, Yoshimura N, Coggon D. (2011) Prevalence and correlates of regional pain and associated disability in Japanese workers. Occup Environ Med 68, 191–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brinkman GL, Coates EO., Jr (1963) The effect of bronchitis, smoking, and occupation on ventilation. Am Rev Respir Dis 87, 684–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Akaha H, Matsudaira K, Takeshita K, Oka H, Hara N, Nakamura K. (2008) Modified measurement of finger-floor distance—Self assessment bending scale—. J Lumbar Spine Disord 14, 164–9. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Williams RA, Pruitt SD, Doctor JN, Epping-Jordan JE, Wahlgren DR, Grant I, Patterson TL, Webster JS, Slater MA, Atkinson JH. (1998) The contribution of job satisfaction to the transition from acute to chronic low back pain. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 79, 366–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Waddell G, Burton AK. (2001) Occupational health guidelines for the management of low back pain at work: evidence review. Occup Med (Lond) 51, 124–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Heymans MW, Anema JR, van Buuren S, Knol DL, van Mechelen W, de Vet HC. (2009) Return to work in a cohort of low back pain patients: development and validation of a clinical prediction rule. J Occup Rehabil 19, 155–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wood PB. (2006) Mesolimbic dopaminergic mechanisms and pain control. Pain 120, 230–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Leknes S, Tracey I. (2008) A common neurobiology for pain and pleasure. Nat Rev Neurosci 9, 314–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Matsudaira K, Konishi H, Miyoshi K, Isomura T, Takeshita K, Hara N, Yamada K, Machida H. (2012) Potential risk factors for new onset of back pain disability in Japanese workers: findings from the Japan epidemiological research of occupation-related back pain study. Spine 37, 1324–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Waddell G, Newton M, Henderson I, Somerville D, Main CJ. (1993) A Fear-Avoidance Beliefs Questionnaire (FABQ) and the role of fear-avoidance beliefs in chronic low back pain and disability. Pain 52, 157–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Miller RP, Kori SH, Todd DD. (1991) The Tampa Scale: a measure of kinisophobia. Clin J Pain 7, 51–2. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kori KS, Miller RP, Todd DD. (1990) Kinesiophobia: a new view of chronic pain behavior. Pain Manag 3, 35–43. [Google Scholar]