ABSTRACT

Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) are an urgent public health concern. Rapid identification of the resistance genes, their mobilization capacity, and strains carrying them is essential to direct hospital resources to prevent spread and improve patient outcomes. Whole-genome sequencing allows refined tracking of both chromosomal traits and associated mobile genetic elements that harbor resistance genes. To enhance surveillance of CREs, clinical isolates with phenotypic resistance to carbapenem antibiotics underwent whole-genome sequencing. Analysis of 41 isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae and Enterobacter cloacae, collected over a 3-year period, identified K. pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC) genes encoding KPC-2, −3, and −4 and OXA-48 carbapenemases. All occurred within transposons, including multiple Tn4401 transposon isoforms, embedded within more than 10 distinct plasmids representing incompatibility (Inc) groups IncR, -N, -A/C, -H, and -X. Using short-read sequencing, draft maps were generated of new KPC-carrying vectors, several of which were derivatives of the IncN plasmid pBK31551. Two strains also had Tn4401 chromosomal insertions. Integrated analyses of plasmid profiles and chromosomal single-nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) profiles refined the strain patterns and provided a baseline hospital mobilome to facilitate analysis of new isolates. When incorporated with patient epidemiological data, the findings identified limited outbreaks against a broader 3-year period of sporadic external entry of many different strains and resistance vectors into the hospital. These findings highlight the utility of genomic analyses in internal and external surveillance efforts to stem the transmission of drug-resistant strains within and across health care institutions.

IMPORTANCE

We demonstrate how detection of resistance genes within mobile elements and resistance-carrying strains furthers active surveillance efforts for drug resistance. Whole-genome sequencing is increasingly available in hospital laboratories and provides a powerful and nuanced means to define the local landscape of drug resistance. In this study, isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae and Enterobacter cloacae with resistance to carbapenem antibiotics were sequenced. Multiple carbapenemase genes were identified that resided in distinct transposons and plasmids. This mobilome, or population of mobile elements capable of mobilizing drug resistance, further highlighted the degree of strain heterogeneity while providing a detailed timeline of carbapenemase entry into the hospital over a 3-year period. These surveillance efforts support effective targeting of infection control resources and the development of institution-specific repositories of resistance genes and the mobile elements that carry them.

INTRODUCTION

Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae (CRE) are an urgent problem since they cause infections with high morbidity and mortality and lengthen hospital stays (1, 2). Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases (KPCs) most commonly confer carbapenem resistance among members of the Enterobacteriaceae. These class A serine beta-lactamases were first detected in 1996 in North Carolina and have subsequently spread worldwide (3). Among the 22 characterized variants (http://www.lahey.org/studies), KPC-2 and −3 occur most commonly (4), along with less common carbapenemases that include OXA-48, NDM, and VIM (5). Phenotypic resistance to carbapenem antibiotics can also occur with noncarbapenemase beta-lactamases, such as AmpC, and extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBLs) when they occur with chromosomal porin defects and the AmpD and AmpR regulatory proteins (6, 7).

KPC genes commonly occur on Tn4401, a 10-kb Tn3 family element flanked by 38-bp inverted repeats and containing two interrupting insertion sequences (IS), ISKpn6 and ISKpn7 (8). Tn4401 has 5 isoforms, denoted as a to e, that are differentiated by deletions upstream from the KPC gene (8). Transposition generates identical 5-bp terminal direct repeats (TDR) at the insertion site (8). Tn4401 has been identified in many plasmids and in chromosomal insertions (8–10). Other carbapenemases are associated with different transposons, such as OXA-48 gene carriage by the Tn1999 transposon (11).

When present on mobile elements, carbapenem resistance may spread clonally and through inter- and intraspecies lateral gene transfer. Each mechanism presents different epidemiological risks within health care systems. Integrated analyses of chromosomal, plasmid, and transposable elements within strains can better support hospital surveillance by identifying resistance-carrying strains and the risks for intra- and interspecies transfer of mobile elements harboring resistance determinants over time (10, 12–14).

We used whole-genome sequencing of carbapenem-resistant clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae and Enterobacter cloacae to establish a hospital-specific database of resistance determinants, their genomic context, and time points of entry within the health care system. The resulting data set provided a locally informed genomic landscape of resistance genes and carrying vectors, used to support ongoing analyses and infection control efforts.

RESULTS

Carbapenem resistance in hospital isolates of K. pneumoniae and E. cloacae.

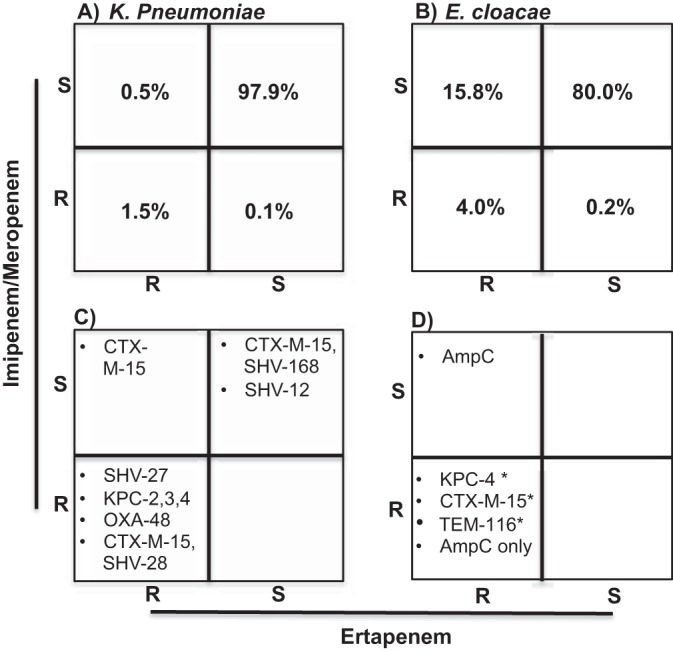

Phenotypic susceptibility testing identified unique populations of putative CREs and raised concerns regarding clonal populations within the hospital (Fig. 1). Among all K. pneumoniae isolates, 1.5% demonstrated resistance to ertapenem and imipenem and/or meropenem, while an additional 0.5% of isolates were resistant to ertapenem but susceptible to both imipenem and meropenem and 98% of strains were carbapenem susceptible (Fig. 1A). In contrast, 4.0% of Enterobacter cloacae isolates demonstrated pancarbapenem resistance, with 15.8% showing resistance to ertapenem but susceptibility to imipenem and meropenem (Fig. 1B). A cohort of 41 clinical isolates of K. pneumoniae and E. cloacae (see Table S1 in the supplemental material) underwent whole-genome sequencing to identify resistance determinants, their genomic contexts, and strain patterns over time.

FIG 1 .

Carbapenem genotype-phenotype correlations of K. pneumoniae and E. cloacae. Percentages of phenotypic resistance to ertapenem and imipenem/meropenem in K. pneumoniae (A) and E. cloacae (B) isolates for all isolates cultured from 2011 to 2015. (C and D) Carbapenemases and ESBLs identified in sequenced isolates of K. pneumoniae (C) and E. cloacae (D). Asterisks indicate strains where the beta-lactamases also included a chromosomally encoded AmpC.

Genomic context of carbapenemases and other beta-lactamases.

Among the isolates sequenced, 17 strains had a carbapenemase gene that was detectable by genome sequencing (see Table S2 in the supplemental material). Targeted PCRs for KPC and OXA-48 genes confirmed these results (data not shown). Carbapenemase-producing strains also carried between 2 and 5 additional beta-lactamases, including CTX-M-15, as well as SHV, TEM, and OXA family enzymes. KPC-2 and KPC-3 occurred most commonly in K. pneumoniae strains, though KPC-4 and OXA-48 were also detected (Fig. 1C). In contrast, E. cloacae isolates with carbapenemases uniformly carried KPC-4 with 2 to 3 additional beta-lactamases, including a chromosomally encoded AmpC family enzyme (ACT and MIR family), as well as mobile OXA and TEM family enzymes (Fig. 1D; see also Table S2 in the supplemental material).

Among strains with phenotypic carbapenem resistance that did not harbor a detectable carbapenemase gene, 0 to 4 other beta-lactamase genes were identified per strain (Fig. 1C and D; see also Table S3 in the supplemental material). Carbapenemase gene-negative isolates of K. pneumoniae commonly carried chromosomal copies of SHV and Len family narrow-spectrum beta-lactamase genes. Four strains (BWH-NC5, -NC6, -NC7, and -NC36) (“BWH” in the strain designations denotes Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and “NC” denotes non-carbapenemase-carrying strains) also carried the epidemic ESBL CTX-M-15, along with OXA-1 (BWH-NC6) or OXA-1 with TEM-1 (BWH-NC7 and BWH-NC36). Of the E. cloacae non-carbapenemase-producing strains, all harbored chromosomally encoded AmpC family beta-lactamases, while BWH-NC28 and BWH-NC17 also carried (respectively) mobile-element-encoded CTX-M-15 and TEM-116 extended-spectrum beta-lactamases in addition to the chromosomal AmpC (Fig. 1D; see also Table S3). Interestingly, BWH-NC18, a highly resistant strain isolated 1 month previously from the same patient as BWH-NC17, did not have a detectable TEM-116 gene.

Phenotype-genotype concordance among carbapenemase-producing K. pneumoniae and E. cloacae isolates.

All isolates harboring a KPC carbapenemase gene demonstrated phenotypic resistance to ertapenem, imipenem, and meropenem (Fig. 1; see also Table S2 in the supplemental material). However, panresistance also occurred through other mechanisms, highlighted by the finding that 32.4% of meropenem-resistant strains, 39.5% of imipenem-resistant strains, and 52.3% of ertapenem-resistant strains did not carry a carbapenemase gene that was detectable by sequencing or targeted PCR (data not shown). Genome sequencing in these strains identified non-KPC etiologies, including other beta-lactamase genes in conjunction with disruptions in the genes encoding porins OmpC (OmpK36) and OmpF (OmpK35) or mutations in the gene encoding the AmpC-regulator AmpD (Fig. 1C and D; see also Tables S3 and S4) (6, 7, 15–19).

Transposon carriage of carbapenemase genes.

All KPC genes occurred in the context of Tn4401 transposons (Table 1). Among these, Tn4401a and Tn4401e isoforms were found to be carrying KPC-2 genes and the Tn4401b isoform was found to be carrying KPC-3 and KPC-4 genes. While the majority of KPC strains harbored only a single copy of Tn4401, transposon insertion site analyses identified two Tn4401 copies in BWH-C6 (carbapenemase carriage is denoted by “C” in the strain designation), one chromosomal and one plasmid borne, highlighting the capacity for the transposon cassette to mobilize within carrying strains.

TABLE 1 .

Genomic context and transposon or plasmid identities in carbapenemase gene-carrying isolates

| Strain | Speciesa | BLA(s)b | Transposon(s) | Plasmid Inc group(s) or genomic location | Plasmid or MEc | Closest reference plasmid | % identity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BWH-C1 | KP | KPC-2 | Tn4401a | IncR | pKPC-484 | pKPC-484 | >99 |

| BWH-C2 | KP | KPC-2 | Tn4401a | IncR | pKPC-484 | pKPC-484 | >99 |

| BWH-C3 | KP | KPC-4 | Tn4401b (interrupted by IS110) | IncN | pBWH-C3-KPC | pBK31551 | 75 |

| BWH-C4 | KP | OXA-48 | Tn1999 | IncL/M | E71T | E71T | >99 |

| BWH-C5 | KP | KPC-3 | Tn4401b | Chromosomal | |||

| BWH-C6 | KP | KPC-3 | Tn4401b | Chromosomal | |||

| KP | KPC-3 | Tn4401b | IncI2 | pBK15692 | pBK15692 | 98 | |

| BWH-C7 | KP | KPC-2 | Tn4401e | IncA/C2 | pBWH-C7-KPC | PR55 | 97 |

| BWH-C8 | KP | KPC-3 | Tn4401b | Untypeable | p34399-43.500kb | p34399-43.500kb | 98 |

| BWH-C9 | KP | KPC-3 | Tn4401b | IncX3 | pBWH-C9-KPC | p34618-43.380kb | >99 |

| BWH-C10 | KP | KPC-3 | Tn4401b | Untypeable | p34399-43.500kb | p34399-43.500kb | 98 |

| BWH-C11 | EC | TEM-1, OXA-1, KPC-4 | Tn4401b (interrupted by Tn6901) | Unresolvable plasmid | ME-BWH-C11-KPC | pBK31551 | 90 |

| BWH-C12 | EC | TEM-1, OXA-1, KPC-4 | Tn4401b (interrupted by Tn6901) | Unresolvable plasmid | ME-BWH-C11-KPC | pBK31551 | 90 |

| BWH-C13 | EC | KPC-4 | Tn4401b | IncH12A/IncH12 | pBWH-C13-KPC | pK29 | 91 |

| BWH-C14 | EC | KPC-4 | Tn4401b | IncH12A/IncH12 | pBWH-C13-KPC | pK29 | 91 |

| BWH-C15 | EC | KPC-4 | Tn4401b | IncH12A/IncH12 | pBWH-C13-KPC | pK29 | 91 |

| BWH-C16 | EC | KPC-4 | Tn4401b | IncN | pBWH-C16-KPC | pBK31551 | 85 |

| BWH-C17 | EC | KPC-4 | Tn4401b | IncN | pBWH-C16-KPC | pBK31551 | 85 |

KP, Klebsiella pneumoniae; EC, Enterobacter cloacae.

BLA, beta-lactamase; KPC, Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase.

ME, mobile element.

In addition to KPC carbapenemase genes in the context of Tn4401, one instance of the OXA-48 carbapenemase gene was also found, on Tn1999 inserted in an incompatibility (Inc) group IncL/M plasmid in K. pneumoniae strain BWH-C4 (20, 21).

Klebsiella plasmids.

Carbapenemase gene-carrying transposons were borne by members of Inc group IncR, -N, -L/M, -I, and -X plasmids in Klebsiella (Table 1). While repetitive sequences can make plasmid assembly with short reads challenging, improved finished plasmid references in GenBank supported the creation of draft plasmid maps for most strains. These analyses identified several known KPC-carrying vectors, including pKPC-484 (strains BWH-C1 and -C2) (10), E71T (strain BWH-C4) (21), pBK15692 (strain BWH-C6) (22), and p34399-43.500kb (strains BWH-C8 and -C10) (GenBank accession number CP010387.1).

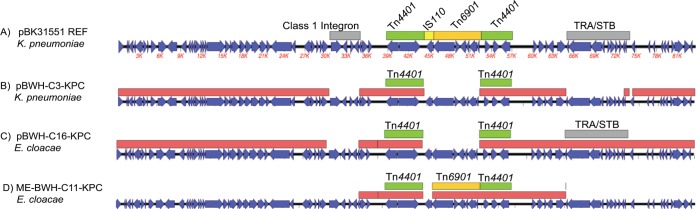

The analyses also identified vectors without close references. Strain BWH-C3’s plasmid, pBWH-C3-KPC, carried a KPC-4 gene (see Fig. S1a in the supplemental material). The plasmid backbone demonstrated only 75% identity to pBK31551, a plasmid that had Tn4401 interrupted by IS110 and Tn6901 elements (Fig. 2a) (23). However, unlike pBK31551, pBWH-C3-KPC lacks these interrupting elements (Fig. 2b). pBWH-C3-KPC also lacked the class I integron, an ISCRI element located upstream from Tn4401, and a region of plasmid transfer and stability machinery (Fip, Tra, and Stb genes) (Fig. 2b).

FIG 2 .

pBK31551-derived mobile elements. (A) The pBK31551 sequence is shown, with open reading frames (ORFs) in blue, KPC gene-carrying Tn4401 transposons in green, other insertion sequences and transposons in orange, and class I integron sequences in grey. (B to D) Red boxes indicate homologous regions of pBK31551. (B) pBWH-C3-KPC lacks regions that correspond to class I integron resistance, Tra/Stb factors, and the IS110 and Tn6901 mobile elements within Tn4401. (C) pBWH-C16-KPC lacks the same regions except for Tra/Stb (grey box). (D) ME-BWH-C11-KPC covers an ~30-kb region of pBK31551 that includes Tn4401 (interrupted by Tn6901 [orange box]). This construct does not include the IS110 insertion found in the parent pBK31551 construct (yellow box in panel A).

Other plasmid vectors, previously described as non-KPC plasmids, were found with Tn4401 insertions. Strain BWH-C7 (KPC-2) carried an IncA/C plasmid with 97% sequence identity to PR55 (see Fig. S1b in the supplemental material), first identified in a clinical isolate of K. pneumoniae from France in 1969 (24). In this plasmid, designated pBWH-C7-KPC, Tn4401e inserted between the ter and kfrA genes (see Fig. S1b). In plasmid pBWH-C9-KPC, carried in strain BWHC9, Tn4401b inserted into an oxidoreductase gene in an IncX plasmid with >99% identity to p34618-43.380kb (unpublished data; GenBank accession number CP010395.1) (see Fig. S1c). This construct bears a close relationship to pKPSn90, a KPC-3-bearing IncX plasmid with Tn4401 inserted at a different location than in pBWH-C9-KPC (25).

While the majority of strains carried Tn4401 in a plasmid backbone, K. pneumoniae strains BWH-C5 and BWH-C6 carried chromosomal insertions. BWH-C6 also harbored a plasmid copy of Tn4401 in pBK15692. Interestingly, strain BWH-C5 also carried plasmid pBK15692, though Tn4401 appears to have been excised, highly suggestive of a transposon jump from pBK15692 to the chromosome in these strains (see Fig. S2a and b in the supplemental material).

Enterobacter plasmids.

KPC carriage has been less well characterized in Enterobacter species than in Klebsiella species. In this cohort, carbapenemase-bearing strains of E. cloacae contained a single, plasmid-borne copy of KPC-4 within Tn4401b. Mobile element analyses of these strains further identified three subgroups.

Group 1 strains carried mobile element ME-C11-KPC, which harbors Tn4401::blaKPC-4 and TEM-1 and OXA-1 genes in an approximately 28-kb segment with 100% identity to the IncN plasmid pBK31551, originally detected in K. pneumoniae (Fig. 2d). Of the two mobile elements that disrupt the Tn4401 insertion in pBK31551, IS1618 (IS110 family) and Tn6901, only Tn6901 is present. However, the group 1 Enterobacter cloacae strains lack the IS110 insertion but have the Tn6901 insertion. This strain carries two other Enterobacter plasmids with >99% identity to p35374-141.404kb and p34399-106.698kb, neither of which has been described as carrying a KPC or other beta-lactamase gene. With short-read analyses, it was not possible to link ME-BWH-C11-KPC into a larger plasmid backbone; however, the raw-read coverage was approximately 2× that of the plasmids, suggesting that the segment occurred as a duplication that collapsed into a chimeric contig, as described by Conlan et al. (10).

Group II strains, whose mobile elements are represented by pBWH-C13-KPC (see Fig. S1d in the supplemental material) carried a KPC-4 gene on Tn4401b embedded in a plasmid with 91% identity to the IncHI2 plasmid, pK29 (26). This construct was originally isolated from K. pneumoniae in Taiwan and shown to be negative for a KPC gene but carried the AmpC beta-lactamase CMY-8 gene and the ESBL CTX-M-3 gene, neither of which occurred in the backbone identified in plasmid pBWH-C13-KPC, though an OXA-129 gene was identified.

Group III strains, whose mobile elements are represented by pBWH-C16-KPC (Fig. 2C; see also Fig. S1e in the supplemental material), carried a KPC-4 gene on Tn4401b, along with TEM-1 on an IncN plasmid with 85% identity to pBK31551. This construct is quite similar to pBWH-C3-KPC (Fig. 2) in that the transposon is not disrupted by either of the mobile elements found in pBK31551. It additionally lacks the same regions of the upstream class I integron. However, unlike pBWH-C3-KPC, this construct contains the Tra/Stb-encoding region found downstream from the KPC-encoding region (Fig. 2C).

Epidemiology of carbapenemase elements over time.

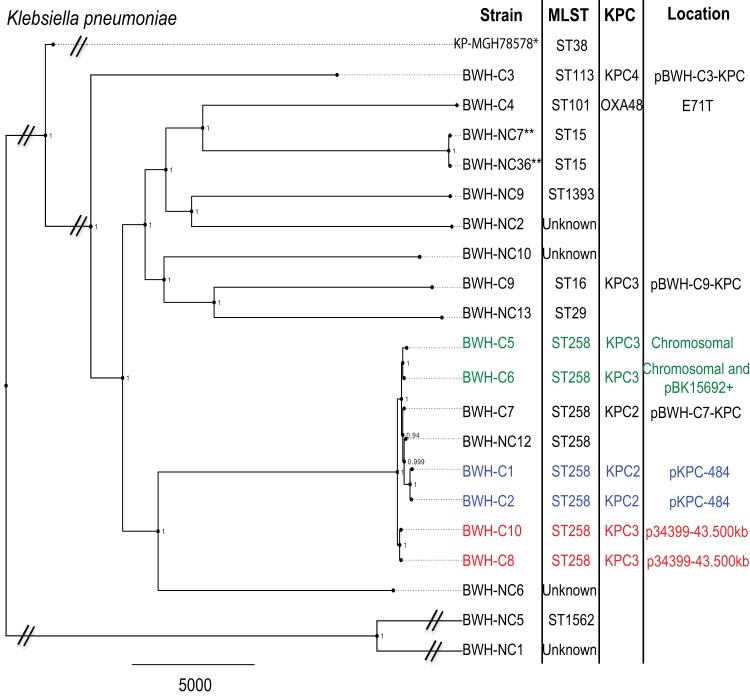

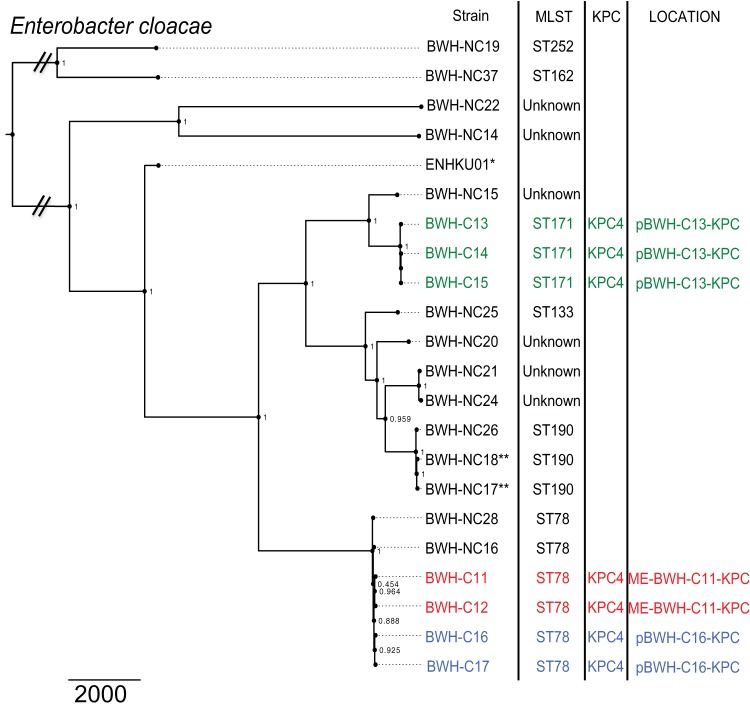

To evaluate similarities among carbapenemase-carrying strains, distance trees based on core chromosomal single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were compared with the strains’ multilocus sequence types (MLSTs), carbapenemase genes, and transposon and plasmid carriage profiles (Fig. 3 and 4).

FIG 3 .

Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree of K. pneumoniae clinical isolates. SNPs in the core chromosome (excluding mobile elements) were calculated using strain KP-MGH-78578 as a reference (indicated by an asterisk). Isolates taken from the same patient (during separate inpatient stays) are denoted by double asterisks. Corresponding MLSTs, KPC variants, and carbapenemase gene-bearing plasmids (if present) are indicated. Strains with similar KPC gene-bearing constructs, i.e., chromosomal/pBK15692 (green), pKPC-484 (blue), and p34399-43.500kb (red), are indicated. Scale bar indicates a distance of 5,000 SNPs. Local support values are indicated at the nodes.

FIG 4 .

Maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree of E. cloacae clinical isolates. SNPs in the core chromosome (excluding mobile elements) were calculated using strain KP-ENHKUO1 as a reference (indicated by an asterisk). Isolates taken from the same patient (during separate inpatient stays) are denoted by double asterisks. Corresponding MLSTs, KPC variants, and carbapenemase gene-bearing plasmids (if present) are indicated. Strains with similar KPC-bearing constructs, i.e., pBWH-C13-KPC (green), pBWH-C16-KPC (blue), and ME-BWH-C11-KPC (red) are indicated. Scale bar indicates a distance of 2,000 SNPs. Local support values are indicated at the nodes.

For K. pneumoniae strains, the major branches corresponded to a variety of MLSTs (Fig. 3), including ST258 (8 strains), the major KPC-bearing clone in the United States (8). Additional MLST types included ST15 (n = 2), ST38, ST113, ST16, ST29, ST101, ST1562, and ST1393 (n = 1 each) and several strains with an unknown ST (n = 4). A single pancarbapenem-resistant ST258 strain, BWH-NC12, did not have a carbapenemase gene that was detectable by sequencing or targeted PCR but demonstrated disrupted OmpK35 and OmpK36 porin genes, likely contributing to its highly resistant phenotype (see Table S4 in the supplemental material).

The numbers of SNPs separating K. pneumoniae isolates in this study ranged widely, from 8 to 35,520 (Table 2). Among the ST258 isolates, strains differed by 35 to 612 SNPs. Two sets of KPC strains that carried identical plasmids and were cultured from different patients, BWH-C1 and -C2 and BWH-C8 and -C10, differed by 106 and 35 SNPs, respectively. Strains BWH-C5 and BWH-C6, which harbored chromosomal Tn4401 insertions in the same location, differed by 171 SNPs, suggesting that they are related but not immediately so. Furthermore, BWH-C6 also harbored a second copy of Tn4401 in pBK15692, suggesting an additional transposition event in an ancestor in common with BWH-C5.

TABLE 2 .

SNP matrix for Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates

| Strain | No. of SNPs that differ between indicated strains |

|||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BWH-C1 | BWH-C2 | BWH-C3 | BWH-C4 | BWH-C5 | BWH-C6 | BWH-C7 | BWH-C8 | BWH-C9 | BWH-C10 | BWH-NC1 | BWH-NC2 | BWH-NC5 | BWH-NC6 | BWH-NC7 | BWH-NC9 | BWH-NC10 | BWH-NC12 | BWH-NC13 | BWH-NC36 | |

| BWH-C1 | 0 | 106 | 16,131 | 17,219 | 539 | 400 | 349 | 612 | 16,533 | 601 | 32,692 | 17,009 | 34,958 | 15,714 | 17,001 | 16,961 | 16,359 | 373 | 16,671 | 16,999 |

| BWH-C2 | 106 | 0 | 16,126 | 17,221 | 481 | 344 | 293 | 556 | 16,533 | 549 | 32,713 | 17,008 | 34,977 | 15,698 | 16,998 | 16,961 | 16,358 | 321 | 16,673 | 16,996 |

| BWH-C3 | 16,131 | 16,126 | 0 | 17,033 | 16,127 | 16,094 | 16,093 | 16,064 | 16,311 | 16,047 | 32,209 | 16,632 | 34,566 | 16,913 | 16,915 | 16,813 | 16,388 | 16,135 | 16,245 | 15,814 |

| BWH-C4 | 17,219 | 17,221 | 17,033 | 0 | 17,248 | 17,202 | 17,207 | 17,176 | 16,659 | 17,162 | 33,115 | 16,965 | 35,520 | 16,860 | 16,290 | 16,770 | 16,937 | 17,241 | 17,094 | 16,288 |

| BWH-C5 | 539 | 481 | 16,127 | 17,248 | 0 | 171 | 248 | 473 | 16,565 | 454 | 32,668 | 17,010 | 34,962 | 15,710 | 17,024 | 16,956 | 16,370 | 300 | 16,651 | 17,022 |

| BWH-C6 | 400 | 344 | 16,094 | 17,202 | 171 | 0 | 113 | 338 | 16,509 | 333 | 32,662 | 16,956 | 34,964 | 15,666 | 16,984 | 16,924 | 16,324 | 161 | 16,619 | 16,982 |

| BWH-C7 | 349 | 293 | 16,093 | 17,207 | 248 | 113 | 0 | 289 | 16,496 | 284 | 32,687 | 16,951 | 34,987 | 15,665 | 16,998 | 16,937 | 16,326 | 108 | 16,618 | 16,996 |

| BWH-C8 | 612 | 556 | 16,064 | 17,176 | 473 | 338 | 289 | 0 | 16,484 | 35 | 32,553 | 16,946 | 34,845 | 15,638 | 16,957 | 16,887 | 16,257 | 345 | 16,603 | 16,955 |

| BWH-C9 | 16,533 | 16,533 | 16,311 | 16,659 | 16,565 | 16,509 | 16,496 | 16,484 | 0 | 16,485 | 32,741 | 16,719 | 35,206 | 16,195 | 16,655 | 16,699 | 15,817 | 16,530 | 14,805 | 16,653 |

| BWH-C10 | 601 | 549 | 16,047 | 17,162 | 454 | 333 | 284 | 35 | 16,485 | 0 | 32,543 | 16,931 | 34,834 | 15,623 | 16,956 | 16,872 | 16,240 | 336 | 16,590 | 16,954 |

| BWH-NC1 | 32,692 | 32,713 | 32,209 | 33,115 | 32,668 | 32,662 | 32,687 | 32,553 | 32,741 | 32,543 | 0 | 33,169 | 12,703 | 32,160 | 32,978 | 32,915 | 32,507 | 32,719 | 32,945 | 32,976 |

| BWH-NC2 | 17,009 | 17,008 | 16,632 | 16,965 | 17,010 | 16,956 | 16,951 | 16,946 | 16,719 | 16,931 | 33,169 | 0 | 35,586 | 16,830 | 16,460 | 16,793 | 16,740 | 16,983 | 17,063 | 16,458 |

| BWH-NC5 | 34,958 | 34,977 | 34,566 | 35,520 | 34,962 | 34,964 | 34,987 | 34,845 | 35,206 | 34,834 | 12,703 | 35,586 | 0 | 34,488 | 35,348 | 35,331 | 34,808 | 35,011 | 35,228 | 35,346 |

| BWH-NC6 | 15,714 | 15,698 | 16,913 | 16,860 | 15,710 | 15,666 | 15,665 | 15,638 | 16,195 | 15,623 | 32,160 | 16,830 | 34,488 | 0 | 16,845 | 16,729 | 16,112 | 15,697 | 16,457 | 16,843 |

| BWH-NC7 | 17,001 | 16,998 | 16,915 | 16,290 | 17,024 | 16,984 | 16,998 | 16,957 | 16,655 | 16,956 | 32,978 | 16,460 | 35,348 | 16,845 | 0 | 16,434 | 16,764 | 17,022 | 16,692 | 8 |

| BWH-NC9 | 16,961 | 16,961 | 16,813 | 16,770 | 16,956 | 16,924 | 16,937 | 16,887 | 16,699 | 16,872 | 32,915 | 16,793 | 35,331 | 16,729 | 16,434 | 0 | 16,716 | 16,973 | 16,866 | 16,432 |

| BWH-NC10 | 16,359 | 16,358 | 16,388 | 16,937 | 16,370 | 16,324 | 16,326 | 16,257 | 15,817 | 16,240 | 32,507 | 16,740 | 34,808 | 16,112 | 16,764 | 16,716 | 0 | 16,359 | 16,297 | 16,762 |

| BWH-NC12 | 373 | 321 | 16,135 | 17,241 | 300 | 161 | 108 | 345 | 16,530 | 336 | 32,719 | 16,983 | 35,011 | 15,697 | 17,022 | 16,973 | 16,359 | 0 | 16,656 | 17,020 |

| BWH-NC13 | 16,671 | 16,673 | 16,245 | 17,094 | 16,651 | 16,619 | 16,618 | 16,603 | 14,805 | 16,590 | 32,945 | 17,063 | 35,228 | 16,457 | 16,692 | 16,866 | 16,297 | 16,656 | 0 | 16,690 |

| BWH-NC36 | 16,999 | 16,996 | 15,814 | 16,288 | 17,022 | 16,982 | 16,996 | 16,955 | 16,653 | 16,954 | 32,976 | 16,458 | 35,346 | 16,843 | 8 | 16,432 | 16,762 | 17,020 | 16,690 | 0 |

Clinical isolates of E. cloacae also belonged to a variety of MLSTs (Fig. 4), with the most common being ST78 (n = 6), in addition to ST171 (n = 3), ST190 (n = 3), ST252 (n = 1), ST162 (n = 1), ST133 (n = 1), and unknown MLST types (n = 6). Carbapenemase-harboring strains belonged to ST78 and ST171. Non-carbapenemase-carrying strains within ST78 included BWH-NC16 and BWH-NC28. The former was resistant to ertapenem but susceptible to imipenem and meropenem. This strain had a chromosomal AmpC gene, as well as a deletion in the C-terminal-domain region of the AmpD gene, which is associated with a carbapenem-resistant phenotype (16). BWH-NC28 was panresistant but was carbapenemase gene negative. It carried the CTX-M-15 ESBL gene in addition to the chromosomal AmpC gene, which in combination have been reported to cause phenotypic resistance to ertapenem (27). A disrupted porin (OmpF) likely also contributed to this isolate’s highly resistant phenotype (see Table S4 in the supplemental material).

The Enterobacter cloacae isolates demonstrated less overall SNP diversity than the Klebsiella strains, with a range of 0 to 14,550 SNPs among strains (Table 3). Isolates within the ST78 group of strains differed by 6 to 19 SNPs. Two sets of two strains carried a KPC-4 gene on the same mobile element; these were strains BWH-C16 and -C17 (pBWH-C16-KPC) and strains BWH-C11 and -C12 (ME-BWH-C11-KPC). Chromosomal SNP analyses showed them to be separated by 9 and 6 SNPs, respectively, making them the most similar pairs within the ST78 group. Among the ST171 group, strains BWH-C13, -C14, and -C15 were virtually identical (0 to 1 SNPs) and carried a KPC-4 gene on mobile element pBWH-C14-KPC (Fig. 4).

TABLE 3 .

SNP matrix for Enterobacter cloacae isolates

| Strain | No. of SNPs that differ between indicated strains |

||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BWH-C11 | BWH-C12 | BWH-C13 | BWH-C14 | BWH-C15 | BWH-C16 | BWH-C17 | BWH-NC14 | BWH-NC15 | BWH-NC16 | BWH-NC17 | BWH-NC18 | BWH-NC19 | BWH-NC20 | BWH-NC21 | BWH-NC22 | BWH-NC24 | BWH-NC25 | BWH-NC26 | BWH-NC28 | BWH-NC37 | |

| BWH-C11 | 0 | 9 | 5885 | 5886 | 5886 | 11 | 11 | 13,987 | 5862 | 14 | 5799 | 5798 | 14,288 | 5818 | 5775 | 13,916 | 5823 | 5803 | 5798 | 14 | 14,289 |

| BWH-C12 | 9 | 0 | 5885 | 5886 | 5886 | 16 | 16 | 13,991 | 5862 | 19 | 5802 | 5801 | 14,290 | 5822 | 5779 | 13,920 | 5827 | 5807 | 5801 | 19 | 14,291 |

| BWH-C13 | 5885 | 5885 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 5884 | 5884 | 13,873 | 1625 | 5883 | 4621 | 4620 | 14,234 | 4562 | 4564 | 13,721 | 4615 | 4601 | 4622 | 5879 | 14,231 |

| BWH-C14 | 5886 | 5886 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5885 | 5885 | 13,872 | 1626 | 5884 | 4622 | 4621 | 14,235 | 4563 | 4565 | 13,720 | 4616 | 4602 | 4623 | 5880 | 14,232 |

| BWH-C15 | 5886 | 5886 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5885 | 5885 | 13,872 | 1626 | 5884 | 4622 | 4621 | 14,235 | 4563 | 4565 | 13,720 | 4616 | 4602 | 4623 | 5880 | 14,232 |

| BWH-C16 | 11 | 16 | 5884 | 5885 | 5885 | 0 | 6 | 13,990 | 5865 | 13 | 5800 | 5799 | 14,292 | 5819 | 5774 | 13,919 | 5822 | 5804 | 5799 | 13 | 14,295 |

| BWH-C17 | 11 | 16 | 5884 | 5885 | 5885 | 6 | 0 | 13,988 | 5865 | 13 | 5798 | 5797 | 14,290 | 5819 | 5774 | 13,917 | 5822 | 5802 | 5797 | 13 | 14,293 |

| BWH-NC14 | 13,987 | 13,991 | 13,873 | 13,872 | 13,872 | 13,990 | 13,988 | 0 | 13,828 | 13,987 | 13,989 | 13,988 | 14,104 | 14,023 | 14,014 | 10,540 | 14,069 | 13,947 | 13,987 | 13,991 | 14,213 |

| BWH-NC15 | 5862 | 5862 | 1625 | 1626 | 1626 | 5865 | 5865 | 13,828 | 0 | 5860 | 4548 | 4547 | 14,250 | 4506 | 4511 | 13,686 | 4568 | 4525 | 4548 | 5858 | 14,223 |

| BWH-NC16 | 14 | 19 | 5883 | 5884 | 5884 | 13 | 13 | 13,987 | 5860 | 0 | 5799 | 5798 | 14,288 | 5822 | 5775 | 13,916 | 5823 | 5801 | 5798 | 14 | 14,289 |

| BWH-NC17 | 5799 | 5802 | 4621 | 4622 | 4622 | 5800 | 5798 | 13,989 | 4548 | 5799 | 0 | 1 | 14,312 | 1735 | 1770 | 13,972 | 1813 | 1935 | 31 | 5797 | 14,291 |

| BWH-NC18 | 5798 | 5801 | 4620 | 4621 | 4621 | 5799 | 5797 | 13,988 | 4547 | 5798 | 1 | 0 | 14,313 | 1736 | 1771 | 13,971 | 1814 | 1936 | 32 | 5796 | 14,292 |

| BWH-NC19 | 14,288 | 14,290 | 14,234 | 14,235 | 14,235 | 14,292 | 14,290 | 14,104 | 14,250 | 14,288 | 14,312 | 14,313 | 0 | 14,298 | 14,329 | 14,234 | 14,380 | 14,257 | 14,308 | 14,288 | 5062 |

| BWH-NC20 | 5818 | 5822 | 4562 | 4563 | 4563 | 5819 | 5819 | 14,023 | 4506 | 5822 | 1735 | 1736 | 14,298 | 0 | 1851 | 13,971 | 1895 | 1922 | 1738 | 5818 | 14,258 |

| BWH-NC21 | 5775 | 5779 | 4564 | 4565 | 4565 | 5774 | 5774 | 14,014 | 4511 | 5775 | 1770 | 1771 | 14,329 | 1851 | 0 | 13,987 | 79 | 1984 | 1771 | 5771 | 14,289 |

| BWH-NC22 | 13,916 | 13,920 | 13,721 | 13,720 | 13,720 | 13,919 | 13,917 | 10,540 | 13,686 | 13,916 | 13,972 | 13,971 | 14,234 | 13,971 | 13,987 | 0 | 14,037 | 13,898 | 13,970 | 13,916 | 14,361 |

| BWH-NC24 | 5823 | 5827 | 4615 | 4616 | 4616 | 5822 | 5822 | 14,069 | 4568 | 5823 | 1813 | 1814 | 14,380 | 1895 | 79 | 14,037 | 0 | 2028 | 1814 | 5819 | 14,337 |

| BWH-NC25 | 5803 | 5807 | 4601 | 4602 | 4602 | 5804 | 5802 | 13,947 | 4525 | 5801 | 1935 | 1936 | 14,257 | 1922 | 1984 | 13,898 | 2028 | 0 | 1934 | 5801 | 14,232 |

| BWH-NC26 | 5798 | 5801 | 4622 | 4623 | 4623 | 5799 | 5797 | 13,987 | 4548 | 5798 | 31 | 32 | 14,308 | 1738 | 1771 | 13,970 | 1814 | 1934 | 0 | 5796 | 14,288 |

| BWH-NC28 | 14 | 19 | 5879 | 5880 | 5880 | 13 | 13 | 13,991 | 5858 | 14 | 5797 | 5796 | 14,288 | 5818 | 5771 | 13,916 | 5819 | 5801 | 5796 | 0 | 14,291 |

| BWH-NC37 | 14,289 | 14,291 | 14,231 | 14,232 | 14,232 | 14,295 | 14,293 | 14,213 | 14,223 | 14,289 | 14,291 | 14,292 | 5062 | 14,258 | 14,289 | 14,361 | 14,337 | 14,232 | 14,288 | 14,291 | 0 |

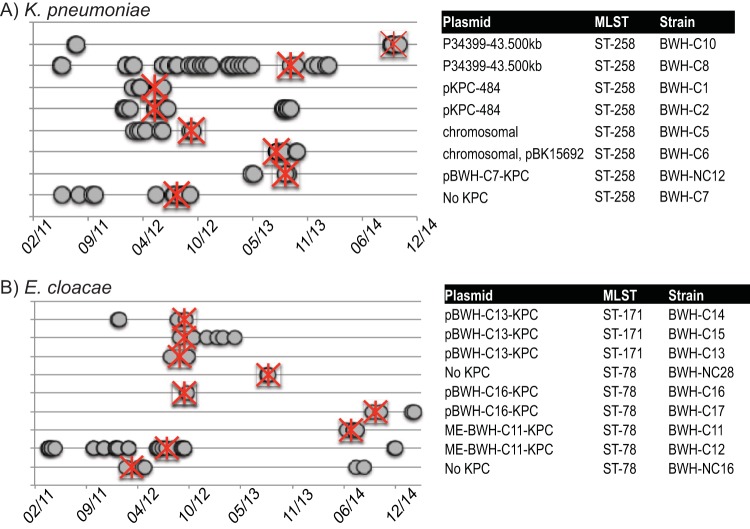

Epidemiological detection of strain entry and outbreaks.

Patient diagnoses, lengths of inpatient stays, locations within the hospital, and coisolates cultured over the 3-year period of analyses were collected for all patients (Fig. 5). The analyses identified limited outbreaks within the hospital but, more prominently, noted sporadic detection of strains with identical plasmids months to more than a year apart. In the latter cases, a common hospital-based reservoir could not be identified. The most closely linked isolates in this cohort, BWH-C13, -C14, and -C15, differed by 0 or 1 SNP and were collected within 18 days of each other from patients being treated by the same clinical service.

FIG 5 .

Integrating genomics with patient metadata. All members of each MLST with more than one representative (including at least one carbapenemase producer) were associated with patient metadata (dates of inpatient stays, diagnoses, and providers). Admissions and discharges are denoted by grey circles linked by thick lines (not visible for short stays). Dates of first positive CRE cultures are indicated by red asterisks. Associated carbapenemase gene-bearing plasmids are indicated to the right. Isolates of K. pneumoniae ST258 (A) and E. cloacae ST171 and ST78 (B) are shown.

DISCUSSION

Several studies have shown the utility of clinical microbial genome sequencing to aid in outbreak detection and the tracking of virulence and resistance factors (28, 29). We used genome sequencing to identify the genetic determinants of carbapenem resistance and their context within mobile elements or chromosomal sequences. In this manner, a hospital-specific repository of resistance genes, transposons, and mobile elements enabled more refined and rapid analyses of new isolates as they occurred (see Fig. S3 in the supplemental material).

Among the K. pneumoniae isolates, phenotypic resistance to carbapenems was mediated by KPC-2, -3, and -4 and OXA-48, as well as other beta-lactamases, in conjunction with accessory proteins, such as porins. OXA-48 has only recently been reported in the United States (30). In contrast, carbapenemase-producing E. cloacae strains harbored only KPC-4, which has been reported uncommonly in other CRE surveys (10, 12, 14, 31, 32). Non-carbapenemase-carrying isolates of E. cloacae with phenotypic carbapenem resistance carried ESBL genes and/or mutated AmpD and porin genes.

Klebsiella KPC genes were carried on different isoforms of Tn4401, a, b, and e, which were further inserted into seven different plasmids and, in two instances, chromosomally. We identified several known KPC-encoding constructs, such as pKPC-484, pBK15692, p34399-43.500kbp, and E71T.

pKPC-484 (Tn4401a::blaKPC-2) (10) and p34399-43.500kb (Tn4401b::blaKPC-3) were each identified in two patients with no obvious epidemiological connections. The IncI plasmid pBK15692, first identified in a K. pneumoniae strain isolated in 2005 in a New Jersey hospital, carries a KPC-3 gene within Tn4401b that has inserted into Tn1331 (22). Strain BWH-C6, which has a chromosomal Tn4401b, carries the pBK15692 plasmid with an additional copy of Tn4401b and a small deletion in Tn1331, removing the aad and blaOXA-9 genes. Interestingly, strain BWH-C5, with an identical chromosomal Tn4401b, carries the pBK15692 backbone with Tn4401b apparently excised. The only OXA-48 carbapenemase gene identified in this study was carried by plasmid E71T, an IncL/M plasmid first described in Ireland (21).

Novel plasmids identified in Klebsiella isolates included pBWH-C3-KPC, which carried the only KPC-4 gene identified in Klebsiella and showed the closest identity (75%) to pBK31551, a KPC-4 gene-bearing IncN plasmid that was first detected in New Jersey (23). In addition, plasmid pBWH-C7-KPC carried a Tn4401e insertion in the backbone of the IncA/C plasmid PR55, along with a large bacteriophage (24).

Plasmid analyses further refined the groupings among the KPC-carrying Enterobacter strains, identifying three distinct groups with pBWH-C13-KPC, pBWH-C16-KPC, or ME-BWH-C11-KPC. The backbone of the KPC-4 gene-carrying plasmid pBWH-C13-KPC showed 91% identity to the IncH12A/IncH12 plasmid pK29 (26). This construct occurred in the most closely related strains (0 to 1 SNPs), isolated within 18 days of each other from patients receiving care from the same inpatient service but housed on different floors of the hospital.

Notably, the other two Enterobacter carbapenemase gene-bearing elements, (pBWH-C16-KPC and, ME-BWH-C11-KPC), along with Klebsiella plasmid pBWH-C3-KPC, share homology with the IncN plasmid pBK31551, illustrating its capacity to transmit KPC-4 across species. We suggest one possible scenario linking the pBK31551-related constructs across species (see Fig. S4 in the supplemental material), namely, hospital entry within a K. pneumoniae ST834 or ST113 strain and spread to E. cloacae ST78 strains at a time prior to the start of genomic surveillance in 2011. The pBWH-C3-KPC construct in Klebsiella and the ME-BWH-C11-KPC and pBWH-C16-KPC derivatives in Enterobacter were then detected the following year.

Plasmid analyses among the K. pneumoniae MLST types further refined strain relationships. In particular, the relatively low number of SNPs among isolates carrying identical plasmids suggests the spread of clonal strains with their plasmids over the 3-year period, rather than significant transfer of plasmids to other strains. In contrast to Klebsiella, relatively little is known about the prevalence of KPC carriage among Enterobacter MLSTs, though an MLST scheme has recently been described for E. cloacae (33–35). These studies illustrated the multiclonal nature of drug-resistant Enterobacter strains by finding KPC-4 carriage in ST78 and ST171.

These results demonstrate the importance of analyzing resistance-carrying transposons and plasmids to enrich epidemiological tracking of resistance determinants within and across institutions. Among CRE strains from the same ST type that shared chromosomal SNP profiles, plasmid analyses improved the subclassification of strains and their nature as sporadic or associated with a potential internal outbreak or reservoir. The transposon, plasmid, and chromosomal SNP profiles further enabled the development of a hospital-specific repository of chromosomes and mobile elements that could additionally contribute to national surveillance efforts, which will be needed to more effectively identify and track resistance determinants across institutions.

Our data also highlight the strengths and weaknesses of short-read sequencing platforms to analyze mobile genetic elements with highly repetitive sequences. Currently, long-read sequencing technology remains beyond the capacity of most clinical microbiology laboratories. Closed reference-quality plasmid sequences are rarely obtained with short-read sequencing alone. However, assembled contigs from short-read platforms can be used to readily identify specific resistance genes and their immediate genomic context. The growing plasmid reference content in public databases further enhances the capacity to generate clinically valuable draft plasmid maps using short-read platforms. As more clinical laboratories move to perform such analyses, it will be possible to undertake more robust analyses of strain and mobile element transmission of drug resistance by institution, region, and timeframe, as well as in environments external to health care systems.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains and data.

All strains and data were collected under IRB protocol 2011-P-002883 approved by the Partners Healthcare Internal Review Board. Strains were collected from the Clinical Microbiology Laboratory at Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH), a 793-bed hospital in Boston, MA, that supports a number of inpatient and outpatient services. Standing queries in the Crimson LIMS (36) flagged resistance to ertapenem, meropenem, and/or imipenem among members of the Enterobacteriaceae identified during routine clinical microbiologic testing. Thirty-seven isolates of carbapenem-nonsusceptible Klebsiella pneumoniae and Enterobacter cloacae, along with four pansusceptible and ESBL strains, were collected from October 2011 to October 2014 and included in genomic analyses. Phenotypic resistance was determined by MIC (Vitek 2 platform), Kirby-Bauer disk diffusion, and/or E-test strips (bioMérieux, Crapone, France) (37). Total DNA was isolated from each strain on the Qiagen EZ1 platform using the tissue DNA isolation kit (Qiagen, Venlo, Netherlands). Phenotypic resistance at BWH was tracked and charted using WHOnet (38). Patient data were analyzed in the hospital electronic medical records (EMR).

KPC PCR.

KPC genes were amplified according to the method of Mathers et al. (39).

Library preparation and sequencing.

Libraries were prepared using the Nextera XT system (Illumina, San Diego, CA). Strains were sequenced on the MiSeq platform (Illumina), using the V1 (150-bp paired-end reads) or V3 (300-bp paired-end reads) kit. The average sequencing depth resulted in 103× coverage.

Contig assembly and analysis.

De novo assembly was performed using SPAdes (version 3.1) (40), and the resulting contigs were assessed with QUAST (41), which showed an average N50 of 273,646 bp across isolates. Resistance genes were identified by BLAST against a database of resistance genes compiled from the Comprehensive Antibiotic Resistance Database (CARD), the Lahey Clinic (http://www.lahey.org/studies), and the Lactamase Engineering database (http://www.laced.uni-stuttgart.de) (42). The criteria used to positively call specific classes of beta-lactamases were (i) coverage of >97% query length of the putative gene, (ii) >97% identity with the matching reference sequence, and (iii) <5 mismatches, as well as no gaps in the alignment. To determine chromosomal versus mobile genomic context of the beta-lactamases discovered, the surrounding sequence neighborhoods on the parent contigs that contained beta-lactamase gene(s) were compared to the GenBank nt database using BLAST to assess matches to reference plasmids or chromosomes.

Transposon carriage was assessed by using BLAST to compare the de novo contigs against a set of transposon sequences derived from GenBank. To assess transposon terminal direct repeats (TDRs), copy numbers, and insertion sites, Bowtie2 was used to align raw reads to transposon junctions, which were grouped by the 5-bp TDR generated by the transposon (43). Five-base-pair TDRs that had a matching TDR on both the 5′ and 3′ end of the transposon were considered to be the borders of a complete transposon. The nontransposon sequence adjoining the TDR was compared to the GenBank nt database using BLAST in order to confirm the insertion site.

Plasmid incompatibility (Inc) groups were assessed using BLAST and the PlasmidFinder database from the Center for Genomic Epidemiology (CGE) (44). To identify all plasmid-associated contigs in an isolate, a BLAST search was conducted against the NCBI bacterial plasmid database (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov). Contigs that demonstrated a likely plasmid origin were selected and then compared to the GenBank nt database using BLAST for a more accurate identification and to arrive at a list of candidate plasmids, which were classified according to the plasmid replicons. To assess the strength of plasmid identifications and analyze antibiotic resistance regions, raw reads were aligned to plasmid reference sequences using Bowtie (45). Plasmids with the highest coverage by raw reads, where at least 65% of the backbone was accounted for, were selected as the best matches. To ascertain whether isolates contained regions not present in the reference plasmid, de novo contigs generated in SPAdes were ordered to the sequence of the reference plasmid using the MAUVE aligner and novel regions identified (46). Plasmid maps were then generated from each set of ordered contigs, annotated using the RAST engine, and given a new plasmid name if they were <98% identical to the reference construct or included novel insertions not present in the reference sequence (i.e., Tn4401) (47, 48). Carbapenemase-containing elements which could not be placed in a plasmid backbone were denoted as “ME,” for mobile element. Maps were visualized with MacVector software (MacVector, Inc., Cary, NC).

Chromosomal analyses of resistance genes and modifying mutations.

Genes involved in the regulation of AmpC (ampD and ampR), as well as the porin genes ompC and ompF (ompK36 and ompK35 in Klebsiella strains), were assessed for premature stop codons, disruptive insertion sequences (IS), and nonsynonymous mutations known to affect enzyme function (7, 15–19).

MLST.

Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) was done by using the MLST finder tool at the Center for Genetic Epidemiology (49).

SNP typing.

Chromosomal single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) across sequenced isolates were called in de novo-assembled contigs using the Nucmer and showSNPs tools in the Mummer package (50). Calls were made in comparison to chromosomal sequences from reference strains K. pneumoniae KP_MGH_78578 (NC_009648) and E. cloacae ENHKU01 (NC_018405). Default settings were used for Nucmer, and the “-CIlrT” options were used with showSNPs. Additional filtering steps applied to SNP calls were as follows: (i) removal of SNPs mapping within genes associated with bacteriophage or other mobile elements, (ii) removal of all SNPs within 20 bp of another SNP, (iii) removal of all SNPs within 20 bp of the end of a contig, (iv) removal of SNPs from noncoding regions, and (v) removal of SNPs from any region with greater than 2× the depth of coverage of the strain average. Concatenated SNPs were used to construct phylogenetic trees using the approximate-maximum-likelihood-based approach in FastTree with parameters “-nt -gtr” (51). Trees were visualized in FigTree using the midpoint-branching tree-building option (http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/figtree/). Local support values for each of the nodes were calculated in FastTree.

Sequence data accession numbers.

Accession numbers for draft sequence files (raw reads) are in Table S5 in the supplemental material. Reference plasmid sequences were downloaded from ftp://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genomes/Plasmids/. Reference transposon sequences used in this study are available at http://metagenomics.partners.org/PathogenGenomes/.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Novel carbapenemase-carrying plasmids identified in this study. Maps of ordered de novo contigs of carbapenemase plasmids with <98% identity to reference plasmids and/or novel insertions not present in reference plasmids. Boundaries of de novo contigs are shown in red, Tn4401 in green, and genes annotated by RAST in blue. Constructs include pBWH-C3-KPC (A), pBWH-C7-KPC (B), pBWH-C9-KPC (C), pBWH-C13-KPC (D), and pBWH-C16-KPC (E). Download

Chromosomal Tn4401 insertions. BWH-C5 and BWH-C6 both have chromosomal copies of Tn4401 (green), while BWH-C6 has an additional copy on plasmid pBK15692 (green). (A) One set of TDRs was found in BWH-C5 (TTTAA), corresponding to the chromosomal Tn4401. (B) Two sets of TDRs were found in BWH-C6, one for the chromosomal Tn4401 (TTTAA) and one for the plasmid copy in pBK15692 (GTTCT). (A) In BWH-C5, alignment of raw reads to the pBK15692 reference demonstrates deep coverage over the pBK15692 backbone but low/no coverage over Tn4401 except for a low number of reads mapping to the central portion of the transposon likely derived from the chromosomal copy (only Tn4401 flanking regions, including the right- and left-end inverted repeats [IRR and IRL], are shown). (B) In contrast, the entire pBK15692 sequence is covered by raw reads at an even depth in BWH-C6 (including Tn4401). Download

Workflow for whole-genome sequencing of carbapenem-resistant isolates. Intrainstitutional data analysis, storage, and reporting starts with automated detection of strains to be sequenced, based on their phenotypic resistance profiles. After isolation of genomic DNA, library preparation, and sequencing, the bioinformatics pipeline performs quality control assessments, de novo contig generation, antibiotic gene and transposon identification, preliminary plasmid assignment, and attachment of patient metadata. Outside resources are used to develop content for mobile element analyses. Manual review finalizes the plasmid assignment and epidemiological tracking of strains and plasmids to generate a strain “report card” for hospital infection control. This report defines resistance-carrying strains by the distance tree of chromosomal SNPs of current and prior isolates of interest that further incorporates the resistance genes identified and their carriage on transposon and plasmid mobile elements. Download

Hypothetical scenario for spread of pBK31551-derived elements within a hospital. K. pneumoniae isolates of ST834 (red), ST113 (orange), and unknown STs (grey) and E. cloacae isolates of ST78 (blue) are shown. The plasmids that were observed are represented by solid lines, and hypothetical plasmids by dashed lines. pBK31551 was first detected in a K. pneumoniae ST834 strain isolated in a New Jersey hospital in 2005. pBWH-C3-KPC was observed at BWH in March 2012 in a K. pneumoniae ST113 strain. Subsequent derivatives of pBK31551 were found in E. cloacae ST78 strains in July 2012 and September 2012. Download

Strain descriptions with patient characteristics.

Beta-lactamases and phenotypic resistance in carbapenemase-producing clinical isolates.

Beta-lactamases and phenotypic resistance in non-carbapenemase-producing clinical isolates.

Mutations in AmpD, AmpR, OmpC (OmpK36), and OmpF (OmpK35).

Strain fastq files loaded into the NIH Short Read Archive (SRA).

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by a grant from Brigham and Women’s Hospital Clinical Laboratories, the Center for Clinical and Translational Metagenomics, NIH grants R01 LM010100 (L. Bry) and P30 DK34854 (CCTM), and the U.S. FDA CFSAN (M. Allard).

We thank Georg Gerber, Debbie Yokoe, and Milenko Tanasijevic for their suggestions and recommendations for infection control support, Michael Feldgarden at NCBI for updated beta-lactamase analyses, Mark Groner for assistance with data analysis, Socheat Men and Vera Belavusava with the BWH Specimen Bank collection of strains, and the staff of the Molecular Biology Core Facilities at the Dana Farber Cancer Institute.

Footnotes

Citation Pecora ND, Li N, Allard M, Li C, Albano E, Delaney M, Dubois A, Onderdonk AB, Bry L. 2015. Genomically informed surveillance for carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae in a health care system. mBio 6(4):e01030-15. doi:10.1128/mBio.01030-15.

REFERENCES

- 1.Falagas ME, Tansarli GS, Karageorgopoulos DE, Vardakas KZ. 2014. Deaths attributable to carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae infections. Emerg Infect Dis 20:1170–1175. doi: 10.3201/eid2007.121004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.WHO 2014. Antimicrobial resistance: global report on surveillance 2014. World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Queenan AM, Bush K. 2007. Carbapenemases: the versatile beta-lactamases. Clin Microbiol Rev 20:440–458. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00001-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Munoz-Price LS, Poirel L, Bonomo RA, Schwaber MJ, Daikos GL, Cormican M, Cornaglia G, Garau J, Gniadkowski M, Hayden MK, Kumarasamy K, Livermore DM, Maya JJ, Nordmann P, Patel JB, Paterson DL, Pitout J, Villegas MV, Wang H, Woodford N. 2013. Clinical epidemiology of the global expansion of Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemases. Lancet Infect Dis 13:785–796. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70190-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nordmann P, Dortet L, Poirel L. 2012. Carbapenem resistance in Enterobacteriaceae: here is the storm! Trends Mol Med 18:263–272. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacoby GA, Mills DM, Chow N. 2004. Role of beta-lactamases and porins in resistance to ertapenem and other beta-lactams in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 48:3203–3206. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.8.3203-3206.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kaneko K, Okamoto R, Nakano R, Kawakami S, Inoue M. 2005. Gene mutations responsible for overexpression of AmpC beta-lactamase in some clinical isolates of Enterobacter cloacae. J Clin Microbiol 43:2955–2958. doi: 10.1128/JCM.43.6.2955-2958.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen L, Mathema B, Chavda KD, DeLeo FR, Bonomo RA, Kreiswirth BN. 2014. Carbapenemase-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae: molecular and genetic decoding. Trends Microbiol 22:686–696. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2014.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Conlan S, Deming C, Tsai YC, Lau AF, Dekker JP, Korlach J, Segre JA. 2014. Complete genome sequence of a Klebsiella pneumoniae isolate with chromosomally encoded carbapenem resistance and colibactin synthesis loci. Genome Announc 2(6):e01332-14. doi: 10.1128/genomeA.01332-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Conlan S, Thomas PJ, Deming C, Park M, Lau AF, Dekker JP, Snitkin ES, Clark TA, Luong K, Song Y, Tsai YC, Boitano M, Dayal J, Brooks SY, Schmidt B, Young AC, Thomas JW, Bouffard GG, Blakesley RW, NISC Comparative Sequencing Program . 2014. Single-molecule sequencing to track plasmid diversity of hospital-associated carbapenemase-producing Enterobacteriaceae. Sci Transl Med 6:254ra126. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.3009845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Poirel L, Potron A, Nordmann P. 2012. OXA-48-like carbapenemases: the phantom menace. J Antimicrob Chemother 67:1597–1606. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mathers AJ, Stoesser N, Sheppard AE, Pankhurst L, Giess A, Yeh AJ, Didelot X, Turner SD, Sebra R, Kasarskis A, Peto T, Crook D, Sifri CD. 2015. Klebsiella pneumoniae carbapenemase (KPC)-producing K. pneumoniae at a single institution: insights into endemicity from whole-genome sequencing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 59:1656–1663. doi: 10.1128/AAC.04292-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deleo FR, Chen L, Porcella SF, Martens CA, Kobayashi SD, Porter AR, Chavda KD, Jacobs MR, Mathema B, Olsen RJ, Bonomo RA, Musser JM, Kreiswirth BN. 2014. Molecular dissection of the evolution of carbapenem-resistant multilocus sequence type 258 Klebsiella pneumoniae. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:4988–4993. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321364111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wright MS, Perez F, Brinkac L, Jacobs MR, Kaye K, Cober E, van Duin D, Marshall SH, Hujer AM, Rudin SD, Hujer KM, Bonomo RA, Adams MD. 2014. Population structure of KPC-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae isolates from midwestern U.S. hospitals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:4961–4965. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00125-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Petrosino JF, Pendleton AR, Weiner JH, Rosenberg SM. 2002. Chromosomal system for studying AmpC-mediated beta-lactam resistance mutation in Escherichia coli. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 46:1535–1539. doi: 10.1128/AAC.46.5.1535-1539.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schmidtke AJ, Hanson ND. 2006. Model system to evaluate the effect of ampD mutations on AmpC-mediated beta-lactam resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 50:2030–2037. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01458-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clancy CJ, Chen L, Hong JH, Cheng S, Hao B, Shields RK, Farrell AN, Doi Y, Zhao Y, Perlin DS, Kreiswirth BN, Nguyen MH. 2013. Mutations of the ompK36 porin gene and promoter impact responses of sequence type 258, KPC-2-producing Klebsiella pneumoniae strains to doripenem and doripenem-colistin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:5258–5265. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01069-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Doumith M, Ellington MJ, Livermore DM, Woodford N. 2009. Molecular mechanisms disrupting porin expression in ertapenem-resistant Klebsiella and Enterobacter spp. clinical isolates from the UK. J Antimicrob Chemother 63:659–667. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkp029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kuga A, Okamoto R, Inoue M. 2000. ampR gene mutations that greatly increase class C beta-lactamase activity in Enterobacter cloacae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 44:561–567. doi: 10.1128/AAC.44.3.561-567.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Glupczynski Y, Huang TD, Bouchahrouf W, Rezende de Castro R, Bauraing C, Gérard M, Verbruggen AM, Deplano A, Denis O, Bogaerts P. 2012. Rapid emergence and spread of OXA-48-producing carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae isolates in Belgian hospitals. Int J Antimicrob Agents 39:168–172. doi: 10.1016/j.ijantimicag.2011.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Power K, Wang J, Karczmarczyk M, Crowley B, Cotter M, Haughton P, Lynch M, Schaffer K, Fanning S. 2014. Molecular analysis of OXA-48-carrying conjugative IncL/M-like plasmids in clinical isolates of Klebsiella pneumoniae in Ireland. Microb Drug Resist 20:270–274. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2013.0022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen L, Chavda KD, Al Laham N, Melano RG, Jacobs MR, Bonomo RA, Kreiswirth BN. 2013. Complete nucleotide sequence of a blaKPC-harboring IncI2 plasmid and its dissemination in New Jersey and New York hospitals. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:5019–5025. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01397-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen L, Chavda KD, Fraimow HS, Mediavilla JR, Melano RG, Jacobs MR, Bonomo RA, Kreiswirth BN. 2013. Complete nucleotide sequences of blaKPC-4- and blaKPC-5-harboring IncN and IncX plasmids from Klebsiella pneumoniae strains isolated in New Jersey. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:269–276. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01648-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Doublet B, Boyd D, Douard G, Praud K, Cloeckaert A, Mulvey MR. 2012. Complete nucleotide sequence of the multidrug resistance IncA/C plasmid pR55 from Klebsiella pneumoniae isolated in 1969. J Antimicrob Chemother 67:2354–2360. doi: 10.1093/jac/dks251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.García-Fernández A, Villa L, Carta C, Venditti C, Giordano A, Venditti M, Mancini C, Carattoli A. 2012. Klebsiella pneumoniae ST258 producing KPC-3 identified in Italy carries novel plasmids and OmpK36/OmpK35 porin variants. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 56:2143–2145. doi: 10.1128/AAC.05308-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chen YT, Chen YT, Lauderdale TL, Liao TL, Shiau YR, Shu HY, Wu KM, Yan JJ, Su IJ, Tsai SF. 2007. Sequencing and comparative genomic analysis of pK29, a 269-kilobase conjugative plasmid encoding CMY-8 and CTX-M-3 beta-lactamases in Klebsiella pneumoniae. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 51:3004–3007. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00167-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sheng WH, Badal RE, Hsueh PR, SMART Program . 2013. Distribution of extended-spectrum beta-lactamases, AmpC beta-lactamases, and carbapenemases among Enterobacteriaceae isolates causing intra-abdominal infections in the Asia-Pacific region: results of the study for monitoring antimicrobial resistance trends (SMART). Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:2981–2988. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00971-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Köser CU, Ellington MJ, Cartwright EJ, Gillespie SH, Brown NM, Farrington M, Holden MT, Dougan G, Bentley SD, Parkhill J, Peacock SJ. 2012. Routine use of microbial whole genome sequencing in diagnostic and public health microbiology. PLoS Pathog 8(8):e1002824. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002824. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Robilotti E, Kamboj M. 2015. Integration of whole-genome sequencing into infection control practices: the potential and the hurdles. J Clin Microbiol 53:1054–1055. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00349-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mathers AJ, Hazen KC, Carroll J, Yeh AJ, Cox HL, Bonomo RA, Sifri CD. 2013. First clinical cases of OXA-48-producing carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae in the United States: the “menace” arrives in the new world. J Clin Microbiol 51:680–683. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02580-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Van Duin D, Perez F, Rudin SD, Cober E, Hanrahan J, Ziegler J, Webber R, Fox J, Mason P, Richter SS, Cline M, Hall GS, Kaye KS, Jacobs MR, Kalayjian RC, Salata RA, Segre JA, Conlan S, Evans S, Fowler VG. 2014. Surveillance of carbapenem-resistant Klebsiella pneumoniae: tracking molecular epidemiology and outcomes through a regional network. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:4035–4041. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02636-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pollett S, Miller S, Hindler J, Uslan D, Carvalho M, Humphries RM. 2014. Phenotypic and molecular characteristics of carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae in a health care system in Los Angeles, California, from 2011 to 2013. J Clin Microbiol 52:4003–4009. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01397-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Girlich D, Poirel L, Nordmann P. 2015. Clonal distribution of multidrug-resistant Enterobacter cloacae. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 81:264–268. doi: 10.1016/j.diagmicrobio.2015.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Izdebski R, Baraniak A, Herda M, Fiett J, Bonten MJ, Carmeli Y, Goossens H, Hryniewicz W, Brun-Buisson C, Gniadkowski M, MOSAR WP2, WP3 and WP5 Study Groups . 2015. MLST reveals potentially high-risk international clones of Enterobacter cloacae. J Antimicrob Chemother 70:48–56. doi: 10.1093/jac/dku359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miyoshi-Akiyama T, Hayakawa K, Ohmagari N, Shimojima M, Kirikae T. 2013. Multilocus sequence typing (MLST) for characterization of Enterobacter cloacae. PLoS One 8(6):e66358. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0066358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Murphy S, Churchill S, Bry L, Chueh H, Weiss S, Lazarus R, Zeng Q, Dubey A, Gainer V, Mendis M, Glaser J, Kohane I. 2009. Instrumenting the health care enterprise for discovery research in the genomic era. Genome Res 19:1675–1681. doi: 10.1101/gr.094615.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.CLSI 2011. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing, 21st informational supplement. CLSI document M100-S21. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute, Wayne, PA. [Google Scholar]

- 38.O’Brien TF, Stelling JM. 1995. WHONET: an information system for monitoring antimicrobial resistance. Emerg Infect Dis 1:66. doi: 10.3201/eid0102.952009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mathers AJ, Cox HL, Kitchel B, Bonatti H, Brassinga AK, Carroll J, Scheld WM, Hazen KC, Sifri CD. 2011. Molecular dissection of an outbreak of carbapenem-resistant enterobacteriaceae reveals intergenus KPC carbapenemase transmission through a promiscuous plasmid. mBio 2(6):e00204–e00211. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00204-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bankevich A, Nurk S, Antipov D, Gurevich AA, Dvorkin M, Kulikov AS, Lesin VM, Nikolenko SI, Pham S, Prjibelski AD, Pyshkin AV, Sirotkin AV, Vyahhi N, Tesler G, Alekseyev MA, Pevzner PA. 2012. SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J Comput Biol 19:455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gurevich A, Saveliev V, Vyahhi N, Tesler G. 2013. QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 29:1072–1075. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McArthur AG, Waglechner N, Nizam F, Yan A, Azad MA, Baylay AJ, Bhullar K, Canova MJ, De Pascale G, Ejim L, Kalan L, King AM, Koteva K, Morar M, Mulvey MR, O’Brien JS, Pawlowski AC, Piddock LJ, Spanogiannopoulos P, Sutherland AD. 2013. The comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 57:3348–3357. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00419-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Langmead B, Salzberg SL. 2012. Fast gapped-read alignment with bowtie 2. Nat Methods 9:357–359. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Carattoli A, Zankari E, García-Fernández A, Voldby Larsen M, Lund O, Villa L, Møller Aarestrup F, Hasman H. 2014. In silico detection and typing of plasmids using PlasmidFinder and plasmid multilocus sequence typing. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 58:3895–3903. doi: 10.1128/AAC.02412-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Langmead B, Trapnell C, Pop M, Salzberg SL. 2009. Ultrafast and memory-efficient alignment of short DNA sequences to the human genome. Genome Biol 10(3):R25. doi: 10.1186/gb-2009-10-3-r25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Darling AE, Mau B, Perna NT. 2010. progressiveMauve: multiple genome alignment with gene gain, loss and rearrangement. PLoS One 5(6):e11147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aziz RK, Bartels D, Best AA, DeJongh M, Disz T, Edwards RA, Formsma K, Gerdes S, Glass EM, Kubal M, Meyer F, Olsen GJ, Olson R, Osterman AL, Overbeek RA, McNeil LK, Paarmann D, Paczian T, Parrello B, Pusch GD. 2008. The RAST server: rapid annotations using subsystems technology. BMC Genomics 9:75. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Overbeek R, Olson R, Pusch GD, Olsen GJ, Davis JJ, Disz T, Edwards RA, Gerdes S, Parrello B, Shukla M, Vonstein V, Wattam AR, Xia F, Stevens R. 2014. The SEED and the rapid annotation of microbial genomes using subsystems technology (RAST). Nucleic Acids Res 42:D206–D214. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Larsen MV, Cosentino S, Rasmussen S, Friis C, Hasman H, Marvig RL, Jelsbak L, Sicheritz-Pontén T, Ussery DW, Aarestrup FM, Lund O. 2012. Multilocus sequence typing of total-genome-sequenced bacteria. J Clin Microbiol 50:1355–1361. doi: 10.1128/JCM.06094-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kurtz S, Phillippy A, Delcher AL, Smoot M, Shumway M, Antonescu C, Salzberg SL. 2004. Versatile and open software for comparing large genomes. Genome Biol 5(2):R12. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-2-r12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Price MN, Dehal PS, Arkin AP. 2009. FastTree computing large minimum evolution trees with profiles instead of a distance matrix. Mol Biol Evol 26:1641–1650. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msp077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Novel carbapenemase-carrying plasmids identified in this study. Maps of ordered de novo contigs of carbapenemase plasmids with <98% identity to reference plasmids and/or novel insertions not present in reference plasmids. Boundaries of de novo contigs are shown in red, Tn4401 in green, and genes annotated by RAST in blue. Constructs include pBWH-C3-KPC (A), pBWH-C7-KPC (B), pBWH-C9-KPC (C), pBWH-C13-KPC (D), and pBWH-C16-KPC (E). Download

Chromosomal Tn4401 insertions. BWH-C5 and BWH-C6 both have chromosomal copies of Tn4401 (green), while BWH-C6 has an additional copy on plasmid pBK15692 (green). (A) One set of TDRs was found in BWH-C5 (TTTAA), corresponding to the chromosomal Tn4401. (B) Two sets of TDRs were found in BWH-C6, one for the chromosomal Tn4401 (TTTAA) and one for the plasmid copy in pBK15692 (GTTCT). (A) In BWH-C5, alignment of raw reads to the pBK15692 reference demonstrates deep coverage over the pBK15692 backbone but low/no coverage over Tn4401 except for a low number of reads mapping to the central portion of the transposon likely derived from the chromosomal copy (only Tn4401 flanking regions, including the right- and left-end inverted repeats [IRR and IRL], are shown). (B) In contrast, the entire pBK15692 sequence is covered by raw reads at an even depth in BWH-C6 (including Tn4401). Download

Workflow for whole-genome sequencing of carbapenem-resistant isolates. Intrainstitutional data analysis, storage, and reporting starts with automated detection of strains to be sequenced, based on their phenotypic resistance profiles. After isolation of genomic DNA, library preparation, and sequencing, the bioinformatics pipeline performs quality control assessments, de novo contig generation, antibiotic gene and transposon identification, preliminary plasmid assignment, and attachment of patient metadata. Outside resources are used to develop content for mobile element analyses. Manual review finalizes the plasmid assignment and epidemiological tracking of strains and plasmids to generate a strain “report card” for hospital infection control. This report defines resistance-carrying strains by the distance tree of chromosomal SNPs of current and prior isolates of interest that further incorporates the resistance genes identified and their carriage on transposon and plasmid mobile elements. Download

Hypothetical scenario for spread of pBK31551-derived elements within a hospital. K. pneumoniae isolates of ST834 (red), ST113 (orange), and unknown STs (grey) and E. cloacae isolates of ST78 (blue) are shown. The plasmids that were observed are represented by solid lines, and hypothetical plasmids by dashed lines. pBK31551 was first detected in a K. pneumoniae ST834 strain isolated in a New Jersey hospital in 2005. pBWH-C3-KPC was observed at BWH in March 2012 in a K. pneumoniae ST113 strain. Subsequent derivatives of pBK31551 were found in E. cloacae ST78 strains in July 2012 and September 2012. Download

Strain descriptions with patient characteristics.

Beta-lactamases and phenotypic resistance in carbapenemase-producing clinical isolates.

Beta-lactamases and phenotypic resistance in non-carbapenemase-producing clinical isolates.

Mutations in AmpD, AmpR, OmpC (OmpK36), and OmpF (OmpK35).

Strain fastq files loaded into the NIH Short Read Archive (SRA).