Abstract

Background

The prevalence and determinants of dyslipidemia patterns among Hispanics/Latinos are not well known.

Methods

Lipid and lipoprotein data were used from the Hispanic Community Health Study / Study of Latinos -- a population-based cohort of 16,415 US Hispanic/Latinos ages 18–74. National Cholesterol Education Program cutoffs were employed. Differences in demographics, lifestyle factors, biological and acculturation characteristics were compared among those with and without dyslipidemia.

Results

Mean age was 41.1 years and 47.9% were male. The overall prevalence of any dyslipidemia was 65.0%. The prevalence of elevated LDL-C was 36.0% and highest among Cubans (44.5%; p<0.001). Low HDL-C was present in 41.4% and did not significantly differ across Hispanic background groups (p=0.09). High triglycerides were seen in 14.8% of Hispanics/Latinos, most commonly among Central Americans (18.3%; p<0.001). Elevated non-HDL-C was seen in 34.7% with the highest prevalence among Cubans (43.3%; p<0.001). Dominicans consistently had a lower prevalence of most types of dyslipidemia. In multivariate analyses, the presence of any dyslipidemia was associated with increasing age, body mass index and low physical activity. Older age, female gender, diabetes, low physical activity, and alcohol use were associated with specific dyslipidemia types. Spanish-language preference and lower educational status were associated with higher dyslipidemia prevalence.

Conclusion

Dyslipidemia is highly prevalent among US Hispanics/Latinos; Cubans seem particularly at risk. Determinants of dyslipidemia varied across Hispanic backgrounds with socioeconomic status and acculturation having a significant effect on dyslipidemia prevalence. This information can help guide public health measures to prevent disparities among the US Hispanic/Latino population.

Keywords: Lipids, Dyslipidemia, Hispanics, Race-ethnic, Epidemiology

Cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of death among Hispanics/Latinos in the United States (US),1 yet Hispanics/Latinos have been underrepresented in studies of cardiovascular disease risk factors, especially lipids, as well as clinical intervention trials.2 In particular, determinants and prevalence estimates of dyslipidemia among Hispanics/Latinos are not well known. Hispanic/Latino cohorts in prior studies have been relatively small, without appropriate representation of Hispanic/Latino background groups, lacked analysis by Hispanic/Latino background groups, and were not representative of / generalizable to the total Hispanic/Latino population.3–5 Furthermore, the full complement of plasma lipid and lipoprotein components were not examined in prior studies that only used total cholesterol (TC) or low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) levels to define dyslipidemia.

The Hispanic Community Health Study / Study of Latinos (HCHS-SOL) is the largest and most comprehensive study of US Hispanic/Latino adults conducted to date.6 HCHS-SOL is multi-centered and utilized a sampling design that ensured enrollment from all the various Hispanic national/ethnic background groups7 including a full complement of plasma lipids and lipoproteins measurements.

The current analyses examined the prevalence of each dyslipidemia type among the HCHS-SOL target population; evaluated whether any of the above prevalence estimates differed by Hispanic background group; and compared differences in demographic and lifestyle factors, biological and cultural characteristics, acculturation and socioeconomic factors between those with normal and abnormal lipid and lipoprotein components.

Methods

The HCHS/SOL is a population-based study designed to examine risk and protective factors for chronic diseases and to quantify morbidity and mortality prospectively. Details of the sampling methods and design have been published.6, 7 The HCHS/SOL examined 16,415 self-identified Hispanic/Latino persons (9,835 women and 6,580 men) aged 18–74 years at the time of screening, recruited from selected households in 4 US communities (Bronx, New York; Chicago, Illinois; Miami, Florida; San Diego, California) using a stratified 2-stage area probability sample design. Census block groups were randomly selected in the defined community areas of each field center, and households were randomly selected in each sampled block group. Sampling weights were established based on the probably of selection, adjustment for non-response, trimming to handle extreme values of the weights, calibration to the known population distribution, and normalized to the entire HCHS/SOL target population. The HCHS/SOL included participants from Cuban, Dominican, Mexican, Puerto Rican, Central American, and South American backgrounds (according to self-reported national/ethnic heritage). All HCHS-SOL participants with lipid components analyzed at baseline (n = 16,207) were included in this analysis. This study was approved by the local institutional review board at each of the field centers and all participants gave informed patient consent prior to enrollment.

Lipid variables

Blood lipids and lipoproteins were measured on samples obtained after an overnight fast. Specimens were stored at −20°C and shipped we ekly to the Lipoprotein Analytical Laboratory at the HCHS/SOL Central Lab at the University of Minnesota Medical Center. This laboratory participates in the Lipid Standardization Program of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Serum TC was measured using a cholesterol oxidase enzymatic method, triglyceride (TG) and high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL-C) levels were measured with a direct magnesium/dextran sulfate method. TG levels were measured in EDTA plasma with the use of TG GB reagent (Roche Diagnostics) on a Roche centrifugal analyzer. LDL-C was calculated using the Friedewald equation.8 Non-HDL-C was calculated by subtracting the HDL-C level from TC. Different patterns of dyslipidemia were defined based on National Cholesterol Education Program / Adult Treatment Panel III (NCEP/ATP III) guidelines as follows: LDL-C > 130 mg/dl, TG > 200 mg/dl, non-HDL-C > 160 mg/dl, TC > 240 mg/dl, and low HDL-C (< 40 mg/dl for men and < 50 mg/dl for women)9, 10 Mixed dyslipidemia was defined by the presence of both elevated TG levels and low HDL-C, reflecting an increased cardiovascular risk irrespective of LDL-C levels.11, 12 ‘Any dyslipidemia’ was a variable reflective of having one or more of any of these dyslipidemia patterns.

Demographic and Clinical variables

Demographic questionnaires and medical history form were administered by trained and certified staff. Trained and certified clinic staff obtained blood samples and anthropometric and blood pressure measurements. Medication use was obtained using a questionnaire. Additionally, an inventory of both medications and supplements used during the last four weeks were also reviewed and coded. Alcohol use was captured as data on lifetime use, current use, and former use of alcohol. Physical activity was based on the commonly used Global Physical Activity Questionnaire (GPAQ) which captures self-report of low, moderate, and high energy expenditure activities both at work and during leisure time. Diabetes was defined based on American Diabetes Association definition13 using one or more of the following criteria: fasting serum glucose ≥126 mg/dl; oral glucose tolerance test ≥200 mg/dl; self-reported diabetes, A1C percentages ≥6.5 or taking anti-diabetic medication or insulin. Height was measured to the nearest 0.1 cm and weight was measured to the nearest 0.1 kilogram with the use of a balanced scale. Body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. After a 5-minute rest, blood pressure was measured three times at one-minute intervals using an automated oscillometric device in a seated position with the back and arm supported.14 All available blood pressure measurements were averaged. Ninety-nine percent of participants had all three measures. Hypertension was defined as a systolic blood pressure of 140 mmHg or higher, diastolic blood pressure of 90 mmHg or higher or on antihypertensive treatment.

Socioeconomic and Acculturation assessment

Socioeconomic position was assessed using years of educational attainment defined as highest degree or level of school completed and household income level, each classified into groups (less than high school; completed high school or high school equivalent; and attainment of education beyond high school) and (<$20,000; $20,000 to $39,999; $40,000 to $75,000 and >$75,000) respectively. Acculturation was defined using multiple proxy indicators, including nativity, duration of residence in the US, and language preference (English vs. Spanish). Greater years of residence in the US and English-language preference indicating higher levels of acculturation.

Statistical analysis

Demographic factors, anthropometric measurements, lifestyle factors, and biological profiles were compared in those with abnormal vs. normal lipid components. Continuous variables were compared using regression analysis for sample survey data and categorical variables were compared using Rao-Scott chi-square. Associations across Hispanic background groups for each dyslipidemia pattern was tested using Rao-Scott chi-square15 and regression analyses for sample survey for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Chi-square tests were used to examine whether the prevalence of each dyslipidemia pattern varied significantly across categories of SES or acculturation. Multivariate logistic regression analyses were conducted with all of the dyslipidemia correlates entered into the model simultaneously, so that the unique influence of each given correlate could be examined. All analyses were conducted using SAS survey procedure (SAS 9.3) and were weighted to adjust for sampling probability and non-response, in accordance with guidelines suggested by the HCHS-SOL Steering and Data Analysis Committees to make the estimates applicable to the target population from which the HCHS/SOL sample was drawn. In supplemental analysis, we examined TC/HDL-C and LDL-C/HDL-C ratios as continuous variables and as binary variables using established abnormal cutoffs of ≥3.5 and ≤0.4, respectively.

Results

Description of the target population

Overall, diabetes was prevalent in almost 15% of the target population while obesity prevalence approached 40%. Over half were current alcohol drinkers and about one-fifth were current smokers. Mean LDL-C levels were 119.7 mg/dl, TG 133.4 mg/dl, TC 194.3 mg/dl, and HDL-C 48.5 mg/dl; all within normal limits. Only 9.2% of the population was on lipid-lowering drugs.

Dyslipidemia in the target population and across Hispanic background groups

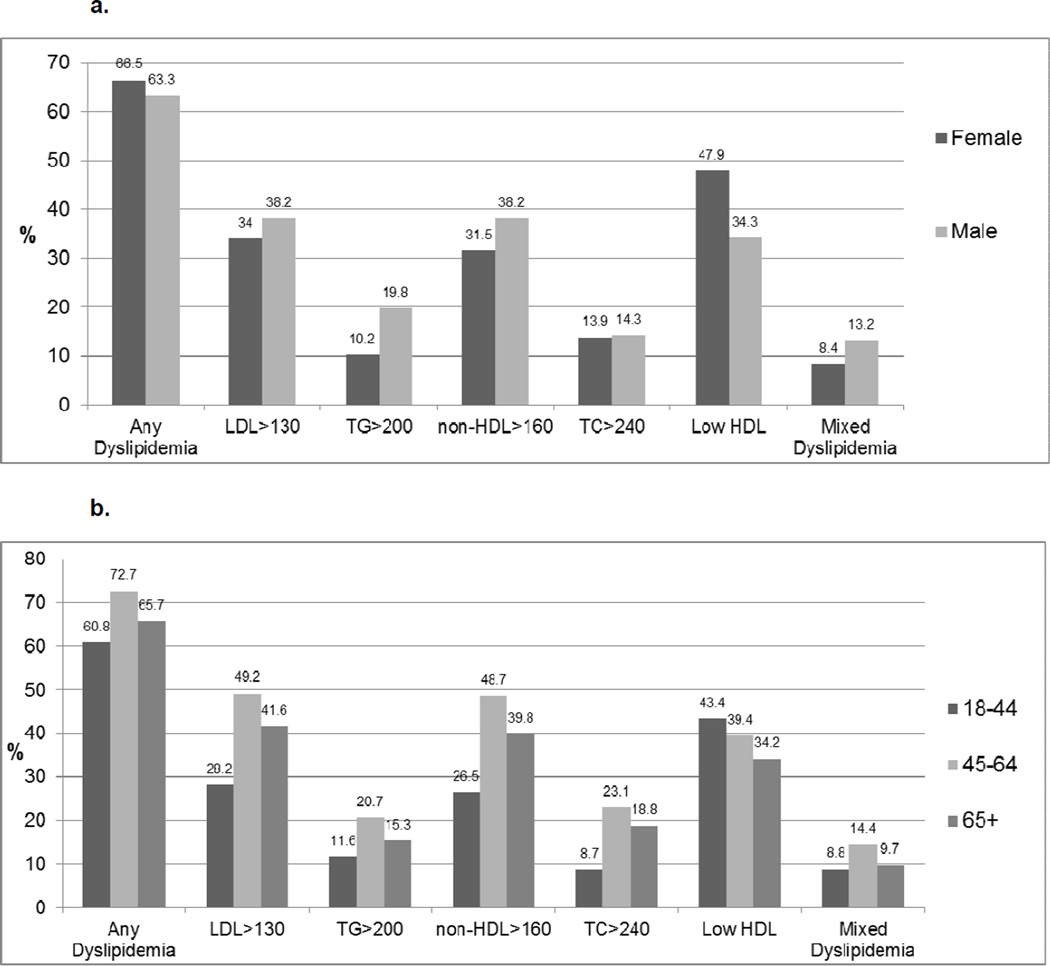

Almost two-thirds of Hispanics/Latinos had some form of dyslipidemia. Those with any dyslipidemia were significantly older, more likely to be female, more likely to have hypertension and diabetes, more likely to be obese and have low levels of physical activity and were less likely to drink any alcohol. (Table 1) Overall a slightly higher but significant proportion of women had any dyslipidemia compared to men (p<0.01). However, the distribution of specific dyslipidemia patterns varied by gender. Hispanic/Latino women had a particularly higher prevalence of low HDL-C compared to men (p<0.01); whereas Hispanic men had a higher prevalence of high LDL-C, high TG, high non-HDL-C levels, and mixed dyslipidemia compared to women (all p<0.01). In general, the various patterns of dyslipidemia were consistently less prevalent among the younger age group, then peaked in the 45–54 year age group and declined somewhat in the 65+ age group. In contrast, low HDL-C was most prevalent among younger Hispanics/Latinos compared to the other age groups (all p<0.01). (Figures 1a, 1b)

Table 1.

Descriptive Characteristics For All Hispanics And For Those With and Without Any Dyslipidemia*

| All | Any Dyslipidemia ** | No Dyslipidemia | P valueŦ | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N=16,415 | % | N=10,944 | % | N=5,304 | % | ||

| Mean age (years) | 41.1 | 42.7 | 38.1 | <0.001 | |||

| Female | 9,835 | 52.1% | 6,671 | 53.5% | 3,069 | 50.0% | 0.005 |

| Hypertension | 4,466 | 21.8% | 3,148 | 24.2% | 1,273 | 17.4% | <0.001 |

| Diabetes | 7,717 | 41.1% | 5,714 | 47.0% | 1,983 | 31.2% | <0.001 |

| Mean BMI | 29.4 | 30.3 | 27.6 | <0.001 | |||

| BMI categories | <0.001 | ||||||

| <25 | 3,320 | 23.2% | 1,636 | 16.1% | 1,643 | 36.2% | |

| 25–29.9 | 6,115 | 37.2% | 4,145 | 38.0% | 1,911 | 35.8% | |

| 30+ | 6,909 | 39.6% | 5,126 | 45.9% | 1,727 | 28.0% | |

| Waist Circumference (cm) | 97.4 | 99.8 | 93.0 | ||||

| Low Physical Activity | 9,675 | 55.5% | 6,631 | 58.3% | 2,948 | 50.1% | <0.001 |

| Current Alcohol | 7,750 | 51.7% | 4,969 | 49.3% | 2,706 | 56.1% | <0.001 |

| Current Smoking | 3,166 | 21.4% | 2,151 | 21.5% | 971 | 20.9% | 0.56 |

| Metabolic Syndrome | 3,846 | 23.4% | 3,602 | 34.2% | 242 | 4.3% | <0.001 |

All descriptive analyses use weighted frequencies and percentages

Defined as any of the following: LDL >=130, TG >=200, non-HDL >=160, TC >=240, Female and HDL < 50, Male and HDL <40, or Mixed dyslipidemia

Comparing Any Dyslipidemia vs. No Dyslipidemia

Figure 1.

In Table 2, the prevalence of any dyslipidemia was lowest among Dominicans and highest among Central Americans and Cubans. Elevated LDL-C was prevalent in over one-third of all Hispanics/Latinos, and highest among Cubans. Low HDL-C was present in 41% of the population overall; Puerto Ricans had the highest prevalence of low HDL-C dyslipidemia but not significantly different from other groups. High TGs were seen in 15% overall, most commonly among Central Americans. Elevated non-HDL-C was present in over one-third of the sample, with rates significantly higher among Cubans compared to all other groups. Prevalence rates of all four types of dyslipidemia were consistently highest among Cubans and lowest among Dominicans.

Table 2.

Prevalence Rates of Dyslipidemia Patterns among All Hispanics and Across Background Group*

| All Hispanics |

Dominican | Central American |

Cuban | Mexican | Puerto- Rican |

South American |

P- value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any Dyslipidemia** | 10,944 (65.0) | 872 (57.7) | 1,213 (68.8) | 1,690 (69.8) | 4,392 (64.8) | 1,709 (63.6) | 697 (64.7) | <0.001 |

| Total Cholesterol | 2,700 (14.1) | 208 (10.8) | 311 (16.4) | 540 (19.6) | 1,038 (13.1) | 336 (10.8) | 195 (16.6) | <0.001 |

| High LDL-C | 6,237 (36.0) | 540 (31.6) | 666 (37.8) | 1,120 (44.5) | 2,421 (33.9) | 864 (32.5) | 434 (39.8) | <0.001 |

| High TG | 2,620 (14.8) | 119 (7.6) | 342 (18.3) | 450 (17.4) | 1,094 (15.8) | 364 (13.3) | 175 (15.1) | <0.001 |

| Low HDL-C | 6,769 (41.4) | 523 (38.4) | 779 (43.5) | 966 (40.5) | 2,712 (41.9) | 1,144 (43.7) | 403 (37.0) | 0.09 |

| High non-HDL-C | 6,186 (34.7) | 480 (27.1) | 713 (37.0) | 1,108 (43.3) | 2,424 (33.5) | 838 (31.2) | 432 (38.2) | <0.001 |

| Mixed Dyslipidemia | 1,871 (10.7) | 83 (5.4) | 240 (12.7) | 319 (11.9) | 787 (11.6) | 261 (10.1) | 122 (10.2) | <0.001 |

All descriptive analyses use weighted frequencies and percentages

Defined as any of the following: LDL >=130, TG >=200, non-HDL >=160, TC >=240, Female and HDL < 50, Male and HDL <40, or Mixed dyslipidemia

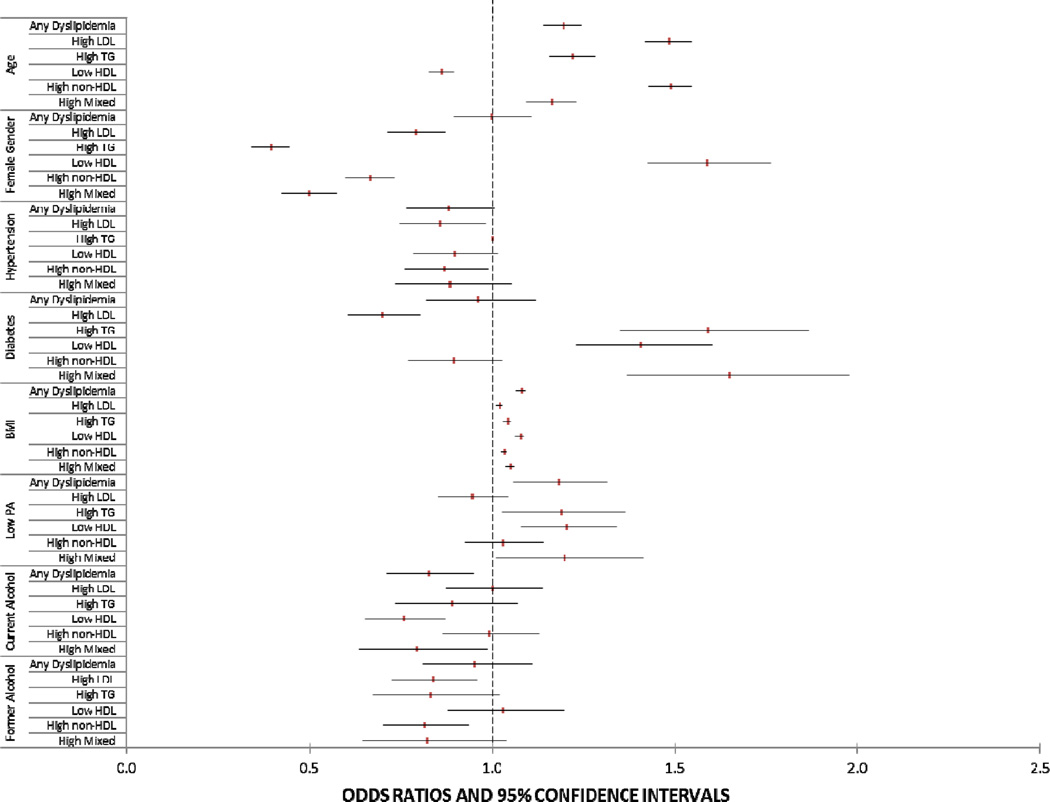

Figure 2 examines factors independently associated with some form of dyslipidemia. Overall, increasing age, female gender, higher BMI, low physical activity were all associated with Hispanics/Latinos having some form of dyslipidemia, while current alcohol use was associated with a lower odds of having any dyslipidemia. Higher age was associated with a significantly lower prevalence of low HDL but a higher prevalence of other dyslipidemia types. Female gender was associated with higher prevalence of low HDL-C but a lower prevalence of elevated TGs, non-HDL-C or LDL-C. Those with low prevalence of dyslipidemia patterns tended to be hypertensive. Diabetes was associated with a lower prevalence of high LDL but a higher prevalence of low HDL and high TG. Low physical activity was significantly associated with elevated TGs and low HDL-C. Current alcohol use was independently associated with a significantly lower prevalence of low HDL-C but not associated with other dyslipidemia types.

Figure 2.

Correlates of Dyslipidemia Patterns for All Hispanics

There were few differences across the Hispanic background groups with regards to correlates of dyslipidemia. BMI was consistently associated with dyslipidemia prevalence across all groups. Age was more strongly associated with higher prevalence of any dyslipidemia among Puerto Ricans; whereas female gender was a stronger correlate of higher prevalence of any dyslipidemia among Puerto Ricans compared to the other groups. Low PA and hypertension prevalence appeared to be more relevant among Puerto Ricans, being associated with significantly higher and lower odds of any dyslipidemia, respectively, among Puerto Ricans but not among the other groups. (Supplemental Figure)

Almost two-thirds and almost half of the population had abnormal LDL-C/HDL-C and TC/HDL-C ratios, respectively. Abnormal TC/HDL-C ratios were found most frequently among Central Americans and Cubans; less so among Dominicans (p<0.001). Abnormal LDL-C/HDL-C ratios were seen most frequently among Cubans and less so among Dominicans and Puerto Ricans (p<0.001). (Supplemental Table)

SES and acculturation

In the HCHS-SOL target population, the duration of residence in the US was not significantly associated with dyslipidemia prevalence. English-language preference was associated with lower prevalence of dyslipidemia compared to Spanish speakers, with findings consistent for every dyslipidemia type except low HDL-C which was consistently high regardless of language preference. Lower income was associated with higher prevalence of any dyslipidemia but most specifically for high TGs and low HDL-C. Among Hispanics/Latinos with higher educational attainment, prevalence rates of any dyslipidemia were significantly lower compared to those with lower levels of educational attainment regardless of the type of dyslipidemia. (Table 3)

Table 3.

Associations of SES and Acculturation Indicators with Dyslipidemia Pattern Prevalence*

| Any Dyslipidemia** N (%) |

P value |

High LDL | P value |

High TG | P value |

Low HDL | P value |

Non-HDL | P value |

Mixed Dyslipidemia |

P value |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Years in the Us | 0.90 | 0.14 | 0.10 | 0.62 | 0.33 | 0.36 | ||||||

| <10 years | 2,582 (65.1) | 1,493 (37.2) | 587 (13.6) | 1,620 (40.8) | 1,470 (35.5) | 433 (10.1) | ||||||

| 10+ years | 8,282 (64.9) | 4,704 (35.5) | 2,009 (15.2) | 5,098 (41.5) | 4,674 (34.4) | 1,420 (10.8) | ||||||

| <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | 0.56 | <0.001 | <0.001 | |||||||

| Language | ||||||||||||

| English | 1,921 (57.1) | 902 (26.6) | 365 (10.5) | 1,315 (40.7) | 856 (25.0) | 270 (8.1) | ||||||

| Spanish | 9,023 (67.6) | 5,335 (39.1) | 2,255 (16.2) | 5,454 (41.6) | 5,330 (37.9) | 1,601 (11.5) | ||||||

| Income | 0.05 | 0.54 | 0.04 | <0.001 | 0.93 | 0.04 | ||||||

| <20 | 4,855 (66.3) | 2,738 (36.1) | 1,229 (16.1) | 3,090 (43.8) | 2,736 (35.1) | 896 (11.9) | ||||||

| 21–40 | 3,399 (65.7) | 1,974 (36.7) | 804 (15.1) | 2,052 (40.9) | 1,961 (35.1) | 551 (10.2) | ||||||

| 41–75 | 1,292 (61.5) | 742 (35.1) | 294 (14.3) | 747 (37.1) | 728 (34.0) | 216 (11.1) | ||||||

| >75 | 415 (61.5) | 255 (39.4) | 74 (10.5) | 228 (32.0) | 225 (35.3) | 51 (7.3) | ||||||

| Education | 0.05 | 0.001 | 0.01 | 0.008 | 0.01 | 0.14 | ||||||

| <HS | 4,176 (67.0) | 2,312 (36.2) | 1,099 (16.3) | 2,614 (42.6) | 2,380 (36.0) | 791 (11.6) | ||||||

| HS | 2,720 (63.4) | 1,494 (32.8) | 603 (13.2) | 1,741 (43.1) | 1,459 (32.0) | 427 (9.8) | ||||||

| >HS | 3,795 (64.4) | 2,281 (37.9) | 854 (14.6) | 2,262 (39.1) | 2,209 (35.7) | 611 (10.4) |

All descriptive analyses use weighted frequencies and percentages

Defined as any of the following: LDL >=130, TG >=200, non-HDL >=160, TC >=240, Female and HDL < 50, Male and HDL <40, or Mixed dyslipidemia

Discussion

Dyslipidemia when defined comprehensively according to the NECP/ATP III guidelines,9 is highly prevalent among Hispanics/Latinos with almost 2/3 of the HCHS-SOL population exhibiting some form of dyslipidemia, particularly beyond the age of 40. Low HDL-C and elevated LDL-C were the most common types of dyslipidemia seen among Hispanics/Latinos. We found the overall prevalence of any dyslipidemia to be slightly higher among women compared to men, but this varied depending on the specific dyslipidemia type, with women more likely to have low HDL-C and men more likely to have high LDL-C, high TG, and high non-HDL-C. Except for low HDL-C, the prevalence of dyslipidemia increased with age, peaking at ages 45–64, and tapering off somewhat in those aged 65 to 74 years.

Few studies have systematically examined differences in lipid profiles across different Hispanic groups. One study among 928 ischemic stroke patients,16 found significant differences in lipid fractions, with lower LDL-C levels and higher TG levels in Mexicans compared to Caribbean-Hispanics (Dominicans, Cubans, Puerto Ricans) highlighting the potential heterogeneity of dyslipidemia among the Hispanic groups. To our knowledge, our study is the first to compare dyslipidemia among a broad range of Hispanic/Latino adults with a full complement of lipid and lipoprotein fractions. Our data show that although dyslipidemia prevalence rates were high across all Hispanic/Latinos, some groups fared worse than others. Individuals of Cuban and Central American descent seem particularly at risk. Those of Dominican descent seem at the lowest risk relative to other Hispanics/Latinos. The prevalence of elevated LDL-C and elevated non-HDL-C were highest among Cubans. Central Americans had the highest prevalence of high TGs. The prevalence of low HDL-C did not vary significantly across the groups. We found a high prevalence of abnormal TC-HDL-C ratios in the overall Hispanic/Latino population, particularly in Cubans and Central Americans, possibly reflecting an increased presence of small, dense LDL-C and other atherogenic apoB-containing particles.17 However, at this time, it is generally believed that cholesterol ratios do not provide additional prognostic information beyond the absolute cholesterol numbers when planning treatment.18

Our estimates of dyslipidemia are higher compared to those reported in other population-based studies such as the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES).1, 19 A meaningful comparison is difficult however, because of differences in time periods when prior studies were conducted, different study populations (Mexican-only or incomplete inclusion of Hispanic background groups), examination Hispanics/Latinos only as an aggregate single group and different and less rigorous definitions for dyslipidemia (total cholesterol only vs. the more comprehensive NCEP/ATP III definitions).

In the Minnesota Heart Survey, among mostly non-Hispanic whites, the mean prevalence of hypercholesterolemia (defined by TC >240mg/dl or use of antihyperlipidemics) was 23.9% for men and 17.3% for women.20 Data from NHANES 2007-10, the prevalence of hypercholesterolemia (defined by TC >240mg/dl) was 12.3% and 15.6% for non-Hispanic white men and women; 10.8% and 11.7% for non-Hispanic black men and women, respectively.21 For the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA), the prevalence of dyslipidemia (defined by abnormal LDL-C) was 19.7% and 8.4% for non-Hispanic white men and women; 18.2% and 14.0% for non-Hispanic black men and women, respectively.22 The Genetic Epidemiology Network of Arteriopathy study showed dyslipidemia prevalence (defined by abnormal LDL-C, HDL-C or TG) was greater among non-Hispanic whites than non-Hispanic blacks (women, 64.7% vs 49.5%; men, 78.4% vs 56.7%).23 Our higher prevalence of overall dyslipidemia and specific dyslipidemia types in our population of Hispanics/Latinos compared to published estimates among non-Hispanic whites and blacks is concerning and highlights persistent disparities as well as invalidating the prior notion of Hispanics/Latinos as a lower (or similar) risk group compared to non-Hispanic whites.

According to 2005-08 NHANES data, Mexican American men and women age 20 and older, 16.9% and 14.0%, respectively had total cholesterol levels ≥240 mg/dL and 42% and 32% had LDL-C levels ≥130mg/dL.1 Data from the 1982-84 Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examination Survey demonstrate variation in hypercholesterolemia prevalence between three Hispanic background groups—Mexicans, Cubans, and Puerto Ricans. However, women had the highest prevalence of hypercholesterolemia, with Puerto Ricans women having a prevalence of 20.6%.19 According to updated AHA statistics based on 2010 NHANES data,1 15.2% of Mexican men and 13.5% of Mexican women have TC levels ≥240mg/dL; 39.9% of men and 30.4% of women had LDL levels ≥130mg/dL; 34.2% of men and 15.1% of women had HDL-C levels less than 40mg/dL. When comparing these patterns to those observed in the HCHS-SOL target population, among Mexicans, the prevalence of elevated TC and LDL-C was only slightly lower in HCHS-SOL; however the prevalence of low HDL-C is significantly higher among the HCHS-SOL target population and worse among women, possibly due to the fact that gender-specific cutoffs for low HDL-C were used in our analysis.

Hispanics/Latinos residing in the US are not monolithic. They have variations in dietary patterns, different genetic racial ancestries, differential immigration patterns that may influence dyslipidemia. Ethnic differences in dietary intake have been shown to be associated with serum lipid levels in Hispanics/Latinos.24 As a group, Hispanics/Latinos face substantial socioeconomic adversity25 and poor healthcare access.25 In addition, Hispanics/Latinos often reside in unhealthy built environments26 that foster environmental and social risk factors such as lack of access to healthy foods, lack of places to walk and exercise, and poor access to primary care that can impact dyslipidemia prevalence. It is well known that race influences serum lipids. Studies have reported racial/ethnic variation in blood lipid levels, with lower TG and higher HDL-C among African Americans than in persons of European descent.27, 28 Interestingly, differences seem to exist between the genetic determinants of lipid profiles in African Americans and European Americans.29 It is possible that significant variation in the levels of African ancestry, Amerindian, and European ancestry across the diverse Hispanic/Latino background groups30 influenced serum lipid concentrations and dyslipidemia prevalence.

Of note, a lower prevalence of dyslipidemia was seen among Dominican-origin Hispanics/Latinos – a finding that persisted for most types of dyslipidemia. Not much has been published about Hispanics of Dominican background, who account for ∼3% of US Hispanics/Latinos. The Dominican community is primarily composed of more recent immigrants over the last 30–40 years.31 Their more recent immigration and possible increased retainment of traditional cultural values and norms may contribute to the observed trend in dyslipidemia. Another possibility is that there may be greater African ancestry in Dominican-origin Hispanics/Latinos,32 thus a greater likelihood for a healthier lipid profile with lower TG and higher HDL-C.

Socioeconomic status and acculturation were significantly related to dyslipidemia across all Hispanics/Latinos. Lower educational attainment and Spanish-language preference were consistent correlates of dyslipidemia prevalence. There have been few reports examining the cross-sectional relationships between acculturation measures and lipoprotein levels among Hispanics/Latinos. The MESA showed that Spanish-language preference Hispanics/Latinos and those who had lived a longer proportion of life in the US had significantly higher LDL-C than English-language preference Hispanics/Latinos and those who had fewer years in the US.33 Our findings suggest that dyslipidemia prevalence among Hispanic/Latino individuals is reduced by English-language preference and increasing educational attainment possibly because of the acquisition of skills required to navigate the healthcare system. Thus, the relationship between greater acculturation and lower prevalence of dyslipidemia may be largely driven by higher rates of diagnosis and more accessible treatment.

Study Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of this study include its population-based sampling frame and the availability of comprehensive lipid and lipoprotein measurements to determine undiagnosed and diagnosed dyslipidemia prevalence and NCEP / ATP III goal attainment. A limitation is that given our focus on the specific dyslipidemia types, dyslipidemia prevalence needed to be based on actual measured serum lipid and lipoprotein levels and not on lipid-lowering medication use. Thus, it is likely that any dyslipidemia prevalence is actually underestimated in our study. Our study is also limited by its descriptive and cross-sectional nature thus precluding any inferences of causality. The HCHS/SOL is a multisite study representative of specific US geographic areas and is not nationally representative. Inferences beyond these regions may not be fully appropriate.

In conclusion, the US Hispanic/Latino population has a high prevalence of dyslipidemia. Certain specific groups defined by country of heritage, sociodemographic or sociocultural characteristics are disproportionately affected. These findings can hopefully inform and contribute to the development of effective and comprehensive public health strategies that improve the cardiovascular health of Hispanics/Latinos in the US.

Supplementary Material

Dyslipidemia is highly prevalent among all US Hispanics/Latinos; Cubans are at particularly high risk.

Determinants of dyslipidemia varied across Hispanic backgrounds; measures of socioeconomic status and acculturation were significantly related to dyslipidemia prevalence.

This information can help guide public health measures and can be useful in efforts to eliminate cardiovascular risk factor disparities in the US Hispanic/Latino population.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the staff and participants of HCHS/SOL for their important contributions.

Funding/Support: The Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos was carried out as a collaborative study supported by contracts from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) to the University of North Carolina (N01-HC65233), University of Miami (N01-HC65234), Albert Einstein College of Medicine (N01-HC65235), Northwestern University (N01-HC65236), and San Diego State University (N01-HC65237).

This study was partially supported by NHLBI grant R01 HL104199 (Epidemiologic Determinants of Cardiac Structure and Function among Hispanics: Carlos J. Rodriguez, MD, MPH Principal Investigator).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Dr. Rodriguez had full access to the data and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. All authors have read and approved the paper, have met the criteria for authorship as established by the International Committee of Medical Journals Editors, certify that the paper represents honest work, and are able to verify the validity of the results reported.

Disclosure: There are no conflicts to disclose related to the research presented in this manuscript.

References

- 1.Go AS, Mozaffarian D, Roger VL, Benjamin EJ, Berry JD, Borden WB, Bravata DM, Dai S, Ford ES, Fox CS, Franco S, Fullerton HJ, Gillespie C, Hailpern SM, Heit JA, Howard VJ, Huffman MD, Kissela BM, Kittner SJ, Lackland DT, Lichtman JH, Lisabeth LD, Magid D, Marcus GM, Marelli A, Matchar DB, McGuire DK, Mohler ER, Moy CS, Mussolino ME, Nichol G, Paynter NP, Schreiner PJ, Sorlie PD, Stein J, Turan TN, Virani SS, Wong ND, Woo D, Turner MB. Heart disease and stroke statistics--2013 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2013;127:e6–e245. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e31828124ad. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rodriguez CJ, Brenes J. Hypercholesterolemia in Minorities. In: Chavez-Tapia MUe NC, editor. Topics in prevalent diseases: A minority’s perspective. Hauppauge, NY: Nova Science Publishers; 2008. pp. 125–136. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winkleby MA, Kraemer HC, Ahn DK, Varady AN. Ethnic and socioeconomic differences in cardiovascular disease risk factors: findings for women from the Third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1988–1994. JAMA : the journal of the American Medical Association. 1998;280:356–362. doi: 10.1001/jama.280.4.356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wei M, Mitchell BD, Haffner SM, Stern MP. Effects of cigarette smoking, diabetes, high cholesterol, and hypertension on all-cause mortality and cardiovascular disease mortality in Mexican Americans The San Antonio Heart Study. American journal of epidemiology. 1996;144:1058–1065. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a008878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fulton-Kehoe DL, Eckel RH, Shetterly SM, Hamman RF. Determinants of total high density lipoprotein cholesterol and high density lipoprotein subfraction levels among Hispanic and non-Hispanic white persons with normal glucose tolerance: the San Luis Valley Diabetes Study. Journal of clinical epidemiology. 1992;45:1191–1200. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(92)90160-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sorlie PD, Aviles-Santa LM, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Kaplan RC, Daviglus ML, Giachello AL, Schneiderman N, Raij L, Talavera G, Allison M, Lavange L, Chambless LE, Heiss G. Design and implementation of the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20:629–641. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.03.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lavange LM, Kalsbeek WD, Sorlie PD, Aviles-Santa LM, Kaplan RC, Barnhart J, Liu K, Giachello A, Lee DJ, Ryan J, Criqui MH, Elder JP. Sample design and cohort selection in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Annals of epidemiology. 2010;20:642–649. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Friedewald WT, Levy RI, Fredrickson DS. Estimation of the concentration of low-density lipoprotein cholesterol in plasma, without use of the preparative ultracentrifuge. Clinical chemistry. 1972;18:499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Executive Summary of The Third Report of The National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) Expert Panel on Detection, Evaluation, And Treatment of High Blood Cholesterol In Adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) Jama. 2001;285:2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McLaughlin T, Abbasi F, Cheal K, Chu J, Lamendola C, Reaven G. Use of metabolic markers to identify overweight individuals who are insulin resistant. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:802–809. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-10-200311180-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gordon T, Castelli WP, Hjortland MC, Kannel WB, Dawber TR. High density lipoprotein as a protective factor against coronary heart disease. The Framingham Study. Am J Med. 1977;62:707–714. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(77)90874-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.St-Pierre AC, Cantin B, Dagenais GR, Mauriege P, Bernard PM, Despres JP, Lamarche B. Low-density lipoprotein subfractions and the long-term risk of ischemic heart disease in men: 13-year follow-up data from the Quebec Cardiovascular Study. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:553–559. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000154144.73236.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.American Diabetes A. Diagnosis and classification of diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(Suppl 1):S62–S69. doi: 10.2337/dc10-S062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daviglus ML, Talavera GA, Aviles-Santa ML, Allison M, Cai J, Criqui MH, Gellman M, Giachello AL, Gouskova N, Kaplan RC, LaVange L, Penedo F, Perreira K, Pirzada A, Schneiderman N, Wassertheil-Smoller S, Sorlie PD, Stamler J. Prevalence of major cardiovascular risk factors and cardiovascular diseases among Hispanic/Latino individuals of diverse backgrounds in the United States. JAMA. 2012;308:1775–1784. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.14517. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rao JNK, Scott AJ. On simple adjustments to chi-squared tests with survey data. Annals of Statistics. 1987;15:385–397. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Romano JG, Arauz A, Koch S, Dong C, Marquez JM, Artigas C, Merlos M, Hernandez B, Roa LF, Rundek T, Sacco RL. Disparities in stroke type and vascular risk factors between 2 Hispanic populations in Miami and Mexico city. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2013;22:828–833. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2012.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ridker PM, Rifai N, Cook NR, Bradwin G, Buring JE. Non-HDL cholesterol, apolipoproteins A-I and B100, standard lipid measures, lipid ratios, and CRP as risk factors for cardiovascular disease in women. JAMA. 2005;294:326–333. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.3.326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ray KK, Cannon CP, Cairns R, Morrow DA, Ridker PM, Braunwald E. Prognostic utility of apoB/AI, total cholesterol/HDL, non-HDL cholesterol, or hs-CRP as predictors of clinical risk in patients receiving statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes: results from PROVE IT-TIMI 22. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:424–430. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.181735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Crespo C, Loria C, Burt V. Hypertension and other cardiovascular disease risk factors among Mexican Americans, Cuban Americans, and Puerto Ricans from the Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Public Health Reports. 1996;111(Suppl. 2):7–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Arnett DK, Jacobs DR, Jr, Luepker RV, Blackburn H, Armstrong C, Claas SA. Twenty-year trends in serum cholesterol, hypercholesterolemia, and cholesterol medication use: the Minnesota Heart Survey, 1980–1982 to 2000–2002. Circulation. 2005;112:3884–3891. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.549857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ford ES, Li C, Pearson WS, Zhao G, Mokdad AH. Trends in hypercholesterolemia, treatment and control among United States adults. International Journal of Cardiology. 2010;140:226–235. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2008.11.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goff DC, Jr, Bertoni AG, Kramer H, Bonds D, Blumenthal RS, Tsai MY, Psaty BM. Dyslipidemia prevalence, treatment, and control in the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis (MESA): gender, ethnicity, and coronary artery calcium. Circulation. 2006;113:647–656. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.552737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.O’Meara JG, Kardia SL, Armon JJ, Brown CA, Boerwinkle E, Turner ST. Ethnic and sex differences in the prevalence, treatment, and control of dyslipidemia among hypertensive adults in the GENOA study. Archives of Internal Medicine. 2004;164:1313–1318. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.12.1313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bermudez OI, Velez-Carrasco W, Schaefer EJ, Tucker KL. Dietary and plasma lipid, lipoprotein, and apolipoprotein profiles among elderly Hispanics and non-Hispanics and their association with diabetes. The American journal of clinical nutrition. 2002;76:1214–1221. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/76.6.1214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.DeNavas-Walt C, Proctor BD, Smith JC. Income, Poverty, and Health Insurance Coverage in the United States: 2011 Current Population Reports. 2012:P60–P243. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lovasi GS, Hutson MA, Guerra M, Neckerman KM. Built environments and obesity in disadvantaged populations. Epidemiologic reviews. 2009;31:7–20. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxp005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rodriguez C, Pablos-Mendez A, Palmas W, Lantigua R, Mayeux R, Berglund L. Comparison of modifiable determinants of lipids and lipoprotein levels among African-Americans, Hispanics, and Non-Hispanic Caucasians > or =65 years of age living in New York City. Am J Cardiol. 2002;89:178–183. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)02197-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sorlie PD, Sharrett AR, Patsch W, Schreiner PJ, Davis CE, Heiss G, Hutchinson R. The relationship between lipids/lipoproteins and atherosclerosis in African Americans and whites: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities Study. Annals of Epidemiology. 1999;9:149–158. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(98)00063-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Deo RC, Reich D, Tandon A, Akylbekova E, Patterson N, Waliszewska A, Kathiresan S, Sarpong D, Taylor HA, Jr, Wilson JG. Genetic differences between the determinants of lipid profile phenotypes in African and European Americans: the Jackson Heart Study. PLoS genetics. 2009;5:e1000342. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Price AL, Patterson N, Yu F, Cox DR, Waliszewska A, McDonald GJ, Tandon A, Schirmer C, Neubauer J, Bedoya G, Duque C, Villegas A, Bortolini MC, Salzano FM, Gallo C, Mazzotti G, Tello-Ruiz M, Riba L, Aguilar-Salinas CA, Canizales-Quinteros S, Menjivar M, Klitz W, Henderson B, Haiman CA, Winkler C, Tusie-Luna T, Ruiz-Linares A, Reich D. A genomewide admixture map for Latino populations. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;80:1024–1036. doi: 10.1086/518313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.US Census Bureau. The Hispanic Population in the United States: 2010 Census Briefs. May 2011; [Google Scholar]

- 32.Manichaikul A, Palmas W, Rodriguez CJ, Peralta CA, Divers J, Guo X, Chen WM, Wong Q, Williams K, Kerr KF, Taylor KD, Tsai MY, Goodarzi MO, Sale MM, Diez-Roux AV, Rich SS, Rotter JI, Mychaleckyj JC. Population structure of Hispanics in the United States: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis. PLoS genetics. 2012;8:e1002640. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002640. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Eamranond P, Legedza A, Diez-Roux A, Kandule N, Palmas W, Siscovick D, Makamal K. Association between language and risk factor levels among Hispanic adults with hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, or diabetes. American Heart Journal. 2009;157:53–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2008.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.