Abstract

Extracellular vesicles (EVs) produced by a sulfur-reducing, hyperthermophilic archaeon, “Thermococcus onnurineus” NA1T, were purified and characterized. A maximum of four EV bands, showing buoyant densities between 1.1899 and 1.2828 g cm−3, were observed after CsCl ultracentrifugation. The two major EV bands, B (buoyant density at 25°C [ρ25] = 1.2434 g cm−3) and C (ρ25 = 1.2648 g cm−3), were separately purified and counted using a qNano particle analyzer. These EVs, showing different buoyant densities, were identically spherical in shape, and their sizes varied from 80 to 210 nm in diameter, with 120- and 190-nm sizes predominant. The average size of DNA packaged into EVs was about 14 kb. The DNA of the EVs in band C was sequenced and assembled. Mapping of the T. onnurineus NA1T EV (ToEV) DNA sequences onto the reference genome of the parent archaeon revealed that most genes of T. onnurineus NA1T were packaged into EVs, except for an ∼9.4-kb region from TON_0536 to TON_0544. The absence of this specific region of the genome in the EVs was confirmed from band B of the same culture and from bands B and C purified from a different batch culture. The presence of the 3′-terminal sequence and the absence of the 5′-terminal sequence of TON_0536 were repeatedly confirmed. On the basis of these results, we hypothesize that the unpackaged part of the T. onnurineus NA1T genome might be related to the process that delivers DNA into ToEVs and/or the mechanism generating the ToEVs themselves.

INTRODUCTION

The production of extracellular vesicles (EVs) is widespread among all three domains of life: Eukaryota, Bacteria, and Archaea (1). Within the Archaea, EVs are produced by hyperthermophiles such as Sulfolobus species (2, 3), Ignicoccus spp. (4) in the Crenarchaeota, and Thermococcus kodakarensis (5) in the Euryarchaeota. Archaeal EVs released by Sulfolobus species range from 90 to 230 nm in diameter and contain membrane lipids and S-layer proteins derived from the parent archaeal cell surface. An extensive study on the presence of EVs in cultures of hyperthermophilic archaea (order Thermococcales), analyzed by electron microscopy, revealed that most strains of Thermococcus and Pyrococcus produced various types of spherical membrane vesicles (6). Membrane vesicles were usually spherical in shape; however, unusual structures such as filaments, chains of pearls, and others were also observed in various sizes from 10 to 20 nm to 200 to 300 nm. Chiura reported a high level of vesicle production (ca. 3 × 1012 liter−1) from a hyperthermophilic archaeon, T. kodakarensis, which had been isolated from a hydrothermal vent, after 480 h of culture at 70°C (5).

Since the first reported observation of microbial outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) from Vibrio cholerae about 50 years ago (7), the production of vesicles from microbial cells and their features have been described under various names, such as OMV, membrane vesicle or microvesicle (MV), virus-like particle or vesicle (VLP or VLV), vector particle (VP), and so on (5, 6, 8, 9). Numerous functions have been attributed to these vesicles by several investigators. It is now well known that EVs consist of proteins, lipids, lipopolysaccharides, and nucleic acids (both DNA and RNA), the same as the building materials of the parent organisms producing the EVs. Gram-negative bacteria produce OMVs that contain biologically active proteins and perform diverse biological processes (9, 10). Unlike other secretion mechanisms, OMVs enable bacteria to secrete insoluble molecules in addition to, and complexed with, soluble material. OMVs allow enzymes to reach distant targets in a concentrated, protected, and targeted form. OMVs also play roles in bacterial survival. Their production is a bacterial stress response and important for nutrient acquisition, biofilm development, and pathogenesis (9).

Vesicles carrying chromosomal and/or plasmid DNA have been reported from Gram-negative bacteria such as Escherichia, Haemophilus, Neisseria, Pseudomonas (10, 11), Ahrensia, and Pseudoalteromonas species (12), the cyanobacterium Prochlorococcus (13), and archaea such as Thermococcales strains, including T. kodakarensis and T. nautilus (5, 14, 15). DNA was determined to be in the interior of the vesicles by using a DNase protection assay; however, the mechanism of DNA packaging into vesicles remains unknown. Although the presence of DNA in EVs was previously controversial, several studies proved the transfer of the genetic material to other microorganisms via vesicles. It is likely that not all EVs carry DNA, and it is still uncertain whether all EVs containing DNA from the parent cells are able to transfer the genetic materials to other cells or even different organisms.

Several proteomic studies have been performed using Gram-negative bacterial OMVs to elucidate the biogenesis and functions of OMVs, as well as to develop diagnostic tools, vaccines, and antibiotics effective against pathogenic bacteria (16). In contrast to the proteomic studies on vesicles, little has been done to characterize the DNA content of EVs. It is not yet known what genes are packaged or whether there is random or preferential gene packaging from parent organisms into EVs to enable them to transfer novel functions to other organisms. Available information on the DNA content in EVs is still too limited to understand their biogenesis and functions in bacterial communities.

In the present study, we report here the production of EVs from a hyperthermophilic archaeon, “T. onnurineus” NA1T (ToEVs), and characterize their physical features and DNA content. Specifically, we conducted extensive DNA sequencing to analyze the genome sequences present in ToEVs, which led to the unexpected discovery that a specific small region of the genome is not represented in the ToEV DNA. We speculate that this finding might be relevant to the mechanism of DNA packaging from parent cell to vesicle and/or to vesicle production.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Isolation of archaeal strains and cultivation of T. onnurineus strain NA1T.

Sediment samples were collected from the PACMANUS hyperthermal field (3°44′S, 151°40′E) at a depth of 1,650 m in the Manus Basin and from the caldera region (31°39.749′N, 130°46.290′E) at a depth of about 200 m in Kagoshima Bay, Japan. After inoculation of sediment samples, the enrichment cultures were grown in 25-ml serum vials containing 20 ml of yeast extract-peptone-sulfur (YPS) medium at 80 to 90°C for 3 days under anaerobic conditions (17). Colonies were randomly picked and purified by streaking onto YPS-Phytagel four times successively. Purified isolates were checked microscopically after a serial dilution and designated NA1 and NA2 for samples from Manus Basin and KBA1 for samples from Kagoshima Bay. NA1 was classified as T. onnurineus NA1T (17), and NA2 and KBA1 were tentatively classified as novel species of the genera Pyrococcus and Thermococcus, respectively (see Fig. S1 in the supplemental material).

T. onnurineus NA1T was routinely cultured in a yeast extract-peptone-formate medium under anaerobic conditions at 80°C. The detailed description of this medium was provided in a previous study (18). To concentrate and purify the ToEVs, the strain was cultivated in a modified formate medium 1 (30), including 1.0 g liter−1 yeast extract, 13.6 g liter−1 sodium formate, and 35 g liter−1 NaCl. Trace elements and vitamins were added, and the pH was adjusted to 6.0 to 7.0 (18). All incubations were carried out at 80°C under anaerobic conditions for 8 h unless otherwise stated.

Purification of extracellular vesicles.

After incubation, the culture broth (15 liters) was spun down at 10,000 × g for 30 min at 25°C using a high-speed centrifuge (2236HR; Gyrogen) equipped with a GRF-500-6 rotor to sediment the cells. The supernatant was concentrated about 100-fold using an ultrafiltration system with a 100-kDa cutoff membrane (Millipore) after prefiltration through 0.45- and 0.2-μm-pore-size membrane filters (Advantec). The concentrated samples were once again filtered using a 0.2-μm-pore-size syringe filter, and then the samples were spun down by ultracentrifugation (Himac CS120GXL; Hitachi) at 88,000 × g for 30 min at 4°C. The vesicle pellet at the bottom of the centrifuge tube was resuspended overnight at 4°C in 500 μl of 1× TBT buffer (100 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM NaCl, 10 mM MgCl2 [pH 7.4]) using a slow rotator. The vesicle samples were treated with10 μg ml−1 (each) DNase and RNase A (Sigma) at 25°C overnight, and heat inactivation of the nucleases was performed at 70°C for 10 min. The vesicle samples in 1× TBT buffer supplemented with 35% CsCl (Sigma) were ultracentrifuged at 174,000 × g for 20 h at 4°C using a swing bucket rotor (S52ST-0352; Hitachi). After CsCl-density gradient equilibrium ultracentrifugation, we measured the distance from the bottom of the tube to the surface layer or the EV band layers, and the CsCl gradient solution in the tube was sampled in 0.5-cm layers from the surface layer to the bottom by the side puncture technique, using sterilized 1-ml syringes. At the same time, the EV bands were separately recovered from the lower boundary of each band by the same side-puncture method. The refractive index (RI) value of each sample was determined by using an Abbe refractometer (Atago). To calculate the buoyant density (BD) at 25°C (ρ25), the measured RI values were inserted into the following equation:

| (1) |

A second equation for correlation of the buoyant densities calculated from equation 1 and the distances of each layer measured from the bottom was generated as follows:

| (2) |

where d represents the distance of the middle of an EV band layer from the bottom in cm and R2 represents the coefficient of determination meant for the relative significance of regression.

To remove the CsCl from the recovered EVs, the samples were placed in a sterilized Spectra/Por 4 dialysis membrane (molecular mass cutoff, 12,000 to 14,000 Da; Spectrum Labs) and dialyzed five times against 100 volumes of sterilized 1× TBT buffer at 4°C. The sample of purified EVs was preserved at 4°C for further experiments.

Electron microscopic observation.

To examine the surface of cells for the presence of EVs, cells of the three isolated Thermococcales strains were observed by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) (17). The cells were harvested at the end of the exponential growth phase and fixed overnight at 4°C in 2% (vol/vol) glutaraldehyde in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4). The fixed cells were filtered through a 0.2-μm-pore-size polycarbonate membrane filter and then rinsed in 1× TBT buffer. Samples were sputter coated with gold and then examined by SEM (JSM-840A; JEOL) at a magnification of ×15,000 at 5 kV.

To observe the T. onnurineus NA1T cells by transmission electron microscopy (TEM), the cells were centrifuged at 4,700 × g for 5 min at 20°C after cultivation. The cell pellets were fixed in 0.1 M cacodylate buffer (pH 7.4) containing 2.5% (vol/vol) glutaraldehyde for 2 h and then placed on a carbon-coated Formvar grid (EMS). Negative staining was performed by adding a droplet of 2% (wt/vol) uranyl acetate onto the grid for 10 s and then removing the excess. The grids were rinsed three times with droplets of ultrapure H2O and then observed using TEM (JEM1010; JEOL) operated at 80 kV (19).

Counting and measuring EVs.

(i) TEM.

Purified EVs were fixed overnight at 4°C with 10 mM EDTA containing 2.5% (vol/vol) glutaraldehyde, and then the sample was placed on a carbon-coated Formvar grid (EMS), placed in an ultracentrifugation tube, and spun at 46,000 × g for 90 min at 20°C using an ultracentrifuge (Himac CS120GXL; Hitachi) with an S52ST-0352 rotor (19). Negative staining was performed as described above.

(ii) qNano.

The qNano system (Izon) is a relatively new technology that allows the detection of EVs passing through a nanopore by way of single-molecule electrophoresis (20). The technology is based on the Coulter principle at the nano scale and operates by detecting transient changes in the ionic current generated by the transport of the target particles through a size-tunable nanopore in a polyurethane membrane. EVs were diluted to ∼10−3 with 1×-sterilized TBT buffer in a small sterile tube, and the diluted sample was vigorously shaken for 1 h using a vortex mixer and measured using an NP150 nanopore aperture. When the sample plugged the nanopore, the shaking time was extended after the addition of 7.6 mM EDTA solution to disperse the vesicles. Calibration was performed using CP100 carboxylated polystyrene calibration particles (Izon) as a standard according to the manufacturer's instructions.

(iii) Epifluorescence microscopy.

To count the DNA-containing ToEVs, the sample was stained with SYBR gold nucleic acid gel stain (Invitrogen) and examined at 1,600-fold magnification under a Zeiss epifluorescence microscope (21). The SYBR gold solution was added to 10 μl of ToEV sample (final SYBR gold concentration, 100×). After incubation at room temperature in the dark for 15 min, the sample was filtered through a 0.015-μm-pore-size polycarbonate membrane filter (Whatman International, United Kingdom) with a 0.8-μm-pore-size backing membrane filter. After drying, the filter was mounted on a glass slide, and the ToEVs were counted under green epifluorescent excitation.

Electrophoretic analysis of nucleic acid in ToEVs.

To cleanly remove the vesicle-associated DNA, EVs mixed with or without pUC19 (the ratio of EV DNA to pUC19 DNA was approximately 1:4) were treated with 10 μg of nucleases for 16 h at 37°C. After heat inactivation of the nucleases at 70°C for 10 min, EV DNA was extracted with a vRD kit (Geneall). The extracted DNA was separated in a 1% agarose gel. To estimate the DNA size and also for use in marker PCR and sequencing analysis, EVs were always treated by the same method as described above prior to DNA extraction. To test whether the EV DNA was linear or circular in form, purified DNA was digested with endonucleases such as BamHI, EcoRI, HindIII, NotI, and SacI at 37°C for 2 h, and then the treated and nontreated DNA samples were resolved in parallel by 1% agarose gel electrophoresis.

EV DNA sequencing and reference assembly.

DNA was extracted from collected ToEVs with minimal contaminants (T. onnurineus NA1T itself and any other organisms, as determined by epifluorescence microscopy and TEM) using a vRD kit. EV DNA (ca. 100 ng) was used for library construction according to the manufacturer's instructions (Ion Torrent, San Francisco, CA), which was followed by sequencing using the NGS technique on an Ion Torrent Personal Genome Machine (Life Technologies, San Francisco, CA). We obtained 420.76 Mb (2,578,006 reads; mean read length, 202 bp) of high quality reads (Q20) from an overall total of ∼521.82 Mb of sequence data. Only high-quality reads were used for reference genome assembly on the complete T. onnurineus NA1T genome (NC_011529) using CLC Genomics Workbench v.5.5.1 (CLC Bio, Aarhus, Denmark).

Genome-spanning gene primers and amplification.

To determine the presence of T. onnurineus NA1T genes in ToEVs, 36 paired primers were designed at intervals of ∼50 kb on the basis of the known genomic sequences of T. onnurineus NA1T (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Purified DNAs of ToEVs, and of T. onnurineus NA1T as a reference, were amplified for 35 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 2 min, and the products were separated on a 1% agarose gel.

GenBank accession numbers.

The GenBank/EMBL/DDBJ accession numbers for the 16S rRNA gene sequences of Pyrococcus sp. strain NA2 and Thermococcus sp. strain KBA1 are CP002670 and KP299296, respectively.

RESULTS

Morphological characteristics of ToEVs.

Three Thermococcales strains were cultivated, and the cell surfaces were observed by SEM. Although no bud-like structures, presumptive EVs, were found on Pyrococcus sp. strain NA2, both T. onnurineus NA1T and Thermococcus sp. strain KBA1 had EV-like structures budding from the surfaces of the cells (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Presumptive EVs were more abundant on the cell surfaces of the KBA1 strain than on the NA1 strain.

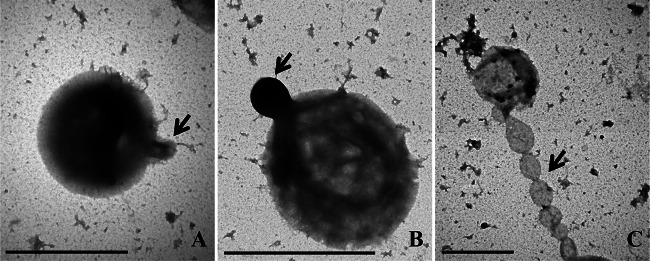

Of the two vesicle-producing Thermococcus strains, T. onnurineus NA1T was chosen for further examination as an EV producer in the present study because the parent microorganism had already been taxonomically identified and studied by genomic and proteomic approaches (17, 22, 23). TEM images of negatively stained cells appeared to show that the vesicles budded from the surfaces of parent cells (Fig. 1A and B). A lumen-like structure within the developing bud protruded from the parent cell (Fig. 1A), and then these buds were pinched from the cell surface (Fig. 1B) and liberated into the surrounding milieu as EVs. During the budding of a vesicle, it is likely that the electron-dense body (EDB) moves from the parent cell to the bud's lumen, as the vesicle continues to grow and finally is released from the parent cell. A unique chain of vesicles connected to a host cell (Fig. 1C) was also observed.

FIG 1.

TEM images of negatively stained T. onnurineus NA1T cells. (A) Vesicle protruding from the parent cell surface, early stage. (B) Vesicle bud almost pinched off from the surface of parent cell, about to be released as an EV. (C) Vesicles connected to the parent cell as a chain. The highly electron-dense cytoplasmic materials appear as a dark color inside the cell and EV. Arrows indicate ToEVs. Scale bar, 1 μm.

To purify the EVs, the culture broth (15 liters) of T. onnurineus NA1T cells was centrifuged to eliminate the parent cells, and then the supernatant was concentrated by a tangential-flow membrane filter system as described in Materials and Methods. The concentrated ToEVs were further purified by CsCl gradient ultracentrifugation. After the separation of vesicles in the CsCl gradient, we found four distinct bands having different buoyant densities, with two major bands having buoyant densities of 1.2434 g cm−3 (band B) and 1.2648 g cm−3 (band C). The two additional bands (A and D) were occasionally seen in large-volume batch cultures (100 to 150 liters) but not both bands at the same time, even when the culture conditions were the same. For example, one lighter vesicle band, band A (ρ25 = 1.1899 g cm−3), was located above band B and a heavier band, D (ρ25 = 1.2828 g cm−3), was located below band C. However, these two bands were not consistently present, and we did not obtain enough of these vesicles for further experiments. Thus, we report here only on the ToEVs of the two major bands, B and C, for which sufficient vesicles were purified.

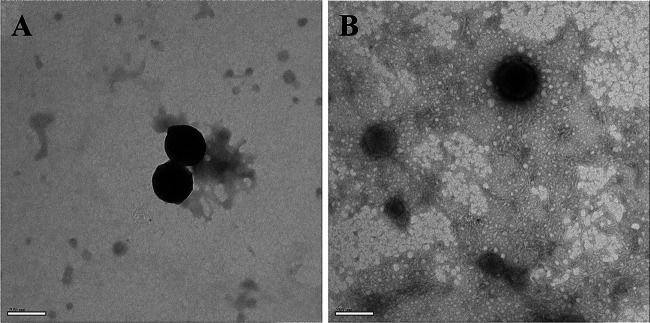

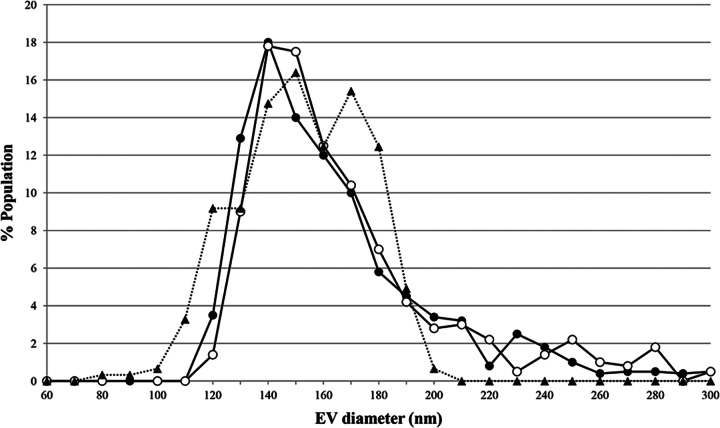

The ToEVs of bands B and C were negatively stained and examined by TEM. There was no morphological difference in the ToEVs from bands B and C. Both ToEVs were spherical in shape without any tail (Fig. 2), and we could not find any typical virus-like structure associated with the ToEVs. According to the number of ToEVs counted from purified bands B and C by qNano, the vesicle production levels were estimated to be 2.7 × 1010 and 3.7 × 1010 liter−1 of culture medium, respectively, and the band B/band C production ratio was about 2:3. The size and number of ToEVs in the subsamples were counted and measured by two methods, TEM and qNano. The sizes were determined to be in the range of 80 to 210 nm and 120 to 550 nm by TEM and qNano, respectively (Fig. 3). Although the size range of EVs measured by qNano seems to be slightly greater than that determined by TEM, no significant difference between the two measurements was detected by Student t test (P > 0.05). The size distribution of ToEVs in band B was identical to that of ToEVs in band C, as confirmed by qNano. The mode value for vesicles from both bands was 140 nm.

FIG 2.

TEM images of negatively stained ToEVs in band B (A) and ToEVs in band C (B). ToEVs were suspended in TBT buffer, adsorbed to a carbon-coated grid, and negatively stained for 30 s with 2% uranyl acetate. Scale bars, 100 nm.

FIG 3.

Size distribution of ToEVs estimated by qNano and TEM. ●, qNano/ToEVs of band B; ○, qNano/ToEVs of band C; ▲, TEM/ToEVs of band C. The figure depicts the diameter of vesicles (in nm) versus normalized counts of vesicles (%). The size distribution of ToEVs bigger than 300 nm is not presented.

Advantages of qNano are that it is time saving and less laborious to count the number of vesicles and to measure the size for comparison with TEM images. However, when vesicles aggregated into clumps, qNano likely recognized these as single vesicles, giving an incorrect size and number. qNano showed the size of several vesicles to be bigger than 200 nm, which was not found from the TEM observations on samples purified using a 0.2-μm-pore-size membrane filter (Fig. 3). In the size distribution profile from the qNano analysis, we found two or three peaks in the distribution curve that were larger than 200 nm, which likely were aggregates of two, three, or even more vesicles. Therefore, the number of vesicles in the present study was counted using only those with a diameter smaller than 210 nm. The qNano counts of ToEVs would obviously be underestimates if the vesicle aggregation in the sample was serious. This drawback could be minimized by disaggregating vesicle samples by vigorous shaking. Furthermore, treatment of the vesicle sample with a nonionic detergent could also enhance disaggregation.

According to the manufacturer's information, the NP150 nanopore used in this experiment should be able to count the particles efficiently in the range between 75 and 300 nm. However, vesicles smaller than 120 nm could not be confirmed by qNano, whereas TEM analysis showed such vesicles to be ca. 5% of the total, when the vesicles were not shrunk by the preparation procedure for the TEM sample. It is possible that qNano might underestimate the total count of ToEVs ca. 5% due to a detection limit for particles smaller than 100 nm. This drawback of the qNano method was also pointed out by Momen-Heravi et al. (20).

The numbers of nucleic acid-containing ToEVs of bands B and C were counted by epifluorescence microscopy with the SYBR gold staining method. The ratios of the number of SYBR gold-stained vesicles to the total number of vesicles counted by qNano were ca. 58% ± 6% and 81% ± 4% (n = 3), respectively, for bands B and C.

Biochemical characteristics of ToEVs.

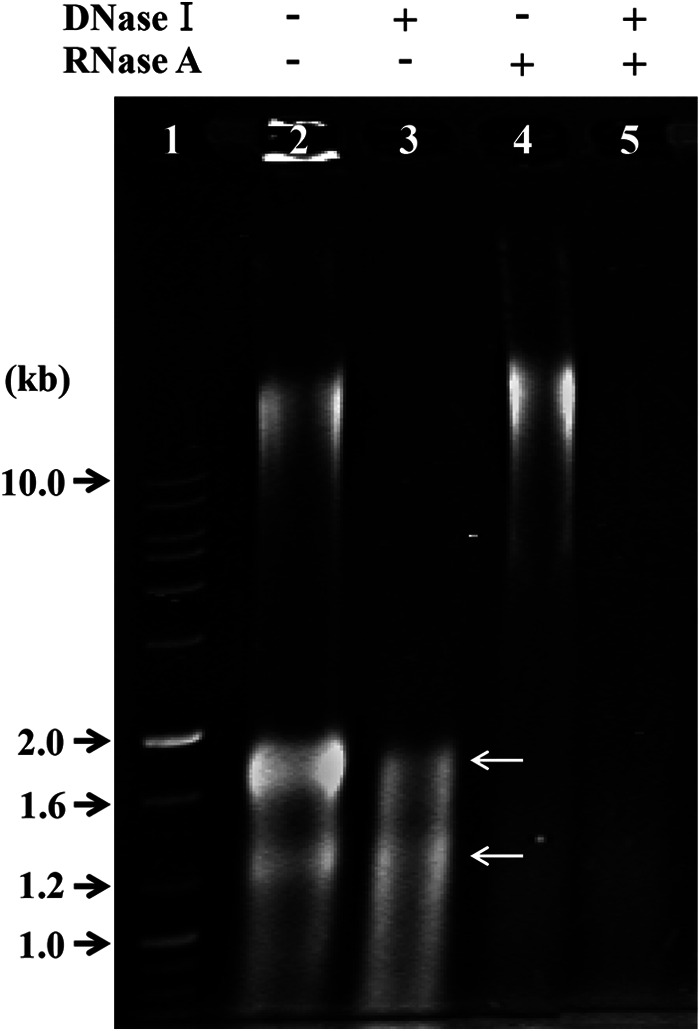

To test whether ToEVs contain DNA or not, nucleic acids were extracted from ToEVs of band C. The electrophoretic analysis of nucleic acids from ToEVs was performed after treatment with a combination of DNase and RNase (Fig. 4). The sample of nucleic acids purified from ToEVs without any DNase and RNase showed DNA and RNA bands (lane 2); however, no band was found when it was treated with both enzymes (lane 5). When this sample was pretreated with DNase (lane 3) and RNase (lane 4), the DNA and RNA bands, respectively, disappeared. These results strongly support the view that ToEVs carry DNA and RNA.

FIG 4.

Electrophoretic analysis of ToEV nucleic acids without or with DNase and RNase treatment. Lane 1, 1-kb DNA ladder; lane 2, no treatment with DNase and RNase; lanes 3 and 5, nucleic acids of ToEVs treated with DNase I; lanes 4 and 5, nucleic acids of ToEVs treated with RNase A. White arrows indicate two rRNAs in lanes 2 and 3.

The DNA isolated from the vesicles could either be originating from inside bona fide vesicles or be from contaminated surfaces and/or free DNA from the surroundings. To confirm the origin of DNA associated with the EVs, purified ToEVs with or without added pUC19 DNA were treated with DNase I. Total DNA extracted from ToEVs plus pUC19 DNA without DNase I showed three distinctive bands (see Fig. S3, lane 3, in the supplemental material); however, only one band (near 10 kb) remained after DNase I treatment (see Fig. S3, lanes 2 and 4, in the supplemental material).

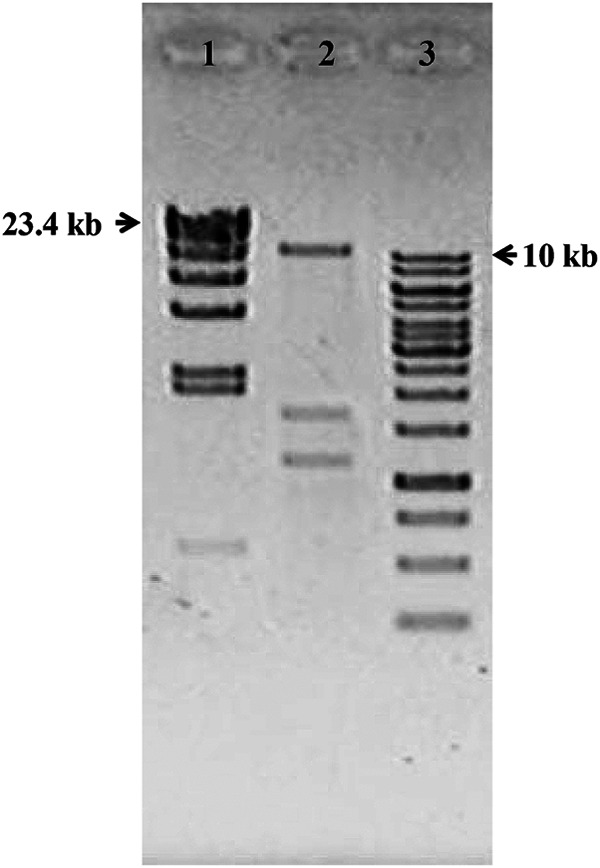

To estimate the size of the DNA in the vesicles, the ToEV DNA, which was apparently packaged from the T. onnurineus NA1T genome into the EVs, was extracted, purified, and then separated in a 1% agarose gel (Fig. 5). The mobility of the ToEV DNA band treated by endonucleases prior to the gel electrophoresis did not show any difference compared to the untreated DNA. This indicates that the ToEV DNA is linear in form. Based on the finding that ToEV has linear double-stranded DNA, the size of the DNA was estimated to be ∼14 kb from the relationship between molecular weight and the distance of DNA band migration. The DNA packaged into ToEVs was <1/100 the size of the genome of the parent microorganism (1,848 kb).

FIG 5.

Size estimation of DNA from ToEVs. Lane 1, lambda/HindIII DNA ladder; lane 2, total nucleic acids isolated from ToEVs; lane 3, 1-kb DNA ladder. Molecular sizes are indicated in kilobases. The lower two discrete bands in lane 2 represent RNA bands as shown in Fig. 4.

To confirm that the purified ToEVs were produced by the T. onnurineus NA1T cells, 16S rRNA genes extracted from ToEVs were amplified with primer TON_1979 coding for 16S rRNA and sequenced. The EVs contained the same 16S rRNA gene sequence as the parent archaeon. This confirms observations that vesicles were produced by the parent archaeal cell. It appears that DNA is packaged into the lumen of the protruding bud before the vesicles are freed from the parent cell. To determine whether any region of the genome is preferentially packaged from the parent cells into ToEVs, the extracted ToEV DNA was amplified using paired primers for 36 protein-encoding genes that were selected so as to span the T. onnurineus NA1T genome at regular intervals (see Table S1 in the supplemental material). Of the 36 parent markers, 35 markers (only TON_0544 was an exception) were represented in the DNA from the EVs of bands C (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material) and B, while the DNA of the parent cells that produced the vesicles showed the presence of all the markers, including TON_0544.

Analysis of the ToEV DNA.

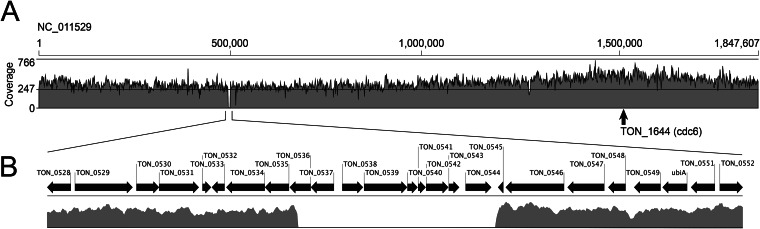

To determine whether only open reading frame (ORF) TON_0544 was missing from the collective “genome” of ToEVs or whether any other gene was also excluded during the DNA packaging process from the parent cells to EVs, the entire DNA complement encapsulated in the vesicles (band C) was sequenced. These ToEV DNA sequence reads (total of 2.58 million reads) were assembled on the reference genome of T. onnurineus NA1T, for a total of 1,847,607 bp (NC_011529 [22]). From the assembled ToEV DNA sequence, all gene sequences in the vesicles were derived from the parent cell. There were no other archaeal, prokaryotic, eukaryotic, or inserted viral sequences. Mapping of reads on the reference genome revealed that 99.5% of the T. onnurineus NA1T genome was covered with a 246.8× mean coverage (standard deviation, 56.4×; maximum, 766×), and 0.5% of the genome was not covered by any reads (Fig. 6). From the distribution of ToEV DNA sequences on the genome map of T. onnurineus NA1T, there was a reproducible overabundance of reads from the region of the predicted chromosomal replication origin (oriC locates at TON_1644 [24]) (Fig. 6A). The 0.5% uncovered part of the genome existed as a single region of ∼9,400 bp (TON_0536 to TON_0544 of NC_011529). ORFs from TON_0536 (875 bp) to TON_0544 (1,221 bp) were assigned as hydrogenase (gamma subunit), sulfhydrogenase (beta subunit), hypothetical formate transporter, hypothetical formate dehydrogenase (alpha subunit), oxidoreductase iron-sulfur protein, 4Fe-4S cluster-binding protein, glutamate synthase (beta chain-related oxidoreductase), 4Fe-4S cluster-binding protein, and alcohol dehydrogenase, respectively. Furthermore, the 3′ region of TON_0536 (258 bp) was found in the ToEV DNA sequences, but the 5′ region was not (617 bp).

FIG 6.

(A) Coverage of T. onnurineus NA1T genome by DNA sequencing reads for ToEVs. The mean coverage was about 247×, with a 56.4× standard deviation and a maximum coverage of 766×. An arrow indicates the predicted chromosomal replication origin (oriC) of T. onnurineus NA1 at the specific genomic position of 1,508,116 bp. (B) Expanded unrecovered region (∼9.4 kb) of the T. onnurineus NA1T genome. No reads for ToEVs were obtained for ORFs of the T. onnurineus NA1T genome from TON_0536 to TON_0544.

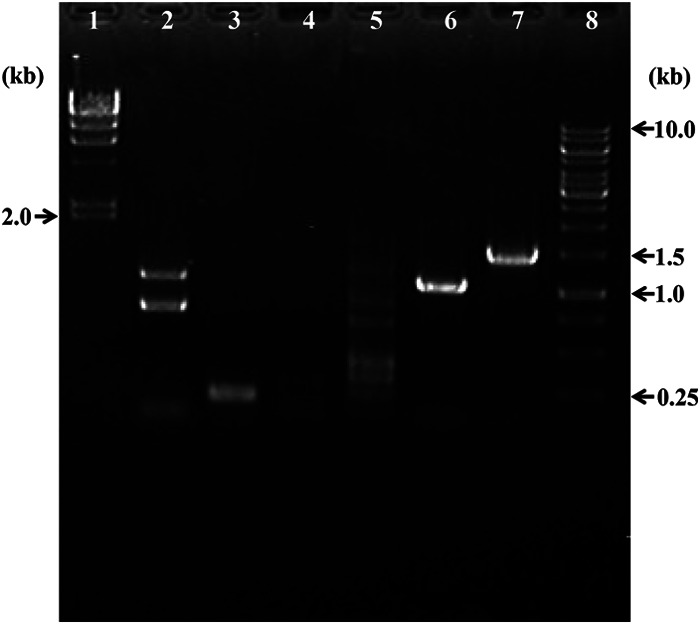

A question was raised whether the same region (∼9.4 kb) of the T. onnurineus NA1T genome was repeatedly missing in the ToEVs purified from different batch cultures. If only occasionally a certain part of the genome fails to get packaged into ToEVs, it is possible that the excluded region could be recovered from another batch of EVs. DNA was extracted from ToEVs that were purified from the broth of another batch culture of T. onnurineus NA1T. It was amplified using primers for TON_0494, the TON_0536 3′ region (forward, 5′-CGGCGTTGATACTATGTC-3′; reverse, 5′-GATGTATAAGGCGGTCTTC-3′, size 200 bp), TON_0598, and TON_1979, which existed in the previous ToEV DNA, and primers for the TON_0536 5′ region (forward, 5′-GAGATCCTTCATGGCTTC-3′; reverse, 5′-CATGTGTCACGACAATCC-3′, size 500 bp) and TON_0544, which were not present.

The absence of a specific region of the genome in the vesicles was confirmed by PCR using the ToEV DNA of band C purified from the independent batch culture (Fig. 7). We confirmed the sequence of the PCR product of TON_0544 against the genomic DNA of the parent cell that had produced the vesicles in the same batch culture and the nonspecific PCR products of TON_0544 (lane 5) against ToEV DNA. These results clearly indicated that the 5′ region of TON_0536, as well as TON_0544, of the T. onnurineus NA1T genome had not been packaged into the ToEVs, whereas TON_0494, the 3′-region of TON_0536, TON_0598, and TON_1979 gave the same result seen previously. ToEV DNA from band B was also examined using these specific primer sets, and the result was the same as for DNA from ToEV band C (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material).

FIG 7.

Gel electrophoresis for PCR products of ToEVs amplified by specific primers. Lane 1, lambda/HindIII DNA ladder; lane 2, TON_0494; lane 3, 3′ region of TON_0536; lane 4, 5′ region of TON_0536; lane 5, TON_0544; lane 6, TON_0598; lane 7, TON_1979 (16S rRNA genes); lane 8, 1-kb DNA ladder. The molecular sizes are indicated.

DISCUSSION

The presence of vesicles in cultures of various thermophilic archaea has been described previously, but only superficially (25, 26). According to an extensive electron microscopy study of vesicles produced from hyperthermophilic archaea of the order Thermococcales, most isolated strains, 26 of 34, produced various types of spherical vesicles (6). In the present study, we confirmed that two of three Thermococcales isolates were able to produce vesicles (see Fig. S2 in the supplemental material). Based on this result and the report of Soler et al. (6), the production of vesicles is a widely distributed feature in hyperthermophilic Thermococcales and could involve a conserved mechanism for their production.

The morphological features of such vesicles are similar regardless of the parent microorganism (archaea, bacteria, or eukaryotes) producing them (1). The ToEVs were spherical, without a tail (Fig. 1 and 2), and they had the same vesicle morphology as those previously reported from other microorganisms, except for their size. It is well established that Gram-negative bacterial MVs range from 10 to 300 nm in diameter and that MVs derived from Gram-positive bacteria, such as Bacillus spp., are between 50 and 150 nm in diameter (1). Archaeal MVs, such as those released by Sulfolobus species, range from 90 to 230 nm in diameter. Eukaryotic microbial vesicles, derived from fungi and parasites, include at least two vesicle populations, exosomes and shedding MVs, which range from 40 to 100 nm and 100 to 1,000 nm in diameter, respectively (1). ToEVs in the present study ranged between 80 and 210 nm, as determined by TEM. These EVs were clearly different from the morphology of a phage or virus which possesses a head, tail, tail fibers, or a structurally unique capsid. The vesicles are likely produced by a budding process analogous to that seen in yeast and different from the mechanism of virus production. The ToEVs did not show a double-bilayer structure such as reported for the OMVs of the psychrotolerant, Gram-negative bacterium, Shewanella vesiculosa M7T (27). Archaeal cells have a different cell membrane and wall architecture than Gram-negative bacteria. The Thermococcus cell wall consists of a single plasma membrane and an outer protein matrix called the S layer, without a periplasmic space, and thus cannot form a bilayered structure. ToEVs were surrounded by a thick, somewhat electron-transparent layer, likely the S layer, and an electron-dense single-layer plasma membrane, which is not easily distinguished from the darkly staining cytoplasmic contents inside the ToEVs (Fig. 2). Similar to the chain of vesicles that was observed in the present study (Fig. 1C), there are several reports on unique forms of vesicles, such as tube shaped, branched, chain of pearls, and so on (6). Interestingly, no EDB was observed in this chain of vesicles, while the parent cell showed a “beads on a string” EDB that resembled a nucleosome-like structure.

It has been argued that most vesicles of Thermococcales strains do not contain bona fide intravesicular DNA, but rather that the DNA is strongly bound to vesicles or trapped in vesicle clusters (6). In the present study, we confirmed that the purified ToEVs were free of any DNA except for DNA in the lumens of the EVs (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material). Consistent with this, the stability of DNA in the lumens of EVs against heat and nucleases indicates that DNA within EVs is protected from hostile conditions, which would increase the efficiency of a putative vesicle-mediated DNA delivery to a recipient cell.

The ToEV DNA averaged ∼14 kb in size (Fig. 5), sufficient to encode multiple proteins. For comparison, vesicles of T. nautilus 30-1 harbored the endogenous plasmid pTN1, which was derived from the host archaeal cells, and was ∼3.4 kb in size (14), whereas DNA ∼310 kb in size was reported from the vesicles of T. kodakarensis B41 (8). The DNA size of the ToEVs was within the size range of DNA found in vesicles produced by two hyperthermophilic archaea, T. nautilus and T. kodakarensis. The sizes of DNAs in vesicles from the bacteria Prochlorococcus (13) and Aquifex sp. (5) have been reported to be about 3 and 406 kb, respectively. The vesicle DNA fragments from the cyanobacterium Prochlorococcus MED4 were heterogeneous in size, with some measuring at least 3 kb (13). It is obvious that the DNA size in vesicles showed a wide range depending on the parent organism producing the vesicles. Although smaller than the exceptionally large molecules of T. kodakarensis and Aquifex sp., ToEVs contained genomic DNA of sufficient size for gene transfer, because DNA exceeding 1 kb in length can be utilized as an information molecule when it is transformed into recipient cells (28, 29).

Even though the presence of DNA in vesicles has been reported frequently, information about the genome sequences found in vesicles has remained surprisingly scarce. As far as we know, there have been only two reports of sequence data for DNA retrieved from vesicles; a Gram-negative alphaproteobacterium, Ahrensia kielensis B9; a gammaproteobacterium, Pseudoalteromonas marina mano4; and a cyanobacterium, Prochlorococcus MED4 (12, 13). Since both of these studies amplified the vesicle DNA to construct libraries, an artifact could not be entirely ruled out. In the present study, we sequenced DNA from about 1.7 × 1011 ToEVs from archaeal vesicles without amplification. Hagemann et al. (12) obtained about 30 and 46 kb of sequence information from vesicle genome libraries of A. kielensis and P. marina, respectively. All sequences were prokaryotic except for one sequence showing significant similarity with a eukaryotic gene. Biller et al. (13) found that vesicle DNA corresponded to broadly distributed regions of the MED4 genome, representing >50% of the entire chromosomal sequence. The sequence data obtained for ToEV DNA indicated that all sequences were derived from the parent cell DNA. We found almost all regions of the T. onnurineus NA1T genome (the whole genome is about 1.85 Mb), representing >99.5% of the entire chromosomal sequence (Fig. 6) in EV DNA. Our results suggest that the frequency of packaging specific DNA sequences into ToEVs has a possible link to the chromosomal replication step, since we noted an overabundance of reads from a region of T. onnurineus NA1T encoding the chromosomal replication origin (oriC), as indicated by an arrow in Fig. 6A. No information exists on whether the DNA fragment formation for packaging is a random or organized process. From our results, we can speculate either that DNA fragments from near the origin are more abundant in the cell or that the DNA fragments averaging about 14 kb start to fragment from the replication origin, and therefore those fragments are preferentially packaged from the parent cells to vesicles. However, this result is the exact opposite of the finding of an overabundance for vesicle DNA sequences at the predicted chromosome terminus location of Prochlorococcus MED4 (13). This opposite result might be an artifact due to extensive amplification of vesicle DNA. It might also reflect differences in the parent organisms, archaea and bacteria.

The absence of 0.5% of the parent genomic sequence between TON_0536 and TON_0544 in the ToEVs is not an artifact. The absence of this region was confirmed by the PCR result for TON_0544 from the vesicle DNAs of bands B and C even when the vesicles were isolated from two different batch cultures (see Fig. S4 and S5 in the supplemental material; Fig. 7). Furthermore, the 5′ region of TON_0536 (617 bp) was repeatedly missing from the vesicle DNA purified from a different batch culture, while the 3′ region (258 bp) was present in the DNA analysis, suggesting the 5′ region was very specifically not delivered into the vesicle (see Fig. S5 in the supplemental material; Fig. 7). There are a number of possible explanations for how this region of the genome was missing from the DNA of vesicles. One possibility might be that this region of the genome was not present in the genome of the parent cells due to a genetic instability of the microorganism. However, we confirmed that the missing DNA fragment was present in the genome of the parent cell (see Fig. S4 and S5 in the supplemental material). A second possibility is that this region of the genome could not be replicated and fragmented because it was directly bound to a protein that fulfills an important function such as the fragmentation of DNA or packaging of DNA fragments into vesicles, and therefore it was not physically moved into the vesicle lumen.

On the basis of our results, we hypothesize that the unpackaged part of the T. onnurineus NA1T genome plays an indispensable role in the process for DNA delivery into ToEVs and/or the mechanism of ToEV production. We are now constructing T. onnurineus NA1T mutants lacking the unpackaged genomic region and will investigate the effect of such mutations on ToEV production and ToEV DNA composition in the near future.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank E. S. Choi for the EV counting by TEM and J. P. van der Meer for English correction.

This study was supported by the KIOST in-house programs (PE99314, PE99252, and PE99263), as well as the Marine and Extreme Genome Research Center Program and the Development of Biohydrogen Production Technology Program of the Ministry of Ocean and Fisheries, Republic of Korea.

Footnotes

Supplemental material for this article may be found at http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/AEM.00428-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Deatherage BL, Cookson BT. 2012. Membrane vesicle release in bacteria, eukaryotes, and archaea: a conserved yet underappreciated aspect of microbial life. Infect Immun 80:1948–1957. doi: 10.1128/IAI.06014-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Prangishvili D, Holz I, Stieger E, Nichell S, Kristjansson JK, Zillig W. 2000. Sulfolobicins, specific proteinaceous toxins produced by strains of the extremely thermophilic archaeal genus Sulfolobus. J Bacteriol 182:2985–2988. doi: 10.1128/JB.182.10.2985-2988.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ellen AF, Albers SV, Huibers W, Pitcher A, Hobel CF, Schwarz H, Folea M, Schouten SM, Boekema EJ, Poolman B, Driessen AJ. 2009. Proteomic analysis of secreted membrane vesicles of archaeal Sulfolobus species reveals the presence of endosome sorting complex components. Extremophiles 13:67–79. doi: 10.1007/s00792-008-0199-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rachel R, Wyschkony I, Riehl S, Huber H. 2002. The ultrastructure of Ignicoccus: evidence for a novel outer membrane and for intracellular vesicle budding in an archaeon. Archaea 1:9–18. doi: 10.1155/2002/307480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chiura HX. 2004. Novel broad-host range gene transfer particles in nature. Microbes Environ 19:249–264. doi: 10.1264/jsme2.19.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Soler N, Marguet E, Verbavatz J-M, Forterre P. 2008. Virus-like vesicles and extracellular DNA produced by hyperthermophilic archaea of the order Thermococcales. Res Microbiol 159:390–399. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2008.04.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chatterjee SN, Chaudhuri K. 2012. Outer membrane vesicles of bacteria. Springer, Heidelberg, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sugitate T, Chiura HX. 2005. Functional gene transfer toward a broad range of recipients with the aid of vector particles originating from thermophiles, p 141–147. In Proceedings of the International Symposium on Extremophiles and Their Applications International Society for Extremophiles, Hamburg, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kulp A, Kuehn MJ. 2010. Biological functions and biogenesis of secreted bacterial outer membrane vesicles. Annu Rev Microbiol 64:163–184. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.091208.073413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manning AJ, Kuehn MJ. 2013. Functional advantages conferred by extracellular prokaryotic membrane vesicles. J Mol Microbiol Biotechnol 23:131–141. doi: 10.4014/jmb.1208.08083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Renelli M, Matias V, Lo RY, Beveridge TJ. 2004. DNA-containing membrane vesicles of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1 and their genetic transformation potential. Microbiology 150:2161–2169. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26841-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hagemann S, Stöger L, Kappelmann M, Hassl I, Ellinger A, Velimirov B. 2013. DNA-bearing membrane vesicles produced by Ahrensia kielensis and Pseudoalteromonas marina. J Basic Microbiol 53:1–11. doi: 10.1002/jobm.201100335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biller SJ, Schubotz F, Roggensack SE, Thompson AW, Summons RE, Chisholm SW. 2014. Bacterial vesicles in marine ecosystems. Science 343:183–186. doi: 10.1126/science.1243457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soler N, Gaudin M, Marguet E, Forterre P. 2011. Plasmids, viruses and virus-like membrane vesicles from Thermococcales. Biochem Soc Trans 39:36–44. doi: 10.1042/BST0390036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaudin M, Gauliard E, Le Normand P, Marguet E, Forterre P. 2013. Hyperthermophilic archaea produce membrane vesicles that can transfer DNA. Environ Microbiol Rep 5:109–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2012.00348.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwon SO, Gho YS, Lee JC, Kim SI. 2009. Proteome analysis of outer membrane vesicles from a clinical Acinetobacter baumannii isolate. FEMS Microbiol Lett 297:150–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01669.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bae SS, Kim YJ, Yang SH, Lim JK, Jeon JH, Lee HS, Kang SG, Kim SJ, Lee JH. 2006. Thermococcus onnurineus sp. nov., a hyperthermophilic archaeon isolated from a deep-sea hydrothermal vent area at the PACMANUS field. J Microbiol Biotechnol 16:1826–1831. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim MS, Bae SS, Kim YJ, Kim TW, Lim JK, Lee SH, Choi AR, Jeon JH, Lee JH, Lee HS, Kang SG. 2013. CO-dependent H2 production by genetically engineered Thermococcus onnurineus NA1. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:2048–2053. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03298-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Børsheim KY, Bratbak G, Heldal M. 1990. Enumeration and biomass estimation of planktonic bacteria and viruses by transmission electron microscopy. Appl Environ Microbiol 56:352–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Momen-Heravi F, Balaj L, Alian S, Tigges J, Toxavidis V, Ericsson M, Distel RJ, Ivanov AR, Skog J, Kuo WP. 2012. Alternative methods for characterization of extracellular vesicles. Front Physiol 3:354. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2012.00354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patel A, Noble RT, Steele JA, Schwalbach MS, Hewson I, Fuhrman JA. 2007. Virus and prokaryote enumeration from planktonic aquatic environments by epifluorescence microscopy with SYBR Green I. Nat Protoc 2:269–276. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee HS, Kang SG, Bae SS, Lim JK, Cho Y, Kim YJ, Jeon JH, Cha SS, Kwon KK, Kim HT, Park CJ, Lee HW, Kim SI, Chun J, Colwell RR, Kim SJ, Lee JH. 2008. The complete genome sequence of Thermococcus onnurienus NA1 reveals a mixed heterotrophic and carboxydotrophic metabolism. J Bacteriol 190:7491–7499. doi: 10.1128/JB.00746-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yun S-H, Kwon SO, Park GW, Kim JY, Kang SG, Lee J-H, Chung Y-H, Kim S, Choi J-S, Kim SI. 2011. Proteome analysis of Thermococcus onnurineus NA1 reveals the expression of hydrogen gene cluster under carboxydotrophic growth. J Proteomics 74:1926–1933. doi: 10.1016/j.jprot.2011.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cortez D, Quevillon-Cheruel S, Gribaldo S, Descoues N, Sezonov G, Forterre P, Serre MC. 2010. Evidence for a Xer/dif system for chromosome resolution in archaea. PLoS Genet 6:e1001166. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Prangishvili D, Forterre P, Garrett RA. 2006. Viruses of the Archaea: a unifying view. Nat Rev Microbiol 4:837–848. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reysenbach AL, Liu Y, Banta AB, Beveridge TJ, Kirshtein JD, Schouten S, Tivey MK, Von Damm KL, Voytek MA. 2006. A ubiquitous thermoacidophilic archaeon from deep-sea hydrothermal vents. Nature 442:444–447. doi: 10.1038/nature04921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perez-Cruz C, Carrion O, Delgado L, Martinez G, Lopez-Iglesias C, Mercadea E. 2013. New type of outer membrane vesicle produced by the Gram-negative bacterium Shewanella vesiculosa M7T: implications for DNA content. Appl Environ Microbiol 79:1874–1881. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03657-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Levine SM, Lin EA, Emara W, Kang J, DiBenedetto M, Ando T, Falush D, Blaser MJ. 2007. Plastic cells and populations: DNA substrate characteristics in Helicobacter pylori transformation define a flexible but conservative system for genomic variation. FASEB J 21:3458–3467. doi: 10.1096/fj.07-8501com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Morrison DA, Guild WR. 1972. Activity of deoxyribonucleic acid fragments of defined size in Bacillus subtilis transformation. J Bacteriol 112:220–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim YJ, Lee HS, Kim ES, Bae SS, Lim JK, Matsumi R, Lebedinsky AV, Sokolova TG, Kozhevnikova DA, Cha SS, Kim SJ, Kwon KK, Imanaka T, Atomi H, Bonch-Osmolovskaya EA, Lee JH, Kang SG. 2010. Formate-driven growth coupled with H2 production. Nature 467:352–355. doi: 10.1038/nature09375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.