Abstract

Psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES) were first described in the medical literature in the 19th century as seizure-like attacks not related to an identified central nervous system lesion and are currently classified as a conversion disorder, according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5). While a universally accepted and unifying etiological model does not yet exist, several risk factors have been identified. Management of PNES should be based on interdisciplinary collaboration, targeting modifiable risk factors. The first treatment phase in PNES is patient engagement, which is challenging given the demonstrated low rates of treatment retention. Acute interventions constitute the next phase in treatment and most research studies focus on short-term evidence-based interventions. Randomized controlled pilot trials support cognitive-behavioral therapy. Other psychotherapeutic and psychopharmacological interventions have been less well-studied using controlled and uncontrolled trials. Within the discussion of acute interventions, we present a preliminary evaluation for feasibility of a mindfulness-based psychotherapy protocol in a very small sample of PNES patients. We demonstrated in 6 subjects that this intervention is feasible in real-life clinical scenarios and warrants further investigation in larger scale studies. The final treatment phase is long-term follow-up. Long-term outcome studies in PNES show that a significant proportion of patients remain symptomatic and experience continued impairments in quality of life and functionality. We believe that PNES should be understood as a disease that requires different types of intervention during the various phases of treatment.

Keywords: psychogenic nonepileptic seizures, treatment, therapeutics, mindfulness-based psychotherapy

Introduction

Psychogenic non-epileptic seizures (PNES) are sudden, involuntary seizure-like episodes or attacks that are neither related to electrographic discharges, like epileptic seizures, nor explained by other physiological paroxysms (e.g. cardiac arrhythmia, cataplexy). In the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), PNES are classified as a form of Conversion Disorder or Functional Neurological Symptom Disorder (FNSD).1

Many patients with FNSD, including PNES, may already be connected to mental health professionals for treatment of psychiatric comorbidities., but they usually seek help for their functional neurological symptom with other professionals, such as their primary care physician or neurologist. A sizable portion of patients seen in outpatient neurology clinics present with functional neurological symptoms.2 Regarding PNES in particular, 25–33% of admissions to Epilepsy Monitoring Units are diagnosed with PNES at discharge,3 and the prevalence during initial outpatient Neurology clinic visits has been estimated between 12 and 18%.4 Ultimately, both neurologists and mental health professionals are involved in the delivery of treatment, highlighting the need for interdisciplinary collaboration.

The main objective of this review is to describe a framework for treatment that highlights interdisciplinary collaboration, long-term needs at different stages and the current state of evidence-based interventions. We therefore emphasize the importance of collaborative care in the treatment of PNES, outline different treatment phases during the management of the disorder, review the current evidence-based treatments and summarize common challenges encountered in the care of this population. Within the context of a review of acute treatment options, where cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) has the strongest evidence so far, we present preliminary data from a case series for a mindfulness-based intervention. The objectives of the case series are to demonstrate feasibility of this psychotherapeutic intervention in real-life clinical scenarios and to evaluate its potential effectiveness in a very small sample to determine if larger scale studies should be considered.

The Historical Roots of the Problem in PNES Treatment

The first description in the medical literature of functional neurological symptoms dates to Jean-Martin Charcot (1825–1893), a re-known neurologist from the 19th century who practiced at the Hospital de la Salpêtrière in Paris. Charcot devoted a significant portion of his last years of practice to the study of “hysteria”, a condition that he contended could present with similar, but not identical, impairment as that seen in structural central nervous system lesions. In his original descriptions, Charcot cited all sorts of neurological symptoms that could present as a form of hysteria, using the term “hystero-epilepsy” to describe the paroxysmal episodes that were similar, but not identical, to epileptic seizures. Charcot originally described a different evolution of hysterical symptoms compared to epilepsy including a response to hypnotic suggestion and an association to certain personality profiles in patients with hysteria. He still embraced the idea that there was a lesion in the central nervous system, although not structurally identifiable, that was responsible for these symptoms.5

It was Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) who moved beyond his contemporaries and specified a mechanism where psychological distress, which could be unconscious to the patient, was the root of the hysterical symptoms. During the initial years of his career, Freud focused on this population and emphasized the role of trauma, both caused by external events or by inner experiences, and suggested that hysterical patients suffered from “incompletely abreacted psychical traumas” that were “converted” into the symptom. This allowed interventions such as hypnosis and eventually psychoanalysis to be proposed as treatment modalities to target the postulated etiology.6 These treatments facilitate expression and processing of the distress generated from earlier trauma, bringing the connection between trauma and symptom into consciousness. In psychoanalytic theory, this awareness is postulated to bring resolution to the hysterical symptom.

While modern Psychiatry has advanced significantly in the understanding of several disorders, our understanding of functional neurological symptoms at a neurophysiological level is in its early stages of characterization.7 While psychopathological models have also been delineated, no single etiology has been singled out as a “leading explanation” for functional neurological symptoms in general or PNES in particular, although several psychopathological dimensions appear to be particularly important including endogenous anxiety, avoidance behavior, dissociation, non-dissociative post-traumatic stress, abuse, interpersonal dynamics, personality structure and society and family factors.8 Many of these characteristics constitute traits that render a person more vulnerable to develop PNES, and we refer to them as “vulnerability traits”. A hypothetical model integrating the identified vulnerability traits in PNES proposes the oscillating and simultaneous existence of hyperarousal responses (signaled by hypervigilance, somatic preoccupation, emotional reactivity and emotional under-regulation) and hypoarousal responses (signaled by dissociation, avoidance tendencies, alexithymia (an inability to identify and/or describe emotional states), limited acceptance of emotions, and emotion over-regulation). Emotion regulation refers to the ability to control one’s behaviors when experiencing intense emotions, with under-regulation referring to states of intense emotions where the emotions direct behavior in an impulsive manner, and over-regulation referring to a distancing and disconnection from emotional states in an attempt to manage them.9 This model emphasizes the limited repertoire of adaptive behavioral responses seen in PNES patients due to the above-mentioned vulnerabilities, which possibly underlie an increased likelihood for involuntary complex symptomatic clusters to become activated.10

Our limited etiological understanding of the disorder impacts the development of treatment models for PNES. Obstacles that also contribute to the difficulty in conducting clinical trials in PNES include those that are intrinsic to PNES psychopathology, such as the tendency of patients to present in crises but reject support when offered, and others that are logistical in nature, such as driving restrictions.8

Historically, neurological symptoms of psychogenic origin became “orphan disorders” with no clear ownership by any discipline. While models of the disease, both at the psychopathological and neurobiological levels, are emerging, our understanding remains quite rudimentary and calls for more research in this area. Our increased understanding of brain function will unlock some of the mysteries behind functional neurological symptoms, particularly PNES, and will likely help guide the development of new and more effective treatments.

Disciplines involved in the treatment of PNES

Because of the nature of the symptoms that lead to the initial consultation, neurologists or general practitioners tend to be the first-line health professionals involved in the evaluation of PNES. The role of the neurologist is vital in establishing an accurate diagnosis. Early correct diagnosis can help patients promptly receive the treatment they need and prevent common iatrogenic complications that may occur if the condition continues to be misdiagnosed and mistreated. Iatrogenic complications typically involve inappropriate treatment with antiepileptic drugs (AEDs), with an estimated 75% of PNES patients receiving AEDs prior to correct diagnosis.11 Inappropriate diagnosis and treatment can even lead to death during interventions for prolonged episodes.12 It has also been established that the longer the delay to correct diagnosis, the poorer the outcome,13 although this notion has recently been challenged.14

In the absence of strong and wide-spread evidence-based treatments, the vast majority of professionals diagnosing patients with PNES, refer them to mental health professionals for treatment.15 While such referral is an appropriate intervention, no standardized method on how to provide such transition of care has been studied. This limited understanding of the most effective way to transition care may partially explain the low rates of engagement in treatment observed in PNES. At the same time, continued involvement of the neurologist who established the diagnosis is desirable to allow a safe taper of AEDs, prevent inappropriate treatment, evaluate the development of any new neurological symptoms, including change in semiology, and treat any co-morbid neurological condition.16

Collaboration with mental health professionals should ideally start at the time the diagnosis is being investigated. Mental health services are best utilized at three stages during the assessment and management of PNES: 1) while the diagnosis is being investigated to identify vulnerability traits, psychosocial factors, and psychiatric co-morbidities that can explain underlying psychopathological mechanisms; 2) during the delivery of the diagnosis, which also aims to engage patients in treatment; and 3) for the delivery of treatment that includes psychotherapeutic interventions specifically designed to target vulnerability traits, treatment of co-morbid psychiatric conditions, and monitoring of symptomatic and functional progress.

Treatment Phases in PNES

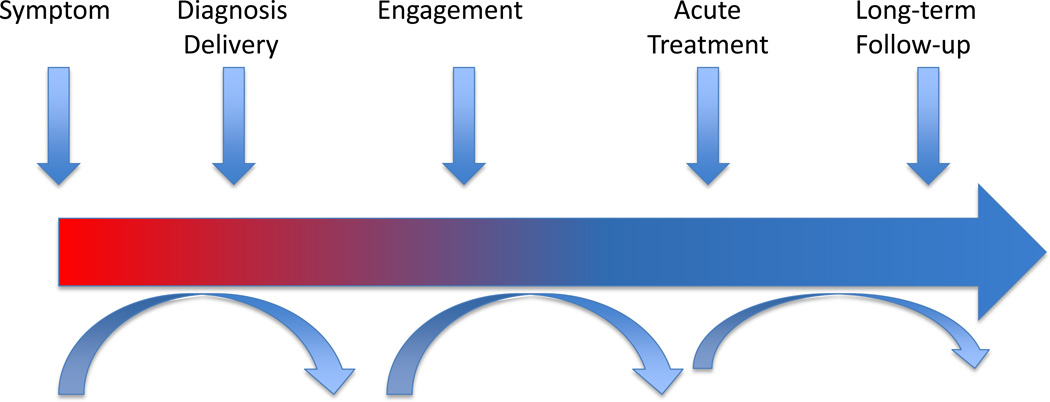

Once PNES patients enter mental health treatment, no guidelines exist on the type or duration of treatment that will help them achieve symptom improvement and functional recovery. PNES comprise a heterogeneous population17 and ideally different treatment protocols should exist for different PNES subgroups. In the absence of such guidelines, treatment of PNES could be conceptualized in phases (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Treatment Phases in PNES. After diagnosis delivery, management of PNES is conceptualized in three phases: engagement, acute treatment, and long-term follow-up. While many patients may move smoothly through these different stages, other patients may be retained at some of these phases.

The initial phase of treatment is engagement. This is particularly relevant in the PNES population given the tendency of patients to return to the Neurology consult after the diagnosis is well established to re-question its accuracy. Ideally, by the end of this phase, patients understand their diagnosis, do not seek further diagnostic evaluations elsewhere, establish contact with a mental health provider and start to actively participate in treatment.

The second phase of treatment involves an acute intervention. These include psychotherapeutic and psychopharmacological treatments that have as a primary goal the reduction of event frequency, but also improvement in secondary measures such as severity of psychiatric comorbidities, quality of life, functional recovery and medical resource utilization. Treatment research in PNES has primarily focused on these short-term interventions.

The final phase of treatment is comprised of long-term interventions. This is particularly relevant for the subgroup of PNES patients who remain symptomatic after the acute intervention phase and who will need ongoing care to optimize the use of resources and functional recovery.

Engagement

It has been suggested that delivery of the diagnosis may decrease event frequency and medical utilization.18 In one study, a standardized protocol for diagnosis delivery was used in 50 newly-diagnosed PNES subjects and rendered event freedom or drastic reduction in 14% of the subjects at 2 weeks and 20% at 11 weeks after the diagnosis was presented.19 Thus, the role of suggestibility as both a risk factor and a therapeutic tool should be considered and warrants future examination. Another possible explanation for improvement in this subset of patients is that individuals may gain an increased appreciation and awareness of the relationship between psychosocial stressors and their PNES events, which may facilitate symptomatic recovery through self-initiated acceptance and engagement in other more adaptive strategies to manage stressful situations. Most importantly, delivery of the diagnosis may help with engagement in treatment, as most patients will remain symptomatic after they learn about their condition, and even those who become symptom-free may benefit from modifying some of their risk factors to prevent recurrence. Delivery of the diagnosis should be done carefully and specific protocols exist that outline elements to be considered during the task, including a multidisciplinary setting, objective discussion of the findings, a statement emphasizing that providers believe the symptoms are real, explanation of the psychogenic nature of the disorder, and reason for mental health treatment.20 Use of educational materials may enhance the information provided during the delivery of the diagnosis.

In a study that followed patients with an established PNES diagnosis who attended an outpatient neuropsychiatric evaluation, and then were offered psychotherapy and psychiatric follow-up in the same setting, approximately 50% of patients remained engaged after 5 psychotherapy sessions. The only predictor for engagement was relationship status (being married or having a live-in partner).21 This finding demonstrates the difficulty of PNES patients to remain connected to mental health services, even when they accept an initial referral for integrated neuropsychiatric services.

There is currently no standardized method to establish or predict PNES patients’ engagement in treatment. There are a multitude of factors that may influence patients’ active participation in treatment. The section “Challenges in the management of PNES” below enumerates factors that are both patient- and provider-dependent. Many patients seek further diagnostic evaluations even after definitive diagnosis. Integrated health care systems may allow tracking of these encounters, so that unnecessary medical diagnostic procedures and interventions are not repeated. Most importantly, these recurrent contacts with the health care system should turn into opportunities to reinforce engagement in the recommended treatment.

Currently, there are no systematically studied therapeutic strategies specific to PNES that the neurologist or mental health professional could readily use to reinforce participation in treatment. Motivational interviewing has been studied in a wide array of long-term modifiable health problems and has established evidence of reducing ambivalence about treatment and enhancing patients’ behavioral change in favor of their health.22 Training neurologists in these brief interventions could hypothetically modify patients’ ambivalence about treatment.

In summary, engagement is a pivotal initial phase of treatment in PNES. While some patients may be ready to become active participants in mental health treatment immediately after the diagnosis is established, other PNES patients will take longer to accept such referrals or to meaningfully engage in treatment. Awareness of this phase of treatment and use of simple clinician skills to enhance behavioral change, such as the ones provided in motivational interviewing, may have the potential to help patients move through their treatment course.

Acute Treatment

Acute treatment comprises short-term interventions, both psychotherapeutic and psychopharmacological, that require a patient’s ongoing participation. Most of the research done in PNES treatment focuses on these active treatments. In this section we will briefly review the currently available evidence.

Psychotherapy trials

Goldstein and colleagues23 compared cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) against “standard medical care” (SMC) in a randomized controlled trial (RCT) of 66 subjects. The content of this CBT approach emphasized the following components through 12 outpatient sessions: 1) treatment engagement, 2) reinforcement of independence, 3) distraction, relaxation, and refocusing techniques at the earliest signs of an event, 4) graded exposure to avoided situations, 5) cognitive restructuring, and 6) relapse prevention. SMC consisted of up to seven neuropsychiatric appointments that focused on psycho-education, support measures, and anti-epileptic drug withdrawal. Both groups received SMC. There was no significant difference in event frequency at baseline between the two groups (SMC median = 8 events/month; CBT + SMC median = 12 events/month). At the end of the 12-session treatment, the CBT group exhibited significantly lower event frequency (SMC median = 6.75 events/month; CBT + SMC median = 2 events/month) (p <.002), with a large between-group effect size (0.75). However, at 6-month follow-up, the between-group effect size (SMC median = 5 events/month; CBT + SMC median = 1.5 events/month) was modest (0.42) and not statistically significant (p < .08). Therapist contact was greater in the active group, and this level of contact was not controlled for in the SMC group, which may explain the decrease in between-group difference over time following the active phase of treatment.

LaFrance and colleagues24 conducted a pilot clinical trial at 3 academic medical centers, where subjects were randomized to receive cognitive behavioral therapy informed psychotherapy (CBT-ip), medication (flexible-dose sertraline), CBT-ip with medication or treatment as usual. CBT-ip was based on modifications from an epilepsy therapy workbook to target behaviors and cognitions seen in PNES, and consisted of 12 weekly, 1-hour individual sessions. The same intervention had shown efficacy in a within-subject study previously.25 Treatment-as-usual consisted of regular neurological follow-up plus biweekly study assessments (similar to those in the other study arms). Thirty four subjects were included in the final analysis, which showed a within-group significant reduction in monthly PNES events of 51% (p=.01) in the CBT-ip arm and 59% (p=.008) in the combination arm, and non-significant reductions of 27% in the sertraline arm (p=.08) and 39% in the treatment-as-usual arm (p=.19). The study was not powered to detect between-group differences. The CBT-ip group showed significant reductions in secondary measures including depression, anxiety, quality of life and level of functioning. The combination group showed reductions in some secondary measures, including level of functioning. The other arms did not show improvement in secondary measures.

CBT has also been examined with an uncontrolled prolonged inpatient program.26 The duration of the program ranged from 2 to 6 months, with an average of 4.8 months. Reductions were significant by the end of the program and were maintained 6 months post-discharge. An uncontrolled group-CBT trial done in a small mixed group of patients with PNES and other functional neurological symptoms demonstrated improvement in emotional well being, although data from event frequency was not recorded.27

Other interventions examined in RCTs include group psychoeducation, inpatient paradoxical intention and hypnosis. An RCT evaluated group psychoeducation versus routine seizure clinic follow-up for 3 months and found the group intervention superior for social and work adjustment at the end of treatment. This improvement was maintained 3 months after the treatment ended. However, the group intervention did not differ from standard medical care in terms of event frequency.28 Another RCT compared a 3-week inpatient intervention based on paradoxical intention (patients were encouraged to have an event) versus outpatient administration of diazepam for 6 weeks. Results showed improvement based on percentage of event freedom and improvement in anxiety severity at the end of treatment in both intervention groups.29 Two RCTs investigated the efficacy of hypnosis for FNSD, in a sample that included but was not limited to PNES, preventing the analysis of event frequency as a primary outcome. The first study compared two 12-week inpatient multi-disciplinary treatments that only differed in the administration of 8 sessions of hypnosis in the intervention group. Both groups showed improvement in psychopathology, severity of motor conversion symptoms and perceived impairment at the end of treatment and at the 3-month follow-up, but there was no difference between the groups.30 The second RCT compared outpatient administration of hypnosis over 10 weeks versus a waitlist control. The intervention group showed significant improvement in motor conversion symptom severity and perceived motor impairment, but not in psychopathology.31

A variety of other approaches have been examined in uncontrolled studies. Brief augmented psychodynamic psychotherapy,32 group psychodynamic psychotherapy,33 and other group educational interventions34–36 have been reported to have positive effects on event frequency. Health care utilization was significantly reduced in patients who underwent brief psychodynamic psychotherapy (from 5–10 health care contacts in the 3 months before treatment to 1–4 health care contacts in the 3 months after treatment),32 as were depression and overall psychopathology severity in those who received group psychodynamic psychotherapy.33

Psychopharmacology trials

Few studies have evaluated the utility of psychotropic medications in the treatment of PNES. La France and colleagues37 conducted a randomized, placebo-controlled trial evaluating the efficacy of flexible-dose sertraline over 12 weeks aimed at reducing event frequency and improving psychiatric co-morbidities and psychosocial domains. The final analysis included 33 subjects with one or more events in the 2 weeks prior to enrollment. There was no difference between groups in biweekly event frequency change over the course of treatment (risk ratio = 0.51, p < .29). When groups were analyzed separately, however, the sertraline arm showed a 45% decline in biweekly event frequency (ratio = 0.55, p < .03), while the control group showed an 8% increase (ratio = 1.08, p < .78). There were no between-arm differences in secondary psychiatric and psychosocial outcome measures. The limited sample size made this well-conducted study underpowered to establish treatment efficacy. An open-label, uncontrolled study of flexible-dose venlafaxine38 resulted in significant event reduction, as well as a significant decrease in anxiety and depression severity. Outcome measures were obtained over a period of 5 months. This study required patients meeting criteria for a depressive or anxiety disorder at baseline.

Overall, the evidence-based literature on PNES treatment remains limited to date. One pilot randomized controlled trial (RCT) of a psychopharmacological intervention (sertraline),37 one pilot RCT of CBT23 and a multicenter randomized trial that included CBT-ip, sertraline, combination treatment and treatment-as-usual24 are the most rigorously designed. These studies had limited power, and while we cannot claim strong support for these interventions at this point, these are very promising approaches that warrant further study. Other treatment reviews, including a Cochrane Review of psychological treatments for PNES, provide more detail about many of the specific studies cited above.20,39

CBT is considered the “second wave” of behavioral therapies and has wide-range acceptance and evidence as an effective treatment for many psychiatric disorders. “Third wave” behavioral approaches incorporate mindfulness as a core psychotherapeutic element in manualized programs and is gaining evidence as an effective form of treatment for several psychiatric disorders, including but not limited to mood and anxiety disorders40 and substance use disorders.41 A case series using a mindfulness-based psychotherapeutic program is presented below, providing preliminary evidence of the feasibility and possible effectiveness of this treatment modality for PNES.

A Mindfulness-Based Intervention for PNES: Case Series.

Mindfulness-based interventions are rooted in the widely accepted concept of mindfulness defined as, “paying attention in a particular way: on purpose, in the present moment and non-judgmentally.”42 Mindfulness is a primary intervention component in specific psychotherapeutic approaches, such as acceptance and commitment therapy (ACT),43 dialectical behavioral therapy (DBT),44 mindfulness-based stress reduction (MBSR),42 and mindfulness-based cognitive therapy (MBCT).45 Sufficient empirical evidence already exists for the use of these interventions to treat a range of psychiatric disorders, such as mood and anxiety disorders and substance use disorders, and problems in living, and outcome-based research continues to grow rapidly.39,40

Mindfulness-based psychotherapies have not been systematically evaluated for the treatment of PNES or other functional neurological disorders, but they may be well suited for this population from a theoretical perspective as they target underlying psychopathological vulnerabilities, such as poor recognition or non-acceptance of emotional states.9,46

The objective of this case series is to report the feasibility and efficacy of a 12-session mindfulness-based psychotherapy protocol, with outcome measures recorded at 6 and 12 sessions.

Methods

Subjects

Six adult female patients with PNES were consecutively evaluated and treated with a 12-session psychotherapy protocol at the University of Illinois Medical Center at Chicago between 2009 and 2011. All subjects provided informed consent for this research protocol in accord with the local internal review board. PNES diagnosis was established through video-electroencephalography (v-EEG) monitoring capturing a typical event (documented PNES),47 except in one case (subject # 5) where the typical attack was not captured on v-EEG, but a 72-hour EEG did capture the spell with no EEG correlate and semiology was highly suggestive of a psychogenic etiology based on home video (clinically established PNES), including the epileptologist’s review of the video.47 One patient had comorbid epilepsy, but her PNES and epileptic seizures were clearly different in semiology with the frontal lobe seizures having a motor manifestation and the PNES events presenting with brief lapses of unresponsiveness.

Intervention

All six patients participated in a four-module mindfulness-based individual psychotherapeutic program to be completed in 12 sessions. Timing for completion of each of the 4 core modules was flexible. Frequency of sessions was flexible depending on patient availability. A weekly to biweekly frequency of sessions was encouraged but not always possible.

Individual modules focused on the development of each of the following skills: module 1) psychoeducation and goal setting (with emphasis on goals outside of symptom control); module 2) stress management training (including training in relaxation techniques to reduce vulnerability towards events); module 3) mindfulness training (core mindfulness training, including discussion of a ‘willing’ and accepting approach and attitude to life); module 4) emotion recognition, acceptance and behavioral regulation (which basically includes application of mindfulness skills into any emotional or physiologically uncomfortable experience). A fifth module “treatment review and relapse prevention module” was not considered part of the 4 core modules and in most cases was completed beyond the 12th session.

Measures

Weekly PNES count was the primary outcome measure and was recorded at every session (by patient-completed event log and confirmed and reviewed by the therapist). Psychopathology self-rating scales were secondary outcome measures and were completed at the 6th and 12th sessions and included the Beck Depression Rating Scale-II (BDI-II), and the Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale-21 (DASS-21). Unfortunately, these secondary measures were not collected at all time points for all subjects. Concurrent psychopharmacological interventions were kept minimal but allowed as dictated by standard psychiatric care.

Results

Baseline demographic and clinical information is shown in Table 1. Weekly PNES counts at baseline, sixth session, and 12th session are listed in Table 2. The fact that all recruited patients were female was not intentional and is rather representative of female preponderance in the PNES population.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Data.

| ID | Age* | Ethnicity | Marital Status |

Employment | Education | Age Onset |

Delay in Dx (mo) |

Semiology | Psychiatric Diagnoses |

Neurological Diagnoses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 25 | White | Single | Unemployed | 7th grade | 25 | 2.5 | Motor and altered awareness | MDD, PaD, past hypomania | Headaches |

| 2 | 49 | White | Partnered | Employed | Post-graduate | 48 | 6 | Motor and somatosensory | GAD, past MDD in remission, ETOH abuse, cluster C PD (OCPD) | None |

| 3 | 59 | Asian PI | Widow | Disabled | Some college | 36 | 48 | Motor and somatosensory | Dysthymic disorder, GAD | None |

| 4 | 45 | White | Married | Employed | Some college | 40 | 0 | Motor | Denied | None |

| 5 | 18 | White | Single | Student | High School | 17 | 1 | Altered awareness | PaD, GAD | Frontal lobe epilepsy |

| 6 | 42 | White | Married | Employed | High School | 32 | 12 | Motor and altered awareness | Dyslexia, MDD recurrent, PaD, ETOH dependence in remission | Headaches, OSA |

At baseline

Abbreviations: dep: dependence; Dx: diagnosis; ETOH: Alcohol; GAD: Generalized Anxiety Disorder; MDD: Major Depressive Disorder; min: minutes; mo: month; Neuro: neurological; OCPD: Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder; OSA: Obstructive Sleep Apnea; PaD: Panic Disorder; PD: Personality Disorder; PI: Pacific Islander; Psych: psychiatric; r/o: rule out; Sx’s: symptoms.

Table 2.

Weekly PNES count, changes in other measures and psychopharmacological changes during treatment.

| ID # | Weekly PNES count at baselinea |

Weekly PNES count at 6th sessionb |

Weekly PNES count at 12th sessionb |

Weeks to complete 12 session |

BDI-II Baseline |

BDI-II Final |

DASS-A Baseline |

DASS-A Final |

Psychopharmacological changes during psychotherapy course |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 0 | 43 | 38 | N/A | 16 | N/A | Citalopram up to 30 mg/day; Clonazepam 0.5 mg as needed. |

| 2 | 8.5 | 7 | 5 | 15 | 26 | 4 | 3 | 5 | Paroxetine and Sertraline tried; both stopped within 2 wks due to side effects. |

| 3 | 2.125 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 17 | 6d | 2 | 2d | No changes. |

| 4 | 0.25 | 0 | 0 | 37 | 0 | 8 | 1 | 3 | Citalopram tried for less than a week and stopped due to side effects. |

| 5 | 70 | 5 | 2c | 20 | 11 | 0 | 7 | 2 | No psychopharmacological treatment. |

| 6 | 24.5 | 0 | 11 | 21 | 3 | 1d | 7 | 1d | Buspirone, Duloxetine, Mirtazapine; escitalopram/amitriptyline discontinued. |

Abbreviations: BDI-II (Beck Depression Inventory-II); DASS-A (Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale – Anxiety Subscale); DFI (Disruption in Functioning Index); N/A (non-applicable – information not obtained)

Weekly average from previous 2 months;

Weekly average since previous session;

Last session is 10th session;

ratings collected at session 6 (not collected at session 12).

Most patients experienced a notable decline in their weekly PNES count from baseline (median of 5.5 weekly events, mean of 18 weekly events) by the sixth session (median of 0.75 weekly events, mean of 2.25 weekly events), and maintained by the twelfth session (median of 0 weekly event, mean of 2.67 weekly events). The mean difference between pre- (baseline) and post-treatment (12th session) was of −14.98 weekly PNES events. The limited number of participants prevents more quantitative statistical analyses. The pre- and post- mean difference in event frequency is similar to the one previously reported in a CBT pilot trial, where the difference was −10.1.25

As shown in table 2, all subjects experienced a reduction in event frequency, and three of them had complete remission of episodes (based on weekly PNES frequency at the time of the 12th session). The patient who had comorbid epilepsy had no changes in her anti-epileptic regimen and no change in her epileptic seizure frequency during the course of treatment. With this very limited sample, analysis of prognostic factors could not be conducted. It is noteworthy, however, that the two patients that experienced the least improvement (subjects # 2 and # 6), had a history of alcoholism and recurrent unipolar major depression (not present in other subjects), and had more psychiatric diagnoses than the other subjects. A discussion of established prognostic factors is included in the “Long-Term Treatment” section below.

Secondary outcome measures were not collected at all three time points for all patients, and should only be considered exploratory outcome measures in this study. For information purposes, the initial and final collection of secondary measures is shown in table 2, many of which showed improvement. Because this was a protocol given while other treatments were allowed, psychopharmacological changes did take place, as noted in Table 2, to address co-morbid psychiatric conditions. The psychopharmacological management did not intend to address PNES frequency, but focused on secondary symptoms, such as depression, anxiety, and insomnia.

The intervention took place in a flexible clinical setting that allowed for individualized timing of the intervention and for concurrent psychopharmacological changes, which are the most salient limitations of this case series. Duration of each module was customized for each patient, but always occurred within the 12-session frame and covered the 4-module content. Due to this flexibility, it remains unknown if the improvement seen at week 6 in most subjects was specifically related to mindfulness training or to the overall exposure to treatment. Further research testing this mindfulness-based therapy in a randomized controlled trial, with adequate power to establish efficacy, while also restricting variability (such as psychopharmacological changes and customization of module duration), will help clarify whether this intervention may be added to the repertoire of promising treatments for this condition. This case series shows that mindfulness-based psychotherapy can be conducted in this population and requires further investigation regarding treatment efficacy. However, at this point, there is not enough data to recommend this mindfulness-based intervention as a treatment for PNES.

Many of the principles utilized in mindfulness-based psychotherapies complement rather contradict those offered by CBT. For instance, in the protocol presented by Goldstein et al23 the initial sessions focused on engagement, reinforcement of independence and stress management training, which are similar to the first two modules of our protocol. However, the incorporation of mindfulness training in module 3 and its application to emotion processes in module 4 is different than CBT, where the rest of the treatment focuses on the exposure to avoided situations and identification of maladaptive cognitions that perpetuate symptoms. Our reliance on mindfulness training is based on PNES subjects’ difficulty in recognizing, accepting and/or managing their emotions.9 We therefore believe that re-training in these skills may address an important aspect of the underlying psychopathology seen in PNES.9.10 While this may be an advantage of mindfulness-based treatment, on the other hand, the level of meta-cognition required for such training may impact patients’ assimilation of the treatment. This will require careful monitoring in future studies. Ultimately, if mindfulness-based psychotherapy is confirmed as effective in larger scale studies, subsequent studies should determine what kinds of patients would most benefit from each intervention (CBT, mindfulness-based intervention, psychopharmacological treatment) so that treatments can be individualized.

Comorbid epilepsy and psychiatric background are among the most important variables to consider when evaluating the effectiveness of treatments for PNES. Unfortunately, we are at the very early stages of evaluating these treatments and sample sizes have been too small or inclusion criteria too restrictive to make any conclusions in terms of treatment efficacy based on such variables.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Data.

| ID | Age* | Ethnicity | Marital Status |

Employment | Education | Age Onset |

Delay in Dx (mo) |

Semiology | Psychiatric Diagnoses |

Neurological Diagnoses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 25 | White | Single | Unemployed | 7th grade | 25 | 2.5 | Motor and altered awareness | MDD, PaD, past hypomania | Headaches |

| 2 | 49 | White | Partnered | Employed | Post-graduate | 48 | 6 | Motor and somatosensory | GAD, past MDD in remission, ETOH abuse, cluster C PD (OCPD) | None |

| 3 | 59 | Asian PI | Widow | Disabled | Some college | 36 | 48 | Motor and somatosensory | Dysthymic disorder, GAD | None |

| 4 | 45 | White | Married | Employed | Some college | 40 | 0 | Motor | Denied | None |

| 5 | 18 | White | Single | Student | High School | 17 | 1 | Altered awareness | PaD, GAD | Frontal lobe epilepsy |

| 6 | 42 | White | Married | Employed | High School | 32 | 12 | Motor and altered awareness | Dyslexia, MDD recurrent, PaD, ETOH dependence in remission | Headaches, OSA |

At baseline

Abbreviations: dep: dependence; Dx: diagnosis; ETOH: Alcohol; GAD: Generalized Anxiety Disorder; MDD: Major Depressive Disorder; min: minutes; mo: month; Neuro: neurological; OCPD: Obsessive-Compulsive Personality Disorder; OSA: Obstructive Sleep Apnea; PaD: Panic Disorder; PD: Personality Disorder; PI: Pacific Islander; Psych: psychiatric; r/o: rule out; Sx’s: symptoms.

Table 2.

Weekly PNES count, changes in other measures and psychopharmacological changes during treatment.

| ID # | Weekly PNES count at baselinea |

Weekly PNES count at 6th sessionb |

Weekly PNES count at 12th sessionb |

Weeks to complete 12 session |

BDI-II Baseline |

BDI-II Final |

DASS-A Baseline |

DASS-A Final |

Psychopharmacological changes during psychotherapy course |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2.5 | 1.5 | 0 | 43 | 38 | N/A | 16 | N/A | Citalopram up to 30 mg/day; Clonazepam 0.5 mg as needed. |

| 2 | 8.5 | 7 | 5 | 15 | 26 | 4 | 3 | 5 | Paroxetine and Sertraline tried; both stopped within 2 wks due to side effects. |

| 3 | 2.125 | 0 | 0 | 22 | 17 | 6d | 2 | 2d | No changes. |

| 4 | 0.25 | 0 | 0 | 37 | 0 | 8 | 1 | 3 | Citalopram tried for less than a week and stopped due to side effects. |

| 5 | 70 | 5 | 2c | 20 | 11 | 0 | 7 | 2 | No psychopharmacological treatment. |

| 6 | 24.5 | 0 | 11 | 21 | 3 | 1d | 7 | 1d | Buspirone, Duloxetine, Mirtazapine; escitalopram/amitriptyline discontinued. |

Abbreviations: BDI-II (Beck Depression Inventory-II); DASS-A (Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale – Anxiety Subscale); DFI (Disruption in Functioning Index); N/A (non-applicable – information not obtained)

Weekly average from previous 2 months;

Weekly average since previous session;

Last session is 10th session;

ratings collected at session 6 (not collected at session 12).

Long-Term Treatment

Few studies have looked at outcomes following acute interventions for PNES. Kanner et al48 identified three subgroups of patients in a study that followed 45 subjects after a course of psychotherapy treatment. Poor prognostic indicators for patients who remained symptomatic during and after treatment included a history of recurrent depression, chronic trauma and borderline personality disorder. The other subgroups included those patients who improved during treatment and maintained their improvement after treatment ended, and another subgroup of patients who improved during treatment but could not maintain their improvement after treatment ended. This last subgroup was characterized from the other subgroups by their inability to recognize a stressor at the onset of illness. This study demonstrated that, despite a similar acute intervention, outcomes vary significantly in PNES depending on certain prognostic factors, mostly dictated by subjects’ psychiatric background.

Outcome studies after diagnosis delivery have been conducted at different time points, and it is difficult to generalize these results as it remains unclear how consistent these results remain over the years. A retrospective cohort study found that 38% of PNES patients were event-free 6–12 months after delivery of the diagnosis. Patients enrolled in this study had not completed any formal psychotherapeutic intervention. Positive predictors of event freedom included lack of a history of anxiety or depression, not receiving social security benefits, male gender, and a history of being bullied. In the patients still having spells, approximately one-third had a 50% increase in frequency over this same time period.49 Another study investigating outcomes over a similar timeframe found that 25% of PNES patients developed new medically unexplained symptoms 6–12 months after diagnosis, with those with continuing events and history of health-related psychological trauma being at higher risk.50

Long-term studies have identified a decrease in acute care utilization after the diagnosis was established.51,52 Particularly, during the 24 months post-diagnosis, a 39% reduction in overall Emergency Department (ED) visits and 51% reduction in ED visits for neurological causes were observed in one study.52

A longer-term study reviewed medical utilization in 188 patients 5–10 years after diagnosis and found that 26% of PNES-only patients (no comorbid epilepsy) still presented with “seizure complaints” to their primary care practitioner or to a hospital within the previous 6 months at the 5–10 year post-diagnosis time point. Anti-epileptic drug (AED) use was reduced from 49% to 11% in PNES-only patients within the same time frame. This study, like many that evaluated long-term outcomes in PNES, did not track attendance to recommended treatment, although 62% of the subjects had been recommended to receive psychotherapy when the diagnosis was originally delivered.53 Another study looking at long-term outcomes in PNES demonstrated that 4.1 years after diagnosis, 71% continued to be symptomatic.54

Well-established poor outcome predictors in PNES include comorbid epilepsy or various psychiatric diagnoses, personality disorder, history of trauma, violent seizure semiology, ED visits at baseline, interpersonal difficulties, and receiving social security benefits.49,53,54 Longer duration of illness prior to diagnosis has traditionally been considered a negative prognostic factor, but new evidence does not seem to support such a statement.14

While evidence shows that there is a subgroup of patients that will improve over time, even regardless of formal interventions, there still is a sizable proportion of patients that will continue to experience symptoms (seizure-like or other forms of conversion or somatization) and seek treatment for their events through ED visits and, more alarmingly, a smaller proportion who will continue to receive inappropriate care, for instance through AED prescription. Some factors at baseline may provide clinicians with an index of suspicion about long-term prognosis. Despite the availability of data regarding long-term outcomes in PNES, no treatment studies exist that focus on the long-term management of those patients with protracted symptoms.

We would like to propose a treatment model where, beyond the initial acute intervention phase, PNES patients with persistent symptoms continue to receive treatment to alter factors most likely to be associated with poor prognosis. This type of treatment may take different forms, and may include long-term psychotherapy, case management, and ongoing psychotropic management of psychiatric co-morbidities among other individualized interventions.

While event freedom continues to be the goal in PNES treatment, clinicians need to be aware that equally important goals are the appropriate and safe management of the events that continue to occur and the amelioration of factors that precipitate their recurrence. This overall treatment frame is similar to the approach to epilepsy patients.

Challenges in the management of PNES

Treatment of patients with PNES can be challenging at all stages of treatment due to a number of patient-dependent and provider-dependent factors.

Patient-dependent factors

Many PNES patients have difficulty accepting the role of psychological factors in their symptomatic presentation, making engagement in treatment difficult. Carton and colleagues55 determined that feeling “relieved” after the diagnosis was a positive prognostic factor, while feeling “confused” about it was a negative prognostic factor. Special attention should be placed to those patients reluctant to accept the diagnosis, as they may require more time and effort from the first-contact clinician (usually a neurologist) to help with eventual engagement in mental health treatment.

Avoidance tendencies56 are well documented in PNES and their presence steers patients away from feared stimuli (such as distressing emotions or traumatic memories). Avoidance has been proposed as one of the underlying pathological mechanisms in the disorder. In the clinical arena, this translates into patients avoiding any form of treatment that may expose them to such feared stimuli. The re-labeling of psychotherapy as a collaborative “skills-based training” to get patients “equipped” to face such stimuli may re-create patients’ conceptualization of psychotherapy and make it more acceptable, instead of the traditional conceptualization of psychotherapy as a setting where patients need to discuss and face their most avoided and feared experiences.

PNES patients generally hold an external locus of control regarding their health.57 Due to this trait, patients may hold a false expectation that they are passive recipients of treatment, rather than active participants in a new modality of managing internal and external experiences, where therapists serve as guides for behavioral changes. Especially for those patients naïve to psychotherapeutic interventions, this may be a drastic change in approach that needs to be explicit.

Development of further medically unexplained symptoms, aside from the PNES, are very common, even after proper diagnosis.50 Clinicians need to be attentive to these varied somatoform presentations, as most of these symptoms will hold a similar psychogenic origin. When appropriate, clinicians should discourage ongoing misuse of medical resources, reassure patients, and refocus patient’s attention on their recovery through mental health treatment.

The psychiatric complexity and heterogeneous presentation of PNES patients17 is puzzling to many mental health professionals. Mental health providers should seek consultation with a professional versed in these disorders to ensure diagnostic accuracy and proper treatment planning.

Finally, PNES patients tend to present in crises, preventing new skills from being regularly practiced and developed. The need for consistent engagement in regular sessions, and systematic practice of these new skills when not in a crisis should be emphasized as necessary for persistent changes to take place. Other logistic problems, such as driving or transportation limitations, may impact proper delivery of treatment as well.

Provider-dependent factors

Providers have also played a role in delaying proper attention to this clinical entity. There is limited familiarity with PNES among mental health professionals, even though often times they are the ones providing treatment, both immediately after diagnosis and on a long-term basis. Adequate treatment requires collaboration between Neurology and the mental health fields of Psychiatry, Psychology and Social Work, preferably early in the diagnostic process. If this critical connection to mental health resources is delayed, patients risk poor prognosis for their recovery as well as continuing exposure to iatrogenic complications.

Credibility of the v-EEG-established diagnosis can be quite disparate between the disciplines involved in the diagnosis versus the care of PNES patients. Among neurologists, the inter-rater reliability for video-EEG diagnosis of PNES is only moderate.58 When the disciplines of Neurology and Psychiatry were surveyed with regard to how much they “believed” the v-EEG diagnosis of PNES, 70% of neurologists, but only 18% of psychiatrists, answered “most of the time.”59 There is certainly a need to “build bridges” between these disciplines and, in particular, to educate mental health professionals in order to help patients be properly diagnosed and receive the timely treatment they need.

Conclusion

Despite recognition of PNES as a clinical entity in the 19th century, the field of PNES has advanced quite slowly. Only recently there has been a renewed interest leading to a few pilot randomized clinical trials. At the practical level, the interdisciplinary involvement and collaboration of neurologists and mental health professionals is the central piece that facilitates proper care delivery to this population. While it is tempting to hope that there will be effective treatments for PNES that will render symptom remission, thinking about phases of treatment in PNES may help guide clinicians who encounter patients at different time points of their illness. Engagement in treatment is a first pivotal part in the management of the disorder. Acute treatment interventions for PNES have been studied in few randomized controlled trials and continue to be the focus of investigation. CBT has demonstrated efficacy and warrants further examination. Within the discussion of acute treatment interventions for PNES, we presented preliminary findings from a case series on a mindfulness-based intervention, which is a feasible form of treatment in clinical settings and should be considered as a psychotherapeutic modality worth further investigation in larger scale studies. Many of the principles behind these two forms of psychotherapy (CBT and mindfulness-based psychotherapy) overlap and are complementary rather than contradictory. Finally, there is considerable evidence indicating that a sizable proportion of PNES patients will remain symptomatic. Long-term interventions have not been systematically studied and should be explored, since they may help those patients with chronic symptoms. While patients’ psychopathology may cause challenges in the treatment, providers also need to improve their interdisciplinary collaborative efforts and recognize and embrace their role in treatment. As we understand more about PNES treatment, guidelines may emerge that eventually guide clinicians on how to approach PNES patients at different phases of their disease.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Dr. David L. Perez was funded by a NINDS R25 NS065743-05S1 grant.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th edition. Arlington VA: American Psychiatric Publishing; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carson AJ, Brown R, David AS, Duncan R, Edwards MJ, Goldstein LH, Grunewald R, Howlett S, Kanaan R, Mellers J, Nicholson TR, Reuber M, Schrag AE, Stone J, Voon V. UK-FNS. Functional (conversion) neurological symptoms: research since the millennium. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2012;83(8):842–850. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2011-301860. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reuber M, Fernandez G, Bauer J, Helmstaedter C, Elger C. Diagnostic delay in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Neurology. 58:493–495. doi: 10.1212/wnl.58.3.493. 2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reuber M. Psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: answers and questions. Epilepsy Behav. 2008;12(4):622–635. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goetz CG. Charcot and Psychogenic Movement Disorders. In: Hallett M, Fahn S, Jankovic J, Lang AE, Cloninger CR, Yudofsky SC, editors. Psychogenic Movement Disorders: Neurology and Psychiatry. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2006. pp. 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tomlinson WC. Freud and Psychogenic Movement Disorders. In: Hallett M, Fahn S, Jankovic J, Lang AE, Cloninger CR, Yudofsky SC, editors. Psychogenic Movement Disorders: Neurology and Psychiatry. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2006. pp. 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perez D, Barsky A, Daffner K, Silbersweig D. Motor and somatosensory conversion disorder: A functional unawareness syndrome? Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2012;24:141–151. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.11050110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.LaFrance W, Alper K, Babcock D, Barry J, Benbadis S, Caplan R, Gates J, Jacobs M, Kanner A, Martin R, Rundhaugen L, Stewart R, Vert C. Nonepileptic seizures treatment workshop summary. Epilepsy & Behavior. 2006;8:451–461. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2006.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Uliaszek AA, Prensky E, Baslet G. Emotion regulation profiles in psychogenic non-epileptic seizures. Epilepsy Behav. 2012;23(3):364–369. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2012.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baslet G. Psychogenic non-epileptic seizures: A model of their pathogenic mechanism. Seizure. 2011;20:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2010.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szaflarski J, Szaflarski M, Hughes C, Ficker D, Cahill W, Privitera M. Psychopathology and quality of life: psychogenic non-epileptic seizures versus epilepsy. Medical Science Monitor. 2003;9(4):113–118. 2003. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Reuber M, Baker G, Gill R, Smith D, Chadwick D. Failure to recognise psychogenic nonepileptic seizures may cause death. Neurology. 2004;62:834–835. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000113755.11398.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walczak T, Papacostas S, Williams D, Scheuer M, Lebowitz N, Notarfrancesco A. Outcome after diagnosis of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsia. 1995;36:1131–1137. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1157.1995.tb00472.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Durrant J, Rickards H, Cavanna AE. Prognosis and outcome predictors in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsy Res Treat. 2011;2011:274736. doi: 10.1155/2011/274736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.LaFrance W, Rusch M, Machan J. What is "treatment as usual" for nonepileptic seizures? Epilepsy & Behavior. 2008;12:388–394. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2007.12.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kanner AM. Is the neurologist's role over once the diagnosis of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures is made? No! Epilepsy Behav. 2008;12:1–2. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2007.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baslet G, Roiko A, Prensky E. Heterogeneity in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: understanding the role of psychiatric and neurological factors. Epilepsy & Behavior. 2010;17:236–241. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duncan R, Razvi S, Mulhern S. Newly presenting psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: Incidence, population characteristics, and early outcome from a prospective audit of a first seizure clinic. Epilepsy & Behavior. 2011;20:308–311. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2010.10.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hall-Patch L, Brown R, House A, Howlett S, Kemp S, Lawton G, Mayor R, Smith P, Reuber M. Acceptability and effectiveness of a strategy for the communication of the diagnosis of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsia. 2010;51:70–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Baslet G. Psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: a treatment review. What have we learned since the beginning of the millennium? Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2012;8:585–598. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S32301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Baslet G, Prensky E. Initial treatment retention in psychogenic non-epileptic seizures. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013 Winter;25(1):63–67. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.11090223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lundahl B, Moleni T, Burke BL, Butters R, Tollefson D, Butler C, Rollnick S. Motivational interviewing in medical care settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Patient Educ Couns. 2013 Nov;93(2):157–168. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2013.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goldstein L, Chalder T, Chigwedere C, Khondoker M, Moriarty J, Toone B, Mellers J. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: A pilot RCT. Neurology. 2010;74:1986–1994. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181e39658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.LaFrance WC, Jr, Baird GL, Barry JJ, Blum AS, Frank Webb A, Keitner GI, Machan JT, Miller I, Szaflarski JP for the NES Treatment Trial (NEST-T) Consortium. Multicenter Pilot Treatment Trial for Psychogenic Nonepileptic Seizures: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2014 Jul 2; doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.817. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.LaFrance W, Miller I, Ryan C, Slum A, Solomon D, Kelley J, Keitner G. Cognitive behavioral therapy for psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsy & Behavior. 2009;14:591–596. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2009.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kuyk J, Siffels M, Bakvis P, Swinkels W. Psychological treatment of patients with psychogenic non-epileptic seizures: An outcome study. Seizure. 2008;17:595–603. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2008.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Conwill M, Oakley L, Evans K, Cavanna AE. CBT-based group therapy intervention for nonepileptic attacks and other functional neurological symptoms: A pilot study. Epilepsy Behav. 2014 May;34:68–72. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2014.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen DK, Maheshwari A, Franks R, Trolley GC, Robinson JS, Hrachovy RA. Brief group psychoeducation for psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: a neurologist-initiated program in an epilepsy center. Epilepsia. 2014 Jan;55(1):156–166. doi: 10.1111/epi.12481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ataoglu A, Ozcetin A, Icmeli C, Ozbulut O. Paradoxical therapy in conversion reaction. J Korean Med Sci. 2003 Aug;18(4):581–584. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2003.18.4.581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moene FC1, Spinhoven P, Hoogduin KA, van Dyck R. A randomised controlled clinical trial on the additional effect of hypnosis in a comprehensive treatment programme for in-patients with conversion disorder of the motor type. Psychother Psychosom. 2002 Mar-Apr;71(2):66–76. doi: 10.1159/000049348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Moene FC1, Spinhoven P, Hoogduin KA, van Dyck R. A randomized controlled clinical trial of a hypnosis-based treatment for patients with conversion disorder, motor type. Int J Clin Exp Hypn. 2003 Jan;51(1):29–50. doi: 10.1076/iceh.51.1.29.14067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mayor R, Howlett S, Grünewald R, Reuber M. Long-term outcome of brief augmented psychodynamic interpersonal therapy for psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: Seizure control and health care utilization. Epilepsia. 2010;51:1169–1176. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2010.02656.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Barry JJ, Wittenberg D, Bullock KD, Michaels JB, Classen CC, Fisher RS. Group therapy for patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: a pilot study. Epilepsy Behav. 2008;13(4):624–629. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2008.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Prigatano G, Stonnington C, Fisher R. Psychological factors in the genesis and management of nonepileptic seizures: Clinical observations. Epilepsy & Behavior. 2002;3:343–349. doi: 10.1016/s1525-5050(02)00053-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zaroff C, Myers L, Barr W, Luciano D, Devinsky O. Group psychoeducation as treatment for psychological nonepileptic seizures. Epilepsy & Behavior. 2004;5:587–592. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2004.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mayor R, Brown R, Cock H, House A, Howlett S, Smith P, Reuber M. A feasibility study of a brief psycho-educational intervention for psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Seizure. 2013;22:760–765. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2013.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.LaFrance W, Keitner G, Papandonatos G, Blum A, Machan J, Ryan C, Miller I. Pilot pharmacologic randomized controlled trial for psychogenic nonepileptic seizures. Neurology. 2010;75:1166–1173. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181f4d5a9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pintor L, Bailles E, Matrai S, Carreno M, Donaire A, Boget T, Setoain X, Rumia J, Bargalló N. Efficiency of venlafaxine in patients with psychogenic nonepileptic seizures and anxiety and/or depressive disorders. Journal of Neuropsychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences. 2010;22:401–408. doi: 10.1176/jnp.2010.22.4.401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Martlew J, Pulman J, Marson AG. Psychological and behavioural treatments for adults with non-epileptic attack disorder. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014 Feb 11;2:CD006370. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006370.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hofmann S, Sawyer A, Witt A, Oh D. The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2010;78:169–183. doi: 10.1037/a0018555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Skanavi S, Laqueille X, Aubin HJ. Mindfulness based interventions for addictive disorders: a review (in French) Encephale. 2011;37:379–387. doi: 10.1016/j.encep.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kabat-Zinn J. Full catastrophe living: Using the wisdom of your body and mind to face stress, pain, and illness. New York, NY: Delacorte; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hayes S, Strosahl K, Wilson K. Acceptance and commitment therapy. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Linehan M. Cognitive-behavioral treatment of borderline personality disorder. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Segal Z, Williams J, Teasdale J. Mindfulness-based cognitive therapy for depression: A new approach to preventing relapse. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Baslet G, Hill J. Case report: Brief mindfulness-based psychotherapeutic intervention during inpatient hospitalization in a patient with conversion and dissociation. Clinical Case Studies. 2011;10:95–109. [Google Scholar]

- 47.LaFrance WC, Jr, Baker GA, Duncan R, Goldstein LH, Reuber M. Minimum requirements for the diagnosis of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: a staged approach: a report from the International League Against Epilepsy Nonepileptic Seizures Task Force. Epilepsia. 2013;54:2005–2018. doi: 10.1111/epi.12356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kanner A, Parra J, Frey M, Stebbins G, Pierre-Louis S, Iriarte J. Psychiatric and neurologic predictors of psychogenic pseudoseizure outcome. Neurology. 1999;53:933–938. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.5.933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.McKenzie P, Oto M, Russell A, Pelosi A, Duncan R. Early outcomes and predictors in 260 patients with psychogenic nonepileptic attacks. Neurology. 2010 Jan 5;74(1):64–69. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c7da6a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McKenzie PS, Oto M, Graham CD, Duncan R. Do patients whose psychogenic non-epileptic seizures resolve, 'replace' them with other medically unexplained symptoms? Medically unexplained symptoms arising after a diagnosis of psychogenic non-epileptic seizures. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2011 Sep;82(9):967–969. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2010.231886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Razvi S, Mulhern S, Duncan R. Newly diagnosed psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: Health care demand prior to and following diagnosis at a first seizure clinic. Epilepsy & Behavior. 2012;23:7–9. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2011.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jirsch J, Ahmed S, Maximova K, Gross D. Recognition of psychogenic nonepileptic seizures diminishes acute care utilization. Epilepsy & Behavior. 2011;22:304–307. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2011.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Duncan R, Graham CD, Oto M, Russell A, McKernan L, Copstick S. Primary and secondary care attendance, anticonvulsant and antidepressant use and psychiatric contact 5–10 years after diagnosis in 188 patients with psychogenic non-epileptic seizures. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2014 Jan 20; doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2013-306671. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Reuber M, Pukrop R, Bauer J, Helmstaedter C, Tessendorf N, Elger CE. Outcome in psychogenic nonepileptic seizures: 1 to 10-year follow-up in 164 patients. Ann Neurol. 2003 Mar;53(3):305–311. doi: 10.1002/ana.3000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Carton S, Thompson PJ, Duncan JS. Non-epileptic seizures: patients' understanding and reaction to the diagnosis and impact on outcome. Seizure. 2003 Jul;12(5):287–294. doi: 10.1016/s1059-1311(02)00290-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Goldstein L, Mellers J. Ictal symptoms of anxiety, avoidance behaviour, and dissociation in patients with dissociative seizures. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery, and Psychiatry. 77:616–621. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2005.066878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Goldstein L, Drew C, Mellers J, Mitchell-O’Malley S, Oakley D. Dissociation, hypnotizability, coping styles, and health locus of control: Characteristics of pseudoseizure patients. Seizure. 2000;9:314–322. doi: 10.1053/seiz.2000.0421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Benbadis S, LaFrance W, Papandonatos G, Korabathina K, Lin K, Kraemer H. Interrater reliability of EEG-video monitoring. Neurology. 2009;73:843–846. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181b78425. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Harden C, Burgut F, Kanner A. The diagnostic significance of video-EEG monitoring findings on pseudoseizure patients differs between neurologists and psychiatrists. Epilepsia. 2003;44:453–456. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2003.33002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]