Abstract

Because of its ability to create structures of nanoscale dimension with large aggregate particle surface area-to-volume ratios, nanotechnology offers new opportunities to treat drug poisonings. Emulsion-based nanoparticles (diameter: 118.4 nm) extracted bupivacaine from the aqueous phase in a physiological salt solution and attenuated the drug’s cardiotoxicity in guinea pig heart to a greater extent than did a macroemulsion (432.0 nm). Additionally, nanoparticles sequestered bupivacaine from the aqueous phase of human blood and merit further investigation in animal models of intoxication.

Nanotechnology has been heralded as a means to improve health care by providing revolutionary advances in medical diagnostics and therapeutics.1–5 One medical application of nanotechnology revolves around the potential ability of nanoparticles to mitigate the effects of toxic concentrations of pharmaceuticals. The promise of using particle technology to treat drug overdose emerged when Weinberg and colleagues demonstrated that treatment of rats with submicron lipid particles markedly increased the dose of bupivacaine, a potent local anesthetic, necessary to cause in vivo hearts to cease beating (i.e., cardiac asystole) in rats.6 The reduction in free bupivacaine concentration was attributed to partitioning of the anesthetic from the aqueous phase in plasma into the oil core of the macroemulsion where the drug could not exert a pharmacological effect. We hypothesize that smaller emulsion particles (i.e., nanoemulsions) will even more effectively partition local anesthetics from an aqueous environment into the lipid core or onto the surface interface. For constant oil content, the smaller radii of nanoemulsion particles create a much greater aggregate interfacial area between the particles and their environment than is present for macroemulsions. Greater interfacial area should lead to more rapid and effective portioning of lipophilic drugs onto the oil/water interface and ultimately into the oil core. While sequestered on the surface or core of nanoparticles, a drug will be inactive and unable to cause cardiac toxicity (e.g., inhibition of sodium ion channels in the heart).

Nanoemulsion Synthesis and Characterization

A soybean phosphatidylcholine nanoemulsion was synthesized as previously described because infusions (0.5 mL/kg) in rodents did not cause any adverse physiological effects.7 Intralipid, a commercially available macroemulsion, was obtained from Baxter Healthcare Corporation (Deerfield, IL). The effective particle size and polydispersity of the nanoemulsion and Intralipid solutions were measured by the dynamic light scattering method using a submicron particle size analyzer (90Plus, Brookhaven Instruments Corporation, Holtsville, NY). Particle population diameter densities were fitted to a three-parameter Gaussian distribution equation (GraphPad Prism 2.01, GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA):

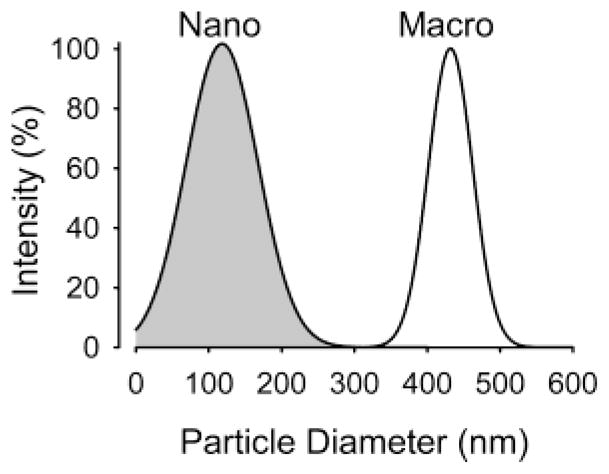

where y is the absorbance of a population of particles with diameter x, area is the area under the intensity curve, σ is the standard deviation of the population, and μ is the mean diameter of the particles. The macroemulsion (432.0±30.2 nm) and nanoemulsion (118.4±49.5 nm) particle size distributions (mean±S. D.) were normally distributed and significantly different (Figure 1). Based on the graphical and numerical data, minimal-to-no overlap of particle size occurred as the midpoint dimension (i.e., 275 nm) between the mean particle diameters was >3 and >5 standard deviations for nanoemulsion and macroemulsion particles, respectively.

Figure 1.

Size dispersion of nanoemulsion and macroemulsion particles. Shown is the intensity normalized to maximal intensity plotted against the particle diameter. The nanoemulsion and macroemulsion particle populations are noted in gray and white colors, respectively.

Extraction of Bupivacaine in Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS)

Samples were prepared by spiking blank PBS (g/L: NaCl 8.0, KCl 0.2, Na2HPO4 1.44, and KH2PO4 0.24 with pH adjusted to 7.40 using NaOH or HCl) with a stock bupivacaine solution (2 mg/mL) to yield three bupivacaine concentrations (1, 25, 200 μM). Following equilibration (37 °C, 1 h) ultrafiltration was performed to remove nanoemulsion or macroemulsion particles using micropartition centrifugation tubes (Amicon Centrifree, Millipore, Inc., Bedford, MA; 30 kDa cut off) spun at 1800× g for 1 h. Chromatographic analysis was performed in quadruplicate for bupivacaine in the ultrafiltrates using a HPLC (Alliance, Waters Inc., Milford, MA) with a 2695 separation module with online degassing and an automated injection and sampling system, coupled to a photodiode array detector (Waters 996). Samples were run on a C18 column (4.6 × 250 mm i.d., Waters, Inc). A 10-min, isocratic elution with a mobile phase consisting of acetonitrile (HPLC Grade, Sigma Chemical Corp.)/phosphate buffer (pH =3.5, 50 mM) in a ratio of 30:70 v/v was employed. The flow rate was 1.5 mL/min with UV detection at 210 nm. At constant concentration of oil for the nanoemulsion or Intralipid, the nanoemulsion removed a significantly greater fraction of bupivacaine than did Intralipid (P < 0.001) for all concentrations of bupivacaine studied. At 1, 25, and 200 μM bupivacaine, the nanoemulsion sequestered 62.2±8.0, 73.8±4.2, and 75.4±0.02% of the anesthetic, whereas Intralipid extracted 52.8±7.1, 56.6±0.6, and 55.4±0.1% from free, aqueous form. Based on these measurements, several binding parameters of nanoemulsion or macroemulsion for bupivacaine were calculated (Table 1).

Table 1.

Binding Parameters of Nanoemulsion-Based Nanoparticles or Macroemulsion (Intralipid) for Bupivacaine in Phosphate Buffered Salinea

| bupivacaine (μM) | Pc | total bupivacaine molecules bound in incubation media (1 mL) | bupivacaine molecules bound per particle | particle interfacial area (nm2) occupied per bupivacaine molecule |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| nanoemulsion | ||||

| 1 | 165 | 3.746 × 1014 | 33 | 1,359 |

| 25 | 281 | 1.111 × 1016 | 961 | 45.8 |

| 200 | 307 | 9.089 × 1016 | 7,863 | 5.60 |

| macroemulsion | ||||

| 1 | 113 | 3.192 × 1014 | 1,342 | 437 |

| 25 | 131 | 8.529 × 1015 | 35,540 | 16.4 |

| 200 | 81 | 5.373 × 1016 | 225,800 | 2.60 |

Note: See Supporting Information for mathematical derivations.

Extraction of Bupivacaine from Human Blood

Human blood (n = 6) was aspirated by phlebotomy into heparinized syringes and divided into 1 mL samples. Bupivacaine (1000 μM) was spiked into blood in a manner similar to that described previously for PBS media. Samples were placed in a temperature-controlled (37 °C) gyrotory water bath shaker (model G 76, New Brunswick Scientific, Edison, NJ) and mixed for 10 min at 3 Hz. The tubes were then removed from the bath and spun at 2500 rev/min for 15 min in a fixed-angle centrifuge (Marathon 8K, Fisher Scientific) to separate the tissue into cellular and plasma phases. The plasma supernatant was aspirated and centrifuged in micropartition tubes in order to obtain ultrafiltrate free from plasma protein or particles. The nanoemulsion extracted a significant fraction of bupivacaine in a concentration-dependent manner with greater fractions of bupivacaine (10.4±0.2, 25.8±0.1, 29.2±0.2, 35.2±0.4%) being extracted with an increasing concentrations (1.0, 1.5, 2.0, and 2.5%, respectively) of nanoemulsion. In this data, the nanoemulsion concentration was calculated based on the fraction of the system composed of oil (weight in weight).

Attenuation of Cardiotoxicity in Guinea Pig Heart

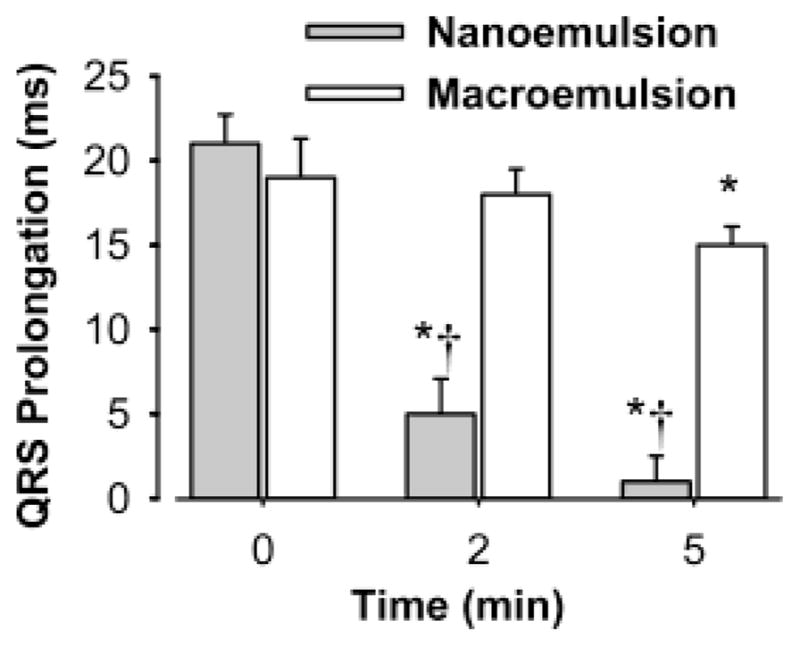

Rodent hearts were extracted and instrumented similar to previous reports from this laboratory.8 In this model, we used electronic cursors to measure the QRS interval of the electrogram that represents the summation of all sodium ionic currents in the ventricles. The QRS interval served as a “biosensor” of free bupivacaine concentrations because it depends on Na+ channel conductance that is blocked by bupivacaine in a concentration-dependent manner. The baseline QRS intervals were 26.0±1.7 and 25.8±1.5 ms for the nanoemulsion (n = 5) and macroemulsion (n = 5) groups, respectively (P = 0.85). Administration of bupivacaine (5 μM) significantly increased the QRS interval for both groups of hearts to a similar extent (Figure 2). Treatment of the bupivacaine-intoxicated hearts with either a nanoemulsion or macroemulsion significantly reduced the QRS interval. However, the effect of the nanoemulsion was significantly greater and more rapid than that of the macroemulsion. At time 5 min, the QRS interval for hearts treated with the nanoemulsion did not significantly vary from the value measured during control conditions (P = 0.92).

Figure 2.

Time-dependent attenuation of bupivacaine (5 μM)-induced QRS prolongation in guinea pig isolated heart by either a macroemulsion (n = 5, 1% w/w oil content) or a nanoemulsion (n = 5, 1% w/w oil content). Data shown is the mean±standard deviation. P < 0.05: *, compared to 0 min; †, compared to macroemulsion. Repeated-measures analysis of variance followed by Student–Newman–Keuls testing was used to analyze multiple comparisons for QRS prolongation. Hearts were paced at 200 beats/min.

The marked differences in the attenuation of QRS interval prolongation between nanoemulsion and macroemulsion observed in isolated heart are greater than might be expected from the extraction experiments in PBS detailed previously. Based on findings from the PBS experiments, one would expect that the nanoemulsion and macroemulsion particles would extract 62–74% and 53–57% of 5 μM bupivacaine, respectively, from the buffered Krebs–Henseleit solution used to perfuse the isolated hearts. Since QRS interval prolongation reflects the free bupivacaine concentration, the relative changes in the QRS interval would be expected to be similar to proportional decrements in the free bupivacaine due to extraction by particles. Probably, this difference between PBS and isolated heart experiments is primarily due to the shape of the concentration–response curve for bupivacaine to prolong the QRS interval and to the exact concentration of bupivacaine selected for this investigation. At 5 μM bupivacaine, small changes in the free concentration of bupivacaine lead to relatively large changes in the QRS interval (i.e., steep section of the concentration–response curve) compared to bupivacaine concentrations <1 μM (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Concentration-response relationship for bupivacaine to prolong the QRS interval in guinea pig isolated heart perfused with Krebs–Henseleit solution. Data shown is the mean±standard deviation for four hearts. P < 0.05: *, compared to 0 μM bupivacaine; †, compared to the immediate lesser concentration of bupivacaine (e.g., 3 μM compared to 1 μM). Repeated-measures analysis of variance followed by Student–Newman–Keuls testing was used to analyze multiple comparisons for QRS interval. Hearts were paced at 200 beats/min.

In this letter, we demonstrated that modulating the size and therefore interfacial area of particles for a fixed oil volume markedly alters the kinetics and magnitude of bupivacaine partitioning into an engineered system of nanoparticles. This change attributed in part to particle size not only significantly reduced the concentration of free bupivacaine in PBS and human whole blood but also reversed QRS prolongation in perfused rodent heart. Furthermore, the reductions in bupivacaine concentrations and cardiotoxicity were superior to Intralipid, a submicron emulsion heralded as a possible antidote to clinical bupivacaine intoxication.6,9 Although these experiments were limited to a single local anesthetic, an understanding of how nanoparticles interact with molecules targeted for scavenging and with biological systems may offer a theoretical framework to guide the development of solutions to rapidly detoxify other anesthetics and drugs from different classes (e.g., tricyclic antidepressants). Such an understanding may enable progression of novel nanotechnological-based therapeutic approaches to treat local anesthetic toxicity that may compliment or supplant traditional therapy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Financial support was provided by the Engineering Research Center for Particle Science & Technology at the University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA via National Science Foundation grant EEC-94-02989 and by the National Institute of General Medical Sciences via RO1 GM63679-01A1. The authors acknowledge Brij Moudgil, Ph.D. for his thoughtful comments and Kendra L. Kuck for her graphical assistance.

Footnotes

Supporting Information Available: Mathematical derivations were used to calculate the partition coefficient, total bupivacaine molecules bound, and bupivacaine molecules bound per particle, and particle interfacial area occupied (%) as presented in Table 1. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Wickline SA, Lanza GM. J Cell Biochem Suppl. 2002;39:90. doi: 10.1002/jcb.10422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taton TA. Trends Biotechnol. 2002;20:277. doi: 10.1016/s0167-7799(02)01973-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guetens G, Van Cauwenberghe K, De Boeck G, Maes R, Tjaden UR, van der GJ, Highley M, van Oosterom AT, de Bruijn EA. J Chromatogr B Biomed Sci Appl. 2000;739:139. doi: 10.1016/s0378-4347(99)00553-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dalsin JL, Hu BH, Lee BP, Messersmith PB. J Am Chem Soc. 2003;125:4253. doi: 10.1021/ja0284963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Couvreur P, Barratt G, Fattal E, Legrand P, Vauthier C. Crit Rev Ther Drug Carrier Syst. 2002;19:99. doi: 10.1615/critrevtherdrugcarriersyst.v19.i2.10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weinberg GL, VadeBoncouer T, Ramaraju GA, Garcia-Amaro MF, Cwik MJ. Anesthesiology. 1998;88:1071. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199804000-00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.von Corswant C, Thoren P, Engstrom S. J Pharm Sci. 1998;87:200. doi: 10.1021/js970258w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Morey TE, Martynyuk AE, Napolitano CA, Raatikainen MJ, Guyton TS, Dennis DM. Anesthesiology. 1997;87:1172. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199711000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weinberg G, Ripper R, Feinstein DL, Hoffman W. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2003;28:198. doi: 10.1053/rapm.2003.50041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.