Abstract

Natural killer T cells (NKT cells) are comprised of several subsets. However, the possible differences in their developmental mechanisms have not been fully investigated. To evaluate the dependence of some NKT subpopulations on nuclear factor-κB-inducing kinase (NIK) for their generation, we analysed the differentiation of NKT cells, dividing them into subsets in various tissues of alymphoplasia (aly/aly), a mutant mouse strain that lacks functional NIK. The results indicated that the efficient differentiation of both invariant NKT (iNKT) and non-iNKT cells relied on NIK expression in non-haematopoietic cells; however, the dependence of non-iNKT cells was lower than that of iNKT cells. Especially, the differentiation of CD8+ non-iNKT cells was markedly resistant to the aly mutation. The proportion of two other NKT cell subsets, NK1.1+ γδ T cells and NK1.1− iNKT cells, was also significantly reduced in aly/aly mice, and this defect in their development was reversed in wild-type host mice given aly/aly bone marrow cells. In exerting effector functions, NIK in NKT-αβ cells appeared dispensable, as NIK-deficient NKT-αβ cells could secrete interleukin-4 or interferon-γ and exhibit cytolytic activity at a level comparable to that of aly/+ NKT-αβ cells. Collectively, these results imply that the NIK in thymic stroma may be critically involved in the differentiation of most NKT cell subsets (although the level of NIK dependence may vary among the subsets), and also that NIK in NKT-αβ cells may be dispensable for their effector function.

Keywords: differentiation, nuclear factor-κB-inducing kinase, natural killer T cells

Introduction

Accumulating studies have shown that natural killer T (NKT) cells are important in the regulation of various types of immune responses. They play crucial and diverse roles in the control of both innate and adaptive immune responses, upon activation by recognizing lipid antigen presented on class Ib MHC molecules such as CD1d.1

The NKT cells are heterogeneous populations, many of which are restricted by CD1d. The CD1d-restricted NKT-αβ cells can be divided into two subpopulations, type I and type II NKT cells, based on the T-cell receptor (TCR) repertoire or the type of recognized antigens. The type I NKT cells, or invariant NKT (iNKT) cells, express invariant TCR-α chain associated with a limited repertoire of TCR-β chain, whereas type II NKT cells express more diverse sets of TCR-α and TCR-β chains.2 The NKT-αβ cells can be further segregated into subsets by the expression of cell surface molecules including co-receptors. Most iNKT cells are known to be either CD4+ or CD4/CD8 double-negative (DN), and non-iNKT cells contain CD8+ cells in addition to those two subsets (non-invariant NKT-αβ cells are hereafter referred to as non-iNKT cells). Phenotypic classification of iNKT cells by some cell surface molecules is often associated with their functions,3–5 though it is not clear whether such associations exist in type II NKT or in other CD1d-independent NKT-αβ cells. The functional contributions of these discrete subsets to each aspect of various immune responses, such as autoimmunity, infection and inflammation, have not been thoroughly assessed. Also, it is not known how each subset of NKT cells differentiates from common precursor cells in the thymus.6,7

Although most NKT-αβ cells differentiate in the thymus like conventional T cells through the process of positive selection depending on the TCR signalling, the developmental requirements of NKT-αβ cells differ substantially from those of conventional T cells.6 Analyses of various gene-targeted mutant mice identified several molecules as being essential specifically for the differentiation of NKT-αβ cells but not for conventional T cells.6 One example is nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB) -inducing kinase (NIK), which is an important kinase predominantly involved in the non-canonical pathway of NF-κB activation.8,9 We and others previously demonstrated that the systemic absence of functional NIK, as in NIK knockout or in a spontaneous NIK mutant mouse, alymphoplasia,10,11 resulted in impairment of NKT-αβ cell generation, whereas conventional T cells develop in normal numbers.12–14 Interestingly, analyses of bone marrow (BM) chimera demonstrated that the differentiation defect of NKT-αβ cells in NIK-impaired mice could be attributed to host cells rather than donor cells, indicating the T-cell-extrinsic role of NIK for NKT-αβ cell generation.12–14 The deficiency of NKT-αβ cell generation in aly/aly mice was suggested to be caused by impaired formation of medullary thymic epithelial cells.15 However, although critical dependence on NIK of iNKT cell generation was clearly shown,13,14 the differentiation of other NKT subsets in the absence of NIK has yet to be investigated.

In addition, the necessity of NIK for NKT-αβ cells to exert their effector function has not been addressed, regardless of the facts that NIK is involved in TCR signalling and that some function was altered in conventional CD4+ αβ T cells lacking functional NIK.16–21 The NIK in γδ T cells may also have impact on their cellular action, because as we recently showed, interferon-γ (IFN-γ) production from γδ T cells in aly/aly mouse was significantly decreased, compared with that in the aly/+ mouse.22 These results raised a possibility that the functionality of mature NKT-αβ cells may also be affected by the absence of NIK.

In the current study, the development of NKT cell subsets in the aly/aly mouse was investigated to compare their dependence on NIK for their differentiation. Whether NIK in mature NKT-αβ cells plays any role in exhibiting their effector function was also examined. The results indicated that non-iNKT cells, especially CD8+ NKT-αβ cells, were significantly more resistant than iNKT cells, to the lack of NIK activity during their differentiation. It was also demonstrated that the optimal development of NKT-γδ cells, in a manner similar to that of NKT-αβ cells, demanded functional NIK in non-haematopoietic cells. Regarding the role of NIK in mature NKT-αβ cell functions, NIK was not an absolute requirement for cytokine production or for cytolysis. These results implied that among NKT cell subsets, distinct developmental programmes might be employed and that the TCR signal transduction cascades in NKT-αβ cells might be different from conventional αβ T cells or γδ T cells.

Materials and methods

Mice

The C57BL/6J (H-2b) mice were purchased from Charles River Japan, Inc. (Kanagawa, Japan). The alymphoplasia mice10 were initially obtained from CLEA Japan, Inc. (Tokyo, Japan), and mice bred onto C57BL/6J > 10 times were used in this study. MR1−/−23 or RAG-2−/−24 mice were kindly provided by Dr Susan Gilfillan (Department of Pathology and Immunology, Washington University School of Medicine, St Louis, MO) or Dr Yoichi Shinkai (Riken, Advanced Science Institute, Wako, Japan), respectively. The mice were used at 2–4 months of age. All mice used in this study were maintained in a specific pathogen-free facility at the Kitasato University School of Medicine. The Animal Experimentation and Ethics Committee of the Kitasato University School of Medicine approved experimental procedures, and all animal experiments were performed following the guidelines of the committee.

Lymphocyte preparation from tissues

Suspensions of cells from spleen, peripheral blood, or BM were prepared by removing red blood cells with Lymphosepar II (IBL, Gunma, Japan), or ammonium chloride–Tris buffer. To collect leucocytes from lung or liver, the tissues were ground on a 40-μm cell strainer (Corning, Corning, NY) using a syringe plunger in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium with 5% fetal calf serum, and the lymphocyte fraction separated over Lymphosepar II was harvested. Single-cell suspensions of thymocytes were prepared by gentle grinding of thymi with frosted glass slides (Matsunami Glass Ind., Osaka, Japan).

Antibodies and reagents

FITC-labelled or phycoerythrin (PE)-labelled antibodies to CD8 antibody (53-6.7), or CD3 (2C11) were purchased from BD BioSciences (San Diego, CA). Allophycocyanin-labelled NK1.1 (PK136), and CD3 (2C11) were from eBioscience (San Jose, CA). PE/Cy7-labelled anti-TCR-αβ (H57), or anti-CD326 (G8.8), PE-labelled TCR-γδ (GL3), Alexa Fluor 647-labelled Ly51 (6C3), PerCP/Cy5.5-labelled anti-IA/IE (M5/114), FITC-labelled anti-Vγ1.1 (2.11) or anti-Vγ2 (UC3-10A6), and allophycocyanin/Cy7-labelled anti-CD4 (GK1.5), were obtained from BioLegend (San Diego, CA). FITC-labelled Ulex Europaeus agglutinin (UEA-1) was purchased from Vector Laboratories, Inc. (Burlingame, CA). Type I iNKT cells were detected with α-galactosylceramide (α-GalCer)-loaded CD1d-dimeric immunoglobulin-fusion protein (BD Biosciences) and PE-labelled anti-mouse IgG1 (BD Biosciences, Mountain View, CA). The non-labelled antibodies to CD3ε (2C11) and to FcγR II/III (2.4G2) were prepared from culture supernatants of respective hybridomas in the laboratory.

Flow cytometric analyses and cell sorting

Around 1 million cells were stained in 2.4G2 culture supernatants, containing a predetermined concentration of fluorescence-labelled antibodies. After 30 min of incubation on ice, the cells were washed with ice-cold Hanks’ balanced salt solution containing 0·5% BSA and 0·02% sodium azide. Washed cells were analysed or sorted by FACSAria (BD Biosciences), and the acquired events were analysed with FlowJo software. Dead cells stained with 7-aminoactinomycin D (BioLegend, San Diego, CA) were gated out in the analyses.

Construction of irradiation BM chimeras

Irradiation BM chimeras were prepared as previously described.21 Briefly, lethally irradiated (8·5 Gy) RAG-2−/− mice of B6 background were injected intravenously with 1·0 × 107 BM cells from aly/aly or aly/+ mice. The recipient mice were analysed more than 8 weeks after transfusion.

Isolation of epithelial cells from the thymus

Thymic epithelial cells (TECs) were prepared as described in a previous study25 by Xing and Hogquist with a slight modification. Briefly, thymi from aly/aly or aly/+ mice, aged 6–12 weeks, were treated with 0·05% (weight/volume) Liberase TH and 100 U/ml DNase I (Roche Diagnostics, Indianapolis, IN) to release epithelial cells from the thymi in the medium. The anti-Thy1.2 beads (BD Biosciences) were then added to remove thymocytes from the cell suspension using a magnet before sorting TECs.

Quantitative PCR

Total RNA was extracted with TRIzol reagent (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA). One microgram (or less) of total RNA was subjected to reverse transcription to synthesize single-strand DNA (ssDNA). An aliquot of ssDNA was used as a template in PCR to quantify the mRNA of hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyltransferase (HPRT), interleukin-7 (IL-7) and IL-15. Quantitative PCR was performed with SYBR Premix Ex Taq (Takara, Shiga, Japan) and a Bio-Rad real-time PCR system, CFX96/384 (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). The primer sequences were as follow: IL-7 (forward): 5′-TGCTGCCTGTCACATCATC-3′, IL-7 (reverse): 5′-CGGGCAATTACTATCAGTTCC-3′, IL-15 (forward): 5′-TCCCTAAAACAGAGGCCAAC-3′, IL-15 (reverse): 5′-GCAACTGGGATGAAAGTCAC-3′, IL-15Rα (forward): 5′-CCCCACAGTTCCAAAATGAC-3′, IL-15Rα (reverse): 5′-TGTTTCCATGGTTTCCACCT-3′, HPRT (forward): 5′-TGGATACAGGCCAGACTTTG-3′, HPRT (reverse): 5′-AACTTGCGCTCATCTTAGGC-3′.

ELISA

CD4+ (1 × 105/well) or DN (0·6 × 105/well) cells expressing both NK1.1 and TCR-αβ in the thymi from aly/aly or aly/+ mice were sorted by FACSAria and were stimulated with plate-bound anti-CD3 antibody for 20 hr. The concentration of IFN-γ, IL-4 or IL-17 in the culture supernatants was measured by sandwich ELISA, using ‘high-binding’ enzyme immunoassay/radioimmunoassay plates (Costar, Corning, NY), purified or biotinylated antibodies (BioLegend), and horseradish peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL). As the substrate for peroxidase, a 3,3′,5,5′-tetramethylbenzidine liquid substrate system (Sigma, St Louis, MO) was used, and by adding the same amount of 0.5 M H2SO4, the reaction was stopped to measure the absorbance at 450 nm.

Cell-mediated lysis assay

Cytotoxic activities were measured by re-directed assay using FcR+ murine B lymphoma, A20.2J, as described previously.26 Briefly, A20.2J cells were labelled with 100 μCi of Na251CrO4 for 1 hr at 37° in a 10% CO2 incubator. Washed target cells (2500 cells/well) were incubated with FACS-sorted NKT cells in the presence of 1 μg/ml of anti-CD3 antibody in a round-bottom 96-well plate for 16 hr in a CO2 incubator at 37°. The radioactivities in the supernatants were measured with a γ-counter. Specific lysis was calculated as follows: % specific release = 100 × (experimental release − spontaneous release)/(maximal release − spontaneous release). Spontaneous release or maximum release was determined from wells with target cells alone or wells in which target cells were lysed with 0·5% Nonidet P-40, respectively. Assays were conducted in triplicate.

Statistical analysis

Results are expressed as the mean ± SD for each group of mice. Statistics were determined using unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test.

Results

Differential susceptibility among NKT-αβ cell subsets against NIK mutation in their differentiation

To investigate the possible difference among the subsets of NKT-αβ cells in the impact of NIK deficiency on their generation, the NKT cells in various tissues of aly/aly mice were analysed, separating them into three populations according to their co-receptor expression. The NKT-αβ cells were also analysed by dividing them into iNKT and non-iNKT cells, using a CD1d–immunoglobulin fusion protein loaded with α-GalCer to specifically detect type I iNKT cells. Figure1 shows the percentage of total NK1.1+ cells in TCR-αβ+ cells from different tissues of aly/+ or aly/aly mice, and it was confirmed that the proportion of NKT-αβ cells is severely decreased in aly/aly mice, although the level of reduction varied from tissue to tissue. The reduction of NKT-αβ cells was relatively prominent in the thymus and liver where the proportion of iNKT cells is higher.27

Figure 1.

The proportion of NK1.1+ T-cell receptor-αβ (TCR-αβ) T cells in various tissues in aly/aly or aly/+ mice. The leucocytes were collected from the indicated tissues of aly/aly or aly/+ mice (n = 6) and the proportions of NK1.1+ αβ T cells in them were examined by flow cytometry. The percentages of NK1.1+ αβ T cells in total TCR-αβ+ cells are depicted, and the bar in each graph indicates the average.

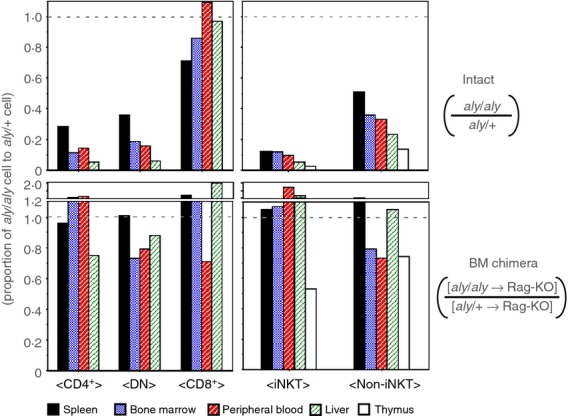

The analyses of the subpopulation revealed that the sensitivity of NKT-αβ cells to aly mutation significantly differed among the subsets (Figs2 and 3). Namely, although percentages of both iNKT and non-iNKT cells were decreased in aly/aly mice, non-iNKT cells were more resistant than iNKT cells to the absence of functional NIK. Particularly, CD8+ subsets were much less affected by NIK mutation than the other two subsets in various tissues. The same tendency was observed when analysed by cell numbers (see Supplementary material, Fig. S1). These results imply that the NIK dependence is different among the subsets of NKT-αβ cells during their generation, and therefore the developmental requirements may vary within NKT subpopulations.

Figure 2.

Analyses of NK1.1+ αβ T cells in bone marrow from aly/aly or aly/+ mice. Bone marrow cells from aly/aly or aly/+ mice were analysed for CD4 or CD8 expression and for binding of α-GalCer/CD1d dimer. (a) The representative FACS profiles are shown. In the left panels, the expression of T-cell receptor-αβ (TCR-αβ) and NK1.1 on total leucocytes is shown where the numbers indicate the percentage of NK1.1+ αβ T cells. The NK1.1+ αβ T cells were gated to analyse their co-receptor expression (the middle panels). In the right panels, total TCR-αβ T cells were analysed for NK1.1 expression and α-GalCer/CD1d binding. (b, c) The percentages of NK1.1+ αβ T cells of the indicated phenotypes from bone marrow of aly/aly or aly/+ mice are shown.

Figure 3.

The differential requirement for nuclear factor-κB-inducing kinase (NIK) among the subsets of NK1.1+ αβ T cells in their optimal generation. The NK1.1+ αβ T cells from thymus, spleen, peripheral blood and liver of aly/aly or aly/+ mice were analysed by flow cytometry, and the results are shown in the same manner as in Fig.2.

Recovery of aly/aly NKT-αβ cell generation in BM chimera with wild-type hosts received with aly/aly BM

Previous studies with BM chimeric mice demonstrated that iNKT cell generation is restored when wild-type mice are used as hosts, but not when aly/aly are used as recipients.12–14 We then examined whether differentiation of non-iNKT cells could also be recovered from aly/aly BM cells when transferred in the wild-type recipients. As shown in Fig.4, generation of iNKT and non-iNKT cells was similarly restored in BM chimera with the wild-type hosts. Whereas the effect of NIK in donor cells was not assessed in this setting, there could be some cell-autonomous role of NIK in NKT-αβ cell development, as percentages of both subsets of iNKT cells in the thymus of the wild-type hosts tended to be lower when the aly/aly donor was used than when aly/+ cells were transferred. However, the results in this experiment showed the significance of the T-cell-extrinsic role of NIK in the generation not only of iNKT but also of non-iNKT cells at normal numbers.

Figure 4.

Recovery of nuclear factor-κB-inducing kinase (NIK) -deficient NK1.1+, αβ T-cell generation in bone marrow chimera of wild-type hosts injected with aly/aly donor cells (upper panels). The average number of aly/aly natural killer T (NKT) cells obtained from the indicated organs were divided by the aly/+ NKT cell number, and the proportion of aly/aly against aly/+ are shown (lower panels). The bone marrow chimeric mice were prepared by transfusing aly/aly or aly/+ bone marrow cells into irradiated RAG2-KO hosts, to evaluate the impact of NIK-impairment in non-haematopoietic cells on NK1.1+ αβ T-cell development. The proportion of aly/aly NK1.1+ αβ T cells against aly/+ cells in chimeric mice are shown. The average numbers from four to six mice for each group were used to calculate the proportion.

NIK expression in non-haematopoietic cells is also important for the generation of NK1.1+ γδ T cells or NK1.1− iNKT cells

It is known that NK1.1+ CD3+ cells contain cells expressing TCR-γδ, although its differentiation mechanisms are not well understood.28–30 The generation of this NKT subset was investigated in intact aly/aly mice and in BM chimera that were, as in the experiments in Fig.4, prepared using aly/aly BM cells as donors and wild-type mice as recipients. Reminiscent of NKT-αβ cells, the proportion (Fig.5a) and number (data not shown) of NKT-γδ cells were substantially decreased in the thymus or spleen of aly/aly mice. Although NK1.1+ γδ T cells were shown to be predominated by Vγ1+/Vδ6+ cells,28–30 the percentages of Vγ1+ or Vγ2+ cells in γδ T cells were not changed in aly/aly mice (data not shown). In a similar manner to NKT-αβ cells, the defect in the generation of NKT-γδ cells was reversed in the BM chimera with wild-type hosts, implying that optimal differentiation of NKT-γδ cells also relies upon NIK in non-haematopoietic cells, such as thymic stromal cells.

Figure 5.

The proper generation of NK1.1+ γδ T cells or NK1.1− invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells also requires nuclear factor-κB-inducing kinase (NIK) expression in non-haematopoietic cells. The thymocytes and splenocytes from aly/aly or aly/+ mice, or [aly/aly → RAG2-KO] or [aly/+ → RAG2-KO] chimera mice were analysed for the expression of NK1.1 and T-cell receptor-γδ (TCR-γδ), and for α-GalCer/CD1d-binding. (a) Representative FACS profiles of NK1.1 and TCR-γδ expression on the splenic T cells from aly/aly or aly/+ mice are demonstrated. The numbers in the panels indicate the percentage of NK1.1+ γδ T cells in CD3+ cells (upper panels). The percentage of NK1.1+ γδ T cells in CD3hi+ thymocytes (left) or of those in CD3+ splenocytes (right) from aly/aly or aly/+ mice, or from bone marrow (BM) chimera are shown (lower panels). Six mice were analysed for each group. (b) A representative set of FACS analyses of the splenic T cells from aly/aly or aly/+ mice for the expression of NK1.1 and binding of α-GalCer/CD1d are demonstrated in upper panels. In the lower panels, the average percentage of NK1.1− iNKT cells from six mice of aly/aly or aly/+ mice, or BM chimera are presented.

It has recently been demonstrated that iNKT cells consist of some functionally different subsets. Among them, IL-17-producing iNKT cells in the periphery were identified as NK1.1-negative iNKT cells.5 To investigate the effect of NIK deficiency on the development of this subset, the proportion of iNKT cells without NK1.1 expression in aly/aly mice was compared with that in aly/+ mice. As shown in Fig.5(b), the percentage of this subset was substantially reduced in aly/aly mice compared with that in aly/+ mice, suggesting that generation of NK1.1− iNKT cells may be also affected by NIK mutation. It was also indicated by the analyses of BM chimera that, like other NKT cell subsets, NIK expression in host cells but not haematopoietic cells was sufficient for the differentiation of NK1.1− iNKT cells. Hence, although it is suggested that developmental programmes differ among NKT cell subsets, NIK expression (probably in thymic stromal cells) appears to be a common critical requirement for optimal generation of most NKT cell subsets.

IL-7 or IL-15 expression in cortical thymic epithelial cells was not impaired in aly/aly mice

As the results of BM chimera experiments described above suggested that the defect in NKT cell differentiation was attributable to the host cells rather than to the donor BM cells, and as NKT-αβ cells crucially demand IL-7 and IL-15 during their differentiation and/or in peripheral persistence,31,32 the expression of IL-7 or IL-15 mRNA in TECs of aly/aly mice were compared with those of aly/+ mice. The thymi from aly/aly or aly/+ mice were treated with Liberase to isolate TECs and the cells underwent flow cytometric cell sorting after removing thymocytes from the cell samples to enrich TECs. The TECs were detected as CD45− CD326 (EpCAM-1)+ cells, which can be further divided into two populations; UEA-1-binding medullary TECs (mTECs) and Ly51+ cortical TECs (cTECs). As shown in Fig.6(a), the percentage of mTECs was profoundly decreased in the aly/aly thymus, consistent with earlier reports showing that mTEC formation is impaired in the absence of molecules essentially involved in the non-canonical pathway of NF-κB activation.33

Figure 6.

Normal expression of interleukin-7 (IL-7) or IL-15 mRNA in cortical thymic epithelial cells (TECs) from aly/aly mouse. The thymi from aly/aly or aly/+ mice were treated with Liberase and the cells were stained with antibodies to CD45, CD326 (EpCAM-1), or Ly51, and with Ulex Europaeus Agglutinin 1 (UEA-1), to sort cortical (cTECs) or medullary (mTECs). (a) The expression of CD45 and CD326 on total cells from thymus are shown in upper panels. The CD45− CD326+ TECs were further separated into Ly51+ cTECs and UEA-1-binding mTECs (lower panels). (b) Total RNA was extracted from FACS-sorted cTECs of aly/aly or aly/+ mice to quantify the mRNA of IL-7 or IL-15. (c) The mRNA of IL-7, IL-15, or IL-15Rα expressed in cTECs or mTECs from wild-type mice were compared. Relative amounts of each mRNA normalized with Hprt mRNA are displayed. Similar results were obtained from three or four independent experiments and a representative set of results is shown.

Then, cTECs of aly/aly or aly/+ mice were sorted to examine IL-7 or IL-15, or IL-15Rα (required for trans-presentation of IL-15) mRNA expression. Figure6(b) shows that the mRNA expression level of either one of them was not significantly different between the aly/aly and aly/+ mice, indicating that the functional NIK is dispensable for cTECs in producing these cytokines or a cytokine receptor. However, analyses of the wild-type TECs indicated that a major source of IL-15 may be the mTECs (Fig.6c), so it is still possible that impaired development of mTEC might lead to a shortage of IL-15 supply for optimal generation of NKT cells in aly/aly mice, as was recently suggested.34

NIK may not be an absolute requirement for NKT-αβ cells to exert their effector function

It has been suggested that NIK is involved in TCR signalling,16,19 and several studies have demonstrated that the cytokine production from conventional CD4+ T cells in NIK mutant mice was indeed affected.16–21 However, the role of NIK in the function of NKT-αβ cells has not formally been evaluated, mainly because of developmental impairment of NKT cells in NIK-deficient mice. We therefore investigated whether NIK in NKT-αβ cells critically contributes to any effector function evoked by TCR stimulation. We obtained NIK-mutated NKT-αβ cells from [aly/aly → RAG-KO] chimera to compare their cellular function with those of aly/+ NKT-αβ cells from [aly/+ → RAG-KO] chimera. The ability of cytokine production was first assessed for FACS-sorted NK1.1+ αβ T cells of CD4+ or DN subsets from the thymi by stimulating the cells with plate-bound anti-CD3 antibody. Although IL-17 was not detected, IFN-γ and IL-4 were detected from both CD4+ and DN NKT-αβ cells, and there were no significant differences in the amount of secreted cytokines between aly/aly NKT cells and aly/+ NKT cells (Fig.7a). We then examined another function of NKT cells, cytolytic activity, of NKT-αβ cells sorted from BM. As shown in Fig.7(b), the cytotoxicity was observed in aly/aly NKT cells of CD8+, CD4+ and DN subsets at levels equivalent to those in aly/+ NKT cells. Although effector cells were sorted without using an α-GalCer/CD1d dimer, more than 90% of CD8+ or DN cells from both chimeric mice were non-iNKT-αβ cells (see Fig.7). These results indicate that, contrary to conventional CD4+ T cells16–21 or γδ T cells,22 NIK expression in NKT-αβ cells may be dispensable for their functions such as cytokine production or cytotoxicity.

Figure 7.

The nuclear factor-κB-inducing kinase (NIK) in NK1.1+ αβ T cells is dispensable for their function of cytokine production or cytolysis. The NK1.1+ αβ T cells were sorted from [aly/aly → RAG2-KO] or [aly/+ → RAG2-KO] chimera mice and their functions were investigated. (a) Either 100 or 50 000 of CD4+ or double-negative (DN) NK1.1+ αβ T cells, respectively, were stimulated in vitro with anti-CD3 antibody, coated on the surface of the wells at 10 μg/ml. After 20 hr, the concentration of interferon-γ (IFN-γ) or interleukin-4 (IL-4) in the supernatants was quantified by ELISA. The proportion of invariant natural killer T (iNKT) cells in the CD4+ subset was 85·1 ± 2·7% for aly/+ donor mice, and 83·4 ± 3·3% for aly/aly donor mice. The iNKT proportion in DN cells was 61·7 ± 11·6% for aly/+ donor mice, and 60·2 ± 4·0% for aly/aly donor mice. (b) The NK1.1+ αβ T cells of indicated phenotype were sorted from bone marrow (BM) of aly/aly or aly/+ mice and used as effector cells in re-directed cell-mediated lysis assay to examine their cytolytic activity. The proportion of iNKT cells in CD8+, DN or CD4+ subsets in bone marrow were as follows: in CD8+ cells, 1·0 ± 0·6% for aly/+ donor mice, and 1·8 ± 1·5% for aly/aly donor mice; in DN cells, 8·5 ± 0·9% for aly/+ donor mice and 8·6 ± 2·9% for aly/aly donor mice; and in CD4+ cells, 62·3 ± 5·8% for aly/+ donor mice and 53·5 ± 11·0% for aly/aly donor mice.

Discussion

Because type I iNKT cells make up a major portion of NKT cells, and because iNKT cells could be specifically activated or detected by the use of prototypic antigen α-GalCer, their function or development have been well documented.1 Recently, various roles played by type II NKT cells in immune responses against pathogen or tumour, or in inflammation or autoimmunity, have been revealed. In several experimental settings, it was suggested that they mostly play protective roles,2 so clinical exploitation of these cells is expected, particularly in anti-tumour therapy.7 Nonetheless, despite the fact that NKT cells consist of several subpopulations, the analyses of NKT cells separating them into distinct subsets have not been thoroughly performed, and information on the molecular mechanism for their developmental diversification is limited.

We previously reported that the number and proportion of NKT-αβ cells are severely reduced in aly/aly mice, and that the defects may reside in TECs.12,15 In the present study, we extended this notion by exploring the potential difference in NIK dependence among the subsets of NKT cells. We also examined the requirement of NIK in the function of mature NKT-αβ cells by investigating NIK-defected NKT-αβ cells. From these analyses, several novel insights on the roles of NIK in NKT developments and functions have been provided. First, the dependence of NKT-αβ cell differentiation on NIK may vary in the subsets, although they all require NIK expressed in non-haematopoietic cells such as thymic stromal cells, for proper differentiation. Second, the optimal generation of NKT-γδ cells also demands T-cell-extrinsic NIK. Third, NIK play a non-redundant role in NKT-αβ cell development other than in the secretion of IL-7 or IL-15 from cTECs. And lastly, in contrast to conventional CD4+ T cells or γδ T cells, NIK in NKT-αβ cells appeared dispensable for either IFN-γ or IL-4 production, or for cytolysis by them.

As mentioned above, the current results revealed that the development of type I NKT cells requires NIK more critically than that of non-iNKT cells. In particular, CD8+ NKT-αβ cells seemed rather refractory to systemic lack of NIK for their generation. In spite of their substantial existence in periphery, the function or developmental pathway of CD8+ NKT-αβ cells have not been revealed in detail. It was herein demonstrated that these cells are cytolytic, but understanding their cytokine production capability needs further investigation. Given the relatively low dependency on NIK of CD8+ NKT-αβ cells, their developmental pathway may be different from that of other subsets of NKT cells, indicating the possibility that the requirement for differentiation could vary among the subsets of NKT-αβ cells. In fact, CD8+ NKT-αβ cells develop independently of CD1d, as demonstrated by Eberl et al.27 It is tempting to speculate that NIK could be involved in diversification of NKT-αβ cells. Although MR1-restricted mucosal-associated invariant T (MAIT) cells were shown to contain CD8+ cells,35 this population may not be MAIT cells, because the proportion of NK1.1+ CD8+ T cells did not decrease in MR1−/− mice (data not shown). Also, the frequency of type II NKT cells that recognize sulfatide has remained unclear, because we were not able to detect a fraction of type II NKT cells as a significant population when we stained wild-type cells with sulfatide/CD1d tetramer (data not shown).

Whereas the majority of NKT cells express TCR-αβ, a small portion of NKT cells express TCR-γδ. Similarly to NKT-αβ cells, most NKT-γδ cells express some activation marker constitutively, and can promptly secrete IL-4 and IFN-γ upon TCR stimulation.29,36 However, the developmental program of NKT-γδ cells may be different from that of NKT-αβ cells. Unlike NKT-αβ cells, NKT-γδ cells are thought to develop mostly from CD4/CD8 DN progenitors rather than CD4/CD8 double-positive cells,36 independently of β2-microglobulin-associated class I MHC molecules.37 Furthermore, it was shown that NKT-γδ cells can develop independently of Src kinase Fyn, without which, differentiation of NKT-αβ cells is severely perturbed.38 Regardless of these distinctions in their developmental pathways, our present study demonstrated that the NIK expression in non-haematopoietic cells is a common requirement for the adequate generation of NKT-αβ and NKT-γδ cells. Although it has been shown that NKT-γδ cells segregate in a tissue-specific manner, and that the characteristics of NKT-γδ cells differ between those in the spleen and those in the thymus in terms of their TCR repertoire and activation/memory marker expression,30 NIK was essential for the proper generation of both thymic and splenic NKT-γδ cells. To our knowledge, NIK is the only extrinsic factor necessary for optimal development of NKT-γδ cells. However, further studies are required to uncover the role of NIK in supporting the development of the NKT cell subsets, including NKT-γδ cells.

Although NIK is documented primarily in the non-canonical pathway of NF-κB activation triggered by the signalling from Toll-like receptor or tumour necrosis factor receptor family molecules, it was also suggested to be involved in the signalling from antigen receptors.16–21 However, no significant differences in IL-4 nor IFN-γ production were found upon CD3-stimulation from CD4+ or DN NKT-αβ cells between aly/aly and aly/+ mice. These results suggested that NIK in NKT-αβ cells are dispensable both in TCR-mediated positive selection of NKT-αβ cells and in TCR-mediated effector functions of mature cells. This is in contrast to conventional αβ16–21 and γδ T cells22 where NIK in TCR-signalling is pivotal in proper cytokine secretion. This observation indicated a possibility that the molecular programmes for TCR signalling leading to IFN-γ or IL-4 production could be different between conventional T cells and NKT-αβ cells.

The results of BM chimera clearly indicate the significance of NIK in host cells for NKT-αβ cells21 (and this study) or γδ T cells22 for their efficient maturation. In our unpublished study using TCR-transgenic mice, it was suggested that the positive selection of conventional T cells bearing particular TCR was attenuated in an aly/aly background, and here again, absence of NIK in non-haematopoietic cells was found to be responsible for it (K. Eshima and K. Iwabuchi, manuscript in preparation). Hence, the thymic environment of aly/aly mice seems to affect the development of essentially all subsets of T cells. In development and maintenance of γδ and NKT-αβ cells, IL-7 and IL-15 were demonstrated to play important roles.31,32,39 However, the mRNA expression of these cytokine in cTECs was indistinguishable between aly/aly and aly/+ mice. Whereas cTECs were a major source of IL-7 in the thymus, IL-15 seemed to be produced mainly by mTECs rather than cTECs. Therefore, it is possible that the IL-15 supply in the medullary region of the thymus may be critical during the development of NKT cells. In fact, it is known that NKT cells development is defective in several mouse lines deficient for mTECs.40–46 Nevertheless, the precise roles of mTECs in supporting NKT cell development remain to be investigated, which is one of our on-going subjects.

Acknowledgments

HN, MS and KE performed experiments. KE and KI designed experiments and wrote the paper. KI organized the study. The authors are grateful to Dr Michiyuki Kasai (Kochi Medical School) and Dr Yan Xing (University of Minnesota) for valuable advice on the preparation of thymic epithelial cells. This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (KAKENHI) (26430120 to KE).

Glossary

- BM

bone marrow

- iNKT

invariant NKT

- NIK

NF-κB-inducing kinase

- NKT cell

natural killer T cell

- TCR

T-cell receptor

- TECs

thymic epithelial cells

- α-GalCer

α-galactosylceramide

Disclosures

The authors have no financial and commercial conflicts of interest.

Supporting Information

Figure S1. Comparison of the absolute number of NK1.1+, αβ T cells in aly/aly or aly/+ mice.

References

- Bendelac A, Savage PB, Teyton L. The biology of NKT cells. Annu Rev Immunol. 2007;25:297–336. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V, Delovitch TL. Different subsets of natural killer T cells may vary in their roles in health and disease. Immunology. 2014;142:321–36. doi: 10.1111/imm.12247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watarai H, Sekine-Kondo E, Shigeura T, et al. Development and function of invariant natural killer T cells producing Th2- and Th17-cytokines. PLoS Biol. 2012;10:e1001255. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YJ, Holzapfel KL, Zhu J, Jameson SC, Hogquist KA. Steady-state production of IL-4 modulates immunity in mouse strains and is determined by lineage diversity of iNKT cells. Nat Immunol. 2013;14:1146–54. doi: 10.1038/ni.2731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel ML, Mendes-da-Cruz D, Keller AC, Lochner M, Schneider E, Dy M, Eberl G, Leite-de-Moraes MC. Critical role of ROR-γt in a new thymic pathway leading to IL-17-producing invariant NKT cell differentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:19845–50. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806472105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godfrey DI, Stankovic S, Baxter AG. Raising the NKT cell family. Nat Immunol. 2010;11:197–206. doi: 10.1038/ni.1841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terabe M, Berzofsky JA. The immunoregulatory role of type I and type II NKT cells in cancer and other diseases. Cancer Immunol Immunother. 2014;63:199–213. doi: 10.1007/s00262-013-1509-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malinin NL, Boldin MP, Kovalenko AV, Wallach D. MAP3K-related kinase involved in NF-κB ind uction by TNF, CD95 and IL-1. Nature. 1997;385:540–4. doi: 10.1038/385540a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun S-C. The noncanonical NF-κB pathway. Immunol Rev. 2012;246:125–40. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01088.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyawaki S, Nakamura Y, Suzuka H, Koba M, Yasumizu R, Ikehara S, Shibata Y. A new mutation, aly, that induces a generalized lack of lymph nodes accompanied by immunodeficiency in mice. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24:429–34. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinkura R, Kitada K, Matsuda F, et al. Alymphoplasia is caused by a point mutation in the mouse gene encoding NF-κB-inducing kinase. Nat Genet. 1999;22:74–7. doi: 10.1038/8780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa K, Iwabuchi K, Ogasawara K, et al. Generation of NK1.1+ T cell antigen receptor αβ+ thymocytes associated with intact thymic structure. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:2472–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.6.2472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivakumar V, Hammond KJ, Howells N, Pfeffer K, Weih F. Differential requirement for Rel/nuclear factor κB family members in natural killer T cell development. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1613–21. doi: 10.1084/jem.20022234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elewaut D, Shaikh RB, Hammond KJ, et al. NIK-dependent RelB activation defines a unique signaling pathway for the development of Vα 14 iNKT cells. J Exp Med. 2003;197:1623–33. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konishi J, Iwabuchi K, Iwabuchi C, et al. Thymic epithelial cells responsible for impaired generation of NK-T thymocytes in Alymphoplasia mutant mice. Cell Immunol. 2000;206:26–35. doi: 10.1006/cimm.2000.1723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishimaru N, Kishimoto H, Hayashi Y, Sprent J. Regulation of naive T cell function by the NF-κB2 pathway. Nat Immunol. 2006;7:763–72. doi: 10.1038/ni1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin W, Zhou XF, Yu J, Cheng X, Sun SC. Regulation of Th17 cell differentiation and EAE induction by MAP3K NIK. Blood. 2009;113:6603–10. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-12-192914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray SE, Polesso F, Rowe AM, Basak S, Koguchi Y, Toren KG, Hoffmann A, Parker DC. NF-κB–inducing kinase plays an essential T cell-intrinsic role in graft-versus-host disease and lethal autoimmunity in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:4775–86. doi: 10.1172/JCI44943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsumoto M, Yamada T, Yoshinaga SK, Boone T, Horan T, Fujita S, Li Y, Mitani T. Essential role of NF-κB-inducing kinase in T cell activation through the TCR/CD3 pathway. J Immunol. 2002;169:1151–8. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.3.1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamada T, Mitani T, Yorita K, Uchida D, Matsushima A, Iwamasa K, Fujita S, Matsumoto M. Abnormal immune function of hemopoietic cells from alymphoplasia (aly) mice, a natural strain with mutant NF-κB-inducing kinase. J Immunol. 2000;165:804–12. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann J, Mair F, Greter M, Schmidt-Supprian M, Becher B. NIK signaling in dendritic cells but not in T cells is required for the development of effector T cells and cell-mediated immune responses. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1917–29. doi: 10.1084/jem.20110128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshima K, Okabe M, Kajiura S, Noma H, Shinohara H, Iwabuchi K. Significant involvement of nuclear factor-κB-inducing kinase in proper differentiation of αβ and γδ T cells. Immunology. 2014;141:222–32. doi: 10.1111/imm.12186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treiner E, Duban L, Bahram S, et al. Selection of evolutionarily conserved mucosal-associated invariant T cells by MR1. Nature. 2003;422:164–9. doi: 10.1038/nature01433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinkai Y, Rathbun G, Lam KP, et al. RAG-2-deficient mice lack mature lymphocytes owing to inability to initiate V(D)J rearrangement. Cell. 1992;68:855–67. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90029-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing Y, Hogquist KA. Isolation, identification, and purification of murine thymic epithelial cells. J Vis Exp. 2014;90:e51780. doi: 10.3791/51780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eshima K, Chiba S, Suzuki H, Kokubo K, Kobayashi H, Iizuka M, Iwabuchi K, Shinohara N. Ectopic expression of a T-box transcription factor, eomesodermin, renders CD4+ Th cells cytotoxic by activating both perforin- and FasL-pathways. Immunol Lett. 2012;144:7–15. doi: 10.1016/j.imlet.2012.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberl G, Lees R, Smiley ST, Taniguchi M, Grusby MJ, MacDonald HR. Tissue-specific segregation of CD1d-dependent and CD1d-independent NK T cells. J Immunol. 1999;162:6410–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira P, Berthault C, Burlen-Defranoux O, Boucontet L. Critical role of TCR specificity in the development of Vγ1Vδ6.3+ innate NKTγδ cells. J Immunol. 2013;191:1716–23. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin CC, Cho OH, Sylvia KE, Narayan K, Prince AL, Evans JW, Kang J, Berg LJ. The Tec kinase ITK regulates thymic expansion, emigration, and maturation of γδ NKT cells. J Immunol. 2013;190:2659–69. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lees RK, Ferrero I, MacDonald HR. Tissue-specific segregation of TCRgamma delta+ NKT cells according to phenotype TCR repertoire and activation status: parallels with TCR αβ+ NKT cells. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:2901–9. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(2001010)31:10<2901::aid-immu2901>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda JL, Gapin L, Sidobre S, Kieper WC, Tan JT, Ceredig R, Surh CD, Kronenberg M. Homeostasis of Vα14i NKT cells. Nat Immunol. 2002;3:966–74. doi: 10.1038/ni837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ranson T, Vosshenrich CA, Corcuff E, Richard O, Laloux V, Lehuen A, Di Santo JP. IL-15 availability conditions homeostasis of peripheral natural killer T cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:2663–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0535482100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson G, Takahama Y. Thymic epithelial cells: working class heroes for T cell development and repertoire selection. Trends Immunol. 2012;33:256–63. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2012.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White AJ, Jenkinson WE, Cowan JE, Parnell SM, Bacon A, Jones ND, Jenkinson EJ, Anderson G. An essential role for medullary thymic epithelial cells during the intrathymic development of invariant NKT cells. J Immunol. 2014;192:2659–66. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reantragoon R, Corbett AJ, Sakala IG, et al. Antigen-loaded MR1 tetramers define T cell receptor heterogeneity in mucosal-associated invariant T cells. J Exp Med. 2013;210:2305–20. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grigoriadou K, Boucontet L, Pereira P. Most IL-4–producing γδ thymocytes of adult mice originate from fetal precursors. J Immunol. 2003;171:2413–20. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.5.2413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vicari AP, Mocci S, Openshaw P, O’Garra A, Zlotnik A. Mouse γδ TCR+ NK1.1+ thymocytes specifically produce interleukin-4, are major histocompatibility complex class I independent, and are developmentally related to αβ TCR+ NK1.1+ thymocytes. Eur J Immunol. 1996;26:1424–9. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830260704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alonzo ES, Gottschalk RA, Das J, et al. Development of promyelocytic zinc finger and ThPOK-expressing innate γδ T cells is controlled by strength of TCR signaling and Id3. J Immunol. 2010;184:1268–79. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shitara S, Hara T, Liang B, et al. IL-7 produced by thymic epithelial cells plays a major role in the development of thymocytes and TCRγδ+ intraepithelial lymphocytes. J Immunol. 2013;190:6173–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burkly L, Hession C, Ogata L, et al. Expression of relB is required for the development of thymic medulla and dendritic cells. Nature. 1995;73:531–6. doi: 10.1038/373531a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weih F, Carrasco D, Durham S, Barton D, Rizzo C, Ryseck R, Lira SA, Bravo R. Multiorgan inflammation and hematopoietic abnormalities in mice with a targeted disruption of RelB, a member of the NF-κB/Rel family. Cell. 1995;80:331–40. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90416-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinoshita D, Hirota F, Kaisho T, Kasai M, Izumi K, Bando Y, Lira SA, Bravo R. Essential role of IκB kinase α in thymic organogenesis required for the establishment of self-tolerance. J Immunol. 2006;176:3995–4002. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.7.3995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lomada D, Liu B, Coghlan L, Hu Y, Richie ER. Thymus medulla formation and central tolerance are restored in IKKα–/– mice that express an IKKα transgene in keratin 5+ thymic epithelial cells. J Immunol. 2007;178:829–37. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.2.829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang B, Wang Z, Ding J, Peterson P, Gunning WT, Ding HF. NF-κB2 is required for the control of autoimmunity by regulating the development of medullary thymic epithelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:38617–24. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606705200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu M, Chin RK, Christiansen PA, Lo JC, Liu X, Ware C, Siebenlist U, Fu YX. NF-κB2 is required for the establishment of central tolerance through an Aire-dependent pathway. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2964–71. doi: 10.1172/JCI28326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama T, Maeda S, Yamane S, Ogino K, Kasai M, Kajiura F, Matsumoto M, Inoue J. Dependence of self-tolerance on TRAF6-directed development of thymic stroma. Science. 2005;308:248–51. doi: 10.1126/science.1105677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Comparison of the absolute number of NK1.1+, αβ T cells in aly/aly or aly/+ mice.