The frequency to which quality of life (QoL) is specified as an outcome in protocols of cancer trials and subsequently published was unknown. In a sample of trials approved by research ethics committees, half of trials specified QoL outcomes but only 20% reported QoL outcomes after 10 or more years. Highly relevant information for decision making is often unavailable.

Keywords: neoplasms, quality of life, publication bias, cohort studies, ethics committees, randomized controlled trials as topic

Abstract

Background

Information about the impact of cancer treatments on patients' quality of life (QoL) is of paramount importance to patients and treating oncologists. Cancer trials that do not specify QoL as an outcome or fail to report collected QoL data, omit crucial information for decision making. To estimate the magnitude of these problems, we investigated how frequently QoL outcomes were specified in protocols of cancer trials and subsequently reported.

Design

Retrospective cohort study of RCT protocols approved by six research ethics committees in Switzerland, Germany, and Canada between 2000 and 2003. We compared protocols to corresponding publications, which were identified through literature searches and investigator surveys.

Results

Of the 173 cancer trials, 90 (52%) specified QoL outcomes in their protocol, 2 (1%) as primary and 88 (51%) as secondary outcome. Of the 173 trials, 35 (20%) reported QoL outcomes in a corresponding publication (4 modified from the protocol), 18 (10%) were published but failed to report QoL outcomes in the primary or a secondary publication, and 37 (21%) were not published at all. Of the 83 (48%) trials that did not specify QoL outcomes in their protocol, none subsequently reported QoL outcomes. Failure to report pre-specified QoL outcomes was not associated with industry sponsorship (versus non-industry), sample size, and multicentre (versus single centre) status but possibly with trial discontinuation.

Conclusions

About half of cancer trials specified QoL outcomes in their protocols. However, only 20% reported any QoL data in associated publications. Highly relevant information for decision making is often unavailable to patients, oncologists, and health policymakers.

introduction

Information about the impact of cancer treatments on patients' quality of life (QoL) is of paramount importance to patients and treating oncologists. Lack of QoL outcomes complicates decision making, especially in palliative situations when the expected survival benefit of a specific therapy may be small but its impact on QoL essential. Therefore, major funding and regulatory agencies, policymakers, and patient organizations increasingly demand measurement of QoL outcomes in clinical studies [1, 2].

In spite of the availability of valid instruments such as the European Organization of Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30) or the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) [3, 4], publications of randomized clinical trials (RCTs) involving cancer patients often do not report on QoL outcomes. For instance, only 41% of advanced-stage lung cancer trials published between 2006 and 2008 reported a QoL outcome [5]. Instead, cancer trials typically focus on survival or tumour size as their primary outcome [5–7], a trend that has constantly increased over time [6, 7]. In addition, reporting quality of QoL outcomes was found to be highly variable [8, 9], and recent initiatives have provided guidance in an effort to improve and harmonize reporting practices [10, 11].

However, the magnitude of two other fundamental problems, the non-specification of QoL as an outcome and failure to report collected QoL data, is unknown. If cancer trials do not specify QoL as an outcome or fail to report collected QoL data, crucial information is not available for decision making and the risk of misguidance due to selective reporting increases.

The objective of this study was to systematically compare the planning of QoL outcomes in RCT protocols involving cancer patients with subsequent reporting in publications. In addition, we explored risk factors for non-reporting of planned QoL outcomes.

methods

study design

This is an ancillary analysis of a large retrospective cohort of RCTs that were approved by six research ethics committees (RECs) in Switzerland (Basel, Lausanne, Zurich, and Lucerne), Germany (Freiburg), and Canada (Hamilton) between 2000 and 2003 [12–15]. All RECs but one are responsible for human research in large university centres and additional hospitals in their respective catchment areas; one (Lucerne) covers an academic teaching hospital. As a convenience sample, we approached them through existing contacts.

In the present study, we included RCT protocols that involved patients with solid or haematological malignancies. We excluded protocols of RCTs that: (i) compared only different doses or routes of administration of the same drug (early dose-finding studies), (ii) were never started, or (iii) were still on-going as of February 2014. We included full peer-reviewed journal publications of corresponding RCT protocols and excluded research letters, letters to the editor, or conference abstracts.

We conducted comprehensive searches of electronic databases to locate any associated publications. In addition, we hand-searched the files of RECs, and the RECs sent survey questionnaires to study investigators in case of missing information. Our search strategy is reported elsewhere [12]. Two investigators (BK and SS) searched independently and in duplicate for secondary publications reporting additional QoL results. The last update of the search was carried out in February 2014.

definitions

We accepted at face value all QoL outcomes reported as such by investigators of individual trials. We included QoL outcomes irrespective of whether they were measured by multidimensional questionnaires (e.g. EORTC QLQ-C30) or by direct valuation (e.g. visual analogue scale) and whether they were generic or disease specific.

We assessed RCT protocols for industry or investigator sponsorship using the following criteria: the protocol clearly named the sponsor, displayed a company or institution logo prominently, mentioned affiliations of protocol authors, included statements about data ownership or publication rights, or included statements about full funding by industry or public funding agencies [12, 13].

We considered an RCT discontinued if the investigators indicated discontinuation with a reason in their correspondence with the REC, in a journal publication, or in their response to our survey. If we could not elucidate the reason for RCT discontinuation or if poor participant recruitment was mentioned, we used a pre-specified cut-off of <90% of achieved target sample size to classify discontinuation [12, 13].

data extraction

Investigators trained in research methodology independently extracted data from eligible RCT protocols and from correspondence between the RECs and the local investigators that was documented in the REC files. Thirty-nine percent of protocols from cancer RCTs were extracted in duplicate as an initial calibration process to maximize the consistency of data extraction across reviewers; all corresponding publications were extracted in duplicate. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or by third-party adjudication.

Specifically for this project, two oncologists (KC and BK) independently assessed the pairs of protocols and corresponding publications for agreement with respect to the type of QoL instrument(s). For each RCT, they judged independently whether the QoL results were: (i) reported for all subdomains of all specified instruments, (ii) reported but not for all subdomains or instruments, (iii) reported but using completely different instruments than specified, or (iv) not reported at all. In addition, the same two oncologists independently judged the aim of therapy (i.e. palliative, curative, mix, treating side-effects of cancer therapy, unclear) and stage of malignancy (i.e. metastatic, advanced, localized, mix, unclear). They resolved disagreements by consensus or by third-party adjudication.

statistical analysis

For binary data, we summarized results as frequencies and proportions and for continuous data as medians and interquartile ranges (IQRs). We present the results as proportions and associated 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) using the Jeffreys method [16]. We used the χ2 test to explore differences in proportions. Using complete case multivariable logistic regression, we tested the association between the dependent variable ‘reporting of any QoL outcomes’ and the following four independent variables: (i) discontinued RCT (versus completed); (ii) investigator sponsorship (versus industry); (iii) single-centre status (versus multicentre); and (iv) sample size (continuous, in increments of 100). These variables are known to be associated with non-publication of RCTs [13], and industry sponsorship is known to be associated with selective outcome reporting [17]. Therefore, we hypothesized that these variables might also be associated with failure to report pre-specified QoL outcomes. We limited our regression model to the subset of trials that pre-specified a QoL outcome in their protocol. We carried out sensitivity analyses using (i) the alternative outcome definition ‘reporting of QoL outcomes as pre-specified in protocol’ and the same independent variables and (ii) multiple imputations for missing information about trial discontinuation (missing in seven RCTs) [18]. We expressed associations as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs and considered two-sided P ≤ 0.05 as significant. We used R version 3.1.0 (www.r-project.org) for all analyses.

results

protocol and publication characteristics

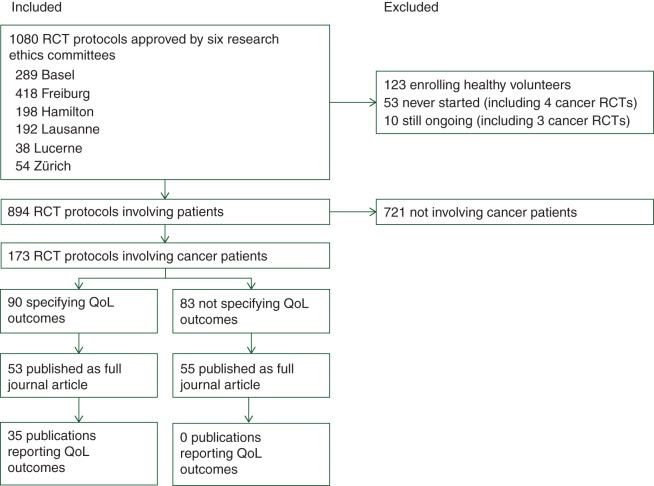

Of 894 RCT involving patients, 173 (19%) enrolled patients with cancer (Figure 1). Most cancer trials were multicentre RCTs investigating palliative drug treatments in patients with solid malignancies, half of the trials were industry-sponsored (87, 50%), and one-third were discontinued (50, 34%). The most frequent reason for discontinuation was poor recruitment (22, 13%) (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Study selection. RCT, randomized clinical trial; REC, research ethics committee; QoL, quality of life.

Table 1.

Characteristics of cancer RCTs

| Total (N = 173) | Investigator-sponsored (N = 86) | Industry-sponsored (N = 87) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sample size, median (IQR) | 318 (132–685) | 330 (200–624) | 300 (125–690) |

| Multicentre study | 168 (97%) | 83 (97%) | 85 (98%) |

| Superiority design | 141 (82%) | 74 (86%) | 67 (77%) |

| Haematologic malignancy | 40 (23%) | 29 (34%) | 11 (13%) |

| Solid malignancy | 133 (77%) | 57 (66%) | 76 (87%) |

| Metastatic stage | 81 (47%) | 27 (31%) | 54 (62%) |

| Advanced stage | 25 (15%) | 12 (14%) | 13 (15%) |

| Localized stage | 3 (2%) | 2 (2%) | 1 (1%) |

| Mix of stages | 12 (7%) | 6 (7%) | 6 (7%) |

| Unclear stage(s) | 12 (7%) | 10 (12%) | 2 (2%) |

| Type of cancer (only categories ≥5%) | |||

| Breast cancer | 33 (19%) | 12 (14%) | 21 (24%) |

| Non-small-cell lung cancer | 16 (9%) | 2 (2%) | 14 (16%) |

| Colorectal cancer | 11 (6%) | 3 (4%) | 8 (9%) |

| Non-Hodgkin lymphoma | 9 (5%) | 6 (7%) | 3 (3%) |

| Pancreatic cancer | 8 (5%) | 3 (4%) | 5 (6%) |

| Drug intervention | 164 (95%) | 78 (91%) | 86 (99%) |

| Therapy intent | |||

| Palliative | 112 (65%) | 49 (57%) | 63 (72%) |

| Curative | 35 (20%) | 22 (26%) | 13 (15%) |

| Mix | 2 (1%) | 2 (2%) | 0 |

| Treating side-effects of cancer therapy | 16 (9%) | 7 (8%) | 9 (10%) |

| Unclear | 8 (5%) | 6 (7%) | 2 (2%) |

| Type of primary outcome | |||

| Overall survival | 49 (28%) | 23 (27%) | 26 (30%) |

| Progression- or disease-free survival | 51 (30%) | 25 (29%) | 26 (30%) |

| Tumour response | 23 (13%) | 11 (13%) | 12 (14%) |

| Symptom control | 17 (10%) | 8 (9%) | 9 (10%) |

| Quality of life | 2 (1%) | 0 | 2 (3%) |

| Other | 25 (14%) | 15 (17%) | 10 (11%) |

| Not specified | 6 (3%) | 4 (5%) | 2 (2%) |

| Trial completion status | |||

| Completed | 105 (61%) | 51 (59%) | 54 (62%) |

| Discontinued | 59 (34%) | 31 (36%) | 28 (32%) |

| Poor recruitment | 22 (13%) | 13 (15%) | 9 (10%) |

| Futility | 15 (9%) | 6 (7%) | 9 (10%) |

| Administrative | 6 (4%) | 2 (2%) | 4 (5%) |

| Harm | 6 (4%) | 3 (4%) | 3 (3%) |

| Benefit | 5 (3%) | 5 (6%) | 0 |

| External evidence | 2 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) |

| Other reason | 2 (1%) | 1 (1%) | 1 (1%) |

| Unclear reason | 1 (1%) | 0 | 1 (1%) |

| Completion status unclear | 9 (5%) | 4 (5%) | 5 (6%) |

RCT, randomized clinical trial; IQR, interquartile range.

Of the 173 cancer trials, 108 (62%) were subsequently published as full journal article; 52 (30%) cancer RCTs were not published at all, and 13 (8%) were published but not as full journal articles. Publication dates ranged between 2003 and 2013, with a median at 2007. The median time between ethical approval and first full journal publication was 5.7 years (IQR, 4.5–7.8 years, range 0.7–12.1 years).

planning of QoL outcomes

The most frequently specified primary outcomes were survival and tumour response (Table 1). Ninety of 173 (52%, 95% CI 45% to 59%) cancer trial protocols reported the measurement of QoL outcomes. QoL was defined as the sole primary outcome in one protocol, as a co-primary outcome in a second, and as a secondary outcome in 88 protocols. The remaining 83 (48%, 95% CI 41% to 55%) RCTs failed to specify a QoL outcome in their protocol (and none of these reported a QoL outcome in subsequent publications). The proportion of RCT specifying QoL outcomes did not differ significantly across RECs (supplementary Table 1, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Most RCT protocols (57, 63%) specified one QoL instrument; the remaining specified two (26%) or three instruments (3%), or the number of instruments was unclear (8%). The most common QoL instruments to be used were the EORTC QLQ (core questionnaire or modules) in 47 of 90 RCTs (52%), the FACT (core questionnaire or modules) in 19 RCTs (21%), and the EuroQoL-5D (EQ-5D) in 5 RCTS (6%). Other instruments were used in 9 RCTs (10%), and instruments were not specified in 15 (17%).

The frequency of planning of QoL outcomes did not differ significantly between investigator-sponsored (47/86, 55%) and industry-sponsored (43/87, 49%) RCTs (P = 0.49). Of 112 RCT protocols that investigated palliative treatments, 65 (57%) planned to measure QoL.

reporting of QoL outcomes

Of the 173 cancer RCTs, 35 (20%, 95% CI 15% to 27%) reported QoL outcomes in a corresponding publication (including 6 secondary publications); of these, 31 (18%, 95% CI 13% to 24%) reported QoL outcomes exactly as specified and 4 (2%, 95% CI 1% to 5%) modified reporting from the protocol (3 reported only one of two specified instruments; 1 reported two completely different instruments, none reported subscales only). Of the 173 trials, 37 (21%, 95% CI 16% to 28%) specified QoL outcomes in the protocol but remained unpublished after a median follow-up of 11.6 years (range, 8.8–12.6 years), and 18 (10%, 95% CI 7% to 16%) specified QoL outcomes but failed to report any QoL outcomes in subsequent publications (Table 2).

Table 2.

Planning and reporting of QoL outcomes

| Total (N = 173) | Investigator-sponsored (N = 86) | Industry-sponsored (N = 87) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| QoL specified in protocol | 90 (52%) | 47 (55%) | 43 (49%) |

| Published | 53 (31%) | 27 (31%) | 26 (30%) |

| QoL reported | 35 (20%) | 16 (19%) | 19 (22%) |

| Instruments as specified | 31 (18%) | 16 (19%) | 15 (17%) |

| Only one of two instruments | 3 (2%) | 0 | 3 (3%) |

| Two completely different instruments | 1 (1%) | 0 | 1 (1%) |

| QoL not reported | 18 (10%) | 11 (13%) | 7 (8%) |

| Not published | 37 (21%) | 20 (23%) | 17 (20%) |

| QoL not specified in protocol | 83 (48%) | 39 (45%) | 44 (51%) |

| Published | 55 (32%) | 26 (30%) | 29 (33%) |

| QoL not reported | 55 (32%) | 26 (30%) | 29 (33%) |

| Not published | 28 (16%) | 13 (15%) | 15 (17%) |

QoL, quality of life.

risk factors for non-reporting of QoL outcomes

Using complete cases only, none of the independent factors we explored (investigator sponsorship, sample size, trial discontinuation, or single-centre status) was significantly associated with failure to report any QoL outcomes (Table 3). This finding was confirmed in a sensitivity analysis with the alternative outcome ‘failure to report QoL outcomes exactly as specified in protocol’ (supplementary Table 2, available at Annals of Oncology online). When we used multiple imputations, trial discontinuation was significantly associated with failure to report any QoL outcome (OR 2.88, 95% CI 1.00–8.29) and failure to report QoL outcomes exactly as specified in protocol (OR 3.20, 95% CI 1.07–9.64) (supplementary Tables 3 and 4, available at Annals of Oncology online).

Table 3.

Risk factors for non-reporting of QoL outcomes

| Univariable effect |

Multivariable effect |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | P | Adjusted odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | P | |

| Planned target sample sizea | 0.98 (0.91–1.06) | 0.63 | 1.00 (0.93–1.08) | 0.95 |

| Discontinued RCT (versus completed) | 2.62 (0.95–7.20) | 0.062 | 2.65 (0.93–7.52) | 0.067 |

| Single-centre status (versus multicentre) | 1.48 (0.13–16.98) | 0.75 | 1.16 (0.13–20.31) | 0.71 |

| Investigator sponsorship (versus industry) | 1.66 (0.69–4.00) | 0.26 | 1.56 (0.62–3.91) | 0.34 |

Of the 90 RCT that pre-specified QoL outcomes, we excluded seven RCTs with unclear completion status (none of them reporting any QoL outcomes) thus leaving 83 RCTs and a total of 48 events for analysis.

See supplementary Tables 1–3, available at Annals of Oncology online, for sensitivity analyses.

aIn increments of 100.

RCT, randomized clinical trial.

discussion

main findings

Approximately half of cancer RCTs specified QoL outcomes in their protocols; however, only 20% reported any QoL data in associated publications. The main reason for the failure to report QoL outcomes was non-specification in the protocol (48%), followed by non-publication of the trial (21%), and non-reporting of QoL outcomes reported in protocols in subsequent publications (10%). In other words, if QoL outcomes were specified at all, most of them were not reported. Failure to report pre-specified QoL outcomes was possibly associated with trial discontinuation but not with sponsorship, sample size, or single-centre status.

strength and limitations

The data for the present study were collected as part of a large international cohort involving six RECs that allowed us full access to RCT protocols and filed correspondence [12, 13]. As outlined previously [19, 20]. Comparing protocols with subsequent publications is the most reliable method to evaluate the reporting of RCTs. We identified corresponding publications by systematically searching REC files, multiple electronic databases, and by contacting trialists through the REC in charge [12]. We focused on protocols that had been approved 10 or more years after REC approval to minimize the number of on-going or unpublished RCTs [13]. We involved only trained methodologists in data abstraction and two oncologists who independently categorized the patient populations regarding the intention of treatment.

Our study has limitations. Because we extracted a total of 1017 RCT protocols and corresponding publications for the main project [13], we used single data extraction for 61% of cancer trial protocols due to limited resources, thereby potentially introducing extraction errors. However, we used pre-piloted extraction forms with detailed written instructions, conducted formal calibration exercises with all data extractors, and measured agreement between independent data extractors from a random sample of protocols at several points during the process. Agreement was good with no more than two discrepancies in 30 extracted key variables [13]. We used a convenience sample of six RECs in three countries. We cannot claim that these are representative for other RECs in these or other countries; however, to our knowledge, they are not in any way idiosyncratic.

We implicitly assumed that collection of QoL outcomes would have been important in all included cancer trials. Most trials from our sample included patients who were treated with a palliative intention; evaluating the impact of experimental treatments on QoL is more than appropriate in these settings. In addition, we excluded dose-finding studies that typically do not include QoL as an outcome. However, we acknowledge that there may be instances where collection of QoL outcomes in cancer patients may be less important, e.g. when treating acute life-threatening conditions (six RCTs) or if the QoL outcomes related to this intervention have been previously well described (which is rather unlikely). We decided a priori to include any QoL instrument at face value, which is irrespective of its validity in a specific setting. We felt that further sub-division into validated, non-validated, and unclear would add an additional level of complexity but would be unlikely to affect our conclusions.

Finally, we did not ask investigators for unreported study results or the reasons why a study or a pre-specified outcome was not published. Therefore, we could not investigate whether, for example the level of statistical significance influenced the decision to report the outcome in the publication [17].

comparison with other studies

Our study confirms the previously reported large extent of under-reporting of RCT outcomes [17]. To our knowledge, this is the first study to assess planning of QoL outcomes in RCTs protocols involving cancer patients and the subsequent concordance of reporting.

We can only speculate about the reasons why investigators of oncological studies initially plan to measure QoL but then often do not report QoL outcome data. Earlier studies hypothesized that investigators may encounter methodological difficulties with analysing or interpreting QoL outcomes [21], or may distrust the integrity of their QoL data due to inconsistent collection or substantial missingness of data [22]. It is unlikely that investigator did not collect any data for the QoL outcomes that they specified in the protocol; a recent survey of RCT investigators suggested that in only 13 of 419 RCTs (3%) investigators did not collect data for pre-specified outcomes [23].

We assume that the most likely reasons for not reporting of QoL outcomes in cancer RCTs are similar to those that have been repeatedly identified by other studies: data for secondary outcomes were not analysed after negative main results [23], or findings might be inconclusive or unfavourable [17]. One reason for inconclusive QoL results and subsequent non-publication may include premature trial discontinuation as suggested by our regression analysis. Finally, the failure to report QoL outcomes may also be motivated by reasons such as journal space restrictions, data being perceived as uninteresting, or trialists' lack of awareness of the implications [23, 24].

Our data did not support the finding of a smaller study (25 cancer RCTs) that cancer RCTs recruit more successfully than other RCTs [25]. About a third of cancer RCTs were prematurely discontinued and 13% because of poor recruitment. These proportions were similar to previously reported findings in RCTs of all disciplines of which 28% were prematurely discontinued and 11% due to poor recruitment [13].

implications

Failure to report pre-specified outcomes can seriously bias published evidence [26], especially because positive findings are more likely to be reported than negative findings [17]. For instance, a meta-analysis of cancer trials suggested that administration of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents prolonged survival, while an updated individual patient data meta-analysis that included previously unpublished outcome data showed no significant effect [27].

Given the importance of QoL outcomes for cancer patients and the risk of bias introduced by selective reporting, we believe that the oncology community should take action to address this problem. A number of solutions are possible; one would be that journals request protocols to accompany all manuscript submissions and ensure concordance between planned and reported outcomes.

conclusion

Only ∼20% of cancer RCTs approved by RECs subsequently reported QoL outcomes. Most cancer RCTs either never specified QoL outcomes, did so but were never published, or failed to report pre-specified QoL outcomes in their corresponding publications. Consequently, highly relevant information is often unavailable to users of cancer research including cancer patients, oncologists, and health policymakers.

ethical approval

This study was approved by the participating research ethics committees, or if no ethical approval was required this was explicitly stated.

funding

This work was supported by the Swiss National Science Foundation (320030_133540/1 to MB) and the German Research Foundation (EL 544/1-2 to EVE); Santésuisse and the Gottfried and Julia Bangerter-Rhyner-Foundation (MB, AN, VG, HR, LGH, HCB); Brocher Foundation (EVE), New Investigator Award from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research and Canadian Chiropractic Research Foundation (JWB); Research Early Career Award from Hamilton Health Sciences Foundation (Jack Hirsh Fellowship) (DM); Unrestricted grants from the Academy of Finland, Finnish Cultural Foundation, Finnish Medical Foundation, Jane and Aatos Erkko Foundation, and Sigrid Jusélius Foundation (KAOT); Research Early Career Award from Hamilton Health Sciences (JY); RR is an employee of F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd since 1 May 2014. The present study was conducted before Rosenthal joined F. Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd and has no connection to her employment by the company.

role of the sponsors

The Swiss National Science Foundation, the German Research Foundation, and the Brocher Foundation had no role in the design and conduct of the study; the collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; the preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

disclosure

The authors have declared no conflicts of interest.

Supplementary Material

acknowledgements

We thank the chairs and staff of participating Research Ethics Committees from Switzerland (Basel, Lausanne, Zurich, Lucerne), Germany (Freiburg), and Canada (Hamilton) for their continuous support and cooperation.

appendix

DISCO Study group

S. Schandelmaier1,22, K. Conen30, E. von Elm3, J. J. You2, 14, A. Blümle4, Y. Tomonaga5, R. Saccilotto1, A. Amstutz1, T. Bengough28, J. J. Meerpohl4, M. Stegert1, K. K. Olu1, K. A. O. Tikkinen2,15, I. Neumann2,16, A. Carrasco-Labra2,25, M. Faulhaber2, S. M. Mulla2, D. Mertz2,14,26, E. A. Akl2,18,19, X. Sun2,23, D. Bassler6, J. W. Busse2,20,27, I. Ferreira-González7, F. Lamontagne8, A. Nordmann1, V. Gloy1,13, H. Raatz1, L. Moja9, R. Rosenthal10, S. Ebrahim2,12,20,21, P. O. Vandvik11, B. C. Johnston2,12,24, M. A. Walter13, B. Burnand3, M. Schwenkglenks5, L. G. Hemkens1, H. C. Bucher1, G. H. Guyatt2, M. Briel1,2,29 and B. Kasenda1,30,31

1Basel Institute for Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, University Hospital of Basel, Switzerland

2Department of Clinical Epidemiology and Biostatistics, McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada

3Cochrane Switzerland, Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine (IUMSP), Lausanne University Hospital, Lausanne, Switzerland

4German Cochrane Centre, Medical Center–University of Freiburg, Freiburg, Germany

5Epidemiology, Biostatistics and Prevention Institute, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

6Department of Neonatolgy, University Hospital Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland

7Epidemiology Unit, Department of Cardiology, Vall d'Hebron Hospital and CIBER de Epidemiología y Salud Publica (CIBERESP), Barcelona, Spain

8Centre de Recherche Clinique du Centre Hospitalier Universitaire de Sherbrooke, Université de Sherbrooke, Sherbrooke, Canada

9IRCCS Orthopedic Institute Galeazzi, Milan, Italy

10Department of Surgery, University Hospital Basel, Switzerland

11Department of Medicine, Innlandet Hospital Trust-Division Gjøvik, Oppland, Norway

12Department of Anesthesia and Pain Medicine, Hospital for Sick Children Research Institute, Hospital for Sick Children, Toronto, Canada

13Institute of Nuclear Medicine, University Hospital Bern, Bern, Switzerland

14Department of Medicine, McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada

15Departments of Urology and Public Health, Helsinki University Hospital and University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland

16Department of Internal Medicine, Pontificia Universidad Catolica de Chile, Santiago, Chile

18Department of Internal Medicine, American University of Beirut, Beirut, Lebanon

19Department of Medicine, State University of New York at Buffalo, Buffalo, USA

20Department of Anesthesia, McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada

21Stanford Prevention Research Center, Stanford University, Stanford, USA

22Academy of Swiss Insurance Medicine, University Hospital Basel, Basel, Switzerland

23Chinese Evidence-Based Medicine Center, West China Hospital, Sichuan University, Chengdu, China

24Institute of Health Policy, Management and Evaluation, University of Toronto, Toronto, Canada

25Evidence-Based Dentistry Unit, Faculty of Dentistry, Universidad de Chile, Santiago, Chile

26Michael G. DeGroote Institute for Infectious Diseases Research, McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada

27Michael G. DeGroote Institute for Pain Research and Care, McMaster University, Hamilton, Canada

28Department of Health and Society, Austrian Federal Institute for Health Care, Vienna, Austria

29Department of Clinical Research, University of Basel, Switzerland

30Department of Oncology, University Hospital of Basel, Switzerland

31Department of Medical Oncology, Royal Marsden Hospital, London, UK

Contributor Information

Collaborators: the DISCO study group, S. Schandelmaier, K. Conen, E. von Elm, J. J. You, A. Blümle, Y. Tomonaga, R. Saccilotto, A. Amstutz, T. Bengough, J. J. Meerpohl, M. Stegert, K. K. Olu, K. A. O. Tikkinen, I. Neumann, A. Carrasco-Labra, M. Faulhaber, S. M. Mulla, D. Mertz, E. A. Akl, X. Sun, D. Bassler, J. W. Busse, I. Ferreira-González, F. Lamontagne, A. Nordmann, V. Gloy, H. Raatz, L. Moja, R. Rosenthal, S. Ebrahim, P. O. Vandvik, B. C. Johnston, M. A. Walter, B. Burnand, M. Schwenkglenks, L. G. Hemkens, H. C. Bucher, G. H. Guyatt, M. Briel, and B. Kasenda

references

- 1.Basch E, Abernethy AP, Mullins CD et al. Recommendations for incorporating patient-reported outcomes into clinical comparative effectiveness research in adult oncology. J Clin Oncol 2012; 30(34): 4249–4255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lipscomb J, Gotay CC, Snyder CF. Patient-reported outcomes in cancer: a review of recent research and policy initiatives. CA Cancer J Clin 2007; 57(5): 278–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Luckett T, King MT, Butow PN et al. Choosing between the EORTC QLQ-C30 and FACT-G for measuring health-related quality of life in cancer clinical research: issues, evidence and recommendations. Ann Oncol 2011; 22(10): 2179–2190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.King MT, Bell ML, Costa D et al. The Quality of Life Questionnaire Core 30 (QLQ-C30) and Functional Assessment of Cancer-General (FACT-G) differ in responsiveness, relative efficiency, and therefore required sample size. J Clin Epidemiol 2014; 67(1): 100–107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Conter HJMD, Ruchira Sengupta MAS, Devidas Menon PD et al. Current use of health-related quality of life outcomes in advanced-stage lung cancer clinical trials. Univ Tor Med J 2011; 88(2): 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Booth CM, Cescon DW, Wang L et al. Evolution of the randomized, controlled trial in oncology over three decades. J Clin Oncol 2008; 26(33): 5458–5464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kay A, Higgins J, Day AG et al. Randomized controlled trials in the era of molecular oncology: methodology, biomarkers, and end points. Ann Oncol 2012; 23(6): 1646–1651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Joly F, Vardy J, Pintilie M, Tannock IF. Quality of life and/or symptom control in randomized clinical trials for patients with advanced cancer. Ann Oncol 2007; 18(12): 1935–1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Brundage M, Bass B, Davidson J et al. Patterns of reporting health-related quality of life outcomes in randomized clinical trials: implications for clinicians and quality of life researchers. Qual Life Res 2011; 20(5): 653–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Calvert M, Blazeby J, Altman DG et al. Reporting of patient-reported outcomes in randomized trials: the consort pro extension. JAMA 2013; 309(8): 814–822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brundage M, Blazeby J, Revicki D et al. Patient-reported outcomes in randomized clinical trials: development of ISOQOL reporting standards. Qual Life Res 2013; 22(6): 1161–1175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kasenda B, von Elm EB, You J et al. Learning from failure—rationale and design for a study about discontinuation of randomized trials (DISCO study). BMC Med Res Methodol 2012; 12(1): 131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kasenda B, von Elm E, You J et al. Prevalence, characteristics, and publication of discontinued randomized trials. JAMA 2014; 311(10): 1045–1051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kasenda B, Schandelmaier S, Sun X et al. Subgroup analyses in randomised controlled trials: cohort study on trial protocols and journal publications. BMJ 2014; 349: g4539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rosenthal R, Kasenda B, Dell-Kuster S et al. Completion and publication rates of randomized controlled trials in surgery: an empirical study. Ann Surg 2015; 262(1): 68–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Brown LD, Cai TT, DasGupta A. Interval estimation for a binomial proportion. Stat Sci 2001; 16(2): 101–133. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dwan K, Gamble C, Williamson PR, Kirkham JJ. Systematic review of the empirical evidence of study publication bias and outcome reporting bias—an updated review. PLoS One 2013; 8(7): e66844. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kenward MG, Carpenter J. Multiple imputation: current perspectives. Stat Methods Med Res 2007; 16(3): 199–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chan A-W. Bias, spin, and misreporting: time for full access to trial protocols and results. PLoS Med 2008; 5(11): e230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dwan K, Altman DG, Cresswell L et al. Comparison of protocols and registry entries to published reports for randomised controlled trials. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011; 19(1): MR000031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sanders C, Egger M, Donovan J et al. Reporting on quality of life in randomised controlled trials: bibliographic study. BMJ 1998; 317(7167): 1191–1194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kyte D, Ives J, Draper H et al. Inconsistencies in quality of life data collection in clinical trials: a potential source of bias? Interviews with research nurses and trialists. PLoS One 2013; 8(10): e76625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smyth RMD, Kirkham JJ, Jacoby A et al. Frequency and reasons for outcome reporting bias in clinical trials: interviews with trialists. BMJ 2011; 342: c7153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chan A-W, Altman DG. Identifying outcome reporting bias in randomised trials on PubMed: review of publications and survey of authors. BMJ 2005; 330(7494): 753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Campbell MK, Snowdon C, Francis D et al. Recruitment to randomised trials: strategies for trial enrollment and participation study. The STEPS study. Health Technol Assess 2007; 11(48): iii, ix–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kirkham JJ, Dwan KM, Altman DG et al. The impact of outcome reporting bias in randomised controlled trials on a cohort of systematic reviews. BMJ 2010; 340: c365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tonia T, Schwarzer G, Bohlius J. Cancer, meta-analysis and reporting biases: the case of erythropoiesis-stimulating agents. Swiss Med Wkly 2013; 143: w13776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.