Abstract

Background/Aims

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is an important comorbidity after liver transplantation (LT); however, reliable tools with which to evaluate these patients are limited. In this work, we examine the extent to which the addition of serum cystatin C improves GFR estimation and mortality prediction, in comparison to various GFR-estimating equations.

Methods

GFR was measured in LT recipients by iothalamate clearance. Concurrent serum cystatin C was assayed in banked serum samples. Performance of GFR-estimating equations with and without cystatin-C, including the MDRD (Modification of Diet in Renal Disease) and CKD-EPI (Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration) formulas was assessed. The proportional hazards regression analysis was performed to determine the association between serum cystatin-C and mortality.

Results

A total of 586 iothalamate results were obtained in 401 patients after a mean of 4 years post-LT. When compared to measured GFR, the formula with both creatinine and cystatin-C, namely CKD-EPIcr-cys, outperformed those with either marker alone. Performance of creatinine-based models was similar to one another. Serum cystatin-C, by itself or as a part of eGFR was a significant predictor of mortality.

Conclusion

Serum cystatin-C has an important role in enhancing accuracy of GFR estimation and predicting mortality in LT recipients.

Keywords: chronic kidney disease, biomarkers, renal failure

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) is a common complication after liver transplantation (LT) – as many as one fifth of LT recipients may develop chronic renal failure at 5 years post-LT (1). The renal impairment is most commonly attributed to calcineurin inhibitor toxicity, although hypertensive and diabetic nephropathies, glomerular diseases and IgA nephropathy may also play a role in its pathogenesis (2). CKD is clinically significant because it is common and is associated with increased risk of death after LT (3, 4).

Although glomerular filtration rate (GFR) is essential in detection, evaluation and management of post-LT CKD, the optimal means to determine GFR in LT recipients remains to be determined. The gold standard, namely measured GFR by clearance of exogenous markers is impractical for most routine patient care. Estimation of measured GFR from serum creatinine concentration is commonly used and is advocated in most patient populations (5). In LT recipients, the accuracy of serum creatinine-based GFR-estimating equations remains ill-defined (6, 7).

Cystatin C is a small protein that has been characterized as a biomarker for GFR in patients with CKD. Serum cystatin C is less influenced by age, gender, race, muscle mass or diet than serum creatinine, which may make it a more accurate marker for GFR estimation in LT patients(8). In addition to reflecting GFR, serum cystatin-C has been suggested to be an independent predictor of mortality (9) (10).

Recent studies showed that in non-transplant settings, including patients with cirrhosis (11–13), incorporating both cystatin C and creatinine into GFR estimating equations provides the most accurate estimates of GFR compared to either marker alone (14, 15). Consequently, the use of cystatin C-based estimated GFR in certain clinical settings has been suggested by the 2012 Kidney Disease Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) guidelines (5). However, the applicability of these equations in liver transplant recipients remains to be determined. In patients with advanced liver disease, serum creatinine tends to be lower due to sarcopenia and malnutrition, thus creatinine-based equations may overestimate GFR (16, 17). On the other hand, cystatin C levels are higher posttransplant than in the general population; hence cystatin C-based equations may underestimate GFR (18). It remains to be determined if equations combining both markers improve the performance of renal function estimation. Previous studies of serum cystatin C-based estimated GFR in LT recipients have been limited by small sample sizes, non-standardized cystatin C assays, and lack of evaluation of the 2012 CKD-EPI cystatin C equations, advocated in the 2012 KDIGO guidelines (19–21). Finally, it remains to be determined whether a GFR estimating equation specifically developed in LT recipients would be more accurate than other generic equations.

The aims of this study are to i) assess the extent to which the addition of serum cystatin-C improves the accuracy of GFR estimation; ii) examine whether eGFR equations derived in this patient sample may outperform existing eGFR models; and iii) evaluate serum cystatin-C as a predictor of mortality, by taking advantage of measured GFR and standardized cystatin-C data available to us in a large sample of LT recipients.

RESULTS

A total of 586 iothalamate results were available in 401 LT patients who met the study criteria for inclusion in the analysis (Table 1). The mean time interval from LT to these measurements was four years. The median measured GFR (mGFR) was 49 ml/min/1.73m2; approximately 68% of mGFR values were below 60 ml/minute/1.73 m2, indicating chronic kidney disease. The median (interquartile range, IQR) serum concentrations of creatinine and cystatin C were 1.3 (1.1–1.7) mg/dL and 1.7 (1.4–2.3) mg/L respectively.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of subjects

| Characteristic | Subjects N=401 |

|---|---|

| Age- years (range) | 56 ± 11 (19–77) |

| Male sex- no. (%) | 229 (57%) |

| White- no. (%) | 364 (91%) |

| Time since transplant (years) | 4.0 ± 3.6 (0.04–22) |

| Serum creatinine –mg/dL (median, IQR) | 1.3 (1.1–1.7) |

| Serum albumin –mg/dL (median, IQR) | 4.2 (3.9–4.4) |

| BUN – mg/dL (median, IQR) | 26 (18–36) |

| Serum cystatin C – mg/liter (median, IQR) | 1.7 (1.4–2.3) |

| Measured GFR – ml/min/1.73 m2 (median, IQR) | 49 (34–65) |

| Measured GFR – no. (%) | |

| <15 ml/min/1.73 m2 | 16 (2.7%) |

| 15–29 ml/min/1.73 m2 | 86 (14.7%) |

| 30–59 ml/min/1.73 m2 | 294 (50.2%) |

| 60–89 ml/min/1.73 m2 | 149 (25.4%) |

| 90–120 ml/min/1.73 m2 | 40 (6.8%) |

| >120 ml/min/1.73 m2 | 1 (0.2%) |

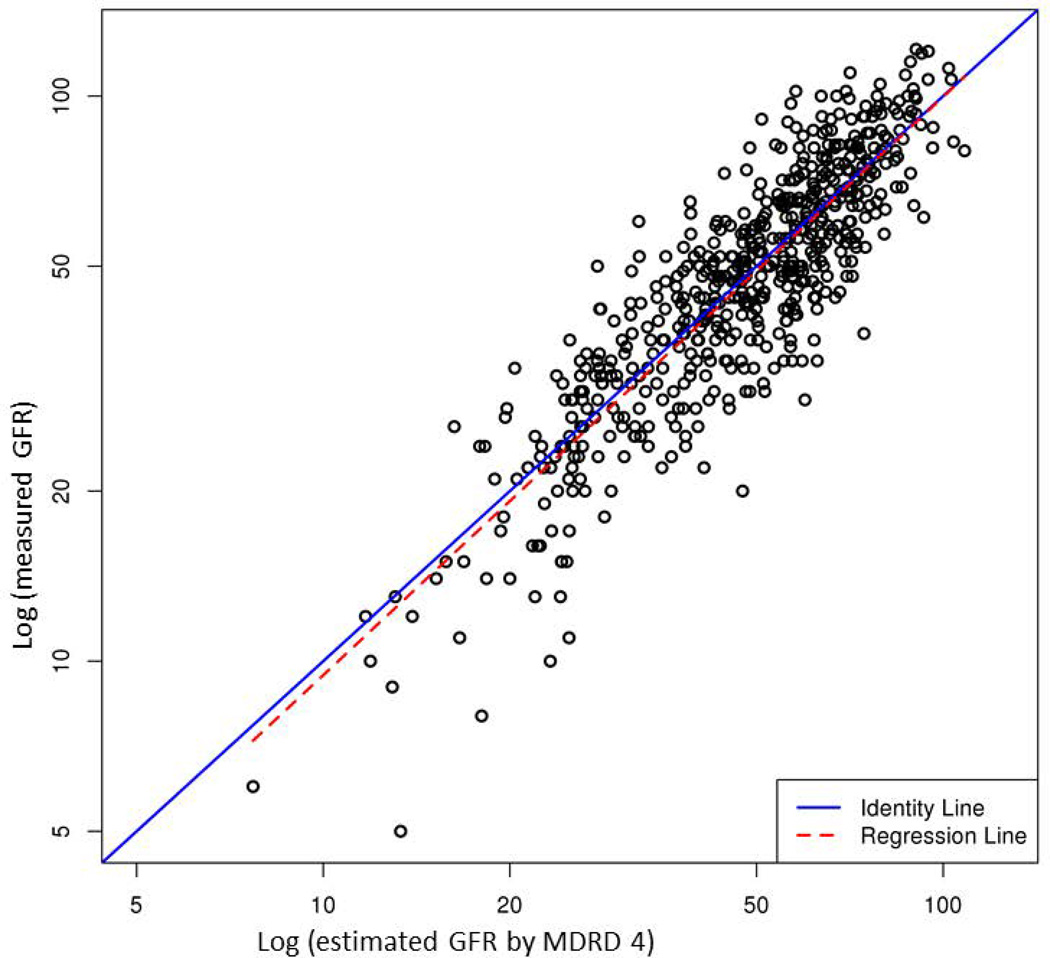

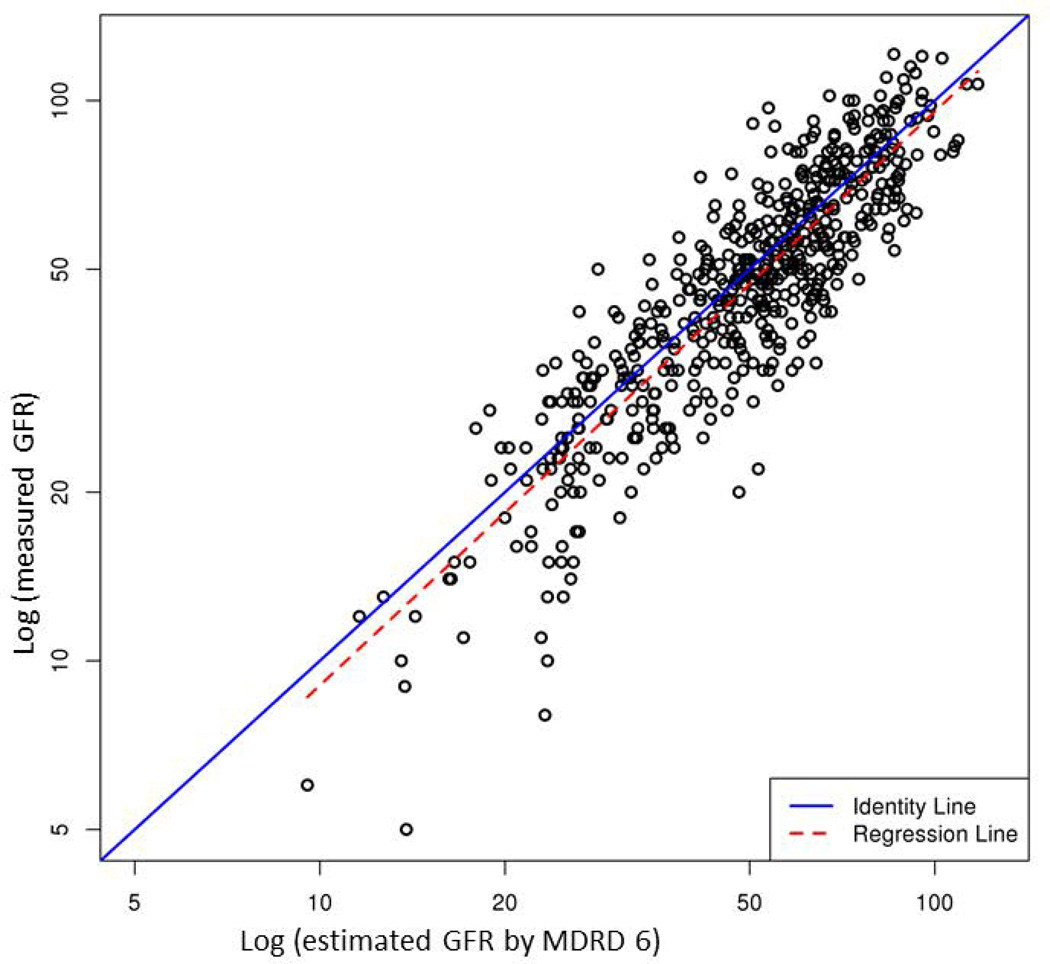

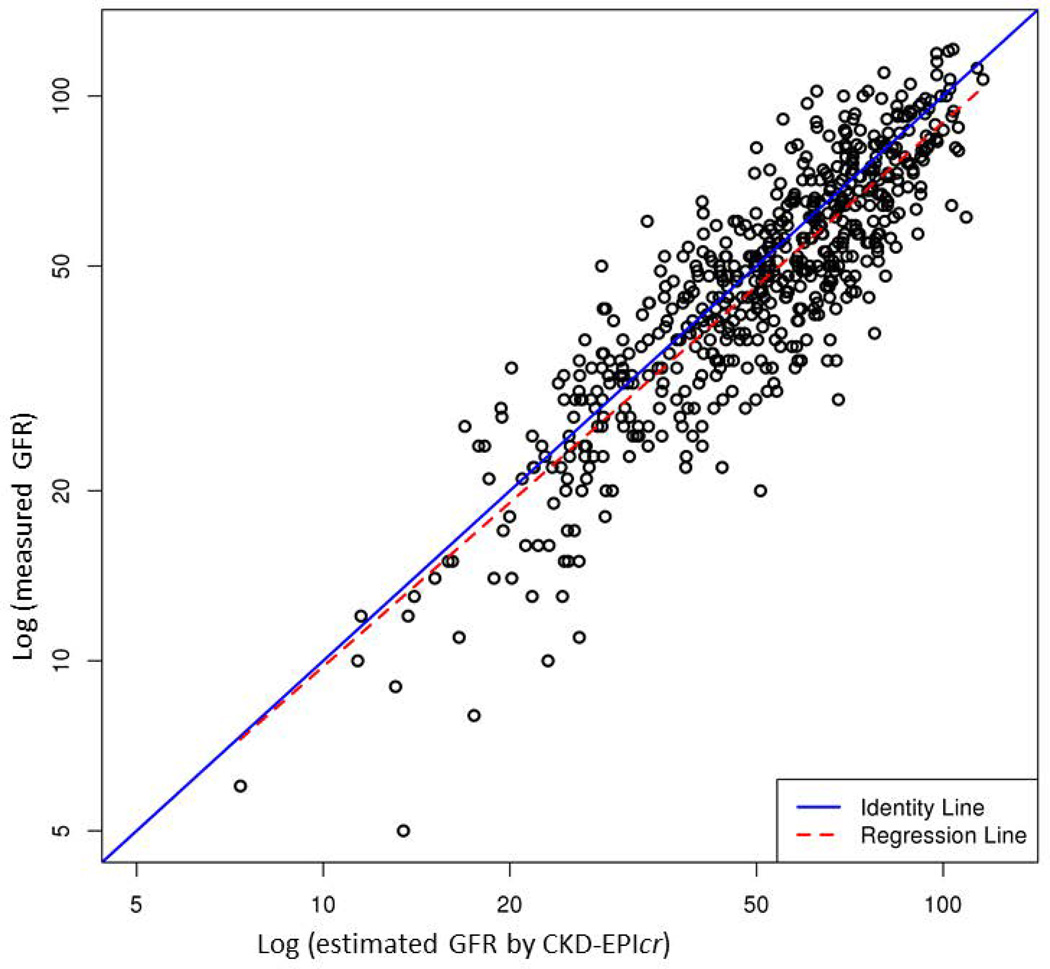

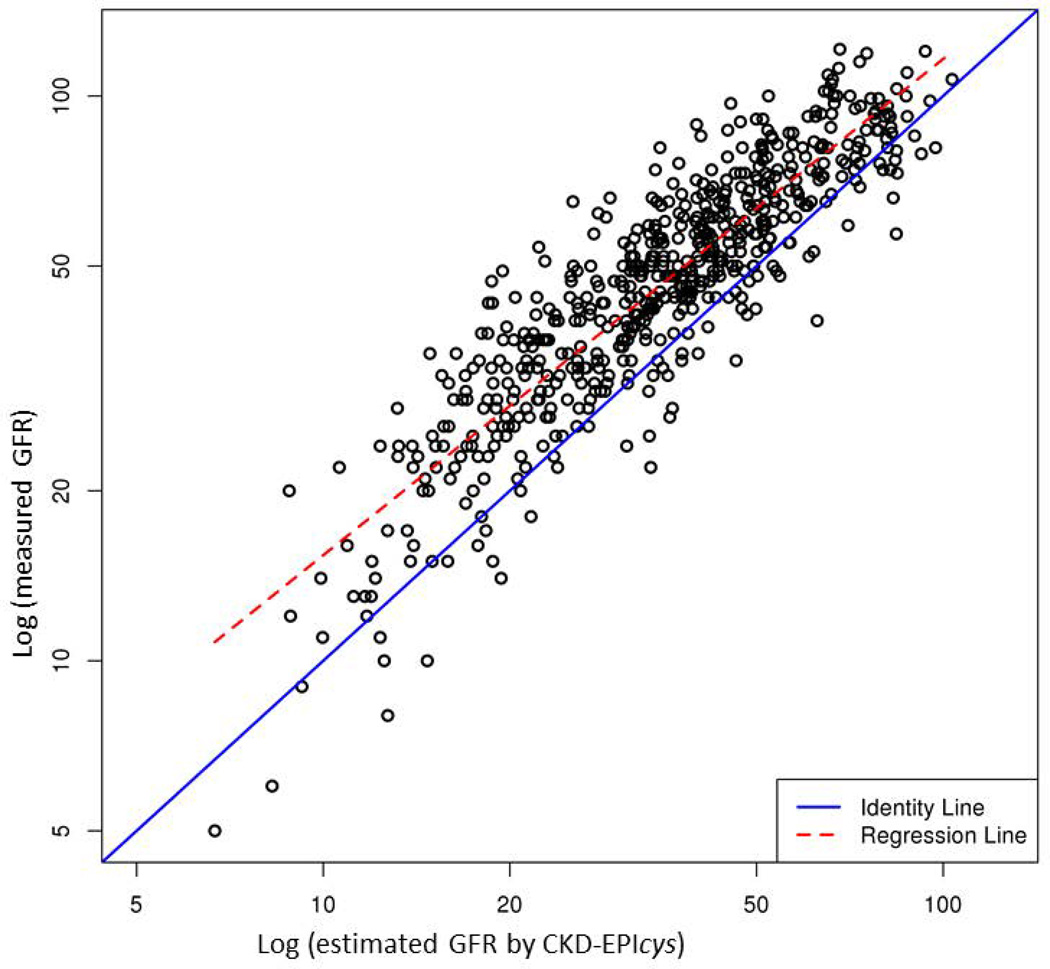

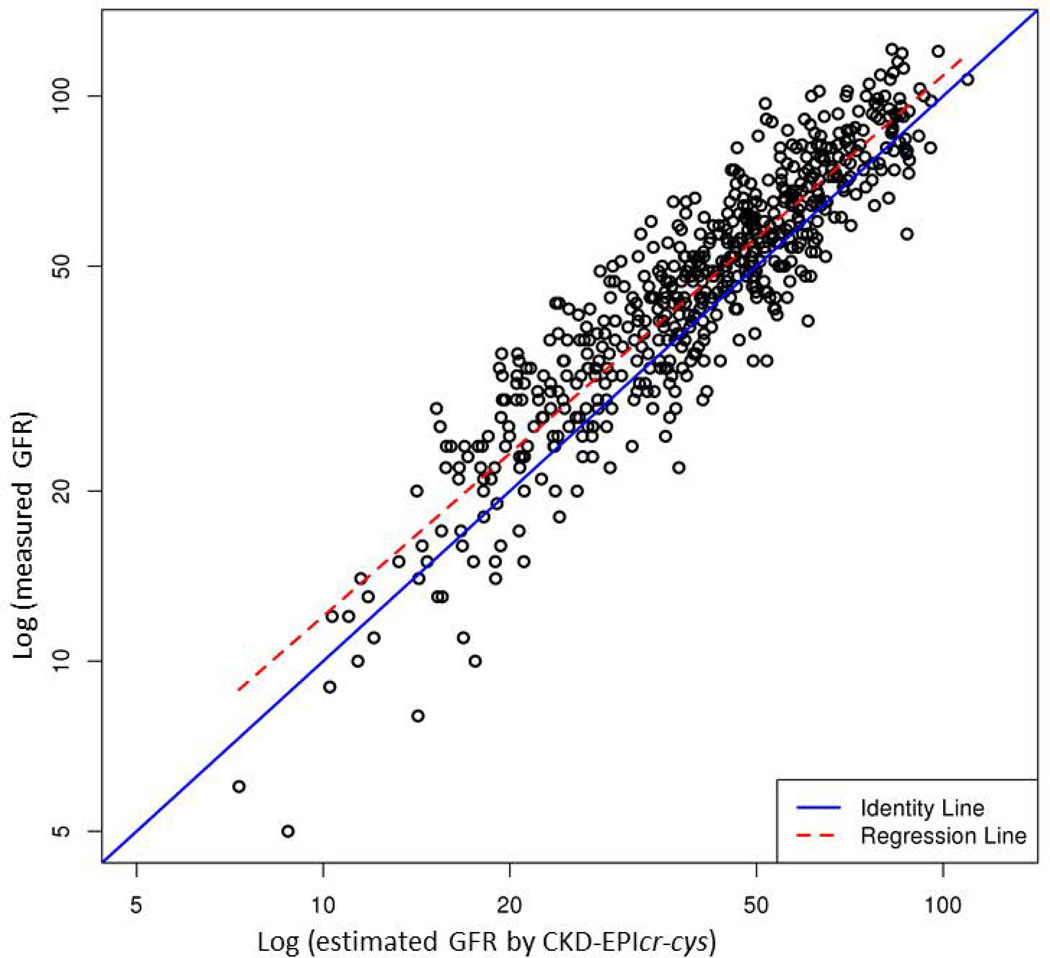

Table 2 compares performance of the five eGFR equations. Supplementary Figure illustrates the correlation between mGFR and eGFR. Of the five models, CKD-EPIcr-cys showed the highest R2 (0.83), whereas other equations containing only creatinine or cystatin C had a lower R2 (0.76 to 0.78). In terms of accuracy, CKD-EPIcr-cys had the lowest proportion of prediction that was more than 30% off the mGFR. CKD-EPIcr-cys was also most precise: the width of the interquartile range of the discrepancy between mGFR and eGFR was the narrowest with the middle 50% of the discrepancies being within 12.1 units. However, bias, measured by the average discrepancy between mGFR and eGFR was the least with MDRD 4, whereas CKD-EPIcr-cys, on average, underestimated mGFR by approximately 12%.

Table 2.

Performance comparison between equations in glomerular filtration rate estimation

| Models grouped by marker used |

R2 | Accuracy ¶ P30% (95% CI) |

Precision IQR of (mGFR-eGFR) (95% CI) |

% Bias (ln)* (95% CI) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Creatinine | MDRD 4 | 0.76 | 20.82 (17.53, 24.11) |

14.68 (13.69, 16.55) |

−0.02 (−0.04, 0.00) |

| MDRD 6 | 0.77 | 22.74 (19.20, 26.27) |

14.14 (12.64, 15.85) |

6.26 (4.20, 8.32) |

|

| CKD-EPIcr | 0.76 | 24.23 (20.76, 27.7) |

15.38 (14.03, 16.85) |

8.23 (6.24, 10.22) |

|

| Cystatin C | CKD-EPIcys | 0.78 | 40.27 (36.3, 44.24) |

13.27 (12.02, 14.63) |

−27.88 (−25.92, −29.84) |

| Creatinine- cystatin C |

CKD-EPIcr-cys | 0.83 | 15.53 (12.6, 18.46) |

12.06 (10.77, 13.38) |

−12.28 (−10.59, −13.97) |

% Bias (ln) was calculated by the formula 100 × [ln(eGFR) − ln(mGFR)]

Accuracy was calculated as the percentage of estimates that differed from the measured GFR by more than 30%

As CKD-EPIcr-cys seemed superior in three of the four criteria examined, Table 3 further considers its performance in different levels of GFR, with the idea that, in practice, tolerance for errors may be higher in subjects with normal GFR than in patients with lower GFR in whom accurate assessment of renal function is more important for management decisions. Overall, accuracy and bias were worse in patients with lower GFR. For example, only 7.6% of GFR estimates were more than 30% different from mGFR in patients with normal eGFR, whereas in patients with eGFR<30, the proportion increased to 27.8%. Similarly, in terms of bias, eGFR underestimated mGFR on average by 8.9 units in patients with normal eGFR, whereas the discrepancy increased to 16.2 units in patients with eGFR<30. Precision may seem better in the lowest GFR group; however, this may simply reflect the fact that the range of possible values in the lowest GFR tier was the narrowest. All models showed increased bias as GFR decreased (data not shown).

Table 3.

Performance of CKD-EPIcr-cys equation across ranges of glomerular filtration rate

| Variable | Estimated GFR ml/min/1.73m2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| ≤30 | 30–60 | ≥60 | |

| Accuracy - P30% (95% CI) ¶ | 27.78 (19.33, 36.23) |

15.99 (11.80, 20.18) |

7.61 (3.78, 11.44) |

|

Precision –IQR of (mGFR-eGFR) (95% CI) |

7.84 (5.78, 9.59) |

11.17 (9.80, 12.77) |

17.46 (14.65, 20.59) |

| % Bias (ln) (95% CI)* | −16.18 (−20.21, −12.15) |

−11.68 (−14.10, −9.61) |

−8.85 (−11.77, −5.93) |

% Bias (ln) was calculated by the formula 100 × [ln(eGFR) – ln(mGFR)]

Accuracy was calculated as the percentage of estimates that differed from the measured GFR by more than 30%

Next, we examined whether we could derive our own eGFR models in this patient sample which may be superior to existing eGFR equation. Supplementary Table 1 illustrates the multivariable models with and without cystatin-C. These models, however, were not demonstrably better than existing models. For example, our model that contained cystatin-C had a R2 of 0.82, compared to 0.83 for CKD-EPIcr-cys. Similarly, the R2 for our model without cystatin-C was identical to that of MDRD (0.76 both models).

Finally, Table 4 considers these various measures of renal function as predictors of mortality. All of the measures except MDRD were significantly associated with increased mortality (p=0.05 for MDRD 4 and 6). All of the eGFR models had a hazard ratio of approximately 0.5, indicating that each 10 unit increase in eGFR reduced the risk of death by roughly 50%. When the concordance statistic was used as the gauge for the strength of association with mortality, serum cystatin-C, either by itself or as a part of eGFR equation (namely CKD-EPIcys) had the strongest correlation, possibly stronger than measured GFR by iothalamate clearance.

Table 4.

Model performance in mortality prediction

| Models grouped by marker used | HR (95% CI) |

P value | Concordance statistic |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Creatinine | Serum Creatinine | 2.20 (0.97–5.04) |

0.06 | 0.58 |

| MDRD 4 | 0.52 (0.27–1.02) |

0.05 | 0.57 | |

| MDRD 6 | 0.52 (0.27–0.99) |

0.05 | 0.57 | |

| CKD-EPIcr | 0.52 (0.27–0.95) |

0.04 | 0.58 | |

| Cystatin C | CKD-EPIcys | 0.49 (0.28–0.84) |

0.01 | 0.62 |

| Serum cystatin C | 2.57 (1.23–5.40) |

0.01 | 0.62 | |

| Creatinine- cystatin C |

CKD-EPIcr-cys | 0.49 (0.27– 0.87) |

0.01 | 0.61 |

| Iothalamate clearance | 0.50 (0.30–0.83) |

0.008 | 0.61 | |

DISCUSSION

In this work, we analyzed measured GFR data in a cohort of LT recipients and evaluated various GFR-estimating equations using creatinine and cystatin C. We found a high prevalence of CKD in our patients with more than 2/3 of our patients having CKD stage 3 or higher approximately 4 years after LT. Our main results show that 1) in LT recipients, as in the general population, serum cystatin C and creatinine together substantially improve estimation of GFR over creatinine alone; 2) overall, existing eGFR equations performed comparable to the model that was derived from this data set; 3) even the best model performed suboptimally in low ranges of GFR, highlighting the need for further improvement in patients in whom accurate estimation of GFR is most needed; and 4) serum cystatin C was significantly associated with mortality.

Development of CKD after LT leads to other problems such as hypertension, anemia, malnutrition, bone disease, and a decreased quality of life (5). More importantly, it has been shown to decrease patient survival (3). In a large NIDDK study, renal dysfunction before or after liver transplantation increased patient mortality substantially (HR=2.7 for overall mortality and HR=7.5 for kidney-related death) (4). Thus, accurate assessment of GFR is essential and should be a major focus in post-LT management. Early detection of renal dysfunction may allow transplant recipients to benefit from a CKD management program.

The performance of eGFR equations varies between different patient populations (22). This is in part because serum creatinine concentration may be affected, especially in patients with systemic illness, by factors other than GFR, such as illness-related muscle wasting, fluctuating volume of distribution, and decreased hepatic production (16, 17). Serum cystatin-C concentrations are less subject to variation by these factors; however, they may be affected by inflammation (23), body fat (8) and immunosuppressive therapy (24), which may increase cystatin C production. Until recently, assays for creatinine and cystatin C were poorly standardized, which also adds to the variability in prior publications.

In our population of liver graft recipients the correlation with mGFR was stronger for cystatin C than creatinine. However, the cystatin C-based CKD-EPI equations had a tendency to underestimate GFR in our patients. While the CKD-EPIcr-cys is thought to be relatively unbiased in non-transplant populations, we found that it underestimates GFR by about 12%. This was consistent with observations by the developers of CKD-EPI equations, which led them not to include transplant recipients in the sample used to derive the cystatin C-based CKD-EPI equation (14). Prior studies have shown that liver or kidney transplant recipients have higher cystatin C levels given the same GFR compared to non-transplant recipients (18). It has been postulated that increased cystatin-C production by exogenous glucocorticoids or greater inflammation in transplant recipients may increase serum concentrations of cystatin C. We believe, in our data, the impact of glucocorticoid use was minimal because our standard posttransplant immunosuppression protocol includes glucocorticoids only for a short period on time. Prednisone was tapered rapidly and discontinued by day 120 posttransplant, whereas this study was conducted after 4 years following LT on average. With regard to inflammation, we lacked suitable markers such as sedimentation rate or CRP to evaluate its influence on serum cystatin-C.

Our data suggest that in LT recipients, both creatinine and cystatin-C have limitations as a biomarker of renal function and the two may be complementary to each other, which may explain why equations that contain both markers performed better than those with either alone. The CKD-EPIcr-cys is essentially an average of the CKD-EPIcr and CKD-EPIcys equations. Since the CKD-EPIcys equation underestimates GFR to a greater extent than the CKD-EPIcr overestimates GFR, the net effect of the CKD-EPIcr-cys is tendency for underestimation of GFR.

CKD-EPI equations, derived from heterogeneous groups of subjects and advocated by the KDIGO guidelines in evaluation of patients with CKD, have not been evaluated in liver graft recipients prior to this study. In routine practice, the MDRD equation is being ubiquitously used. It was somewhat surprising that, compared to these two eGFR equations, the eGFR models that were developed from this patient sample were not any better. Moreover, it is noteworthy that the bias of all models becomes worse as GFR declines. Based on these data, we make the following recommendation for clinicians managing LT recipients: 1) if assays are available, formulas containing cystatin-C (e.g., CKD-EPIcr-cys) provide better assessment of GFR; 2) if cystatin-C is not available, the MDRD 4 equation, given its wide availability, appears the most reasonable one to use; 3) all of the formulas we evaluated had diminishing accuracy in patients in low GFR; and 4) thus, continued research is needed for better clinical tools for assessment renal function in our patient population.

It was previously shown that the degree to which eGFR formulas correlate to mGFR may not necessarily translate to accurate prediction of hard end points such as mortality and kidney failure (25). For example, in non-transplant populations, eGFR formulas correlating closely to mGFR were not necessarily better predictive of CKD risk factors and outcomes (26) (27, 28). As renal dysfunction is an established risk factor for mortality, it remains to be determined whether cystatin C may predict mortality over and beyond its effect on GFR estimation in the posttransplant setting. Cystatin C, either as an individual marker or as part of a GFR estimating equation, was a better predictor of death from all causes and cardiovascular events across diverse populations (10, 29).

In a prior study conducted in our LT patients, the main causes of death included malignancy, followed by graft failure, infections and cardiovascular events (3). In this cohort of liver graft recipients, the association of cystatin C with mortality was stronger than that of creatinine-based equations and, at least numerically, than that of measured GFR. We postulate that this may be related to non-GFR determinants of cystatin-C, such as inflammation, obesity and diabetes. While this analysis was not designed to test this hypothesis, it does suggest that serum cystatin C carries prognostic information which is beyond its correlation with GFR.

In conclusion, combined equations using serum creatinine and serum cystatin C provide a more accurate estimation of GFR after liver transplantation than equations using either of the markers alone. As assays for cystatin-C become more widely available, practitioners may consider incorporating its serum level in assessment of LT patients, either for estimation of GFR or for assessment of general health risk. All of these models, however, have limited accuracy in patients in low GFR, in whom accurate assessment of renal function is most helpful. Continued research is needed for better clinical tools for assessment renal function in this patient population.

METHODS

Study design and subjects

This is a cross-sectional study of adult liver transplant recipients prospectively followed at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota from 1988 to 2010. Measured GFR (mGFR) by iothalamate clearance was performed periodically as part of standardized post-LT evaluations, which also included measurement of serum creatinine levels. Biochemical data were extracted from an electronic database that tracks LT patients. We included all available mGFR results, as some patients had more than one measurement during follow-up. Serum cystatin-C was measured on stored serum samples obtained at the time of mGFR testing or within 48 hours. The study protocol was approved by Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board.

Data collection

GFR measurement by iothalamate clearance has been described previously in detail (30, 31). Briefly, the method consisted of subcutaneous injection of iothalamate after oral hydration. After approximately one hour, urine (U) and plasma (P) iothalamate level, as well as urine volume (V) are measured, and GFR calculated by the iothalamate clearance formula UV/P. The results are normalized to ml/min/1.73 m2 of body surface area using the height-and weight-based Dubois formula (32).

Banked serum samples were retrieved and cystatin C was assayed by immunoturbidometry (Gentian AS, Norway), which has a coefficient of variation of 5.0%. This cystatin C immunoassay was calibrated against the new cystatin C World Standard reference material ERM-DA471/IFCC (33).

Concurrent laboratory data and demographic information were extracted from the prospective database. These included age, sex, race, time since transplant, median creatinine, albumin and blood urea nitrogen (BUN). Serum creatinine was measured by a Rate-Jaffe assay from 1988–2006 and by a standardized Roche enzymatic assay (Roche Cobas creatinine reagent, Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis IN) from 2006–2010. Serum creatinine results from 1988–2006 were re-calibrated by subtracting 0.14 mg/dL from the original value, in concordance with the serum creatinine assay standardization in October 2006 (34).

Statistical Methods

For the first aim, the extent to which the addition of serum cystatin-C improves the accuracy of GFR estimation was evaluated by comparing the performance of the following eGFR models (Supplementary Table 2): CKD-EPIcr (35), MDRD-4 (36), MDRD-6 (37), CKD-EPIcys, and CKD-EPIcr-cys (14). We used four measures in this comparison. The first metric to assess model fit was R2, the proportion of variability explained by the model. Accuracy was calculated as the proportion of estimates that differed from mGFR by more than 30% (P30%). Precision was assessed as the interquartile range for the difference between mGFR and eGFR. Bias was calculated as the average discrepancy 100×[ln(eGFR) – ln(mGFR)]. These same parameters were further considered for subgroups defined by ranges of eGFR (<30, 30–60, >60 ml/min/1.73m2).

For the second aim, we created two eGFR equations-one with and the other without cystatin-C. Besides serum creatinine and cystatin C, candidate variables to be considered in the model were limited to routinely available clinical data that have a biologically plausible reason for correlation with mGFR. These included age, sex, BUN and albumin. Since the vast majority of our patients were white without sufficient number of non-white subjects, race was not considered in the models. In implementing the models, the linear regression analysis was performed on log-transformed data. For ease of interpretation and comparison with other eGFR formulas, the equations were converted to express GFR in natural scale.

In the third aim of the study, we assessed the role of serum cystatin-C as a predictor of mortality. Using the Cox regression analysis, we compared the GFR estimating models considered in the first aim, as well as serum cystatin C level and measured GFR as predictors of mortality. Concordance statistics were used to compare model performance. Statistical analysis was performed with SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC).

Supplementary Material

Figure.

Correlation between measured GFR by iothalamate clearance (y-axis) and estimated GFR by each of the 5 equations (x-axis): (A) MDRD 4, (B) MDRD 6, (C) CKD-EPIcr, (D) CKD-EPIcys and (E) CKD-EPIcr-cys. Points indicate individual subjects.

Acknowledgments

Financial support: National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases DK-34238 and DK92336 (WRK).

Abbreviations

- GFR

glomerular filtration rate

- CKD

chronic kidney disease

- LT

liver transplant

- MDRD

Modification of Diet in Renal Disease

- CKD-EPI

Chronic Kidney Disease Epidemiology Collaboration

- cr

creatinine

- cys

cystatin

- CI

confidence interval.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors of this manuscript have no conflicts of interest to disclose as described by Transplantation.

Author contributions:

Alina M. Allen: study concept and design, data analysis and interpretation, writing of the manuscript

W. Ray Kim: study concept and design, data analysis and interpretation, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content, study supervision

Joseph J. Larson: acquisition of data, statistical analysis

Colin Colby: acquisition of data, statistical analysis

Terry M. Therneau: study concept and design, data analysis and interpretation, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

Andrew D. Rule: data analysis and interpretation, critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content

REFERENCE LIST

- 1.Ojo AO, Held PJ, Port FK, et al. Chronic renal failure after transplantation of a nonrenal organ. The New England journal of medicine. 2003;349(10):931. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Riordan A, Dutt N, Cairns H, et al. Renal biopsy in liver transplant recipients. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation. 2009;24(7):2276. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen AM, Kim WR, Therneau TM, Larson JJ, Heimbach JK, Rule AD. Chronic kidney disease and associated mortality after liver transplantation - a time-dependent analysis using measured glomerular filtration rate. Journal of hepatology. 2014;61(2):286–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.03.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Watt KD, Pedersen RA, Kremers WK, Heimbach JK, Charlton MR. Evolution of causes and risk factors for mortality post-liver transplant: results of the NIDDK long-term follow-up study. American journal of transplantation : 2010;10(6):1420. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2010.03126.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group. KDIGO 2012 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Evaluation and Management of Chronic Kidney Disease. Kidney inter, Suppl. 2013;3:1. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gonwa TA, Jennings L, Mai ML, Stark PC, Levey AS, Klintmalm GB. Estimation of glomerular filtration rates before and after orthotopic liver transplantation: evaluation of current equations. Liver transplantation. 2004;10(2):301. doi: 10.1002/lt.20017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tangri N, Alam A, Edwardes MD, Davidson A, Deschenes M, Cantarovich M. Evaluating cimetidine for GFR estimation in liver transplant recipients. Nephrology, dialysis, transplantation. 2010;25(4):1285. doi: 10.1093/ndt/gfp627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chew-Harris JS, Florkowski CM, George PM, Elmslie JL, Endre ZH. The relative effects of fat versus muscle mass on cystatin C and estimates of renal function in healthy young men. Annals of clinical biochemistry. 2013;50(Pt 1):39. doi: 10.1258/acb.2012.011241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Menon V, Shlipak MG, Wang X, et al. Cystatin C as a risk factor for outcomes in chronic kidney disease. Annals of internal medicine. 2007;147(1):19. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-147-1-200707030-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shlipak MG, Matsushita K, Arnlov J, et al. Cystatin C versus creatinine in determining risk based on kidney function. The New England journal of medicine. 2013;369(10):932. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1214234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Francoz C, Nadim MK, Baron A, et al. Glomerular filtration rate equations for liver-kidney transplantation in patients with cirrhosis: validation of current recommendations. Hepatology. 2014;59(4):1514. doi: 10.1002/hep.26704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.De Souza V, Hadj-Aissa A, Dolomanova O, et al. Creatinine- versus cystatine C-based equations in assessing the renal function of candidates for liver transplantation with cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2014;59(4):1522. doi: 10.1002/hep.26886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mindikoglu AL, Dowling TC, Weir MR, Seliger SL, Christenson RH, Magder LS. Performance of chronic kidney disease epidemiology collaboration creatinine-cystatin C equation for estimating kidney function in cirrhosis. Hepatology. 2014;59(4):1532. doi: 10.1002/hep.26556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Inker LA, Schmid CH, Tighiouart H, et al. Estimating glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine and cystatin C. The New England journal of medicine. 2012;367(1):20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1114248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stevens LA, Coresh J, Schmid CH, et al. Estimating GFR using serum cystatin C alone and in combination with serum creatinine: a pooled analysis of 3,418 individuals with CKD. American journal of kidney diseases. 2008;51(3):395. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sherman DS, Fish DN, Teitelbaum I. Assessing renal function in cirrhotic patients: problems and pitfalls. American journal of kidney diseases. 2003;41(2):269. doi: 10.1053/ajkd.2003.50035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Francoz C, Prie D, Abdelrazek W, et al. Inaccuracies of creatinine and creatinine-based equations in candidates for liver transplantation with low creatinine: impact on the model for end-stage liver disease score. Liver transplantation. 2010;16(10):1169. doi: 10.1002/lt.22128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bokenkamp A, Domanetzki M, Zinck R, Schumann G, Byrd D, Brodehl J. Cystatin C serum concentrations underestimate glomerular filtration rate in renal transplant recipients. Clinical chemistry. 1999;45(10):1866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schuck O, Gottfriedova H, Maly J, et al. Glomerular filtration rate assessment in individuals after orthotopic liver transplantation based on serum cystatin C levels. Liver transplantation. 2002;8(7):594. doi: 10.1053/jlts.2002.33957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerhardt T, Poge U, Stoffel-Wagner B, et al. Estimation of glomerular filtration rates after orthotopic liver transplantation: Evaluation of cystatin C-based equations. Liver transplantation. 2006;12(11):1667. doi: 10.1002/lt.20881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rule AD, Bergstralh EJ, Slezak JM, Bergert J, Larson TS. Glomerular filtration rate estimated by cystatin C among different clinical presentations. Kidney international. 2006;69(2):399. doi: 10.1038/sj.ki.5000073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Stevens LA, Coresh J, Greene T, Levey AS. Assessing kidney function--measured and estimated glomerular filtration rate. The New England journal of medicine. 2006;354(23):2473. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra054415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cimerman N, Brguljan PM, Krasovec M, Suskovic S, Kos J. Serum cystatin C, a potent inhibitor of cysteine proteinases, is elevated in asthmatic patients. Clinica chimica acta; international journal of clinical chemistry. 2000;300(1–2):83. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(00)00298-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Risch L, Herklotz R, Blumberg A, Huber AR. Effects of glucocorticoid immunosuppression on serum cystatin C concentrations in renal transplant patients. Clinical chemistry. 2001;47(11):2055. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rule AD, Glassock RJ. GFR estimating equations: getting closer to the truth? Clinical journal of the American Society of Nephrology : CJASN. 2013;8(8):1414. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01240213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rule AD, Bailey KR, Lieske JC, Peyser PA, Turner ST. Estimating the glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine is better than from cystatin C for evaluating risk factors associated with chronic kidney disease. Kidney international. 2013;83(6):1169. doi: 10.1038/ki.2013.7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Astor BC, Levey AS, Stevens LA, Van Lente F, Selvin E, Coresh J. Method of glomerular filtration rate estimation affects prediction of mortality risk. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2009;20(10):2214. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2008090980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mathisen UD, Melsom T, Ingebretsen OC, et al. Estimated GFR associates with cardiovascular risk factors independently of measured GFR. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology : JASN. 2011;22(5):927. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2010050479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ix JH, Shlipak MG, Chertow GM, Whooley MA. Association of cystatin C with mortality, cardiovascular events, and incident heart failure among persons with coronary heart disease: data from the Heart and Soul Study. Circulation. 2007;115(2):173. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.644286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wilson DM, Bergert JH, Larson TS, Liedtke RR. GFR determined by nonradiolabeled iothalamate using capillary electrophoresis. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 1997;30(5):646. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(97)90488-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rule AD, Gussak HM, Pond GR, et al. Measured and estimated GFR in healthy potential kidney donors. American journal of kidney diseases : the official journal of the National Kidney Foundation. 2004;43(1):112. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2003.09.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Du Bois D, Du Bois EF. A formula to estimate the approximate surface area if height and weight be known. 1916. Nutrition. 1989;5(5):303. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Voskoboev NV, Larson TS, Rule AD, Lieske JC. Analytic and clinical validation of a standardized cystatin C particle enhanced turbidimetric assay (PETIA) to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Clinical chemistry and laboratory medicine : CCLM / FESCC. 2012;50(9):1591. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2012-0063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T, et al. Expressing the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate with standardized serum creatinine values. Clinical chemistry. 2007;53(4):766. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2006.077180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Levey AS, Stevens LA, Schmid CH, et al. A new equation to estimate glomerular filtration rate. Annals of internal medicine. 2009;150(9):604. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-150-9-200905050-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.K/DOQI clinical practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation, classification, and stratification. American journal of kidney diseases. 2002;39(2 Suppl 1):S1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N, Roth D. A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of Diet in Renal Disease Study Group. Annals of internal medicine. 1999;130(6):461. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-130-6-199903160-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.