Abstract

Temperature-triggered phase separation of recombinant proteins has offered substantial opportunities in the design of nanoparticles for a variety of applications. Herein we describe the temperature-triggered phase separation behavior of a recombinant hydrophilic resilin-like polypeptide (RLP). The transition temperature and sizes of RLP-based nanoparticles can be modulated based on variations in polypeptide concentration, salt identity, ionic strength, pH, and denaturing agents, as indicated via UV-Vis spectroscopy and dynamic light scattering (DLS). The irreversible particle formation is coupled with secondary conformational changes from a random coil conformation to a more ordered β-sheet structure. These RLP-based nanoparticles could find potential use as mechanically-responsive components in drug delivery, nanospring, nanotransducer, and biosensor applications.

Keywords: Hofmeister series, nanoparticle, phase transition, protein aggregation, resilin-like polypeptide

1. Introduction

Proteins that respond to biologically relevant factors by altering their conformation or mechanical properties have emerged as a class of intelligent biomaterials for drug delivery and regenerative medicine.[1-4] In particular, polypeptides based on elastin and its derivatives, which comprise the repetitive consensus sequence of tropoelastin (the VPGVG pentapeptide), show an inverse transition temperature at which the polypeptides aggregate to form a dense coacervate.[5-7] This transition is reversible and the transition temperature can be modulated via changing hydrophobicity, polypeptide length, protein concentration, molecular architecture, temperature, salt, ionic strength and pH; this versatility has permitted the engineering and targeting of desired bio-functions for biomedical applications.[5, 8-11]

The coacervation of elastin and its derivatives share commonalities with other protein aggregation events. Secondary conformations play a critical role in protein aggregation, with most aggregation events accompanied by structural rearrangements that stabilize the β-sheet conformation.[12] The coacervates of elastin-like polypeptides (ELPs) are likewise usually associated with conformational changes that include an increased β-sheet content, common to other protein aggregates that form amyloid protein fibrils consisting of misfolded cross-β sheet structures.[12, 13] Given that the nuances of protein aggregation can potentially interfere with the targeted properties of a protein, understanding and controlling the aggregation or phase separation of polypeptides hold significant implications in protein engineering applications.[12, 14,15]

Among all the external factors, modulating the temperature of a protein solution is the most common strategy for inducing protein aggregation. Increasing temperature enhances hydrophobic interactions, increases diffusion of proteins, and boosts the frequency of intermolecular collisions, leading to accelerated formation of aggregates.[16] Other factors are commonly employed as well, for example pH can also impact the rate of protein aggregation owing to changes in the surface charges on proteins, which not only affect intramolecular folding interactions but also intermolecular protein-protein interactions. Similar to pH, ionic strength is another key solution condition to potentially modulate protein association/aggregation.[17, 18] Both positive and negative ions are able to interact electrostatically with proteins, leading to altered charge-charge interactions and transformed secondary conformational states which may result in variations in aggregation behavior.[14, 15]

A variety of proteins are subject to this conformational and coacervation behavior. Resilin, an elastomeric insect structural protein found in the specialized compartments of most arthropods, has been recognized for its outstanding mechanical elasticity that is shown to participate heavily in insects' daily activities such as jumping fleas, flying dragonflies and producing sound cicadas.[19, 20] Recently, recombinant resilin-like polypeptides (RLPs) have gained tremendous attention as potential biomaterial substitutes for a variety of mechanically demanding tissue engineering applications, as the polypeptides capture the mechanical properties of the native protein.[20-28] Although there has been significant focus on the outstanding mechanical properties of emerging RLPs, there have been limited reports detailing the interesting thermal behavior of this novel elastomeric protein.[29-31] Rec1-resilin, which comprises the sequence derived from the first exon of the Drosophila melanogaster gene, has shown pH-and temperature-responsive behavior, exhibiting dual phase-transition behavior characterized by both lower (LCST) and upper critical solution temperatures (UCST).[32, 33]

Here we characterize the nanoparticle formation and investigate the temperature triggered phase-transition behavior of a novel resilin-like polypeptide containing 12-repeats of a modified 15-amino-acid consensus motif from the D. melanogaster CG15920 gene (in which tyrosines (Y) were replaced with phenylalanine (F) and methionine (M) to provide options for future chemical modification),[20, 34] which comprises a high content of hydrophilic and charged amino acids.[21, 23, 34, 35] UV-Vis spectroscopy and DLS were employed to characterize phase transition temperatures and nanoparticle size based upon the use of various salts, ionic strength, pH and denaturing agents. The irreversible particle formation process is coupled with heat-associated secondary conformational changes characterized via CD and FTIR and the morphology of the nanoparticles was characterized via TEM.

2. Results and Discussion

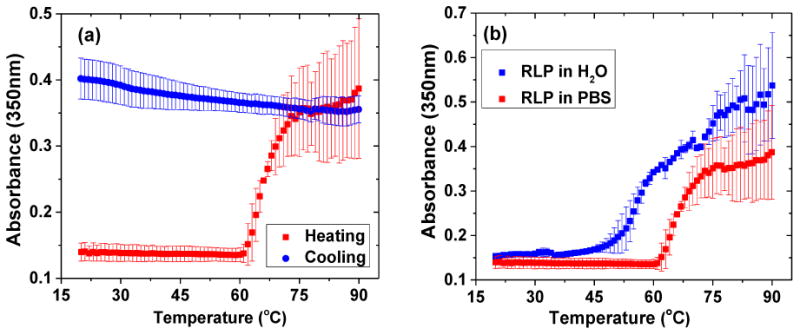

The phase transition temperature for this protein was quantified by monitoring the absorbance of RLP solutions in filtered solvent at 350nm as a function of temperature (Figure 1 and Figure S1a). The absorbance for the RLP in PBS displays a transition at 64°C (determined as the inflection in the absorbance spectrum), indicating the aggregation of the RLP. Interestingly, this phase transition is irreversible and the polypeptide remains in an aggregated state even after cooling to 20°C (Figure 1a). The transition temperature is also concentration dependent, and with an increase in RLP concentration (to 16mg/mL), the transition temperature decreases to 58°C (Figure S1b). The RLP exhibited a lower transition temperature in DI water compared to PBS (Figure 1b), which is likely due to the association of the salt anions in PBS with the charged residues of the RLP facilitating the overall protein solubility. In pure water, without the ion paring effect, the RLP becomes less soluble and phase separates at a lower temperature.

Figure 1. Turbidity measurements for RLP solutions as a function of temperature.

Turbidity profiles were obtained by monitoring optical density via UV-Vis at 350nm as the solution was heated at a constant rate of 1°C/min from 20°C to 90°C. (a) Turbidity profile of heating and cooling at 8mg/mL RLP solution at pH 7.4 in PBS; (b) turbidity profile of 8mg/mL RLP in DI water and PBS. Error bars represent the standard deviation of a minimum of three replicates.

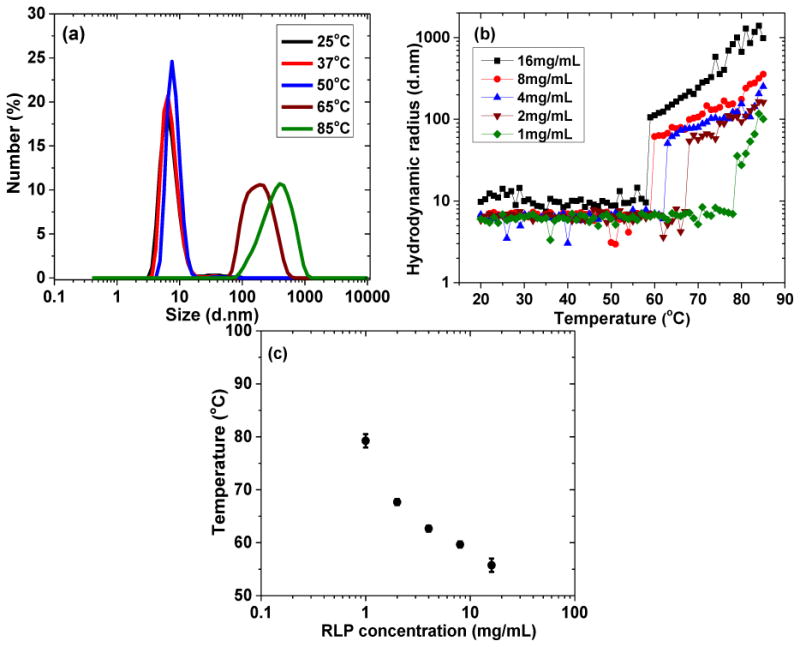

The temperature-dependent phase transition behavior was further confirmed via DLS by monitoring the change of particle size in PBS over a range of temperatures. A drastic increase in diameter (shown in Figure 2a), from roughly 8nm to over 100nm, occurs once the temperature reaches 65°C, confirming the formation of nanoparticles. RLP-based nanoparticles continue to increase in size with the increase of temperature from 65°C to 80°C (Figure S3). Figure 2b illustrates that the hydrodynamic radius of the nanoparticles increases with RLP concentration between 1mg/mL to 16mg/mL. The transition temperatures for solutions with various RLP concentrations (taken at the point at which the hydrodynamic radius shows a drastic increase) are summarized in Figure 2c, with an increase of protein concentration correlating with a lower transition temperature. This characteristic concentration dependence is consistent with that observed for elastin-like (ELPs) and silk-like polypeptides (SLPs) yet in contrast to those of vinyl polymers (e.g. pNIPAM) whose thermoresponsiveness is generally independent of polymer concentration because of the dehydration-associated hydrophobic collapse.[36-39]

Figure 2. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) measurements of transition temperatures of RLPs at pH 7.4 in PBS at various polypeptide concentrations.

(a) Percentage of number average of 8mg/mL RLP solution incubated for 2 minutes at 5 distinct temperatures; (b) hydrodynamic radius measurements of RLP solutions at various protein concentrations heated at a constant rate of 1 °C/min from 20°C to 85°C; (c) summary of transition temperatures of RLP solutions at various protein concentrations. Error bars represent the standard deviation of a minimum of three replicates.

Temperature-independent, post-formulation stability of protein-based materials and drugs hold significant importance in drug delivery applications. In order to probe the stability of the RLP nanoparticles, the hydrodynamic radius of the particles was monitored via DLS upon cooling. The turbidity of heated RLP solutions was measured via UV-Vis at multiple time-points for a month after heating. The particle size remains constant during cooling process (Figure S4a) and the absorbance at both 25°C and 37°C (Figure S4b) remains high, suggesting the stability of particles for short (an hour) and long (at least a month) timescales. This stability was independent of the presence of various salts, changes in ionic strength, and pH (see below).

Although conducted at significantly lower concentrations than the DLS and UV-Vis experiments, circular dichroic spectroscopy (CD) provided a simple method for monitoring conformational transitions of the RLP. In general, the CD spectra exhibited a strong minimum near 195nm indicative of random coil conformation and a minor positive feature near 213nm indicative of β-turn structure (Figure S5a). With an increase in temperature to 80°C, the negative minimum at 195nm progressively decreased in intensity, with the concomitant appearance of a negative peak suggested at ca. 220nm, suggesting the conformational change from a random coil to β-sheet (Figure S5a). Given the low concentrations required for CD spectroscopy, FTIR spectroscopy was also employed to investigate the conformation of the RLP solutions and nanoparticles in D2O before and after heating, respectively (Figure S5b). The spectrum of the unheated RLP solution shows a main Amide I peak centered at 1640cm-1, indicative of random coil secondary structure. After heating to 85°C, the peak shifts to 1625cm-1, suggesting the formation of β-sheet structures. The change in the conformation of the RLP that occurs concomitant with aggregation shares similarities with other recombinant structural polypeptides such as ELP and SELP where the process of aggregation is coupled with secondary conformational changes (e.g., from random coil to β-turn and/or β-sheet).[13, 38, 40] The behavior of the polypeptides is in marked contrast to the LCST-driven aggregation of thermoresponsive vinyl polymers which occur via dehydration of the amide groups and hydrophobic collapse without the formation of any specific secondary or tertiary structures.[40-42]

In many clinical applications, proteins are mixed with not only water but also various co-solutes that may interfere with the aggregation process by binding to the proteins or substantially changing the surrounding water structure.[14, 15] As a result of these factors, the addition of Hofmeister anions (SO42->S2O32->F->Cl->Br->NO3->I->ClO4->SCN-) has been reported to impact the transition temperatures for a wide range of globular proteins, recombinant elastomeric polypeptides, as well as vinyl polymers.[43-46]

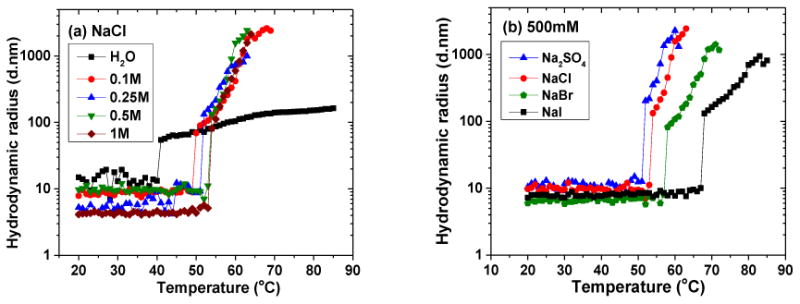

The impact of anions on the phase transition temperature of RLP was measured in the presence of different ionic strengths of NaCl (in water) and then also tested with several salts selected from the Hofmeister series at a given salt concentration. The hydrodynamic radius is plotted as a function of temperature in Figure 3a. RLPs under these ionic strengths exhibited a similar trend in particle size as that shown in Figure 2b, with a sharp increase in particle size at the phase transition temperature. The addition of NaCl to RLP in DI water resulted an increase in the phase transition temperature from 40°C (H20) to 50°C (100mM), which plateaued at 54°C for a solution containing 500mM NaCl. This is in stark contrast to what has been observed for different ELPs and other hydrophobic proteins or vinyl polymers in general, where the addition of NaCl causes a drastic decrease in phase transition temperature due to the disruption of surface hydrophobic hydration layers.[41, 42, 47] In addition, the data show a clear disparity in aggregation for RLPs in salt-containing versus water solutions, which is likely due to ion paring that occurs upon the addition of salts. The ion pairing shields charged residues and may thus affect both the electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions of the chain. These affects apparently induce, in solutions containing NaCl, additional and more rapid aggregation after the initial transition than in water. Figure 3b summarizes the hydrodynamic radius as a function of temperature in the presence of other Hofmeister salts and shows that the phase transition temperature of the RLP solution is altered depending on the identity of the salt, consistent with the expected behavior of the Hofmeister series at these high salt concentrations. (e.g., SO42- decreases the transition temperature while ions such as Br- and I- increase the transition temperature). The fact that the solubility of the RLP initially increases upon the addition of salt, but at high salt concentrations (>500mM) follows the Hofmeister series, suggests a two-step interaction in which an initial solubilizing interaction of ions with the charged moieties on the RLP is followed by protein/water interfacial depletion modulated by the identity of the ion. While these observations are in contrast to non-ionic polymers and ELPs, they are consistent with those reported for ELPs containing carboxylate side residues.[42, 43, 48, 49]

Figure 3. Hydrodynamic radius profiles of RLP solutions as a function of temperature under different buffer conditions.

All solutions were analyzed at RLP concentrations of 8 mg/mL and heated at 1°C/min from 20°C to 85°C. (a) RLP solution with NaCl concentrations at 0, 0.1, 0.25, 0.5 to 1M; (b) RLP at 500mM concentration of various salts.

The phase transition behavior of the RLP is also sensitive to pH, with RLP solutions at pH 5 displaying the lowest transition temperature (40°C) compared to those of RLP solutions at pH 7.4 (60°C) or pH 10 (65°C)(Figure S6). This phenomenon is consistent with the isoelectric point of the RLP (pI=5.2) as indicated via isoelectric focusing gel electrophoresis (Figure S7) and consistent with the reported pI of Rec1-resilin (pI=4.8).[32] The discrepancy between the experimentally determined pI and theoretically predicted pI (∼10.5) is likely due to the conformational complexity of RLP in solution where the proximity of the charged groups alters their pKa.

Denaturants such as urea or SDS are routinely used to modulate the phase transition behavior of proteins/polypeptides,[50] and were employed with RLP solutions (Figure S8). The RLP phase transition is sensitive to the addition of urea (Figure S8a), with an increase in urea concentration (0.25M to 1M) causing an increase in the transition temperature from 55°C to 70°C, suggesting a role of hydrogen bonding in the aggregation process.[51-53] The addition of 0.1M SDS (Figure S8a) results an apparent disappearance of the phase transition even at temperatures of up to 85°C, clearly indicating hydrophobic interactions as a key driving force for RLP aggregation and nanoparticle formation. Furthermore, pre-formed RLP nanoparticles can be completely resolubilized by treatment with 100mM SDS, although not by treatment with even high concentrations of urea (1M)(Figure S8b). These general observations are consistent with, although more pronounced than, trends observed for ELPs.[40, 50, 54]

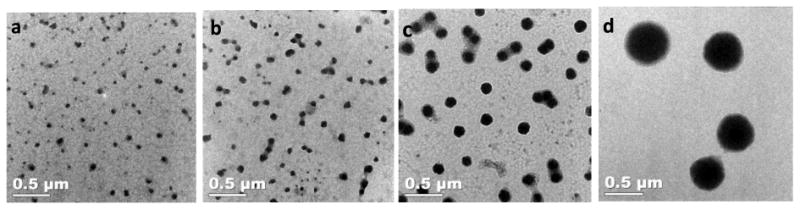

Characterization of the RLP nanoparticles via TEM at various temperatures shows that the nanoparticles are uniform, with sizes ranging from 20-30nm in diameter (below the transition temperature, Figure 4a and 4b) to 135±15nm (65°C)(Figure 4c) to 370±55nm (85°C)(Figure 4d), mainly consistent with the DLS analysis. This thermally driven evolution of RLP particle size increment is consistent with what has been observed for Rec1-resilin and diblock ELP-based micelles that show a second step of aggregation at higher temperatures.[32, 55]

Figure 4. Representative TEM images of RLP-based nanoparticles formed at various temperatures.

Images were taken for 8mg/mL solutions of RLP (stained with PTA (phosphotungstic acid)), after incubation at (a) 25°C (b) 50°C, (c) 65°C, and (d) 85°C.

3. Conclusions

The sensitivity of RLP aggregation into nanoparticles upon heating and the responsiveness of the transition to solution conditions such as salt identity, ionic strength, pH and denaturant, suggests that the thermally-induced aggregation is coupled with protein conformational changes, which are suggested to be to β-sheet containing structures based on the CD and FTIR data. The conformational rearrangement together with protein dehydration leads to hydrophobic-hydrophobic association, which eventually facilitates protein aggregation into insoluble clusters and nanoparticle formation. Despite the similarities of the temperature-induced aggregation of this RLP to the behavior observed for rec1-resilin, the transition was not as reversible as that for rec1-resilin and the UCST-type behavior observed for rec1-resilin was not observed for the RLP reported here, likely owing to the greater hydrophobicity of the rec1-resilin compared to the RLP. In addition, the increased solubility observed for the RLPs upon the addition of salt is opposite to observed trends in most ELPs, owing to the presence of ionized amino acid residues in our reported RLP.

The differences in the phase transition behaviors between these RLPs and that of ELPs illustrates potential opportunities for engineering polypeptide aggregation phenomenon via systematic modification of protein sequences. Specific ion pairing mechanisms may have important biotechnological implications for the design of thermostable proteins by the construction of ion-pairing sites on the surface of engineered proteins. The unique thermal responsiveness could enable the RLP to function as a stimuli-responsive biomaterial as well as to form controlled and uniform nanoparticles with potential application in drug delivery and biosensors. The composition of these RLPs could also offer significant versatility for engineering the phase transition behavior by tuning the charge distribution on the polypeptide, the percentage of hydrophobic residues, as well as the identity of the salt employed.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was funded by the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institute of Health [P20-RR017716 (K.L.K.)] and the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD RO1 DC011377A to K.L.K).

Footnotes

Supporting Information: Supporting Information is available from the Wiley Online Library or from the author.

Contributor Information

Linqing Li, University of Delaware, Department of Materials Science and Engineering, Newark, Delaware, 19716, United States.

Tianzhi Luo, University of Delaware, Department of Materials Science and Engineering, Newark, Delaware, 19716, United States.

Prof. Kristi L. Kiick, Email: kiick@udel.edu, University of Delaware, Department of Materials Science and Engineering; Biomedical Engineering, Newark, Delaware, 19716, United States; Delaware Biotechnology Institute, Newark, Delaware, 19711, United States.

References

- 1.Sampathkumar K, Arulkumar S, Ramalingam M. J Biomed Nanotech. 2014;10:367. doi: 10.1166/jbn.2014.1778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Langer R, Tirrell DA. Nature. 2004;428:487. doi: 10.1038/nature02388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hubbell JA, Chilkoti A. Science. 2012;337:303. doi: 10.1126/science.1219657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Luo Q, Dong Z, Hou C, Liu J. Chem Commun. 2014;50:9997. doi: 10.1039/c4cc03143a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vrhovski B, Weiss AS. Eur J Biochem. 1998;258:1. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.1998.2580001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chilkoti A, Christensen T, MacKay JA. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2006;10:652. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daamen WF, Veerkamp JH, van Hest JCM, van Kuppevelt TH. Biomaterials. 2007;28:4378. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Partridge SM, Davis HF. Biochem J. 1955;61:21. doi: 10.1042/bj0610021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Urry DW, Urry KD, Szaflarski W, Nowicki M. Adv Drug Delivery Rev. 2010;62:1404. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gagner JE, Kim W, Chaikof EL. Acta Biomater. 2014;10:1542. doi: 10.1016/j.actbio.2013.10.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.MacEwan SR, Chilkoti A. J Controlled Release. 2014;190:314. doi: 10.1016/j.jconrel.2014.06.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rauscher S, Baud S, Miao M, Keeley FW, Pomes R. Structure. 2006;14:1667. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Le DHT, Hanamura R, Pham DH, Kato M, Tirrell DA, Okubo T, Sugawara-Narutaki A. Biomacromolecules. 2013;14:1028. doi: 10.1021/bm301887m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang W. Int J Pharm. 2005;289:1. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2004.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang W, Nema S, Teagarden D. Int J Pharm. 2010;390:89. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpharm.2010.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mackay JA, Chilkoti A. Int J Hyperthermia. 2008;24:483. doi: 10.1080/02656730802149570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Truong MY, Dutta NK, Choudhury NR, Kim M, Elvin CM, Hill AJ, Thierry B, Vasilev K. Biomaterials. 2010;31:4434. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2010.02.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Callahan DJ, Liu W, Li X, Dreher MR, Hassouneh W, Kim M, Marszalek P, Chilkoti A. Nano Lett. 2012;12:2165. doi: 10.1021/nl300630c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Weis-Fogh T. J Exp Biol. 1960:889. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Elvin CM, Carr AG, Huson MG, Maxwell JM, Pearson RD, Vuocolo T, Liyou NE, Wong DCC, Merritt DJ, Dixon NE. Nature. 2005;437:999. doi: 10.1038/nature04085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Charati MB, Ifkovits JL, Burdick JA, Linhardt JG, Kiick KL. Soft Matter. 2009;5:3412. doi: 10.1039/b910980c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lv S, Dudek DM, Cao Y, Balamurali MM, Gosline J, Li HB. Nature. 2010;465:69. doi: 10.1038/nature09024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li LQ, Teller S, Clifton RJ, Jia XQ, Kiick KL. Biomacromolecules. 2011;12:2302. doi: 10.1021/bm200373p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Renner JN, Cherry KM, Su RSC, Liu JC. Biomacromolecules. 2012;13:3678. doi: 10.1021/bm301129b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li LQ, Tong ZX, Jia XQ, Kiick KL. Soft Matter. 2013;9:665. doi: 10.1039/C2SM26812D. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McGann CL, Levenson EA, Kiick KL. Macromol Chem Phys. 2013;214:203. doi: 10.1002/macp.201200412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li L, Kiick KL. ACS Macro Lett. 2013;2:635. doi: 10.1021/mz4002194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Li L, Kiick K. Front Chem. 2014;2:21. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2014.00021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weis-Fogh T. J Mol Biol. 1961;3:520. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lyons RE, Lesieur E, Kim M, Wong DCC, Huson MG, Nairn KM, Brownlee AG, Pearson RD, Elvin CM. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2007;20:25. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzl050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kim M, Elvin C, Brownlee A, Lyons R. Protein Express Purif. 2007;52:230. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2006.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dutta NK, Truong MY, Mayavan S, Choudhury NR, Elvin CM, Kim M, Knott R, Nairn KM, Hill AJ. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2011;50:4428. doi: 10.1002/anie.201007920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lyons RE, Elvin CM, Taylor K, Lekieffre N, Ramshaw JAM. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2012;109:2947. doi: 10.1002/bit.24565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ardell DH, Andersen SO. Insect Biochem Mol Biol. 2001;31:965. doi: 10.1016/s0965-1748(01)00044-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bailey K, Weis-Fogh T. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1961;48:452. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(61)90043-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kubota K, Fujishige S, Ando I. J Phys Chem. 1990;94:5154. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ohta H, Ando I, Fujishige S, Kubota K. J Polym Sci Part B: Polym Phys. 1991;29:963. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Xia XX, Xu Q, Hu X, Qin G, Kaplan DL. Biomacromolecules. 2011;12:3844. doi: 10.1021/bm201165h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lu Q, Zhu H, Zhang C, Zhang F, Zhang B, Kaplan DL. Biomacromolecules. 2012;13:826. doi: 10.1021/bm201731e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Yamaoka T, Tamura T, Seto Y, Tada T, Kunugi S, Tirrell DA. Biomacromolecules. 2003;4:1680. doi: 10.1021/bm034120l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Zhang Y, Furyk S, Bergbreiter DE, Cremer PS. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:14505. doi: 10.1021/ja0546424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cho Y, Zhang Y, Christensen T, Sagle LB, Chilkoti A, Cremer PS. J Phys Chem B. 2008;112:13765. doi: 10.1021/jp8062977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rembert KB, Paterová J, Heyda J, Hilty C, Jungwirth P, Cremer PS. J Am Chem Soc. 2012;134:10039. doi: 10.1021/ja301297g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hofmeister F. Arch Exp Pathol Pharmakol. 1888:247. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kunz W, Henle J, Ninham BW. Curr Opin in Colloid Interface Sci. 2004;9:19. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang Y, Cremer PS. Curr Opin Chem Biol. 2006;10:658. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2006.09.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Reguera J, Urry DW, Parker TM, McPherson DT, Rodríguez-Cabello JC. Biomacromolecules. 2007;8:354. doi: 10.1021/bm060936l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kherb J, Flores SC, Cremer PS. J Phys Chem B. 2012;116:7389. doi: 10.1021/jp212243c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sedlák E, Stagg L, Wittung-Stafshede P. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2008;479:69. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2008.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Thapa A, Han W, Simons RH, Chilkoti A, Chi EY, López GP. Biopolymers. 2013;99:55. doi: 10.1002/bip.22137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fang Y, Qiang JC, Hu DD, Wang MZ, Cui YL. Colloid Polym Sci. 2001;279:14. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sagle LB, Zhang Y, Litosh VA, Chen X, Cho Y, Cremer PS. J Am Chem Soc. 2009;131:9304. doi: 10.1021/ja9016057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pinedo-Martín G, Castro E, Martín L, Alonso M, Rodríguez-Cabello JC. Langmuir. 2014;30:3432. doi: 10.1021/la500464v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Urry DW. Angew Chem Int Ed Engl. 1993;32:819. [Google Scholar]

- 55.MacEwan SR, Chilkoti A. Nano Lett. 2012;12:3322. doi: 10.1021/nl301529p. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.