Abstract

Recently, induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs) have been generated in vivo from reprogrammable mice. These in vivo iPSCs display features of totipotency, i.e., they differentiate into the trophoblast lineage, as well as all 3 germ layers. Here, we developed a new reprogrammable mouse model carrying an Oct4-GFP reporter gene to facilitate the detection of reprogrammed pluripotent stem cells. Without doxycycline administration, some of the reprogrammable mice developed aggressively growing teratomas that contained Oct4-GFP+ cells. These teratoma-derived in vivo PSCs were morphologically indistinguishable from ESCs, expressed pluripotency markers, and could differentiate into tissues of all 3 germ layers. However, these in vivo reprogrammed PSCs were more similar to in vitro iPSCs than ESCs and did not contribute to the trophectoderm of the blastocysts after aggregation with 8-cell embryos. Therefore, the ability to differentiate into the trophoblast lineage might not be a unique characteristic of in vivo iPSCs.

Enforcing the expression of a specific combination of reprogramming factors such as Oct4, Sox2, Klf4, and c-Myc (OSKM) in somatic cells can result in the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs). These iPSCs express pluripotent stem cell markers and can differentiate into cells of all 3 germ layers and germ cells in vitro and in vivo. iPSCs have been suggested as a substitute for embryonic stem cells (ESCs) because of their similar differentiation potentials; moreover, iPSCs can be generated without sacrificing embryos. iPSCs can also be generated from diverse cell types, including extraembryonic1 and uniparental cell sources2. Although iPSCs are functionally very similar to ESCs, they are not identical and can be distinguished on the basis of global gene expression patterns3. Therefore, many researchers are constantly striving to generate iPSCs that more closely resemble ESCs. Non-viral reprogramming systems have been applied for iPSC generation, such as episomal introduction of DNA or RNA, protein delivery, and the sole use of small molecules4,5,6,7,8,9. High-quality naïve pluripotent iPSCs have been generated by cultivation in media supplemented with vitamin C or the 2-inhibitor (2i) culture condition (mitogen-activated protein kinase and glycogen synthase kinase 3 inhibitors)10,11,12.

Considerable progress has been made in direct reprogramming under in vitro culture conditions13. However, recent reports have suggested that the in vivo environment might serve as the niche for direct reprogramming. A series of studies have shown that the overexpression of fate-determining genes in vivo could reprogram resident cells or injected cells into other cell types, including neurons and neuroblasts14,15,16. Injection of plasmids encoding OSKM into the tail vein induced the upregulation of pluripotency-related genes in hepatocytes without subsequent teratoma formation17. iPSCs have also been generated in vivo from circulating blood cells of reprogrammable mice18,19. These in vivo iPSCs resemble ESCs more closely than iPSCs generated in vitro. Moreover, in vivo iPSCs differentiate into the trophectoderm lineage and all 3 germ layers, thereby demonstrating totipotency. However, differentiation into the trophoblast lineage is not characteristic of naïve pluripotent ESCs but is a primed pluripotency feature, as human ESCs preferentially differentiate into the trophoblast lineage20. These facts prompted us to address more characteristics from new in vivo iPSC lines. Here, we have developed a new method to generate in vivo iPSCs, which can be easily selected from reprogrammable mice. To facilitate the detection of reprogrammed cells, we generated a triple transgenic mouse carrying a transcriptional activator (rtTA; within the ubiquitously-expressed Rosa26 locus), a doxycycline-inducible polycistronic cassette encoding the 4 reprogramming factors (OSKM) within the Col1a1 locus, and Oct4-GFP. We obtained Oct4-GFP+ cells from teratomas of the reprogrammable mice. The reprogrammed PSCs were established from these teratoma-derived Oct4-GFP+ cells, which were morphologically indistinguishable from ESCs. However, these in vivo reprogrammed PSCs (rPSCs) were more similar to in vitro iPSCs than ESCs and did not contribute to the trophectoderm of the blastocysts after aggregation with 8-cell embryos. Therefore, differentiation ability into the trophoblast lineage might not be a unique characteristic of iPSCs derived from the in vivo milieu.

Results

Generation of reprogrammable mice with Oct4-GFP

The reprogrammable mouse is a useful tool to study the mechanisms underlying cellular reprogramming triggered by doxycycline administration19. We generated reprogrammable mice, which were the F1 generation of reprogrammable mice crossed with OG2 mice, which carry the Oct4-GFP (ΔPE) transgene. However, mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) from these heterozygous reprogrammable mice (OG2+/−/RTC4+/−) were rarely reprogrammed to Oct4-GFP+ cells after doxycycline treatment (data not shown). Reprogramming efficiency has been reported to be higher when the reprogrammable MEFs are homozygous for OKSM and Rosa26-M2rtTA transgenes (Ho/Ho) than when MEFs are heterozygous for each transgene (Het/Het)21. Thus, we generated a new set of reprogrammable mice homozygous for the transcriptional activator (M2rtTA; within the ubiquitously expressed Rosa26 locus) and doxycycline-inducible polycistronic cassette encoding the 4 reprogramming factors OSKM within the Col1a1 locus, and heterozygous for Oct4-GFP transgene (ΔPE)19. We named the reprogrammable mice rOG2 (for reprogrammable OG2) mice (Supplemental material Fig. S1).

First, we tested whether the rOG2 mice were successfully reprogrammable upon doxycycline induction. Neural stem cells (NSCs) and MEFs were obtained from rOG2 mice and cultured in doxycycline-containing ESC medium. At 10–15 days after culture with doxycycline, Oct4-GFP+ cells were observed. After further passage, the Oct4-GFP+ cells formed dome-like colonies, like ESCs, and were called rOG2-MEF-iPSCs (Supplemental material Fig. S3A and B). This result indicated that the reprogramming cassette and the Oct4-GFP transgene combination in rOG2 mice functioned properly in an in vitro system.

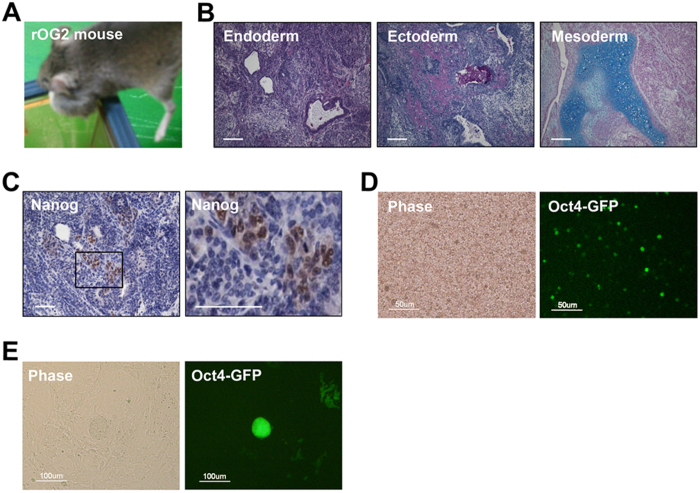

Spontaneous generation of teratomas in rOG2 mice

As previously reported, some reprogrammable mice spontaneously developed aggressively growing tumors that histologically presented as largely undifferentiated teratomas19,22. The rOG2 mice also formed teratomas spontaneously at the age of 4 weeks without doxycycline administration (Fig. 1A). Interestingly, these teratomas contained not only differentiated cell populations of all 3 germ layers (Fig. 1B) but also undifferentiated cell populations expressing Nanog (Fig. 1C), indicating that certain somatic cells in rOG2 mice were spontaneously reprogrammed into the pluripotent state in vivo. We dissociated the teratomas into single cells and examined them by fluorescence microscopy. Many Oct4-GFP+ cells were detected in the cells from teratomas (Fig. 1D and Supplemental material Fig. S2). The GFP+ cells could be pluripotent cells that were generated in vivo. The GFP+ cells were sorted by FACS and cultured on a feeder-layered dish in ESC culture medium. To our surprise, the GFP+ cells formed ESC-like colonies in ESC culture conditions (Fig. 1E). These ESC-like cells might be iPSCs induced by the in vivo environment (rOG2-T-rPSCs).

Figure 1. Generation of rOG2 mice and spontaneously forming teratomas.

(A) Spontaneously forming teratomas in rOG2 mice at the age of 4 weeks without doxycycline treatment. (B) Teratomas of rOG2 mice contained all 3 germ layer-like structures. Scale bar = 100 μm. (C) The undifferentiated cells in teratomas expressed Nanog, as shown by immunohistochemistry. Scale bar = 100 μm. (D,E) Oct4-GFP–positive cells in the teratomas were observed (Scale bar = 50 μm), which were sorted and cultured in conventional ESC culture condition without doxycycline. Scale bar = 100 μm.

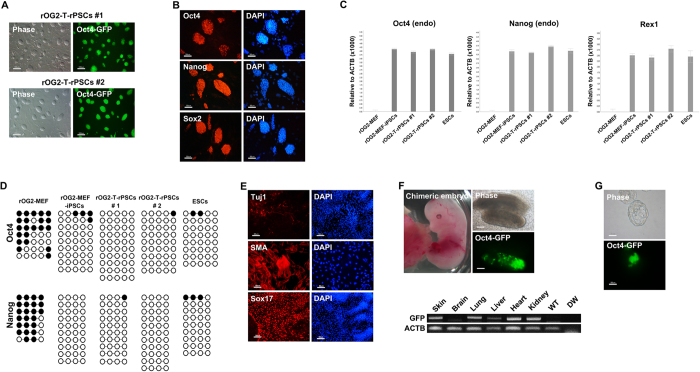

Characteristics of the in vivo iPSCs

By clonal expansion, we established 2 in vivo reprogrammed PSC (rPSC) lines, designated as rOG2-T-rPSCs #1 and #2, from the FACS-sorted GFP+ cells (Fig. 2A). Immunocytochemistry analysis showed that these rOG2-T-rPSCs were positively stained for core pluripotency markers, Oct4, Sox2, and Nanog (Fig. 2B). qRT-PCR analysis also showed that in vivo rPSCs expressed endogenous pluripotency markers Oct4 (endo), Nanog (endo), and Rex1 at levels similar to those of in vitro iPSC and ESCs (less than twofold; Fig. 2B,C). Next, we investigated the DNA methylation status in Oct4 and Nanog promoter regions of rOG2-T-rPSCs #1 and #2. Oct4 and Nanog promoter regions were completely demethylated in rOG2-T-rPSCs #1 and #2, as shown in rOG2-MEF-iPSCs and ESCs (Fig. 2D). The rOG2-T-rPSCs could differentiate into all 3 germ layers in vitro via embryoid body formation (Fig. 2E) and could form germline chimeras (Fig. 2F). Thus, PSCs reprogrammed in vivo from reprogrammable mice possess pluripotent characteristics, including the overexpression of pluripotency marker genes, DNA demethylation in Oct4 and Nanog promoter regions, and in vitro and in vivo differentiation potential. Next, to test the developmental potential to trophoblast lineage, we aggregated the in vivo iPSCs with 8-cell embryos and cultured them until the blastocyst stage. However, we could not observe the contribution of in vivo iPSCs to the trophectoderm of blastocysts (0/200) (Fig. 2G and Supplemental material Fig. S5).

Figure 2. Pluripotency of in vivo rPSCs.

(A) The established in vivo rPSCs expressed Oct4-GFP and were morphologically indistinguishable from mESCs. Scale bar = 100 μm. (B) Immunocytochemistry analysis (scale bar = 50 μm) and (C) qRT-PCR showed that in vivo rPSCs expressed pluripotency markers Oct4 (endo), Nanog (endo), Sox2, and Rex1, similar to in vitro iPSCs and ESCs. (D) DNA methylation status of Oct4 and Nanog promoter region in rOG2-T-rPSCs #1, #2. (E,F) The rOG2-T-rPSCs could differentiate into all 3 germ layers in vitro and in vivo Scale bar = 100 μm. (G) Aggregation potential of in vivo rPSCs into the inner cell mass of normal embryos. The in vivo rPSCs did not contribute to the trophectoderm lineage. Scale bar = 50 μm.

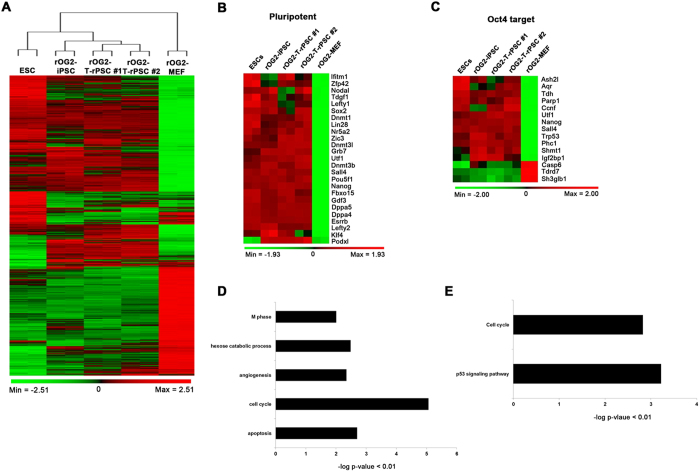

Gene expression pattern of in vivo iPSCs

To compare the molecular signatures of the rOG2-T-rPSCs, we performed gene expression profiling by microarray analysis (Illumina’s MouseRef-8 v2 Expression BeadChip). Pearson correlation analysis was used to cluster the cells according to the gene expression profiles. Heatmap and hierarchical clustering analyses showed that the global gene expression patterns of rOG2-T-iPSCs #1 and #2 cells were similar to those of ESCs and rOG2-MEF-iPSCs (Fig. 3A). However, in vivo rPSCs were more similar to in vitro iPSCs than ESCs. Scatter plot analysis showed that the r2 values (square of linear correlation coefficient) between ESCs and rOG2-T-riPSCs #1 and #2 cells were 0.96–0.97 (Supplemental material Fig. S4). The expression of pluripotency markers and Oct4 target genes in rOG2-T-rPSCs #1 and #2 was also closer to the rOG2-MEF-iPSCs than ESCs (Fig. 3B,C).

Figure 3. Gene expression pattern in vivo iPSCs.

(A) Heatmap data showed that the gene expression pattern of in vivo rPSCs was similar to that of control mESCs. (B,C) The heatmap of pluripotency and Oct4 target-related gene expression in ESCs, rOG2-MEF-iPSCs, rOG2-T-rPSCs #1 rOG2-T-rPSCs #2, and rOG2-MEF. (D) GO term and (E) KEGG pathway annotation using DAVID.

To further characterize the rOG2-T-iPSCs, we categorized the functions of the differentially expressed genes between rOG2-T-rPSCs and mESCs by Gene Ontology (GO) analysis. We isolated differentially expressed genes (more than a twofold change) and found that 415 probes were upregulated and 337 probes were downregulated in rOG2-T-rPSCs cells versus mESCs. We performed the GO term and KEGG pathway annotation using DAVID (http://david.abcc.ncif.gov/). According to GO analysis, upregulated genes in rOG2-T-rPSCs were enriched for the terms “apoptosis,” “cell cycle,” “angiogenesis,” “hexose catabolic process,” and “M phase” (p value < 0.01) (Fig. 3D, Supplemental material Table. 1), whereas downregulated genes in rOG2-T-rPSCs were enriched for “cell redox homeostasis” (p value < 0.001) (Supplemental material Table 2). In addition, pathway annotation of up- and downregulated genes was performed based on scoring and visualization of the pathways obtained from the KEGG database (http://www.genome.jp/kegg/). The upregulated genes in rOG2-T-rPSCs included “p53 signaling pathway” and “cell cycle” (p value < 0.01) (Fig. 3D,E, Supplemental material Table 3), whereas the downregulated genes included “propanoate metabolism,” “pyruvate metabolism,” “glycolysis/gluconeogenesis,” and “valine, leucine, and isoleucine degradation” (p value < 0.01) (Supplemental material Table 4).

Discussion

We established in vivo reprogrammed PSC lines from teratomas formed in reprogrammable mice containing the Oct4-GFP marker. These in vivo rPSCs expressed pluripotency markers, displayed an epigenetic status similar to that of ESCs, and could differentiate into all 3 germ layers in vitro and in vivo. Although gene expression profiles of in vivo rPSCs were similar to those of ESCs, they were closer to in vitro rPSCs than ESCs. This result is in conflict with reports of in vivo rPSCs being closer to ESCs than other iPSCs generated in vitro at the transcriptome level18. Abad et al. found that in vivo iPSCs were so potent that they differentiated into the trophoblast lineage18. However, we did not observe in vivo rPSCs contributing to the trophectoderm of blastocysts after aggregation with 8-cell embryos (Fig. 2G). A recent report showed that only ESCs expressing 2-cell–specific genes had the ability to contribute to both embryonic and extraembryonic tissues23. Moreover, ESCs grown in 2i-containing medium had a better potential to differentiate into trophoblast and extraembryonic endoderm than those grown in conventional ESC culture medium24. Therefore, the ability of iPSCs to differentiate into the trophoblast lineage might be related more to culture environment than to the in vivo milieu. Stable pluripotent stem cells do not reside in vivo; instead, they exist transiently during early embryonic development. Stable pluripotent stem cells were found to be established from pre-implantation embryo or post-implantation epiblast cells (5.5–6.5 dpc) were cultured in an in vitro system25. Therefore, the in vivo environment might not always favor pluripotential reprogramming, although pluripotency might be exhibited. Most importantly, trophoblastic differentiation is not a feature of pluripotency in mice. Thus, it is not reasonable to estimate the quality of pluripotent cells because of trophoblastic differentiation potential.

We used homozygous reprogrammable mice for in vivo rPSCs because MEFs from heterozygous reprogrammable mice were rarely reprogrammed to Oct4-GFP+ cells after doxycycline treatment in vitro. Only 1 copy of the reprogramming gene set might not be sufficient for the successful reprogramming of MEFs. Reprogramming efficiency is much lower in MEFs containing 1 copy of each transgene (Het/Het) than in MEFs that were homozygous for OKSM and Rosa26-M2rtTA transgenes21. It was recently reported that doxycycline-inducible reprogrammable MEFs by Oct4 and Tet1 could not be reprogrammed in traditional induction medium but were reprogrammed in specific optimal medium condition26. Therefore, the doxycycline-inducible reprogrammable system might need at least 2 copies of the gene set or suitable medium conditions for successful reprogramming.

Notably, the in vivo rPSCs in this study were derived from reprogrammable mice without doxycycline treatment. Some reprogrammable mice spontaneously formed aggressively growing tumors containing undifferentiated cells19. This phenotype might be attributed to the leaky expression of the transgene in an undefined cell type. The underlying mechanism is unclear; however, it is possible that the in vivo microenvironment influenced the regulation of doxycycline-inducible transgenes. Recently, we found a clue for the reactivation of integrated transgenes in an in vitro system. Integrated reprogramming factor genes, which were inactive in the iPSC state, were spontaneously re-activated when the iPSCs were differentiated into NSCs in vitro27. The reactivation of transgenes was closely correlated with the change in the levels of DNA methyltransferases during the differentiation of iPSCs. These results indicate that somatic cells could be reprogrammed into pluripotent cells not only in vitro but also in vivo19,22.

As shown by in vivo iPSC generation through teratoma formation, the process of iPSC derivation shares many characteristics with cancer development. During reprogramming, differentiated somatic cells acquire properties of self-renewal along with unlimited proliferation and exhibit global alterations of the transcriptional program, which are also critical events during carcinogenesis28. Partial reprogramming in vivo can bring about cancer development29,30. Ohnishi and colleagues showed that premature termination of reprogramming by transient expression of reprogramming factors led to tumor formation in vivo. These tumor cells could be fully reprogrammed into iPSCs by further induction of reprogramming factors. Therefore, tumor formation in vivo could be a result of incomplete reprogramming. In the present study, we showed that once completely reprogrammed, in vivo rPSCs formed through tumor formation possessed pluripotency and resembled in vitro iPSCs, which do not contribute to the trophectoderm.

Methods

The methods were carried out in accordance with the approved guidelines and all experimental protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Konkuk University

Generation of reprogrammable OG2 mice

Homozygous OG2 mice were crossed with homozygous reprogrammable (RTC4) mice, and then heterozygous OG2+/−/RTC4+/− mice were crossed with homozygous RTC4 mice. The resulting mice were OG2+/−/RTC4+/+, OG2+/−/RTC4+/−, OG2−/−/RTC4+/+, and OG2−/−/RTC4+/−. Finally, we selected OG2+/− RTC4+/+ mice (rOG2) by genotyping and test crosses with wild-type mice. The primers for genotyping were as follows: GFP sense 5′-GCAAGCTGACCCTGAAGTTCA-3′, GFP antisense 5′-TCACCTTGATGCCGTTCTTCT-3′, OKSM #1 5′-GCACAGCATTGCGGACATG-3′, OKSM #2-1 5′-CCCTCCATGTGTGACCAAGG-3′, OKSM #2-2 5′-CCCTCCATGTGTGACCAAGG-3′, M2rtTA #1 5′-GCGAAGAGTTTGTCCTCAACC-3′, M2rtTA #2 5′-AAAGTCGCTCTGAGTTGTTAT-3′, and M2rtTA #3 5′-GGAGCGGGAGAAATGGATATG-3′. Animals were maintained and used for experimentation under the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Konkuk University.

Isolation of in vivo rPSCs from rOG2 teratomas

Pieces of teratomas were washed and chopped in PBS containing 10 × penicillin/streptomycin/glutamine. Collected tissues were centrifuged at 900 rpm for 3 min. For single-cell dissociation, tissues were pipetted in 0.25% trypsin and incubated at 37 °C for 5 min. This step was repeated thrice. Dissociated tissues were then filtered through a 70 μm mesh cell strainer for single-cell purification.

Cell culture

GFP positive cells from teratomas were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 15% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1× penicillin/streptomycin/glutamine, 0.1 mM nonessential amino acids, 1 mM β-mercaptoethanol, and 103 units/ml leukemia inhibitory factors (LIF) on feeder layers.

RNA isolation and quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis

Total RNA was isolated using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and treated with DNase to remove genomic DNA contamination. Total RNA (1 μg) was reverse transcribed using the SuperScript III Reverse Transcriptase Kit (Invitrogen) and Oligo(dT) primer (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) reactions were set up in duplicate with the Power SYBR Green Master Mix (Takara) and analyzed with the Roche LightCycler 5480 (Roche). The primers for qRT-PCR used were as follows: Oct4 (endo) sense, 5′-GATGCTGTGAGCCAAGGCAAG-3′; Oct4 (endo) antisense, 5′-GGCTCCTGATCAACAGCATCAC-3′; Nanog (endo) sense, 5′-CTTTCACCTATTAAGGTGCTTGC-3′; Nanog (endo) antisense, 5′-TGGCATCGGTTCATCATGGTAC-3′; Rex1 sense, 5′-TCCATGGCATAGTTCCACAG-3′; Rex1 antisense, 5′-TAACTGATTTTCTGCCGTATGC-3′; ACTB sense, 5′-CGCCATGGATGACGATATCG-3′; and ACTB antisense, 5′-CGAAGCCGGCTTTGCACATG-3′.

Bisulfite genomic sequencing

To differentiate methylated from unmethylated CG dinucleotides, genomic DNA was treated with sodium bisulfite to convert all unmethylated cytosine residues into uracil residues using the EpiTect Bisulfite Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Briefly, purified genomic DNA (0.5–1 μg) was denatured at 99 °C and then incubated at 60 °C. Modified DNA, i.e., after desulfonation, neutralization, and desalting, was diluted with 20 μl of distilled water. Subsequently, bisulfite PCR (BS-PCR) was carried out using 1–2-μl aliquots of modified DNA for each PCR. The primers used for BS-PCR were as follows: Oct4 1st sense, 5′-TTTGTTTTTTTATTTATTTAGGGGG-3′; Oct4 1st antisense, 5′-ATCCCCAATACCTCTAAACCTAATC-3′; Oct4 2nd sense, 5′-GGGTTGGAGGTTAAGGTTAGAGGG-3′; Oct4 2nd antisense, 5′-CCCCCACCTAATAAAAATAAAAAAA-3′; Nanog 1st sense, 5′-TTTGTAGGTGGGATTAATTGTGAA-3′; Nanog 1st antisense, 5′-AAAAAATTTTAAACAACAACCAAAAA-3′; Nanog 2nd sense, 5′-TTTGTAGGTTGGGATTAATTGTGAA-3′; Nanog 2nd antisense, 5′-AAAAAAACAAAACACCAACCAAAT-3′.

Briefly, the amplified products were verified by electrophoresis on 1% agarose gel. The desired PCR products were used for subcloning using the TA cloning vector (pGEM-T Easy Vector; Promega). The reconstructed plasmids were purified, and individual clones were sequenced (Solgent Corporation).

Immunocytochemistry experiments

For immunocytochemistry, cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at room temperature. After cells were washed with PBS, they were treated with PBS containing 10% normal goat serum and 0.03% Triton X-100 for 45 min at room temperature. The primary antibodies used were anti-Oct4 (Oct4; monoclonal, 1:100, Abcam, sc-9081), anti-nanog (nanog; monoclonal, 1:200, Abcam, ab80892), anti-Sox2 (Sox2; polyclonal, 1:500, Millipore, AB5603), anti-tubulin, beta III (Tuj1; monoclonal, 1:1000, Millipore, MAB1637), anti-SMA (SMA; monoclonal, 1:200, Abcam, ab7817), and Sox17 (Sox17; polyclonal, 1:200, R&D systems, AF1924). For the detection of primary antibodies, fluorescence-labeled secondary antibodies (Alexa fluor 488 or 568; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) were used according to the specifications of the manufacturer.

Flow cytometry

Dissociated cells of teratomas were washed with PBS, and resuspended in ESC medium. GFP-positive cells were sorted directly into ESC medium using FACSAria cell sorter with FACSDiva software.

Chimera formation

In vivo iPSCs were aggregated with denuded post-compacted 8-cell–stage embryos to obtain an aggregate chimera. Eight-cell embryos flushed from 2.5-dpc B6D2F1 female mice were cultured in microdops of embryo culture medium under mineral oil. After cells were trypsinized for 10 s, clumps of iPSCs (4–10 cells) were selected and transferred into microdrops containing zona-free 8-cell embryos. Morula-stage embryos aggregated with iPSCs were cultured overnight at 37 °C and 5% CO2. The aggregated blastocysts were transferred into one of the uterine horns of 2.5-dpc pseudopregnant recipients. The primers for genotyping of GFP were as follows: GFP sense 5′-GCAAGCTGACCCTGAAGTTCA-3′, GFP antisense 5′-TCACCTTGATGCCGTTCTTCT-3′, ACTB sense 5′-CGCCATGGATGACGATATCG-3′, and ACTB antisense 5′-CGAAGCCGGCTTTGCACATG-3′.

Microarray-based analysis

Total RNA was isolated using an RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) and digested with DNase I (RNase-free DNase, Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Total RNA was amplified, biotinylated, and purified using the Ambion Illumina RNA amplification kit (Ambion) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Biotinylated cRNA samples (750 ng) were hybridized to each MouseRef-8 v2 Expression BeadChip (Illumina), and signals were detected using Amersham fluorolink streptavidin-Cy3 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) by following the Illumina bead array protocol. Arrays were scanned with an Illumina BeadArray Reader confocal scanning system according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Raw data were extracted using the software provided by the manufacturer (Illumina GenomeStudio v2011. 1, Gene Expression Module v1.9. 0). Array data were filtered on the basis of p-values of <0.05 in at least 50% of the samples. The selected probe signal value was logarithmically transformed and normalized using the quantile method. Comparative analyses were carried out using the local pooled error test and fold change. False discovery rate was controlled by adjusting the p-values using the Benjamini–Hochberg algorithm. Hierarchical clustering was performed using average linkage and Pearson distance as a measure of similarity.

Additional Information

How to cite this article: Choi, H. W. et al. In vivo reprogrammed pluripotent stem cells from teratomas share analogous properties with their in vitro counterparts. Sci. Rep. 5, 13559; doi: 10.1038/srep13559 (2015).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Biomedical Technology Development Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education, Science and Technology (grant no. 20110019489) and the Next-Generation BioGreen 21 Program (grant no. PJ01133802) funded by the Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea.

Footnotes

Author Contributions H.W.C., J.S.K. and J.T.D. wrote the main manuscript text and design the concept of the experiment. H.W.C., J.S.K. and Y.J.H. performed experiment and assembled data. H.G.S. and H.S. performed data analysis. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

References

- Nagata S. et al. Efficient reprogramming of human and mouse primary extra-embryonic cells to pluripotent stem cells. Genes to cells: devoted to molecular & cellular mechanisms 14, 1395–1404, 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2009.01356.x (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim M. J. et al. Conversion of genomic imprinting by reprogramming and redifferentiation. Journal of cell science 126, 2516–2524, 10.1242/jcs.122754 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chin M. H. et al. Induced pluripotent stem cells and embryonic stem cells are distinguished by gene expression signatures. Cell stem cell 5, 111–123 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Warren L. et al. Highly efficient reprogramming to pluripotency and directed differentiation of human cells with synthetic modified mRNA. Cell stem cell 7, 618–630, 10.1016/j.stem.2010.08.012 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaji K. et al. Virus-free induction of pluripotency and subsequent excision of reprogramming factors. Nature 458, 771–775, 10.1038/nature07864 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J. et al. Human induced pluripotent stem cells free of vector and transgene sequences. Science 324, 797–801, 10.1126/science.1172482 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D. et al. Generation of human induced pluripotent stem cells by direct delivery of reprogramming proteins. Cell stem cell 4, 472–476, 10.1016/j.stem.2009.05.005 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou H. et al. Generation of induced pluripotent stem cells using recombinant proteins. Cell stem cell 4, 381–384, 10.1016/j.stem.2009.04.005 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou P. et al. Pluripotent stem cells induced from mouse somatic cells by small-molecule compounds. Science 341, 651–654, 10.1126/science.1239278 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyanari Y. & Torres-Padilla M. E. Control of ground-state pluripotency by allelic regulation of Nanog. Nature 483, 470–473, 10.1038/nature10807 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ying Q.-L. et al. The ground state of embryonic stem cell self-renewal. Nature 453, 519–523 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirano K. et al. Human and mouse induced pluripotent stem cells are differentially reprogrammed in response to kinase inhibitors. Stem cells and development 21, 1287–1298 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maherali N. & Hochedlinger K. Guidelines and techniques for the generation of induced pluripotent stem cells. Cell stem cell 3, 595–605, 10.1016/j.stem.2008.11.008 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niu W. et al. In vivo reprogramming of astrocytes to neuroblasts in the adult brain. Nature cell biology 15, 1164–1175 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torper O. et al. Generation of induced neurons via direct conversion in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110, 7038–7043 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grande A. et al. Environmental impact on direct neuronal reprogramming in vivo in the adult brain. Nature communications 4, 2373, 10.1038/ncomms3373 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmazer A., De Lázaro I., Bussy C. & Kostarelos K. In Vivo Cell Reprogramming towards Pluripotency by Virus-Free Overexpression of Defined Factors. PloS one 8, e54754 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abad M. et al. Reprogramming in vivo produces teratomas and iPS cells with totipotency features. Nature 502, 340–345, 10.1038/nature12586 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadtfeld M., Maherali N., Borkent M. & Hochedlinger K. A reprogrammable mouse strain from gene-targeted embryonic stem cells. Nature methods 7, 53–55 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y. et al. BMP4-directed trophoblast differentiation of human embryonic stem cells is mediated through a ΔNp63+ cytotrophoblast stem cell state. Development 140, 3965–3976 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Polo J. M. et al. A molecular roadmap of reprogramming somatic cells into iPS cells. Cell 151, 1617–1632, 10.1016/j.cell.2012.11.039 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markoulaki S. et al. Transgenic mice with defined combinations of drug-inducible reprogramming factors. Nature biotechnology 27, 169–171 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macfarlan T. S. et al. Embryonic stem cell potency fluctuates with endogenous retrovirus activity. Nature 487, 57–63 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgani S. M. et al. Totipotent embryonic stem cells arise in ground-state culture conditions. Cell reports 3, 1945–1957 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boroviak T., Loos R., Bertone P., Smith A. & Nichols J. The ability of inner-cell-mass cells to self-renew as embryonic stem cells is acquired following epiblast specification. Nature cell biology 16, 516–528, 10.1038/ncb2965 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J. et al. The combination of tet1 with oct4 generates high-quality mouse-induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem cells 33, 686–698, 10.1002/stem.1879 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi H. W. et al. Neural stem cells differentiated from iPS cells spontaneously regain pluripotency. Stem cells 32, 2596–2604, 10.1002/stem.1757 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Porath I. et al. An embryonic stem cell–like gene expression signature in poorly differentiated aggressive human tumors. Nature genetics 40, 499–507 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobbs R. M. & Polo J. M. Reprogramming Can Be a Transforming Experience. Cell stem cell 14, 269–271 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohnishi K. et al. Premature termination of reprogramming in vivo leads to cancer development through altered epigenetic regulation. Cell 156, 663–677 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.