Abstract

This study addressed the hypothesis that inhibiting the soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH)-mediated degradation of epoxy-fatty acids, notably epoxyeicosatrienoic acids, has an additional impact against cardiovascular damage in insulin resistance, beyond its previously demonstrated beneficial effect on glucose homeostasis. The cardiovascular and metabolic effects of the sEH inhibitor trans-4-[4-(3-adamantan-1-yl-ureido)-cyclohexyloxy]-benzoic acid (t-AUCB; 10 mg/l in drinking water) were compared with those of the sulfonylurea glibenclamide (80 mg/l), both administered for 8 wk in FVB mice subjected to a high-fat diet (HFD; 60% fat) for 16 wk. Mice on control chow diet (10% fat) and nontreated HFD mice served as controls. Glibenclamide and t-AUCB similarly prevented the increased fasting glycemia in HFD mice, but only t-AUCB improved glucose tolerance and decreased gluconeogenesis, without modifying weight gain. Moreover, t-AUCB reduced adipose tissue inflammation, plasma free fatty acids, and LDL cholesterol and prevented hepatic steatosis. Furthermore, only the sEH inhibitor improved endothelium-dependent relaxations to acetylcholine, assessed by myography in isolated coronary arteries. This improvement was related to a restoration of epoxyeicosatrienoic acid and nitric oxide pathways, as shown by the increased inhibitory effects of the nitric oxide synthase and cytochrome P-450 epoxygenase inhibitors l-NA and MSPPOH on these relaxations. Moreover, t-AUCB decreased cardiac hypertrophy, fibrosis, and inflammation and improved diastolic function, as demonstrated by the increased E/A ratio (echocardiography) and decreased slope of the end-diastolic pressure-volume relation (invasive hemodynamics). These results demonstrate that sEH inhibition improves coronary endothelial function and prevents cardiac remodeling and diastolic dysfunction in obese insulin-resistant mice.

Keywords: insulin resistance, soluble epoxide hydrolase, endothelium, cardiac function

endothelial dysfunction and accelerated atherosclerosis, secondary to the chronic pro-inflammatory state generated by hyperinsulinemia, hyperglycemia, and dyslipidemia, play a critical role in the development of cardiovascular complications of type 2 diabetes (12, 17, 22). Strategies for multiple risk-factor control including glucose, lipid, and blood pressure levels have shown a clear benefit on cardiovascular outcome in type 2 diabetic patients (22, 23). However, these patients are still at increased cardiovascular risk, and new therapeutic targets are needed (22, 23).

In this context, pharmacological therapies targeting both the metabolic and cardiovascular abnormalities in type 2 diabetes would be ideal candidates. An emerging pharmacological approach consists in inhibiting soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH), which is an ubiquitously distributed enzyme that rapidly metabolizes epoxy-fatty acids, in particular epoxyeicosatrienoic acids (EETs), into their corresponding less active diols (3, 20). EETs synthesized in endothelial cells by cytochrome P-450 (CYP450) epoxygenases contribute to the regulation of vascular tone by acting as endothelium-derived hyperpolarizing factors (EDHF) through the activation of calcium-activated potassium (KCa) channels, and display potent effects against inflammation and remodeling (3, 20). In addition, CYP450 epoxygenases and sEH are expressed in metabolic organs and locally synthesized EETs appear to contribute to the regulation of glucose and lipid homeostasis (3, 20).

Recent evidence indicates that CYP450 epoxygenase overexpression or sEH inhibition/genetic deletion improves glucose homeostasis in diabetes by increasing both insulin release and sensitivity (14, 15, 24). However, the associated impact on endothelial dysfunction and cardiac alterations remains to be thoroughly investigated in particular in a context of type 2 diabetes. Indeed, in insulin-resistant animals, endothelial dysfunction is associated with modifications in the vascular expression of CYP450, sEH, and KCa channels, thus giving indirect evidence for the presence of an altered EET pathway at the cardiovascular level (19, 26). Finally, whether sEH inhibition prevents adipose tissue inflammation, which triggers the development of insulin resistance, and/or improves lipid homeostasis remains largely unknown (7).

Thus, the aim of the present study was to compare, in a murine model of insulin resistance, the effects of the chronic administration of a sEH inhibitor to those of a pure prevention of hyperglycemia by a sulfonylurea on cardiovascular damage, with particular emphasis on endothelial function, cardiac function, and structure, as well as on metabolic abnormalities.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The protocol was approved by a local institutional review committee and conducted in accordance with the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals.

Animal model and treatments.

Male FVB/N mice (Janvier), 6–8 wk of age, weighing 26–30 g were used for these experiments. This strain was chosen based on our previous studies showing that, in accordance with our findings in humans, EETs contribute with nitric oxide (NO) to endothelium-dependent responses in arteries isolated from these mice (2, 8). Mice were fed with either a standard chow diet (control mice, n = 48, D12450B, 10% energy by fat; Research Diets) or a high-fat diet (HFD; n = 160, D12492B, 60% energy by fat; Research Diets) for 16 wk. Eight weeks after starting the HFD, mice were randomized to receive either the potent sEH inhibitor trans-4-(4-(3-adamantan-1-yl-ureido)-cyclohexyloxy)-benzoic acid (t-AUCB; 10 mg/l in drinking water, n = 56) or glibenclamide (80 mg/l, n = 50; Sigma-Aldrich) or were not treated (n = 54) for the remaining 8 wk (10). Animal body weight along with food and caloric intake were monitored weekly. Blood pressure and heart rate were monitored every 4 wk in trained conscious animals using a noninvasive computerized tail-cuff system (CODA 2; Kent Scientific) (8). The blood level of t-AUCB was quantified by LC-MS/MS (10).

Metabolic parameters.

Fasting glucose and insulin levels were determined before [week (W)0], 8 wk (W8), and 16 wk (W16) after starting normal chow diet or HFD. Briefly, after a 16-h fast, glycemia was measured in blood collected from the tail using a glucometer (StatStrip Xpress; Nova Biomedical), and insulin was determined in plasma, obtained from retro-orbital blood collection in mice anesthetized with isoflurane (1% to 2%), by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (Ultra Sensitive Insulin mouse Assay; Crystal Chem). Glucose, pyruvate, and insulin tolerance tests (GTT, PTT, and ITT, respectively) were performed at W16 to assess glucose tolerance, gluconeogenesis, and peripheral insulin sensitivity, respectively. For glucose and pyruvate tolerance tests, mice were fasted for 16 h and glucose or pyruvate were administered by gavage at the dose of 2 mg/g body wt. For insulin tolerance test, mice were fasted for 6 h and human insulin (1 mU/g ip, Actrapid; Novo Nordisk A/S) was administered. For all tests, blood glucose values were measured just before and 15, 30, 45, 60, 90, and 120 min after administration, and the area under the curve was calculated for each animal.

Plasma LDL cholesterol, triglycerides, and free fatty acids were measured at W16 by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (EHDL-100, EFFA-100, and ETGA-200; BioAssay Systems). For determination of hepatic steatosis, freshly dissected livers were frozen and cryostat sections 8-μm thick were further processed for Oil Red O lipid staining.

The mRNA expression of TNF-α, monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1), IL-1β, IL-6, IL-10, endothelial NO synthase (eNOS), and the macrophage marker CD68 was assessed by real-time RT-PCR in epididymal white adipose tissue. Values were normalized using TATA box binding protein mRNA and expressed as the percentage of gene variation in comparison with that of control mice.

Coronary vascular studies.

Coronary vascular reactivity was evaluated at W8 and W16 by myography (Dual Wire Myograph System; Danish Myo Technology). For this purpose, mice were anesthetized (3.6 mg/kg xylazine, 90 mg/kg ketamine), and the heart was immediately removed and placed in cold, oxygenated Krebs buffer. A segment of the septal coronary artery, 1 mm long and ∼100 μm in diameter, was carefully dissected and mounted in a small vessel myograph for isometric tension recording. All measurements were performed after vessel contraction with 10−5 M serotonin, and pharmacological inhibitors were applied for 30 min before assessing the relaxant responses. The endothelium-dependent relaxations to acetylcholine (10−9 to 10−4.5 M) were assessed in the absence and in the presence of the NOS inhibitor Nω-nitro-l-arginine (l-NA; 10−4 M), the CYP450 epoxygenase inhibitor N-methylsulfonyl-6-(2-propargyloxyphenyl)-hexanamide (MSPPOH; 10−4 M), and apamin + TRAM34 (10−5 M each), the inhibitors of small- and intermediate-conductance calcium-activated potassium (SKCa and IKCa) channels, which mediate the classical EDH response without necessary involvement of a chemical factor, were assessed (3, 8). Endothelium-independent relaxations to the NO donor sodium nitroprusside (10−9 to 10−4.5 M) and the coronary relaxing responses to NS1619, an opener of large-conductance calcium-activated potassium (BKCa) channels (10−6 to 10−4.5 M), which are the main smooth muscle cellular targets of EETs mediating their hyperpolarizing effect, and to NS309, an opener of SKCa and IKCa channels (10−8 to 10−5 M), were assessed (3, 8). Coronary protein expressions of eNOS, sEH, and BKCa channels were determined by Western blot analysis, and results were normalized to actin level (8, 18).

Cardiac evaluations.

In mice anesthetized with isoflurane (1% to 2%), left ventricular (LV) dimensions, and function were assessed at W0, W8, and W16, using a Vivid 7 ultrasound device (GE medical) (8, 18). The heart was imaged in the two-dimensional mode in the parasternal short-axis view. With the use of M mode image, LV end-diastolic (EDD) and systolic diameters (ESD), and end-diastolic LV wall thickness were measured. Ejection fraction (EF) was calculated from the LV cross-sectional area as EF (%) = ((LVDA − LVSA)/LVDA) × 100 where LVDA and LVSA are LV diastolic and systolic area, estimated from EDD and ESD. In addition, a pulsed Doppler of the LV outflow was performed to obtain heart rate (HR) and velocity time integral (VTI) allowing the calculation of stroke volume (SV = π × LV outflow radius2 × VTI) and cardiac output (CO = SV × HR). Furthermore, Doppler measurements were made at the tip of the mitral leaflets for diastolic filling profiles in the apical four-chamber view, allowing to determine peak early (E) and late (A) mitral inflow velocities, and calculation of the E/A ratio.

Myocardial perfusion was assessed at W16 by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) in anesthetized mice using a 4.7 T horizontal bore scanner (Bruker) and the arterial spin labeling technique (18).

LV hemodynamics were assessed at W16 in anesthetized mice (8, 18). A 2F miniaturized combined conductance catheter-micromanometer (model SPR-838; Millar) connected to a pressure-conductance unit (MPCU-200; Millar) was introduced in the carotid artery and advanced into the left ventricle. LV pressure-volume loops were recorded at baseline and during loading by gently occluding the abdominal aorta with a cotton swab, allowing the calculation of LV end-systolic and end-diastolic pressures, LV dP/dtmin/dP/dtmax, LV relaxation constant τ (Weiss method), and LV end-systolic and end-diastolic pressure-volume relations as indicators of load-independent LV passive elastance and compliance function respectively.

Finally, the heart was harvested, the ventricles were weighed and a section of the left ventricle was snap frozen for subsequent determination of LV collagen density, using 8-micrometer-thick histological slices stained with Sirius Red. Leukocyte infiltration was assessed by the quantification of CD45-positive cells by immunohistochemistry. In addition, the number of F4/80-, CD3-, and GR-1-positive cells, as markers of macrophages, lymphocytes T, and neutrophils, respectively, was determined. The LV mRNA expression of the CYP450 epoxygenases CYP2J5 and CYP2C29 was assessed by real-time RT-PCR and normalized using GAPDH and β2-microglobulin mRNA expressions. The LV protein expressions of phospho-Akt (pAkt, Ser473), Akt, NF-κB, phosphoIκBα (pIκB, Ser32/36), IκBα, eNOS, sEH, NOX4, catalase, superoxide dismutase (SOD), and actin were determined by Western blot analysis (8, 18).

Statistical analysis.

All values are expressed as means ± SE. The Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess normality. To evaluate the effect of HFD, all parameters obtained in control and nontreated HFD mice were compared by unpaired t-test or nonparametric Wilcoxon rank-sum test as appropriate. To evaluate the effect of the pharmacological treatments, nontreated HFD mice and HFD mice treated with either glibenclamide or t-AUCB were compared using one-way ANOVA or nonparametric Kruskall-Wallis test as appropriate, followed, in case of significance, by Tukey-Kramer test or Dunn's test for multiple comparisons. The evolution of glycemia, insulinemia, blood pressure, heart rate, and echocardiographic parameters between W0, W8, and W16 were analyzed in each group using paired t-test. Coronary experiments, GTT, ITT, and PTT were analyzed by repeated-measured ANOVA for serial measurements. Statistical analysis was performed with NCSS software (version 07.1.14). A two-sided P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

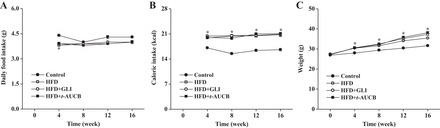

At W16, the blood concentration of t-AUCB in HFD mice treated for 8 wk was 16.2 ± 7.1 nmol/l (n = 11). Food intake was similar between groups, but caloric intake was higher in nontreated HFD mice compared with control mice, resulting in a higher body weight gain (Fig. 1). These parameters were not affected by glibenclamide nor by t-AUCB.

Fig. 1.

Average food intake (A), caloric intake (B), and weight gain (C) in control mice (n = 30), nontreated high-fat diet (HFD) mice (n = 28), and HFD mice treated with glibenclamide (GLI; n = 30) or with t-AUCB (n = 36) from week (W)0 to W16. *P < 0.05 vs. control.

Effects of sEH inhibition on metabolic parameters.

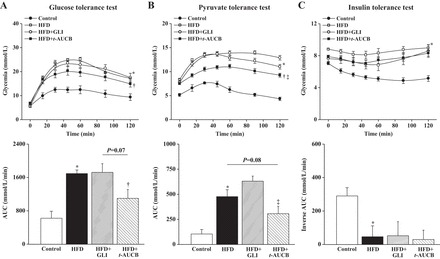

When compared with that of control mice, there was an increase in fasting glucose and insulin levels at W8 and W16 in nontreated HFD mice (Table 1). In addition, GTT, PTT, and ITT were impaired at W16 in HFD mice (Fig. 2), further demonstrating the development of insulin resistance.

Table 1.

Evolution of peripheral blood pressure, heart rate, fasting glycemia, and insulinemia from W0 to W16 in control mice, nontreated high-fat-diet mice, and high-fat-diet mice treated with glibenclamide or with t-AUCB

| Control |

Nontreated High-Fat Diet |

High-Fat Diet + Glibenclamide |

High-Fat Diet + t-AUCB |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parameters | W0 | W8 | W16 | W0 | W8 | W16 | W0 | W8 | W16 | W0 | W8 | W16 |

| Blood pressure, mmHg | ||||||||||||

| Systolic | 106 ± 5 | 105 ± 6 | 101 ± 5 | 107 ± 1 | 103 ± 7 | 99 ± 7 | 105 ± 5 | 97 ± 8 | 102 ± 11 | 107 ± 5 | 101 ± 7 | 95 ± 5 |

| Diastolic | 76 ± 3 | 70 ± 6 | 75 ± 3 | 72 ± 2 | 67 ± 6 | 72 ± 5 | 70 ± 1 | 66 ± 8 | 66 ± 6 | 77 ± 5 | 72 ± 6 | 72 ± 4 |

| Heart rate, beats/min | 694 ± 64 | 673 ± 22 | 748 ± 19 | 703 ± 31 | 696 ± 43 | 699 ± 63 | 751 ± 29 | 757 ± 28 | 732 ± 86 | 707 ± 91 | 750 ± 42 | 698 ± 50 |

| Glycemia, mmol/l | 6.0 ± 0.6 | 5.6 ± 0.6 | 5.4 ± 0.2 | 6.0 ± 0.7 | 7.6 ± 0.5*† | 8.0 ± 0.8*† | 5.7 ± 0.6 | 7.6 ± 0.3* | 5.1 ± 0.3‡§ | 5.9 ± 0.5 | 8.3 ± 0.4* | 5.6 ± 0.2‡§ |

| Insulinemia, mU/l | 10.2 ± 0.1 | 10.8 ± 1.5 | 9.7 ± 1.1 | 8.9 ± 0.3 | 13.1 ± 1.1*† | 15.4 ± 0.9*† | 10.7 ± 2.1 | 16.0 ± 2.7* | 18.2 ± 2.3* | 10.0 ± 1.8 | 16.5 ± 2.3* | 12.5 ± 2.4 |

Values are means ± SE. t-AUCB, trans-4-[4-(3-adamantan-1-yl-ureido)-cyclohexyloxy]-benzoic acid.

P < 0.05 vs. week (W)0;

P < 0.05 vs. control mice;

P < 0.05 vs. W8;

P < 0.05 vs. nontreated high-fat diet (n = 4–11 per group).

Fig. 2.

Evolution of glycemia during glucose (A), pyruvate (B), and insulin (C) tolerance tests expressed as absolute values or as area under the curve (AUC) at W16 in control mice (n = 4–8), nontreated HFD mice (n = 4–10), and HFD mice treated with GLI (n = 5–12) or with t-AUCB (n = 5–11). *P < 0.05 vs. control; †P < 0.05 vs. nontreated HFD; ‡P < 0.05 vs. HFD + GLI.

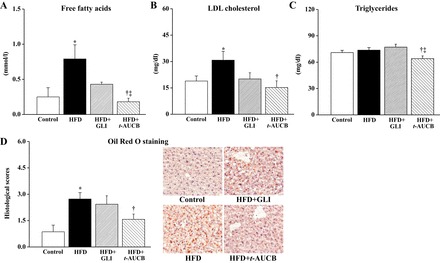

Regarding plasma lipids, nontreated HFD mice had increased free fatty acids (Fig. 3A) and LDL cholesterol (Fig. 3B) compared with those of control mice, without change in triglyceride levels (Fig. 3C). Moreover, there was an increased hepatic lipid content in HFD mice (Fig. 3D). In adipose tissue, the mRNA expression of eNOS was decreased while the expressions of MCP-1, TNF-α, and CD68 were increased, without change in IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-10 (Table 2).

Fig. 3.

Plasma levels of free fatty acids (A), LDL cholesterol (B), triglycerides (C), and histological scores of lipid content in the liver (D) at W16 in control mice (n = 4–9), nontreated HFD mice (n = 4–8), and HFD mice treated with GLI (n = 5–11) or with t-AUCB (n = 5–10). *P < 0.05 vs. control; †P < 0.05 vs. nontreated HFD; ‡P < 0.05 vs. HFD + GLI.

Table 2.

Adipose tissue mRNA expressions

| Parameters, % | Control | Nontreated High-Fat Diet | High-Fat Diet + Glibenclamide | High-Fat Diet + t-AUCB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TNF-α | 100 ± 26 | 150 ± 6* | 134 ± 29 | 83 ± 11† |

| Monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 | 100 ± 35 | 751 ± 231* | 650 ± 95 | 257 ± 41†‡ |

| IL-1β | 100 ± 23 | 206 ± 79 | 146 ± 28 | 132 ± 23 |

| IL-6 | 100 ± 67 | 197 ± 72 | 101 ± 31 | 43 ± 5 |

| IL-10 | 100 ± 42 | 132 ± 36 | 64 ± 6 | 102 ± 15 |

| Endothelial nitric oxide synthase | 100 ± 6 | 68 ± 7* | 51 ± 11 | 107 ± 6†‡ |

| CD68 | 100 ± 24 | 362 ± 62* | 592 ± 219 | 207 ± 8†‡ |

Values are means ± SE.

P < 0.05 vs. control;

P < 0.05 vs. nontreated high-fat diet;

P < 0.05 vs. glibenclamide (n = 4–11 per group).

The increase in fasting glycemia at W16 was similarly prevented by glibenclamide and t-AUCB. The increase in fasting insulinemia was not affected by glibenclamide but was partially prevented by t-AUCB (Table 1). Only t-AUCB improved GTT and PTT, without affecting ITT (Fig. 2).

Only t-AUCB significantly prevented the increase in plasma free fatty acids and LDL cholesterol and reduced triglyceride levels (Fig. 3, A–C). At last, t-AUCB but not glibenclamide prevented hepatic steatosis (Fig. 3D), as well as the decreased expression of eNOS and the increased expressions of MCP-1, TNF-α, and CD68 in adipose tissue (Table 2).

Effects of sEH inhibition on coronary vascular reactivity.

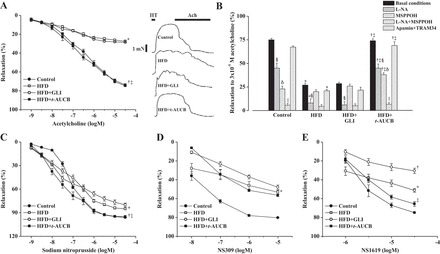

When compared with those of control mice, the coronary endothelium-dependent relaxations to acetylcholine were markedly reduced in nontreated HFD mice at W16 (Fig. 4A). l-NA decreased these relaxations in both groups, but this decrease was lesser in HFD mice than in control mice (Fig. 4B; −21 ± 4% vs. −33 ± 5% at 3 × 10−5 M acetylcholine, P < 0.01), showing an altered NO pathway. MSPPOH alone or in combination with l-NA decreased these relaxations in control but not in HFD mice (Fig. 4B), demonstrating the abolition of EET pathway. In contrast, apamin + TRAM34 did not modify the coronary relaxations to acetylcholine in control nor in nontreated HFD mice (Fig. 4B).

Fig. 4.

Coronary endothelium-dependent relaxations to acetylcholine (ACh) after vessel contraction with 10−5 M serotonin (HT) under basal conditions (A: mean values and representative recordings), inhibitory effect of Nω-nitro-l-arginine (l-NA), N-methylsulfonyl-6-(2-propargyloxyphenyl)-hexanamide (MSPPOH), l-NA + MSPPOH, and apamin + TRAM34 on the relaxations to 3 × 10−5 M acetylcholine (B), endothelium-independent relaxations to sodium nitroprusside (C), and relaxations to NS309 (D) and NS1619 (E), at W16 in control mice, nontreated HFD mice, HFD mice treated with GLI or with t-AUCB (n = 4 to 5 per condition). *P < 0.05, nontreated HFD vs. control; †P < 0.05, HFD + t-AUCB vs. nontreated HFD; ‡P < 0.05, HFD + t-AUCB vs. HFD + GLI; §P < 0.05, l-NA vs. control conditions; δP < 0.05, MSPPOH vs. control conditions; ||P < 0.05, l-NA + MSPPOH vs. l-NA.

The relaxations to acetylcholine were restored by t-AUCB but not by glibenclamide. This beneficial effect of t-AUCB is related to an improvement in NO pathway as shown by the increased inhibitory effects of l-NA (−28 ± 4% at 3 × 10−5 M acetylcholine, P < 0.05 vs. nontreated HFD mice) on acetylcholine-induced relaxations. In addition, MSPPOH alone or in combination with l-NA decreased these relaxations in HFD mice treated with t-AUCB, whereas it was without effect in nontreated HFD mice, demonstrating the improvement in EET pathway. Moreover, the inhibitory effect of MSPPOH was already decreased in nontreated HFD mice at W8 compared with control mice (−24 ± 6% vs. −53 ± 2% at 3 × 10−5 M acetylcholine, P < 0.01), showing that t-AUCB not only prevents but reverses endothelial dysfunction by restoring EET pathway. Apamin + TRAM34 did not affect the relaxations to acetylcholine in HFD mice treated with t-AUCB or glibenclamide.

Furthermore, the coronary endothelium-independent relaxations to sodium nitroprusside (Fig. 4C) were also impaired in HFD mice, and t-AUCB but not glibenclamide prevented this impairment. Finally, the relaxations to NS309 (Fig. 4D) and NS1619 (Fig. 4E) were also decreased in HFD mice, and this was not improved by t-AUCB. In contrast, glibenclamide further decreased the relaxations to NS1619, an effect that may be related to hyperinsulinemia.

Western blot analysis showed no significant difference between groups for the coronary expressions of sEH and BKCa channels but eNOS expression tended to be increased by t-AUCB (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Western-blot analysis of left descending coronary artery protein expressions of endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS), soluble epoxide hydrolase (sEH), and large-conductance calcium-activated potassium (BKCa) channels, normalized to smooth muscle actin at W16 in control mice (n = 6–8), nontreated HFD mice (n = 5 to 6), and HFD mice treated with GLI (n = 5 to 6) or with t-AUCB (n = 6).

Effects of sEH inhibition on hemodynamics, cardiac function, and structure.

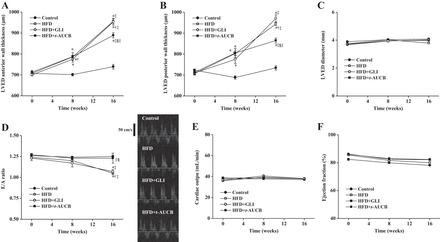

Peripheral blood pressure and heart rate remained similar between groups from W0 to W16 (Table 1). Echocardiography showed a progressive increase in LV end-diastolic anterior and posterior wall thicknesses from W0 to W16 in nontreated HFD mice compared with control mice, without change in LV end-diastolic diameter (Fig. 6, A–C). The presence of LV hypertrophy was confirmed at W16 by the higher LV weight-to-tibia length ratio in HFD mice (Fig. 7A). This was associated with an increased LV collagen density (Fig. 7B) and a nonsignificant enhancement of CD45- and F4/80-positive cells (Fig. 7C), without change in the number of CD3- and GR-1-positive cells (data not shown). Western blot analysis showed no change in the LV protein expressions of pAkt, pIκBα, eNOS, sEH, catalase, and SOD but an increased expression of NF-κB and NOX4 (Fig. 7D). LV mRNA expression of CYP2J2 and CYP2C29 were similar in nontreated HFD mice compared with control mice (Fig. 7E).

Fig. 6.

Assessment of left ventricular end-diastolic (LVED) anterior wall thickness (A), LVED posterior wall thickness (B), LVED diameter (C), E/A ratio (D: mean values and representative recordings), cardiac output (E), and ejection fraction (F) in control mice (n = 6–9), nontreated HFD mice (n = 9–11), and HFD mice treated with GLI (n = 6–9) or with t-AUCB (n = 8–10) at W0, W8, and W16. *P < 0.05 vs. W0; †P < 0.05 vs. control; ‡P < 0.05 vs. W8; §P < 0.05 vs. nontreated HFD; ||P < 0.05 vs. HFD + GLI.

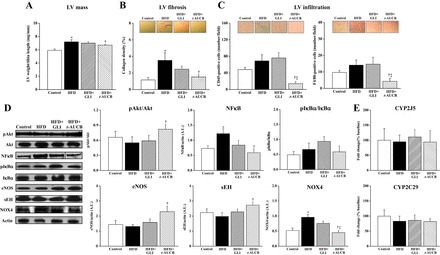

Fig. 7.

Left ventricular (LV) weight-to-tibia length ratio (A), LV collagen density (B), LV infiltration (C), LV protein expression of phospho-Akt (pAkt) normalized to Akt, NF-κB (dotted line indicates gel splicing), pIκB normalized to IκB, sEH, NOX4, catalase, and SOD normalized to actin (D), and LV mRNA expression of CYP2J5 and CYP2C9 normalized to GAPDH and β2-microglobulin, at W16 in control mice (n = 6–16), nontreated HFD mice (n = 6–15), and HFD mice treated with GLI (n = 6–15) or with t-AUCB (n = 6–18). *P < 0.05 vs. control; †P < 0.05 vs. nontreated HFD; ‡P < 0.05 vs. HFD + GLI.

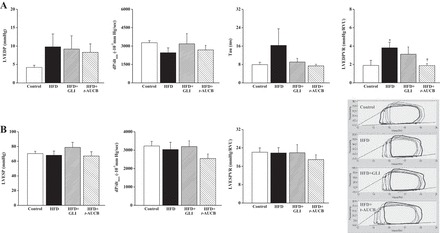

Furthermore, there was a decrease in the E/A ratio from W0 to W16 in nontreated HFD mice compared with control mice, suggesting diastolic dysfunction (Fig. 6D). Diastolic dysfunction was confirmed by invasive hemodynamics, demonstrating increased slope of the LV end-diastolic pressure-volume relationship, indicator of load-independent LV passive compliance, in HFD mice, whereas LV end-diastolic pressure, dP/dtmin, and relaxation constant τ were not significantly modified (Fig. 8A). In contrast, systolic function remained similar between groups, as shown by the absence of difference for cardiac output and ejection fraction (Fig. 6, E and F), as well as for end-systolic pressure, dP/dtmax, and slope of the end-systolic pressure-volume relationship (Fig. 8B). Finally, myocardial perfusion was reduced in nontreated HFD mice (10.6 ± 0.7 ml·min−1·g−1, n = 9) compared with control mice (12.5 ± 1.0 ml·min−1·g−1, n = 10, P < 0.001).

Fig. 8.

Markers of diastolic function (A): left ventricular end-diastolic pressure (LVEDP), LV minimal change in pressure over time (dP/dtmin), LV relaxation constant τ, LV end-diastolic pressure-volume relation (LVEDPVR); and markers of systolic function (B): LV end-systolic pressure (LVESP), LV maximal change in pressure over time (dP/dtmax), LV end-systolic pressure-volume relation (LVESPVR) obtained by invasive hemodynamics (mean values and representative recordings) at W16 in control mice (n = 6), nontreated HFD mice (n = 7), and HFD mice treated with GLI (n = 4) or with t-AUCB (n = 8). *P < 0.05 vs. control; †P < 0.05 vs. nontreated HFD.

LV remodeling was not affected by glibenclamide but was improved by t-AUCB, as shown at W16 by their decreased LV anterior and posterior wall thicknesses, without change in LV end-diastolic diameter (Fig. 6, A–C). Similarly, t-AUCB but not glibenclamide significantly reduced LV weight, collagen density, CD45- and F4/80-positive cells, NF-κB, and NOX4 expressions and increased LV pAkt and sEH expression (Fig. 7D). No change in the number of CD3- and GR-1-positive cells (data not shown), in the protein expressions of pIκBα, catalase, and SOD, as well as in CYP2J5 and CYP2C29 mRNA expressions (Fig. 7, D and E), was observed.

Furthermore, only t-AUCB improved cardiac diastolic dysfunction, as shown by the increased E/A ratio (Fig. 6D) and the decreased LV end-diastolic pressure-volume relationship, compared with nontreated HFD mice (Fig. 8A). Cardiac systolic function was not altered either by glibenclamide or t-AUCB (Figs. 6, E and F, and 8B). Finally, myocardial perfusion was not affected by glibenclamide (11.2 ± 1.2 ml·min−1·g−1, n = 11) nor by t-AUCB (10.6 ± 1.1 ml·min−1·g−1, n = 11) compared with nontreated HFD mice.

DISCUSSION

The major finding of this study is that the chronic administration of a sEH inhibitor not only prevents hyperglycemia but also improves cardiovascular function and structure in a model of insulin resistance.

High-fat feeding in FVB mice was associated with the development of insulin resistance, illustrated by the progressive increase in fasting insulinemia and glycemia, and confirmed by glucose intolerance and insulin resistance. Moreover, the altered PTT showed an enhanced gluconeogenesis, which is a main mechanism of the increased fasting glycemia (21). Furthermore, adipose tissue activation was demonstrated in HFD mice by the decreased eNOS expression and the increased expressions of TNF-α, MCP-1, and CD68, and in circulating levels of free fatty acids. The associated hepatic steatosis may contribute to alter lipid metabolism, illustrated by the increase in plasma LDL cholesterol.

With regard to the cardiovascular function and structure, we first observed the presence of a prominent endothelial dysfunction in coronary arteries of HFD mice, as previously observed in other vascular beds in animal models of insulin resistance (11, 25, 26). However, we demonstrated for the first time that a progressive alteration in EET pathway is a major contributor, as shown by the decrease at W8 and the complete loss at W16 of the inhibitory effect of MSPPOH on the coronary relaxations to acetylcholine in HFD mice. Because coronary sEH expression was not increased, an increased activity of sEH may exist, as previously observed in adipocytes of HFD mice (5). Additionally, a decreased activity of BKCa channels, which is the main cellular targets of EETs mediating their hyperpolarizing effects, probably contributes. Indeed, there was an altered coronary relaxation to the opener of these channels NS1619, without change in protein expression in HFD mice. Moreover, the reduced relaxing responses to NS309 suggest that, in addition to EETs, the classical EDH response mediated by endothelial SKCa and IKCa channels is altered in HFD mice. However, this hypothesis cannot be confirmed in the present work because the endothelium-dependent relaxations to acetylcholine were not mediated by these channels, as shown by the absence of effect of apamin + TRAM34. In addition, our results also show an alteration in NO pathway, illustrated by the decreased responsiveness to l-NA in HFD mice associated to the decrease in smooth muscle sensitivity to the NO donor sodium nitroprusside. Furthermore, LV concentric hypertrophy and fibrosis, associated to diastolic dysfunction, were demonstrated in HFD mice. These alterations are classically reported in insulin resistance and early stage of type 2 diabetes, even in absence of blood pressure elevation (4). Many factors may contribute to diabetic cardiomyopathy, including cardiac insulin resistance, altered calcium homeostasis, lipid accumulation, adipokines such as leptin, and an associated pro-inflammatory and pro-oxidative cardiac phenotype, as demonstrated in the present work (4). Moreover, myocardial perfusion was reduced in HFD mice, maybe contributing to alter cardiac function and structure (1).

We tested the potent sEH inhibitor t-AUCB administered in drinking water at the dose of 10 mg/l, allowing to reach a blood concentration higher than the IC50 determined in vitro, using the recombinant murine sEH enzyme (8 nM) (10). In accordance with the effective inhibition of sEH, we observed an increased expression of this enzyme at least in the cardiac tissue in mice treated with t-AUCB. This effect, which was previously observed with another sEH inhibitor, may represent a compensatory drawback mechanism (8). First of all, caloric intake and weight gain were not reduced by glibenclamide or by t-AUCB and, thus, such an effect cannot have contributed to the impact of sEH inhibition on glucose and lipid homeostasis. In fact, this result is consistent with previous studies (11, 13) except one (6). In the latter, the sEH inhibition promoted weigh loss by reducing the appetite and energy expenditure of mice receiving a high-fat and high-fructose diet (6). In this context, sEH inhibition reversed the increase in fasting glycemia in HFD mice and, importantly, this hypoglycemic effect was of similar magnitude to that obtained with the insulin secretagogue glibenclamide, without modification in weight gain. Prevention of hyperglycemia has been previously obtained in animal models of insulin resistance using sEH inhibition/gene deletion or CYP450 epoxygenase overexpression (15, 24, 25). Regarding the mechanisms of the hypoglycemic effect of sEH inhibitors, it can be assumed that the impact of such strategy on insulin resistance is inconstant, varying with the models and methods used and the period of investigations chosen after disease onset. Thus an improvement in insulin resistance with sEH inhibitors has been observed in the pioneering work of Luria and collaborators (14) but not in all studies thereafter (6, 13). In this work, t-AUCB partially prevented the increase in fasting insulinemia, glucose intolerance, and altered gluconeogenesis, but without affecting ITT. These results suggest an improvement in insulin sensitivity mainly at the hepatic but less at the muscular level. In addition, both drugs appeared to improve lipid homeostasis, but only the effects of t-AUCB were significant. This difference may be notably related to the prevention of adipose tissue activation, which triggers systemic inflammation and insulin resistance in obesity (7). In fact, t-AUCB alleviated in fat tissues the increased mRNA expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and CD68 and the decreased eNOS expression, as well as it normalized free fatty acids and triglycerides. In addition, the decrease in hepatic steatosis probably contributed to improve hepatic function, as shown by the normalization of plasma LDL cholesterol (11, 13).

Furthermore, sEH inhibition reversed the endothelial dysfunction of coronary arteries in HFD mice, while glibenclamide did not, beside a similar hypoglycemic effect. Previous studies reported a protective effect of sEH inhibitors on the endothelial function of diabetic mesenteric arteries and aortas, but the mechanisms involved were not identified (11, 25). In this study, we show an improvement in EET availability, as expected from the prevention of EET degradation by t-AUCB, but without complete restoration of BKCa channels activity. Moreover, sEH inhibition improved the NO-mediated coronary relaxation, an effect that may be related to the restoration of smooth muscle reactivity to NO and to an enhanced NO production by EETs (3, 18). Surprisingly, this was not accompanied by a restoration of myocardial perfusion. This may be related to the need for a higher duration of follow-up or to the fact that the classical EDH pathway, which could be not affected by t-AUCB, plays a role at this level. Nonetheless, t-AUCB, but not glibenclamide, prevented cardiac diastolic function, as shown by the improvement in LV compliance, together with opposing the development of cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis in HFD mice. These effects are probably related to the decrease in LV macrophages infiltration, inflammation, and oxidative stress, illustrated by the reduction in F4/80-positive cells and in NF-κB and NOX4 protein expressions, and to the increase in pAkt, which mediate some cardiac protective effects of EETs (3, 15, 20). In addition, an improvement in calcium homeostasis may help to prevent diastolic dysfunction, as recently suggested from experiments performed in cardiomyocytes isolated from hyperglycemic rats treated with another sEH inhibitor (9). Accordingly, one recent study showed that the genetic modulation of EET pathway through CYP450 epoxygenase overexpression protects streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice from the development of cardiac remodeling and dysfunction (16).

Conclusion

Altogether, these results show that the pharmacological inhibition of sEH reverses coronary endothelial dysfunction and prevents the early development of cardiac hypertrophy and diastolic dysfunction in a murine model of insulin resistance, beyond its glucose-lowering effect. This positive impact on cardiovascular damage, together with the improvement in metabolic homeostasis, prompts sEH inhibition as a novel and valuable therapeutic perspective in insulin-resistant states. At this time, sEH inhibitors have entered the first phases of clinical development, and our data strongly support the growing interest for this treatment in insulin resistant and type 2 diabetic patients.

GRANTS

This study was funded by a grant from the Fondation de France (2011-20459) and by a National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Superfund Basic Research Program grant (P42 ES04699).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Author contributions: C.R., M.B., R.C., N.H., D.C., D.G., L.N., E.L., C.M., I.R.-J., P.M., A.O.-P., and A.-M.M. performed experiments; C.R., R.C., N.H., D.C., D.G., L.N., E.L., C.M., I.R.-J., P.M., A.O.-P., A.-M.M., and J.B. analyzed data; C.R., D.G., C.M., A.-M.M., and V.R. edited and revised manuscript; C.R., M.B., R.C., N.H., D.C., D.G., L.N., E.L., C.M., P.M., A.O.-P., A.-M.M., V.R., and J.B. approved final version of manuscript; A.-M.M., V.R., and J.B. conception and design of research; J.B. interpreted results of experiments; J.B. prepared figures; J.B. drafted manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Alexandre Gueret, Julie Favre, Brigitte Dautreaux, Anaïs Dumesnil, and Annie Lejeune (Inserm U1096) for technical support; Dr. Hua Dong (University of California, Davis) for the quantification of t-AUCB in blood; and Stéphanie Chanon for technical assistance in cryostat sections of mouse liver and the genomic platform of INSERM 1060-CarMeN.

REFERENCES

- 1.Banquet S, Gomez E, Nicol L, Edwards-Lévy F, Henry JP, Cao R, Schapman D, Dautreaux B, Lallemand F, Bauer F, Cao Y, Thuillez C, Mulder P, Richard V, Brakenhielm E. Arteriogenic therapy by intramyocardial sustained delivery of a novel growth factor combination prevents chronic heart failure. Circulation 124: 1059–1069, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellien J, Iacob M, Remy-Jouet I, Lucas D, Monteil C, Gutierrez L, Vendeville C, Dreano Y, Mercier A, Thuillez C, Joannides R. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acids contribute with altered NO and endothelin-1 pathways to conduit artery endothelial dysfunction in essential hypertension. Circulation 125: 1266–1275, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bellien J, Joannides R, Richard V, Thuillez C. Modulation of cytochrome-derived epoxyeicosatrienoic acids pathway: a promising pharmacological approach to prevent endothelial dysfunction in cardiovascular diseases? Pharmacol Ther 131: 1–17, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Boudina S, Abel ED. Diabetic cardiomyopathy, causes and effects. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 11: 31–39, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Taeye BM, Morisseau C, Coyle J, Covington JW, Luria A, Yang J, Murphy SB, Friedman DB, Hammock BB, Vaughan DE. Expression and regulation of soluble epoxide hydrolase in adipose tissue. Obesity (Silver Spring) 18: 489–498, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.do Carmo JM, da Silva AA, Morgan J, Jim Wang YX, Munusamy S, Hall JE. Inhibition of soluble epoxide hydrolase reduces food intake and increases metabolic rate in obese mice. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 22: 598–604, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fuentes E, Fuentes F, Vilahur G, Badimon L, Palomo I. Mechanisms of chronic state of inflammation as mediators that link obese adipose tissue and metabolic syndrome. Mediators Inflamm 2013: 136584, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gao J, Bellien J, Gomez E, Henry JP, Dautreaux B, Bounoure F, Skiba M, Thuillez C, Richard V. Soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibition prevents coronary endothelial dysfunction in mice with renovascular hypertension. J Hypertens 29: 1128–1135, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guglielmino K, Jackson K, Harris TR, Vu V, Dong H, Dutrow G, Evans JE, Graham J, Cummings BP, Havel PJ, Chiamvimonvat N, Despa S, Hammock BD, Despa F. Pharmacological inhibition of soluble epoxide hydrolase provides cardioprotection in hyperglycemic rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 303: H853–H862, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hwang SH, Tsai HJ, Liu JY, Morisseau C, Hammock BD. Orally bioavailable potent soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibitors. J Med Chem 50: 3825–3840, 2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Iyer A, Kauter K, Alam MA, Hwang SH, Morisseau C, Hammock BD, Brown L. Pharmacological inhibition of soluble epoxide hydrolase ameliorates diet-induced metabolic syndrome in rats. Exp Diabetes Res 2012: 758614, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Laakso M. Cardiovascular disease in type 2 diabetes from population to man to mechanisms: the Kelly West Award Lecture 2008. Diabetes Care 33: 442–449, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Y, Dang H, Li D, Pang W, Hammock BD, Zhu Y. Inhibition of soluble epoxide hydrolase attenuates high-fat-diet-induced hepatic steatosis by reduced systemic inflammatory status in mice. PLoS One 7: e39165, 2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luo P, Chang HH, Zhou Y, Zhang S, Hwang SH, Morisseau C, Wang CY, Inscho EW, Hammock BD, Wang MH. Inhibition or deletion of soluble epoxide hydrolase prevents hyperglycemia, promotes insulin secretion, and reduces islet apoptosis. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 334: 430–438, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Luria A, Bettaieb A, Xi Y, Shieh GJ, Liu HC, Inoue H, Tsai HJ, Imig JD, Haj FG, Hammock BD. Soluble epoxide hydrolase deficiency alters pancreatic islet size and improves glucose homeostasis in a model of insulin resistance. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 108: 9038–9043, 2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma B, Xiong X, Chen C, Li H, Xu X, Li X, Li R, Chen G, Dackor RT, Zeldin DC, Wang DW. Cardiac-specific overexpression of CYP2J2 attenuates diabetic cardiomyopathy in male streptozotocin-induced diabetic mice. Endocrinology 154: 2843–2856, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mazzone T, Chait A, Plutzky J. Cardiovascular disease risk in type 2 diabetes mellitus: insights from mechanistic studies. Lancet 371: 1800–1809, 2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merabet N, Bellien J, Glevarec E, Nicol L, Lucas D, Jouet I, Bounoure F, Dreano Y, Wecker D, Thuillez C, Mulder P. Soluble epoxide hydrolase inhibition improves myocardial perfusion and function in experimental heart failure. J Mol Cell Cardiol 52: 660–666, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller AW, Dimitropoulou C, Han G, White RE, Busija DW, Carrier GO. Epoxyeicosatrienoic acid-induced relaxation is impaired in insulin resistance. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 281: H1524–H1531, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Morisseau C, Hammock BD. Impact of soluble epoxide hydrolase and epoxyeicosanoids on human health. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 53: 37–58, 2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Perriello G, Pampanelli S, Del Sindaco P, Lalli C, Ciofetta M, Volpi E, Santeu-sanio F, Brunetti P, Bolli GB. Evidence of increased systemic glucose production and gluconeogenesis in an early stage of NIDDM. Diabetes 46: 1010–1016, 1997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tabit CE, Chung WB, Hamburg NM, Vita JA. Endothelial dysfunction in diabetes mellitus: molecular mechanisms and clinical implications. Rev Endocr Metab Disord 11: 61–74, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tandon N, Ali MK, Narayan KM. Pharmacologic prevention of microvascular and macrovascular complications in diabetes mellitus: implications of the results of recent clinical trials in type 2 diabetes. Am J Cardiovasc Drugs 12: 7–22, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xu X, Zhao CX, Wang L, Tu L, Fang X, Zheng C, Edin ML, Zeldin DC, Wang DW. Increased CYP2J3 expression reduces insulin resistance in fructose-treated rats and db/db mice. Diabetes 59: 997–1005, 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang LN, Vincelette J, Chen D, Gless RD, Anandan SK, Rubanyi GM, Webb HK, MacIntyre DE, Wang YX. Inhibition of soluble epoxide hydrolase attenuates endothelial dysfunction in animal models of diabetes, obesity and hypertension. Eur J Pharmacol 654: 68–74, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao X, Dey A, Romanko OP, Stepp DW, Wang MH, Zhou Y, Jin L, Pollock JS, Webb RC, Imig JD. Decreased epoxygenase and increased epoxide hydrolase expression in the mesenteric artery of obese Zucker rats. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 288: R188–R196, 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]