Approximately 49.9 million people in the United States lack health insurance (DeNavas-Walt, Proctor and Smith (2011)). One potential driver of uninsurance is asymmetric information on health risk between insurers and the insured. Asymmetric information can distort available insurance contracts, as in Rothschild and Stiglitz (1976), or it can raise premiums for the relatively healthy, as in Akerlof (1970). Both distortions result in in-efficiently low levels of insurance coverage.

Predicated, at least in part, on concerns about adverse selection, the state of Massachusetts passed health reform in April 2006 aimed at achieving near-universal health insurance coverage. The Massachusetts approach is considered a model for national health reform, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (PPACA), signed in March 2010. A central feature of both reforms is a mandate that individuals obtain health insurance or pay a penalty. The Massachusetts mandate allows us to examine whether there was adverse selection into health insurance before the reform. In contrast, existing literature generally examines adverse selection among employer-sponsored plans (e.g. Cutler and Reber (1998); Einav, Finkelstein and Cullen (2010)), which is less relevant for policy.

Our simple empirical methodology is based on the observation that the direction of selection depends on the difference between the cost of the marginal enrollee and the cost of those who already have insurance. If the cost of the marginal enrollee is below the average cost of those who are already insured, selection is adverse; if the cost of the marginal enrollee is above the average cost of those who are already insured, selection is advantageous. Therefore, as demonstrated by Einav, Finkelstein and Cullen (2010), the sign of the slope of the average cost curve captures selection.

We use the Massachusetts reform to provide an exogenous shift in coverage that identifies the slope of the average cost curve. We find that counties with larger increases in coverage over the reform period face the smallest increase in average hospital costs for the insured population, consistent with adverse selection into insurance before reform. Additional results that incorporate cross-state variation and data on health measures provide further evidence for adverse selection.

I. Test for Selection

Our primary test for adverse selection relies on county level variation in coverage. All Massachusetts counties reached near-universal insurance coverage through the reform, but some counties were more affected by the reform than others because of different initial levels of coverage. We estimate the following model

| (1) |

where Yct measures average hospital costs per insured inhabitant of county c in year t, and I captures insurance coverage. δt and μc control for fixed effects by year and county. We estimate equation (1) via TSLS where the set of instruments is given by the interaction of a post-reform indicator and county fixed effects, such that county-specific changes in coverage over the reform period are the only source of identifying variation.

Under adverse selection, we expect α < 0: an increase in insurance coverage improves the pool of the insured risks and decreases the average costs per insuree. Conversely, under advantageous selection, the average cost of the insured grows as the pool expands: α > 0. Our primary specification focuses on hospital cost as the dependent variable because asymmetric information is important for insurance insofar as it translates into cost. Furthermore, we can observe the universe of hospital costs in Massachusetts, and hospital costs account for the majority of medical spending.

To understand the mechanisms behind our cost results, we examine health measures and behaviors. We estimate variants of equation (1) where Y represents measures of the average health of the insured. Depending on the correlation between the health measures and cost, the sign of α is a test for selection. If there is adverse selection, we expect the rate of diabetes (a health measure that should be positively correlated with costs) to decline in the insured population. In contrast, we expect the rate of regular exercise (a measure that should be negatively correlated with costs) to grow. If health insurance improves our measures of health, we will be biased against finding adverse selection.

We can also test for adverse selection by comparing Massachusetts to other states. We re-estimate equation (1) replacing counties by states. Our instrument for insurance coverage is then the interaction of a post-reform indicator and a Massachusetts indicator.

II. Data

A. Case Mix Data

We observe the universe of hospital discharges before and after the reform in the Massachusetts Case Mix Data from 2004 to 2009. The data provide information on insurance coverage for every hospital discharge.1 The data also provide information on the total charges for each discharge, which we convert to costs using the HCUP cost-to-charge ratio. We prefer costs to charges because charges reflect prices, and hospitals might have changed their prices following reform. We deflate hospital costs into 2011 dollars using the medical care consumer price index provided by the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS).

We focus on hospital costs for nonelderly insured patients aged 18–64. Using the patient zip code, we aggregate hospital costs to the county-year level. To estimate the average hospital costs for all insured inhabitants, including those who do not visit the hospital, we incorporate additional data. For pre-reform coverage levels, we use the Small Area Health Insurance Estimates (SAHIE) from 2005 by county. For post-reform coverage levels, we use the 2008 and 2009 estimates from the American Community Survey (ACS), which is based on a much larger sample size than the SAHIE but is only available starting in 2008. In all analyses, we drop the reform implementation years 2006 and 2007. We use the Census for county population estimates.

B. BRFSS Data

We complement the hospital cost data with health measures from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS). We use average health measures for the insured population at the state-year level from 2004–2005 and 2008–2010. We rely on random sample selection into the BRFSS, which allows us to compare health measures for the insured sample population directly, eliminating the need to merge coverage and population estimates from additional sources. We do not weight the average health measures or the average insurance coverage of the sampled population in our health regressions. We drop Dukes and Nantucket counties from all analyses because the BRFFS does not provide information on them in the pre-reform years.

III. Results

A. Hospital Costs

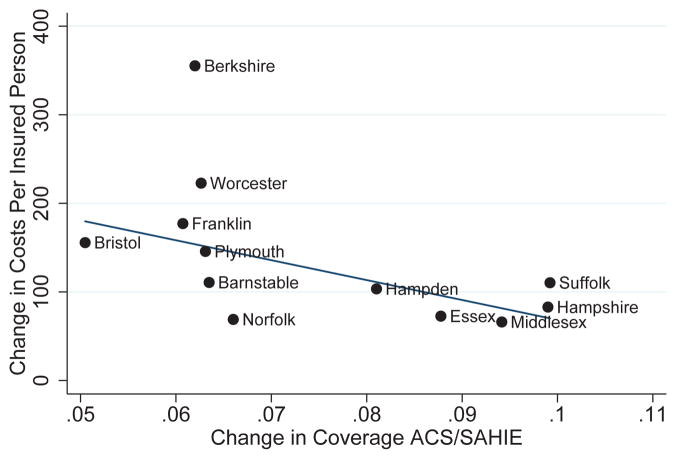

We compute the average hospital costs and the average insurance coverage by county for two periods: 2004–2005 and 2008–2009, and we plot the difference in each measure between the two periods in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Evidence by County

The linear fit weights counties by population size. We see a pronounced negative relationship, which suggests that counties that saw greater increases in coverage faced smaller increases in average costs per insured resident, consistent with adverse selection.

The first column of Table 1 shows the corresponding IV estimate. The coefficient is negative and statistically significant. If we assume that equation (1) describes the average cost function, we can interpret the point estimate as the average hospital expenditure of the insured population as we move from no insurance to full insurance. Moving from the first (most expensive) enrollee to full insurance coverage reduces hospital costs by approximately $2,250 (about 50% of the 2006 average premium for employer-sponsored health insurance, according to KFF (2006)). To translate this coefficient into the observed change in average costs, we need an estimate of the coverage increase. First stage regression results at the state level from the BRFFS suggest that because of health reform, insurance coverage in Massachusetts increased by 5.5%.2 Scaling the point estimate by the increase in coverage suggests that because of adverse selection, health reform reduced the annual average hospital costs for the insured Massachusetts population by about $124 (0.055 × $2,247) per person, approximately 3% of the 2006 average premium for employer-sponsored health insurance.

Table 1.

Evidence by County

| IV | OLS | |

|---|---|---|

| Coverage | −2247.4* (−2.18) | 37.49 (0.03) |

| N | 48 | 24 |

t statistics in parentheses, clustered at the county level.

p < 0.10,

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01

The second column of Table 1 presents results from a county-year level OLS regression, which uses cross-sectional variation in the pre-reform period. The coefficient estimate is positive, suggesting that without the reform-induced variation differences across counties provide spurious evidence for advantageous selection.

B. Health Measures and Behaviors

Table 2 displays the impact of reform on various measures of health of the insured population aged 18–64, using variation by state. Signs of six of the seven health measures are consistent with adverse selection, and five of these are statistically significant. Results at the county level, not reported here, are broadly consistent: signs of six of the seven coefficients suggest adverse selection, but they are not statistically significant, likely reflecting the small sample size at the county level in the BRFSS.

Table 2.

Evidence by State

| Coverage | t statistic | |

|---|---|---|

| Days Health Not Good | −2.413*** | (−2.98) |

| Health Prevented Activity | 1.869 | ( 1.50) |

| Exercise | 0.297*** | ( 4.30) |

| Disability | −0.213*** | (−4.22) |

| Need Equipment | −0.125*** | (−5.22) |

| Diabetes | −0.0489** | (−2.29) |

| Asthma | −0.0536 | (−1.65) |

clustered at the state level.

p < 0.10,

p < 0.05,

p < 0.01

IV. Conclusion

Our results suggest that increased coverage due to reform in Massachusetts lowered average hospital costs for the insured, and thus average premiums before loading, by about $124. This impact, which represents an average premium change over all types of insurance, is consistent with the aggregate change in premiums in Massachusetts. Between 2006 and 2009, premiums in employer-sponsored plans followed the national trend, but premiums in the non-group market decreased by 20% (Gruber (2011)), comparable to the 3% overall decrease in premiums that we observe.

Our results also shed light on an important question for insurers and policy makers facing the introduction of the PPACA: who is likely to sign up for coverage, particularly through new health insurance exchanges? However, to generalize our results from the Massachusetts to the national reform, we should note that Massachusetts had “community rating” regulations that limited the ability of insurers to price based on health status in the non-group health insurance market before the reform. These regulations could have increased asymmetric information, leading to adverse selection and higher premiums. In contrast, much of the country does not currently have community rating regulations, but the PPACA institutes them along with the mandate.

Despite differences in the community rating environments between Massachusetts and the nation, our findings are broadly consistent with the CBO predictions for national reform: premium changes from −1 to 2% in the small group market and from −3 to 0% in the large group market (CBO 2009). Comparison with the CBO estimates suggests that large impacts of community rating in the non-group market could be masked by changes in the employer market, unsurprising given that only 5% of the insured in Massachusetts were in the non-group market before and after reform (Kolstad and Kowalski (2010)).

The existence of community rating prior to reform also makes the Massachusetts experience relevant in the case that the Supreme Court finds the individual mandate unconstitutional but upholds the community rating regulations. Our results suggest that a partial implementation of PPACA could result in an adversely selected market, leading premiums to fall by less than they otherwise would or even increase.

We have demonstrated that there was adverse selection into health insurance in Massachusetts before the reform. While this allows us to address some policy relevant questions, our simple sign test does not quantify the magnitude of the welfare cost of adverse selection. In ongoing work we extend this approach to estimate welfare losses due to adverse selection.

Acknowledgments

Funding from the NBER Household Finance Working Group through the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, the National Institute on Aging grant #P30 AG012810, the Leonard Davis Institute for Health Economics, and the Wharton Deans Research Fund are gratefully acknowledged.

Footnotes

We only consider variation in coverage between the insured and the uninsured, and not between different insurance contracts. Thus, our underlying model of adverse selection is consistent with Akerlof (1970).

This weighted coverage increase is consistent with estimates from other sources, reported in Kolstad and Kowalski (2010).

Contributor Information

Martin B. Hackmann, Department of Economics, Yale University

Jonathan T. Kolstad, Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania and NBER

Amanda E. Kowalski, Department of Economics, Yale University, NBER, and Brookings

References

- Akerlof George A. The Market for “Lemons”: Quality Uncertainty and the Market Mechanism. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1970;84(3):488–500. [Google Scholar]

- Congressional Budget Office. An Analysis of Health Insurance Premiums Under the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. Washington, DC: 2009. Nov 30, Available from: http://www.cbo.gov/ftpdocs/107xx/doc10781/11-30-Premiums.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Cutler David M, Reber Sarah J. Paying for Health Insurance: The Trade-Off between Competition and Adverse Selection. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1998;113(2):433–466. [Google Scholar]

- DeNavas-Walt Carmen, Proctor Bernadette D, Smith Jessica C. US Census Bureau, Current Population Reports. U.S. Government Printing Office; Washington, DC: 2011. Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2010; pp. 60–239. [Google Scholar]

- Einav Liran, Finkelstein Amy, Cullen Mark. Estimating Welfare in Insurance Markets Using Variation in Prices. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2010;125(3):877–921. doi: 10.1162/qjec.2010.125.3.877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruber Jonathan. Massachusetts Points the Way to Successful Health Care Reform. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management. 2011;30(1):184–192. [Google Scholar]

- Kaiser Family Foundation. Employer Health Benefits. Menlo Park, CA: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Kolstad Jonathan T, Kowalski Amanda E. The Impact of an Individual Health Insurance Mandate on Hospital and Preventive Care: Evidence from Massachusetts. NBER Working Paper 16012 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Rothschild Michael, Stiglitz Joseph. Equilibrium in Competitive Insurance Markets: An Essay on the Economics of Imperfect Information. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 1976;90(4):629–650. [Google Scholar]