Abstract

Background

End-of-life care is a complex service. The education of health care providers, patients nearing end of life, and informal caregivers plays a vital role in increasing knowledge about the care options available. This review looks at whether education helps improve outcomes for patients nearing the end of life and for their informal caregivers.

Objectives

To systematically review and study the effectiveness of educational interventions for health care providers, patients nearing the end of life, and informal caregivers to improve patient and informal caregiver outcomes.

Data Sources

We performed a literature search using Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid MEDLINE In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations, Ovid Embase, Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and EBM Reviews for studies published from January 1, 2003, to October 31, 2013.

Review Methods

We conducted this review according to published guidelines and using a prespecified protocol. We included primary studies that evaluated any educational intervention in end-of-life care for health care providers, patients, or informal caregivers and measured patient or informal caregiver quality of life using validated scales.

Results

The database search yielded 2,468 citations; we included 6 studies in the review. Studies reported on educational interventions for health care providers, patients nearing the end of life, and informal caregivers. After an educational intervention, patients nearing the end of life had better symptom control and informal caregivers had improved quality of life. However, there was no significant change in patient quality of life or pain control, or in informal caregiver or health care provider satisfaction. There was no decrease in resource utilization.

Limitations

Most studies did not report data adequately, did not define “routine care” and were not blinded. Allocation concealment was also inadequately reported.

Conclusions

Based on moderate quality evidence, education of health care providers, patients nearing the end of life, and informal caregivers improved patient symptom control and informal caregiver quality of life.

Plain Language Summary

End-of-life care is complicated. It is important for health care providers, other care givers, and patients nearing the end of life to know what options are available for end-of-life care. This review looks at whether education helps make things better for patients nearing the end of life, as well as for their caregivers. We found that education improved patients’ symptom control and caregivers’ quality of life. Education did not improve patients’ quality of life, and it did not improve health care provider or caregiver satisfaction. We did not find evidence that education reduces emergency department visits, admissions to intensive care, or the number of days in hospital.

Background

In July 2013, the Evidence Development and Standards (EDS) branch of Health Quality Ontario (HQO) began work on developing an evidentiary framework for end of life care. The focus was on adults with advanced disease who are not expected to recover from their condition. This project emerged from a request by the Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care that HQO provide them with an evidentiary platform on strategies to optimize the care for patients with advanced disease, their caregivers (including family members), and providers.

After an initial review of research on end-of-life care, consultation with experts, and presentation to the Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee (OHTAC), the evidentiary framework was produced to focus on quality of care in both the inpatient and the outpatient (community) settings to reflect the reality that the best end-of-life care setting will differ with the circumstances and preferences of each client. HQO identified the following topics for analysis: determinants of place of death, patient care planning discussions, cardiopulmonary resuscitation, patient, informal caregiver and healthcare provider education, and team-based models of care. Evidence-based analyses were prepared for each of these topics.

HQO partnered with the Toronto Health Economics and Technology Assessment (THETA) Collaborative to evaluate the cost-effectiveness of the selected interventions in Ontario populations. The economic models used administrative data to identify an end-of-life population and estimate costs and savings for interventions with significant estimates of effect. For more information on the economic analysis, please contact Murray Krahn at murray.krahn@theta.utoronto.ca.

The End-of-Life mega-analysis series is made up of the following reports, which can be publicly accessed at http://www.hqontario.ca/evidence/publications-and-ohtac-recommendations/ohtas-reports-and-ohtac-recommendations.

-

▸

End-of-Life Health Care in Ontario: OHTAC Recommendation > Health Care for People Approaching the End of Life: An Evidentiary Framework

-

▸

Effect of Supportive Interventions on Informal Caregivers of People at the End of Life: A Rapid Review

-

▸

Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation in Patients with Terminal Illness: An Evidence-Based Analysis

-

▸

The Determinants of Place of Death: An Evidence-Based Analysis

-

▸

Educational Intervention in End-of-Life Care: An Evidence-Based Analysis

-

▸

End-of-Life Care Interventions: An Economic Analysis

-

▸

Patient Care Planning Discussions for Patients at the End of Life: An Evidence-Based Analysis

-

▸

Team-Based Models for End-of-Life Care: An Evidence-Based Analysis

Objectives of Analysis

To systematically review studies that included educational interventions for health care providers, patients nearing the end of life (EoL), and informal caregivers to improve patient and informal caregiver outcomes.

To determine the effectiveness of educational interventions for improving quality of life in patients nearing EoL and informal caregivers.

Clinical Need and Target Population

Patients nearing the end of life have a progressive, life-threatening disease and no possibility of obtaining remission, stabilization, or modification of the course of illness. (1) EoL is a difficult and highly emotional experience, not only for the patients themselves, but also for their informal caregivers and health care providers. Ideally, EoL care should make the experience much more manageable for patients and their informal caregivers. We know that education can increase one's sense of self-control and theoretical well-being, but there is very little research to show whether educating health care providers, patients nearing EoL, and their informal caregivers can improve outcomes for patients and informal caregivers.

Conceptual Framework

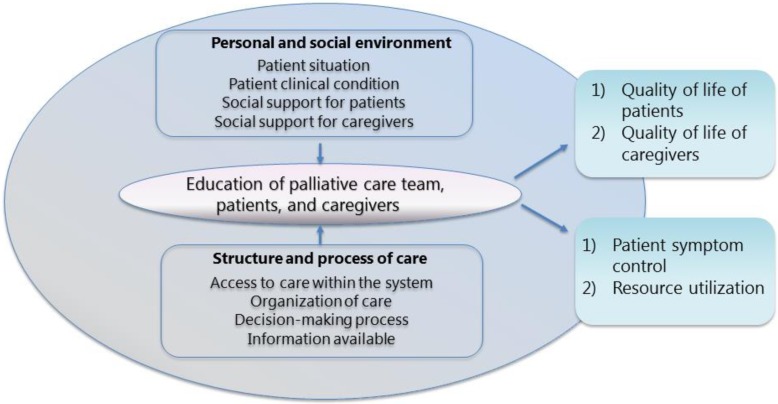

The conceptual framework in Figure 1 is derived from Stewart et al. (2) In their report, the authors discuss how the quality of life of patients nearing EoL and their informal caregivers is influenced by their personal and social environment, as well as by the structure and process of care. The patient's situation and clinical condition, along with the support they and their informal caregivers receive, affect the quality of their health care and in turn their quality of life. Variations in the health care system and how patients and informal caregivers access it may further contribute to outcomes for patients and informal caregivers. Decision-making processes, information available to the dying person, organization of care, and the patient's informal caregivers may also influence outcomes. The patient's personal and social environment and the structure and process of care become part of education, determining quality-of-life and system-level outcomes. (2)

Figure 1: Conceptual Framework.

Technology/Technique

Education is “that multidisciplinary practice, which is concerned with designing, implementing, and evaluating educational programs that enable individuals, families, groups, organizations, and communities to play active roles in achieving, protecting, and sustaining health.” (3) Health education is “any combination of learning experiences designed to facilitate voluntary actions conducive to health.” (4)

Ontario health care providers receive continuing medical education on a wide range of topics, but education on EoL care may not be provided regularly. As part of EoL care, health care providers may also need to co-ordinate education for patients nearing EoL and their informal caregivers.

Evidence-Based Analysis

Research Question

Do educational interventions in EoL care for health care providers, patients nearing the end of life, or informal caregivers improve the quality of life of patients or informal caregivers compared with usual education?

Research Methods

Literature Search

Search Strategy

A literature search was performed on December 2, 2013, using Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid MEDLINE In-Process and Other Non-Indexed Citations, Ovid Embase, EBSCO Cumulative Index to Nursing & Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), and EBM Reviews, for studies published from January 1, 2003, to October 31, 2013. (Appendix 1 provides details of the search strategies.) Abstracts were reviewed by a single reviewer and, for those studies meeting the eligibility criteria, full-text articles were obtained. Reference lists were also examined for any additional relevant studies not identified through the search.

Inclusion Criteria

English-language full-text publications

published between January 1, 2003, and October 31, 2013

randomized controlled trials and systematic reviews (with or without meta-analyses)

EoL population as defined by individual studies

studies in adult populations (patients 18 years and older)

any type of educational intervention delivered to those nearing EoL, their informal caregivers, or health care providers

Exclusion Criteria

studies in mixed EoL populations (adults and children) where data extraction was not possible

studies in pediatric populations (patients < 18 years)

EoL after acute trauma (e.g., accidents)

observational studies, case reports, editorials, letters, comments, conference abstracts, and cross-sectional studies

Outcomes of Interest

Primary Outcomes

patient quality of life as measured with a validated scale

informal caregiver quality of life as measured with a validated scale

Secondary Outcomes

patient pain control

patient symptom control

informal caregiver and health care provider satisfaction

number of hospital days and emergency department visits

intensive care unit admissions

Statistical Analysis

We analyzed data using Review Manager Version 5. (5) We pooled mean differences and standard errors from the primary studies (when available) to obtain a point estimate with 95% confidence intervals using a random effects model. (6–8) We calculated Q statistics to determine between-study heterogeneity, using alpha = 0.10 as the criterion for statistical significance. We used I2 to quantify the magnitude of heterogeneity, with values of 0% to 30%, 31% to 50%, and > 50% representing mild, moderate, and notable heterogeneity, respectively. (9) A funnel plot was constructed to check for publication bias. (10)

Quality of Evidence

The quality of the body of evidence for each outcome was examined according to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) Working Group criteria. (11) The overall quality was determined to be high, moderate, low, or very low using a step-wise, structural methodology.

Study design was the first consideration; the starting assumption was that randomized controlled trials are high quality. Five additional factors—risk of bias, inconsistency, indirectness, imprecision, and publication bias—were then taken into account. Limitations in these areas resulted in downgrading the quality of evidence. Finally, 3 main factors that may raise the quality of evidence were considered: the large magnitude of effect, the dose response gradient, and any residual confounding factors. (12) For more detailed information, please refer to the latest series of GRADE articles. (12)

As stated by the GRADE Working Group, the final quality score can be interpreted using the following definitions:

| High | High confidence in the effect estimate—the true effect lies close to the estimate of the effect |

| Moderate | Moderate confidence in the effect estimate—the true effect is likely to be close to the estimate of the effect, but may be substantially different |

| Low | Low confidence in the effect estimate—the true effect may be substantially different from the estimate of the effect |

| Very Low | Very low confidence in the effect estimate—the true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimate of the effect |

Results of Evidence-Based Analysis

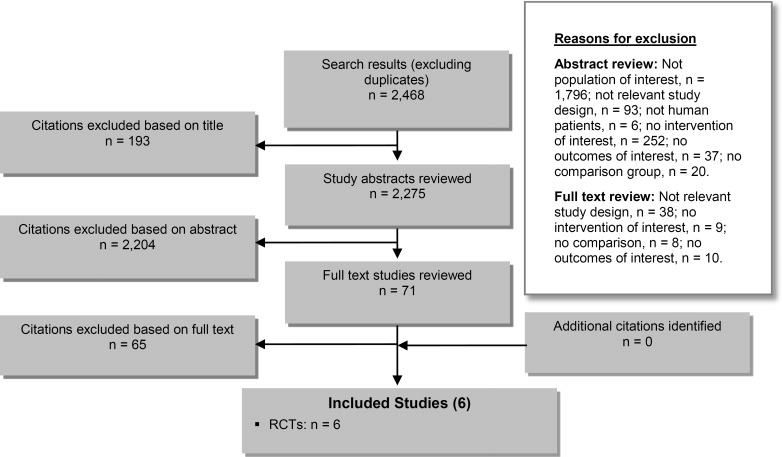

The database search yielded 2,468 citations published between January 1, 2003, and October 31, 2013 (with duplicates were removed). Articles were excluded based on information in the title and abstract. The full texts of potentially relevant articles were obtained for further assessment. Figure 2 shows the breakdown of when and for what reason citations were excluded from the analysis.

Figure 2: Citation Flow Chart.

Abbreviation: RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Six studies (all RCTs) met the inclusion criteria. The reference lists of the included studies were hand-searched to identify other relevant studies, but no additional citations were included.

For each included study, the study design was identified and is summarized below in Table 1, a modified version of a hierarchy of study design by Goodman, 1996. (13)

Table 1:

Body of Evidence Examined According to Study Design

| Study Design | Number of Eligible Studies | |

|---|---|---|

| RCTs | ||

| Systematic review of RCTs | ||

| Large RCT | 6 | |

| Small RCT | ||

| Observational Studies | ||

| Systematic review of non-RCTs with contemporaneous controls | ||

| Non-RCT with contemporaneous controls | ||

| Systematic review of non-RCTs with historical controls | ||

| Non-RCT with historical controls | ||

| Database, registry, or cross-sectional study | ||

| Case series | ||

| Retrospective review, modelling | ||

| Studies presented at an international conference | ||

| Expert opinion | ||

| Total | 6 | |

Abbreviation: RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Study Characteristics

Table 2 summarizes the characteristics of the included studies.

Table 2:

Characteristics of the Included Studies

| Author, Year | Country | Sample Size, N | EoL Population | Mean Age, y (SD) I/C | Male, n (%) I/C | Patient Care Setting |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pelayo-Alvarez et al, 2013 (14) | Spain | 117 | Advanced cancer | 69 (1) / 70 (11) | 39 (62) / 31 (57) | Primary care |

| Curtis et al, 2013 (15) | United States | 1,717 | Advanced chronic diseasea | 65 (14) / 66 (14) | 455 (59) / 534 (56) | Hospital |

| Curtis et al, 2011 (16)b | United States | 396 | Advanced chronic diseasea | 58 (15) / 59 (15) | 66 (37) / 55 (26) | Hospital |

| Meyers et al, 2011 (17) | United States | 441 | Advanced cancer | NR / NR | NR / NR | Hospital |

| Bakitas et al, 2009 (18) | United States | 279 | Advanced cancer | 65 (10) / 65 (12) | 90 (62) / 78 (58) | Hospital |

| McMillan et al, 2006 (19) | United States | 220 | Advanced cancer | 71 (11) / 70 (13) | 56 (63)/ 51 (56) | Community-dwelling, hospice care |

Abbreviations: C, control; EoL, end of life; I, intervention; NR, not reported; SD, standard deviation.

Included chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, end-stage liver disease, and terminal cancer.

Cluster randomized trial.

Educational Interventions

Table 3 describes the educational interventions used in the 6 included studies. Educational interventions were for health care providers, patients nearing EoL, or informal caregivers. Health care providers included clinicians, nurses, internal medicine residents, and palliative care fellows. Interventions were compared to usual care or usual education.

Table 3:

Educational Interventions Used in the Included Studies

| Author, Year | Intervention Population | Intervention (Domains) | Control |

|---|---|---|---|

| Educational of Health Care Providers | |||

| Pelayo-Alvarez et al, 2013 (14) | Primary care physicians | 96-hour online training program for palliative care self-training (communication) | Voluntary traditional palliative care training course |

| Curtis et al, 2013 (15) | Internal medicine residents and fellows, nurses | Brief didactic overview, skills practice using simulation, reflective discussions on palliative and EoL communication (communication) | Usual education |

| Curtis et al, 2011 (16) | Clinicians | Grand rounds, workshops, and video presentations; academic detailing of specific barriers to improving EoL care; implementation of system supports that increased knowledge, enhanced attitudes, and modelled appropriate behaviours (communication, knowledge, and attitudes) | Usual palliative care |

| Education of Informal Caregivers and Patients | |||

| Meyers et al, 2011 (17) | Patients and informal caregivers | Three conjoint in-person educational sessions that addressed a problem known to affect patients with cancer (including physical or psychological symptoms or issues related to resources or relationships) and communicating with the health care team (symptom management) | Usual palliative care |

| Bakitas et al, 2009 (18) | Patients | Educational approach to encourage patient activation, self-management, and empowerment (symptom management and coping skills) | Usual care participants were allowed to use all oncology and supportive services without restrictions, including referral to interdisciplinary palliative care service |

| McMillan et al, 2006 (19) | Informal caregivers | Problem-solving training and therapy (coping skills) | Usual hospice care |

Abbreviation: EoL, end of life.

Outcomes

Patient Quality of Life

Table 4 describes the findings of 5 studies that reported on patient quality of life. (14–18) Educating either health care providers or patients and informal caregivers did not lead to significant improvement in the quality of life of patients nearing EoL.

Table 4:

Patient Quality of Life

| Author, Year | Sample Size, N I/C | Quality of Life Scale | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Education of Health Care Providers | |||

| Pelayo-Alvarez et al, 2013 (14) | 63/54 | Rotterdam Symptom Checklist global scale | > 0.05 |

| Curtis et al, 2013 (15) | 771/946 | Quality of End-of-Life Care questionnaire | 0.34 |

| Curtis et al, 2011 (16) | 182/214 | Quality of Dying and Death questionnaire | 0.33 |

| Education of Patients and Informal Caregivers | |||

| Meyers et al, 2011 (17) | 324/117 | City of Hope quality-of-life instruments | 0.70 |

| Bakitas et al, 2009 (18) | 145/134 | Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy–Palliative Care | 0.15 |

Abbreviation: C, control; I, intervention.

Informal Caregiver Quality of Life

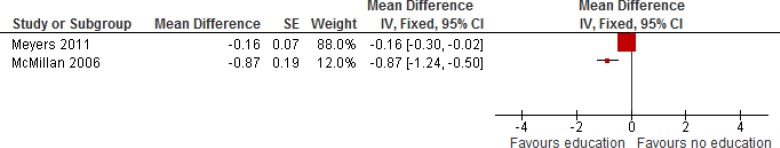

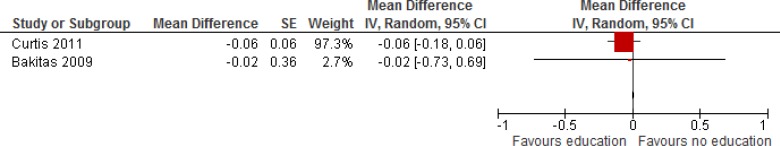

Table 5 describes the findings of 3 studies that looked at informal caregiver quality of life. (15;17;19) The study by Curtis et al (15) described educational intervention for health care providers and reported no significant difference in informal caregiver quality of life. The other 2 studies (17;19) described educational interventions for patients nearing EoL and their informal caregivers and reported a significant difference in informal caregiver quality of life. When 2 studies educating patients and caregivers were pooled in meta-analysis, there was improvement in informal caregiver quality of life (Figure 3).

Table 5:

Informal Caregiver Quality of Life

| Author, Year | Sample Size, N I/C | Quality of Life Scale | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Education of Health Care Providers | |||

| Curtis et al, 2013 (15) | 421/401 | Quality of End-of-Life Care questionnaire | 0.33 |

| Education of Patients and Informal Caregivers | |||

| Meyers et al, 2011 (17) | 324/117 | City of Hope quality-of-life instruments | 0.02 |

| McMillan et al, 2006 (19) | 111/109 | Caregiver Quality of Life Index–Cancer | 0.03 |

Abbreviation: C, control; I, intervention.

Figure 3: Informal Caregiver Quality of Life.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; df, degrees of freedom; I2, degree of heterogeneity; IV, instrumental variable; SE, standard error.

Patient Pain Control

Table 6 describes 2 studies that looked at patient pain control. (14;16) There was no significant improvement in pain control after educational interventions for health care providers.

Table 6:

Pain Control

| Author, Year | Sample Size, N I/C | Pain Control Scale | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pelayo-Alvarez et al, 2013 (14) | 63/54 | Brief Pain Inventory Palliative Care Outcome Scale | NS |

| Curtis et al, 2011 (16) | 165/144a | Chart abstraction | 0.81 |

Abbreviation: I, intervention; C, control; NS, not significant.

Measured as a secondary outcome in a smaller sample.

Patient Symptom Control

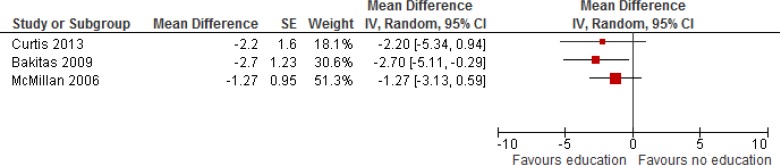

Table 7 describes 3 studies that reported on overall symptom management. Two reported a statistically significant improvement in symptom control among patients nearing EoL. (15;19) Meta-analysis showed overall improvement of symptoms in patients nearing EoL (Figure 4).

Table 7:

Symptom Control

| Author, Year | Sample Size, N I/C | Primary Symptom(s) | Symptom Scale | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Education of Health Care Providers | ||||

| Curtis et al, 2013 (15) | 771/946 | Depression | 8-item Personal Health Questionnaire | 0.006 |

| Education of Patients and Informal Caregivers | ||||

| Bakitas et al, 2009 (18) | 145/134a | All symptomsb | Edmonton Symptom Assessment Scale | 0.83 |

| McMillan et al, 2006 (19) | 111/109a | All symptoms | Memorial Symptom Assessment Scale | < 0.001 |

Abbreviation: I, intervention; C, control.

Measured as a secondary outcome in a smaller sample.

Except for constipation, dizziness, and pain, which were statistically significant.

Figure 4: Symptom Control.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; df, degrees of freedom; I2, degree of heterogeneity; IV, instrumental variable; SE, standard error.

Informal Caregiver and Health Care Provider Satisfaction

Table 8 describes 2 studies that reported on informal caregiver and health care provider satisfaction. (14;16) Neither caregiver nor health care provider satisfaction significantly differed after an educational intervention for health care providers.

Table 8:

Informal Caregiver and Health Care Provider Satisfaction

| Author, Year | Sample Size, N I/C | Satisfaction Scale | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Caregiver Satisfaction | |||

| Pelayo-Alvarez et al, 2013 (14) | 48/36a | Spanish version of SERVQUAL | NS |

| Curtis et al, 2011 (16) | 182/214 | Quality of Dying and Death questionnaire | 0.66 |

| Health Care Provider Satisfaction | |||

| Curtis et al, 2011 (16) | 71/106a | Quality of Dying and Death questionnaire | 0.81 |

Abbreviation: I, intervention; C, control; NS, not significant.

Measured as a secondary outcome in a smaller sample.

Number of Hospital Days and Emergency Department Visits

Table 9 describes the findings of 1 study (18) that reported on number of hospital days and emergency department visits. There was no significant difference after an educational intervention for patients.

Table 9:

Number of Hospital Days and Emergency Department Visits

| Author, Year | Sample Size, N I/C | Outcome | Mean, N I/C | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bakitas et al, 2009 (18) | 145/134 | Hospital days | 2.6/2.8a | 0.60 |

| ED visits | 0.28/0.38a | 0.62 |

Abbreviation: C, control; ED, emergency department; I, intervention; NR, not reported; SD, standard deviation.

Confidence interval not reported.

Intensive Care Unit Admissions

Table 10 describes the findings of 2 studies that reported on intensive care unit admissions. There was no significant difference in admissions after an educational intervention for health care providers. (16;18) Meta-analysis showed no significant difference when results were pooled (Figure 5).

Table 10:

Intensive Care Unit Admissions

| Author, Year | Sample Size, N I/C | Parameter Estimate (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Curtis et al, 2011 (16) | 182/214 | Number of days in the ICU HR 0.86 (0.73–1.01) | 0.07 |

| Bakitas et al, 2009 (18) | 145/134 | Mean number of ICU admissions 0.03 intervention/0.05 control (NR) | 0.36 |

Abbreviation: C, control; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; I, intervention; ICU, intensive care unit.

Figure 5: Intensive Care Unit Admissions.

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; df, degrees of freedom; I2, degree of heterogeneity; IV, instrumental variable; SE, standard error.

Conclusions

Educational interventions for health care providers that were focused on improving communication skills, knowledge, and attitudes towards EoL care:

significantly improved patient symptom control (moderate quality evidence) but did not significantly improve pain control (moderate quality evidence)

did not significantly improve informal caregiver quality of life, informal caregiver satisfaction, or health care provider satisfaction (moderate quality evidence)

did not improve resource utilization, including number of hospital days, emergency department visits, or intensive care unit admissions (moderate quality evidence)

did not significantly improve patient quality of life (low quality evidence)

Educational interventions for informal caregivers and patients that were focused on symptom management and coping skills:

significantly improved informal caregiver quality of life (moderate quality evidence)

significantly improved patient symptom control (moderate quality evidence)

did not improve resource utilization, including number of hospital days, emergency department visits, or number of intensive care unit admissions (moderate quality evidence)

did not significantly improve patient quality of life (low quality evidence)

Acknowledgements

Editorial Staff

Jeanne McKane, CPE, ELS(D)

Medical Information Services

Corinne Holubowich, BEd, MLIS

Health Quality Ontario's Expert Advisory Panel on End-of-Life Care

| Panel Member | Affiliation(s) | Appointment(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Panel Co-Chairs | ||

| Dr Robert Fowler | Sunnybrook Research Institute University of Toronto | Senior Scientist Associate Professor |

| Shirlee Sharkey | St. Elizabeth Health Care Centre | President and CEO |

| Professional Organizations Representation | ||

| Dr Scott Wooder | Ontario Medical Association | President |

| Health Care System Representation | ||

| Dr Douglas Manuel | Ottawa Hospital Research Institute University of Ottawa | Senior Scientist Associate Professor |

| Primary/Palliative Care | ||

| Dr Russell Goldman | Mount Sinai Hospital, Tammy Latner Centre for Palliative Care | Director |

| Dr Sandy Buchman | Mount Sinai Hospital, Tammy Latner Centre for Palliative Care Cancer Care Ontario University of Toronto | Educational Lead Clinical Lead QI Assistant Professor |

| Dr Mary Anne Huggins | Mississauga Halton Palliative Care Network; Dorothy Ley Hospice | Medical Director |

| Dr Cathy Faulds | London Family Health Team | Lead Physician |

| Dr José Pereira | The Ottawa Hospital University of Ottawa | Professor, and Chief of the Palliative Care program at The Ottawa Hospital |

| Dean Walters | Central East Community Care Access Centre | Nurse Practitioner |

| Critical Care | ||

| Dr Daren Heyland | Clinical Evaluation Research Unit Kingston General Hospital | Scientific Director |

| Oncology | ||

| Dr Craig Earle | Ontario Institute for Cancer Research Cancer Care Ontario | Director of Health Services Research Program |

| Internal Medicine | ||

| Dr John You | McMaster University | Associate Professor |

| Geriatrics | ||

| Dr Daphna Grossman | Baycrest Health Sciences | Deputy Head Palliative Care |

| Social Work | ||

| Mary-Lou Kelley | School of Social Work and Northern Ontario School of Medicine Lakehead University | Professor |

| Emergency Medicine | ||

| Dr Barry McLellan | Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | President and Chief Executive Officer |

| Bioethics | ||

| Robert Sibbald | London Health Sciences Centre University of Western Ontario | Professor |

| Nursing | ||

| Vicki Lejambe | Saint Elizabeth Health Care | Advanced Practice Consultant |

| Tracey DasGupta | Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre | Director, Interprofessional Practice |

| Mary Jane Esplen | De Souza Institute University of Toronto | Director Clinician Scientist |

Appendices

Appendix 1: Literature Search Strategies

Databases searched: EBM Reviews - Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews <2005 to October 2013>, EBM Reviews - ACP Journal Club <1991 to November 2013>, EBM Reviews - Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects <4th Quarter 2013>, EBM Reviews - Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials <October 2013>, EBM Reviews - Cochrane Methodology Register <3rd Quarter 2012>, EBM Reviews - Health Technology Assessment <4th Quarter 2013>, EBM Reviews - NHS Economic Evaluation Database <4th Quarter 2013>, Embase <1980 to 2013 Week 47>, Ovid MEDLINE(R) <1946 to November Week 3 2013>, Ovid MEDLINE(R) In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations <November 27, 2013>

Search Strategy

| # | Searches | Results |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | exp Terminal Care/ | 86915 |

| 2 | exp Palliative Care/ use mesz,acp,cctr,coch,clcmr,dare,clhta,cleed or exp Terminally Ill/ use mesz,acp,cctr,coch,clcmr,dare,clhta,cleed | 45676 |

| 3 | exp palliative therapy/ use emez or exp terminally ill patient/ use emez or exp terminal disease/ use emez or exp dying/ use emez | 73127 |

| 4 | ((End adj2 life adj2 care) or EOL care or (terminal* adj2 (care or caring or ill* or disease*)) or palliat* or dying or (Advanced adj3 (disease* or illness*)) or end stage*).ti,ab. | 340496 |

| 5 | or/1–4 | 434706 |

| 6 | exp *Education/ | 848145 |

| 7 | (educat* or curricul* or classroom* or train* or learn* or teach*).ti,ab. | 2018594 |

| 8 | or/6–7 | 2417444 |

| 9 | 5 and 8 | 29080 |

| 10 | exp “Quality of Life”/ | 386073 |

| 11 | exp Patient Readmission/ use mesz,acp,cctr,coch,clcmr,dare,clhta,cleed | 8614 |

| 12 | exp hospital readmission/ use emez | 15144 |

| 13 | (quality of life or QOL or emergency room visit* or hospital readmission*).ti,ab. | 390236 |

| 14 | or/10–13 | 547409 |

| 15 | 9 and 14 | 3417 |

| 16 | limit 15 to english language [Limit not valid in CDSR,ACP Journal Club,DARE,CCTR,CLCMR; records were retained] | 3138 |

| 17 | limit 16 to yr=“2003 -Current” [Limit not valid in DARE; records were retained] | 2345 |

| 18 | remove duplicates from 17 | 1607 |

CINAHL

| # | Query | Results |

|---|---|---|

| S1 | (MH “Terminal Care+”) | 39,250 |

| S2 | (MH “Palliative Care”) | 19,910 |

| S3 | (MH “Terminally Ill Patients+”) | 7,716 |

| S4 | ((End N2 life N2 care) or EOL care or (terminal* N2 (care or caring or ill* or disease*)) or palliat* or dying or (advanced N3 (disease* or illness*)) or end stage*) | 52,768 |

| S5 | S1 OR S2 OR S3 OR S4 | 60,774 |

| S6 | (MM “Education+”) | 264,924 |

| S7 | (educat* or curricul* or classroom* or train* or learn* or teach*) | 583,322 |

| S8 | S6 OR S7 | 645,534 |

| S9 | S5 AND S8 | 10,187 |

| S10 | (MH “Quality of Life+”) | 57,754 |

| S11 | (MH “Readmission”) | 4,769 |

| S12 | (quality of life or QOL or emergency room visit* or hospital readmission*) | 77,877 |

| S13 | S10 OR S11 OR S12 | 84,483 |

| S14 | S9 AND S13 | 1,138 |

| S15 | S9 AND S13 Limiters - Published Date: 20030101–20131231; English Language | 861 |

Appendix 2: Evidence Quality Assessment

Table A1:

GRADE Evidence Profile for the Comparison of Educational Intervention and Usual Care

| Number of Studies (Design) | Risk of Bias | Inconsistency | Indirectness | Imprecision | Publication Bias | Upgrade Considerations | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient Quality of Life | |||||||

| 5 (RCTs) (14–18) | Serious limitations (−1)a | Serious limitations (−1)b | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | None | ⊕⊕ Low |

| Informal Caregiver Quality of Life | |||||||

| 3 (RCTs) (15;17;19) | Serious limitations (−1)a | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | None | ⊕⊕⊕ Moderate |

| Patient Pain Control | |||||||

| 2 (RCTs) (14;16) | Serious limitations (−1)a | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | None | ⊕⊕⊕ Moderate |

| Patient Symptom Control | |||||||

| 3 (RCTs) (15;18;19) | Serious limitations (−1)a | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | None | ⊕⊕⊕ Moderate |

| Informal Caregiver Satisfaction | |||||||

| 2 (RCTs) (14;16) | Serious limitations (−1)a | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | None | ⊕⊕⊕ Moderate |

| Health Care Provider Satisfaction | |||||||

| 1 (RCT) (16) | Serious limitations (−1)a | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | None | ⊕⊕⊕ Moderate |

| Number of Hospital Days | |||||||

| 1 (RCT) (18) | Serious limitations (−1)a | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | None | ⊕⊕⊕ Moderate |

| Number of Emergency Department Visits | |||||||

| 1 (RCT) (18) | Serious limitations (−1)a | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | None | ⊕⊕⊕ Moderate |

| Intensive Care Unit Admissions | |||||||

| 2 (RCTs) (16;18) | Serious limitations (−1)a | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | No serious limitations | Undetected | None | ⊕⊕⊕ Moderate |

Abbreviations: GRADE, Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation; RCT, randomized controlled trial.

Concealment and blinding were unclear.

Results were inconsistent among the different studies.

Table A2:

Risk of Bias Among Randomized Controlled Trials for the Comparison of Educational Intervention and Usual Care

| Author, Year | Allocation Concealment | Blinding | Complete Accounting of Patients and Outcome Events | Selective Reporting Bias | Other Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pelayo-Alvarez et al, 2013 (14) | No limitations | Limitationsa | No limitations | No limitations | No limitations |

| Curtis et al, 2013 (15) | Limitationsb | No limitations | No limitations | No limitations | Limitationsc |

| Curtis et al, 2011 (16) | Limitationsb | Limitationsd | No limitations | No limitations | Limitationsc |

| Meyers et al, 2011 (17) | Limitationsb | Limitationsa | No limitations | No limitations | No limitations |

| Bakitas et al, 2009 (18) | Limitationsb | Limitationsa | No limitations | No limitations | No limitations |

| McMillan et al, 2005 (19) | Limitationsb | Limitationsa | No limitations | No limitations | No limitations |

Blinding unclear.

Concealment unclear.

Potential for non-response/response bias.

No blinding.

References

- (1).Van MW, Aertgeerts B, De CK, Thoonsen B, Vermandere M, Warmenhoven F, et al. Defining the palliative care patient: a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2013; 27(3): 197–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Stewart AL, Teno J, Patrick DL, Lynn J. The concept of quality of life of dying persons in the context of health care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999; 17(2): 93–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Report of the 1990 joint committee on health education terminology. J Sch Health. 1991;61 (6): 251–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Green LW, Kreuter MW. Health promotion planning: an educational and ecological approach. 3rd ed. Mountain View (CA): Mayfield Publishing Company; 1999. 621 p. [Google Scholar]

- (5).Review Manager (RevMan) [computer program]. Version 5.0. Copenhagen: The Nordic Cochrane Centre, The Cochrane Collaboration; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- (6).DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986; 7(3): 177–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Laird NM, Mosteller F. Some statistical methods for combining experimental results. Int J Technol Assess Health Care. 1990; 6(1): 5–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).van Houwelingen HC, Arends LR, Stijnen T. Advanced methods in meta-analysis: multivariate approach and meta-regression. Stat Med. 2002; 21(4): 589–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002; 21(11): 1539–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Song F, Khan KS, Dinnes J, Sutton AJ. Asymmetric funnel plots and publication bias in meta-analyses of diagnostic accuracy. Int J Epidemiol. 2002; 31(1): 88–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).von EE, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gotzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. PLoS Med. 2007; 4(10): e296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Guyatt GH, Oxman AD, Schunemann HJ, Tugwell P, Knottnerus A. GRADE guidelines: a new series of articles in the Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011; 64(4): 380–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Goodman C. Literature searching and evidence interpretation for assessing health care practices. Stockholm, Sweden: Swedish Council on Technology Assessment in Health Care; 1996. 81 p. SBU Report No. 119E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Pelayo-Alvarez M, Perez-Hoyos S, Agra-Varela Y. Clinical effectiveness of online training in palliative care of primary care physicians. J Palliat Med. 2013; 16(10): 1188–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Curtis JR, Back AL, Ford DW, Downey L, Shannon SE, Doorenbos AZ, et al. Effect of communication skills training for residents and nurse practitioners on quality of communication with patients with serious illness: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2013; 310(21): 2271–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Curtis JR, Nielsen EL, Treece PD, Downey L, Dotolo D, Shannon SE, et al. Effect of a quality-improvement intervention on end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: a randomized trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011; 183(3): 348–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Meyers F, Carducci M, Loscalzo M, Linder J, Greasby T, Beckett L. Effects of a problem-solving intervention (COPE) on quality of life for patients with advanced cancer on clinical trials and their caregivers: Simultaneous Care Educational Intervention (SCEI): linking palliation and clinical trials. J Palliat Med. 2011; 14(4): 465–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Bakitas M, Lyons KD, Hegel MT, Balan S, Brokaw FC, Seville J, et al. Effects of a palliative care intervention on clinical outcomes in patients with advanced cancer: The project ENABLE II randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009; 302(7): 741–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).McMillan SC, Small BJ, Weitzner M, Schonwetter R, Tittle M, Moody L, et al. Impact of coping skills intervention with family caregivers of hospice patients with cancer: a randomized clinical trial. Cancer. 2006; 106(1): 214–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]