Abstract

Anthropogenic deforestation has shaped ecosystems worldwide. In subarctic ecosystems, primarily inhabited by native peoples, deforestation is generally considered to be mainly associated with the industrial period. Here we examined mechanisms underlying deforestation a thousand years ago in a high-mountain valley with settlement artifacts located in subarctic Scandinavia. Using the Heureka Forestry Decision Support System, we modeled pre-settlement conditions and effects of tree cutting on forest cover. To examine lack of regeneration and present nutrient status, we analyzed soil nitrogen. We found that tree cutting could have deforested the valley within some hundred years. Overexploitation left the soil depleted beyond the capacity of re-establishment of trees. We suggest that pre-historical deforestation has occurred also in subarctic ecosystems and that ecosystem boundaries were especially vulnerable to this process. This study improves our understanding of mechanisms behind human-induced ecosystem transformations and tree-line changes, and of the concept of wilderness in the Scandinavian mountain range.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s13280-015-0634-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Betula pubescens ssp. czerepanovii, Forest history, Indigenous, Modeling, Simulation, Vegetation change

Introduction

Historically, deforestation (temporary or permanent clearance of forests by people) has been one of the main factors shaping terrestrial environments (Kaplan et al. 2009; McWethy et al. 2010; Hughes 2011). Permanent deforestation in temperate ecosystems is primarily attributed to the advance of agriculture since the early Neolithic (Harris 1996; Kaplan et al. 2009). However, in northern boreal and subarctic ecosystems, deforestation is generally considered to be much more recent and primarily associated with industrialization (Williams 2003, but see also Simpson et al. 2003).

Deforestation is a complex process involving interactions among diverse ecological factors such as tree species composition, natural regeneration capacity, and productivity, together with many socio-economic factors such as population sizes, economic activities, and people’s beliefs (Williams 2003; Trbojevic et al. 2012). Thus, a multidisciplinary approach is required for rigorous reconstruction and elucidation of historical deforestation processes. Notably, integrative application of archeological and ecological approaches has great potential for identifying drivers and effects of early land-use patterns (Briggs et al. 2006). Simulations of wood use and deforestation using models incorporating both ecological and socio-economic factors can be particularly effective in this context for reconstructing large-scale vegetation dynamics and previous human use and impact on forest ecosystems (Bedward et al. 2007; Lev-Yadun et al. 2010).

The sub-alpine zone of northern Europe is dominated by mountain birch [Betula pubescens ssp. czerepanovii (N.I. Orlova) Hämet-Ahti] forests, which forms an ecotone between continuous coniferous forests and treeless alpine heaths (Carlsson et al. 1999). The altitude of the tree-line—defined here as the elevation at which continuous forest gives way to alpine heaths with scattered trees (Kullman 2001)—has changed over time and is now located 700–800 m above sea level (a.s.l.) at latitudes close to the Arctic circle (Wielgolaski et al. 2005). The productivity in the mountain birch forests is generally low in terms of wood biomass, and the forests are periodically damaged by insect defoliation (Wielgolaski et al. 2005). Generally, the mountain birch forest is considered to be one of the few ecosystems in northern Europe to be virtually devoid of human effects on forest growth and structure, and tree-line dynamics are primarily considered to be driven by climate and natural disturbance (Wielgolaski et al. 2005; Moen 2008). Thus, it is generally thought that there has been little historical deforestation in this region, largely because of the low historic population densities and late arrival of agriculture.

However, recent palynological research at three localities in the Scandinavian mountain range indicates that humans have strongly influenced vegetation composition through activities that decreased forest cover during pre-historic times (Karlsson et al. 2007, 2009; Staland et al. 2011). In the present study, we examined mechanisms underlying deforestation at one of these sites, the Adamvalta Valley (66°N), located above the present local tree-line but below the regional tree-line (Fig. 1). We addressed three main questions: Firstly, was the deforestation in this valley caused by people, particularly their use of mountain birch? Secondly, what levels of land-use intensity are required for such deforestation? Thirdly, why has there been no regrowth of trees in this valley? To address the first two questions, we applied simulations using the Heureka Forestry Decision Support System (DSS) (Wikström et al. 2011), based on the physiogeography of the Adamvalta Valley, estimated human population during the occupancy period, empirical data on the sub-alpine birch forest structure, and estimated rates of fuel-wood collection and consumption. The simulations enabled us to model pre-settlement conditions and effects of tree cutting on forest cover during the settlement period, c. AD 800–1200 (unless specified otherwise, all ages presented below are in calibrated years). Information on population densities, habitation patterns, and tree-line altitudes during the settlement period is ambiguous; therefore, we simulated scenarios based on two estimates of habitation density, four habitation periods, and two estimates of tree-line altitude. To address the third question, we estimated total ecosystem nitrogen (N), by summing the N content of primary N pools and mineralizable N in humus and mineral soil samples in the Adamvalta Valley and a forested reference area.

Fig. 1.

View of the central part of the Adamvalta Valley. Photo by Greger Hörnberg

Study setting and overview of previous research

Study area

Today the Adamvalta Valley is a treeless valley located on the eastern side of the Scandinavian mountain range near the border between Sweden and Norway (67°01′N, 16°37′E) (Fig. 2). The floor of the valley is dominated by glaciofluvial sediment terraces and the slopes by glacial till and, in some parts, boulders. The altitude varies from c. 600 m a.s.l. at the valley bottom to over 1200 m at the tops of mountains surrounding the valley. The vegetation is low-alpine heath, dominated by Empetrum hermaphroditum Hagerup, Vaccinium spp., Arctostaphylos alpinus Adans. and Betula nana L. (Carlsson et al. 1999). The present tree-line in nearby mountain valleys is situated at c. 750 m a.s.l.

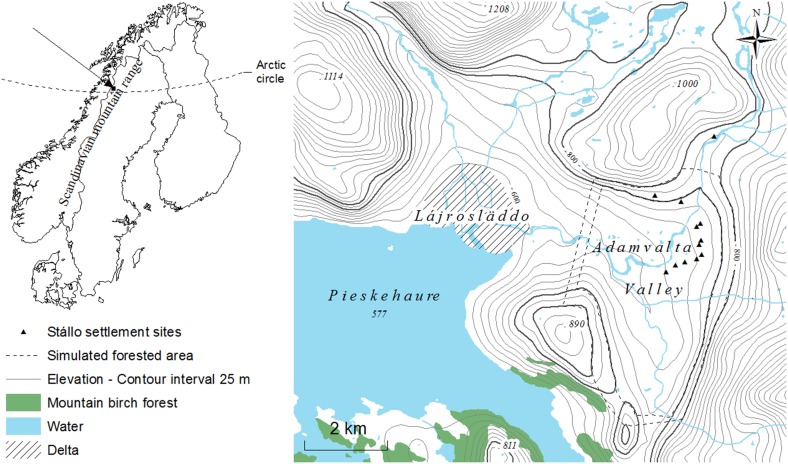

Fig. 2.

Location and topographic map showing the position of the Adamvalta Valley (including the Stállo settlements and with the elevation contours 750 and 800 m a.s.l. highlighted)

Archeological investigations and interpretations of local societal structure

Stállo foundations are specific forms of archeological monuments that represent remnants of settlements are scattered throughout the Scandinavian mountain range in both alpine heaths and sub-alpine birch forest close to the forest limit. They consist of an oval area, a sunken floor with a hearth in the center, surrounded by a low soil embankment. In the Adamvalta Valley, 31 stállo foundations (at 12 settlement sites, each with 1–5 foundations—Fig. 2) have been found, and extensive accelerator mass spectrometric (AMS) 14C-analysis of burnt wood excavated from the hearths indicates a continuous settlement period from AD 800–1050 (Liedgren et al. 2007; Bergman et al. 2008). Analysis of the burnt wood has shown that it consists almost exclusively of mountain birch (Hellberg 2004), providing conclusive evidence that such wood was available locally during the settlement period.

Paleoecological investigations

Studies by Hellberg (2004) and Karlsson et al. (2007) suggest that the Adamvalta Valley used to be forested with mountain birch and that a deforestation process coincided with the settlement period. Their results provide evidence of a sharp shift in vegetation around AD 1050 from mountain birch woodland to alpine heath (a dramatic decrease in abundance of mountain birch pollen accompanied by a strong increase in abundance of pollen from dwarf shrubs such as Salix spp. and B. nana). It has further been suggested that subsequent mountain birch regeneration was impaired by herbivore grazing and trampling, increasing climatic harshness during the Little Ice Age (LIA, c. AD 1300–1800), and nutrient degradation of the area (DeLuca et al. 2002; Karlsson et al. 2007; Staland et al. 2011). The major drivers of this deforestation cannot be firmly determined by pollen and charcoal analyses.

Experimental studies

A major problem when interpreting pre-historical and historical forest use is the lack of robust quantitative data on fuel-wood consumption (cf. Williams 2003; Trbojevic et al. 2012). In order to overcome this obstacle, Liedgren and Östlund (2011) experimentally evaluated the volume of wood consumed by occupants of a stállo-hut under realistic conditions, using unseasoned mountain birch wood. Their results indicate that c. 26.2 m3 of birch wood was consumed per stállo-hut annually—estimates based on 6 months of high-intensity fires in a hut (winter conditions), 3 months of medium intensity fires (autumn and spring, 50% of winter wood consumption), and 3 months of low intensity fires (summer, 25% of winter wood consumption).

Materials and methods

Simulation model

To model the pre-deforestation state of the forest landscape, tree volumes, growth rates, and cutting patterns in the Adamvalta Valley, we used the Heureka Forestry DSS (PlanWise version 1.9.8). Heureka can simulate forest landscapes and succession in them using selected single-tree growth, in-growth, and mortality models to describe the tree layer’s development, as described by Wikström et al. (2011). The system is designed to handle tree-level data obtained from inventories, and/or other appropriate sources, such as remote sensing images and stand-level empirical measurements (Wikström et al. 2011).

Input data

The pre-deforestation state was reconstructed using empirical data on forest structure recorded in the field, and the basic parameters latitude, altitude, and both soil and water conditions. Data on tree species composition, tree density, height, age, and diameter were acquired in 2001 from surveys of 10 sample plots (100 m2) in a reference area, the Adjevaratj Valley located 11 km from the center of the Adamvalta Valley at 650–700 m a.s.l. The Adjevaratj Valley is currently forested with mountain birch, and there are no registered archeological monuments in it. In addition, we collected data on the stem form of individual trees in the plots. In 2009, the sample plots were re-inventoried to record basal area growth of individual trees, tree mortality, and in-growth of trees. The empirical data derived from the sample plots were used to adapt the Heureka model to local forest stand and growth conditions.

Scenario design

We simulated forest changes (tree cutting and volume of mountain birch trees) over 300 years in 12 scenarios based on four seasonal habitation patterns and two habitation densities (Table 1). Numbers of occupied stállo-huts and seasonal habitation patterns were also varied (as described below), and the estimated annual volume of cut wood was varied accordingly, from 74 m3 for the summer habitation of 15 stállo-huts to 818 m3 for the year-round habitation of 31 stállo-huts. The scenarios were simulated for two approximations of forested area in the valley, 720 and 921 ha, based on tree-line altitudes of 750 m a.s.l. (the current upper tree-line in the Adjevaratj reference area and surrounding valleys) and 800 m a.s.l., respectively. Scenarios for the higher tree-line altitude were simulated because the examined deforestation process coincided with a period of warmer summer temperatures in northern Scandinavia (see Osborn and Briffa 2006). Both estimates of forested area were adjusted to compensate for wetlands and non-forested land. The delimitation of the valley (i.e., simulated forested area) was based on altitude on all sides except the western side, where it ends in a large delta (Lájrosläddo) on the north side of Lake Pieskejaure (Fig. 2). Here the periphery is far from the settlement sites, and settlers would have needed to have transported wood harvested there upwards. Accordingly, on this side of the Adamvalta Valley, we set the limit at c. 1 km from the settlement sites (cf. Shackleton and Prins 1992). For detailed information on scenario design and evaluation, see Electronic Supplementary Material.

Table 1.

Description of 12 scenarios used to simulate tree cutting and changes in tree volume in the Adamvalta valley

| Scenario | Annual total wood consumption (m3)a | Habitation density (no. of occupied stállo huts) | Habitation period | Tree-line elevation (m a.s.l.) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1a | 396 (1980) | 15 | Year-round | 750 |

| 1b | 291 (1455) | 15 | Winter | 750 |

| 2a | 818 (4090) | 31 | Year-round | 750 |

| 2b | 601 (3005) | 31 | Winter | 750 |

| 2c | 223 (1115) | 31 | Spring–summer–autumn | 750 |

| 2d | 74 (370) | 31 | Summer | 750 |

| 3a | 396 (1980) | 15 | Year-round | 800 |

| 3b | 291 (1455) | 15 | Winter | 800 |

| 4a | 818 (4090) | 31 | Year-round | 800 |

| 4b | 601 (3005) | 31 | Winter | 800 |

| 4c | 223 (1115) | 31 | Spring–summer–autumn | 800 |

| 4d | 74 (370) | 31 | Summer | 800 |

aCalculations based on an annual consumption of 26.2 m3 fuel wood and 4 m3 construction wood per stállo hut. Figures within parentheses relate to total consumption in 5-year intervals. Data derived from Liedgren and Östlund (2011)

Empirical determinations of N contents in soil, biomass, and vegetation

Three separate sites, each with five 1 m2 plots, were established at the Adjevaratj reference birch forest and the heathland at Adamvalta Valley to estimate N content of soil, biomass, and vegetation. Composite samples (of three sub-samples) were collected from the humus layer and surface mineral soil in each of the plots using a corer. No visible charcoal was found in any of the samples. The 15 soil and humus samples were subsequently analyzed to determine their bulk density using the undisturbed core method (measuring the dry mass of each 98 cm3 core and dividing by volume), and total N contents by dry combustion. Further, potentially mineralizable N using a 14-day anaerobic incubation was measured on humus and soil samples collected with a corer on eight separate plots at each site and a sample created by compositing three sub-samples per plot.

Above-ground understory vegetation biomass was measured by harvesting all vegetative matter from five replicate 25 cm2 plots, drying the material at 70°C for 48 h, and then weighing its dry mass. Replicate composite samples of birch leaves and stem tissue were also collected at each of the five plots along each transect. Birch and understory vegetation samples were then dried at 70°C, ground to pass through a 76 µm mesh sieve, and analyzed for total N content by dry combustion. Total N content was then converted to unit mass per hectare (tree basal area measured by calipering all trees at breast height in ten 100 m2 plots). Total ecosystem N was estimated by summing vegetation, humus, and mineral soil N pools and comparing the Adamvalta heathland to the Adjevaratj reference forest using a T test for the three sites (n = 3) with five plots per site. Comparison of potentially mineralizable N in the Adjevaratj birch forest humus and mineral soil with that in the heathland at Adamvalta was also conducted using a two tailed T test (n = 8). All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (version 19).

Results

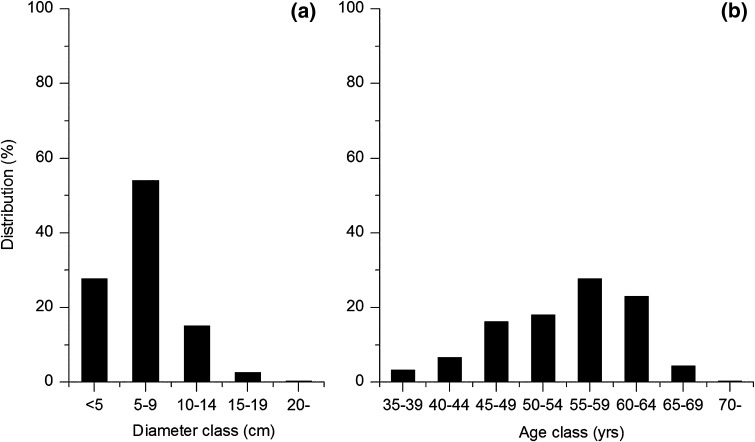

This study presupposes that the Adamvalta Valley was covered with mountain birch up to approximately 750–800 m a.s.l. at the time of the first settlement around AD 800. Pre-deforestation conditions, based on the forest structure data collected from a reference area, were reconstructed and modeled using the information presented in Table 2 and Fig. 3a and b. The average annual increase in wood biomass in the reference area is 0.4 m3 ha−1.

Table 2.

Forest characteristics used to model the pre-deforestation state in the Adamvalta Valley. Data derived from the Adjevaratj reference site

| Sample plot | Basal area (m2 ha−1) | Dbh (cm) | Stem density (ha−1) | Mean tree height (m)a | Mean age (years)b | Tree volume (m3 ha−1)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 15.8 | 8.3 | 2600 | 7.2 | 65.7 | 56.6 |

| 2 | 17.2 | 9.3 | 2400 | 7.3 | 66.0 | 63.4 |

| 3 | 4.9 | 5.0 | 2100 | 4.7 | 54.6 | 13.3 |

| 4 | 16.3 | 7.3 | 3500 | 6.6 | 62.5 | 54.5 |

| 5 | 16.7 | 7.2 | 3300 | 7.4 | 66.0 | 61.7 |

| 6 | 11.3 | 8.3 | 1800 | 7.0 | 65.7 | 40.0 |

| 7 | 10.4 | 6.5 | 2700 | 5.8 | 60.0 | 30.4 |

| 8 | 12.2 | 6.0 | 3600 | 6.2 | 60.5 | 38.7 |

| 9 | 22.4 | 9.7 | 2300 | 9.8 | 75.1 | 100.5 |

| 10 | 10.3 | 6.4 | 2700 | 5.9 | 60.5 | 31.3 |

| Mean | 13.7 | 9.9 | 2700 | 6.8 | 63.7 | 49.0 |

aTree heights were first calculated with the height function for birch by Söderberg (1992), and then calibrated by multiplying the calculated height by a factor that equals observed mean height divided by mean height based on function values. Mean tree height refers to basal area weighted mean heights

bTree ages were first calculated with tree age function for birch by Elfving (2003), and then calibrated in analogy with the tree height calibration

cTree volumes were calculated with the volume function by Brandel (1990), which uses diameter and height as explanatory variables. The measured diameter and the calibrated height for each tree were used as input

Fig. 3.

Diameter (a) and age (b) distribution of all trees recorded in the 10 sample plots in the Adjevaratj reference site

Changes in annual tree cutting

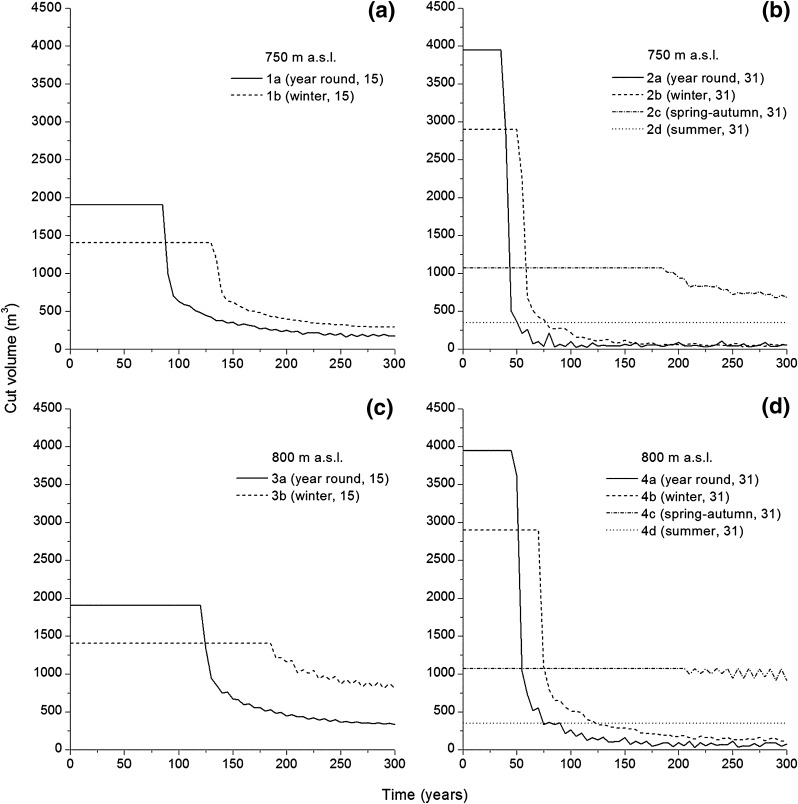

The volume of mountain birch cut annually with the lower habitation density (15 occupied stállo huts) and tree-line elevation (750 m a.s.l.) remained stable for 80 and 130 years under year-round occupation and winter occupation, respectively (scenarios 1a and b, Fig. 4a). This means that the inhabitants cut as much as they needed as long as there was enough of birch trees available and then progressively less. Modeling with a higher tree-line (800 m a.s.l.) prolonged the period of stable tree cutting by 35 years (year-round occupation) and 55 years (winter occupation) (scenarios 3a and b, Fig. 4c). With a higher habitation density (31 occupied stállo huts) and tree-line at 750 m a.s.l., the time period with stable tree cutting was 40 and 60 years under year-round and winter occupation, respectively (scenarios 2a and b, Fig. 4b). Modeling with a higher tree-line (800 m a.s.l.) slightly prolonged this time period by a further 5–10 years (scenarios 4a and b, Fig. 4d). Scenario 2c, with occupation of 31 stállo huts during spring–autumn and tree-line at 750 m a.s.l., resulted in a gradual reduction in annually cut tree volumes, starting after 185 years (Fig. 4b). Scenario 4c (31 stállo huts occupied during spring–autumn with a 800 m a.s.l. tree-line) and scenarios 2d and 4d (31 stállo huts occupied only during summer with 750 or 800 m a.s.l. tree-lines) resulted in minor (or no) changes in annual cut tree volumes (Fig. 4b, d).

Fig. 4.

Simulated cut volume (m3) at 5-year intervals for scenarios 1a–b (a) and 2a–d (b) based on an initial tree-line elevation at 750 m a.s.l., 3a–b (c), and 4a–d (d) based on an initial tree-line elevation at 800 m a.s.l

Reduction of tree volume over time

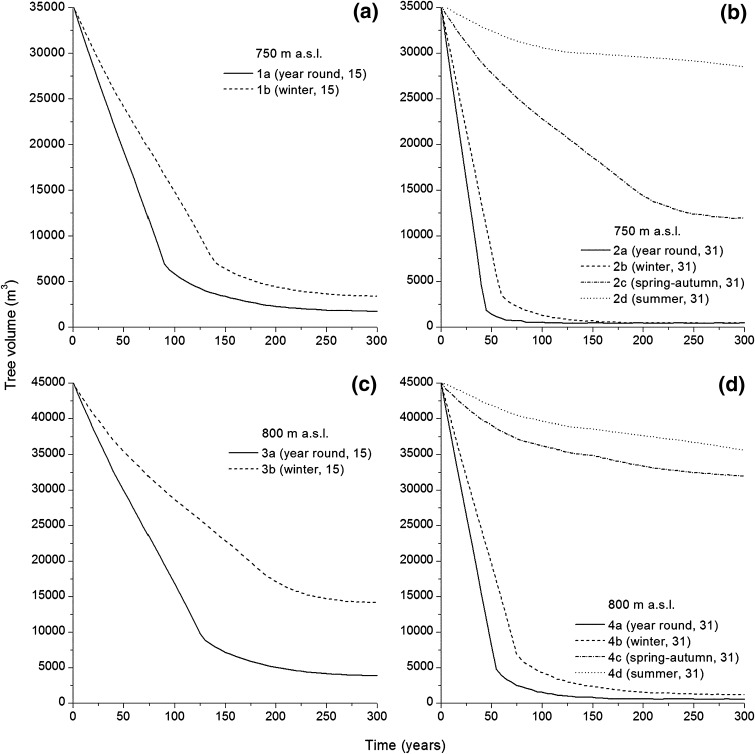

All modeled scenarios resulted in a reduction of total tree volume over a 300-year period (Fig. 5a–d). Tree volumes were most rapidly reduced in the scenarios with year-round or winter occupation of all 31 stállo huts and a tree-line at 750 or 800 m a.s.l. (scenarios 2a, 2b, 4a, 4b, Fig. 5b, d). Within 45–130 years, the total tree volumes were reduced to c. 1800–3300 m3 (corresponding to ca. 2.6–3.6 m3 ha−1), less than the annual wood requirement for fuel and construction (cf. Table 2). Similarly, tree volume fell below this threshold (1800 m3 or c. 2.6 m3 ha−1) in scenario 1a (based on the lower habitation density, occupation year-round, and a tree-line at 750 m a.s.l.) after 250 years (Fig. 5a). Scenario 1b, with year-round occupation, low habitation density for 260 years, and a tree-line at 750 m a.s.l. resulted in a 90% reduction of tree volume (Fig. 5a), and Scenario 3a (with low habitation density, year-round occupation, and a tree-line at 800 m a.s.l.) also resulted in a 90% reduction in tree volume after 230 years (Fig. 5c). Tree cutting during winter with low habitation density and a 800 m a.s.l. tree-line (scenario 3b), or every season except winter with high habitation density and either 750 or 800 m a.s.l. tree-lines (scenarios 2c–d and 4c–d), reduced the tree volume moderately or weakly (Fig. 5b–d).

Fig. 5.

Simulated standing tree volume (m3) at 5-year intervals for scenarios 1a–b (a) and 2a–d (b) based on an initial tree-line elevation at 750 m a.s.l., 3a–b (c), and 4a–d (d) based on an initial tree-line elevation at 800 m a.s.l

Differences in N contents in soil, biomass, and vegetation

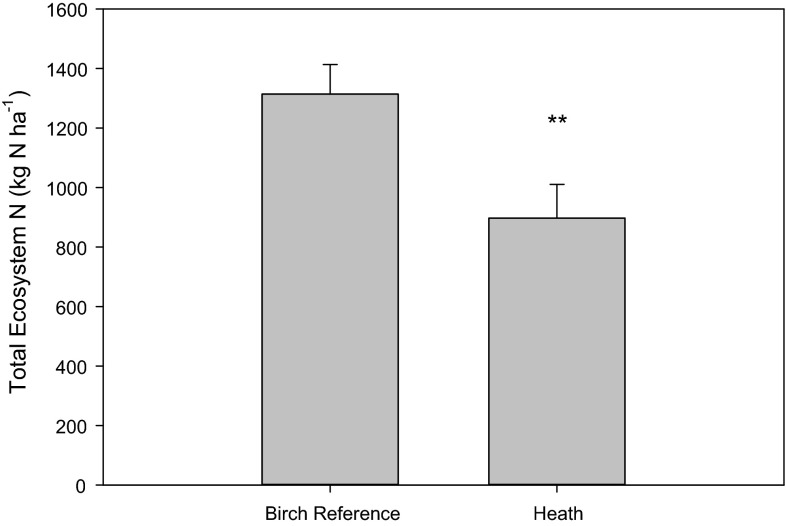

Replicate measurements of soil N pools demonstrated little difference in total N content between the Adjevaratj reference birch forest and the heathland soils at Adamvalta, as most of the N is held within the mineral soil (which is similar in both systems). However, total N in the birch forest was found to be significantly greater than that in the heathland ecosystems (1314 and 896 kg N ha−1, respectively, P < 0.01)—largely due to differences in N contents of the above-ground vegetation (trees and shrubs) and humus layer (Fig. 6). It should also be noted that N demand is far higher in the birch forest than in the heathland. Annual leaf biomass production in the birch forest was estimated at 165 g m−2 y−1, equivalent to about 33 kg N ha−1 y−1 in the leaves alone, assuming an N content of 20 g kg−1. With a further 3.7 kg N ha−1 y−1 in stems and growth increment, this results in a total N demand of 36.7 kg N ha−1 y−1 for above-ground parts of the birch trees. Understory biomass in the plots was found to amount to 7110 kg ha−1. Thus, assuming that 40% of the biomass is produced annually and has 15 g N kg−1, we estimate total understory N consumption at 42.7 kg N ha−1 y−1. Hence, the birch forest would consume c. 77.4 kg N ha−1 y−1, most of which would be recycled via reabsorption and litterfall.

Fig. 6.

Total ecosystem N (kg N ha−1 soil) of summed mineral soil N, humus N, and vegetative pools of N for the Adjevaratj reference birch forest and for heathland in Adamvalta. Asterisks (**) indicate significance at P < 0.01 using a two tailed T test (n = 3, paired sites with five replicates per site)

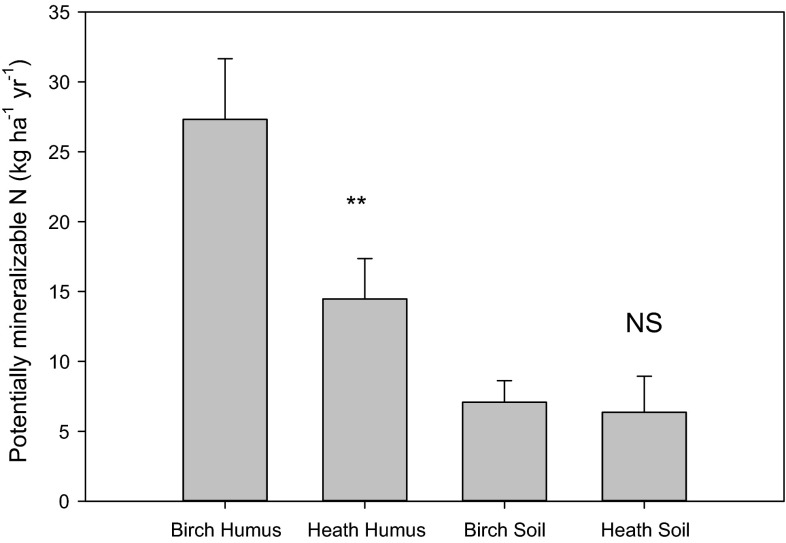

In contrast, total biomass in the heathland plots was found to be just 631 kg biomass ha−1, with an average N content of 6.9 g kg−1 ha−1 (due to the greater domination by woody stems) or a total of 47.8 kg N ha−1 in biomass. Assuming 40% annual turnover, this results in a total N requirement of 19.1 kg N ha−1 y−1, fourfold lower than the birch forest’s demand. This is supported by the significantly (P < 0.05) higher mineralizable N content observed in birch forest soils (over 27 kg PMN ha−1) compared with heathland soils (<15 kg PMN ha−1) (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Comparison of potentially mineralizable N (kg N ha−1) in humus and soil from the Adjevaratj reference birch forest and the heathland at Adamvalta. Asterisks (**) indicate significance at P < 0.01 using a two tailed T test (n = 8, paired sites with eight replicates per site)

Discussion and interpretation

Areas such as the Adamvalta Valley are anomalous in the Scandinavian mountain range. The lower part of this valley lies at an altitude that is well below the regional tree-line but there is no mountain birch forest. It has clusters of archeological monuments with hearths where people have burnt birch wood (Hellberg 2004; Liedgren et al. 2007). Today, the closest patch of mountain birch forest is situated c. 5 km from these settlement remains. The local pollen and charcoal records show that dramatic vegetation changes occurred during the settlement phase and indicate that the initial forest gave way to the open landscape of heathland that we see today (Karlsson et al. 2007). The fundamental sequences of events, and their timing, are not contested here but we seek to elucidate the mechanisms underlying the deforestation and assess the likelihood that it was caused by people’s use of the mountain birch.

Importance of habitation density, habitation period, and tree-line altitude

Our simulations indicate that cutting mountain birch trees for fuel and wooden constructions could have deforested the Adamvalta Valley within a timeframe corresponding to the settlement period, AD 800–1050, supporting the hypothesis that deforestation events have occurred during pre-historic times in the Scandinavian mountain range (see Hellberg 2004; Karlsson et al. 2009; Staland et al. 2011). The most rapid deforestation occurred in scenarios 2a, 2b, 4a, and 4b, simulating year-round or winter occupation of all 31 stállo huts (Fig. 5b, d). In these scenarios, the tree volume decreased from almost 50 m3 ha−1 to c. 2.6–3.6 m3 ha−1 in just 45–130 years, a substantially shorter timeframe than the c. 200–300 years suggested by Karlsson et al. (2007), and within the range of the estimated settlement period. Moreover, scenario 1a (with year-round, low habitation density, and a 750 m tree-line altitude) also led to deforestation within 260 years (Fig. 5a). Interestingly, the scenarios simulating occupation during spring, summer, and autumn or only during summer had weak to moderate effects on the standing tree volumes and did not lead to deforestation. Thus, we suggest that the habitation period rather than habitation density and/or tree-line altitude was the most influential factor affecting the Adamvalta Valley’s deforestation.

The stállo foundations are among the most prominent archeological monuments in the Scandinavian mountain range. Despite extensive previous research, their economic and cultural contexts remain obscure. Whether the people who built the stállo foundations based their economy on hunting wild reindeer, as suggested by Mulk (1994), or on herding reindeer, as proposed by Storli (1994) and Liedgren and Bergman (2009), remains unclear. There are also disagreements regarding the structural design of the stállo buildings and the time(s) of year they were occupied. The type of construction has been interpreted as representing either permanent buildings (Liedgren and Bergman 2009) or foundations for temporary raised tents (Mulk 1994; Storli 1994). Our simulation approach clearly supports the proposition by Liedgren and Bergman (2009) that the settlements were occupied year-round or at least during the winter. The annual and winter wood consumption per stállo hut used in our modeling included estimates for both fuel wood and construction wood (estimated at 4 m3 year−1). However, the key driver of the dramatic reductions in tree volumes was presumably heavy cutting for fuel wood (Fig. 5a, b, d), a necessity for surviving the long, cold winters in the mountain areas (Liedgren and Östlund 2011).

Deforestation and its long-term ecosystem effects

Ecosystems can be affected by dramatic regime shifts (Scheffer and Carpenter 2003). High-latitude ecotones are especially susceptible to environmental or climatic change and can shift to alternative stable states after large-scale disturbances (Larsen 1989). For example, Arseneault and Payette (1997) found evidence of severe losses of black spruce [Picea mariana (Mill.) Britton, Sterns & Poggenb.] forest in peatlands close to the Arctic tree-line in northern Québec, Canada, following forest fire disturbance. This shift from a forest to a tundra landscape highlights the sensitivity of subarctic forest ecosystems. In the Scandinavian mountain range, however, fire events are extremely rare due to low probability of lightning strikes (Granström 1993), high humidity, low temperature, and a short vegetation period (http://www.smhi.se/klimatdata). There were no peaks in the fossil charcoal records established by Karlsson et al. (2007), which would indicate large fire events, and the charred particles were too few to correspond to a substantial reduction of the tree cover. Rather, this fossil charcoal seems to derive from fires made in the huts as indicated by experimental studies of charcoal dispersal in this area (see Hörnberg and Liedgren 2012). Furthermore, a single fire event might cause deforestation, but regeneration follows as a result of the fact that only about half of the N is lost from the O horizon in a single fire event (unless it is unusually severe) and basically none is lost from the surface mineral soils (Smithwick et al. 2005). Accordingly, it takes multiple return events to degrade the nutrient base (DeLuca and Sala 2006). We believe that the Adamvalta Valley was deforested through extensive tree cutting within less than 260 years (as indicated by our simulations), and previous studies have shown that mountain birch forest has been transformed into alpine heath at several locations in the Scandinavian mountain range (Karlsson et al. 2007, 2009; Staland et al. 2011).

Our study illuminates the mechanisms behind such anthropogenic deforestation events, but the reason why no trees have regenerated after such large-scale disturbances is still unclear. However, the results obtained in this study and from other studies of various subarctic ecosystems suggest that the following processes, including loss of the nitrogen-fixing feathermoss–Nostoc complexes, may explain the changes detected in Adamvalta. Both subarctic forests and alpine heaths are generally nitrogen-limited, but the latter also experience available phosphorus deficiencies (Soudzilovskaia and Onipchenko 2005). Nitrogen is introduced to the ecosystem via epiphytic cyanobacteria that live in the leaf incurves of the dominant feathermosses and reduce N2 gas to ammonia, some of which is used by the mosses and ultimately converted to organic soil nitrogen (DeLuca et al. 2002; Zackrisson et al. 2009). This process builds up the total N content in sub-alpine birch forests but not in alpine heathlands where feathermosses are generally absent (Fig. 6). As fuel wood became scarcer due to deforestation, the local residents may have resorted to harvesting low-growing woody shrubs during winter months, but when all wood resources had been depleted, the local conditions changed dramatically as solar radiation and surface wind speeds increased. Such environmental changes, probably in combination with reindeer trampling and grazing, resulted in drier conditions and humus and soil erosion during summer, while the stronger winds reduced the snow cover and promoted deeper ground frosts in winters (cf. Arseneault and Payette 1997). The dry, exposed soil surfaces with reduced tree cover were less suitable for feathermosses (Wookey and Robinson 1997), leading to reductions in nitrogen-fixing rates and lower N content in humus (Fig. 7). This development gradually changed the sub-alpine birch forest ecosystem surrounding the stállo settlements into an alpine heath, and eventually the deforested area was abandoned due to the lack of fuel wood, and according to Bergman et al. (2013), persistent ecosystem degradations necessitated shifts in land use toward more flexible and sustainable strategies.

Nevertheless, single trees or small patches of forest may still have been present in the Adamvalta Valley that could have served as seed sources for tree regeneration. However, around AD 1300, the climate deteriorated and remained harsher for several centuries (i.e., LIA, see Campbell and McAndrews 1993), substantially reducing successful tree regeneration throughout the Scandinavian mountain range (Osborn and Briffa 2006). Some free-laying hearths date to the LIA in the Adamvalta Valley, showing that it was used occasionally by people during this period (Liedgren et al. 2007). Presumably, the few trees and shrubs that were still present were used as fuel wood by these people. Furthermore, as vegetation re-establishment was hindered for a long time due to the harsh climate, soil nutrient depletion was not countered by plants. Hence, the area remained open for a long time due to a sequences of events driven by several interacting factors, including tree cutting, browsing and trampling by herbivores, loss of N2 fixing feathermoss–Nostoc associations, climate change, and most likely nutrient depletion through leaching, leading to long-term degeneration of the alpine heath.

A similar ecosystem shift has been detected in other parts of northernmost Sweden, where patches of dense mixed coniferous forests on sedimentary soils were transformed into open degenerated spruce forests (DeLuca et al. 2013). This degeneration probably resulted from recurrent anthropogenic fires followed by climatic deterioration (during the LIA) and herbivore trampling and grazing, all of which negatively affected tree regeneration and ecosystem productivity. Our results demonstrate that the heathland has lost a great deal of nitrogen, compared to the reference forest (Fig. 6), even though most of the nitrogen resides in the mineral soil in both systems and did not readily influenced shifts in vegetative community (Fig. 7). Furthermore, the birch forest requires nearly four times more nitrogen than the heathland, and could probably not be sustained by the limited nitrogen resources in the heathland surface soil.

Modeling deforestation in local and wider perspectives

Modeling present and future forest composition and landscape patterns as functions of climate, disturbance regime, and land use can be highly valuable for testing hypotheses and enhancing understanding of various aspects of landscape ecology and ecosystem changes (see Scheller and Mladenoff 2007). Despite their value, there have been few simulations of forest changes under pre-historic conditions, but notable exceptions include the following. Berland et al. (2011) simulated long-term ecosystem changes, and then compared model outputs with empirical paleoecological vegetation data to identify key drivers of vegetation dynamics in the Big Woods region in Minnesota, USA. Scheller et al. (2008) modeled forest changes in the New Jersey Pine Barrens, USA, under pre-colonial conditions to construct scenarios mimicking a pre-colonial landscape. Both of these studies demonstrated the value of spatial simulation modeling for elucidating ecosystem changes and landscape history. Further, quantitative reconstructions of past regional plant abundance (Sugita 2007) or of fluctuating tree-lines (von Stedingk and Fyfe 2009) based on fossil pollen data may also be useful for this purpose.

In this study, we used the Heureka DSS as a framework to model a deforestation event during pre-historical times when the forest was primarily used as a source of fuel wood. The Heureka DSS is primarily designed for forestry planning and analysis of forest development in productive forest areas. However, it is capable of handling detailed (single-tree) forest inventory data, simulates cuttings, predicts forest development over long time horizons, and includes a built-in problem solver permitting simulations of scenarios under diverse assumptions. Thus, it is also highly appropriate for purposes such as those in the present study, provided that growth projections can be calibrated to the case study area.

Anthropogenic deforestation (temporary or permanent) such as that studied here is thought to be rather unusual in boreal and subarctic ecosystems, and thus little researched. An important exception includes Trbojevic et al. (2012), who studied fuel-wood consumption in a full-scale replica of a Icelandic Viking Age house, and found that so large quantities of fuel wood were required to fulfill the daily household needs that woodland management is likely to have been widespread to prevent deforestation. Also other studies from Iceland and Greenland, in relatively similar settings and during approximately the same time period, have likewise shown intense impact on birch forests but also suggested that early active forest management may have increased survival and regeneration of the forest to prevent rapid deforestation (Simpson et al. 2003; Dugmore et al. 2007; Schofield and Edwards 2011). To what extent the people inhabiting the Adamvalta Valley tried to manage the birch forest is unclear. Was this resource exhausted or did the intense and prolonged tree cutting trigger an unstoppable process which eventually led to complete deforestation? Mountain birch is not a limiting resource at the landscape level in this region, and therefore not a critical factor for the location of the settlement. The Adamvalta Valley was most certainly important for the use of other resources, presumably related to reindeer. This is indicated by repeated use during several centuries and the establishment of permanent constructions (cf. Bergman et al. 2008). At a certain point, mountain birch became too scarce to sustain the settlements with fuel wood, which triggered people to abandon the valley. We speculate therefore that the forest resource was exploited, eventually exhausted and not managed.

Conclusions

The approach presented in this study improves our understanding of the mechanisms behind tree-line dynamics and large-scale ecosystem transformations caused by people during pre-historical times. Our results indicate that cutting mountain birch trees for fuel and wooden constructions may have deforested an entire mountain valley within just a few hundred years, and that the habitation period rather than habitation density was the most influential factor affecting the deforestation. Re-establishment of trees was then prevented through a complex interaction between degeneration, nutrient depletion, and elimination or gross reduction of plant species that facilitate biological N2 fixation. This study, together with similar studies from a wide range of ecosystems indicates that deforestation during pre-historical times could be both dramatic and persistent under certain conditions and caused by temporally limited but intensive human land use. Presumably, ecosystem boundaries (e.g., the ecotone where sub-alpine forest transcends to alpine heath) are especially vulnerable to this process. In this perspective, we challenge the common view of the Scandinavian mountain range as being the last remaining wilderness in Europe.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank two anonymous reviewers for useful comments on earlier versions of the manuscript. The English has been corrected by Sees-Editing, UK. This study was financially supported by the Bank of Sweden Tercentenary Fund and the Swedish Environmental Protection agency and their Mountain Research Program.

Biographies

Lars Östlund

is a Professor at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. His research interests include historical ecology with special focus on forest history.

Greger Hörnberg

is an Associate Professor at the Institute for Subarctic Landscape Research. His research interests include vegetation history.

Thomas H. DeLuca

is a Director and Professor at the School of Environmental and Forest Sciences at the University of Washington. As a forest soil scientist and an ecosystem ecologist, his primary research interests include the influence of disturbance on N and C cycling in forest, fire ecology of temperate and boreal forests, biological N2 fixation in forest ecosystems, sustainable forest management, and evaluation of anthropogenic impacts on soils and ecosystems.

Lars Liedgren

is a researcher at the Institute for Subarctic Landscape Research. His research interests include archeology, experimental archeology, ethnology, and history in boreal and alpine areas from Stone Age up to modern times.

Peder Wikström

is a former researcher at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences and holds a PhD in forest management planning. He now works on a consultancy basis. His research interests include forest planning and optimization in a multi-criteria decision context.

Olle Zackrisson

is a Professor at the Institute for Subarctic Landscape Research and at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. His research interests include forest history and vegetation ecology.

Torbjörn Josefsson

is a researcher at the Institute for Subarctic Landscape Research and at the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences. His research interests include historical ecology with special focus on forest history and vegetation ecology in boreal and subarctic ecosystems.

Contributor Information

Lars Östlund, Email: lars.ostlund@slu.se.

Greger Hörnberg, Email: greger.hornberg@silvermuseet.se.

Thomas H. DeLuca, Email: deluca@uw.edu

Lars Liedgren, Email: lars.liedgren@silvermuseet.se.

Peder Wikström, Email: peder@pwskogsanalys.se.

Olle Zackrisson, Email: olle.zackrisson@silvermuseet.se.

Torbjörn Josefsson, Phone: +46 90 70 615 2621, Email: torbjorn.josefsson@slu.se.

References

- Arseneault D, Payette S. Landscape change following deforestation at the Arctic tree line in Québec, Canada. Ecology. 1997;78:693–706. [Google Scholar]

- Bedward M, Simpson CC, Ellis MV, Metcalfe LM. Patterns and determinants of historical woodland clearing in central-western New South Wales, Australia. Geographical Research. 2007;45:348–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-5871.2007.00474.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman I, Liedgren LG, Östlund L, Zackrisson O. Kinship and settlements: Sami residence patterns in the Fennoscandian alpine areas around A.D. 1000. Arctic Anthropology. 2008;45:97–110. doi: 10.1353/arc.0.0005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bergman I, Zackrisson O, Liedgren L. From hunting to herding: Land use, ecosystem processes, and social transformation among Sami AD 800–1500. Arctic Anthropology. 2013;50:25–39. doi: 10.3368/aa.50.2.25. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berland A, Shuman B, Manson S. Simulated importance of dispersal, disturbance, and landscape history in long-term ecosystem change in the big woods of Minnesota. Ecosystems. 2011;14:398–414. doi: 10.1007/s10021-011-9418-x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brandel G. Volume functions for individual trees. Garpenberg: Department of Forest Yield Research; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Briggs JM, Spielmann KA, Schaafsma H, Kintigh KW, Kruse M, Morehouse K, Schollmeyer K. Why ecology needs archaeologists and archaeology needs ecologists. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 2006;4:180–188. doi: 10.1890/1540-9295(2006)004[0180:WENAAA]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell ID, McAndrews JH. Forest disequilibrium caused by rapid Little Ice-Age cooling. Nature. 1993;366:336–338. doi: 10.1038/366336a0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Carlsson, B.Å., P.S. Karlsson, and B.M. Svensson. 1999. Alpine and subalpine vegetation. In Swedish plant geography. Acta Phytogeographica Suecica 84, ed. H. Rydin, P. Snoeijs, and M. Diekmann, 75–89. Uppsala: Almqvist & Wiksell.

- DeLuca TH, Zackrisson O, Nilsson MC, Sellstedt A. Quantifying nitrogen-fixation in feather moss carpets of boreal forests. Nature. 2002;419:917–920. doi: 10.1038/nature01051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLuca TH, Sala A. Frequent fire alters nitrogen transformations in ponderosa pine stands of the inland northwest. Ecology. 2006;87:2511–2522. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2006)87[2511:FFANTI]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLuca TH, Zackrisson O, Bergman I, Hörnberg G. Historical land use and resource depletion in spruce-Cladina forests of subarctic Sweden. Anthropocene. 2013;1:14–22. doi: 10.1016/j.ancene.2013.03.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dugmore AJ, Church MJ, Mairs K-A, McGovern TH, Perdikaris S, Vésteinsson O. Abandoned farms, volcanic impacts, and woodland management: Revisiting Þjórsárdalur, the “Pompeii of Iceland”. Arctic Anthropology. 2007;44:1–11. doi: 10.1353/arc.2011.0021. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Elfving B. Ålderstilldelning till enskilda träd i skogliga tillväxtprognoser [Age assignment of individual trees in growth prognoses] Umeå: Department of Silviculture, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Granström A. Spatial and temporal variation in lightning ignitions in Sweden. Journal of Vegetation Science. 1993;4:737–744. doi: 10.2307/3235609. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harris DR. The origins and spread of agriculture and pastoralism in Eurasia. Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Hellberg, E. 2004. Historical variability of deciduous trees and deciduous forests in northern Sweden: Effects of forest fires, land-use and climate. Doctoral diss., Department of Forest Vegetation Ecology, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences.

- Hughes JD. Ancient deforestation revisited. Journal of the History of Biology. 2011;44:43–57. doi: 10.1007/s10739-010-9247-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hörnberg G, Liedgren L. Charcoal dispersal from alpine Stállo hearths in sub-arctic Sweden: Patterns observed from soil analysis and experimental burning. Asian Culture and History. 2012;4:29–42. doi: 10.5539/ach.v4n2p29. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan JO, Krumhardt KM, Zimmermann N. The prehistoric and preindustrial deforestation of Europe. Quaternary Science Reviews. 2009;28:3016–3034. doi: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2009.09.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson H, Hörnberg G, Hannon G, Nordström EM. Long-term vegetation changes in the northern Scandinavian forest limit: A human impact-climate synergy? The Holocene. 2007;17:37–49. doi: 10.1177/0959683607073277. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsson H, Shevtsova A, Hörnberg G. Vegetation development at a mountain settlement site in the Swedish Scandes during the late Holocene: Palaeoecological evidence of human-induced deforestation. Vegetation History and Archaeobotany. 2009;18:297–314. doi: 10.1007/s00334-008-0207-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kullman L. 20th century climate warming and tree-limit rise in the southern Scandes of Sweden. AMBIO. 2001;30:72–80. doi: 10.1579/0044-7447-30.2.72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, J.A. 1989. The northern forest border in Canada and Alaska: Biotic communities and ecological relationships. Ecological Studies 70. New York: Springer, 255 pp.

- Lev-Yadun S, Lucas DS, Weinstein-Evron M. Modeling the demands for wood by the inhabitants of Masada and for the Roman siege. Journal of Arid Environments. 2010;74:777–785. doi: 10.1016/j.jaridenv.2010.01.010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liedgren L, Bergman I. Aspects of the construction of prehistoric Stállo-foundations and Stállo-buildings. Acta Borealia. 2009;26:3–26. doi: 10.1080/08003830902951516. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liedgren LG, Bergman I, Hörnberg G, Zackrisson O, Hellberg E, Östlund L, DeLuca TH. Radiocarbon dating of prehistoric hearths in alpine northern Sweden: Problems and possibilities. Journal of Archaeological Science. 2007;34:1276–1288. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2006.10.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liedgren LG, Östlund L. Heat, smoke and fuel consumption in a high mountain stállo-hut, northern Sweden: Experimental burning of fresh birch wood during winter. Journal of Archaeological Science. 2011;38:903–912. doi: 10.1016/j.jas.2010.11.020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McWethy DB, Whitlock C, Wilmshurst JM, McGlone MS, Fromont M, Li X, Dieffenbacher-Krall A, Hobbs WO, Fritz SC, Cook ER. Rapid landscape transformation in South Island, New Zealand, following initial Polynesian settlement. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:21343–21348. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1011801107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moen J. Climate change: Effects on the ecological basis for reindeer husbandry in Sweden. AMBIO. 2008;37:304–311. doi: 10.1579/0044-7447(2008)37[304:CCEOTE]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulk, I.M. 1994. Sirkas: A Sami hunting society in transition AD 1–1600. Doctoral diss., Department of Archaeology, University of Umeå.

- Osborn TJ, Briffa KR. The spatial extent of 20th-century warmth in the context of the past 1200 years. Science. 2006;311:841–844. doi: 10.1126/science.1120514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheffer M, Carpenter SR. Catastrophic regime shifts in ecosystems: Linking theory to observation. Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 2003;18:648–656. doi: 10.1016/j.tree.2003.09.002. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scheller RM, Mladenoff DJ. An ecological classification of forest landscape simulation models: Tools and strategies for understanding broad-scale forested ecosystems. Landscape Ecology. 2007;22:491–505. doi: 10.1007/s10980-006-9048-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Scheller RM, Van Tuyl S, Clark K, Hayden NG, Hom J, Mladenoff DJ. Simulation of forest change in the New Jersey Pine Barrens under current and pre-colonial conditions. Forest Ecology and Management. 2008;255:1489–1500. doi: 10.1016/j.foreco.2007.11.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schofield JE, Edwards K. Grazing impacts and woodland management in Eriksfjord: Betula, coprophilous fungi and the Norse settlement of Greenland. Vegetation History and Archaeobotany. 2011;20:181–197. doi: 10.1007/s00334-011-0281-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shackleton CM, Prins F. Charcoal analysis and the principle of least effort: A conceptual model. Journal of Archaeological Science. 1992;19:631–637. doi: 10.1016/0305-4403(92)90033-Y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson IA, Vésteinsson O, Adderley WP, McGovern TH. Fuel resource utilisation in landscapes of settlement. Journal of Archaeological Science. 2003;30:1401–1420. doi: 10.1016/S0305-4403(03)00035-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smithwick EAH, Turner MG, Mack MC, Chapin FS. Postfire soil N cycling in northern conifer forests affected by severe, stand-replacing wildfires. Ecosystems. 2005;8:163–181. doi: 10.1007/s10021-004-0097-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Soudzilovskaia NA, Onipchenko VG. Experimental investigation of fertilization and irrigation effects on an alpine heath, northwestern Caucasus, Russia. Arctic, Antarctic, and Alpine Research. 2005;37:602–610. doi: 10.1657/1523-0430(2005)037[0602:EIOFAI]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Staland H, Salmonsson J, Hörnberg G. A thousand years of human impact in the northern Scandinavian mountain range: Long-lasting effects on forest lines and vegetation. The Holocene. 2011;21:379–391. doi: 10.1177/0959683610378882. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Storli, I. 1994. “Stallo”-boplassene: spor etter de første fjellsamer? [“Stallo” settlements: Traces of the first mountain Sami?]. Oslo: Novus, 141 pp.

- Sugita S. Theory of quantitative reconstruction of vegetation II: All you need is LOVE. The Holocene. 2007;17:243–257. doi: 10.1177/0959683607075838. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Söderberg, U. 1992. Functions for forest management. Height, form height and bark thickness of individual trees. Report 52. Umeå: Department of Forest Survey, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences.

- Trbojevic N, Mooney DE, Bell AJ. A firewood experiment at Eiríksstaðir: A step towards quantifying the use of firewood for daily household needs in Viking Age Iceland. Archaeologia Islandica. 2012;9:29–40. [Google Scholar]

- Wielgolaski FE, Karlsson PS, Neuvonen S, Thannheiser D. Plant ecology, herbivory, and human impact in Nordic mountain birch forests. Berlin: Springer; 2005. p. 365. [Google Scholar]

- Wikström P, Edenius L, Elfving B, Eriksson LO, Lämås T, Sonesson J, Öhman K, Wallerman J, Waller C, Klintebäck F. The Heureka forestry decision support system: An overview. Mathematical and Computational Forestry and Natural Resources Sciences. 2011;3:87–94. [Google Scholar]

- Williams M. Deforesting the earth: From prehistory to global crisis. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- von Stedingk H, Fyfe RM. The use of pollen analysis to reveal Holocene treeline dynamics: A modelling approach. The Holocene. 2009;19:273–283. doi: 10.1177/0959683608100572. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wookey PA, Robinson CH. Responsiveness and resilience of high Arctic ecosystems to environmental change. Opera Botanica. 1997;132:215–232. [Google Scholar]

- Zackrisson O, DeLuca TH, Gentili F, Sellstedt A, Jaderlund A. Nitrogen fixation in mixed Hylocomium splendens moss communities. Oecologia. 2009;160:309–319. doi: 10.1007/s00442-009-1299-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.