Abstract

In preparation for designing and undertaking trials of strategies that can modulate “innate inflammation” to improve outcomes of ischemic injury, consideration of approaches that have managed cellular inflammation in ischemic stroke are instructive. Robust experimental work has demonstrated the efficacy (and apparent safety) of targeting PMN leukocyte–endothelial cell interactions in the early moments following focal ischemia onset in model systems. Four clinical trial programs were undertaken to assess the safety and efficacy of inhibitors to PMN leukocyte interactions with the endothelial cell during ischemic stroke. Experiences in those clinical trial programs indicate specific limitations that halted progress in this line of investigation before an adequate hypothesis test could be achieved. Although innate inflammation is a central part of injury evolution following focal ischemia, great care in the translation from experimental studies to Phase I/II clinical safety assessments and to the design and conduct of Phase III trials is needed.

Keywords: PMN leukocytes, ischemic stroke, inflammation, clinical studies, treatment

Introduction

One component of “innate inflammation” is the contribution that cellular inflammation from systemic leukocyte subpopulations makes to the development of cerebral injury following focal ischemia. Based broadly on strong experimental work, Phase II and III studies to test the impact of activated leukocytes on brain tissue in the setting of ischemic stroke were undertaken.1 The general hypothesis to be tested stated that inhibition of polymorphonuclear (PMN) leukocyte adhesion, activation, or transmigration is likely to significantly reduce the ultimate volume and neurological impact of focal ischemic injury, by inhibiting the development of infarction. Important for the design of clinical trials to determine the benefit-risk relationships of interventions in “innate inflammation” are concerns arising from the clinical studies that have already tested various components of this hypothesis.

The microvessel as interface

The exquisite sensitivity of neurons to ischemic injury is paralleled by events that happen rapidly following the onset of focal ischemia in the microvessels. The endothelial cell layers of cerebral microvessels provide the brain tissue interface for cellular inflammation.2 Responses of cerebral microvessels to ischemia include i) loss of the permeability barrier with the extravasation of plasma constituents, ii) leukocyte adhesion to endothelial cell-leukocyte receptors leading to transmigration of leukocytes, and/or obstruction of the microvasculature (the focal “no-reflow” phenomenon), and iii) processes that lead to degradation of the basal lamina matrix.3–7 These changes in the microvasculature vary with the location of the injury in the arterial territory-at-risk, and in the time from injury onset. Of these responses, the adhesion of leukocytes to the activated endothelial cell surface has provided several targets for intervention.

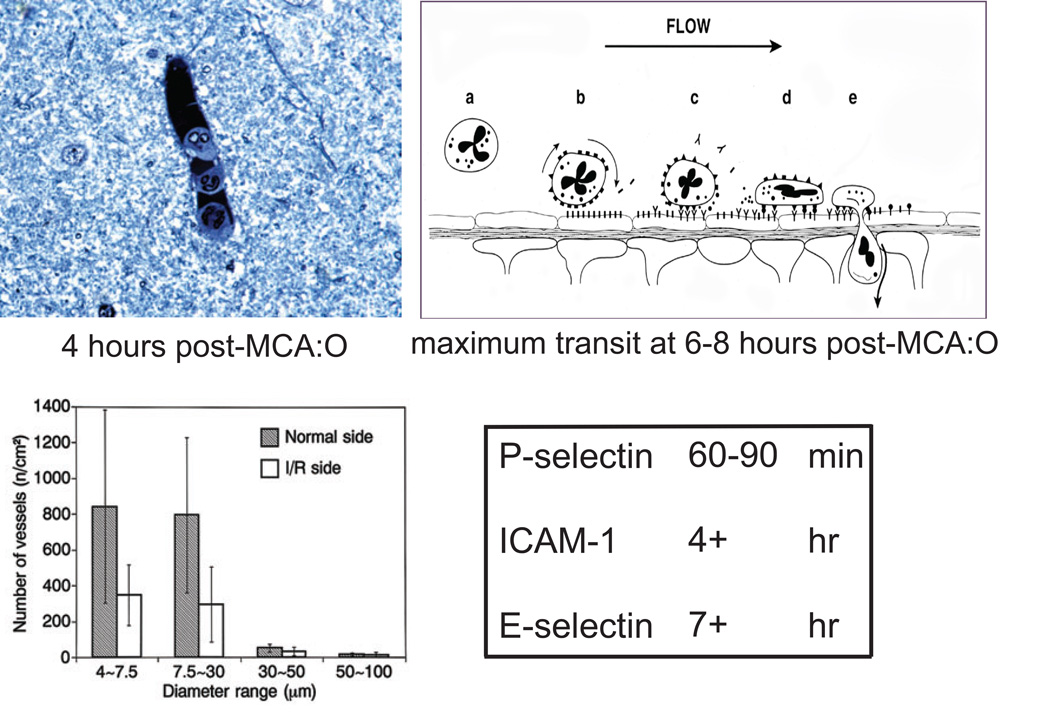

Expression of endothelial cell-leukocyte adhesion receptors on endothelial cells in microvessels activated in the ischemic territory is relatively sequential (Fig. 1). P-selectin appears within 60–90 minutes, ICAM-1 appears within 4 hours, and E-selectin appears 7 hours after the onset of focal ischemia (by middle cerebral artery occlusion, MCA:O).5,6 The maximum transit of human leukocytes is 6–8 hours following MCA:O in the non-human primate. The activation of human leukocytes within the vasculature can, together with activated platelets, cause microvessel obstruction that has been termed focal “no-reflow.” Blockade of the β2-integrin CD18 early during reperfusion of the occluded MCA significantly increases the patency of capillaries and post-capillary venules in the ischemic territory. This implies that disrupting adhesion between PMN leukocytes and the endothelial cell surface early following ischemia onset, during reperfusion, can allow microvascular patency. Endothelial adhesion and PMN leukocyte migration are a complex processes.

Figure 1.

Interaction of PMN leukocytes with activated endothelium within the ischemic territory (clockwise from upper left). Adherence of PMN leukocytes to the endothelial lining of a post-capillary venule 4 hours after MCA:O. Sequence of events involving rolling, firm adhesion, and transmigration of PMN leukocytes through the wall of the post-capillary venule following the onset of focal ischemia. The appearance of endothelial cell-leukocyte adhesion receptors after ischemia onset. Occlusion of cerebral microvasculature (4.0–30.0 µm diameter) observed in the territory undergoing ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) compared with the normoxic territory.3–6

Monocytes follow PMN leukocytes in their incursion into the ischemic territory. Activation of resident microglia and of monocyte-macrophages can contribute to long-term consequences of the inflammatory response.8,9 In the Wistar rat, Garcia et al noted significant invasion of ischemic brain tissue at 24 hours after the onset of focal ischemia.10

Hence, it has been postulated that PMN leukocytes can contribute to cerebral injury following focal ischemia by impairing local blood flow via microvessel obstruction, injuring endothelial cells and extracellular matrix (ECM) by hydrolytic enzymes and free radicals that are generated in the interaction, promoting intravascular thrombus formation together with platelet activation, and expressing cytokines and chemotactic factors that promote expansion of the inflammatory response.

Evidence for the roles of leukocytes in focal cerebral ischemic injury

Early studies in both animal models and patients failed to appreciate the contributions of innate inflammation and cellular inflammation to the evolution of focal ischemic injury and ischemic stroke. Hallenbeck et al first described the potential involvement of leukocyte activation in a limited form of injury to the central nervous system (CNS).11 Subsequently, del Zoppo et al demonstrated the early appearance of PMN leukocytes within hours of the onset the focal ischemia (Fig. 1).3 A number of studies followed, which confirmed the participants in leukocyte-vascular adherence and “no-reflow,” leukocyte transmigration, and activation and receptor exposure on both endothelial cells and PMN leukocytes. Early studies, involving mostly strategies for inhibition of receptor-receptor interactions, and cell reduction techniques, variably confirmed the ability in small animal model systems for inhibition to reduce injury volumes.

Most importantly, knockout preparations with deletions of P-selectin/E-selectin, intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), or NADPH oxidase demonstrated significant decreases in infarction volume in those murine preparations.12–16 Of those, deletion of NADPH oxidase, an enzyme involved in the PMN leukocyte respiratory burst, reduced infarction volume significantly. Studies from several laboratories examined the impact of the blockade of P-selectin/E-selection, ICAM-1, or ICAM-1 in the presence of rt-PA on infarction development. The majority of studies demonstrated significant reduction in injury volume in small animal models. Those observations, and the known role of PMN leukocytes in secondary injury in the myocardium and skeletal muscle, suggested targets for clinical intervention in ischemic stroke.

Clinical strategies

Acute application of anti-inflammatory strategies intended to block cell-mediated inflammation, based on experimental work, have so far addressed three targets in evolving ischemic stroke patients using four strategies (Table 1). These include a humanized monoclonal antibody (MoAb) against ICAM-1 expressed on activated endothelial cells, a humanized MoAb against PMN leukocyte CD18, the recombinant neutrophil inhibitory factor (rNIF) that prevents neutrophil adhesion, and an inhibitor of the action of the interleukin-1β (IL-1β), the interleukin-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1ra). Trials were designed at various stages, either Phase II or Phase III. So far, no Phase III acute interventional trial has been successfully completed that demonstrated improvement with the intervention.

TABLE 1.

Strategies to inhibit impact of cellular inflammation acutely in ischemic stroke.

| agent | design | phase | status |

|---|---|---|---|

| anti-ICAM-1 MoAb | trial of efficacy and safety of enlimomab (RR 1.1) vs placebo* | III | complete |

| anti-CD 18 MoAb | trial of Hu23F2G anti-adhesion to limit cytotoxic injury un acute ischemic stroke (HALT stroke)* | pilot III | complete aborted |

| rNIF | trial of recombinant neutrophil inhibitory factor in acute stroke* | II | complete |

| IL-1ra | trials of IL-1β inhibition in acute ischemic stroke | II | complete |

multi-centre

Trials

Enlimomab study

This study tested the hypothesis that PMN leukocyte adherence to endothelium and transmigration could be successfully blocked with the endothelial cell adhesion receptor ICAM-1 inhibitor RR 1.1 within 6 hours of stroke symptom onset.17 Improvement in 3-month disability outcome and in mortality at one year were the intended efficacy outcome events. Stable RR1.1 plasma concentrations were obtained throughout the infusion period. However, the enlimomab preparation had a significantly negative effect on survival in treated patients, compared with placebo. Indeed, a significant worsening of outcome at 3 months by the modified Rankin Score (mRS) was observed (2p = 0.004).18 An excess of fevers and mortality were seen in the enlimomab group, which were related to the RR1.1 preparation. However, the cause of deterioration of these patients was not the fever per se. Hence, those who received enlimomab displayed reduced functional recovery by mRS, Barthel index and NIHSS at day 90, increased mortality at day 90, increased incidence of serious adverse events, and more frequent infections.

Contributors to CNS injury that might explain these observations included the development of human anti-mouse antibodies, the activation of intracellular signaling of the endothelium through ICAM-1, complement activation by the enlimomab preparation, and activation of non-vascular cells in the brain. A subsequent study, “bedside-to-bench-to-bedside,” demonstrated that sequential infusion of heterologous antibodies in a rodent focal ischemia model could significantly increase cerebral injury volume.19 This suggested that augmentation of in situ cerebral inflammatory processes was probably at play.

The HALT stroke study

The hypothesis of this study was that inhibition of PMN leukocyte adherence and transmigration by blocking the adhesive function of PMN leukocyte β2 integrin CD18 with the humanized MoAb Hu23F2G, within 12 hours of stroke symptom onset, could improve 3-month disability and outcome at one year. A dose-escalation study against placebo was performed in Phase II format to determine the safety of this approach and potential dose efficacy. A concentration of 1.5 mg/kg Hu23F2G in single dose was found to be safe, with a modicum of increased fever. However, a twice-daily infusion of Hu23F2G at this dose appeared to produce an improvement in mRS score. Based on this Phase II data, a Phase III study was performed. However, the sponsor terminated the study at first-interim analysis, when a “futility analysis” suggested that no benefit of the treatment would occur if the study was completed. No public information regarding the database, outcomes, safety issues, or relative number of SAEs has appeared.20

rNIF stroke study (ASTIN)

The hypothesis tested in this study was that inhibition of PMN leukocyte adherence and transmigration by blocking PMN leukocyte β2 integrin CD18 with recombinant NIF within 6 hours of stroke symptom onset could improve 3-month disability outcome, measured by mRS. rNIF is a 41 kDA CD18 antagonist from hookworm species that interacts with domain I of CD11b/CD18.21 A Phase II study was performed to examine the effects of rNIF in patients, based upon a limited experimental data set in rodent MCA:O models.22,23 The Phase II clinical trial design was based on a Bayesian approach, wherein patients were placed in open dose-rate cohorts, depending upon previous dosing experience in the series.24,25 In the trial, 966 patients were enrolled in 16 dose tiers, but no dose-rate effect was observed compared to placebo. This result differed from a theoretical model upon which the study design was based. However, the results at week 10 did not differ from the results at the end of the study (week 66). The project did not continue after completion of this trial.

IL-1ra stroke study

Here, the hypothesis stated that inhibition of IL-1β, generated in the setting of ischemic stroke from CNS sources, would be safe and reduce cerebral injury assayed by clinical outcomes. Significant experimental background suggested that in rodents, the receptor antagonist IL-1ra, already available for clinical use in arthritis, would be safe and beneficial.26,27 The agent was applied within 12 hours of stroke symptom onset and was intended to improve disability outcome at 3 months. In a small pilot study, 34 patients were randomized to 2 mg/kg/hr over 72 hours or matched placebo.28 No adverse events were attributed to the IL-1ra treatment among 34 patients randomized, and SAEs constituted 5 patients in each group. There was a non-significant increase in patients with mRS 0–1. A second dose-ranging study was recently reported.29 To date, no Phase III study has been completed.

Limitations in the anti-inflammatory approaches to stroke

Based upon a strong experimental background for the early clinical work, the hypothesis that inhibition of PMN leukocyte adhesion, activation, and/or transmigration could be beneficial in the development of focal ischemia in patients has received a very limited test. Failing a remarkable improvement in outcome, these studies together have been taken to suggest that the hypothesis has failed. In actuality, the theoretical hypothesis based upon pre-clinical data has not been fully tested in the clinical setting.

A number of limitations have been exposed variously by this prospective clinical experience that owe to the application of pre-clinical data to the clinical setting, design issues, suitability of the agent for testing, and outcome interpretation. Among these (Table 2), failure to translate observations from animal models into the clinic and from Phase II studies into Phase III studies stand out. Perhaps more central to the problem of translation has been the failure to understand how cellular inflammation causes injury in the CNS, and the probability that endogenous mechanisms of inflammation (“innate inflammation”) are set into motion, which can contribute to the injury evolution beginning with the initial ischemic event.

TABLE 2.

Limitations of clinical trials undertaken to block cellular inflammation acutely in ischemic stroke.

| intervention exacerbated evolving CNS injury |

| failure to apply basic principles of immunology |

| inadequate understanding of brain injury mechanisms |

| exacerbation of systemic effects |

| exacerbation of pre-existing infection or inflammation |

| failure to require an adequate pre-clinical dataset to translate experiment to clinical trial design |

| failure to translate observations from phase II studies to phase III |

| use of “novel” trial design elements not previously or adequately tested |

| failure to adequately validate outcome measures to be used |

| failure to appreciate alternative hypotheses |

| conflict of interest |

| failure of the fundamental hypothesis |

Those studies exposed a number of weaknesses that must be addressed in future trials of interventions to modulate “innate inflammation.” These include the appropriate application of basic principles of immunology, a more thorough understanding of brain injury mechanisms, the need for an adequate pre-clinical data set to translate experiments to clinical trial design, the translation of observations from Phase II studies into Phase III studies, avoidance of “novel” trial design elements not previously or adequately tested, the need to properly validate the outcome measures used, elimination of conflict of interest, and full consideration of alternative hypotheses.

Beyond cellular inflammation

Nearly ten years on from the initial experience with cellular inflammation, new insights into the nature of cell-cell interactions and receptor mediated processes have led to further understanding of PMN leukocyte activation and transmigration. The vascular cell responses to ischemia include not only the endothelium, but also the contributions of astrocytes, pericytes, and microglial cells, which themselves each have a specific response to ischemia that involve elements of cellular inflammation. Furthermore, each of the cells within the “neurovascular unit” have a response to ischemia that involves inflammation.2 An appreciation of these elements and their role in innate inflammation will be necessary for future success in clinical trials.

These considerations indicate that the fundamental hypothesis that reducing or ablating the impact of leukocyte-mediated injury on the evolution of the infarction following the onset of focal CNS ischemia has not been fully or adequately tested, and therefore remains open. Appreciation for the way in which the components of the “neurovascular unit” can interact with each other may be very important in understanding both the endogenous inflammatory responses to ischemia and how events within the cerebral microvasculature can affect processes within the neuropil.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants NS 026945, NS 053716, and NS 038710 from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.del Zoppo GJ. Lessons from stroke trials using anti-inflammatory approaches that have failed. In: Dirnagl U, Elger B, editors. Ernst Schering Stifung Workshop 47: Neuroinflammation in Stroke. Berlin: Springer Verlag; 2004. pp. 155–184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.del Zoppo GJ. Inflammation and the neurovascular unit in the setting of focal cerebral ischemia. Neuroscience. 2009;158:972–982. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.del Zoppo GJ, et al. Polymorphonuclear leukocytes occlude capillaries following middle cerebral artery occlusion and reperfusion in baboons. Stroke. 1991;22:1276–1284. doi: 10.1161/01.str.22.10.1276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mori E, et al. Inhibition of polymorphonuclear leukocyte adherence suppresses no-reflow after focal cerebral ischemia in baboons. Stroke. 1992;23:712–718. doi: 10.1161/01.str.23.5.712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Okada Y, et al. P-selectin and intercellular adhesion molecule-1 expression after focal brain ischemia and reperfusion. Stroke. 1994;25:202–211. doi: 10.1161/01.str.25.1.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haring H-P, et al. E-selectin appears in non-ischemic tissue during experimental focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 1996;27:1386–1392. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.8.1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.del Zoppo GJ, von Kummer R, Hamann GF. Ischemic damage of brain microvessels: Inherent risks for thrombolytic treatment in stroke. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 1998;65:1–9. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.65.1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mabuchi T, et al. Contribution of microglia/macrophages to expansion of infarction and response of oligodendrocytes after focal cerebral ischemia in rats. Stroke. 2000;31:1735–1743. doi: 10.1161/01.str.31.7.1735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.del Zoppo GJ, et al. Microglial activation and matrix protease generation during focal cerebral ischemia. Stroke. 2007;38:646–651. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000254477.34231.cb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Garcia JH, et al. Influx of leukocytes and platelets in an evolving brain infarct (Wistar rat) Am. J. Pathol. 1994;144:188–199. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dutka AJ, Kochanek PM, Hallenback JM. Influence of granulocytopenia on canine ischemia induced by air embolism. Stroke. 1989;20:390–395. doi: 10.1161/01.str.20.3.390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Connolly ES, Jr, et al. Exacerbation of cerebral injury in mice that express the P-selectin gene: Identification of P-selectin blockade as a new target for the treatment of stroke. Circ. Res. 1997;81:304–310. doi: 10.1161/01.res.81.3.304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Connolly ES, Jr, et al. Cerebral protection in homozygous null ICAM-1 mice after middle cerebral artery occlusion. Role of neutrophil adhesion in the pathogenesis of stroke. J. Clin. Invest. 1996;97:209–216. doi: 10.1172/JCI118392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soriano SG, et al. Intercellular adhesion molecule-1-deficient mice are less susceptible to cerebral ischemia-reperfusion injury. Ann Neurol. 1996;39:618–624. doi: 10.1002/ana.410390511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Soriano SG, et al. Mice deficient in Mac-1 (CD11b/CD18) are less susceptible to cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury. Stroke. 1999;30:134–139. doi: 10.1161/01.str.30.1.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walder CE, et al. Ischemic stroke injury is reduced in mice lacking a functional NADPH oxidate. Stroke. 1997;28:2252–2258. doi: 10.1161/01.str.28.11.2252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schneider D, et al. Safety, pharmocokinetics and biological activity of enlimomab (anti-ICAM-1 antibody): an open-label, dose escalation study in patients hospitalized for acute stroke. Eur. Neurol. 1998;40(2):78–83. doi: 10.1159/000007962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Enlimomab Acute Stroke Trial Investigators. Use of anti-ICAM-1 therapy in ischemic stroke: results of the Enlimomab Acute Stroke Trial. Neurology. 2003;57:1428–1434. doi: 10.1212/wnl.57.8.1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Furuya K, et al. Examination of several potential mechanisms for the negative outcome in a clinical stroke trial of enlimomab, a murine anti-human intercellular adhesion molecule-1 antibody: a bedside-to-bench study. Stroke. 2001;32:2665–2674. doi: 10.1161/hs3211.098535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.ICOS STROKE TRIAL. [Accessed 20 April, 2000];ICOS Halts Trial of Stroke Drug, Reports Q1 Net Loss. 2000 http://bizyahoocom/rf/000420/mfhtml. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Muchowski P, et al. Functional interaction between the integrin antagonist neutrophil inhibitory factor and the I domain of CD11b/CD18. J Biological Chem. 1994;269:26419–26423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jiang N, et al. Neutrophil inhibitory factor is neuroprotective after focal ischemia in rats. Ann Neurol. 1995;38:935–942. doi: 10.1002/ana.410380615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jiang N, Chopp M, Chahwala S. Neutrophil inhibitory factor treatment of focal cerebral ischemia in the rat. Brain Res. 1998;788:25–34. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(97)01503-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Krams M, et al. Acute Stroke Therapy by Inhibition of Neutrophils (ASTIN): an adaptive dose-response study of UK-279,276 in acute ischemic stroke. Stroke. 2003;34:2543–2548. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000092527.33910.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grieve AP, Krams M. ASTIN: a Bayesian adaptive dose-response trial in acute stroke. Clin. Trials. 2005;2:340–351. doi: 10.1191/1740774505cn094oa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Loddick SA, Rothwell NJ. Neuroprotective effects of human recombinant interleukin-1 receptor antagonist in focal cerebral ischaemia in the rat. J. Cereb. Blood Flow Metab. 1996;16:932–940. doi: 10.1097/00004647-199609000-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rothwell NJ, Allan S, Toulmond S. The role of interleukin-1 in acute neurodegeneration and stroke:pathophysiological and therapeutic implications. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;100:2648–2652. doi: 10.1172/JCI119808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Emsley HC, et al. A randomised phase II study of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist in acute stroke patients. J Neurol Neurosurg. Psychiatry. 2005;76:1366–1372. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.2004.054882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Galea J, et al. Intravenous anakinra can achieve experimentally effective concentrations in the central nervous system within a therapeutic time window: results of a dose-ranging study. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2010 doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2010.103. Epub 2010 July 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]