Abstract

Background

Pressure at the interface between bony prominences and support surfaces, sufficient to occlude or reduce blood flow, is thought to cause pressure ulcers (PrUs). Pressure ulcers are prevented by providing support surfaces that redistribute pressure and by turning residents to reduce length of exposure.

Objective

We aim to determine optimal frequency of repositioning in long-term care (LTC) facilities of residents at risk for PrUs who are cared for on high-density foam mattresses.

Methods

We recruited residents from 20 United States and 7 Canadian LTC facilities. Participants were randomly allocated to 1 of 3 turning schedules (2-, 3-, or 4-hour intervals). The study continued for 3 weeks with weekly risk and skin assessment completed by assessors blinded to group allocation. The primary outcome measure was PrU on the coccyx or sacrum, greater trochanter, or heels.

Results

Participants were mostly female (731/942, 77.6%) and white (758/942, 80.5%), and had a mean age of 85.1 (standard deviation [SD] ± 7.66) years. The most common comorbidities were cardiovascular disease (713/942, 75.7%) and dementia (672/942, 71.3%). Nineteen of 942 (2.02%) participants developed one superficial Stage 1 (n = 1) or Stage 2 (n = 19) ulcer; no full-thickness ulcers developed. Overall, there was no significant difference in PrU incidence (P = 0.68) between groups (2-hour, 8/321 [2.49%] ulcers/group; 3-hour, 2/326 [0.61%]; 4-hour, 9/295 [3.05%]. Pressure ulcers among high-risk (6/325, 1.85%) versus moderate-risk (13/617, 2.11%) participants were not significantly different (P = 0.79), nor was there a difference between moderate-risk (P = 0.68) or high-risk allocation groups (P = 0.90).

Conclusions

Results support turning moderate- and high-risk residents at intervals of 2, 3, or 4 hours when they are cared for on high-density foam replacement mattresses. Turning at 3-hour and at 4-hour intervals is no worse than the current practice of turning every 2 hours. Less frequent turning might increase sleep, improve quality of life, reduce staff injury, and save time for such other activities as feeding, walking, and toileting.

Plain Language Summary

Bedsores are caused by pressure where bones under the skin meet support surfaces (like mattresses). Pressure reduces blood flow. Bedsores cause problems for many older patients. Bedsores increase the rate of patients’ death by as much as 400%, increase hospitalization, and decrease quality of life. Treating bedsores is costly.

One way to prevent bedsores among long-term care (LTC) residents is to turn patients throughout the day to reduce pressure in areas likely to develop ulcers. High-density foam mattresses can reduce how often residents must be turned. Currently Ontario LTC facilities turn patients every 2 hours.

This study aimed to determine the best interval to use in turning LTC residents (cared for on high-density foam mattresses) who are at risk for bedsores. We examined the benefits and costs of turning patients every 2, 3, and 4 hours in a randomized controlled trial that recruited residents from 20 United States and 7 Canadian LTC homes. Residents had no bedsores at the beginning of the study, were 65 years or older, and had moderate (scores 13–14) or high (scores 10–12) risk for bedsores. Participants continued their usual daily activities. The study continued for 3 weeks while study coordinators who did not know which group patients were in assessed patients’ risk and skin every week.

Overall, results of the study support turning moderate- and high-risk residents at intervals of 2, 3, or 4 hours when they are cared for on high-density foam mattresses. Turning at 3- and 4-hour intervals is no worse than turning every 2 hours. Less frequent turning could be better for LTC residents because it can increase sleep, improve quality of life, reduce staff injury, and save time for such other activities as feeding, walking, and using the toilet.

Background

The most basic strategy recommended by physicians and nurses to prevent pressure ulcers (PrUs) is the practice of turning or repositioning residents at 2-hour intervals. Turning every 2 hours, 12 times daily, 365 days annually, results in 4,380 turning episodes per patient yearly. Estimating 5 minutes per turn, 21,900 minutes, 365 hours, or 9.125 weeks of staff time per resident is required annually. Turning often requires 2 staff members, doubling the cost of the intervention.

Pressure at the interface between bony prominences and support surfaces, sufficient to occlude or reduce blood flow, is thought to cause PrUs. (1, 2) By providing support surfaces that redistribute pressure and by turning residents to reduce length of exposure, some PrUs can be prevented. High-density foam mattresses distribute pressure more evenly and are replacing springform mattresses used almost exclusively before the 2000s. A recent study by Li et al (3) found a steady decrease in PrUs in 2-year increments from 2002 to 2008. The authors speculated that increased use of high-density foam mattresses likely reduced exposure to pressure, providing a margin of error so that, even when turning didn't occur as recommended, pressure-relief properties of the mattresses protected residents from excessive pressure. (4)

Turning residents every 2 hours, recommended in many guidelines to reduce exposure to pressure, is not practised uniformly. Bates-Jensen and colleagues demonstrated through hourly observation and thigh sensors that residents are in practice turned less frequently than every 2 hours. (5) Turning is not benign. It decreases quality of life for residents because of repeated awakenings at night. Staff risk injury and the facility risks loss of its workforce. Determining the appropriate frequency of turning when high-density foam mattresses are used is important to keep residents safe, to improve quality of life (e.g., increase in ambulation, feeding assistance, toileting), and to make judicious use of staff time.

This clinical trial aimed to determine the optimal frequency of turning long-term care (LTC) facility residents with mobility limitations who were cared for on high-density foam mattresses for the purpose of preventing PrUs. Participants stratified by 2 levels of risk according to the Braden Scale for Predicting Pressure Sore Risk (hereafter Braden Scale) were compared as follows: (a) moderate-risk (Braden Scale score 13–14) participants randomly assigned to turning at every 2 compared with every 3 or 4 hours; or (b) high-risk (Braden Scale score 10–12) participants randomly assigned to turning every 2 compared with every 3 or 4 hours. (6, 7)

Research Methods

Design and Participants

This multicentre clinical trial had 2 levels of stratification, random allocation to 1 of 3 turning frequencies, and masked assessment of the outcome. Participants were randomly allocated via numbered envelopes in blocks of 6 according to risk-stratification group (moderate versus high) to 1 of 3 repositioning schedules (2-, 3-, or 4-hour intervals) when in bed. The study continued for 3 weeks after randomization with weekly risk and skin assessment completed by assessors blinded to treatment group.

The outcome, PrUs on the coccyx or sacrum, trochanter, or heel (sites most susceptible to pressure while people lie in bed), was determined by weekly blinded assessment. Residents were stratified by risk level because lower risk hypothetically is associated with fewer PrUs. The protocol continued for 3 weeks, because 90% of PrUs developed in the first 3 weeks after facility admission in a previous study. (8)

Data were collected from LTC facilities in the United States (n = 20) and in Ontario, Canada (n = 7). The LTC facilities in the United States were identified through quality-improvement organizations, corporate nurses of proprietary chains, the Advancing Excellence Campaign, and other contacts. Canadian LTC facilities identified by The Toronto Health Economics and Technology Assessment (THETA) Collaborative had to be situated in the greater Toronto area and be willing to participate in research.

Criteria for including LTC facilities were stable leadership, high-density foam mattresses on participants’ beds, overall quality according to Nursing Home Compare in the United States, and the ability to respond promptly to investigators. High-density foam mattresses of various brands and models were included because no product has demonstrated superiority. In the United States, quality of the LTC facilities was reported to be 4- or 5-star according to Nursing Home Compare with low (below 5%) incidence of PrUs to ensure above-average preventive care where outcomes could be related to turning rather than to less effective care. (9) Participants in Canadian facilities were provided with new high-density foam mattresses because of variation in the types and ages of existing mattresses.

Ethics Committees at the University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, University of Toronto, and one clinical site approved the protocol. Each LTC facility in the United States completed Federal Wide Assurance indicating acceptance of this ethics review before on-site training.

Participants were 65 years of age or older, free of PrUs when the study began, at moderate (Braden Scale score 13–14) or high (Braden Scale score 10–12) risk for PrUs, had mobility limitations (≤3 on Braden mobility subscale), and were on high-density foam mattresses. Participants were newly admitted short-stay residents (in facility for ≤7 days) or long-stay residents (in LTC facility for ≥90 days). These resident groups are different in that short-stay residents have had recent illness or surgery or a physiologic or cognitive transition that could be associated with stress (perhaps predisposing to PrUs); long-stay residents would likely be more physiologically stable but more challenged by needs for assistance with activities of daily living.

Residents were excluded on the basis of length of stay; of Braden Scale mobility scores indicating independent mobility (4); or of Braden Scale scores indicating very high risk (6–9), low risk (15–18), or not at risk (19–23). Residents at no risk or low risk do not lie in one position for 2 hours, are in and out of bed, and (as pilot work indicates) do not comply with a turning regimen. Residents at very high risk (scores ≤9) are often cared for on a powered mattress or alternating pressure-relief overlays.

On-site LTC Facility Training

On-site training by the study team was completed at each LTC facility in 2 to 3 days. A study coordinator, recruiter(s), assessor(s), and record managers received individual training, and inter-rater reliability was determined for assessors during training and at quarterly intervals. Licensed nurse supervisors were trained to observe and document position, record adverse events, and document skin care orders should a PrU develop. Certified nursing assistants (CNAs) in the United States and personal support workers (PSWs) in Canada were trained to carry out the intervention: to turn and check briefs according to assigned schedule and to document position change, heel elevation, skin condition, briefs status, and incontinence care at each repositioning. These CNAs and PSWs were trained in shift hand-off so that oncoming shifts could identify study participants. Following training, a mock trial was conducted. The LTC facilities participated until all eligible, consenting residents were studied.

Residents were screened and asked for consent by the recruiter. Consent was obtained from residents judged competent to sign on the basis of satisfactory answers to 3 questions related to the protocol after the study was explained; alternatively, consent from a legal representative was obtained.

Participants were allocated to study groups when consent was obtained. Two sets of numbered envelopes were used, one each for high and moderate risk. Each envelope contained another envelope with the turning frequency. Because sites varied in size, turning frequency was randomized in blocks of 6 to ensure equal distribution of turning at each site. The recruiter placed study materials and documentation in participant rooms and notified staff of start time. Given staff constraints, units studied up to 3 subjects at one time; as one subject completed, another began.

Staff were expected to turn patients within 30 minutes of the scheduled time and to record each turn. The study focused on turning in bed and documented time patients spent in a chair. Skin over bony prominences was inspected, and the condition of the skin was documented. Supervisors were notified of changes in skin condition.

Facility-wide PrU prevention measures in LTCs, such as use of chair cushions, heel-protector boots, or heel elevation, were continued throughout the study. Participants would sit in chairs, go to meals, bathe, and go to therapy as usual. Practices were generally consistent with guidelines for prevention of PrUs, and effectiveness was judged by relatively low incidence of new PrUs reported by each LTC facility. (10, 11)

Supervisors observed and recorded participants’ positions hourly. Supervisor-observed positions, compared with CNA- and PSW-reported turns, were one measure of treatment fidelity. Adverse events were reported, study forms checked for completeness, documentation faxed to Texas, and forms mailed to the project office (at the University of Toronto) for data verification and storage.

Treatment fidelity was assessed in 3 ways:

Documentation from CNAs and PSWs was evaluated monthly for percent on-time turning (reported turns occurring within 30 minutes of assigned turning time/total expected turns);

Documentation from CNAs and PSWs of mean length of time patients spent in one position;

Percent agreement between participant position and length of time in position as documented on CNA or PSW repositioning forms and supervisor-reported hourly position status.

Project staff sent printed reports to study sites for monthly quality-assessment teleconferences with a goal of 80% on-time turning and 80% of position changes in agreement. If agreement was below 80%, improvement was discussed.

Inter-rater reliability between the trainer and nurse assessors was examined during training sessions (R = 0.926) and evaluated quarterly (r = 0.897) to prevent drift in measurement of the Braden Scale.

Statistical Analysis

Stage 1 PrUs were identified if they were present at 2 separate observations. Descriptive statistics were used: frequencies for categorical participant, intervention, and outcome measures, and mean and standard deviation (SD) for continuous measures. Bivariate analyses were used to test the relationships between each risk group and within risk group by allocation to groups in which patients were turned every 2, 3, or 4 hours. For discrete variables, contingency tables were created and Wilcoxon tests (for ordered categories) were performed with Fisher's exact tests for 2 × 2 tables. For continuous variables, 2-sample t tests or analysis of variance were used. Logistic regression analyses were used to predict likelihood of PrU development. A 2-sided P value <0.05 was considered statistically significant. Analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

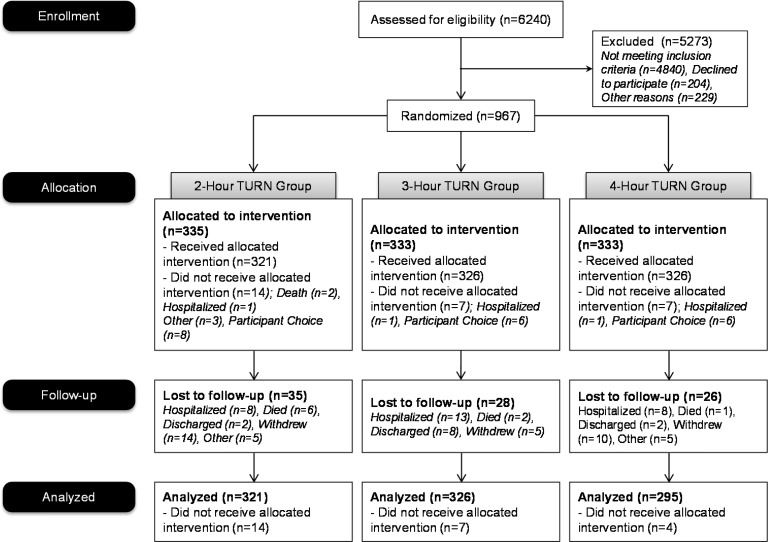

Among 6,240 residents screened, 1,400 met eligibility requirements; 967 agreed to participate (Figure 1). Moderate- and high-risk participants were allocated to turning every 2 (335 patients), 3 (333 patients), or 4 hours (299 patients). However, 25 residents who were allocated to a study group, but did not receive the intervention because of death, hospitalization by choice, or for other reasons that surfaced before the beginning of the study period, are not included in the final analysis, resulting in 942 participants (321 turned every 2 hours, 326 turned every 3 hours, and 295 turned every 4 hours).

Figure 1: Patient Flow Diagram.

Participants were predominantly female (731/942, 77.6%) and white (758/942, 80.5%), with a mean age of 85.1 (SD ± 7.66) years. The most common comorbidities were cardiovascular disease (713/942, 75.7%) and dementia (672/942, 71.3%) (Table 1). There was no significant difference in age between moderate- and high-risk groups; however, high-risk participants included more women (267/325, 82.2%) versus moderate-risk participants (464/617, 75.2%) and had a higher prevalence of dementia (251/325, 77.2%) than moderate-risk participants (421/617, 68.2%). High-risk participants had significantly lower body mass index (BMI), Braden Scale total, and Braden Scale subscale scores; lower percentage of meals eaten; and higher percentage of wet briefs observed (P ≤ 0.004) than moderate-risk patients.

Table 1:

Demographic and Risk Status Characteristics for All Participants—Differences between Moderate- and High-Risk Participants (United States and Canadian Data Combined)

| Variable | Patients (N = 942) | Mean (SD) or % | Moderate Risk (n = 617) | Mean (SD) or % | High Risk (n = 325) | Mean (SD) or % | Difference (High vs. Moderate) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 939 | 85.07 (7.66) | 615 | 85.24 (7.65) | 324 | 84.75 (7.69) | 0.357a |

| BMI (measured as kg/m2) | 905 | 25.11 (6.04) | 598 | 25.69 (5.95) | 307 | 23.99 (6.06) | <0.001a |

| Braden Total Score | 931 | 12.84 (1.17) | 613 | 13.57 (0.50) | 318 | 11.44 (0.73) | <0.001a |

| Sensory perception | 931 | 2.65 (0.65) | 613 | 2.88 (0.58) | 318 | 2.21 (0.55) | <0.001a |

| Moisture | 931 | 2.02 (0.66) | 613 | 2.16 (0.63) | 318 | 1.76 (0.64) | <0.001a |

| Activity | 931 | 2.02 (0.31) | 613 | 2.07 (0.33) | 318 | 1.94 (0.25) | <0.001a |

| Mobility | 931 | 2.06 (0.51)613 | 2.21 (0.46) | 613 | 318 | 1.77 (0.48) | <0.001a |

| Nutrition | 931 | 2.68 (0.65) | 613 | 2.75 (0.61) | 318 | 2.54 (0.72) | <0.001a |

| Friction | 931 | 1.40 (0.49) | 613 | 1.50 (0.50) | 318 | 1.21 (0.41) | <0.001a |

| Mean percentage of meals eaten over study | 941 | 75.06 (21.63) | 616 | 76.53 (20.94) | 325 | 72.29 (22.66) | 0.004a |

| All data severity | 927 | 25.25 (21.31) | 610 | 24.70 (19.83) | 317 | 26.30 (23.92) | 0.310a |

| Wet times/day | 942 | 4.17 (1.59) | 617 | 4.04 (1.58) | 325 | 4.43 (1.57) | <0.001a |

| Women | 731 | 77.60 | 464 | 75.20 | 267 | 82.15 | 0.017 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| White | 758 | 80.47 | 506 | 82.01 | 252 | 77.54 | 0.056 |

| Black | 55 | 5.84 | 37 | 6.00 | 18 | 5.54 | |

| Asian | 101 | 10.72 | 59 | 9.56 | 42 | 12.92 | |

| Hispanic | 22 | 2.34 | 14 | 2.27 | 8 | 2.46 | |

| Other | 6 | 0.64 | 1 | 0.16 | 5 | 1.54 | |

| Diagnosis category | |||||||

| Dementia | 672 | 71.34 | 421 | 69.02 | 251 | 79.18 | |

| Cerebrovascular | 341 | 36.20 | 216 | 35.41 | 125 | 39.43 | |

| Diabetes | 252 | 26.75 | 173 | 28.36 | 79 | 24.92 | |

| Cardiovascular | 713 | 75.69 | 491 | 80.49 | 222 | 70.03 | |

| Musculoskeletal | 506 | 53.72 | 333 | 54.59 | 173 | 54.57 | |

| Thyroid disorder | 167 | 17.73 | 111 | 18.20 | 56 | 17.67 | |

| Nutritional | 18 | 1.91 | 5 | 0.82 | 13 | 4.10 | |

| Admission eligibility | |||||||

| Long stay | 814 | 86.41 | 527 | 85.41 | 287 | 88.31 | 0.231 |

| Short stay | 128 | 13.59 | 90 | 14.59 | 38 | 11.69 | |

| Country | |||||||

| Canada | 505 | 53.61 | 336 | 54.46 | 169 | 52.00 | 0.492 |

| United States | 437 | 46.39 | 281 | 45.54 | 156 | 48.00 | |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation.

t test performed.

Table 2:

Demographic and Risk Status Characteristics for All Participants—Differences Between Moderate- and High-Risk Participants (Ontario Data Only)

| Variable | Patients | Mean (SD) or % | Moderate Risk | Mean (SD) or % | High Risk | Mean (SD) or % | Difference (High vs. Moderate) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 505 | 85.90 (7.38) | 336 | 86.06 (7.26) | 169 | 85.59 (7.61) | 0.496a |

| BMI (measured as kg/m2) | 501 | 24.28 (5.47) | 335 | 25.08 (5.62) | 166 | 22.68 (4.80) | <0.001a |

| Braden Total Score | 504 | 12.89 (1.16) | 336 | 13.60 (0.49) | 168 | 11.48 (0.74) | <0.001a |

| Sensory perception | 504 | 2.69 (0.69) | 336 | 2.94 (0.59) | 168 | 2.19 (0.59) | <0.001a |

| Moisture | 504 | 2.04 (0.56) | 336 | 2.11 (0.55) | 168 | 1.90 (0.56) | <0.001a |

| Activity | 504 | 2.04 (0.25) | 336 | 2.07 (0.28) | 1.68 | 1.98 (0.15) | <0.001a |

| Mobility | 504 | 2.03 (0.52) | 336 | 2.21 (0.45) | 168 | 1.68 (0.49) | <0.001a |

| Nutrition | 504 | 2.76 (0.62) | 336 | 2.84 (0.56) | 168 | 2.58 (0.70) | <0.001a |

| Friction | 504 | 1.34 (0.47) | 336 | 1.43 (0.50) | 168 | 1.14 (0.35) | <0.001a |

| Mean percentage of meals eaten over study | 505 | 81.52 (18.25) | 336 | 83.67 (16.09) | 169 | 77.24 (21.33) | <0.001a |

| All data severity | 504 | 21.52 (16.18) | 336 | 21.85 (15.23) | 168 | 20.86 (17.95) | 0.537a |

| Wet times/day | 505 | 4.02 (1.09) | 336 | 3.95 (1.14) | 169 | 4.14 (0.97) | 0.049a |

| Women | 384 | 76.04 | 244 | 72.62 | 140 | 82.84 | 0.011 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||

| White | 379 | 75.05 | 262 | 77.98 | 117 | 69.23 | 0.053 |

| Black | 21 | 4.16 | 12 | 3.57 | 9 | 5.33 | |

| Asian | 97 | 19.21 | 57 | 16.96 | 40 | 23.67 | |

| Hispanic | 6 | 1.19 | 5 | 1.49 | 1 | 0.59 | |

| Other | 2 | 0.40 | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 1.18 | |

| Diagnosis category | |||||||

| Dementia | 361 | 71.63 | 223 | 66.37 | 138 | 82.14 | |

| Cerebrovascular | 209 | 41.47 | 136 | 40.48 | 73 | 43.45 | |

| Diabetes | 121 | 24.01 | 86 | 25.60 | 35 | 20.83 | |

| Cardiovascular | 348 | 69.05 | 244 | 72.62 | 104 | 61.90 | |

| Musculoskeletal | 285 | 56.55 | 188 | 55.95 | 97 | 57.74 | |

| Thyroid disorder | 75 | 14.88 | 49 | 14.58 | 26 | 15.48 | |

| Nutritional | 2 | 0.40 | 0 | 0.00 | 2 | 1.19 | |

| Admission eligibility | |||||||

| Long stay | 473 | 93.66 | 312 | 92.86 | 161 | 95.27 | 0.338 |

| Short stay | 32 | 6.34 | 24 | 7.14 | 8 | 4.73 | |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation.

t test performed

More moderate- (n = 617) than high-risk (n = 325) residents participated. Fewer high-risk participants were allocated to 4- (n = 97) versus 2- (n = 111) and 3-hour turning (n = 117), because allocation of 4-hour turning of high-risk participants was delayed in the United States. There were no significant differences between turning groups for moderate-risk participants (Table 3), except BMI, which was lower in the 2-hour group (2-hour, 24.88 ± 5.36; 3-hour, 26.19 ± 6.28; 4-hour, 26.03 ± 6.15; P = 0.053) and except wet observations, which were more frequent among those allocated to 2- rather than 3- or 4-hour turning (P < 0.001). High-risk participants did not differ by turning group except for wet observations, which occurred more frequently in the 2-hour group than in 3- or 4-hour groups (P < 0.001) (Table 5). The overall mean percentage of meals eaten during the study was 75.1% (±21.6 %); high-risk participants ate significantly less than moderate-risk participants (P = 0.004).

Table 3:

Demographic and Risk-Status Characteristics for Moderate-Risk Participants Allocated to 2-, 3-, or 4-Hour Turning (United States and Canadian Data Combined)

| Variable | Moderate Risk (n = 617) | Mean (SD) or % | 2-Hour (n = 210) | Mean (SD) or % | 3-Hour (n = 210) | Mean (SD) or % | 4-Hour (n = 210) | Mean (SD) or % | Moderate-Risk P Values (Random Group Comparison) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 615 | 85.24 (7.65) | 210 | 85.60 (7.77) | 208 | 84.35 (7.75) | 197 | 85.80 (7.36) | 0.114a |

| BMI (measured as kg/m2) | 598 | 25.69 (5.95) | 206 | 24.88 (5.36) | 201 | 26.19 (6.28) | 191 | 26.03 (6.15) | 0.053a |

| Braden Total Score | 613 | 13.57 (0.50) | 209 | 13.58 (0.49) | 207 | 13.56 (0.56) | 197 | 13.56 (0.50) | 0.888a |

| Sensory perception | 613 | 2.88 (0.58) | 209 | 2.93 (0.61) | 207 | 2.83 (0.56) | 197 | 2.87 (0.55) | 0.166a |

| Moisture | 613 | 2.16 (0.63) | 209 | 2.17 (0.62) | 207 | 2.12 (0.64) | 197 | 2.20 (0.64) | 0.418a |

| Activity | 613 | 2.07 (0.33) | 209 | 2.07 (0.29) | 207 | 2.07 (0.37) | 197 | 2.06 (0.32) | 0.874a |

| Mobility | 613 | 2.21 (0.46) | 209 | 2.21 (0.47) | 207 | 2.23 (0.46) | 197 | 2.20 (0.44) | 0.845a |

| Nutrition | 613 | 2.75 (0.61) | 209 | 2.71 (0.62) | 207 | 2.81 (0.56) | 197 | 2.73 (0.64) | 0.235a |

| Friction | 613 | 1.50 (0.50) | 209 | 1.49 (0.51) | 207 | 1.51 (0.50) | 197 | 1.51 (0.50) | 0.944a |

| Mean percentage of meals eaten over study | 616 | 76.53 (20.94) | 210 | 75.81 (20.91) | 209 | 77.03 (20.46) | 197 | 76.75 (21.54) | 0.823a |

| All data severity | 610 | 24.70 (19.83) | 208 | 25.85 (20.13) | 206 | 24.72 (19.85) | 196 | 23.47 (19.50) | 0.486a |

| Wet times/day | 617 | 4.04 (1.58) | 210 | 4.55 (1.72) | 209 | 4.05 (1.42) | 198 | 3.49 (1.41) | <0.001a |

| Women | 464 | 75.20 | 156 | 74.29 | 155 | 74.16 | 153 | 77.27 | 0.715 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||||

| White | 506 | 82.01 | 178 | 84.67 | 175 | 83.73 | 153 | 77.27 | 0.225 |

| Black | 37 | 6.00 | 12 | 5.71 | 7 | 3.35 | 18 | 9.09 | |

| Asian | 59 | 9.56 | 16 | 7.62 | 20 | 9.57 | 23 | 11.62 | |

| Hispanic | 14 | 2.27 | 4 | 1.90 | 6 | 2.87 | 4 | 2.02 | |

| Other | 1 | 0.16 | 0 | 0.00 | 1 | 0.48 | 0 | 0.00 | |

| Diagnosis category | |||||||||

| Dementia | 421 | 69.02 | 140 | 67.31 | 142 | 68.93 | 139 | 70.92 | |

| Cerebrovascular | 216 | 35.41 | 73 | 35.10 | 80 | 38.83 | 63 | 32.14 | |

| Diabetes | 173 | 28.36 | 61 | 29.33 | 63 | 30.58 | 49 | 25.00 | |

| Cardiovascular | 491 | 80.49 | 161 | 77.40 | 171 | 83.01 | 159 | 81.12 | |

| Musculoskeletal | 333 | 54.59 | 118 | 56.73 | 102 | 49.51 | 113 | 57.65 | |

| Thyroid disorder | 111 | 18.20 | 39 | 18.75 | 36 | 17.48 | 36 | 18.37 | |

| Nutritional | 5 | 0.82 | 2 | 0.96 | 1 | 0.49 | 2 | 1.02 | |

| Admission eligibility | |||||||||

| Long stay | 527 | 85.41 | 181 | 86.19 | 176 | 84.21 | 170 | 85.86 | 0.829 |

| Short stay | 90 | 14.59 | 29 | 13.81 | 33 | 15.79 | 28 | 14.14 | |

| Country | |||||||||

| Canada | 336 | 54.46 | 114 | 54.29 | 112 | 53.59 | 110 | 55.56 | 0.922 |

| United States | 281 | 45.54 | 96 | 45.71 | 97 | 46.41 | 88 | 44.44 | |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation.

Analysis of variance performed.

Table 5:

Demographic and Risk Status Characteristics for High-Risk Participants Allocated to 2-, 3-, or 4-Hour Turning (United States and Canadian Data Combined)

| Variable | High Risk (n = 325) | Mean (SD) or % | 2-Hour (n = 111) | Mean (SD) or % | 3-Hour (n = 117) | Mean (SD) or % | 4-Hour (n = 97) | Mean (SD) or % | High-Risk P Values (Random Group Comparison) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 324 | 84.75 (7.69) | 111 | 84.77 (7.78) | 117 | 84.35 (7.79) | 96 | 85.22 (7.50) | 0.715a |

| BMI (measured as kg/m2) | 307 | 23.99 (6.06) | 107 | 24.25 (5.54) | 107 | 24.48 (7.55) | 93 | 23.11 (4.49) | 0.240a |

| Braden Total Score | 318 | 11.44 (0.73) | 109 | 11.48 (0.70) | 113 | 11.42 (0.73) | 96 | 11.42 (0.76) | 0.808a |

| Sensory perception | 318 | 2.21 (0.55) | 109 | 2.19 (0.54) | 113 | 2.20 (0.58) | 96 | 2.25 (0.54) | 0.740a |

| Moisture | 318 | 1.76 (0.64) | 109 | 1.80 (0.68) | 113 | 1.70 (0.63) | 96 | 1.79 (0.61) | 0.441a |

| Activity | 318 | 1.94 (0.25) | 109 | 1.94 (0.25) | 113 | 1.95 (0.26) | 96 | 1.94 (0.24) | 0.939a |

| Mobility | 318 | 1.77 (0.48) | 109 | 1.79 (0.47) | 113 | 1.74 (0.48) | 96 | 1.78 (0.49) | 0.750a |

| Nutrition | 318 | 2.54 (0.72) | 109 | 2.53 (0.71) | 113 | 2.61 (0.74) | 96 | 2.47 (0.70) | 0.359a |

| Friction | 318 | 1.21 (0.41) | 109 | 1.23 (0.42) | 113 | 1.22 (0.42) | 96 | 1.19 (0.39) | 0.747a |

| Mean percentage of meals eaten over study | 325 | 72.29 (22.66) | 111 | 72.16 (23.27) | 117 | 73.68 (22.44) | 97 | 70.76 (22.35) | 0.643a |

| All data severity | 317 | 26.30 (23.92) | 107 | 27.37 (25.27) | 114 | 27.69 (25.10) | 96 | 23.44 (20.70) | 0.373a |

| Wet times/day | 325 | 4.43 (1.57) | 111 | 4.94 (2.02) | 117 | 4.41 (1.33) | 97 | 3.86 (0.94) | <0.001a |

| Women | 267 | 82.15 | 92 | 82.88 | 97 | 82.91 | 78 | 80.41 | 0.867 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||||

| White | 252 | 77.54 | 86 | 77.48 | 93 | 79.49 | 73 | 75.26 | 0.655 |

| Black | 18 | 5.54 | 3 | 2.70 | 7 | 5.98 | 8 | 8.25 | |

| Asian | 42 | 12.92 | 18 | 16.22 | 12 | 10.26 | 12 | 12.37 | |

| Hispanic | 8 | 2.46 | 2 | 1.80 | 4 | 3.42 | 2 | 2.06 | |

| Other | 5 | 1.54 | 2 | 1.80 | 1 | 0.85 | 2 | 2.06 | |

| Diagnosis category | |||||||||

| Dementia | 251 | 79.18 | 83 | 77.57 | 91 | 79.82 | 77 | 80.21 | |

| Cerebrovascular | 125 | 39.43 | 45 | 42.06 | 43 | 37.72 | 37 | 38.54 | |

| Diabetes | 79 | 24.92 | 26 | 24.30 | 29 | 25.44 | 24 | 25.00 | |

| Cardiovascular | 222 | 70.03 | 83 | 77.57 | 78 | 68.42 | 61 | 63.54 | |

| Musculoskeletal | 173 | 54.57 | 60 | 56.07 | 57 | 50.00 | 56 | 58.33 | |

| Thyroid disorder | 56 | 17.67 | 23 | 21.50 | 15 | 13.16 | 18 | 18.75 | |

| Nutritional | 13 | 4.10 | 7 | 6.54 | 2 | 1.75 | 4 | 4.17 | |

| Admission eligibility | |||||||||

| Long stay | 287 | 88.31 | 94 | 84.68 | 103 | 88.03 | 90 | 92.78 | 0.192 |

| Short stay | 38 | 11.69 | 17 | 15.32 | 14 | 11.97 | 7 | 7.22 | |

| Country | |||||||||

| Canada | 169 | 52.00 | 49 | 44.14 | 58 | 49.57 | 62 | 63.92 | 0.014 |

| United States | 156 | 48.00 | 62 | 55.86 | 59 | 50.43 | 35 | 36.08 | |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation.

Analysis of variance performed.

Table 4:

Demographic and Risk Status Characteristics for Moderate-Risk Participants Allocated to 2-, 3-, or 4-Hour Turning (Ontario Data Only)

| Variable | Moderate Risk | Mean (SD) or % | 2-Hour | Mean (SD) or % | 3-Hour | Mean (SD) or % | 4-Hour | Mean (SD) or % | Moderate-Risk P Values (Random Group Comparison) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 336 | 86.06 (7.26) | 114 | 85.52 (7.71) | 112 | 85.63 (7.30) | 110 | 87.06 (6.68) | 0.208a |

| BMI (measured as kg/m2) | 335 | 25.08 (5.62) | 113 | 23.86 (4.89) | 112 | 25.40 (6.11) | 110 | 25.99 (5.62) | 0.013a |

| Braden Total Score | 336 | 13.60 (0.49) | 114 | 13.61 (0.49) | 112 | 13.59 (0.49) | 110 | 13.61 (0.49) | 0.950a |

| Sensory perception | 336 | 2.94 (0.59) | 114 | 3.05 (0.64) | 112 | 2.85 (0.59) | 110 | 2.92 (0.53) | 0.030a |

| Moisture | 336 | 2.11 (0.55) | 114 | 2.13 (0.52) | 112 | 2.07 (0.51) | 110 | 2.14 (0.61) | 0.619a |

| Activity | 336 | 2.07 (0.28) | 114 | 2.04 (0.18) | 112 | 2.10 (0.35) | 110 | 2.06 (0.28) | 0.242a |

| Mobility | 336 | 2.21 (0.45) | 114 | 2.18 (0.43) | 112 | 2.24 (0.49) | 110 | 2.19 (0.42) | 0.582a |

| Nutrition | 336 | 2.84 (0.56) | 114 | 2.79 (0.59) | 112 | 2.88 (0.55) | 110 | 2.85 (0.56) | 0.437a |

| Friction | 336 | 1.43 (0.50) | 114 | 1.41 (0.49) | 112 | 1.45 (0.50) | 110 | 1.45 (0.50) | 0.842a |

| Mean percentage of meals eaten over study | 336 | 83.67 (16.09) | 114 | 81.92 (17.93) | 112 | 85.47 (13.66) | 110 | 83.66 (16.31) | 0.253a |

| All data severity | 336 | 21.85 (15.23) | 114 | 23.86 (17.69) | 112 | 20.99 (14.40) | 110 | 20.65 (13.08) | 0.222a |

| Wet times/day | 336 | 3.95 (1.14) | 114 | 4.32 (1.19) | 112 | 3.95 (0.96) | 110 | 3.56 (1.12) | <0.001a |

| Women | 244 | 72.62 | 81 | 71.05 | 81 | 72.32 | 82 | 74.55 | 0.839 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||||

| White | 262 | 77.98 | 92 | 80.70 | 91 | 81.25 | 79 | 71.82 | 0.318 |

| Black | 12 | 3.57 | 4 | 3.51 | 1 | 0.89 | 7 | 6.36 | |

| Asian | 57 | 16.96 | 16 | 14.04 | 19 | 16.96 | 22 | 20.00 | |

| Hispanic | 5 | 1.49 | 2 | 1.75 | 1 | 0.89 | 2 | 1.82 | |

| Other | |||||||||

| Diagnosis category | |||||||||

| Dementia | 223 | 66.37 | 72 | 63.16 | 74 | 66.07 | 77 | 70.00 | |

| Cerebrovascular | 136 | 40.48 | 48 | 42.11 | 49 | 43.75 | 39 | 35.45 | |

| Diabetes | 86 | 25.60 | 32 | 28.07 | 29 | 25.89 | 25 | 22.73 | |

| Cardiovascular | 244 | 72.62 | 80 | 70.18 | 87 | 77.68 | 77 | 70.00 | |

| Musculoskeletal | 188 | 55.95 | 66 | 57.89 | 55 | 49.11 | 67 | 60.91 | |

| Thyroid disorder | 49 | 14.58 | 19 | 16.67 | 11 | 9.82 | 19 | 17.27 | |

| Nutritional | |||||||||

| Admission eligibility | |||||||||

| Long stay | 312 | 92.86 | 111 | 97.37 | 100 | 89.29 | 101 | 91.82 | 0.054 |

| Short stay | 24 | 7.14 | 3 | 2.63 | 12 | 10.71 | 9 | 8.18 | |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation.

Analysis of variance performed.

Table 6:

Demographic and Risk Status Characteristics for High-Risk Participants Allocated to 2-, 3-, or 4-Hour Turning (Ontario Data Only)

| Variable | High Risk | Mean (SD) or % | 2-Hour | Mean (SD) or % | 3-Hour | Mean (SD) or % | 4-Hour | Mean (SD) or % | High-Risk P Values (Random Group Comparison) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 169 | 85.59 (7.61) | 49 | 86.27 (7.61) | 58 | 84.76 (8.00) | 62 | 85.82 (7.29) | 0.570a |

| BMI (measured as kg/m2) | 166 | 22.68 (4.80) | 49 | 22.66 (4.91) | 57 | 22.78 (5.09) | 60 | 22.61 (4.50) | 0.983a |

| Braden Total Score | 168 | 11.48 (0.74) | 49 | 11.49 (0.74) | 57 | 11.46 (0.73) | 62 | 11.48 (0.76) | 0.969a |

| Sensory perception | 168 | 2.19 (0.59) | 49 | 2.20 (0.54) | 57 | 2.18 (0.66) | 62 | 2.19 (0.57) | 0.968a |

| Moisture | 168 | 1.90 (0.56) | 49 | 1.94 (0.56) | 57 | 1.86 (0.61) | 62 | 1.90 (0.53) | 0.772a |

| Activity | 168 | 1.98 (0.15) | 49 | 1.96 (0.20) | 57 | 1.98 (0.13) | 62 | 1.98 (0.13) | 0.654a |

| Mobility | 168 | 1.68 (0.49) | 49 | 1.65 (0.48) | 57 | 1.68 (0.51) | 62 | 1.71 (0.49) | 0.835a |

| Nutrition | 168 | 2.58 (0.70) | 49 | 2.63 (0.73) | 57 | 2.65 (0.69) | 62 | 2.48 (0.67) | 0.366a |

| Friction | 168 | 1.14 (0.35) | 49 | 1.10 (0.31) | 57 | 1.11 (0.31) | 62 | 1.21 (0.41) | 0.169a |

| Mean percentage of meals eaten over study | 169 | 77.24 (21.33) | 49 | 77.52 (20.28) | 58 | 76.93 (22.94) | 62 | 77.30 (20.91) | 0.990a |

| All data severity | 168 | 20.86 (17.95) | 49 | 19.31 (16.41) | 58 | 22.29 (17.60) | 61 | 20.74 (19.56) | 0.693a |

| Wet times/day | 169 | 4.14 (0.97) | 49 | 4.71 (1.11) | 58 | 4.15 (0.76) | 62 | 3.69 (0.77) | <0.001a |

| Women | 140 | 82.84 | 45 | 91.84 | 49 | 84.48 | 46 | 74.19 | 0.046 |

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||||

| White | 117 | 69.23 | 28 | 57.14 | 43 | 74.14 | 46 | 74.19 | 0.176 |

| Black | 9 | 5.33 | 2 | 4.08 | 3 | 5.17 | 4 | 6.45 | |

| Asian | 40 | 23.67 | 16 | 32.65 | 12 | 20.69 | 12 | 19.35 | |

| Hispanic | 1 | 0.59 | 1 | 2.04 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | |

| Other | 2 | 1.18 | 2 | 4.08 | 0 | 0.00 | 0 | 0.00 | |

| Diagnosis category | |||||||||

| Dementia | 138 | 82.14 | 38 | 77.55 | 48 | 82.76 | 52 | 85.25 | |

| Cerebrovascular | 73 | 43.45 | 21 | 42.86 | 25 | 43.10 | 27 | 44.26 | |

| Diabetes | 35 | 20.83 | 7 | 14.29 | 14 | 24.14 | 14 | 22.95 | |

| Cardiovascular | 104 | 61.90 | 35 | 71.43 | 32 | 55.17 | 37 | 60.66 | |

| Musculoskeletal | 97 | 57.74 | 32 | 65.31 | 27 | 46.55 | 38 | 62.30 | |

| Thyroid disorder | 26 | 15.48 | 11 | 22.45 | 7 | 12.07 | 8 | 13.11 | |

| Nutritional | 2 | 1.19 | 1 | 2.04 | 1 | 1.72 | 0 | 0.00 | |

| Admission eligibility | |||||||||

| Long stay | 161 | 95.27 | 46 | 93.88 | 57 | 98.28 | 58 | 93.55 | 0.411 |

| Short stay | 8 | 4.73 | 3 | 6.12 | 1 | 1.72 | 4 | 6.45 | |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index; SD, standard deviation.

Analysis of variance performed.

Pressure ulcers developed on the coccyx or sacrum (n = 16), trochanter (n = 1), or heels (n = 2) of 19 of 942 (2.02%) participants. Pressure ulcers were limited to superficial stage 1 (n = 1) and stage 2 (n = 18) ulcers. One participant's condition deteriorated and 2 developed ulcers, one of which could have become a deep tissue injury; this patient was withdrawn from the study. Otherwise, no stage 3, stage 4, or unstageable ulcers developed (Table 7). Overall, there was no significant difference in PrU incidence (P = 0.68) between groups (2-hour, 8/321 [2.49%] ulcers/group; 3-hour, 2/326 [0.61%]; 4-hour, 9/295 [3.05%]). Pressure ulcers among high-risk (6/325, 1.85%) versus moderate-risk (13/617, 2.11%) participants were not significantly different (P = 0.79), nor between moderate-risk (P = 0.68) or high-risk (P = 0.90) allocation groups. When short-stay (≤7 days) or long-stay (≤90 days) admissions and allocation groups were compared, no significant differences were apparent.

Table 7:

Incidence of Pressure Ulcers Overall, by Risk-Group Stratification and by Allocation to Turning Frequency (United States and Canadian Data Combined)

| Group | Ulcers/Group (%) | Ulcers/2-Hour Turning (%) | Ulcers/3-Hour Turning (%) | Ulcers/4-Hour Turning (%) | Random Group Comparison (P) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All subjects | 19/942 (2.02) | 8/321 (2.49) | 2/326 (0.61) | 9/295 (3.05) | 0.68 |

| Moderate risk | 13/617 (2.11) | 6/210 (2.86) | 0/209 (0.0) | 7/198 (3.54) | 0.68 |

| High risk | 6/325 (1.85) | 2/111 (1.80) | 2/117 (1.71) | 2/97 (2.06) | 0.90 |

| Moderate vs. high risk | 1.00 |

Table 8:

Incidence of Pressure Ulcers Overall, by Risk-Group Stratification and by Allocation to Turning Frequency (Ontario Data Only)

| Group | Ulcers/Group (%) | Ulcers/2-Hour Turning (%) | Ulcers/3-Hour Turning (%) | Ulcers/4-Hour Turning (%) | Random Group Comparison (P) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All subjects | 10/505 (1.98) | 4/163 (2.45) | 2/170 (1.18) | 4/172 (2.33) | 0.95 |

| Moderate risk | 5/336 (1.49) | 2/114 (1.75) | 0/112 (0.00) | 3/110 (2.73) | 0.57 |

| High risk | 5/169 (2.96) | 2/49 (4.08) | 2/58 (3.45) | 1/62 (1.61) | 0.44 |

| Moderate vs. High Risk | 0.26 |

Logistic regressions predicting PrU development were computed for the total population, and separately for moderate- and high-risk groups, allowing determination of a Braden Scale risk level on admission. Severity scores, country, BMI, age, diagnosis groups, mean percentage of meals eaten and mean wet episodes were entered into regression models (Table 9). Pressure ulcer development was significantly related to a diagnosis of nutritional deficiency among the total and moderate-risk participants. The only variable predicting PrU in the high-risk population was fracture diagnosis.

Table 9:

Regression Analysis Predicting Pressure Ulcer Development (United States and Canadian Data Combined)

| Independent Variable | Total Population (N = 942) (c = .681) | Total Moderate-Risk Population (n = 617) (c = .583) | Total High-Risk Population (n = 325) (c = .685) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | Odds Ratio | P | C | Odds Ratio | P | C | Odds Ratio | P | |

| Intercept | −3.298 2 |

<0.0001 | −4.5005 | <0.0001 | −4.4998 | <0.0001 | |||

| Fracture diagnosis | 1.9095 | 6.75 | 0.022 | ||||||

| 3-Hour turn | −1.521 6 |

0.218 | 0.0428 | ||||||

| Cerebrovascular accident diagnosis | −1.288 5 |

0.276 | 0.0866 | ||||||

| Severity score | 0.0205 | 1.021 | 0.0538 | ||||||

| Nutritional diagnosis | 2.8657 | 17.56 | 0.0153 | ||||||

Abbreviations: c, regression model concordance; C, coefficient.

Table 10:

Regression Analysis Predicting Pressure Ulcer Development (Ontario Data Only)

| Independent Variable | Total Population (n = 505) | Total Moderate-Risk Population (n = 336) (c = .638) | Total High-Risk Population (n = 169) (c = .654) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | Odds Ratio | P | C | Odds Ratio | P | C | Odds Ratio | P | |

| Intercept | −3.9 | <0.0001 | −5.3488 | <0.0001 | −3.898 | <0.0001 | |||

| Fracture diagnosis | 1.8837 | 6.578 | 0.0479 | ||||||

| 3-Hour turn | 0.0421 | 1.043 | 0.0648 | ||||||

Abbreviations: c, regression model concordance; C, coefficient.

Discussion

Demographic characteristics of participants in the Turning for Ulcer Reduction Study (TURN Study) were similar to 3 previous studies of repositioning completed in Belgium and Ireland, with mostly white (80%), female participants (77% to 87%), and ranging in mean age from 85 to 87 years. (12–15)

The incidence of PrUs in the TURN Study was low (2.02%) among the moderate- and high-risk participants allocated to 3 turning intervals. Further, only superficial (stages 1 and 2) ulcers developed (with one potential deep tissue injury on a participant who became terminally ill and was removed from the study) and no stages 3 and 4 ulcers. There was no significant difference in PrU development between high- and moderate-risk residents, or among moderate- and high-risk residents allocated to 2-, 3-, or 4- hour turning. The 2.02% incidence is consistent among moderate- and high-risk subjects with the incidence of PrU among low-risk, long-stay residents (2%) in United States nursing facilities, and is considerably lower than the 10% prevalence reported among high-risk, long-stay residents. (9)

Considering only 2-, 3-, 4-, or 6-hour turning intervals (15)in previous randomized studies of turning (Table 11), the low incidence of PrUs in the TURN Study is similar to the 3% (2 ulcers/66 participants) incidence reported by Defloor and Grypdonck (15) for the 4-hour turning group on viscoelastic mattresses, and is similar to the 2% (2 ulcers/99 participants) incidence reported by Moore et al (13) for those on powered mattresses who were turned every 3 hours. The incidence of stages 2 to 4 PrUs reported by Defloor and Grypdonck (15), Moore et al (13), and Vanderwee et al (12) in the comparison groups without high-density foam mattresses or longer turning intervals ranged from 14.3% to 24.1%. No stages 3 or 4 PrUs were reported in the TURN Study or in the 4-hour turning groups of Defloor et al (14) and Moore et al (13), suggesting that longer turning intervals, powered beds, spring mattresses, and overlays do not protect against PrUs as well as high-density foam mattresses do.

Table 11:

Comparison of Pressure Ulcer Risk, Support Surface, and Incidence of Grades 2 to 4 Ulcers by Turning Frequency in 4 Randomized Controlled Trials

| Study | Braden Scale Score | Support Surface | 2-Hour | 3-Hour | 4-Hour | 6-Hour |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Defloor et al (14) | Mean 13.0 ± 2 | Standard viscoetastic mattress | 9/63 (14%) | 14/58 (24%) | Stage 2 2/66 (3%) | Stage 2 10/63 (15.9%) |

| Vanderwee et al (12) | Mean 15.0 ± 3 | Viscoelastic foam overlay (7 cm), not high-density foam mattress | Stage 2 17/122 (13.9%), Stages 3 or 4 (2.5%) | Stage 2 22/113 (19.5%), Stages 3 or 4 (1.8%) | ||

| Moore et al (13) | Activity and mobility subscales | 99% had powered pressure redistribution device | 2/99 (2%) | 7/114 (6%) | ||

| TURN Study | Moderate (13–14), High (10–12) | Viscoelastic, high-density foam mattresses | Moderate: 6/210 (2.86%) High: 2/111 (1.8%) | Moderate: 0/209 (0.00%) High: 2/117 (1.71%) | Moderate: 7/198 (3.54%) High: 2/97 (2.06%) |

Abbreviation: TURN, Turning for Ulcer Reduction.

Overall, results of the TURN Study support turning moderate- and high-risk residents at intervals of 2, 3, or 4 hours when they are cared for on high-density foam mattresses. Turning at 3- and 4-hour intervals is no worse than the current practice of turning every 2 hours in United States and Canadian LTC facilities. Two-hour turning could expose residents to increased risk from friction during repositioning.

The 4-hour turning result of few superficial and no deeper ulcers is consistent with the result in Defloor et al (14), and 4-hour frequency should be considered for implementation in nursing facilities. This recommendation, however, requires caution. First, in the protocols of the TURN and Defloor et al (14) studies, high-density foam mattresses replaced older, spring-type mattresses. Replacing old mattresses with high-density foam mattresses is an important system change and is a prerequisite for changing turning frequency.

Second, participants were at moderate and high risk on the Braden Scale, suggesting that the findings of this study might be limited to these risk levels. Most studies of risk assessment to date are limited to testing existing prognostic tools or creating new or better tools. (12, 16–20) These studies of turning frequency demonstrate the clinical utility of the Braden Scale.

Third, the overall quality of care in the TURN, Defloor et al (14), Vanderwee et al (12), and Moore et al (13) studies was identified as “guideline-based” care delivered by facility nursing staff to prevent PrUs with specific mention of protecting and elevating heels, providing incontinence care, and meeting nutritional needs.

Fourth, vigilant assessment of skin likely reduced the incidence of deep ulcers in the TURN and other studies. (8) As guidelines are developed in which turning recommendations go from the traditional 2- to 3- hour turning to 3- to 4- hour turning, skin observations could ensure that early signs of PrUs are noted.

Conclusions

Residents of high-performing nursing facilities who are at moderate or high risk of PrUs according to the Braden Scale may be turned at 3- or 4-hour intervals if they are cared for on high-density foam replacement mattresses. Clinicians should follow best-practice guidelines and be observant of skin changes, modifying turning frequency if skin changes are observed. These findings, reported as similar for subjects in 3 countries, have important implications for improving quality of life by permitting residents to sleep for longer intervals. In a broader sense, these findings will likely influence first, public policy and regulations regarding the frequency of turning for preventing PrUs; and second, reallocation of staff time spent repositioning patients every 2 hours to activities that improve residents’ quality of life, such as increased assistance at mealtime, mobilization, toileting, and social engagement.

References

- 1.Kosiak M. Etiology of decubitus ulcers. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1961. Jan; 42: 19–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindan O. Etiology of decubitus ulcers: an experimental study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1961. Nov; 42: 774–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li Y, Yin J, Cai X, Temkin-Greener J, Mukamel DB. Association of race and sites of care with pressure ulcers in high-risk nursing home residents. JAMA. 2011. Jul 13; 306(2): 179–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bergstrom N, Horn SD. Racial disparities in rates of pressure ulcers in nursing homes and site of care. JAMA. 2011. Jul 13; 306(2): 211–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bates-Jensen BM, Cadogan M, Osterweil D, Levy-Storms L, Jorge J, Al-Samarrai N, et al. The minimum data set pressure ulcer indicator: does it reflect differences in care processes related to pressure ulcer prevention and treatment in nursing homes? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2003. Sep; 51(9): 1203–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bergstrom N, Braden BJ, Laguzza A, Holman V. The Braden Scale for Predicting Pressure Sore Risk. Nurs Res. 1987. Jul-Aug; 36(4): 205–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bergstrom N, Braden B, Kemp M, Champagne M, Ruby E. Predicting pressure ulcer risk: a multisite study of the predictive validity of the Braden Scale. Nurs Res. 1998. Sep-Oct; 47(5): 261–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bergstrom N, Braden B. A prospective study of pressure sore risk among institutionalized elderly. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1992. Aug; 40(8): 747–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Nursing Home Compare. 2007. [updated 2007; cited 2011 March 12]; Available from: http://www.medicare.gov/NursingHomeCompare/search.aspx?bhcp=1.

- 10.Bergstrom N, Allman R, Carlson C, et al. Pressure ulcers in adults: prediction and prevention. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Am Fam Physician. 1992. Sep; 46(3): 787–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel and National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel. Prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers: quick reference guide. Washington DC; European Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel and National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vanderwee K, Grypdonck MH, De Bacquer D, Defloor T. Effectiveness of turning with unequal time intervals on the incidence of pressure ulcer lesions. J Adv Nurs. 2007. Jan; 57(1): 59–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moore Z, Cowman S, Conroy RM. A randomised controlled clinical trial of repositioning, using the 30 degrees tilt, for the prevention of pressure ulcers. J Clin Nurs. 2011. Sep; 20 (17–18): 2633–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Defloor T, De Bacquer D, Grypdonck MH. The effect of various combinations of turning and pressure reducing devices on the incidence of pressure ulcers. Int J Nurs Stud. 2005. Jan; 42(1): 37–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Defloor T, Grypdonck MF. Pressure ulcers: validation of two risk assessment scales. J Clin Nurs. 2005. Mar; 14(3): 373–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pancorbo-Hidalgo PL, Garcia-Fernandez FP, Lopez-Medina IM, Alvarez-Nieto C. Risk assessment scales for pressure ulcer prevention: a systematic review. J Adv Nurs. 2006. Apr; 54(1): 94–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Anthony D, Parboteeah S, Saleh M, Papanikolaou P. Norton, Waterlow and Braden scores: a review of the literature and a comparison between the scores and clinical judgement. J Clin Nurs. 2008. Mar; 17(5): 646–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bergquist-Beringer S, Gajewski BJ. Outcome and assessment information set data that predict pressure ulcer development in older adult home health patients. Adv Skin Wound Care. 201. Sep; 24(9): 404–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lahmann NA, Tannen A, Dassen T, Kottner J. Friction and shear highly associated with pressure ulcers of residents in long-term care – Classification Tree Analysis (CHAID) of Braden items. J Eval Clin Pract. 2011. Feb; 17(1): 168–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Takahashi PY, Chandra A, Cha SS. Risk factors for pressure ulceration in an older community-dwelling population. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2011. Feb; 24(2): 72–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]