Abstract

The vast majority of infants are born in poor countries, but most of our knowledge about infants and children has emerged from high-income countries. In 2003 Tomlinson and Swartz conducted a survey of articles on infancy between 1996 and 2001 from major international journals, reporting that a meagre 5% of articles emanated from parts of the world other than North America, Europe, or Australasia. In this article we conducted a similar review of articles on infancy published between 2002 and 2012 to assess whether the status of cross-national research has changed in the subsequent decade. Results indicate that, despite slight improvements in research output from the rest of world, only 2.3% of articles published in 11 years included data from low- and middle-income countries – where 90% of the world’s infants live. These discrepancies are still indicative of progress needed to bridge the 10/90 gap in infant mental health research. Cross-national collaboration is urgently required to ensure expansion of research production in low-resource settings

Introduction

Children survive, and (hopefully) thrive within particular social, economic, and cultural settings. Despite consensus about the significance of infancy and early childhood to survival, well-being, and later development (Bornstein, 2014), there is a dearth of evidence on the diverse experiences and conditions that promote or impede infant development in low and middle income countries (LMIC) (Tomlinson & Swartz, 2003). Physical and social exposures at every stage of life influence risk for disease across the life cycle (Ben-Shlomo & Kuh, 2002; Kieling et al., 2011). Poverty and deprivation, common in LMIC, have detrimental effects on infants and children, although the pathways by which poverty affects these outcomes are not fully understood. Context-related limitations continue to constrain our global and international understanding of infant and child development, such as a narrow participant database in research. The little knowledge we do possess from LMIC often comes from studies with small samples in single locales (S.P. Walker et al., 2007), impeding our ability to identify which domains of development are susceptible to which experiences. This restriction of range also limits our ability to understand the many idiosyncrasies of child development and caregiving (Bornstein et al., 2012).

Over 90% of the world’s infants are born in LMIC (Population Reference Bureau, 2013b). The so-called '10/90 gap' (Saxena, Paraje, Sharan, Karam, & Sadana, 2006), where only 10% of the worldwide spending on health research is directed towards the problems that primarily affect the poorest 90% of the world's population, is now well known, and a significant literature has emerged that examines authorship and research output for high-income countries (HIC) when compared to low- and middle-income countries (LMIC). This gap stunts the development of evidence-based health policies and practice in LMIC. In some fields the gap is even greater and has been termed the 5/95 gap (Mari et al., 2010). There have also been studies examining how up to 96% of research participants in studies in psychology journals are from rich countries (Arnett, 2008) or what Henrich and colleagues termed WEIRD participants (white, educated, industrialised, rich, democratic) (Henrich, Heine, & Norenzayan, 2010).

In a study of papers published on child and adolescent mental health between 2002 and 2011, Kieling and colleagues (Kieling & Rohde, 2012) found that just over 90% had an author from a high-income country, with only 1.19% and 0.33% from lower-middle and low-income countries. That analysis revealed 42 countries (where more than 76 million children and adolescents live) where there was not a single publication (Kieling & Rohde, 2012). The disproportionately high representation of authors from HIC slowly decreased over the study time period with a relative decrease in output from 93.03% in 2002 to 88.96% in 2011. Among LMIC, the countries with the highest representation were Turkey (1.64%; ranked 12th), China (1.53%; 14th), and Brazil (1.42%; 15th) (Kieling & Rohde, 2012).

In 2003 Tomlinson and Swartz (Tomlinson & Swartz, 2003) conducted a literature survey of articles on infancy between 1996 and 2001 from 12 major international infancy and developmental journals. They reported that 93% of articles surveyed were written from Europe or North America, highlighting the serious imbalance in the knowledge production about infancy between poor and rich countries. A meagre 5% of articles reported data from parts of the world other than North America, Europe, or Australasia. The question arises as to whether this pattern has been maintained more than a decade since. Using similar methodology, we conducted a review of articles from 10 of the same international journals (two of the original 12 journals no longer exist) published between 2002 and 2012 to assess whether the status of cross-national research on infancy has changed in the subsequent 10 years.

Method

Similar to the method used in by Tomlinson and Swartz in 2003 (Tomlinson & Swartz, 2003), we conducted a retrospective review of the same major international journals dealing with infant behaviour and development that were included in the 2003 review. We reviewed articles published in these journals from 2002 to the end of 2012, an 11-year period. Table 1 lists the 10 developmental journals consulted. (Two of the 12 journals included in Tomlinson and Swartz’s original review, namely Advances in Infancy Research and Annual Progress in Child Psychiatry and Child Development no longer exist.) A total of 10 journals were therefore included in the current search. We downloaded all abstracts from each journal across the 11 years and then hand searched whether there was a word beginning with infan- in the abstract – words such as infancy, infant, infanticide, and so on - all articles in which the word infant and cognate terms appeared. All articles were analysed to determine the population of the study participants (infants) about which the article was written, and the affiliation of the first author (i.e. from what part of the world the article was published). The categories North America (USA and Canada), Europe (Including the United Kingdom), Australasia (Australia and New Zealand), and rest of world (all other countries) were used. If first author affiliation could not be determined or if the population of participants could not be reliably determined, a separate category “Not stated” was used. If data were collected in a Rest of the World country as well as one of the other categories we created a category “Multiple Countries”. All theoretical papers were rated “not applicable” even if empirical research from a particular region was used as the basis for the argument.

TABLE 1.

Number and Proportion of Articles on Infancy from Rest of World, in Selected Journals, Psych INFO, 2002–2012/12

| Journal | Total Number of Articles |

First Author Based in Rest of World |

Data Collected in Rest of World |

Total Percentage of Articles with First Author Based in Rest of World |

Total Percentage of Articles with Data Collected in Rest of World |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1996–2001* | 2002–2012 | 1996–2001* | 2002–2012 | 1996–2001* | 2002–2012 | 1996–2012 | 1996 – 2012 | |

| British Journal of Developmental Psychology | 31 | 51 | 3% | 2 (4%) | 3% | 0 (0%) | 3 (4%) | 1 (1%) |

| Child Development | 149 | 192 | 3% | 8 (4%) | 3% | 9 (5%) | 11 (3%) | 13 (4%) |

| Developmental Psychology | 124 | 212 | 5% | 15 (7%) | 7% | 15 (7%) | 21 (6%) | 24 (7%) |

| Infancy | 60 | 307 | 0% | 7 (2%) | 0% | 8 (3%) | 7 (2%) | 8 (2%) |

| Infant Behavior and Development | 210 | 512 | 3% | 62 (12%) | 4% | 58 (11%) | 69 (10%) | 66 (9%) |

| Infant Mental Health Journal | 90 | 191 | 4% | 13 (7%) | 3% | 17 (9%) | 17 (6%) | 20 (7%) |

| Infant and Child Development | 22 | 101 | 14% | 8 (8%) | 14% | 7 (7%) | 11 (9%) | 10 (8%) |

| Journal of Pediatric Psychology | 28 | 43 | 4% | 3 (7%) | 0% | 4 (9%) | 4 (6%) | 4 (6%) |

| Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology | 20 | 30 | 10% | 2 (7%) | 10% | 1 (3%) | 4 (8%) | 3 (6%) |

| Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development | 18 | 20 | 0% | 0 (0%) | 0% | 3 (15%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (8%) |

| Totals | 764 | 1659 | 3.5% | 120 (7.2%) | 3.9% | 122 (7.4%) | 147 (6%) | 152 (6.2%) |

Results presented in Tomlinson & Swartz (2003) for articles from Rest of World in selected journals in PsychINFO, 1996–2001/11

Results

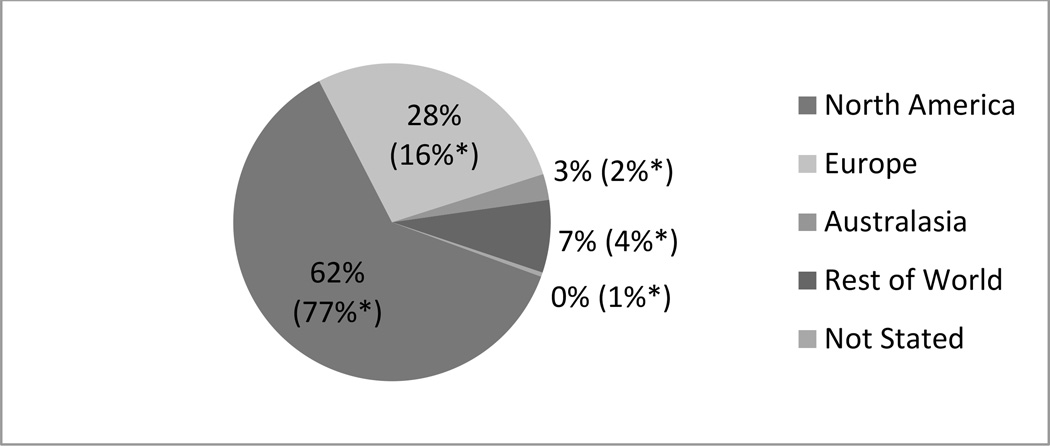

A total of 1659 articles were surveyed. As Figure 1 shows, the overwhelming majority of articles abstracted in the period selected were written from either North America (62%) or Europe (28%). The 3% contribution from Australasia by first author and as a region where data were collected is an overrepresentation by population, because only 0.54% of the world’s population lives in Australia and New Zealand (Population Reference Bureau, 2013a). Only 7% of first authors came from the rest of the world. The results obtained by Tomlinson and Swartz in 2003 are presented in parentheses in Figures 1 and 2. This result indicates a relative 15% decrease of articles by authors from North America since 2002; while the relative percentage of articles from Europe almost doubled from 16% to 28%. The percentage of first authors from the rest of the world increased 3%, showing a slight improvement in research output from these contexts.

FIGURE 1.

First author by affiliation by region

* Percentage in parentheses refers to results obtained by Tomlinson & Swartz (2003) for first author affiliation, by region 1996–2001/11 (n = 764)

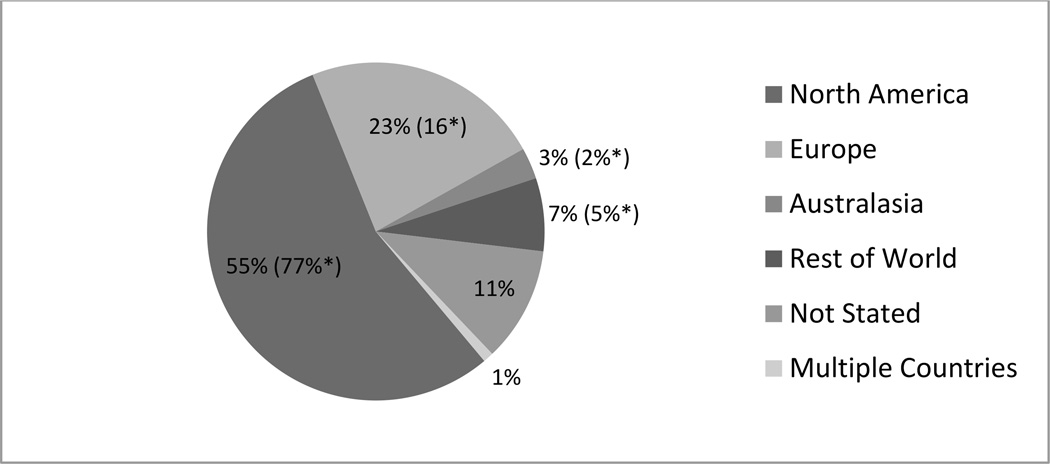

FIGURE 2.

Region in which data were collected

*Percentage in brackets refers to results obtained by Tomlinson & Swartz (2003) for region in which data was collected between 1996–2001/11 (n = 764).

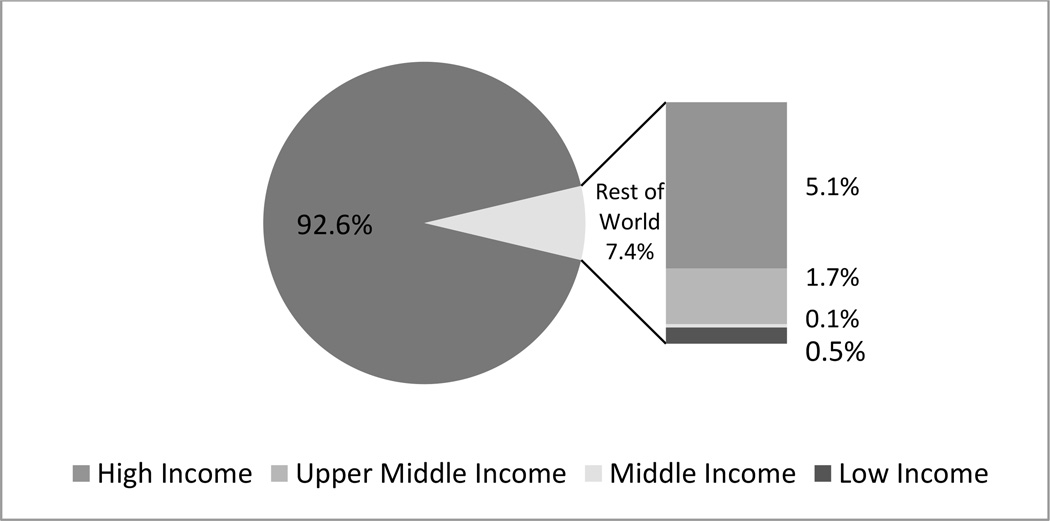

Results concerning region in which data were collected (Figure 2) resembles the region of origin of the author. Of the 1659 articles surveyed, only 7% of data were collected from the rest of the world. The percentage of articles presenting data collected in North America fell from 77% to 55%, but the 11% rise from Europe since 2002 mostly makes up for this relative decline. Similar to region of origin of the author, data collected from the rest of the world increased by 2%. Perhaps one of the most telling figures is that only 2.3% of articles (see Figure 3) published in 11 years included data from a LMIC – where 90% of the world’s infants live (Population Reference Bureau, 2013b).

Figure 3.

Regions making up the Rest of the World category

Just over 10% of articles were coded as country of data collection “not stated” - in these cases it was unclear in what region of the world the data were collected. A small percentage of articles (1%) where data collected had been collected in a HIC as well as a LMIC. The number and proportion of articles that came from the rest of the world for each journal are presented in Table 1. Over the period 2002–2012/121, the journal Infant Behavior and Development had both the highest number of articles on data collected from the rest of the world (n = 58) and the highest number of articles by authors based in the rest of the world (n = 62). This journal holds the highest percentage for articles in both categories; with nearly triple the percentage of articles of data collected in the rest of the world since 2002. Some journals showed significant increases in articles with data collected in the rest of the world such as Child Development (n = 9), Infancy (n = 8), and Infant Mental Health Journal (n = 17). All but three of the journals increased in the number or articles with data published from the rest of the world between 2002 and 2012/12. British Journal of Developmental Psychology (n = 0), Infant Child Development (n = 7) and Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology (n = 1) published relatively fewer articles since 2002. However, for some of the journals this observation is a function of a very low total of articles on infancy published in that journal over the period in question. Since 2002, the total number of articles on infancy more than doubled for first authors based in the rest of the world (7.2%) and nearly doubled for data collected in the rest of the world (7.4%).

Discussion

The vast majority of infants are born in poorer countries, but most of our knowledge about infants and children has emerged from richer countries. It is clear that, despite slight improvements in research output from LMIC, the imbalance of knowledge about infancy from rich and poor countries outlined by Tomlinson and Swartz in 2003 persists in the literature. A decade later, 82% of data for articles about infancy published in 10 prominent developmental journals were collected in North America, Europe, and Australasia. While at first blush this appears to be an improvement from the 92% of articles from HIC in the 2003 review, a careful reading of 10% of the manuscripts from the “Not stated” category suggests that most of the 11% from this category may in fact come from/represent North America, Europe, and Australasia. It is important to note that the relative output from the rest of the world has doubled, and while still below even the 10/90 gap it is encouraging that there has been an increase from underrepresented regions. Having said this, the imbalance remains alarming and it remains a significant problem that most of what we know about infants comes from research on white infants, of educated parents, living in rich industrialised democracies (Henrich et al., 2010). Understanding the imbalance is complex. A host of factors may play a part, such as the conditions of educational and research infrastructures in most LMIC (Tomlinson & Swartz, 2003) the English language preference of most international journals (Hamel, 2007), the sheer numbers of active researchers residing in North America, Europe, and Australasia.

Recent investments in mental health services research in LMIC are contributing to a change in the landscape. A growing body of evidence on the effectiveness of task-shifting interventions, scaling up of mental health service delivery, and integration into primary care in LMIC is becoming available (Lund et al., 2012; Tomlinson et al., 2011). Over the past decade, the potential for delivery of evidence-based packages of care for mental disorders has grown globally (Collins, Insel, Chockalingam, Daar, & Maddox, 2013). The potential is there, we now need to expand and establish the evidence-base from LMIC to identify the most promising interventions specifically for infant and child mental health. Klasen and Crombag (Klasen, 2013) state that, while it is tempting to translate evidence from HIC to LMIC, studies need to be replicated in specific contexts to establish their relevance for these settings. It is also important to consider context-specific limitations such as the scarcity of human resources and infrastructure and how these factors may affect knowledge production and research output. Increasing commitment to research output will not be useful without considering the feasibility and correctness of specific methodologies for different settings. Understanding how different research methodologies may contribute to our ability to produce knowledge about infancy that is more representative of the global picture remains an intriguing challenge for future research (Tomlinson & Swartz, 2003). An increase of evidence-based interventions for infant and child mental health from LMIC is emerging (Klasen, 2013), often using community health workers in areas where trained specialists are scarce (Cooper et al., 2002; Klein & Rye, 2004; S. P. Walker, Chang, Powell, Simonoff, & Grantham-McGregor, 2006). Continuing efforts to identify the most promising approaches and the most urgent research gaps in infant mental health will be valuable in fostering increased knowledge production from underrepresented regions of the globe.

Cross-national collaboration is urgently required to ensure expansion of research production in low-resource settings. Research partnerships that allow for meaningful participation and exchange of knowledge and methods can facilitate dissemination and uptake of innovations. Such multinational developmental inquiry, constructed within a sensitive contextual framework, will allow the developmental community to distinguish how children’s experiences in different settings shape specific trajectories of their development (Bornstein et al., 2012). It will also allow us to identify the best ways of integrating interventions into existing health platforms, while helping to achieve the desired outcomes related to targets set for child survival and well-being (United Nations, 2013). The result would leverage better informed national and global policies for early child development.

In 2001 Tomlinson and Swartz wrote to the editors of the 12 journals included in their review to assess whether there was an acceptance bias for articles from HIC. Five journals did not reply, and six journals stated that they did not have adequate information on submission rates from developing countries. Only one journal could comment on these submission rates, stating that they had not received any from an LMIC or with data gathered in an LMIC (Tomlinson & Swartz, 2003). Due to the previous inability to comment on the acceptance bias, the same effort was not made for this updated review. Although an active bias against submissions dealing with developed countries seems unlikely, it remains to be explored whether there is any implicit bias in the acceptance rates of articles from different parts of the world.

Our method allowed us to survey only certain specific journals, and some contributions relevant to the field of infant mental health could not be accessed in our searches. These would include for example, journals dealing with mental health issues more generally (e.g., British Journal of Psychiatry) and with broader health issues (e.g., The Lancet). As with results from Tomlinson and Swartz (2003), the discrepancies observed are still indicative of progress needed to bridge the 10/90 gap.

Footnotes

Denotes articles until the end of December 2012

References

- Arnett JJ. The neglected 95%: why American psychology needs to become less American. Am Psychol. 2008;63(7):602–614. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.63.7.602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Shlomo Y, Kuh D. A life course approach to chronic disease epidemiology: conceptual models, empirical challenges and interdisciplinary perspectives. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31(2):285–293. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH. Human infancy…and the rest of the lifespan. Annu Rev Psychol. 2014;65:121–158. doi: 10.1146/annurev-psych-120710-100359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bornstein MH, Britto PR, Nonoyama-Tarumi Y, Ota Y, Petrovic O, Putnick DL. Child development in developing countries: introduction and methods. Child Dev. 2012;83(1):16–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2011.01671.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins PY, Insel TR, Chockalingam A, Daar A, Maddox YT. Grand challenges in global mental health: integration in research, policy, and practice. PLoS Med. 2013;10(4):e1001434. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper PJ, Landman M, Tomlinson M, Molteno C, Swartz L, Murray L. Impact of a mother-infant intervention in an indigent peri-urban South African context: pilot study. Br J Psychiatry. 2002;180:76–81. doi: 10.1192/bjp.180.1.76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamel RE. The dominance of English in the international scientific periodical literature and the future of language use in science. AILA Review. 2007;20(1):53–71. [Google Scholar]

- Henrich J, Heine SJ, Norenzayan A. The weirdest people in the world? Behav Brain Sci. 2010;33(2–3):61–83. doi: 10.1017/S0140525X0999152X. discussion 83-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieling C, Baker-Henningham H, Belfer M, Conti G, Ertem I, Omigbodun O, Rahman A. Child and adolescent mental health worldwide: evidence for action. Lancet. 2011;378(9801):1515–1525. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60827-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kieling C, Rohde LA. Child and adolescent mental health research across the globe. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(9):945–947. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klasen H, Crombag A-C. What works where? A systematic review of child and adolescent mental health interventions for low and middle income countries. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2013;48:595–611. doi: 10.1007/s00127-012-0566-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein PS, Rye H. Interaction-oriented early intervention in Ethiopia: the MISC approach. Infants and Young Children. 2004;17:340–354. [Google Scholar]

- Lund C, Tomlinson M, De Silva M, Fekadu A, Shidhaye R, Jordans M, Patel V. PRIME: a programme to reduce the treatment gap for mental disorders in five low- and middle-income countries. PLoS Med. 2012;9(12):e1001359. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1001359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mari JJ, Patel V, Kieling C, Razzouk D, Tyrer P, Herrman H. The 5/95 gap in the indexation of psychiatric journals of low- and middle-income countries. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2010;121(2):152–156. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2009.01476.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Population Reference Bureau. 2013 World Population Data Sheet: Population Reference Bureau. 2013a. [Google Scholar]

- Population Reference Bureau. World Population Data Sheet. 2013. Washington: Population Reference Bureau; 2013b. [Google Scholar]

- Saxena S, Paraje G, Sharan P, Karam G, Sadana R. The 10/90 divide in mental health research: trends over a 10-year period. Br J Psychiatry. 2006;188:81–82. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.105.011221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson M, Doherty T, Jackson D, Lawn JE, Ijumba P, Colvin M, Chopra M. An effectiveness study of an integrated, community-based package for maternal, newborn, child and HIV care in South Africa: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials. 2011;12:236. doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-12-236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson M, Swartz L. Imbalances in the knowledge about infancy: The divide between rich and poor countries. Infant Mental Health Journal. 2003;24(6):547–556. doi: 10.1002/imhj.21462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. The Millennium Development Goals Report, 2013. New York: United Nations; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Walker SP, Chang SM, Powell CA, Simonoff E, Grantham-McGregor SM. Effects of psychosocial stimulation and dietary supplementation in early childhood on psychosocial functioning in late adolescence: Follow-up of randomised controlled trial. British Medical Journal. 2006;333:472. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38897.555208.2F. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker SP, Wachs TD, Gardner JM, Lozoff B, Wasserman GA, Pollitt E, Carter JA. Child development: risk factors for adverse outcomes in developing countries. Lancet. 2007;369(9556):145–157. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60076-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]