Abstract

Background

Postcurettage void augmentation in the management of hand enchondroma is a debated practice. The objectives of this study are to present the outcomes of hand enchondroma treatment by curettage without void augmentation at the authors’ institution and to systematically review the literature pertinent to this aspect of management.

Methods

Initially, a retrospective case series of patients treated for hand enchondroma at the authors’ institution was conducted to assess postoperative complications and radiographic consolidation. All patients were treated by curettage without void augmentation. Next, a systematic review was conducted. Postcurettage void management was categorized into four groups: (1) curettage alone, (2) curettage followed by augmentation with cancellous autograft, (3) curettage followed by augmentation with bioactive and osteoconductive materials other than autograft, and (4) curettage followed by augmentation with bone cements. Complication and recurrence rates were compared.

Results

The authors’ series was composed of 24 patients with 26 lesions. The mean age was 38.9 years (range 14–61), and the mean follow-up was 26 months (range 3–120). There was one recurrence but no postoperative fractures or nonunions. As for the systematic review, a total of 22 studies involving 591 patients and 609 lesions were assessed. Complications occurred at an incidence of 0.7 % following curettage alone, 3.5 % following autograft, 0 % following augmentation with bioactive/osteoconductive materials, and 2.0 % following cement augmentation. No statistical differences were noted for complication or recurrence rates.

Conclusions

Simple curettage is an effective and inexpensive technique that does not lead to increased complication rates in the treatment of most hand enchondromas.

Keywords: Benign, Cartilaginous tumor, Enchondroma, Hand

Introduction

Enchondroma is a benign, intramedullary, cartilaginous tumor and is the most common bone tumor of the hand. It often presents in the third and fourth decades of life [6, 9, 11, 12, 14, 16, 21, 29, 33], has a predilection for the ulnar sided tubular bones of the hand, and arises most frequently in the phalanges and metacarpals [5, 8, 25]. Malignant degeneration is exceedingly rare [4] but has been reported most often in conjunction with Ollier’s or Maffucci’s syndromes [2, 26].

Curettage is the well-accepted definitive form of treatment for hand enchondromas. However, management of the resultant bone cavity remains a topic of debate. Some surgeons advocate simple curettage [11, 12, 21, 27, 28, 30–33] while others recommend curettage followed by void augmentation with biological or synthetic fillers [1–3, 6, 7, 9, 13–16, 29, 34]. Proponents of curettage alone contend that augmentation is an extraneous step that is unnecessary for the prevention of postoperative fractures or recurrence and carries significant risks or disadvantages: donor site morbidity when an autologous bone graft is used, added surgical time and expense, and the introduction of a foreign body material when allografts and synthetic materials are used. On the other hand, advocates of void filling and augmentation propose that defect filling may provide early structural support (in the case of bone cement) or an osteoconductive environment that could facilitate more rapid bone healing and decrease the likelihood of postoperative fracture and recurrence [1, 2, 6, 9, 13, 14, 16, 20, 29, 34]. To date, no comprehensive study has demonstrated superiority of curettage and augmentation over curettage without augmentation.

The objectives of this study are to analyze the efficacy and safety of curettage alone at the authors’ institution and to systematically review the literature on hand enchondromas and compare the results of (1) curettage alone, (2) curettage followed by augmentation with cancellous autograft, (3) curettage followed by augmentation with bioactive and osteoconductive materials other than autograft, and (4) curettage followed by augmentation with bone cements (materials that provide immediate structural support). It is hypothesized that there are no differences in postoperative complication rates among the various categories of treatment.

Materials and Methods

Case Series

A retrospective review was conducted using the clinical records and radiographs of patients with single or multiple enchondromas of the hand treated between January 1989 and October 2013 at the authors’ institution. Institutional review board approval was acquired for this study; however, patient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study. International Classification of Diseases (ICD-9) and Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes were used to identify the patients of interest. Patients with a confirmed histological diagnosis of enchondroma in the hand treated by the senior author were included in the study. The following exclusion criteria were applied: patients who had less than 3 months of follow-up (n = 2), patients with missing medical records (n = 1), nonoperative treatment (n = 1), curettage followed by void augmentations (n = 1), previous enchondroma surgery performed at an outside institution (n = 1), patients with Ollier’s disease as these patients tend to have a high recurrence rate (n = 1), skeletally immature patients (n = 1), and patients with previous open reduction and internal fixation of a phalanx fracture that subsequently developed an enchondroma (n = 1). Basic demographic data, the presence of postoperative complications, and recurrence were evaluated during the follow-up visits. Furthermore, the radiographic dimensions of each lesion were measured using preoperative posteroanterior (PA) and lateral radiographs. Lesion size was measured in millimeters as the proximal-to-distal length (PA view) multiplied by the medial-to-lateral width (PA view) multiplied by the volar-to-dorsal depth on lateral radiographs. Complete radiographic consolidation was defined as the presence of bridging callus and subsequent formation of osseous tissue and the absence of radiolucency within the previous site of the enchondroma. Patients who were lost to follow-up prior to complete consolidation were considered to have “bony consolidation in progress.” In the context of the case series, recurrence was defined as recurrent clinical symptoms of pain, swelling, deformity, or a pathological fracture in conjunction with a radiographic reappearance of the lesion at the same site of previous surgical treatment.

Surgical Technique

All procedures were performed under general anesthesia and tourniquet control. One attending surgeon performed or supervised all procedures. Dorsolateral incisions directly overlying the cortical bone enclosing the enchondroma were used for metacarpal, proximal phalanx, and middle phalanx lesions. Distal phalangeal lesions were all exposed through a midline, volar incision. A beaver blade was used to cut a cortical window, and a curette was then used to remove the tumor and to help visualize the inner surface of the bone. At times, a 30-degree arthroscope was inserted to help visualize the inner cortex to ensure that the lesion was completely removed (boneoscopy). Phenol chemical cautery was used as an adjunct to curettage in 6 out of 26 (23 %) cases. Phenol was used when there were “nests” of cartilage imbedded in the intramedullary wall of cortical bone and there was a concern that the lesion could not be completely removed without creating a new fracture through the thin cortical bone. In all but 1 case, patients that presented with a pathological fracture were allowed to heal prior to surgery. One pathological fracture was stabilized during the curettage with two Kirschner wires as the fracture involved the proximal phalanx and was displaced enough that adequate reduction could not be maintained without surgical fixation. Postoperatively, patients were splinted for 3–6 weeks in the intrinsic plus position. The duration of splinting depended on the patient’s comfort. Typically, a distal or middle phalanx was splinted for 2 weeks and a metacarpal or proximal phalanx splinted for 6 weeks. Radiographs were typically obtained on the first postoperative visit, 6 weeks, and 12 weeks. For lesions that appeared to have small homogeneous, well-demarcated lucencies, with typical intralesional calcifications, follow-up usually ended between 3 and 6 months; however, for larger, more atypical lesions with concern for low-grade chondrosarcoma, patients were seen for at least 1 year and asked to return on a yearly basis.

Systematic Literature Review

In October 2013, a MEDLINE and CINHAL database search was conducted to identify studies on the treatment of hand enchondroma. The MEDLINE search query consisted of the following expression: “enchondroma*[TI] AND (hand OR Wrist OR carpus OR phalanges OR fingers OR metacarpals OR thumb) NOT Review.” Limits were applied to include English and German language articles only. The literature search included the past 25 years, beginning January 1st 1988 until October 1st 2013. The bibliographies of articles identified in the initial search were also analyzed to detect relevant studies, and eight additional studies were identified. In addition, one study indexed in Medline as a non-English study had an available English version and was included [35]. The authors’ case series was also included in the synthesis.

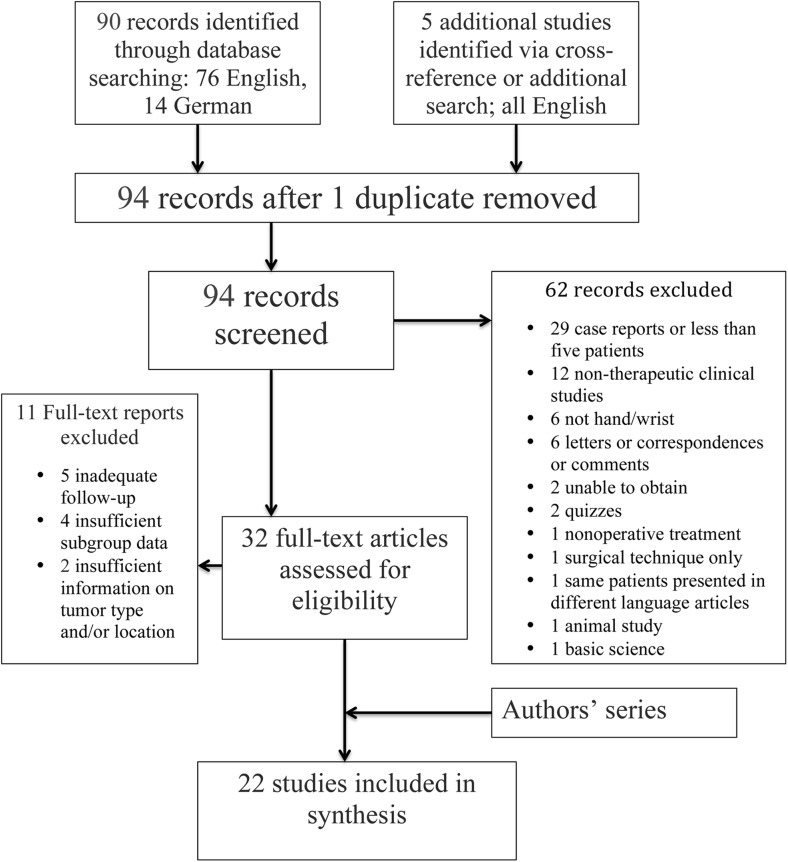

The titles and abstracts were screened, and the following additional exclusion criteria applied: (1) case reports, or case series with less than 5 patients; (2) nontherapeutic/diagnostic studies; (3) enchondromas in anatomical locations other than the hand or wrist; (4) correspondence letters or quizzes; (5) nonoperative treatment; (6) surgical technique only; (7) animal studies; and (8) basic science studies. In addition, articles that could not be obtained either electronically or in print through the authors’ institution were excluded. Secondary inclusion criteria involved the following: (1) data with at least 3 months of clinical follow-up; (2) sufficient descriptive details of the anatomical location and type of tumor to enable subgroup allocation and analysis; and (3) for studies that described more than one surgical technique, distinct subgroup data and outcomes were required to enable accurate case categorization. Figure 1 represents a flowchart that summarizes the inclusion and exclusion process. Two reviewers independently assessed each of the studies for eligibility and inclusion.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart presenting the exclusion and inclusion criteria and the number of studies assessed

Eligible studies were then categorized into four broad treatment groups that included the following: (1) curettage without subsequent augmentation, (2) curettage followed by augmentation with autograft, (3) curettage followed by augmentation with bioactive and osteoconductive materials other than autograft, and (4) curettage followed by augmentation with bone cements that provide early structural support. Patients who were treated for enchondromas in a location other than the hand or carpal bones (n = 3, 1 distal ulna, 2 metatarsal lesions) or with a method other than curettage (n = 1, trans-metacarpal amputation) were also excluded. Complications and recurrence were the main outcomes of interest and underwent separate statistical analyses because recurrence is generally thought to correlate with time, and the available follow-up time periods for the various treatment modalities were markedly different. When possible, patients with multiple enchondromatosis were excluded from complication and recurrence analyses, as these patients are expected to have a higher recurrence rate. Complications were defined as nonunion, malunion, infection, postoperative fracture, persistent pain or symptoms, postoperative hematoma requiring reoperation. Although soft tissue complications were noted within the results of the authors’ current case series, this category of complications was considered largely dependent on surgical dissection as well as postoperative rehabilitation and was not assessed during the systematic review. For the same reason, postoperative functional results such as range of motion and grip strength were not assessed.

Levels of evidence were assigned to each study in accordance with the Oxford Center for Evidence-Based Medicine’s Levels of Evidence [23]. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) checklist was used as a framework to guide this systematic review [19]. Fisher’s exact test was used for statistical analysis, and a two-tailed p value less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Case Series

Thirty-two patients met the inclusion criteria, and 24 remained after the exclusion criteria were applied. There were 5 men and 19 women, with a total of 26 histologically confirmed lesions. The mean age at surgery was 38.9 years (range 14–61). The mean follow-up was 26 months (range 3–120). Thirteen patients presented with a pathological fracture (54 %). The median time after initial presentation to surgery for 12/13 patients with pathological fractures (and available data) was 29.5 days (range 9–986 days). Two patients who developed pathological fractures elected to proceed with nonoperative treatment and close follow-up but eventually underwent surgery 481 and 986 days after fracture due to persistent pain. The mean lesion size was 14 × 10 × 8 mm (Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics and lesion characteristics of patients in the authors’ case series

| Number | Sex | Age at surgery | Presenting symptoms | Tumor location | Follow-up (months) | Complications | Radiographic findings | Tumor dimensions (length × width depth) mm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | F | 14,23 | Swelling/deformity | Right ring proximal phalanx | 108 | PIPJ contracture following second procedure | Consolidation in progress following second procedure | Missing preoperative X-rays |

| 2 | M | 25 | Pathologic fracture | Right ring distal phalanx | 3 | None | Consolidation in progress | 11 × 6 × 5 |

| 3 | F | 48 | Pain | Right index proximal phalanx | 12 | Osteophyte formation at MPJ requiring osteophyte removal | Complete consolidation | 11 × 12 × 10 |

| 4 | M | 43 | Pathologic fracture | Right ring metacarpal | 23 | None | Complete consolidation | 20 × 10b |

| 5 | F | 58 | Swelling/deformity | Right index distal phalanx |

17 | None | Complete consolidation | 3 × 3 × 3 |

| 6 | F | 46 | Swelling/deformity | Right ring middle phalanx | 64 | None | Complete consolidation | 11 × 10 × 12 |

| 7 | F | 51 | Pain | Right index metacarpal | 5 | None | Complete consolidation | 14 × 13b |

| 8 | F | 50 | Pathologic fracture | Left ring metacarpal | 8 | MPJ extension contracture requiring dorsal MPJ capsule release | Complete consolidation | 11 × 13b |

| 9 | F | 34 | Swelling/deformity | Right ring distal phalanx | 4 | None | Complete Consolidation | 12 × 9 × 8 |

| 10a | M | 35 | Pathological fracture | Right ring proximal phalanx | 6 | None | Complete consolidation | Missing preoperative X-rays |

| 11 | F | 41 | Pathological fracture | Right long metacarpal | 55 | None | Complete consolidation | 20 × 10b |

| 12 | F | 31 | Pathological fracture | Left ring proximal phalanx | 12 | None | Complete consolidation | Missing preoperative X-rays |

| 13 | M | 36 | Pathological fracture | Right ring metacarpal | 3 | None | Consolidation in progress | 13 × 9b |

| 14 | F | 61 | Pathological fracture | Right small metacarpal | 14 | None | Consolidation in progress with persistent medullary and cortical alteration in architecture | 25 × 13b |

| 15 | F | 25 | Pain | Left index proximal phalanx | 5 | None | Complete consolidation with persistent medullary and cortical alteration in architecture | 11 × 16 × 11 |

| 16 | F | 32 | Pathological fracture | Left thumb distal phalanx | 5 | None | Consolidation in progress | Missing preoperative X-rays |

| 17 | F | 15 | Incidental | Right small proximal metacarpal | 90 | None | Complete consolidation | 9 × 9b |

| Pathological fracture | Right small distal metacarpal | None | Complete consolidation | 16 × 6b | ||||

| 18 | F | 31 | Pain | Left thumb proximal phalanx | 120 | None | Complete consolidation | 11 × 9 × 8 |

| 19 | F | 47 | Pain | Left thumb distal Phalanx | 5 | None | Complete consolidation | 9 × 9 × 11 |

| 20 | F | 45 | Pathological fracture | Right ring distal phalanx | 4 | Swan-neck deformity | Complete consolidation | 5 × 6 × 6 |

| 21 | M | 51 | Pain | Left index proximal phalanx | 24 | None | Persistent medullary and cortical alteration in architecture | 25 × 12 × 12 |

| 22 | F | 45 | Pain | Right index middle phalanx | 12 | None | Persistent medullary void and consolidation in progress | 9 × 6 × 7 |

| 23 | F | 48 | Pathological fracture | Right small middle phalanx | 4 | None | Missing postoperative X-rays | Missing preoperative X-rays |

| 24 | F | 18 | Incidental | Right ring middle phalanx | 23 | None | Complete consolidation | 18 × 10 × 8 |

| Pathological fracture | Right ring metacarpal | None | Complete consolidation | 22 × 13b |

aFixed with K-wire

bUnable to obtain due to metacarpal overlap on lateral view X-rays

MPJ metacarpophalangeal joint, PIPJ proximal interphalangeal joint

One patient developed recurrence 9 years after the initial procedure, underwent repeat curettage, and subsequently developed contracture of the ring finger proximal interphalangeal joint. Other soft tissue complications consisted of a swan neck deformity and a metacarpophalangeal joint contracture. There were no refractures or nonunions. At the latest follow-up, complete radiographic consolidation was observed in 17/25 cases (68 %), consolidation in progress was observed in 4 cases (16 %), and irregular cortical and medullary changes persisted in 4 asymptomatic cases (16 %).

Systematic Review

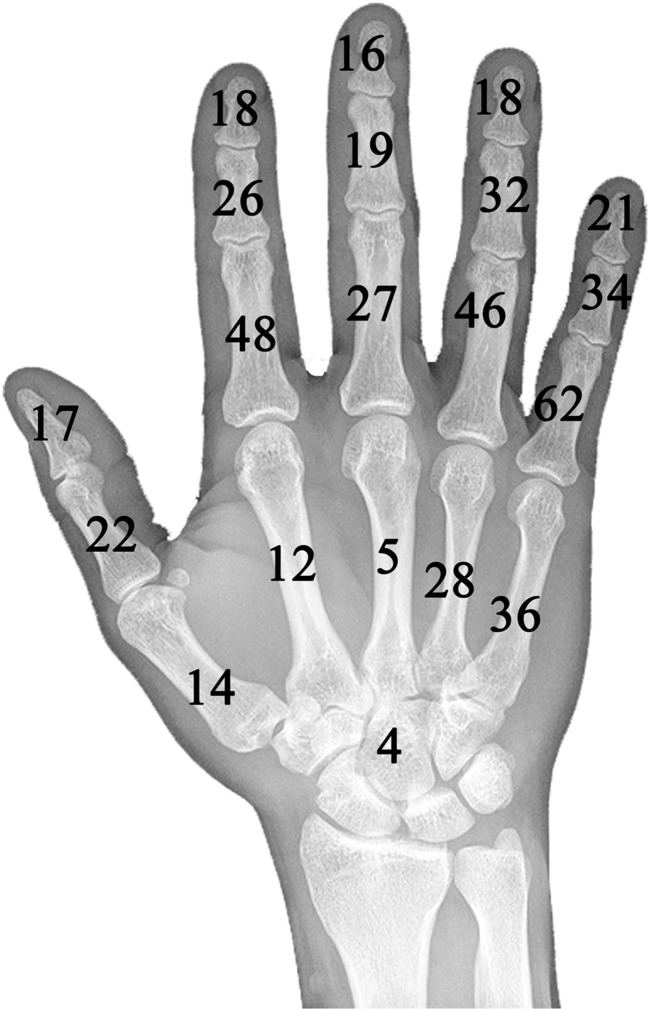

After applying the exclusion and inclusion criteria, 22 studies that incorporated a total of 591 patients and 609 lesions were selected for further analysis (Table 2). Sex and the mean age could not be determined in 42 patients. For the remaining 549 patients, there were 249 males (45 %) and 300 females (55 %). The calculated mean age for these 549 patients was 35.1 (range 6–79 years). Six patients with Ollier’s syndrome were identified. There were no patients with Maffucci’s syndrome. The distribution of the lesions in 104 cases could not be determined. The distribution of the remaining 505 lesions is depicted in Fig. 2. The number of patients and lesions in each category were as follows: (1) curettage without further filling, 254 patients, 259 lesions; (2) curettage followed by autograft augmentation, 226 patients, 232 lesions; (3) curettage followed by augmentation with osteoconductive materials other than autografts, 62 patients, 69 lesions; and (4) curettage followed by void augmentation with bone cements, 49 patients, 49 lesions. The respective, calculated mean follow-up times for each category were (1) 3.6 years (range 0.3–16) (n = 249 patients, 8 studies); (2) 8.1 years (range 0.7–22 years) (n = 184 patients, 6 studies); (3) 4.7 years (range 1.3–11.6 years) (n = 50 patients, 3 studies); and (4) 3.1 years (range 1.0–15 years) (n = 49 patients, 5 studies).

Table 2.

Basic study and patient data of the systematic review

| Year | Authors | Surgical technique | Cases | Presentation (cases) | Mean follow-up in years (range) | Assigned evidence level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1988 | Bauer et al. | C + IC cancellous autograft | 14 | 7 F, 1I, 6P | 2.9 (1.5–5.2) | 4 |

| C + freeze dried corticocancellous allograft | 19 | 8 F, 1I, 5 M, 3O, 1P | ||||

| 1989 | Kuur et al. | C+ DR, IC autograft | 15 | NA | 4.6 (1.1–9.5) | 4 |

| C + no fill | 5 | |||||

| 1990 | Tordai et al. | C + no fill | 44 | 4D, 24 F, 5I, 11P | 6.5 (3–12) | 4 |

| 1990 | Wulle | C + no fill + 70 % alcohol swab | 9 | NA | 1.1 (0.4–2.8) | 4 |

| 1991 | Hasselgren et al. | C + no fill | 28 | 7D, 16 F, 5I | 6 (0.5–16) | 4 |

| 1997 | Machens et al. | C + IC, DR or elbow autograft | 73a | 4D, 28 F, 8I, 1O, 31P | 6 (NA) | 4 |

| 5b | 5D | |||||

| 1997 | Sekiya et al. | C + no fill (endoscopic) | 9 | 2D, 6 F, 1I | 1.2 (0.6–2.1) | 4 |

| 1999 | Giles et al. | C + CO2 laser + autograft | 14 | NA | 3.0 (1.2–8.8) | 4 |

| 2000 | Joosten et al. | C+ hydroxyapatite Cement | 8 | 5D, 1 F, 2I | 1 | 4 |

| 2002 | Montero et al. | C+ DR, IC autograft | 21 | 5 F, 3I, 3P, 10P&D | 1.1 (0.7–2.0) | 4 |

| 2002 | Goto et al. | C + no fill + cortical window replacement | 18 | 2D, 10 F, 9I, 4P | 1.6 (0.5–4.9) | 3B |

| C + no fill, no cortical window replacement | 6 | |||||

| 2002 | Bickels et al. | C + burr + PMMA cemented internal fixation | 13 | 8 F, 5P | 6.1 (2.1–15.3) | 4 |

| 2004 | Yercan et al. | C + IC autograft | 61 | 22D, 39 F, 15I | 13.5 (10–22) | 4 |

| C+ dehydrated cancellous allograft | 15 | 7.4 (6–11) | ||||

| 2004 | Gaulke et al. | C ± burr + cancellous autograft; 1 case C + protein composite | 21 | 2D, 9 F, 5I, 5P | 9 (2–18) | 4 |

| 2005 | Gaasbeek et al. | C ± burr + antibiotic impregnated plaster of Paris tablets | 17 | 9D, 8 F | 4.4 (1.3–11.6) | 4 |

| 2006 | Yasuda et al. | C + calcium phosphate cement | 10 | 5 F, 5O | 3.4 (2.5–5.3) | 4 |

| 2009 | Schaller et al. | C + no fill | 8 | 7 F, 7I, 2P | 5.7 (3.5–9.0) | 4 |

| C + IC autograft | 8 | 4.1 (2.4–5.4) | ||||

| 2010 | Werdin et al. | C + no fill | 106 | NA | 2.8 (1.0–6.2) | 4 |

| 2012 | Choy et al. | C + calcium sulfate pellets | 18 | 1 F, 14P, 3P&D | 2.7 (1.5–4.0) | 4 |

| 2012 | Kim et al. | C + calcium phosphate cement | 10 | 2 F, 8O | 1.6 (1.0–2.6) | 4 |

| 2013 | Lin et al. | C + calcium sulfate cement | 8 | 8 F | 1.6 (1.0–3.0) | 4 |

| 2014 | Current study | C + no fill ± phenol swab | 26 | 5D, 13 F, 2I, 6P | 2.3 (0.3–10) | 4 |

C curettage, D deformity or swelling, DR distal radius, f female, F pathological fracture, I incidental finding, IC iliac crest, m male, M multiple enchondramatosis, NA information not available or could not be determined, O other or nonspecified presentation, P pain, PMMA polymethyl methacrylate

aMono-ostotic lesions

bPoly-ostotic lesions

Fig. 2.

The distribution of 505 hand enchondromas is presented. There is a predilection towards the proximal phalanges and the ulnar side of the hand. Four cases occurred in the carpal bones

Complications, excluding recurrence, were assessed in 21/22 studies and occurred at an incidence of 0.7 % following curettage alone; 3.5 % in the autograft group; 0 % in the group that used bioactive/osteoconductive materials; and 2.0 % in the group treated with cement. One third of all complications in the autograft group (5/15) were related to problems at the iliac crest donor site, including persistent pain and infection. Complications are described in Table 3 and Appendix 1.

Table 3.

Complications, excluding recurrence, stratified by treatment category

| Complication | No void filling (n = 148a) | Void filling with autograft (n = 226) | Void filling with bioactive and osteoconductive materials other than autograft (n = 62) | Void filling with bone cement (n = 49) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Infection | 0 | 5 | 0 | 0 |

| 2. Nonunion | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 3. Malunion | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 4. Persistent pain/symptoms | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| 5. Refracture | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 6. Reoperation for hematoma | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Total (%) | 1 (0.7 %) | 8 (3.5 %) | 0 (0 %) | 1 (2.0 %) |

n number of patients

aThe study by Werdin et al. was excluded from this analysis as no clinical complications were presented

Table 4.

Details of all postoperative complications, including recurrence, stratified by treatment category

| Treatment category | Authors | Patients | Complications and recurrence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Curettage without void filling | Kuur et al. | 5 | None |

| Tordai et al. | 42 | 1 recurrence | |

| Wulle | 9 | 1 patient had persistent symptoms and underwent repeat surgery to rule out recurrence. No recurrence was found | |

| Hasselgren et al. | 28 | None | |

| Sekiya et al. | 9 | None | |

| Goto et al. | 23 | None | |

| Schaller et al. | 8 | None | |

| Werdin et al.a | 106 | 3 patients had radiographic recurrence | |

| Current study | 24 | 1 recurrence 9 years postoperatively. | |

| Curettage followed by void filling with autograft | Bauer et al.b | 14 | 1 patient developed an infection at the IC donor site; 1 patient complained of persistent pain at the IC site. |

| Kuur et al. | 15 | None | |

| Machens et al.d | 78 | 2 infections; 1 hematoma at the IC graft site requiring surgery; 1 RSD; 1 recurrence. | |

| Giles et al. | 8 | None | |

| Montero et al. | 21 | 1 patient experienced recurrence 6 years after the initial surgery | |

| Yercan et al. | 61 | 2 recurrences; 2 infections at IC graft site treated with oral antibiotics | |

| Gaulke et al. | 21 | 3 patients experienced recurrence 11–17 years postoperatively | |

| Schaller et al. | 8 | None | |

| Curettage followed by void filling with bioactive and osteoconductive materials other than autograft | Bauer et al. | 12 | None |

| Yercan et al.c | 15 | None | |

| Gaasbeek et al. | 17 | None | |

| Choy et al. | 18 | None | |

| Curettage followed by void filling with bone cement | Joosten et al. | 8 | None |

| Bickels et al. | 13 | None | |

| Yasuda et al. | 10 | 1 patient developed malunion that required corrective osteotomy | |

| Kim et al. | 10 | None | |

| Lin et al. | 8 | None |

aOnly radiographic data and no clinical results provided

bTwo recurrences initially treated at other institution excluded from analysis

cOne patient with multiple enchondromatosis experienced malignant degeneration 18 months postoperatively and underwent ray amputation excluded from analysis

dSix patients had primary arthrodesis or amputations secondary to postoperative soft tissue contractures or restrictions and were excluded from the analysis

IC iliac crest, MCPJ metacarpophalangeal joint, PIPJ proximal interphalangeal joint, RSD reflex sympathetic dystrophy

Recurrence was assessed in all 22 studies and occurred at an incidence of 2.0 % following curettage alone, 3.2 % in the autograft group, 0 % in the group that used other osteoconductive materials, and 0 % in the group treated with cement. None of the patients with recurrence had a history of Ollier’s disease. There were no statistical differences when complication rates or recurrence were compared, p > 0.05 (Appendix 2).

Table 5.

Statistical analyses of recurrence and complication rates using Fisher’s exact test

| Complication ratesa | P value |

| Group 1 vs group 2 | 0.094 |

| Group 1 vs group 3 | 1.000 |

| Group 1 vs group 4 | 0.437 |

| Group 2 vs group 3 | 0.209 |

| Group 2 vs group 4 | 1.000 |

| Group 3 vs group 4 | 0.441 |

| Recurrence ratesb | P value |

| Group 1 vs group 2 | 1.000 |

| Group 1 vs group 3 | 0.587 |

| Group 1 vs group 4 | 1.000 |

| Group 2 vs group 3 | 0.353 |

| Group 2 vs group 4 | 0.359 |

| Group 3 vs group 4 | 1.000 |

Group 1: curettage followed by no void augmentation; group 2: curettage followed by augmentation with autograft; group 3: curettage followed by augmentation with bioactive or osteoconductive materials other than autografts; group 4: curettage followed by augmentation with cements

a N, group 1 = 148

b N, group 1 = 254

Discussion

Debate persists regarding the efficacy of various methods of postcurettage void augmentation during the surgical treatment of hand enchondroma. The purpose of this study is to show that curettage alone is safe and reliable as compared to curettage followed by void augmentation based on the authors’ outcomes and a systematic review of the literature.

The presented case series spanned a 25-year period. During this time, encouraging results were consistently observed when hand enchondromas were treated by curettage without void augmentation. Despite various clinical presentations and various tumor sizes, with a maximum lesion size measuring 25 × 12 × 12 mm, there were no postoperative fractures, nonunions, or infections. Complete radiographic consolidation of the curetted lesion was usually noted 4 months postoperatively. In some instances, persistent cortical and medullary architectural changes were a concern for potential recurrence or malignant transformation. However, these concerns did not become clinical problems for our patients.

It should be noted that across all studies, favorable outcomes of hand function are common, while complications are uncommon [1, 2, 6, 9, 11, 12, 14, 21, 30, 34]. Although soft tissue complications were not analyzed in this study, contractures leading to postoperative functional restrictions could be a major source of patient distress following enchondroma surgery [18]. Most complications that developed in our series were related to soft tissue compromise and included two small joint contractures and a swan neck deformity in one case. This category of complications, however, is thought to be more dependent on the process of surgical dissection and postoperative rehabilitation, rather than the process of void management. The results of the systematic review did not demonstrate any statistical differences in complication rates between the various forms of void management. Each form of treatment, however, possesses a unique set of documented and theoretic complications. When considering the use of autograft, one third of complications were related to donor site morbidity, including pain and infection at the iliac crest donor site. In light of these findings, it would be advisable to proceed cautiously if planning to use iliac crest autograft for augmentation. Allograft is more costly than other options and concerns persist about infection of the allograft despite improvements in screening techniques [22], although there were no such complications described in this systematic review. The theoretic benefits of structural support fillers, such as various forms of bone cement, include their ability to limit the period of immobilization and postoperative recovery and enable quick return to function. Pianta et al. studied the biomechanical advantage of void augmentation with calcium phosphate cement in an enchondroma model [24]. The authors found that although cement augmentation provided significantly increased strength to failure as compared to curettage alone, it afforded less strength in comparison to native cortical bone. The authors also noted no differences in peak load when curettage alone was compared to curettage followed by augmentation with bovine matrix, a surrogate for cancellous allograft. Although cement augmentation affords additional strength to the curetted phalanx or metacarpal, it may not be clinically required given the restricted weight bearing status of patients during postoperative recovery. In theory, cement extravasation into nearby fractures or soft tissues could be a concern, particularly if the cement solidifies over the flexor or extensor tendons. Although these complications were not reported in any of the studies assessed in the systematic review, authors who have used bone cement warn about cement leakage [2, 34]. Prolonged preparation, administration, toxicity, setting time, and cost are additional drawbacks that must be considered when planning to fill voids with bone cement. Importantly, not a single postoperative fracture was documented in the 609 lesions analyzed, most of which were treated by curettage without augmentation. This point is particularly useful for guiding future enchondroma treatment, as the rationale for augmentation has been based, in large part, on improving structural integrity and decreasing postoperative fracture rates.

The recurrence rate was found to be highest in the autograft augmentation group, 3.5 %, and this was followed by the group with no augmentation, 2.0 %. The mean respective follow-up times, however, were 8.1 and 3.6 years. Because enchondroma recurrence is generally thought to be temporally associated, without adequate control for the duration of follow-up, it is not possible to conclude whether any treatment options increase or reduce susceptibility to recurrence.

One of the major limitations in the literature review is that not all outcome data were compared from all studies in a uniform manner and we were unable to analyze radiographic outcomes. Second, although it would have been useful to analyze the influences of surgical adjuncts on outcomes (alcohol, phenol, laser [10], thermal necrosis via bone cement, etc.), this aspect was not investigated due to the limited availability of data. Similarly, a discussion of lesion size could not be conducted secondary to the lack of data within the existing literature. It should be noted that traditionally, surgeons have preferred to wait for pathological fractures to heal prior to proceeding with operative treatment secondary to the belief that complication rates would be higher with immediate curettage. In recent years, however, there has been a trend toward immediate one-stage treatment, as some authors have demonstrated encouraging results based on case series [17]. During the initial stages of this study, we attempted to address the question of whether any differences in patient outcomes existed with one versus two-stage treatment protocols. However, the overwhelming majority of studies reviewed used a two-stage approach, and this question had to be aborted. This question requires more definitive clinical study.

Despite the limitations, several conclusions could be drawn from this study. First, all studies but one were assigned an evidence level of 4, which highlights the limits of current evidence. The results of this study may be used to optimize the design of prospective comparative studies that investigate void management as it relates to the duration of postoperative immobilization, and the impact of surgical adjuncts on recurrence, while controlling for lesion size, and location. Second, postoperative fractures following curettage without augmentation are uncommon, as this complication was not documented in any study. The outcomes of this investigation support the notion that simple curettage without the use of augmentation does not lead to increased complication rates. Consequently, simple curettage is an effective, low-morbidity, and inexpensive option for the treatment of most hand enchondromas.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Faith Kifer for her assistance with medical record acquisition.

Conflict of Interest

Abdo Bachoura declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Ian S. Rice declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Andrew R. Lubahn declares that he has no conflict of interest.

John D. Lubahn declares that he has no conflict of interest.

Statement of Human and Animal Rights

The research procedures in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000.

Statement of Informed Consent

Institutional review board approval was acquired for this study; however, patient consent was waived due to the retrospective nature of the study.

Appendix

Appendix 1

Appendix 2

References

- 1.Bauer RD, Lewis MM, Posner MA. Treatment of enchondromas of the hand with allograft bone. J Hand Surg [Am] 1988;13:908–16. doi: 10.1016/0363-5023(88)90269-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bickels J, Wittig JC, Kollender Y, et al. Enchondromas of the hand: treatment with curettage and cemented internal fixation. J Hand Surg [Am] 2002;27:870–5. doi: 10.1053/jhsu.2002.34369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Choy W, Kim KJ, Lee SK, et al. Treatment for hand enchondroma with curettage and calcium sulfate pellet (OsteoSet®) grafting. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol. 2012;22:295–9. doi: 10.1007/s00590-011-0842-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Culver JE, Jr., Sweet DE, McCue FC. Chondrosarcoma of the hand arising from a pre-existent benign solitary enchondroma. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1975:128–131. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Emecheta IE, Bernhards J, Berger A. Carpal enchondroma. J Hand Surg (Br) 1997;22:817–9. doi: 10.1016/S0266-7681(97)80457-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Figl M, Leixnering M. Retrospective review of outcome after surgical treatment of enchondromas in the hand. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2009;129:729–34. doi: 10.1007/s00402-008-0715-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaasbeek RD, Rijnberg WJ, van Loon CJ, et al. No local recurrence of enchondroma after curettage and plaster filling. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2005;125:42–5. doi: 10.1007/s00402-004-0747-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gaulke R. The distribution of solitary enchondromata at the hand. J Hand Surg (Br) 2002;27:444–5. doi: 10.1054/jhsb.2002.0826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gaulke R, Suppelna G. Solitary enchondroma at the hand. Long-term follow-up study after operative treatment. J Hand Surg (Br) 2004;29:64–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsb.2003.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giles DW, Miller SJ, Rayan GM. Adjunctive treatment of enchondromas with CO2 laser. Lasers Surg Med. 1999;24:187–93. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-9101(1999)24:3<187::AID-LSM3>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goto T, Yokokura S, Kawano H, et al. Simple curettage without bone grafting for enchondromata of the hand: with special reference to replacement of the cortical window. J Hand Surg (Br) 2002;27:446–51. doi: 10.1054/jhsb.2002.0843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hasselgren G, Forssblad P, Tornvall A. Bone grafting unnecessary in the treatment of enchondromas in the hand. J Hand Surg [Am] 1991;16:139–42. doi: 10.1016/S0363-5023(10)80031-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jewusiak EM, Spence KF, Sell KW. Solitary benign enchondroma of the long bones of the hand. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1971;53:1587–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joosten U, Joist A, Frebel T, et al. The use of an in situ curing hydroxyapatite cement as an alternative to bone graft following removal of enchondroma of the hand. J Hand Surg (Br) 2000;25:288–91. doi: 10.1054/jhsb.2000.0383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim JK, Kim NK. Curettage and calcium phosphate bone cement injection for the treatment of enchondroma of the finger. Hand Surg. 2012;17:65–70. doi: 10.1142/S0218810412500104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kuur E, Hansen SL, Lindequist S. Treatment of solitary enchondromas in fingers. J Hand Surg (Br) 1989;14:109–12. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681(89)90029-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lin SY, Huang PJ, Huang HT, et al. An alternative technique for the management of phalangeal enchondromas with pathologic fractures. J Hand Surg [Am] 2013;38:104–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.08.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Machens HG, Brenner P, Wienbergen H, et al. Enchondroma of the hand. Clinical evaluation study of diagnosis, surgery and functional outcome. Unfallchirurg. 1997;100:711–4. doi: 10.1007/s001130050181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6:e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Montero LM, Ikuta Y, Ishida O, et al. Enchondroma in the hand retrospective study–recurrence cases. Hand Surg. 2002;7:7–10. doi: 10.1142/S0218810402000893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Morii T, Mochizuki K, Tajima T, et al. Treatment outcome of enchondroma by simple curettage without augmentation. J Orthop Sci. 2010;15:112–7. doi: 10.1007/s00776-009-1419-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mroz TE, Joyce MJ, Steinmetz MP, et al. Musculoskeletal allograft risks and recalls in the United States. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2008;16:559–65. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200810000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Patsopoulos NA, Analatos AA, Ioannidis JP. Relative citation impact of various study designs in the health sciences. JAMA. 2005;293:2362–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.19.2362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pianta TJ, Baldwin PS, Obopilwe E, et al. A biomechanical analysis of treatment options for enchondromas of the hand. Hand. 2013;8:86–91. doi: 10.1007/s11552-012-9476-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Redfern DR, Forester AJ, Evans MJ, et al. Enchondroma of the scaphoid. J Hand Surg (Br) 1997;22:235–6. doi: 10.1016/S0266-7681(97)80071-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sassoon AA, Fitz-Gibbon PD, Harmsen WS, et al. Enchondromas of the hand: factors affecting recurrence, healing, motion, and malignant transformation. J Hand Surg [Am] 2012;37:1229–34. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schaller P, Baer W. Operative treatment of enchondromas of the hand: is cancellous bone grafting necessary? Scand J Plast Reconstr Surg Hand Surg. 2009;43:279–85. doi: 10.3109/02844310902891570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sekiya I, Matsui N, Otsuka T, et al. The treatment of enchondromas in the hand by endoscopic curettage without bone grafting. J Hand Surg (Br) 1997;22:230–4. doi: 10.1016/S0266-7681(97)80070-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Takigawa K. Chondroma of the bones of the hand. A review of 110 cases. J Bone Joint Surg. 1971;53:1591–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tordai P, Hoglund M, Lugnegard H. Is the treatment of enchondroma in the hand by simple curettage a rewarding method? J Hand Surg (Br) 1990;15:331–4. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681(90)90013-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Werdin F, Jaminet P, Rennekampff HO, et al. Does additive spongiosaplasty improve outcome after surgical therapy for solitary enchondroma in the hand? Handchir Mikrochir Plast Chir. 2010;42:299–302. doi: 10.1055/s-0030-1254087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wulle C. On the treatment of enchondroma. J Hand Surg (Br) 1990;15:320–30. doi: 10.1016/0266-7681(90)90012-S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yanagawa T, Watanabe H, Shinozaki T, et al. Curettage of benign bone tumors without grafts gives sufficient bone strength. Acta Orthop. 2009;80:9–13. doi: 10.1080/17453670902804604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yasuda M, Masada K, Takeuchi E. Treatment of enchondroma of the hand with injectable calcium phosphate bone cement. J Hand Surg [Am] 2006;31:98–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2005.08.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Yercan H, Ozalp T, Coskunol E, et al. Long-term results of autograft and allograft applications in hand enchondromas. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc. 2004;38:337–42. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]