Abstract

Checklists have been used to improve quality in many industries, including healthcare. The use of checklists, however, has not been extensively evaluated in clinical ethics consultation. This article seeks to fill this gap by exploring the efficacy of using a checklist in ethics consultation, as tested by an empirical investigation of the use of the checklist at a large academic medical system (Cleveland Clinic). The specific aims of this project are as follows: (1) to improve the quality of ethics consultations by providing reminders to ethics consultants about process steps that are important for most patient-centered ethics consultations, (2) to create consistency in the ethics consultation process across the medical system, and (3) to establish an effective educational tool for trainers and trainees in clinical ethics consultation. The checklist was developed after a thorough literature review and an iterative process of revising and testing by a group of experienced ethics consultants. To pilot test the checklist, it was distributed to 46 ethics professionals. After a six-month pilot period in which ethics professionals used the checklist during their clinical activities, a survey was distributed to all of those who used the checklist. The 10-item survey examined consultants' perceptions regarding the three aims listed above. Of the 25 survey respondents, 11 self-reported as experts in ethics consultation, nine perceived themselves to have mid-level expertise, and five self-reported as novices. The majority (68 percent) of all respondents, regardless of expertise, believed that the checklist could be a “helpful” or “very helpful” tool in the consultation process generally. Novices were more likely than experts to believe that the checklist would be useful in conducting consultations. The limitations of this study include: reduced generalizability given that this project was conducted at one medical system, utilized a small sample size, and used self-reported quality outcome measures. Despite these limitations, to the authors' knowledge this is the first investigatation of the use of a checklist systematically to improve quality in ethics consultation. Importantly, our findings shed light on ways this checklist can be used to improve ethics consultation, including its use as an educational tool. The authors hope to test the checklist with consultants in other healthcare systems to explore its usefulness in different healthcare environments.

Introduction

The use of checklists in healthcare has recently gained momentum in the United States,1 and their use is positively correlated with a wide range of health and quality outcomes in the literature.2 Research most strongly supports the use of checklists in procedurally based clinical interventions,3 but studies have not assessed their use in clinical ethics. Checklists have gained the most prominence in surgical settings, where they were found to reduce or eliminate “never events,” such as operating on the incorrect patient.4 Studies report reductions in mortality,5 improved quality of care,6 and increased safety and communication with the implementation of checklists.7 Outside the surgical setting, checklists have been found to improve quality and consistency in sonograph8 and central venous catheterization skills.9 Most studies report that the use of checklists that were designed to standardize processes in healthcare improved the quality of care.10

The goal of ethics consultation is “to improve the quality of healthcare through the identification, analysis, and resolution of ethical questions or concerns.”11 Effectiveness in health services research is often defined as either procedure-based or outcome-based. In this article, we have focused on procedure-based outcomes. On initial review, ethics consultation may appear to defy a procedural approach because each ethics case is unique, with variation in ethical issues, interpersonal dynamics among stakeholders, and nuanced moral perspectives and analysis. These characteristics may limit the helpfulness of a “one size fits all” approach to ethics consultation because consultants must think objectively and independently and apply knowledge, skills, and experience to analyze and manage a case to ensure a “good ethics consultation outcome.” Nevertheless, there are multiple procedural steps that should be considered for most patient-focused ethics consultations. These standard actions can be categorized as information gathering, documentation, and follow up, and can appropriately be included in an ethics consultation checklist.

Quality outcomes in ethics consultation cannot be quantified as readily as a reduction in mortality or low infection rates in surgical procedures. In both fields, however, following procedural steps is necessary to improve quality in virtually every case. For instance, a surgical checklist probably inclues processes to identify the correct incision site and account for instruments before and after surgery. These steps do not guarantee a “good” outcome, yet they are critical components of providing high-quality care. Providing high-quality ethics consultation is equally process dependent, although critical actions often involve considering a circumstance or perspective rather than a concrete step like counting instruments. Checklists can help ensure that ethics consultants attend to key procedural steps.12 For example, the American Society of Bioethics and Humanities' Core Competencies for Healthcare Ethics Consultation states that the goals of ethics consultation are to “identify and analyze the nature of the value uncertainty or conflict…” and to “facilitate resolution of conflicts in a respectful atmosphere with attention to the interests, rights, and responsibilities of all those involved.”13 Consultants' efforts, then, to identify appropriate stakeholders, elicit their views, and consider how they might be assimilated with the views of other stakeholders are necessary steps. The use of a checklist that is designed to confirm these efforts (with entries such as: “Identified surrogate decision maker” “Other relevant stakeholders interviewed … physicians, nurses, social worker, chaplain”) increases the likelihood that ethics consultants will achieve the goals of ethics consultation. This checklist focuses on such process-oriented quality measures.

Checklists also offer the advantage of a standardized process. Clinical ethics consultation requires the ability to assess and assimilate sensitive information and potentially conflicting viewpoints in settings that often require in-the-moment judgment and response. While these skills and activities are not process steps, a checklist can promote consistent preparation that enables consultants to respond competently to the unexpected. Whether as a guide or a reminder, a checklist can offer reliable preparation to consultants when it accomplishes the following: encourages consultants' familiarity with stakeholders and medical and psychosocial facts, leads consultants through exploration of multiple viewpoints and barriers to consensus, and reminds consultants to communicate transparently and thoroughly throughout the consultation process. Finally, consistency in approach, particularly when it is substantiated by productive and appreciated results, engenders confidence in the ethics consultation service (ECS) within a healthcare system.

Methods

Background

The Cleveland Clinic established a Department of Bioethics in 1984. The main academic center campus of the Cleveland Clinic (hereafter, the “main campus”) currently has 1,400 hospital beds and handles nearly 140,000 outpatient visits per year. At the time of this pilot study, the department's 13 faculty bioethicists and four bioethics fellows represented diverse academic backgrounds including medicine, philosophy, health policy, law, theology, and education. The staff and fellows participate in the ECS. Because it has an “open access” ethics consultation policy, anyone with a legitimate interest in a patient's care (for example, physicians, nurses, social workers, chaplains, patients, family members) can request an ethics consultation.

As Cleveland Clinic expanded to include community hospitals, its ECS adapted to accommodate approaches within the various hospitals comprising the Cleveland Clinic Health System (CCHS). At the main campus, 11 of the Department of Bioethics' faculty members, supported by bioethics fellows, staff the ECS 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Each week, one faculty member is on service to respond to consultation requests. Bioethics fellows train by initially shadowing faculty members, then gain increasing independence as consultants during a two-year fellowship period. Ethics consultants at the main campus conduct more than 350 consultations annually, primarily using an individual consultant model. At the time of this study, the two other faculty in the Department of Bioethics, referred to as “regional ethicists,” served the eight community hospitals within CCHS. Each community hospital has its own multidisciplinary ethics committee whose members provide ethics consultation for their respective hospital. A regional ethicist supports each community hospital's ECS. There is variability among the eight hospitals as to whether an individual consultant or small team model is predominantly used. The community hospitals differ greatly in size, ranging from 100 beds to 500 beds. Consequently, the volume of ethics consultation varies among the community hospitals and is lower than the volume at the main campus. The range among the community hospitals is as little as eight consultations annually for a smaller hospital to more than 25 at some of the larger hospitals.

Study Design

The Checklist

The Clinical Ethics Advisory Committee (CEAC), comprised of five faculty members and one bioethics fellow in the Department of Bioethics, identifies and addresses opportunities for improvement in the ECS. The members of this group have substantial experience in ethics consultation as well as with programs to train consultants. The project to develop and study the use of a checklist arose in response to the efficacy of checklists in other areas of healthcare, and aimed to increase the likelihood that the ECS consultants across CCHS would undertake standardized process steps that are central to high-quality ethics consultations. CEAC members identified the following specific aims for the checklist project:

Improve the quality of ethics consultations by providing reminders to consultants about the process steps that are important in most patient-centered consultations,

Create consistency in the ethics consultation process across CCHS, and

Establish an educational tool for trainers and trainees in clinical ethics consultation.

CEAC members reviewed the literature regarding the use of checklists in healthcare broadly and in ethics consultation more specifically. Incorporating recommendations from the literature and from their own ethics consultation experience, CEAC members developed the checklist in an iterative fashion over a six-month period. Variation in the content of ethics consultations precluded an exhaustive list of critical inquiries and procedural steps for all consultations.

Brevity is an important attribute of a useful checklist. Lengthy checklists tend to be cumbersome and may not be used.14 Additionally, CCHS consultants record their activities in an electronic database with 31 fields of information captured by both free-text and drop-down boxes, so CEAC members sought to minimize consultants' experience of the checklist as additional record-keeping. Defining the type of checklist is also important.15 Based on the variation in the content of ethics consultation, the need to balance comprehensiveness of a checklist with utility, a desire to avoid duplicating database documentation efforts, and the need for brevity, CEAC members focused on a procedural checklist rather than on a substantive content-based checklist. They set a one-page limit for the checklist. CEAC members believed this would minimize burden on potential users and increase its rate of utilization.

The final version of the checklist (see table 1) encompasses possible activities for most consultations, including pragmatic tasks (for example: “Requester and contact information identified,” “Ethics note placed in EMR”) and analytical fundamentals (for example, “Reason for request identified,” “Appropriate referrals recommended”). The checklist also targets patient-centered considerations (for example: “Patient's decision-making capacity noted,” “Assessed patient's belief system that may affect care decisions”) as well as more generic considerations (for example: “Consulted/referenced relevant CCHS policies,” “Consulted relevant bioethics colleagues, clinical experts, literature”). Several items focus on information that is relevant to end-of-life issues (for example: “Does patient have advance directives,” “Resuscitation status noted”).

Table 1. The Cleveland Clinic Health System (CCHS) ethics consultation checklist.

| Item | Check if completed |

|---|---|

| Background information | |

| Requester and contact information identified | __________ |

| Confidentiality requested | __________ |

| Staff physician/attending identified and notified | __________ |

| Reason for request identified | __________ |

| EMR* reviewed for primary diagnosis, co-morbidities, reason for admission/clinic visit | __________ |

| Patient's social information gathered (e.g., spouse/significant other, children, other relevant family members, occupation, living situation, socio-economic status, religion, family dynamics, gender, age, financial concerns) | __________ |

| Assessment | |

| Patient's decision-making capacity noted | __________ |

| Does patient have advance directives (living will, HCPoA,** other) | __________ |

| Identified surrogate decision maker and documented name/contact information | __________ |

| Patient/family notified about ethics consult | __________ |

| If no, reasons documented | __________ |

| Interviewed patient/family | __________ |

| Other relevant stakeholders interviewed (e.g., physicians, nurses, social worker, chaplain) | __________ |

| Assessed patient's belief system that may affect care decisions | __________ |

| Resuscitation status noted | __________ |

| Portable DNR*** explored for patient with DNR being discharged | __________ |

| Consulted/referenced relevant CCHS policies | __________ |

| Consulted relevant bioethics colleagues, clinical experts, literature | __________ |

| Documentation and follow up | |

| Appropriate referrals recommended (e.g., chaplaincy, social work, palliative medicine, psychiatry) | __________ |

| Ethics note placed in EMR | __________ |

| If no, reason noted in bioethics database**** | __________ |

| Appropriate stakeholders updated about ethics involvement and recommendations | __________ |

| Information entered into bioethics database and reviewed for thoroughness | __________ |

EMR: electronic medical record

HCPoA: healthcare power of attorney

DNR: do not resuscitate

Database: refers to an ethics consultation database used by CCHS

The Cleveland Clinic Institutional Review Board (IRB) determined that this checklist pilot was a quality improvement project and therefore exempt from IRB oversight.

Distribution

The checklist was initially distributed via email to the individuals within CCHS who are responsible for ethics consultation: 13 faculty members in the Department of Bioethics, four bioethics fellows, and 29 members of community hospital ethics committees. An information sheet describing the purpose of the checklist, the development process, and the plan for the pilot study accompanied the checklist and encouraged consultants to use the checklist for 80 to 100 percent of all ethics consultations during the pilot period, 1 July through 31 December 2012. Faculty members at the main campus also received an email prior to their week on consultation service that included the checklist, the information sheet, and a reminder to use the checklist during consultations. Members of the community hospital ethics committees who were on call were reminded at monthly ethics committee meetings of their on-call status and to utilize the checklist when doing ethics consultations.

The Survey

Four months into the pilot, and again at the end of the six-month pilot, the CEAC distributed a link to an anonymous electronic online survey to all consultants, with a reminder email one month after the end of the pilot. At some of the community hospitals, paper copies of the survey were also distributed at ethics committee meetings.

The purpose of the survey was to examine whether consultants perceived that the checklist met its three objectives in an efficient and effective manner. The survey consisted of five open-ended and five closed-ended questions. Two of the close-ended questions solicited demographic information about the respondents' role in the ECS. Two Likert-type questions elicited feedback regarding consultants' perception of the checklist. The remaining close-ended question asked respondents to self-assess their level of expertise in consultation. Two open-ended questions asked respondents to report on how frequently they used the checklist, two solicited feedback on how to improve it, and one question asked for general feedback. See table 2 for a detailed list of the survey questions and answer options.

Table 2. The survey evaluating the self-reported quality of the checklist.

|

Statistical Analysis

Given the exploratory nature of the project and due to sample size restrictions, power calculations for hypothesis testing were not indicated. Rather, descriptive statistics (including means and standard deviations) were utilized to provide a summary of respondents' perceptions of the checklist and to provide pilot data for future investigations. An unpaired t test compared responses between respondents who did and respondents who did not give qualitative feedback in addition to their survey responses. Three questions concerning perceptions of how the checklist improved the quality of consultations were quantitatively similar, and were collapsed during analysis for ease of interpreting the data. Qualitative, open-ended responses were analyzed using thematic analysis to highlight both positive and negative reactions to using the checklist.

Results

Characteristics of the Respondents

Of the 46 ethics consultants invited to participate in the survey, 25 responded: 10 faculty members from the Department of Bioethics (40 percent of the sample), two bioethics fellows, and 13 members of community hospital ethics committees (52 percent). The overall response rate was 54.3 percent.

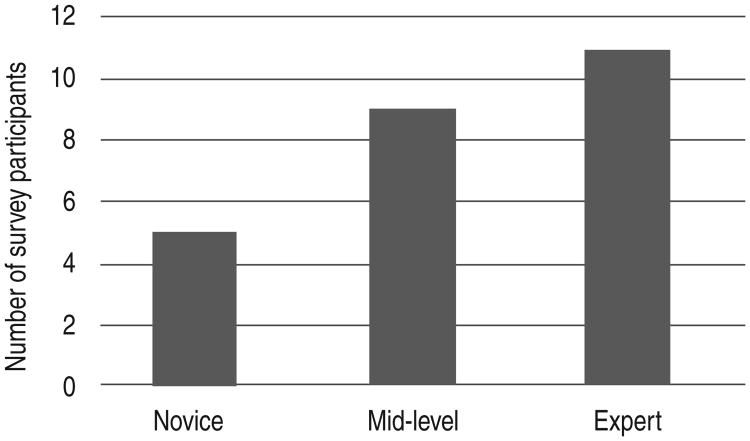

Of the 25 respondents, 11 classified themselves as experts in ethics consultation and five characterized themselves as novices; the remaining nine respondents characterized themselves as having midlevel expertise (see figure 1). In the Department of Bioethics, 91 percent of the faculty self-reported as experts and 9 percent (one respondent) self-reported as mid-level. The remaining respondents included consultants who are either trainees or healthcare professionals with primary duties in a discipline other than bioethics. These individuals would likely have spent significantly less time in ethics consultation.

Figure 1. Ethic consultants' self-reported expertise in using the checklist (n = 25).

Weighted averages were calculated using the open-ended questions on the use of the checklist. On average, respondents used the checklist approximately five times (range: zero to 20), and for approximately 62 percent of consultations (range: 0 percent to 100 percent) during the evaluation period.

All of the participants were responsible for conducting ethics consultations during the data collection phase, although some did not engage in any consultation during their time on service. Additionally, some participants may have been on service more frequently than others. Some ethics consultants (one member of the bioethics faculty and four members of community hospital ethics committees) participated in the survey despite never having used the checklist. Despite not using it during a consult, these individuals had the opportunity to read and reflect on the checklist.

Utility of the Checklist

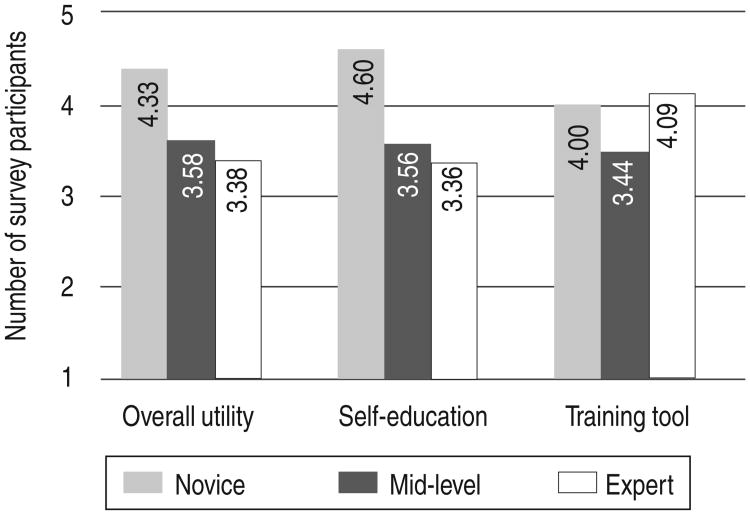

Overall the majority of all respondents, regardless of self-reported expertise, found the checklist to be useful in conducting ethics consultation: of the 25 respondents, 68 percent found it “helpful” or “very helpful” in conducting consultations generally; 12 percent found it “unhelpful” or “very unhelpful.” As a guide in the consultation process, 60 percent said it was “helpful” or “very helpful”; 16 percent indicated it was “unhelpful” or “very unhelpful.” As a reminder of appropriate actions during consultation, 64 percent found the checklist “helpful” or “very helpful”; nearly 17 percent indicated that the checklist was “unhelpful” or “very unhelpful” in this aspect. As a tool for self-education, 60 percent said it was “helpful” or “very helpful,” and nearly 63 percent found the checklist “helpful” or “very helpful” as a tool for teaching others about consultation (12.5 percent found it “unhelpful” or “very unhelpful”). As a tool for conducting consultations generally and as a tool for self-education, only 12 percent and 12.5 percent, respectively, found the checklist “unhelpful” or “very unhelpful.” Novices perceived the most benefit from using the checklist across all categories. Experts were most favorable about using the checklist as a training tool (see figure 2).

Figure 2. Perceived helpfulness of the checklist (n = 25).

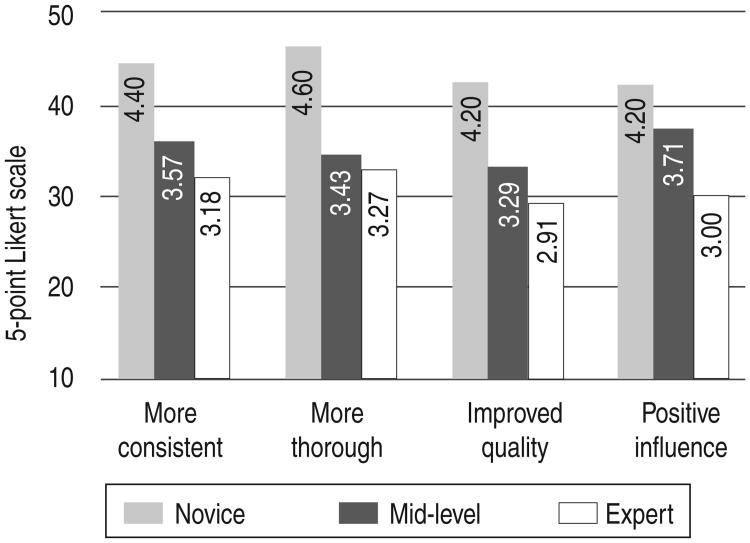

Perceived Effect of the Checklist on the Consultation Process

Novices indicated more frequently than experts the belief that the checklist would positively impact their future consultations. Novices indicated more frequently than mid-levels or experts the belief that the checklist would change how they conducted consultations, and would lead them to a more consistent approach in conducting ethics consultations, promote thoroughness and improve quality in their ethics consultations, or positively inform how they would conduct consultations in the future (see figure 3).

Figure 3. Level of concurrence with survey-related effects (n = 23).

Open-Ended Questions

Nine participants gave at least one substantive suggestion or comment. Four gave substantive suggestions for additions to the checklist. Two gave substantive suggestions for items that could be deleted. Six gave substantive comments at the end of the survey in addition to their survey responses. To compare the checklist favorability between participants who gave commentary and those who did not, an unpaired t test was conducted using respondents' overall impressions of the checklist. Responses to personal and training utility and impact on consultation process were collapsed into a single five-point Likert score, with a score of 1 as “least favorable” and a score of 5 as “most favorable.” Those who did not give comments and suggestions had an average response score of 3.81 (standard deviation = 0.81), while those who did provide feedback had an average response score of 3.22 (standard deviation = 0.94). The t test results indicated that the responses between those who did and those whoh did not give comments and suggestions were not statistically different (P value = 0.1095, 95 percent confidence interval = -0.144 to 1.33, t = 1.66). This result indicates a low likelihood of response bias in the open-ended questions, given that individuals who provided suggestions and those who did not rated the checklist similarly.

Responses to the open-ended questions in the survey yielded a variety of substantive comments and reactions, including the following (edited only for grammar):

“The checklist appears to be a valuable tool.”

“The checklist reminded me more to fill in the database fields rather than other aspects of doing the consultation.”

“Should not be implemented on main campus as a standard expectation. Creates redundancy in documentation with no substantive benefit to quality of advice.”

“… might add more space to actually write down important details about cases, in addition to merely checking-off items.”

“… needs to address the need for follow-up actions—it's written as if a consultation is a onetime activity.”

“Consider labeling it ‘Check if completed.’”

Discussion

Of the 25 respondents, 11 self-reported as experts, nine perceived themselves to be mid-level, and five as novices. The majority of all respondents, regardless of expertise, believed the checklist could be a useful tool in the consultation process. Novices, however, were more likely than experts to believe that the checklist would be useful in conducting consultations. Experts were most positive about the checklist as a tool for teaching others. Although they were able to recognize its utility, experts were less likely to believe that the checklist would alter how they would perform consultations in the future. Most novices (80 percent), however, answered “agree” or “strongly agree” when asked if the checklist would have an impact on how they would perform future consultations.

Checklists as Quality Improvement Tools

Checklists used for medical interventions16 seek to improve the quality of care by ensuring that specific procedural steps are taken to improve the safety of patients and to reduce medical error. While the outcomes of many medical interventions can be objectively measured,17 there is little consensus on how to objectively measure the success of an ethics consultation.18 Despite the lack of objective, quantitative measures, a significant literature examines quality improvement in ethics consultation.19 Our checklist aims to improve the quality of ethics consultation by identifying the procedural actions necessary for a “good” consultation20 and by encouraging their routine performance. It also seeks to obtain consistency in process throughout an ECS. This checklist serves as a reminder to collect key information, establish facts, and deliberate on critical considerations, regardless of the substantive questions raised by particular cases. Even if ethics consultants conclude that the yield from respective inquiries is low or not relevant to particular cases, omitting them entirely may impair the quality of the consultation process. We encourage future study of ethics consultation to focus on identifying and testing further the necessary procedural components of high-quality ethics consultation.

These process-oriented steps are essential.21 Without the information collected by the checklist, a consultant cannot have a complete picture of the patient or the circumstances influencing ethics questions and analysis. One example would be a failure by a consultant to ascertain the existence of an advance directive, which could result in a violation of the patient's autonomy. In other words, the checklist might be necessary but not sufficient to ensure high-quality ethics consultation. There is much room for nuanced analysis beyond the process steps identified by the checklist, but without the information it is designed to remind an ethics consultant to collect, an ethics consultation is deficient.

Beyond its use as a reminder to take certain procedural steps, the checklist serves as a tool for communication, particularly for trainees and other professionals involved in consultation, such as attending physicians and social work and nursing supervisors who teach trainees. The checklist can be used as a point of inquiry for a trainee who does not understand why some data on the patient are needed in an ethics consultation or how the data should be incorporated into an ethical analysis.

The survey results indicate that consultants perceived the checklist as a helpful tool. Both novice and expert ethicists perceived the checklist to be helpful as a reminder of appropriate actions during consultation and in guiding the consultation process. While the checklist might have served as a useful reminder for all respondents, regardless of level of expertise, those reporting less experience in ethics consultation perceived the checklist as more beneficial than those claiming more experience.

Consultants with greater expertise may have already established routines that support a high-quality consultation process, and may perceive their approach to be virtually reflexive or intuitive. Although the intuitions of experts are often highly valuable, relying on intuition may place an expert at risk of overlooking facts that may be inconsistent with their experience and expertise. The checklist may serve as an opportunity to convert quick thinking into careful deliberation. Some experts' discounting of the checklist's value might also reflect the assumption that “you don't know what you don't know,” which can result in an overconfidence in one's skills, and may be a barrier to learning.22 Studies assessing checklists in other healthcare domains report that while checklists tend to be met with the most resistance by those most experienced in their respective field, these individuals tend to show the most benefit from the use of a checklist.23

Limitations

This study has several limitations. While there is little consensus on objective measures for successful outcomes in ethics consultation, the checklist prompts consultants to gather key components of the ethics consultation process.24 The small sample size reduces the external validity and the generalizability of the results. Despite the small size of the sample, however, it includes professionals with a wide variety of backgrounds, years of experience, and practice settings (that is, academic medical center and community hospitals). Additional limitations stem from practical concerns that frequently plague research to improve clinical practices. For example, some consultants at the community hospitals did not have an opportunity to use the checklist during the pilot study because they did not engage in ethics consultation during the time period. As with many pilot studies, practical barriers arose that were out of investigators' control. Consultants at four of the community hospitals received the checklist later than the planned initial distribution; they received the checklist two months into the pilot period, and their regional ethicist was on a leave of absence for most of the pilot, so they did not receive guidance on its use. This may have affected the rate of use, response rates, and responses in these areas.

Additionally, the results of this pilot reflect the perceptions of ethics consultants in one healthcare system. This limitation is mitigated by the fact that CCHS hospitals use different models of ethics consultation (that is, an individual consultant versus a small team whose members are not primarily employed as ethicists). Multiple hospitals and consultation models enabled the inclusion of ethics consultants with a wide range of expertise and approaches to consultation.

Selection bias is another potential limitation, specifically with respect to satisfaction with or usefulness of the tool. That is, those respondents who most liked the checklist may be more likely to participate in the survey to provide feedback. Yet the response rate was high from the main campus, where there was significant variation in the level of support for the checklist; this may alleviate the selection bias limitation to some degree.

Conclusions

As stated earlier, specific aims for the checklist were to: (1) improve the quality of ethics consultations by providing reminders to consultants about process steps important for most patient-centered consultations, (2) create consistency in the ethics consultation process across CCHS, and (3) establish an educational tool for trainers and trainees in clinical ethics consultation. This checklist does not attempt to address the nuances of substantive content, emotion, and interpersonal dynamics that are consistently present in ethics consultation, nor does it direct the moral analyses required for quality ethics consultation. Overall, respondents thought that the checklist improved quality, increased consistency, and served as an educational tool.

The commonly applied structure for quality improvement initiatives is a plan, do, study (or check), act cycle, also referred to as the Deming Cycle.25 As discussed above, the CEAC completed the first three steps of this cycle through the development of the checklist, the pilot, and the survey. The final step will be to incorporate the feedback received by making necessary revisions to the checklist and put it into use. Optimally, testing at other institutions would provide additional feedback for further enhancement of the tool.

Contributor Information

Lauren Sydney Flicker, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Montefiore Medical Center, in New York.

Susannah L. Rose, Email: roses2@ccf.org, the Cleveland Clinic Department of Bioethics and ---- at Case Western Reserve University.

Margot M. Eves, Humanities and Spiritual Care at the Cleveland Clinic.

Anne Lederman Flamm, Email: flamma@ccf.org, Cleveland, Ohio.

Ruchi Sanghani, the Cleveland Clinic Department of Bioethics.

Martin L. Smith, Humanities and Spiritual Care at Cleveland Clinic.

Notes

- 1.Arriaga AF, et al. Simulation-based trial of surgical-crisis checklists. New England Journal of Medicine. 2013 Jan;368(3):246–53. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa1204720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Bump GM, Bost JE, Buranosky R, Elnicki M. Faculty member review and feedback using a sign-out checklist: Improving intern written sign-out. Academic Medicine. 2012 Aug;87(8):1125–31. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31825d1215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gawande A. The Checklist Manifesto: How to Get Things Right. New York: Metropolitan Books; 2009. pp. 32–47. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arriaga et al., “Simulation-based trial,” see note 1 above; Bump et al., “Faculty member review,” see note 1 above; Bahner DP, et al. A Novel Model of Teaching and Performing Focused Sonography. Journal of Ultrasound Medicine. 2012 Feb;31:295–300. doi: 10.7863/jum.2012.31.2.295.Ma IWY, et al. Comparing the use of global rating scale with checklists for the assessment of central venous catheterization skills using simulation. Advances in Health Science Education. 2012 Oct;17:457–70. doi: 10.1007/s10459-011-9322-3.Haynes AB, et al. A surgical safety checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. New England Journal of Medicine. 2009 Jan;360(5):491–9. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0810119.Neily J, et al. Association between implementation of a medical team training program and surgical mortality. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2010 Oct;304:1693–700. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1506.

- 4.Haynes et al., “A surgical safety checklist,” see note 3 above; Neily et al., “Association between implantation,” see note 3 above; Birkmeyer JD, Miller DC. Can checklists improve surgical outcomes? Nature Reviews Urology. 2009 May;6(5):245–6. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2009.57.Birkmeyer JD. Strategies for improving surgical quality—checklists and beyond. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010 Nov;363(20):1963–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJMe1009542.de Vries EN, et al. Effect of a comprehensive surgical safety system on patient outcomes. New England Journal of Medicine. 2010 Nov;363(20):1928–37. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0911535.

- 5.Haynes et al., “A surgical safety checklist,” see note 3 above; Neily et al., “Association between implantation,” see note 3 above.

- 6.Arriaga et al., “Simulation-based trial,” see note 1 above; Birkmeyer, “Strategies for improving surgical quality,” see note 4 above.

- 7.Walker IA, Reshamwalla S, Wilson IH. Surgical safety checklists: Do they improve outcomes? British Journal of Anaesthesia. 2012 May;:1–8. doi: 10.1093/bja/aes175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bahner et al., “A Novel Model of Teaching,” see note 3 above.

- 9.Ma, “Comparing the use of global rating scale,” see note 3 above.

- 10.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) Patient safety in obstetrics and gynecology: ACOG Committee Opinion No. 447. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2009 Dec;114:1424–7. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181c6f90e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ACOG. Patient Safety Checklist No. 1: Scheduling induction of labor. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2011 Dec;118:1203–4. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318240d429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ACOG. Patient Safety Checklist No. 2: Inpatient induction of labor. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2011 Dec;118:1205–6. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318240d429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ACOG. Patient Safety Checklist No. 3:Scheduling planned cesarean delivery. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2011 Dec;118:1469–70. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31823ed20d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ACOG. Patient Safety Checklist No. 4: Preoperative planned cesarean delivery. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2011 Dec;118:1471–2. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31823ed223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ACOG. Patient Safety Checklist No. 5: Scheduling induction of labor. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2011 Dec;118:1473–4. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318240d429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ACOG. Patient Safety Checklist No. 6: Documenting Shoulder Dystocia. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2012 Aug;120:430–1. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318268053c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ACOG. Patient Safety Checklist No. 7: Magnesium sulfate before anticipated birth for neuroprotection. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2012 Aug;120:432–3. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e318268054c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ACOG. Patient Safety Checklist No. 8: Appropriateness of trial of labor after previous cesarean delivery (antepartum period) Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2012 Aug;120:1254–5. doi: 10.1097/01.aog.0000422588.22542.e0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ACOG. Patient Safety Checklist No. 9: Trial of labor after previous cesarean delivery (interpartum admission) Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2012 Aug;120:1256–7. doi: 10.1097/01.aog.0000422539.04754.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; ACOG. Patient Safety Checklist No. 10: Postpartum hemorrhage after vaginal delivery. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2013 May;121:1151–2. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Core Competencies for Health Care Ethics Consultation. 2nd. Glenview, Ill.: American Society of Bioethics and Humanities; 2011. p. 3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sokol DL. Rethinking Ward Rounds. BMJ. 2009;338:571. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Core Competencies, see note 11 above.

- 14.Ontario Hospital Association, Part B: Surgical Safety Checklist. How-To Implementation Guide. 2010:30. http://www.oha.com/CurrentIssues/keyinitiatives/PatientSafety/Documents/SSC_Toolkit_PartB_Feb04.pdf.

- 15.Ibid., 29-47

- 16.Arriaga et al., “Simulation-based trial,” see note 1 above; ACOG patient checklists, see note 10 above.

- 17.Arriaga et al., “Simulation-based trial,” see note 1 above.

- 18.Core Competencies, see note 11 above; Agich GJ. Why quality is addressed so rarely in clinical ethics consultation. Cambridge Quarterly of Healthcare Ethics. 2009 Fall;18(4):339–46. doi: 10.1017/S0963180109090549.

- 19.Agich, “Why quality is addressed so rarely,” see note 18 above; Opel DJ, et al. Integrating Ethics and Patient Safety: The Role of Clinical Ethics Consultants in Quality Improvement. The Journal of Clinical Ethics. 2009 Winter;20(4):220–7.Singer P, et al. Revisiting Clinical Ethics. BMC Medical Ethics. 2001 Apr;2:1. doi: 10.1186/1472-6939-2-1.

- 20.Core Competencies, see note 11 above.

- 21.Ibid.

- 22.Con Roenn J, von Gunten C. The Care People Need and the Education of Physicians. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2011 Dec;29(36):4742–3. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.39.2043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fourcade A, et al. Barriers to staff adoption of a surgical safety checklist. BMJ Quality and Safety. 2012;21:191–7. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2011-000094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Nørgard K, Ringstead C, Dolmans D. Validation of a checklist to assess ward round performance in internal medicine. Medical Education. 2004 Jul;38(7):700–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2004.01840.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Core Competencies, see note 11 above; ASBH. [accessed 19 September 2014];Code of Ethics and Professionalism Responsibilities for Healthcare Ethics Consultants. http://www.asbh.org/uploads/files/pubs/pdfs/asbh_code_of_ethics.pdf.

- 25.Best M, Neuhauser D. Walter A. Shewhart, 1924, and the Hawthorne factory. Quality & Safety Health Care. 2006;15:142–3. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2006.018093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Taylor M, et al. Systematic review of the application of the plan-do-study-act method to improve quality in healthcare. BMJ Quality & Safety. 2013:1–9. doi: 10.1136/bmjqs-2013-001862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]