Abstract

Objective

To evaluate the feasibility of a telehealth psychoeducation intervention for persons with schizophrenia and their family members.

Study Design

Randomized controlled trial.

Participants

30 persons with schizophrenia and 21 family members or other informal support persons.

Interventions

Web-based psychoeducation program that provided online group therapy and education.

Main Outcome Measures

Measures for persons with schizophrenia included perceived stress and perceived social support; for family members, they included disease-related distress and perceived social support.

Results

At 3 months, participants with schizophrenia in the intervention group reported lower perceived stress (p = .04) and showed a trend for a higher perceived level of social support (p = .06).

Conclusions

The findings demonstrate the feasibility and impact of providing telehealth-based psychosocial treatments, including online therapy groups, to persons with schizophrenia and their families.

Keywords: psychoeducation, telehealth, schizophrenia, group therapy, online treatment

It has been estimated that about 1% of the population has schizophrenia (National Institute of Mental Health, 1999). In the United States, more than two million adults are affected by schizophrenia in any given year, and up to 100,000 are in public mental health hospitals on any given day (Lehman & Steinwachs, 1998a; National Institute of Mental Health, 1999). Those with schizophrenia usually require medication for recovery from acute episodes as well as for longer term clinical stabilization, and though necessary for good clinical care, medication is only one component of optimal treatment (Hyman, 1998; Lehman & Steinwachs, 1998a; Lehman & Steinwachs, 1998b). The Patient Outcomes Research Team study of schizophrenia concluded that medical treatment needs to be embedded in a comprehensive psychosocial, rehabilitative, and family treatment program (Lehman & Steinwachs, 1998a).

The development of the diathesis–stress model of schizophrenia (Zubin & Spring, 1977) has had important implications for research on the etiology and course of the illness. The model incorporates an interaction between an inherent vulnerability and stressful environmental stimuli, including social stress, which can trigger onset of illness. Contemporary models of clinical intervention build on the assumption that stress plays not only a role in the etiology and onset of the illness but also an important mediating role influencing the risk for subsequent episodes and longer term course of illness. Thus, the more recent vulnerability–stress–coping model includes the concept of coping as a potentially modifiable variable that can be targeted during treatment. Interventions designed to reduce stress by enhancing coping skills and/or reducing environmental stress are now recognized as an important component of community management (Nuechterlein et al., 1992).

Over the long-term course of treatment, the stress–coping model posits that reduction of stressful environmental stimuli (i.e., stimuli empirically shown to contribute to the risk of relapse) can reduce the stress on persons with schizophrenia and improve their outcomes. Supportive and positive family environments have been shown to be protective factors that improve a patient’s ability to function, whereas family environments with high stress (i.e., those that are emotionally charged, critical, or overstimulating) increase the probability of relapse (Barrowclough & Tarrier, 1992; Nuechterlein et al., 1992; Tarrier et al., 1988). This is the theoretical driving force behind the family psychoeducational approach (C. V. Anderson, Reiss, & Hogarty, 1986), which clinical trials have shown can improve outcomes for community-dwelling persons with schizophrenia (Goldstein, Roderick, Evans, May, & Steinberg, 1978) and the well-being of their families (Hazel et al., 2004; Mari & Streiner, 1994; Szmukler, Herrman, Colusa, Benson, & Bloch, 1996).

Despite their effectiveness, some family psychoeducational programs have found engagement rates as low as 14% (Smith, 1992). Such low participation rates may indicate a need for more convenient ways to hold meetings and a need to address issues of stigma present in face-to-face groups. One comparison of a multifamily face-to-face group intervention versus an individual family intervention offered in each family’s home found low compliance in the multifamily group intervention (Leff et al., 1989). Some of the difference in compliance was due to the difficulties of attending meetings, particularly on a consistent basis, which is a common issue in face-to-face interventions. Other reasons for the low rate of compliance, especially compared with the individual family treatment condition, were believed to be rooted in stigma and the loss of anonymity in the face-to-face group meetings (Leff et al., 1989).

Although family psychoeducational interventions have been shown to be efficacious, several reviewers have lamented their minimal spread beyond research settings (J. Anderson & Adams, 1996; Marshall, 1996). Providers of services face the challenge of devising methods to disseminate the family psychoeducational model that are applicable to routine practice and can retain efficacy (Burns, 1997). The successful transfer of the multifamily psychoeducational model from research and teaching settings to other clinical settings is a significant challenge in an age of scarce resources and increased demand. As service systems strive to conserve resources, innovative research leading to programs that reduce demands on resources will become more important. Strategies such as the Internet-based intervention described here can offer several advantages over more conventional face-to-face interventions. Such programs are accessible worldwide, and although they require the involvement of trained clinicians, they do not require the staff training and investment of resources necessary to set up a new program at each individual clinic or site. Moreover, they offer hope for a wider, more consistent, and more successful transfer and dissemination of treatment models across settings and populations, with the resulting potential for greater public health impact.

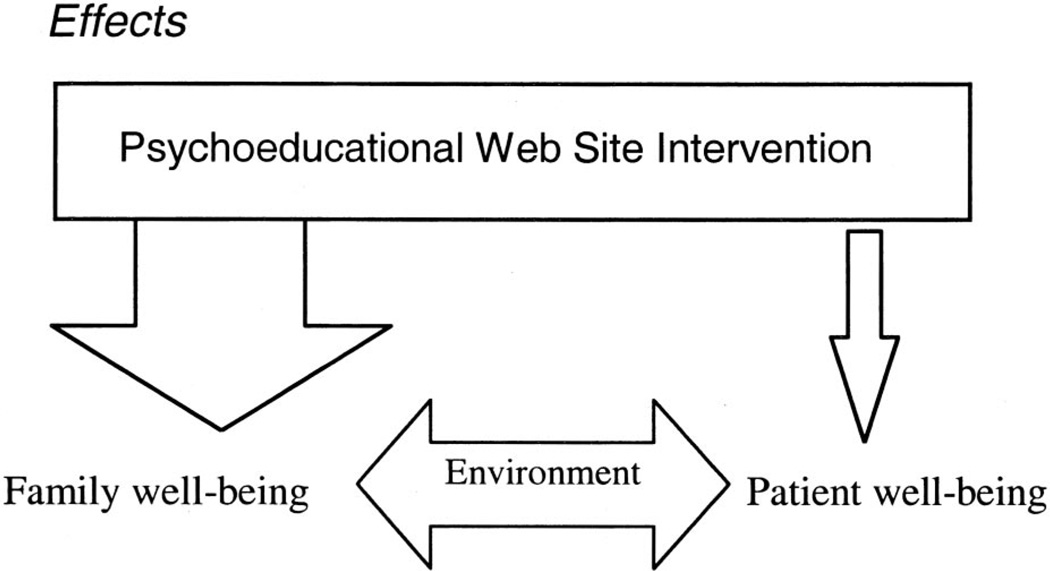

Figure 1 depicts the theoretical framework of the Internet-based intervention presented here (called the Schizophrenia Guide). We hypothesized that the use of the psychoeducational services by persons with schizophrenia would reduce their perceived stress.

Figure 1.

Hypothesized influence of intervention.

We further hypothesized that use of the intervention by families would result in reductions in family stress, improved family support for the persons with schizophrenia, and an improved home environment. These, in turn, would reduce perceived stress for persons with schizophrenia. As depicted in Figure 1, changes in the family environment were hypothesized to have larger effects on reducing the perceived stress of persons with schizophrenia than any direct effects of the intervention itself. This report describes the results of a study designed to assess the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of providing a psychoeducational program to participants’ homes via the Internet.

Method

Participant Recruitment

Staff at in- and outpatient psychiatric care units and psychiatric rehabilitation centers in the Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, area referred to study recruiters individuals with clinical diagnoses of schizophrenia or schizo-affective disorder. Potential participants were asked to identify the person who was their primary informal support person and to ask whether he or she would be interested in learning more about the study. When support persons agreed, the research team provided them with information about participating in the study. All elements of the research protocol were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Pittsburgh.

Enrollment criteria for persons with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder were as follows: age 14 or older; diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder as described in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.; American Psychiatric Association, 1994); one or more psychiatric hospitalizations within the previous 2 years; the ability to speak English and read English, as indicated by the ability to read a paragraph written at a seventh-grade reading level (Graber, Roller, & Kaeble, 1999); and absence of physical limitations that would preclude use of a computer. Enrollment criteria for support persons were as follows: age 18 or older; ability to speak English and read English, as indicated by the ability to read a paragraph written at a seventh-grade reading level (Graber et al., 1999); and absence of physical limitations that would preclude use of a computer. It was anticipated that the intervention would be most effective when both the person with schizophrenia and his or her “closest” family member (the family member who provides him or her with the most support) were enrolled in the study together. However, it was recognized that many persons with schizophrenia have little or no contact with their families or have a reluctance to involve their families in treatment; thus, nonfamily support persons were allowed to enroll. In addition, it was recognized that many persons with schizophrenia are relatively isolated socially and do not have support persons; thus, persons with schizophrenia were allowed to enroll without a support person. Allowing both nonfamily support persons and persons with schizophrenia who did not have a support person to enroll in the study was done in order to test the feasibility of the intervention under the conditions that exist for many persons with schizophrenia and in many community treatment centers.

Participants

Thirty persons with schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder and 21 support persons were randomly assigned (either as individuals with schizophrenia or as dyads, when persons with schizophrenia had a support person) to the telehealth intervention group or the usual care group. The telehealth group had 16 persons with schizophrenia and 11 support persons (i.e., 11 dyads and 5 individuals with schizophrenia without family members or support persons). Seven of the 11 support persons lived with the person with schizophrenia, and 9 of the 11 support persons were family members. The usual care group had 14 persons with schizophrenia and 10 support persons (i.e., 10 dyads and 4 individuals with schizophrenia with- out family members or support persons). Seven of the support persons lived with the person with schizophrenia, and all 11 of the support persons were family members. At baseline, 4 of the dyads in the intervention group who lived together and 3 of the dyads in the usual care group who lived together had computers in their homes. Additional characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Participants

| Persons with schizophrenia/ schizoaffective disorder |

Family/support persons |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | n | % | N | % |

| Diagnosis | ||||

| Schizophrenia | 15 | 50.0 | NA | |

| Schizoaffective | 15 | 50.0 | NA | |

| Gender (female) | 21 | 70.0 | 14 | 66.7 |

| Race | ||||

| Caucasian | 14 | 46.7 | 11 | 52.4 |

| African American | 14 | 46.7 | 8 | 38.1 |

| Other | 2 | 6.7 | 2 | 9.6 |

| Education | ||||

| Some high school | 3 | 10.0 | 3 | 14.3 |

| High school grad | 13 | 43.3 | 6 | 28.6 |

| Some post-high-school education |

14 | 46.7 | 12 | 57.1 |

| Household income | ||||

| < $10,000 | 16 | 53.3 | 10 | 47.6 |

| $10,000-$14,999 | 3 | 10.0 | 3 | 14.3 |

| $15,000-$19,999 | 3 | 10.0 | 2 | 9.5 |

| $20,000-$29,999 | 4 | 13.3 | 3 | 14.3 |

| ≥$30,000 | 4 | 13.3 | 3 | 14.3 |

| Marital status | ||||

| Married | 6 | 20.0 | 10 | 47.6 |

| Widowed | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 4.8 |

| Divorced | 3 | 10.0 | 3 | 14.3 |

| Separated | 1 | 3.3 | 1 | 4.8 |

| Single | 20 | 66.7 | 6 | 28.6 |

Note. For persons with schizophrenia/schizoaffective disorder, mean age = 37.5 years (SD= 10.7); for family/support persons, mean age = 51.52 years (SD= 12.4). NA = not assessed; grad = graduate.

Procedures

Participants assigned to the telehealth intervention condition received computers in their homes as needed. For dyads that lived in separate homes, the computers were installed in the support persons’ homes, unless they had a computer, in which case they were installed in the home of the person with schizophrenia. As a result, two persons with schizophrenia did not have a computer in their homes. Access to the Internet was provided via a dial-up modem and local Internet service provider, paid for by the research project.

Telehealth Intervention: The Schizophrenia Guide Web Site

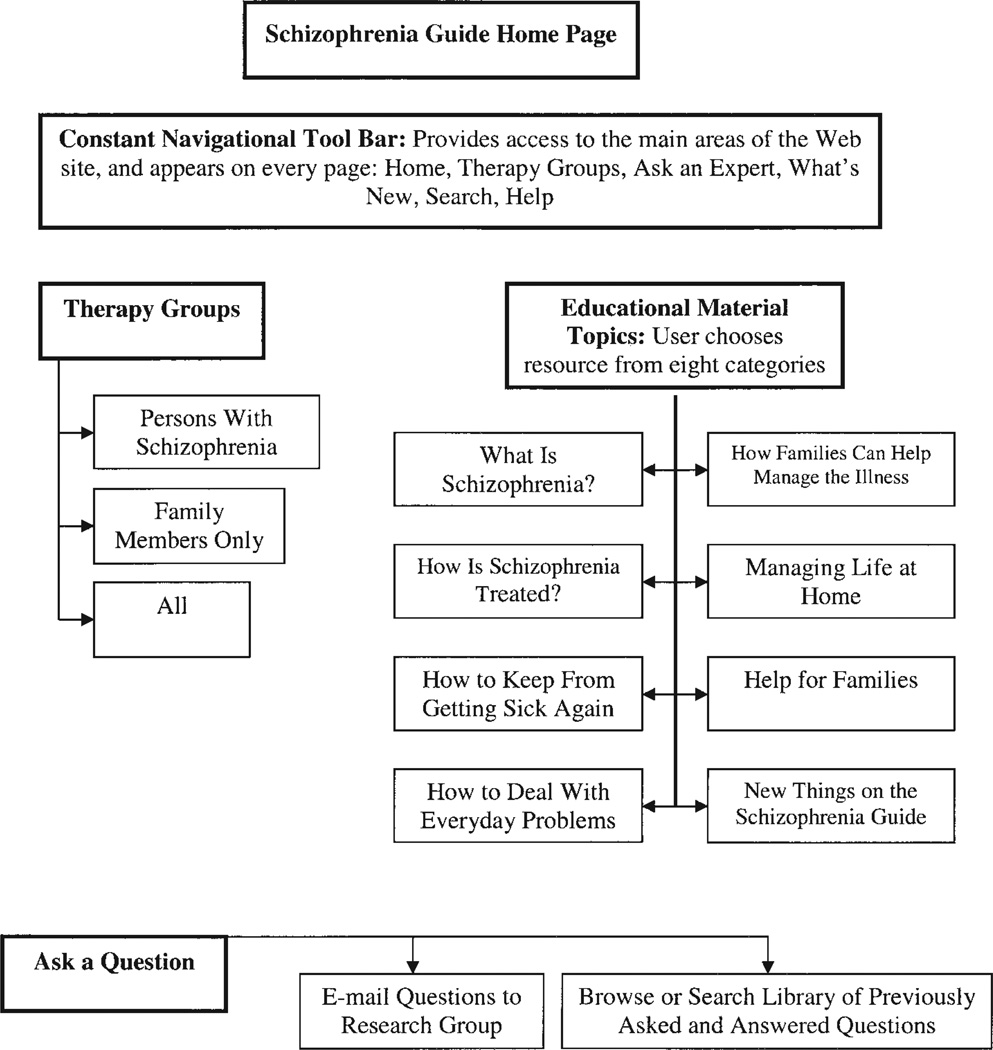

The Schizophrenia Guide software was programmed to collect information on each participant’s usage of the Web site. Each time a page of the site was “visited” by a user (i.e., requested from the server), it was considered a “hit,” and the page, time of day, and user name were stored. Each intervention participant was given a unique login name and password to access the intervention Web site (see Figure 2). To enhance confidentiality, the login name could not be a user’s real name. Communications to and from the site were encrypted with an https connection, which used the Secure Socket Layer capability of the Web server and browsers to provide encryption with the Digital Encryption Standard. The Web site was secured using password protection, and data transferred across the Internet were encrypted.

Figure 2.

Conceptual model of the Schizophrenia Guide home page.

Contents of the Schizophrenia Guide

Selection of the content domains and specific topics for the Schizophrenia Guide was based on information from four sources: (a) interviews with 73 persons with schizophrenia, 31 family members, and 27 professionals who provided services to persons with schizophrenia; (b) previous work with families who had a member with a chronic illness (Rotondi, Sinkule, & Spring, 2005); (c) formal needs assessments of persons with a severe chronic condition and their primary family caregivers (Rotondi, Sinkule, Balzer, & Harris, 2004; Rotondi, Sinkule, Balzer, Harris, & Moldovan, 2002); and (d) guidance from three advisory boards assembled specifically for this project (one composed of family members, one composed of persons with schizophrenia, and one composed of African American mental health professionals who had experience with families in crisis and persons with serious mental illness). Preliminary work involved extensive conceptual modeling and usability testing of the contents, presentation, and design of the Web site, using persons with schizophrenia and, to a lesser extent, family members. Details of the design work and usability testing are described elsewhere (Rotondi, Sinkule, Haas, et al., 2004). A primary challenge in designing the Web site was to make it usable by persons with cognitive deficits, including those who may have had no previous computer experience.

The Schizophrenia Guide provided the following information and services (described in detail below and in Figure 2): (a) three online therapy groups, (b) the ability to ask questions of the experts associated with the project and receive an answer, (c) a library of previously asked and answered questions, (d) activities in the community and news items that focus on mental health issues, and (e) educational reading materials.

Therapy groups

The site provided a Web-based environment for each of three separate and private therapy groups: (a) family members/support persons only (FTG), (b) persons with schizophrenia only (PWSTG), and (c) multifamily therapy group for all intervention participants (MFTG). For each of the groups, bulletin board formats were provided for Internet communication among group members. The groups were facilitated by experienced mental health professionals (master of social work and PhD clinicians) who were trained in the monitoring and management of Web-based interventions. Intervention implementation was guided by a standardized facilitation protocol that included an outline for facilitating the groups and the process for solving problems, based on the manuals of Anderson and McFarlane (C. V. Anderson et al., 1986; McFarlane et al., 1991). The facilitators’ protocol outlined methods to encourage the entire group to be involved in the problem-solving process, thereby promoting the contribution of more ideas, options, and solutions than one family or individual might develop alone.

Ask Our Experts Your Questions

This module allowed users to anonymously ask questions and receive a response. Members of the research team answered these questions or contacted outside experts when additional information was needed.

Questions and Answers Library

The questions and answers from Ask Our Experts Your Questions, with personal information eliminated, were added to the Questions and Answers Library. Initially, the library was seeded with answers to commonly asked questions. The library provided indexed entry to the questions and answers.

Educational and Reading Materials (Articles)

The Web site contained educational materials, including articles on typical family responses to schizophrenia, emotional problems experienced by families, stress management strategies, stages of schizophrenia, side effects of medication, obtaining financial assistance, and other topics of interest.

What’s New

This module identified activities in the community or news items that were relevant to persons with schizophrenia and their support persons.

Data Collection and Analyses

Trained interviewers collected self-report data from participants at study entry (baseline) and at two subsequent assessment points (3 and 6 months postbaseline). Data collected from the support persons included their sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., age, gender, education); ratings of disease-related distress (Greenberg, Seltzer, & Greenley, 1993); and social support (Finch, Okun, Barrera, Zautra, & Reich, 1989; Krause & Markides, 1990; Lubben, 1988; Sherbourne & Stewart, 1991). Data collected from the persons with schizophrenia included sociodemographic characteristics (e.g., age, gender, education); self-rated stress; and social support (Finch et al., 1989; Krause & Markides, 1990; Lubben, 1988; Sherbourne & Stewart, 1991). Participants in the intervention condition provided their subjective evaluations of the Web site using the Website Evaluation Instrument (WEI; Rotondi, Sinkule, Balzer, & Harris, 2004). The WEI, which was developed from several standard instruments, was adjusted to contain items that covered specific components of this Web-based intervention. The WEI measured such characteristics as helpfulness, understandability, value, and ease of use, using a 5-point ordinal scale (1 = not at all, 2 = a little, 3 = moderately, 4 = very much, 5 = extremely). It included open-ended questions that solicited ideas for changes or additions to the Web site. Although the collection of longitudinal data is ongoing, baseline and 3-month data collection were completed and are reported here.

Several aspects of social support were assessed using available instruments: family and friend network sizes (Lubben, 1988); instrumental and tangible support (Krause & Markides, 1990; Sherbourne & Stewart, 1991); emotional and informational support (Krause & Markides, 1990; Sherbourne & Stewart, 1991) and satisfaction with each (Krause & Markides, 1990); positive social interactions (Sherbourne & Stewart, 1991); and negative interactions (Finch et al., 1989; Krause & Markides, 1990). For the analyses of social support presented here, only the 17 perceived emotional and informational support items were used, as these were the social support characteristics hypothesized to be influenced by the intervention, versus other components of social support (e.g., received instrumental or tangible support, family network size, or friend network size) that were not anticipated to be influenced by the intervention. Though it was expected that participants in the intervention group would have an increased number of people with whom they communicated owing to the online groups, and that they would receive emotional and informational support from these groups, there was little information to indicate whether people who participate in online groups consider their fellow participants, with whom they most likely do not have face-to-face relationships, to be “friends”; thus, an increase in friend network size was not hypothesized and not included in this analysis. The informational support and emotional support subscales of the instrument that was developed by Krause and Markides (1990) have both been shown to have high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alphas of .81 and .83, respectively) and have good predictive validity (shown to buffer the impact of bereavement on depressive symptoms).

Baseline Characteristics of the Sample

Three-month data were analyzed, employing intention-to-treat analyses. To identify differences between the persons with schizophrenia in the intervention and control groups on the measures of perceived social support and stress, analysis of covariance was used, including baseline data as a covariate. To identify differences between support persons in the intervention and control groups on the measures of perceived social support and disease-related distress, analysis of covariance was used, including baseline data as a covariate. Changes in the usage of the Web site and its components over time, by persons with schizophrenia or by family members, were analyzed by comparing Month 1 usage with Month 3 usage using a two-tailed Wilcoxon signed-ranks test.

Results

Use of the Schizophrenia Guide

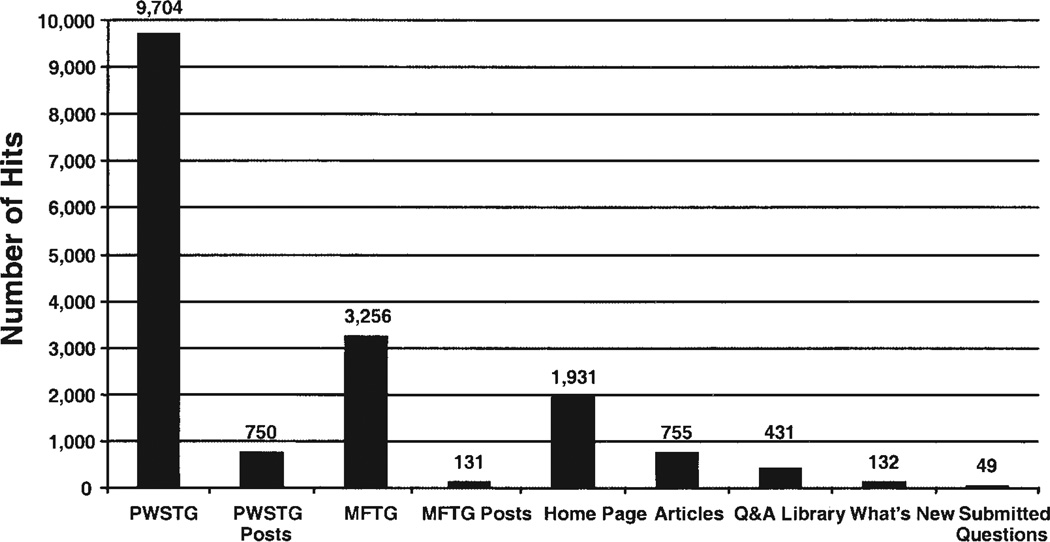

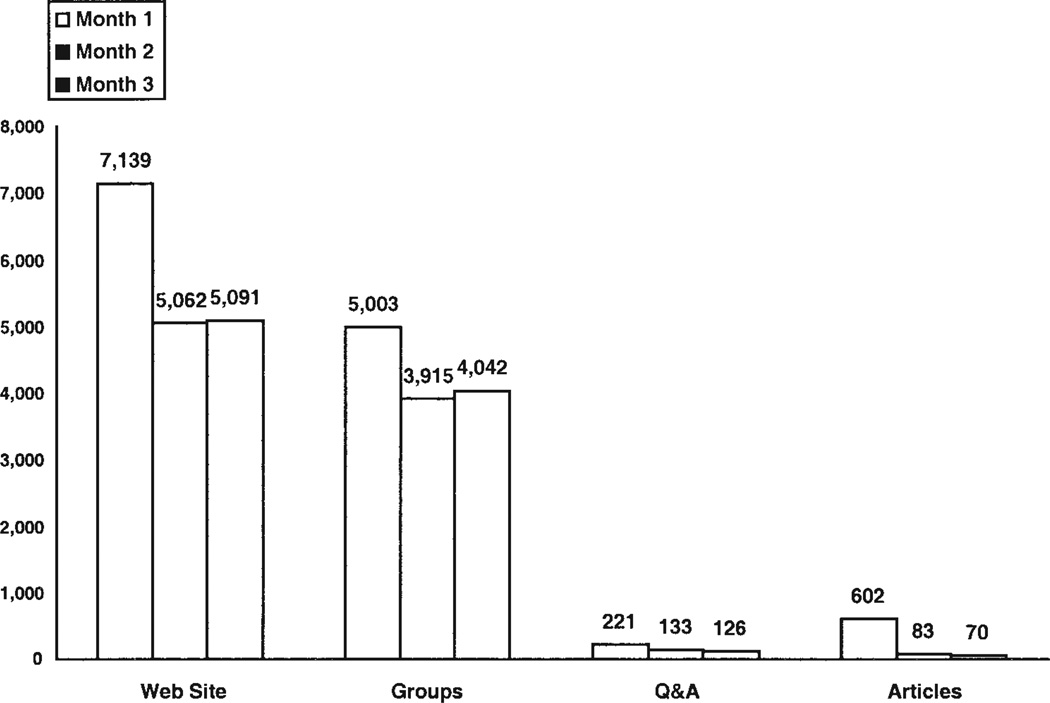

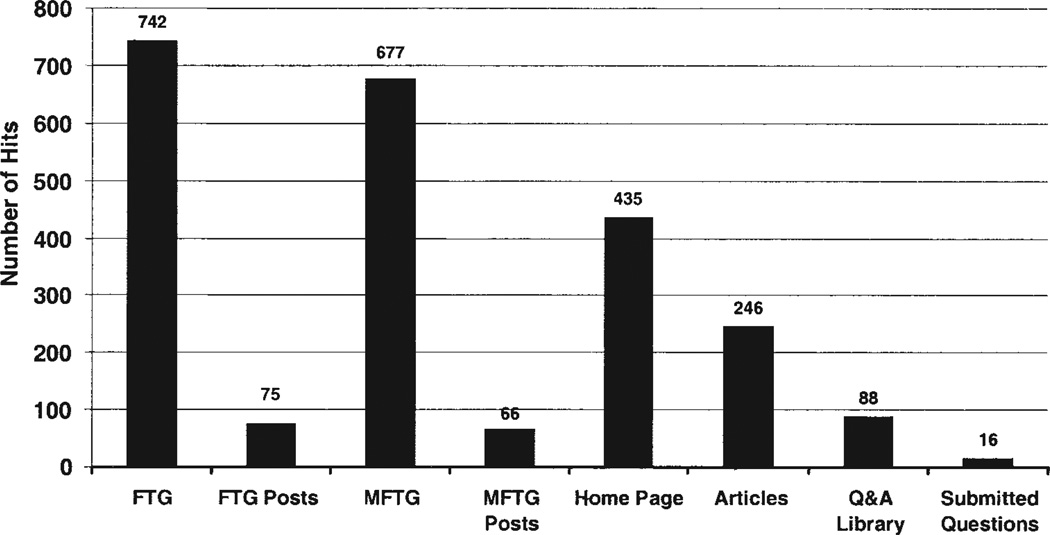

Persons with schizophrenia

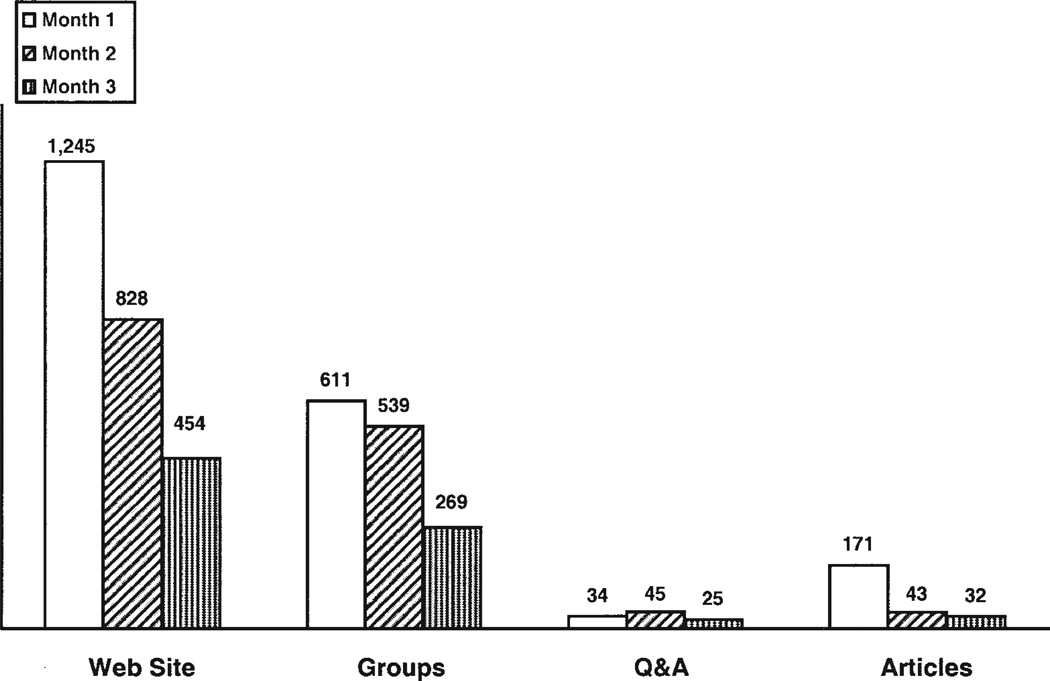

The total number of pages accessed (i.e., “hits”) on the Web site was 17,292 over the 3-month period of observation for persons with schizophrenia assigned to the intervention condition. The average number of hits per person for the 3-month period was 1,080.7 (SD = 1,812.0, range = 86–6,325). The most frequently used components of the site were the two therapy groups, with PWSTG being the most often used component (see Figure 3). The use of the site and its three main components varied over the 3 months (see Figure 4), dropping significantly between the first and third months for total Web site usage and Educational and Reading Materials, but not for the usage of the online therapy groups or the combined use of the Questions and Answers Library and Ask Our Experts Your Questions module (see Table 2).

Figure 3.

Persons with schizophrenia Web site usage by component. PWSTG = persons with schizophrenia therapy group; MFTG = multifamily therapy group; posts = messages posted on Web site; Q&A = Questions and Answers.

Figure 4.

Persons with schizophrenia Web site usage for Months 1, 2, and 3. Web site = total Web site hits; Groups = persons with schizophrenia therapy group and multifamily therapy group; Q&A = Questions and Answers Library and submitted questions; Articles = educational reading materials.

Table 2.

Means and Standard Deviations for Web Site Usage by Persons With Schizophrenia and Family Members

| Time |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month 1 |

Month 3 |

||||

| Web site component | M | SD | M | SD | Wilcoxon signed ranks test |

| Persons with schizophreniaa | |||||

| Education and reading materials | 37.6 | 53.7 | 4.4 | 4.1 | Z (−2.742), p= .006 |

| Combined PWSTG and MFTG | 312.7 | 605.9 | 252.6 | 470.1 | Z (−0.698), p= .458 |

| Combined Q&A Library and submitted questions | 13.8 | 28.6 | 7.9 | 11.9 | Z (−2.296), p= .195 |

| Web site total usage | 446.2 | 784.2 | 318.2 | 557.6 | Z (−2.172), p= .030 |

| Family members/support personsb | |||||

| Education and reading materials | 15.5 | 16.8 | 2.9 | 7.4 | Z (−2.627), p= .009 |

| Combined PWSTG and MFTG | 55.5 | 38.3 | 24.4 | 29.9 | Z (−2.312), p= .021 |

| Combined Q&A Library and submitted questions | 3.1 | 5.4 | 2.3 | 4.4 | Z (−0.339), p= .735 |

| Web site total usage | 113.2 | 75.6 | 41.3 | 39.7 | Z (−2.845), p= .004 |

Note. Wilcoxon signed ranks test, based on positive ranks. PWSTG = persons with schizophrenia therapy group; MFTG = multifamily therapy group; Q&A = Questions and Answers.

n= 16.

n= 11.

Family/support persons

Family members and support persons recorded a total of 2,527 hits, with an average per person of 229.7 (SD = 164.5, range = 55–362; see Figure 5). The most frequently used components were the two therapy groups. Usage of the Web site and its components varied over the first 3 months (see Figure 6). Usage dropped significantly between the first and third months in a fashion identical to that of the persons with schizophrenia (see Table 2).

Figure 5.

Family/support person Web site usage by component. FTG = family/support person therapy group; posts = messages posted on Web site; MFTG = multifamily therapy group.

Figure 6.

Family/support person Web site usage for Months 1, 2, and 3. Web site = total Web site hits; Groups = family member therapy group and multifamily therapy group; Q&A = Questions and Answers Library and submitted questions; Articles = educational reading materials.

Outcomes

When compared with the control group, persons with schizophrenia in the telehealth group had significantly less perceived stress and showed a trend toward greater perceived social support (see Table 3). There were no significant differences in outcome variables between the support persons in the telehealth and usual care groups (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Means, Standard Deviations, and Outcome Analyses for Persons With Schizophrenia and Family Members

| Time |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline |

3 months |

||||||||

| TAU |

TELE |

TAU |

TELE |

||||||

| Measure | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | ANCOVA |

| Persons with schizophreniaa | |||||||||

| Perceived social support | 1.61 | 0.91 | 1.88 | 0.44 | 1.54 | 0.60 | 1.96 | 0.43 | F(1, 27) = 3.79, p= .062 |

| Perceived stress | 2.13 | 0.46 | 1.82 | 0.52 | 2.15 | 0.63 | 1.64 | 0.41 | F(1, 27) = 4.47, p= .044 |

| Family members/support personsb | |||||||||

| Perceived social support | 1.25 | 0.52 | 1.66 | 0.64 | 1.20 | 0.75 | 1.64 | 0.90 | F(1, 18) = 0.36 |

| Perceived stress | 1.77 | 0.78 | 1.63 | 0.69 | 1.85 | 0.83 | 1.53 | 0.77 | F(1, 18) = 0.64 |

Note. TAU = treatment as usual; TELE = telehealth intervention; ANCOVA = analysis of covariance (for which only F tests for Intervention Group × Time interactions are presented)

n = 14 for TAU; n= 16 for TELE.

n = 10 for TAU; n= 11 for TELE.

Participants’ Evaluations of the Web Site

Persons with schizophrenia

Participants were asked to make several subjective evaluations about the Web site (see Table 4). Nearly half of the participants with schizophrenia reported feeling some level of stress (44.7%), and 18.8% reported feeling a little loneliness while using the site. The ratings of the ease of use of the site and its components indicated that some users did have difficulty with the technology. The highest rating of difficulty (not at all easy) was given by 6.3% of participants for three of the components (MFTG, Articles, and What’s New) but not the others (PWSTG, Ask Our Experts Your Questions, Questions and Answers Library). Most (68.8% to 81.4%) participants found the Web site and its components moderately to extremely easy to use. Although 12.6% of participants indicated that the arrangement of information on the screen rarely or sometimes made sense, 87.6% of participants indicated that the arrangement often or always made sense.

Table 4.

Subjective Evaluations (in Percentages) of the Schizophrenia Guide by Persons With Schizophrenia

| Emotion or component |

Not at all |

A little |

Moderately | Very much |

Extremely |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotions experienced while using the Schizophrenia Guide | |||||

| Loneliness | 81.3 | 18.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Stress | 56.3 | 12.5 | 12.5 | 18.8 | 0 |

| Ease of use of the Schizophrenia Guide and its components | |||||

| Website overall | 6.3 | 25.0 | 0 | 37.5 | 31.3 |

| PWSTG | 0 | 18.8 | 12.5 | 37.5 | 31.3 |

| MFTG | 6.3 | 12.5 | 18.8 | 56.3 | 6.3 |

| Ask an Expert | 0 | 25.0 | 6.3 | 37.5 | 31.3 |

| Questions and Answers Library |

0 | 31.3 | 6.3 | 37.5 | 25.0 |

| Articles | 6.3 | 12.5 | 18.8 | 43.8 | 18.8 |

| What’s New | 6.3 | 18.8 | 12.5 | 43.8 | 18.8 |

| Value of the Schizophrenia Guide and its components | |||||

| Website overall | 0 | 0 | 6.3 | 56.3 | 37.5 |

| PWSTG | 0 | 0 | 6.3 | 50.0 | 43.8 |

| MFTG | 0 | 18.8 | 12.5 | 43.8 | 25.0 |

| Ask an Expert | 0 | 0 | 25.0 | 50.0 | 25.0 |

| Questions and Answers Library |

0 | 12.5 | 25.0 | 37.5 | 25.0 |

| Articles | 0 | 18.8 | 18.8 | 43.8 | 18.8 |

| What’s New | 6.3 | 18.8 | 12.5 | 43.8 | 18.8 |

| Did the arrangement of information on the screen make sense? | |||||

| Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Often | Always | |

| Overall | 0.0 | 6.3 | 6.3 | 31.3 | 56.3 |

Note. PWSTG = persons with schizophrenia therapy group; MFTG = multifamily therapy group.

Participants also rated the “value” of the Web site and its components. Only the What’s New component of the site was endorsed at the lowest value rating (6.3%). The PWSTG received the highest value rating (extremely valuable) from the largest proportion (43.8%) of participants, whereas the Articles received the highest value rating from the lowest proportion (18.8%) of participants. Though the smallest proportion found the Articles to be extremely valuable, 81.4% of participants rated the Articles as moderately to extremely valuable. When asked whether they would like to be involved in the PWSTG if it was offered after the study was concluded, 93.8% answered yes.

Family members/support persons

Support persons in the intervention group were also asked to make subjective evaluations about the Web site (see Table 5). Some participants reported feeling a little (9.1%) or moderate (9.1%) stress and reported feeling a little (9.1%) or moderate (18.2%) loneliness while using the Web site. Although participants’ ratings of the ease of use varied, no component received the highest rating of difficulty (not at all easy), and 9.1% of participants rated three components (FTG, Questions and Answers Library, and What’s New) at the next level of difficulty (a little easy). The Web Site Overall, MFTG, Ask Our Experts Your Questions, and Articles were rated by all participants as moderately to extremely easy to use. When asked to rate whether the arrangement of information on the screens made sense, 36.4% indicated never or rarely.

Table 5.

Subjective Evaluations (in Percentages) of the Schizophrenia Guide by Family/Support Persons

| Emotion or component | Not at all |

A little |

Moderately | Very much |

Extremely |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Emotions experienced while using the Schizophrenia Guide | |||||

| Loneliness | 63.6 | 9.1 | 18.2 | 0 | 0 |

| Stress | 72.7 | 9.1 | 9.1 | 0 | 0 |

| Ease of use of the Schizophrenia Guide and its components | |||||

| Website overall | 0 | 0 | 45.5 | 18.2 | 27.3 |

| FTG | 0 | 9.1 | 18.2 | 36.4 | 27.3 |

| MFTG | 0 | 0 | 27.3 | 45.5 | 18.2 |

| Ask an Expert | 0 | 0 | 36.4 | 36.4 | 18.2 |

| Questions & Answers Library 0 | 9.1 | 36.4 | 27.3 | 18.2 | |

| Articles | 0 | 0 | 27.3 | 36.4 | 27.3 |

| What’s New | 0 | 9.1 | 18.2 | 36.4 | 27.3 |

| Value of the Schizophrenia Guide and its components | |||||

| Website overall | 0 | 9.1 | 0 | 45.5 | 36.4 |

| FTG | 0 | 0 | 9.1 | 54.5 | 27.3 |

| MFTG | 0 | 0 | 18.2 | 45.5 | 27.3 |

| Ask an Expert | 0 | 9.1 | 0 | 45.5 | 36.4 |

| Questions & Answers Library 0 | 9.1 | 9.1 | 45.5 | 27.3 | |

| Articles | 0 | 0 | 9.1 | 45.5 | 36.4 |

| What’s New | 0 | 9.1 | 9.1 | 36.4 | 36.4 |

| Did arrangement of information on the screen make sense? | |||||

| Never | Rarely | Sometimes | Often | Always | |

| Overall | 27.3 | 9.1 | 9.1 | 18.2 | 27.3 |

Note. FTG = family therapy group; MFTG = multifamily therapy group.

All participants rated the FTG, MFTG, and Articles as moderately to extremely valuable. No component received the lowest rating of value (not at all valuable). Nearly all participants (90.9%) indicated that they would like to be involved in the FTG if it was offered after the study was concluded.

Suggested changes to the Web site

To help participants familiarize themselves with the other members of the online groups, persons with schizophrenia suggested, a biographical sketch for each participant could be added, including his or her picture. It was suggested that Web cams could be added so that participants would be able to see and talk with each other in real time. Another suggestion was that notices for non-mental-health related community events be added to the Web site. For the Questions and Answers Library, one participant stated that “because I cannot always think [of] what to ask,” it would be helpful if common questions could be anticipated and their answers provided.

Support persons also made these last two suggestions. Also, in the What’s New section of the Web site, they wanted to see more information on the latest developments on medications and other research to treat schizophrenia. Finally, there was a desire to have a section of the Web site where family members could share non-illness-related items of interest, such as cooking recipes.

Discussion

After 3 months, persons with schizophrenia who were engaged in the experimental telehealth intervention had a greater reduction in stress than their counterparts in the usual care group, as well as a trend to higher perceived social support. The Web site usage data indicated that persons with schizophrenia can and will use a text-based telehealth application to receive psychosocial treatments, to obtain education about the illness, and to participate in group and multifamily therapy. The persons with schizophrenia group used the telehealth intervention more than did the support persons group. No differences in outcomes were found for support persons in the intervention group when compared with the usual care group.

The persons with schizophrenia group had nearly seven times as many hits to the Web site as did the support persons group. Given the cognitive deficits inherent in the illness, we hypothesized that the persons with schizophrenia group would use the site less than would the support persons group. That the opposite occurred is an indication that this type of telehealth intervention will be used by, and will be useful to, persons with schizophrenia. Moreover, it indicates that telehealth-based access to services may improve the delivery of services to persons with schizophrenia and thus lead to better clinical outcomes.

The greater use of the Web site by the persons with schizophrenia group may indicate that the reduction in perceived stress was more a direct effect of the intervention than the indirect effect caused by the intervention on families and other support persons (see Figure 1). Although the inclusion in our sample of persons with schizophrenia with nonfamilial or no support persons could have helped to identify a direct effect or a nonfamilial effect, the size of the sample did not permit these analyses.

Web Site Usage

In addition to differences in usage between the persons with schizophrenia and the support persons, there were also clear interindividual differences. However, it is not clear how to interpret such usage differences. There is not a theoretical or clinical basis (of which we are aware) that would suggest that the same usage by different individuals should produce the same effects, or that usage should be directly comparable between individuals in terms of its effects. Different people will likely need different amounts of usage to produce similar effects, and the amount of usage needed to produce an effect may vary depending on individual characteristics, such as needs and symptom severity. Indeed, knowledge of the processes of psychosocial interventions would suggest that such differences are highly likely. For those who have few needs or symptoms, it may be that no amount of usage will produce a detectable effect. A few examples help to illustrate this point.

Informal feedback from a person with schizophrenia who was an infrequent user indicated that she considered the Web site to be very important to her well-being. Though not often used, it was a resource that she knew was there and to which she could turn when the need arose. Thus, she felt it reduced her distress. Another person with schizophrenia, one who rarely entered the Web site, posted an important personal problem she was having after not having used the site for more than a month. It may be that some users are influenced by the mere availability of these types of services, a belief that it will be helpful if a need arises, and will turn to it on an as-needed basis.

It is likely that there will be individual differences in the amount and types of intervention usage needed to influence outcomes. Individual or group comparisons of the amount or type of intervention usage may provide little insight until they can be explored using modeling that links usage and individual characteristics to outcomes.

Usability of Web-Based Resources

A significant amount of conceptual modeling and usability testing was performed to develop a design for the Web site that would accommodate persons who had serious mental illness (SMI) and cognitive deficits (Rotondi, Sinkule, Haas, et al., 2004). Due, in part, to the cognitive deficits associated with schizophrenia, reading materials are not typically emphasized as a format for information and education. Thus, a component of the design work and usability testing focused on making the educational reading materials more accessible to persons with schizophrenia. Materials on the Web site were specifically tailored for this audience on the basis of the results of our usability testing.

An additional obstacle to the reliance on reading materials as a source for information is that there are probably very few public libraries that contain materials on these topics, and university medical libraries—which contain source materials that cover some of the medical topics—may be quite intimidating, may not encourage public use, and may contain only technical materials designed for medical practitioners and academics rather than consumers. Thus, although persons with schizophrenia may not routinely obtain information and education through reading, one obstacle to their use may be the difficulties of accessing relevant and less technical reading materials. This is compounded for those persons with schizophrenia, who may have difficulties traveling to and negotiating community resources.

The data presented here show that with adaptations to compensate for cognitive limitations and to overcome barriers to accessibility, persons with schizophrenia will use text-based educational materials. Our experience suggests that several aspects of the Web site materials may have made them particularly appealing to users: (a) The written educational materials were presented in a two-tiered format, where the first one or two paragraphs summarized the information in the article and were written at a relatively low reading level; (b) content focused on issues that our needs assessment indicated were particularly relevant to the day-to-day problems faced by persons with schizophrenia and their support persons; (c) access was provided to up-to-date medical information written in relatively nontechnical language; and (d) users were not required to travel to a library or search through book stacks to obtain the materials. Thus, online resources help overcome some of the obstacles to use of written materials by persons with schizophrenia.

Nonetheless, designing comprehensible materials and a user-friendly Web site are still significant challenges. The stress reported by some individuals with schizophrenia while using the site may have been caused, at least in part, by difficulty with the technology and the design of the site. Consistent with this interpretation were the relatively low ratings of the Web site’s ease of use by some persons with schizophrenia. This suggests that additional design work needs to be conducted to better accommodate persons with SMI and cognitive deficits.

During the design phase, it was assumed that a Web site designed to accommodate persons with cognitive deficits would meet the needs of individuals who do not have such cognitive deficits and/or do not have schizophrenia. Therefore, much less prestudy design work was conducted with non-SMI individuals. Even though a few of the persons with schizophrenia indicated that they had difficulty using the technology, most found that the arrangement of information on the Web site made sense. Support persons generally rated the site as easier to use than did persons with schizophrenia, but they were less satisfied with the arrangement of information on the Web pages. Taken together, these findings may indicate that Web site designs that facilitate use by persons with SMI and/or cognitive deficits may not be as satisfying to other non-SMI users.

Deviations From a Traditional Psychoeducational Model

Many persons with schizophrenia have limited or no contact with their families and may have few friends or support persons other than paid health care professionals. In recognition of the difficulty that treatment centers may have contacting family members or funding psychoeducational services to family members, even those who would like to participate, the social isolation of many persons with schizophrenia, and the chronic nature of the illness, this project deviated from a traditional psychoeducational model in three ways. First, it admitted persons with schizophrenia who were not recovering from an acute episode. Second, it included persons with schizophrenia without a family member but with an informal support person (e.g., a friend) who was willing to participate. Third, it included persons with schizophrenia on their own, that is, those who did not have a family member or an informal support person who would join with them. Although some formal programs provide psychoeducation to family members only, that is, without the involvement of persons with schizophrenia (National Alliance for the Mentally Ill, 2004), we are not aware of any published research regarding psychoeducational programs provided to persons with schizophrenia and their friends, or to persons with schizophrenia only. These deviations from the traditional psychoeducational model allowed us to offer the telehealth psychoeducational services to a broader segment of the population of persons with schizophrenia than would otherwise have occurred, but the sample was not large enough for us to compare results across subgroups.

Study Limitations

Conclusions from this report should be considered provisional because of the relatively small size of the sample, because the intervention is still evolving, and because of the limited duration of the follow-up period. In addition, the demographic composition of the relatively small sample, in terms of ethnicity and gender, might have influenced the results. Although findings from this study are promising with regard to the usability of Web-based telehealth interventions in schizophrenia, the potential complexity of Web-based materials remains an important obstacle to their wider utilization. Given that significant cognitive deficits are characteristic of many individuals with schizophrenia, there is a need for further research on and development of accessible interfaces for persons with SMI. Another potential obstacle to widespread use of such interventions is a lack of individual access to the necessary technology, including a computer and Internet services. Limited financial resources, as well as cognitive and other difficulties that limit everyday instrumental functioning (e.g., adequate knowledge for purchase and set-up of computer equipment), are also likely to continue to restrict use of Internet-based interventions by some individuals with SMI. Therefore, enhanced access to technologies that are not only available but user friendly will require further development before telehealth applications can become widespread.

Telehealth interventions of the type presented here have two important restrictions. The first is that professional mental health therapists must contend with the geographic restrictions of licenses to practice, which are specific to each state. Thus, though the technology can reduce geographic impediments to treatment, therapists who monitor and/or facilitate online clinical interventions must be licensed in each of the states where participants reside. A second restriction involves the confidentiality of communications to the Web site. Despite the built-in measures that were taken in this study to maintain the security of the site and the confidentiality of its contents, such efforts may not always succeed. This potential risk to the privacy of the individual and the confidentiality of the material that is shared by participants should be clearly explained to all at the outset. They should also be told that although efforts are made to guard against inappropriate postings, there may be occasions when personal interpretations of the intended meaning of written communications result in personal discomfort. The involvement of online clinician monitors or facilitators is an important and necessary safeguard against personal risks. The integration of these clinician-based services presents a necessary additional measure of complexity to the dissemination of Internet-based interventions.

Conclusions

The Schizophrenia Guide is one of the first telehealth applications to provide treatment services to persons with schizophrenia and their support persons in their homes. It is also one of the first such applications to provide group and multifamily therapy online. Few families of persons with schizophrenia receive any services despite their proven efficacy (Lehman & Steinwachs, 1998b). Moreover, only one out of two people with SMI seeks treatment for the disorder (Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2002; Farmer, Mustillo, Burns, & Costello, 2003; Kessler et al., 2001). Thus, there is considerable potential value in telehealth applications for delivery of these services to persons with schizophrenia and their support persons. The findings of this study suggest that (a) such services can and will be used by individuals with schizophrenia and their support persons and (b) use of telehealth services is associated with reduced perceived stress among persons who have schizophrenia. The provision of Internet and telehealth interventions has the potential to increase access to psychosocial services for persons with schizophrenia, as well as others with SMI, and their families and support persons. To date, there has been a dearth of research on the development of Web site designs accessible to persons with SMI and cognitive deficits. The promising nature of these early findings suggests that there is a need for such research, as well as research to demonstrate the efficacy of telehealth applications and to demonstrate their potential for successful dissemination to the broader community.

Acknowledgments

This project was supported by Grant R01 MH63484 from the National Institute of Mental Health.

Contributor Information

A. J. Rotondi, Department of Critical Care Medicine, School of Medicine, University of Pittsburgh, and Department of Health Policy and Management, Graduate School of Public Health, University of Pittsburgh

G. L. Haas, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh

C. M. Anderson, Department of Psychiatry and Department of Social Work, University of Pittsburgh

C. E. Newhill, Department of Social Work, University of Pittsburgh

M. B. Spring, Department of Information Sciences, University of Pittsburgh

R. Ganguli, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh

W. B. Gardner, Children’s Research Institute, Columbus, Ohio, and Department of Pediatrics, Ohio State University

J. B. Rosenstock, Department of Psychiatry, University of Pittsburgh

References

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: Author; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson CV, Reiss DJ, Hogarty GE. Schizophrenia and the family: A practitioner’s guide to psychoeducation and management. New York: Guilford Press; 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Anderson J, Adams C. Family interventions in schizophrenia. British Medical Journal. 1996;313:505–506. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7056.505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrowclough C, Tarrier N. Families of schizophrenic patients, cognitive behavioural intervention. London: Chapman & Hall; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Burns T. Psychosocial interventions. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 1997;10:36–39. [Google Scholar]

- Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. National Household Survey on Drug Abuse: Volume I. Summary of national findings: Prevalence and treatment of mental health problems. Washington, DC: Author; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer EMZ, Mustillo S, Burns BJ, Costello EJ. The epidemiology of mental health programs and service use in youth: Results from the Great Smoky Mountains Study. In: Epstein MH, Kutash K, Duchnowsk A, editors. Outcomes for children and youth with behavioral and emotional disorders and their families: Programs and evaluation best practice. 2nd ed. Austin, TX: Pro-Ed; 2003. pp. 23–44. [Google Scholar]

- Finch JF, Okun MA, Barrera M, Jr, Zautra AJ, Reich JW. Positive and negative social ties among older adults: Measurement models and the prediction of psychological distress and well-being. American Journal of Community Psychology. 1989;17:585–605. doi: 10.1007/BF00922637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein MJ, Roderick EH, Evans JR, May PRA, Steinberg JR. Drug and family therapy in the aftercare treatment of acute schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1978;35:1169–1177. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1978.01770340019001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graber MA, Roller CM, Kaeble B. Readability levels of patient education material on the World Wide Web. Journal of Family Practice. 1999;48:58–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg JS, Seltzer MM, Greenley JR. Aging parents of adults with disabilities: The gratifications and frustrations of later-life caregiving. Gerontologist. 1993;33:542–550. doi: 10.1093/geront/33.4.542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hazel NA, McDonell MG, Short RA, Berry CM, Voss WD, Rodgers ML, et al. Impact of multiple-family groups for outpatients with schizophrenia on caregivers’ distress and resources. Psychiatric Services. 2004;55:35–41. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.1.35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyman S. Schizophrenia: Understanding it, treating it, living with it; Washington, DC. Presented at the NIMH and the Library of Congress Project on the Decade of the Brain Congressional Breakfast.Sep, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Berglund PA, Bruce ML, Koch JR, Laska EM, Leaf PJ. The prevalence and correlates of untreated serious mental illness (Rep. No. 36) Health Services Research. 2001;36:987–1007. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krause N, Markides K. Measuring social support among older adults. International Journal of Aging and Human Development. 1990;30:37–53. doi: 10.2190/CY26-XCKW-WY1V-VGK3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leff J, Berkowitz R, Shavit N, Strachan A, Glass I, Vaughn C. A trial of family therapy v. a relatives group for schizophrenia. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1989;154:58–66. doi: 10.1192/bjp.154.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM. Patterns of usual care for schizophrenia: Initial results from the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) Client Survey. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1998a;24:11–20. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman AF, Steinwachs DM. Translating research into practice: The Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) treatment recommendations. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1998b;24:1–10. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lubben JE. Assessing social networks among elderly populations. Family Community Health. 1988;11:42–52. [Google Scholar]

- Mari JJ, Streiner DL. An overview of family interventions and relapse on schizophrenia: Meta-analysis of research findings. Psychological Medicine. 1994;24:565–578. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700027720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall M. Case management: A dubious practice. British Medical Journal. 1996;312:523–524. doi: 10.1136/bmj.312.7030.523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFarlane W, Deakins S, Gingerich SL, Dunne E, Horen B, Newmark M. Multiple-Family Psychoeducational Group Treatment Manual. New York: Biosocial Treatment Division, New York State Psychiatric Institute; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- National Alliance for the Mentally Ill. Family-to-Family Education Program. 2004 Retrieved September 10, 2004, from http://www.nami.org/Template.cfm?Section=Family-to-Family.

- National Institute of Mental Health. The numbers count: Mental illness in America. 1999 Retrieved September 10, 2004, from http://www.nami.org/Template.cfm?Section=Family-to-Family.

- Nuechterlein KH, Dawson ME, Gitlin M, Ventura J, Goldstein MJ, Snyder KS, et al. Developmental processes in schizophrenic disorders: Longitudinal studies of vulnerability and stress. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1992;18:387–425. doi: 10.1093/schbul/18.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rotondi AJ, Sinkule J, Balzer K, Harris J. Understanding the needs of those who have experienced a traumatic brain injury and their primary family caregivers: A first step toward improving service delivery and outcomes. 2004 Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Rotondi AJ, Sinkule J, Balzer K, Harris J, Moldovan R. A statewide assessment of the needs of those who have experienced a traumatic brain injury and their family members. Harrisburg: Pennsylvania Department of Health; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rotondi AJ, Sinkule J, Haas G, Litschge C, Spring M, Anderson C, et al. Design and usability performance of a telehealth psychoeducation intervention for persons with schizophrenia and their families. 2004 Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Rotondi AJ, Sinkule J, Spring M. An interactive Web-based intervention for persons with TBI and their families: Use and evaluation by female significant others. Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 2005;20:173–185. doi: 10.1097/00001199-200503000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherbourne CD, Stewart AL. The MOS social support survey. Social Science Medicine. 1991;32:705–714. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(91)90150-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. Family interventions: Service implications. In: Birch-wood M, Tarrier N, editors. Innovations in the psychological management of schizophrenia. Chichester, England: Wiley; 1992. pp. 235–251. [Google Scholar]

- Szmukler GI, Herrman H, Colusa S, Benson A, Bloch S. A controlled trial of a counselling intervention for caregivers of relatives with schizophrenia. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 1996;31:149–155. doi: 10.1007/BF00785761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarrier N, Barrowclough C, Vaughn C, Bamrah JS, Porceddu K, Watts S, et al. The community management of schizophrenia: A controlled trial of a behavioural intervention with families to reduce relapse. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1988;153:532–542. doi: 10.1192/bjp.153.4.532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zubin J, Spring B. Vulnerability: A new view of schizophrenia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 1977;86:103–126. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.86.2.103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]