Abstract

There are abundant studies indicating that blocking gap junctions (GJs) containing connexin 36 (Cx36) inhibit seizures. However, recent evidences demonstrate proconvulsant effect of such intervention. Electrical coupling between GABAergic interneurons in CA1 region of hippocampus is mediated through Cx36 GJs. We investigated effect of quinine, a specific blocker of Cx36, on the seizure severity and epileptogenesis in amygala kindling model of epilepsy in rats. Quinine (1, 50, 100, 500 and 2000 µM/rat) was injected directly into the CA1 and kindled seizure parameters including behavioral seizure stage, duration of evoked afterdischarges, and duration of generalized seizures behavior were recorded 10 min afterward. Moreover, quinine (1, 30, and 100 µM/rat) was injected intra CA1 once daily during kindling development. At the doses used, quinine had no significant effect on amygdala-kindled seizures. However, quinine 100 µM significantly accelerated kindling rate. Blockade of Cx36 GJs coupling and consequent disruption of inhibitory transmission in GABAergic interneurons in CA1 area seems to be responsible for the antiepileptogenic effect of quinine.

Keywords: Cx36, CA1, amygdala kindling, quinine

Introduction

Epilepsy, which is characterized by recurrent seizures, is one of the most common neurological disorders in the world. Abnormal synchronization of neuronal discharges plays critical role in seizures (Carlen et al., 2000[5]). Besides chemical synapses, direct coupling via gap junction (GJ) channels provides a second major pathway contributing to pathologic neuronal synchronous firing in various in vitro (Ross et al., 2000[29]; Köhling et al., 2001[16]; Traub et al., 2001[33]; Jahromi et al., 2002[14]) and in vivo (Perez-Velazquez et al., 1994[27]; Szente et al., 2002[32]; Traub et al., 2002[35]; Gajda et al., 2003[10]) seizure models. Each GJ channel consists of two hemichannels termed connexon, each of which is composed of six subunit proteins called connexin (Cx). Progressive understanding of the role of GJs in neuronal synchronization and generation of epileptic discharges has led to the identification of Cxs as potential molecular targets for development of antiepileptic drugs (Meldrum and Rogawski, 2007[22]).

Temporal lobe structures and notably hippocampus are among most susceptible regions involved in acquisition of epilepsies and therefore temporal lobe epilepsy is the most common form of epilepsy (Wiebe, 2000[41]). There is strong evidence that GJs play a role in the fast oscillations that precede the onset of seizures discharges in the hippocampus (LeBeau et al., 2003[17]; Traub et al., 2011[34]). In CA1 subfield of the hippocampus, paravalbumin positive GABAergic interneurons form a vast dendrodendritic network, which is responsible for synchronized oscillations in hippocampus and thereby promote inhibitory transmission (Fukuda and Kosaka, 2000[9]). Morphological (Fukuda and Kosaka, 2000[9]; Baude et al., 2007[1]) and electrophysiological (Venance et al., 2000[36]) evidence indicate that electrical coupling between GABAergic interneurons in this region is mediated by Cx36. Hence, it might be anticipated that enhancement of Cx36 GJ communication (GJC) in this region can reinforce the inhibitory circuit and thereby limit neuronal hyperexcitability and propagation of abnormal discharges to the neighboring areas. This assumption is supported by the recent finding of Jacobson et al. (2010[13]) that Cx36 knockout mice has a markedly lowered seizure threshold for generalized tonic-clonic seizures compared to wild type animals. Furthermore, pharmacologic blockade of Cx36 GJs induces an excitatory effect on seizure-like activity in rat cortical slices (Voss et al., 2009[37]).

Quinine, the old anti-malaria drug, is the only available specific blocker of Cx36 (Srinivas et al., 2001[31]), which is currently used as a pharmacologic tool in research on the function of Cx36 in seizures' mechanisms. Quinine suppresses ictal epileptiform activity in vitro without decreasing neuronal excitability (Bikson et al., 2002[3]). Quinine has anticonvulsive effect at the already active epileptic focus and suppresses seizure activity in rat neocortex in vivo (Gajda et al., 2005[11]). It also decreases amplitude and frequency of epileptiform spikes in penicillin model of epilepsy (Bostanci and Bagirici, 2007[4]). Quinine protects mice and rats against PTZ-induced seizures (Nassiri-Asl et al., 2008[24], 2009[23]). Moreover, quinine injection into the entorhinal cortex of seizing rats has diminished the frequency and amplitude of the discharges in the hippocampus (Medina-Ceja and Ventura-Mejía, 2010[21]). In contrast, quinine has proconvulsant effect on rat cortical slices (Voss et al., 2009[37]). Moreover, transgenic mice lacking Cx36 are seizure prone (Jacobson et al., 2010[13]). Cx36 blockade has been ineffective in reducing seizure-like activity in neocortical mouse slices (Voss et al., 2010[39]). In spite of these extensive in vitro and in vivo investigations, role of Cx36 containing GJs present in CA1 area of the hippocampus, in seizure initiation and development of epilepsy is not directly evaluated.

In this study, we examined effect of intra-CA1 injection of quinine, on amygdala-kindled seizures. Furthermore, impact of Cx36 blockade on acquisition of kindled seizures (epileptogenesis) was also examined.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male Wistar rats (270-320 g, Pasteur Institute of Iran) were used throughout this study. The animals were housed in standard Plexiglas cages with free access to food (standard laboratory rodent's chow) and water. The animal house temperature was maintained at 23 ± 1 °C with a 12 h light/dark cycle (light on from 6.00 AM). Animal experiments protocol was approved by the Review Board and Ethics Committee of Pasteur Institute and conformed to European Communities Council Directive of November 1986 (86/609/EEC).

Stereotaxic surgery and kindling procedure

The rats were anesthetized with intra-peritoneal (i.p.) injection of 60 mg/kg ketamine (Rotex Medica, Germany) and 10 mg/kg xylazine (Candelle, Ireland). The animals were then stereotaxically implanted with bipolar stimulating and monopolar recording stainless-steel Teflon-coated electrodes (A.M. Systems, USA, twisted into a tripolar configuration), in the basolateral amygdala (coordinates: A, -2.5 mm from bregma; L, 4.8 mm from bregma and V, 7.3 mm from dura) of the right hemisphere (Paxinos and Watson, 2005[26]). An injection guide-cannula was also implanted into the CA1 area of right hippocampus (coordinates: A, −3.8; L, −2.3 and V, 2.4 mm from dura). The electrodes and cannula were fixed to the skull with dental acrylic. The animals were given 7 days for recovery after surgery, before the kindling protocol was started. One week after surgery, afterdischarge (AD) threshold was determined in amygdala by a 2-Sec, 100-Hz monophasic square-pulse stimulus of 1 mSec per pulse. The stimulation was initially delivered at 50 µA and then at 5-min intervals, increasing stimulus intensity in increments of 50 µA was delivered, until at least 5 Sec of AD was recorded (Beheshti et al., 2010[2]). Then, the animals were stimulated at AD threshold once daily until three consecutive stage 5 seizures were elicited according to Racine classification as stage 1, facial clonus; stage 2, head nodding; stage 3, forelimb clonus; stage 4, rearing and bilateral forelimb clonus; stage 5, rearing, loss of balance and falling (Racine, 1972[28]). These animals were then considered fully kindled. Quinine (hemisulfate salt monohydrate, Sigma-Aldrich) and artificial cerebrospinal fluid (aCSF with composition (in mM) of 124.0 NaCl, 25 NaHCO3, 10 D-glucose, 4.4 KCl, 2 MgSO4, 1.25 KH2PO4, and 2 CaCl2) were infused (1 µl in 5 min) into CA1 by a 27-gauge cannula, which was extended 1 mm below the tip of guide cannula.

Effect of intra-CA1 injection of quinine on kindled seizures

Quinine at doses of 1, 50, 100, 500, and 2000 µM/rat was infused into CA1 of 5 groups of kindled rats (n=7) and after 10 and 30 min time intervals, amygdala was stimulated at AD threshold. This time point was selected based on previous report indicating that peak effect of quinine appears 10 min after cerebral application (Gajda et al., 2005[11]). AD duration (ADD), behavioral seizure severity (SS), and duration of stage 5 seizure behavior (S5D) were then measured in each animal. The animals served as their own control groups; i.e. the rats received aCSF intra-CA1 24 h before quinine administration, and evoked seizure parameters were recorded at above mentioned time intervals.

Effect of intra-CA1 injection of quinine on kindling rate

Twenty-four h after determination of AD threshold, the rats were divided into four groups of seven rats in each. They received quinine (1, 30, and 100 µM/rat, intra-CA1) or aCSF (1 µl/rat, intra-CA1) once daily. Daily electrical stimulation was delivered 10 min before quinine or aCSF injections until the animals became fully kindled. SS and ADD were recorded after each stimulation.

Histology

At the end of the experiments, the brains were removed, processed, cut into 50-µm thick slices and stained by the method previously described (Beheshti et al. 2010[2]). Stained slices were qualitatively analyzed for cannula and electrode positions and also any lesion, using a stereoscopic microscope (Olympus, Japan) and a light microscope (Zeiss, Germany). The data of the animals, in which the cannula and electrode were in false placement, were not included in the results.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented as mean ± SEM. If data had a normal distribution, they were analyzed by parametric test (ANOVA with repeated measures for post hoc analysis). Otherwise, the data were analyzed by nonparametric test (Kruskal-Wallis analysis of variance). In all experiments, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

The mean AD threshold obtained for the animals was in the range of 50-150 µA. Histological evaluation of the brains confirmed correct position of the electrode and cannula in all of the animals.

Quinine had no effect on fully kindled seizures

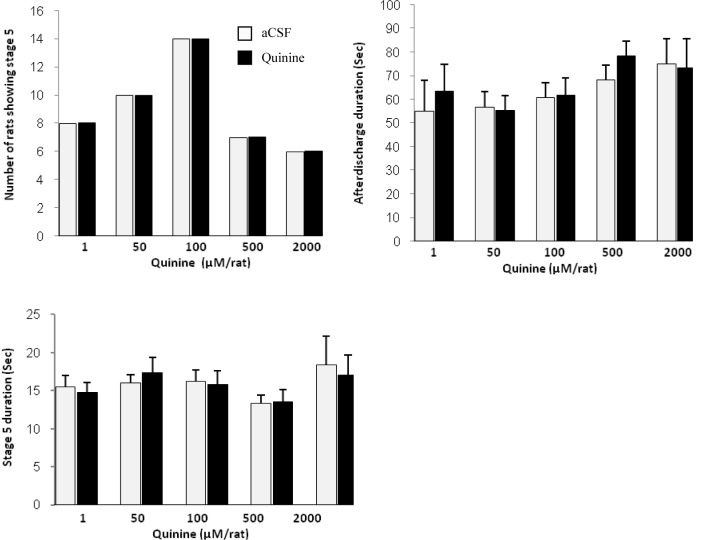

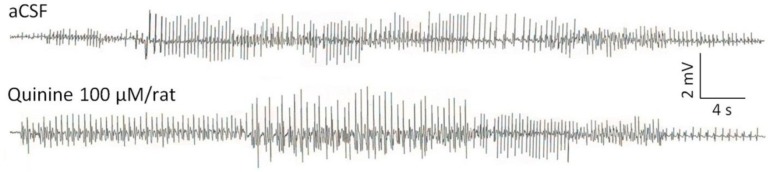

Neither of the applied doses of quinine affected kindled seizure parameters at 10 and 30 min post administration periods. Figures 1(Fig. 1) and 2(Fig. 2) show the results of 10 min post administration period.

Figure 1. Effect of quinine on afterdischarges recorded from amygdala of a kindled rat 10 minutes after intra-CA1 administration.

Figure 2. Effect of quinine on kindled seizures 10 minutes after intra-CA1 injection to rats. Values are mean ± SEM.

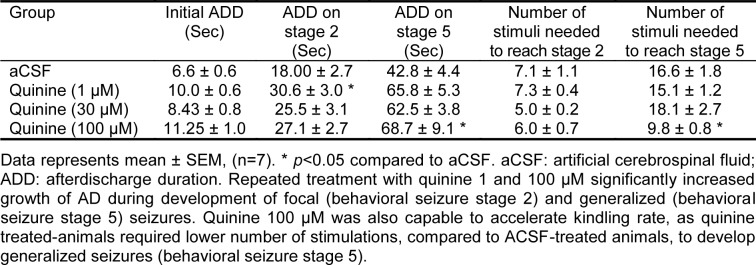

Quinine accelerates development of kindling

All doses of quinine increased growth of AD during kindling development (Table 1(Tab. 1)). Quinine 1 µM caused a 1.5 fold increase in ADD at the time of focal seizures acquisition (behavioral seizure stage 2) compared to control group. Chronic administration of quinine 100 µM resulted in 1.5 fold enhancement in ADD when the animals became fully kindled (showed stage 5). Furthermore, at the dose of 100 µM the animals need lower number of stimuli to reach the kindled state.

Table 1. Effects of daily intra-CA1 injection of quinine on development of kindling.

Discussion

Results of the present study indicate that blockade of GJs composed of Cx36 in the CA1 area of the rat hippocampus accelerates progression of kindling but does not affect kindled seizures.

Most in vivo studies on the effect of quinine on seizures have been performed in 4-aminopyridine (4-AP) model of epilepsy (Gajda et al., 2005[11]; Medina-Ceja and Ventura-Mejía, 2010[21]). The 4-AP model can be regarded as semi-chronic epilepsy model, as its specific feature is prolonged epileptiform activity in a manner that at least 25 seizures occur spontaneously during a 60-min period (Gajda et al., 2005[11]). This specificity enables investigator to apply the investigating drug during seizures and observe the effect of drug on active state of GJs. In hyperexcitable conditions, conformation of GJ channels changes to active state, and results in increase electrical communication between adjacent cells (Sáez et al., 2010[30]). This might in turn cause more efficient binding of quinine to Cx36 and therefore more functional blockade. However, in cases of acute seizures such as kindled seizures, duration of epileptic activity is not as long as that in 4-AP model. Therefore, quinine can not bind effectively to the Cx36. This assumption might be the reason of ineffectiveness of quinine on kindled seizures.

In our study, the rats which received quinine 100 µM, the dose which maximally blocks Cx36 GJs (Srinivas et al., 2001[31]), developed generalized seizures much earlier than control rats. In the kindling model, the behavioral seizure stages 1, 2, and 3 most often originate from foci within the limbic system and are considered as focal seizures, while behavioral stages 4 and 5 represent secondary generalized motor seizures (Racine, 1972[28]). Our finding suggests that Cx36 GJs have a critical role in kindling epileptogenesis and inhibit seizure propagation from limbic focus to the rest of the brain and consequent generalizations of the seizures. This result is in agreement with our previous finding that gene and protein of hippocampal Cx36 are over-expressed during amygdala kindling (Beheshti et al., 2010[2]).

Apart from hippocampus, Cx36 is also present in the mature cerebral cortex as the most common neuronal Cx, and its expression appears to be restricted almost exclusively to a subclass of inhibitory interneurons, parvalbumin-containing basket cells (Deans et al., 2001[8]; Liu and Jones, 2003[18]; Markram et al., 2004[19]). Interestingly, blocking of cortical Cx36 GJs by quinine significantly reinforces both the frequency and amplitude of seizure-like activity in rat cerebral cortex (Voss et al., 2009[37]). Closing Cx36 GJs and consequent disinhibitory effect on pyramidal cell activity is suggested to be involved in this proconvulsant effect of quinine. Moreover, it has been shown that knockout of Cx36 promotes epileptic hyperexcitability (Pais et al., 2003[25]) and decreases threshold of generalized tonic-clonic seizures induced by PTZ (Jacobson et al., 2010[13]). These results together with our finding in the present study confirm that Cx36 GJs, present in GABAergic interneuron network, play a critical role in inhibitory control of excitatory runaway activity (Jacobson et al., 2010[13]). In contrast to these results, it has been reported that the blockade of Cx36 GJC attenuates seizures in some epilepsy models. Application of quinine significantly decreases duration of the seizures induced by 4-AP (Gajda et al., 2005[11]). Quinine acts as an antiepileptic drug in penicillin model of cortical seizures (Bostanci and Bagirici, 2007[4]). Moreover, quinine significantly decreases duration of PTZ-induced seizures in a dose-dependent manner (Nassiri-Asl et al., 2009[23]). Likewise, injection of quinine into the entorhinal cortex decreases amplitude and frequency of epileptic discharges in seizing rats (Medina-Ceja and Ventura-Mejía, 2010[21]). Two explanations can be suggested for the paradoxical effects of quinine on seizures; 1) Different models of seizures with different mechanisms of action have been used in these studies. For instance, in 4-AP model, blockade of K+ channels as well as glutamate release, promote convulsions (Medina-Ceja and Ventura-Mejía, 2010[21]). Penicillin induces seizures due to its similar structure to GABAA receptor antagonist bicuculline (Bostanci and Bagirci, 2007[4]). On the other hand, Voss et a. (2009[37]) induced seizure-like activity by perfusion of cerebral cortical slices with low magnesium aCSF. In the present study, we used kindling model of epilepsy in which glutamatergic and GABAergic neurotransmission are involved in seizure manifestation. Therefore, it can be postulated that anticonvulsant or proconvulsant effect of quinine observed in the different studies, depends on the level of involvement of chemical or electrical synapses in the particular epilepsy model used in each study. Here, we directly applied quinine into the CA1 area. CA1 pyramidal cells are involved in generalization of amygdala kindled seizures (Hewapathirane and Burnham, 2005[12]). It seems that spread of activity within the inhibitory circuit in CA1 area is decreased by quinine, which in turn amplifies seizure propagation to outside of hippocampus. However, in other studies with opposite findings, the Cx36 GJs present in inhibitory circuit, might not be affected in this manner. 2) In the reports regarding anticonvulsant effect of quinine, a wide range of doses has been used. Although quinine is a specific blocker of Cx36 GJ (EC50 = 32 µM, maximal blockade at 100 µM) (Srinivas et al., 2001[31]), it can also block Cx45 (EC50 = 300 µM), IP3-induced Ca2+ release (EC50 = 250 µM), Cx50 (EC50 = 73 µM), Sodium currents (EC50 > 20 µM), voltage-dependent K+ channels (EC50 = 8 µM), ATP-sensitive K+ channels (EC50 = 3 µM) and nicotinic receptors (EC50 = 1 µM) (Juszczak and Swiergiel, 2009[15]). Therefore, the possibility exists that the anticonvulsant effect of quinine observed in the other studies may be related to the off-target actions of this agent.

It has recently been reported that long term potentiation (LTP) is reduced in the hippocampal CA1 region of Cx36 knockout mice (Wang and Belousov, 2011[40]). Kindling is a model of epileptogenesis and synaptic plasticity, in which LTP of synaptic transmission occurs (McNamara et al., 1980[20]). According to our results, blocking Cx36 GJs in CA1 region facilitates epileptogenesis and therefore LTP. Our finding appears to be in contrast to finding of Wang and Belousov (2011[40]). However, it has been well documented that Cx36 knockout mice have an increased GABAergic tone as a compensation for their lack of interneuron GJs, which results in enhancement of feedback inhibition (De Zeeuw et al., 2003[7]; Cummings et al., 2008[6]; Voss et al., 2010[38]). Hence, reduction of hippocampal LTP in mice lacking Cx36 might not be necessarily mediated by lack of interneuronal GJs, rather by compensatory overactivity of GABAergic interneurons.

In conclusion, we found that chronic intra-CA1 injection of quinine, at the dose of 100 µM, which specifically blocks Cx36 GJs, facilitates epileptogenesis by acceleration of kindling development. Cx36 can be considered as a molecular target in prevention of epilepsy. Due to possible confusing effect made by compensatory neurophysiological changes in knockout animals, design and availability of specific Cx36 GJ openers are needed to further clarify Cx36 GJs potential for antiepileptic drugs development.

References

- 1.Baude A, Bleasdale C, Dalezios Y, Somogyi P, Klausberger T. Immunoreactivity for the GABA-A receptor alpha1 subunit, somatostatin and connexin36 distinguishes axoaxonic, basket and bistratified interneurons of the rat hippocampus. Cereb Cortex. 2007;17:2094–107. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhl117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Beheshti S, Sayyah M, Golkar M, Sepehri H, Babaie J, Vaziri B. Changes in hippocampal connexin36 mRNA and protein levels during epileptogenesis in the kindling model of epilepsy. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2010;34:510–515. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bikson M, Id Bihi R, Vreugdenhil M, Köhling R, Fox JE, Jefferys JG. Quinine suppresses extracellular potassium transients and ictal epileptiform activity without decreasing neuronal excitability in vitro. Neuroscience. 2002;115:251–61. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00320-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bostanci MO, Bagirici F. Anticonvulsive effects of quinine on penicillin-induced epileptiform activity: an in vivo study. Seizure. 2007;16:166–72. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carlen PL, Skinner F, Zhang L, Naus C, Kushnir M, Perez Velazquez JL. The role of gap junctions in seizures. Brain Res Rev. 2000;32:235–41. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0173(99)00084-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cummings DM, Yamazaki I, Cepeda C, Paul DL, Levine MS. Neuronal coupling via connexin36 contributes to spontaneous synaptic currents of striatal medium-sized spiny neurons. J Neurosci Res. 2008;86:2147–2158. doi: 10.1002/jnr.21674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.De Zeeuw CI, Chorev E, Devor A, Manor Y, Van Der Giessen RS, De Jeu MT, et al. Deformation of network connectivity in the inferior olive of connexin 36-deficient mice is compensated by morphological and electrophysiological changes at the single neuron level. J Neurosci. 2003;23:4700–4711. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-11-04700.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Deans MR, Gibson JR, Sellitto C, Connors BW, Paul DL. Synchronous activity of inhibitory networks in neocortex requires electrical synapses containing connexin36. Neuron. 2001;31:477–85. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(01)00373-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fukuda T, Kosaka T. Gap junctions linking the dendritic network of GABAergic interneurons in the hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2000;20:1519–1528. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-04-01519.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gajda Z, Gyengési E, Hermesz E, Ali KS, Szente M. Involvement of gap junctions in the manifestation and control of the duration of seizures in rats in vivo. Epilepsia. 2003;44:1596–600. doi: 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2003.25803.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gajda Z, Szupera Z, Blazsó G, Szente M. Quinine, a blocker of neuronal Cx36 channels, suppresses seizure activity in rat neocortex in vivo. Epilepsia. 2005;46:1581–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2005.00254.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hewapathirane DS, Burnham WM. Propagation of amygdala-kindled seizures to the hippocampus in the rat: electroencephalographic features and behavioural correlates. Neurosci Res. 2005;53:369–375. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2005.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jacobson GM, Voss LJ, Melin SM, Mason JP, Cursons RT, Steyn-Ross AD, et al. Connexin36 knockout mice display increased sensitivity to pentylenetetrazole-induced seizure-like behaviors. Brain Res. 2010;1360:198–204. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jahromi SS, Wentlandt K, Piran S, Carlen PL. Anticonvulsant actions of gap junctional blockers in an in vitro seizure model. J Neurophysiol. 2002;88:1893–902. doi: 10.1152/jn.2002.88.4.1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Juszczak GR, Swiergiel AH. Properties of gap junction blockers and their behavioural, cognitive and electrophysiological effects: animal and human studies. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2009;33:181–198. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2008.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Köhling R, Gladwell SJ, Bracci E, Vreugdenhil M, Jefferys JG. Prolonged epileptiform bursting induced by 0-Mg2+ in rat hippocampal slices depends on gap junctional coupling. J Neurosci. 2001;105:579–87. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00222-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.LeBeau FE, Traub RD, Monyer H, Whittington MA, Buhl EH. The role of electrical signaling via gap junctions in the generation of fast network oscillations. Brain Res Bull. 2003;62:3–13. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2003.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu XB, Jones EG. Fine structural localization of connexin-36 immunoreactivity in mouse cerebral cortex and thalamus. J Comp Neurol. 2003;466:457–467. doi: 10.1002/cne.10901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Markram H, Toledo-Rodriguez M, Wang Y, Gupta A, Silberberg G, Wu C. Interneurons of the neocortical inhibitory system. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5:793–807. doi: 10.1038/nrn1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McNamara JO, Byrne MC, Dasheiff RM, Fitz JG. The kindling model of epilepsy: a review. Prog Neurobiol. 1980;15:139–59. doi: 10.1016/0301-0082(80)90006-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Medina-Ceja L, Ventura-Mejía C. Differential effects of trimethylamine and quinine on seizures induced by 4-aminopyridine administration in the entorhinal cortex of vigilant rats. Seizure. 2010;19:507–513. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2010.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Meldrum BS, Rogawski MA. Molecular targets for antiepileptic drug development. Neurotherapeutics. 2007;4:18–61. doi: 10.1016/j.nurt.2006.11.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nassiri-Asl M, Zamansoltani F, Torabinejad B. Antiepileptic effects of quinine in the pentylenetetrazole model of seizure. Seizure. 2009;18:129–32. doi: 10.1016/j.seizure.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nassiri-Asl M, Zamansoltani F, Zangivand AA. The inhibitory effect of trimethylamine on the anticonvulsant activities of quinine in the pentylenetetrazole model in rats. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32:1496–1500. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pais I, Hormuzdi SG, Monyer H, Traub RD, Wood IC, Buhl EH, et al. Sharp wave-like activity in the hippocampus in vitro in mice lacking the gap junction protein connexin 36. J Neurophysiol. 2003;89:2046–2054. doi: 10.1152/jn.00549.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. New York: Academic Press; 2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perez-Velazquez JL, Valiante TA, Carlen PL. Modulation of gap junctional mechanisms during calcium-free induced field burst activity: a possible role for electrotonic coupling in epilepsy. J Neurosci. 1994;14:4308–17. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-07-04308.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Racine RJ. Modification of seizure activity by electrical stimulation II: motor seizure. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1972;32:281–94. doi: 10.1016/0013-4694(72)90177-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ross FM, Gwyn P, Spanswick D, Davies SN. Carbenoxolone depresses spontaneous epileptiform activity in the CA1region of rat hippocampal slices. J Neurosci. 2000;100:789–96. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(00)00346-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sáez JC, Schalper KA, Retamal MA, Orellana JA, Shoji KF, Bennett MV. Cell membrane permeabilization via connexin hemichannels in living and dying cells. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316:2377–2389. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Srinivas M, Hopperstad MG, Spray DC. Quinine blocks specific gap junction channel subtypes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:10942–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.191206198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Szente M, Gajda Z, Said KA, Hermesz E. Involvement of electrical coupling in the in vivo ictal epileptiform activity induced by 4-aminopyridine in the neocortex. J Neurosci. 2002;115:1067–78. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00533-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Traub RD, Bibbig RA, Piechotta A, Draguhn R, Schmitz D. Synaptic and nonsynaptic contributions to giant IPSPs and ectopic spikes induced by 4-aminopyridine in the hippocampus in vitro. J Neurophysiol. 2001;85:1246–56. doi: 10.1152/jn.2001.85.3.1246. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Traub RD, Cunningham MO, Whittington MA. Chemical synaptic and gap junctional interactions between principal neurons: Partners in epileptogenesis. Neural Netw. 2011;24:515–525. doi: 10.1016/j.neunet.2010.11.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Traub RD, Draguhn A, Whittington MA, Baldeweg T, Bibbig A, Buhl EH, et al. Axonal gap junctions between principal neurons: a novel source of network oscillations, and perhaps epileptogenesis. Rev Neurosci. 2002;13:1–30. doi: 10.1515/revneuro.2002.13.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Venance L, Rozov A, Blatow M, Burnashev N, Feldmeyer D, Monyer H. Connexin expression in electrical coupled postnatal rat brain neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:10260–10265. doi: 10.1073/pnas.160037097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Voss LJ, Jacobson G, Sleigh JW, Steyn-Ross A, Steyn-Ross M. Excitatory effects of gap junction blockers on cerebral cortex seizure-like activity in rats and mice. Epilepsia. 2009;50:1971–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1528-1167.2009.02087.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Voss LJ, Melin S, Jacobson G, Sleigh JW. GABAergic compensation in connexin36 knock-out mice evident during low-magnesium seizure-like event activity. Brain Res. 2010;1360:49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Voss LJ, Mutsaerts N, Sleigh JW. Connexin36 gap junction blockade is ineffective at reducing seizure-like event activity in neocortical mouse slices. Epilepsy Res Treatm. 2010;310753:1–6. doi: 10.1155/2010/310753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wang Y, Belousov AB. Deletion of neuronal gap junction protein connexin 36 impairs hippocampal LTP. Neurosci Lett. 2011;502:30–32. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2011.07.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wiebe S. Epidemiology of temporal lobe epilepsy. Can J Neurol Sci. 2000;27:S6–S21. doi: 10.1017/s0317167100000561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]