Abstract

Micafungin is an echinocandin with potent activity against a broad range of fungal species, including Candida species. The pharmacokinetic and safety profiles of micafungin have been evaluated in individuals with mild-to-moderate hepatic dysfunction, but not in individuals with severe hepatic dysfunction. Therefore, the present study assessed the pharmacokinetics and safety of a single 100 mg dose of micafungin in healthy subjects (n = 8) and subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction (n = 8). Mean maximum plasma concentration of micafungin and mean area under the plasma micafungin concentration–time curve extrapolated to infinity were lower in subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction (7.3 ± 2.4 µg/mL and 100.1 ± 34.5 h·μg/mL, respectively) than in subjects with normal hepatic function (10.3 ± 2.5 µg/mL and 142.4 ± 28.9 h·μg/mL, respectively). Mean clearance was higher in subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction (1,098 ± 347 mL/h) than in subjects with normal hepatic function (728 ± 149 mL/h). Concentrations of albumin in subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction were lower. Assessments of micafungin plasma protein binding suggested that the higher clearance in subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction may be due to higher unbound concentrations. However, the magnitude of the differences was not considered clinically meaningful and is comparable with exposures reported elsewhere for a 100-mg dose in patients treated for invasive candidiasis. Thus, dose adjustment in subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction is not warranted. Micafungin was well tolerated in all subjects throughout the study.

Keywords: Hepatic, Liver, Micafungin, Pharmacokinetics, Safety

Introduction

Candidaemia and invasive candidiasis are the most common invasive fungal infections, and the incidence of these serious diseases is rising (Pfaller and Diekema 2007). In Europe, Candida albicans is responsible for >50 % of cases of invasive candidaemia; however, non-albicans-related Candida infections are also increasing (Lass-Flörl 2009).

Micafungin is an injectable echinocandin antifungal agent that displays potent activity against a broad range of Candida species (Jarvis et al. 2004; Messer et al. 2006). It has demonstrated efficacy similar to that of liposomal amphotericin B and caspofungin for the treatment of invasive candidiasis and candidaemia (Kuse et al. 2007; Pappas et al. 2007) and to that of fluconazole for the treatment of oesophageal candidiasis (de Wet et al. 2005). Moreover, it exhibits superior efficacy and comparable safety to fluconazole for the prophylaxis of invasive fungal infections in patients undergoing haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (van Burik et al. 2004).

Micafungin is metabolised in the liver and is mainly excreted in bile (Fromtling 2002); it undergoes metabolism to three metabolites: M-1, formed by metabolism of the parent drug; M-2, formed by degradation of M-1; and M-5, formed by hydroxylation of the side chain of micafungin by CYP450 enzymes. However, metabolism by the CYP450 system plays only a minor role in the degradation of micafungin (Wiederhold and Lewis 2007).

Previous pharmacokinetic (PK) studies of micafungin have been conducted in healthy adults (Hebert et al. 2005a, b, c; Keirns et al. 2007), HIV-positive adults with confirmed oesophageal candidiasis (Undre et al. 2012a), adults and children with invasive candidiasis and candidaemia (Undre et al. 2012b, c), neonates with suspected candidaemia or invasive candidiasis (Benjamin et al. 2010) and subjects with mild-to-moderate hepatic dysfunction (Hebert et al. 2005b). The recommended daily dose for the treatment of adults with invasive candidiasis and candidaemia is 100 mg. This results in the following mean steady-state PK parameters: area under the plasma concentration–time curve over dosage time interval 0–24 h (AUC0–24), 97 h·μg/mL; maximum plasma concentration (C max), 10.5 μg/mL; clearance (CL), 1,168 mL/h and half-life (t ½), 14–15 h (Undre et al. 2012b).

In a study in subjects with moderate hepatic dysfunction (Child–Pugh score 7–9), AUC extrapolated to infinity (AUC∞) and C max of micafungin were lower, and CL higher, compared with healthy subjects, but the differences were not considered to be clinically relevant (Hebert et al. 2005b). Exposure was comparable with that observed for a 100-mg dose in patients treated for invasive candidiasis (Undre et al. 2012b). Thus, dose adjustment was not considered necessary in subjects with mild-to-moderate hepatic dysfunction. However, there are no data on the PK and safety of micafungin in individuals with severe hepatic dysfunction. Therefore, this study was designed to characterise the PK and safety profiles of micafungin following administration of a single dose of 100 mg to individuals with severe hepatic dysfunction.

Methods

Subjects and study design

This was a single-dose, open-label study in which subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction (Child–Pugh score 10–12) and healthy, control subjects were enrolled and matched 1:1 for age (within 10 years), weight (within 20 %), sex and race. All subjects were aged between 18 and 75 years and within 35 % of their ideal body weight. Subjects were excluded from the study if they had received any prescribed systemic or topical medication within 14 days of receiving study drug, non-prescribed systemic or topical medication within 7 days (except vitamin or mineral supplements or paracetamol or contraceptives in healthy females) or any medications known to chronically alter drug absorption or elimination within 30 days. Subjects were also excluded if they had participated in a clinical study of a drug within the previous month, had a known history of lactose or gluten intolerance, clinically significant allergic disease, other significant illness within 3 months of the start of the study, multiple drug allergies or allergy to the micafungin drug class, supine blood pressure and supine pulse rate at screening higher than 150/100 mmHg and 100 beats per min, respectively, or lower than 100/50 mmHg and 40 beats per min, respectively, positive drug screen, pregnancy test or test for HIV antibodies or clinically relevant coagulation abnormalities. In addition, any subjects with medical history or clinical or laboratory findings indicative of acute or chronic disease that, in the opinion of the investigator, might influence study outcome, a history of any clinically significant neurological, gastrointestinal, renal, hepatic, cardiovascular, psychiatric, respiratory, metabolic, endocrine, haematological or other major disorder (normal hepatic function), or an invasive infection that required treatment (severe hepatic dysfunction) were also excluded from the study.

Eligibility was assessed by physical examination, vital signs, 12-lead electrocardiogram, drug and alcohol screen, clinical laboratory parameters and medical history conducted ≤15 days before administration of study drug (Day 1) with confirmation of eligibility criteria on Day 1. On Day-1, all subjects received a single dose of micafungin 100 mg. All eligible subjects were hospitalised for the study period (Day-1 to Day 5).

Written, informed consent approved by the local independent ethics committee, the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Health Sciences of the University of the Free State and the South African Medicines Control Council was obtained from all participants prior to all study procedures. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles set forth in the Declaration of Helsinki as amended in Tokyo, 2004, and the Guidelines of the International Conference on Harmonization on Good Clinical Practice.

Chemicals and drugs

Micafungin was supplied in vials containing lyophilised micafungin powder 50 mg plus lactose 200 mg, together with 0.9 % sodium chloride solution for injection in 250 mL infusion bags.

Drug administration

On Day 1 each subject received a single infusion of micafungin 100 mg at a constant rate of 100 mL/h for 1 h, administered intravenously via a cannula. Each subject received a total of 100 mL of intravenous dosing solution. Subjects remained supine during the entire infusion period.

Blood sampling and assays

Blood samples (10 mL) were collected by venous puncture or indwelling cannula of a forearm vein or veins (opposite arm to that receiving the infusion) into sodium heparinized tubes at the following times: pre-dose (0 h), 0.5, 1 h (end of infusion), 1.25, 1.5, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, 16, 24, 36, 48, 60, 72 and 96 h after the start of the micafungin infusion.

Plasma samples were prepared by protein precipitation using acetonitrile. Samples were centrifuged within 30 min of collection at 3,000 rpm for 10 min at ~4 °C. For each sample, four aliquots of 0.5 mL of the resulting plasma fraction were prepared for PK analyses. The plasma concentrations of micafungin and its metabolites were determined using high-performance liquid chromatography with fluorescence detection following validated procedures (Groll et al. 2001; Yamato et al. 2002). The lower limit of quantification (LLOQ) of plasma micafungin and its metabolites M-1, M-2 and M-5 was 0.05 µg/mL.

In addition, two aliquots of plasma (1 mL each), from the blood samples collected 8 and 24 h after the start of infusion, were used for determination of micafungin plasma protein binding using an ultracentrifugation method. Protein-bound and unbound micafungin were separated using an ultrafiltration system (Centrifree® MPS-3, Millipore, Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany). Plasma samples were added to the filter reservoir of a micro-partition ultrafiltration device and centrifuged at 3,000 rpm for 15 min at 37 °C. The resulting ultrafiltrate was analysed for unbound micafungin levels. The ratio of unbound micafungin to total micafungin in plasma was calculated as ultrafiltrate concentration/plasma concentration.

PK analysis

The PK parameters determined for micafungin and its metabolites were C max, AUC0–24, AUC from time 0 to the last quantifiable concentration (AUClast), AUC∞, t ½, CL (micafungin only), volume of distribution (V z; micafungin only) and volume of distribution at steady state (V ss; micafungin only).

The C max was obtained directly from plasma micafungin concentration–time data. AUC0–24 and AUClast were calculated from the time of dosing to either the end of the dosing period or to the last measurable concentration of micafungin, respectively, by numeric integration using the linear trapezoidal rule for ascending concentrations and the log trapezoidal rule for descending concentrations, i.e.,

| 1 |

where n is the number of data points, are sampling times, and C i is plasma micafungin concentration from the sample at t i. AUC∞ was estimated using

| 2 |

where C t is the last measurable plasma concentration of micafungin and K e is the apparent terminal rate elimination constant obtained by log-linear regression of the terminal phase data. The t 1/2 values were defined using

| 3 |

Plasma CL were calculated using the following formula:

| 4 |

where F is the fraction of dose absorbed (which is presumed to be 1 as it was an IV infusion) and D is the dose amount. Apparent V z were calculated using

| 5 |

where C 0 is the extrapolated plasma micafungin concentration at time 0. Lastly, V ss was calculated as

| 6 |

where AUMC is the area under the first-moment curve.

Safety assessments

Subjects were monitored for adverse events (AEs) throughout the study. Additional safety evaluations comprised vital signs assessment, physical examination, 12-lead electrocardiograms, urinalysis and urine microscopy and clinical laboratory measurements.

Statistical analysis

The PK analysis set included all subjects with evaluable PK data who completed the study. The safety analysis set included all subjects who received micafungin treatment. Descriptive statistics were used to analyse subject demographics, laboratory measurements, vital signs and PK data. Log-transformed values of C max, AUC0–24, AUClast, AUC∞, t ½ and CL were analysed using an analysis of variance model with group as main effect using PROC MIXED of SAS (Version 8.2; SAS® Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA). The mean ratios and 90 % confidence intervals (CIs) for the mean differences on the logarithmic scale were transformed to obtain point estimates and 90 % CIs for the respective mean ratios. 90 % CIs in the acceptance range of 80–125 % were used to determine whether severe hepatic dysfunction altered the extent of micafungin exposure.

For subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction, multivariate linear regression analysis with stepwise selection was used to investigate the relationship between C max, AUC∞ and CL for each plasma analyte (micafungin, M-1, M-2 and M-5) and hepatic function explanatory parameters (i.e. Child–Pugh score, plasma albumin, total bilirubin, prothrombin time and international normalised ratio).

All analyses, including calculation of PK parameters, were conducted by a central laboratory (FARMOVS-PAREXEL, Bloemfontein, South Africa) using WinNonlin® Professional (Version 5.0.1, Pharsight Corporation, Mountain View, CA, USA).

Results

Subjects

Eight subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction and eleven subjects with normal hepatic function were included in this study. These 19 subjects comprised the safety analysis set. However, three of the subjects with normal hepatic function were excluded from the PK analysis due to protocol violations (involving processing of plasma aliquots from blood samples). Thus, the PK analysis set comprised the eight subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction and eight with normal hepatic function. Demographic characteristics of the study participants are shown in Table 1. Subjects were well matched for age, sex and body weight.

Table 1.

Subject demographics

| Subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction | Subjects with normal hepatic function | |

|---|---|---|

| Number of subjects (n) | 8 | 8 |

| Male, n (%) | 5 (62.5) | 5 (62.5) |

| Age, mean (SD), years | 54.5 (8.6) | 50.1 (6.3) |

| Weight, mean (SD) (kg) | 73.2 (20.2) | 70.2 (15.5) |

| Race, n (%) | ||

| White | 2 (25.0) | 2 (25.0) |

| Coloureda | 4 (50.0) | 0 |

| Mixed race | 2 (25.0) | 6 (75.0) |

SD standard deviation

aEthnic group as defined in a South African context

PK analysis

Mean plasma concentration versus time curves of micafungin in subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction and those with normal hepatic function are shown in Fig. 1. At each time point, the mean plasma micafungin concentration was lower in subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction compared with normal healthy subjects.

Fig. 1.

Plasma micafungin concentration versus time profiles (geometric mean ± SD) for subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction (n = 8) and normal hepatic function (n = 8)

A summary of the micafungin PK parameters obtained in subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction and healthy subjects is shown in Table 2. Mean C max, AUC0–24, AUClast and AUC∞ were lower in subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction compared with healthy subjects. The mean ratios for C max and AUC∞ were 69.2 % (90 % CI 51.3–93.5) and 68.2 % (90 % CI 50.8–91.5), respectively. However, mean CL, V z and V ss were higher in subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction compared with healthy subjects (mean ratio for CL was 146.7 % [90 % CI 109.3–196.8]), while mean t ½ was similar in both groups.

Table 2.

PK parameters of micafungin [geometric mean (SD)] in subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction and normal hepatic function

| Parameter | Subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction (n = 8) | Subjects with normal hepatic function (n = 8) | ANOVA results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ratio (%)a (90 % CI) | Coefficient of variation (%) | |||

| C max (µg/mL) | 7.3 (2.4) | 10.3 (2.5) | 69.2 (51.3–93.5) | 28.5 |

| AUC0–24 (h·μg/mL) | 71.6 (24.5) | 96.8 (20.7) | 72.0 (53.6–96.5) | 27.9 |

| AUClast (h·μg/mL) | 98.2 (34.3) | 140.6 (29.0) | 67.7 (50.4–91.1) | 28.2 |

| AUC∞ (h·μg/mL) | 100.1 (34.5) | 142.4 (28.9) | 68.2 (50.8–91.5) | 27.9 |

| t ½ (h) | 13.7 (2.1) | 14.9 (1.5) | 91.2 (79.5–104.5) | 12.8 |

| CL (mL/h) | 1,098 (347) | 728 (149) | 146.7 (109.3–196.8) | 27.9 |

| V z (mL) | 21,283 (5847) | 15,742 (3979) | NC | NC |

| V SS (L) | 19,903 (5670) | 14,693 (3351) | NC | NC |

ANOVA analysis of variance, NC not calculated

aLog-transformed mean value in subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction; log-transformed mean value in subjects with normal hepatic function

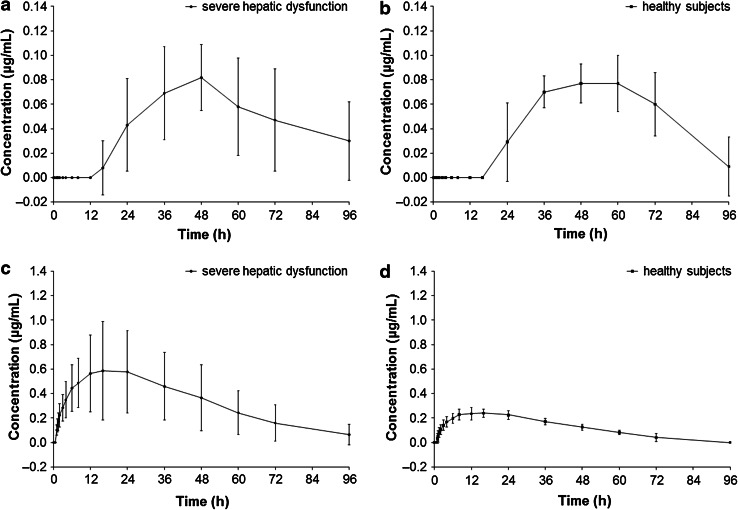

Mean plasma concentration versus time curves of the metabolites M-1 and M-5 are shown in Fig. 2. Plasma concentrations of M-2 were below LLOQ (0.05 µg/mL) at all time points; therefore, no PK parameters were derived for this metabolite. Plasma concentrations of M-1 metabolite were below LLOQ in all subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction at all time points ≤12 h post-dosing and in all but one subject with severe hepatic dysfunction at the 16-h post-dose time point. Plasma concentrations of the M-1 metabolite were also below LLOQ in all subjects with normal hepatic function at all time points up to 16 h post-dosing. From 24 h post-dosing, mean M-1 plasma concentrations were similar in both groups.

Fig. 2.

Plasma concentration versus time profiles (arithmetic mean ± SD) for the micafungin metabolites, M-1 (a, b) and M-5 (c, d), in subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction (n = 8) and normal hepatic function (n = 8)

For all subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction, plasma concentrations of M-5 metabolite were measurable from 1–75 h post-dosing, but below LLOQ for three of these subjects at the 96-h post-dose time point. For all healthy subjects, plasma concentrations of M-5 metabolite were measurable from 1.5–60 h post-dosing and below LLOQ at the 96-h post-dose time point. At all time points, mean M-5 metabolite plasma concentrations were higher in subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction compared with healthy subjects.

A summary of the PK parameters of the M-1 metabolite in subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction and in healthy subjects is shown in Table 3. Mean AUC∞ and t ½ were lower in subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction compared with healthy subjects. Point estimates for the ratios of AUC∞ and t ½ between the two groups were 79.5 % (90 % CI 44.9–140.8) and 70.0 % (90 % CI 29.4–166.5), respectively. Mean C max was similar in both groups.

Table 3.

PK parameters of micafungin metabolites, M-1 and M-5 [geometric mean (SD)], in subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction and normal hepatic function

| Parameter | Subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction (n = 8)a | Subjects with normal hepatic function (n = 8)a | ANOVA results | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ratio (%)b (90 % CIs) | Coefficient of variation (%) | |||

| Metabolite M-1 | ||||

| C max (µg/mL) | 0.1 (0.0) | 0.1 (0.0) | 102.2 (77.2–135.1) | 26.5 |

| AUC0–24 (h·μg/mL) | 0.2 (0.3) | 0.1 (0.1) | 133.5 (69.2–257.3) | 43.2 |

| AUClast (h·μg/mL) | 3.9 (2.6) | 3.5 (1.6) | 88.0 (38.7–199.7) | 89.2 |

| AUC∞ (h·μg/mL) | 13.1 (5.1) | 17.5 (11.9) | 79.5 (44.9–140.8) | 48.0 |

| t ½ (h) | 98.5 (69.6) | 154.0 (147.3) | 70.0 (29.4–166.5) | 78.2 |

| Metabolite M-5 | ||||

| C max (µg/mL) | 0.6 (0.4) | 0.2 (0.0) | 227.5 (155.2–333.5) | 36.8 |

| AUC0–24 (h·μg/mL) | 11.5 (6.4) | 4.9 (0.9) | 218.1 (153.3–310.2) | 33.8 |

| AUClast (h·μg/mL) | 31.0 (20.9) | 10.8 (1.7) | 251.2 (164.5–383.6) | 41.1 |

| AUC∞ (h·μg/mL) | 34.1 (23.4) | 12.9 (1.8) | 231.8 (152.3–352.7) | 40.7 |

| t ½ (h) | 21.1 (2.7) | 21.6 (4.9) | 99.1 (82.0–119.7) | 17.8 |

a n = 8 for all parameters except for AUC∞ and t 1/2 in subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction (n = 5), and for the ANOVA calculation of mean ratio of AUC0–24 (n = 4)

bLog-transformed mean value in subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction; log-transformed mean value in subjects with normal hepatic function

PK parameters for the M-5 metabolite in subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction and in subjects with normal hepatic function are summarised in Table 3. Mean C max, AUC0–24, AUClast and AUC∞ were higher in subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction compared with healthy subjects. Point estimates for the ratios of C max and AUC∞ were 227.5 % (90 % CI 155.2–333.5) and 231.8 % (90 % CI 152.3–352.7), respectively. However, the t ½ of M-5 was similar in both subject groups.

To examine a potential cause for the different PK profiles between the study groups, free plasma protein concentrations were evaluated in eight subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction and 11 healthy subjects. Mean serum albumin concentrations were lower in subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction [24.3 ± 7.1 g/L (Day 1), 22.6 ± 6.9 g/L (Day 2) and 24.3 ± 8.6 g/L (Day 5)] compared with healthy subjects [39.4 ± 2.1 g/L (Day-1), 36.5 ± 3.2 g/L (Day 2) and 38.5 ± 3.1 g/L (Day 5)].

Plasma protein binding of micafungin was assessed in all subjects but was only measurable in five subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction and three healthy subjects. The ratios of unbound plasma micafungin concentration (ultrafiltrate) to total plasma micafungin concentration ranged from 0.024 to 0.139 (86.1–97.6 % protein binding) in subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction and from 0.010 to 0.076 (92.4–99.0 % protein binding) in healthy subjects. Ultrafiltrate micafungin concentrations were below LLOQ in the remaining subjects.

Linear regression analyses, conducted to examine the relationships between PK parameters and hepatic measurements, revealed a trend toward a positive linear relationship between the CL of micafungin and Child–Pugh score (P = 0.0568), and positive linear relationships between both C max and AUC∞ of M-5 metabolite and total bilirubin (P < 0.05 in each).

Safety assessments

Safety was evaluated in eight subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction and eleven healthy subjects. Six AEs were reported by four subjects: one subject with severe hepatic dysfunction experienced dizziness and pruritus, and another experienced nausea and vomiting; while one healthy subject experienced headache and another experienced pruritus. None of these AEs was considered to be serious or to be related to micafungin, and none led to discontinuation of the study. No clinically significant changes in laboratory measures were reported at the end of study, including alanine aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, or bilirubin levels and prothrombin time.

Discussion

In this study, micafungin plasma concentrations and most PK parameters were lower in subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction, except for CL, which was higher in these subjects; however, the magnitude of the differences was not considered to be clinically meaningful. These findings are consistent with a previous study of micafungin, in which subjects with moderate hepatic dysfunction displayed lower C max and AUC values, but higher CL, compared with healthy subjects (Hebert et al. 2005b). Likewise, in a study of anidulafungin, there was a 33 % lower exposure in subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction compared with healthy controls (Dowell et al. 2007).

The recommended dose for the treatment of adults with invasive candidiasis and candidaemia in adults is 100 mg daily resulting in the mean steady-state AUC0–24 of 97 h·μg/mL (Undre et al. 2012b). In the present study, a dose of 100 mg yielded a mean AUC∞ of 100.1 h·μg/mL in subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction. These findings suggest that dose adjustment is not required in subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction.

Plasma concentrations of the M-1 metabolite were negligible in the first 24 h, suggesting a very slow rate of formation of this metabolite. For later time points, the plasma concentration profile of the M-1 metabolite was similar between the two study groups. Mean plasma concentrations of the M-5 metabolite, and its mean C max and AUC values, were higher and more variable in subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction compared with healthy subjects. This suggests that patients with severe hepatic impairment exhibit either a higher rate of formation or lower CL of M-5 compared with healthy subjects; however, it is unknown which mechanism is responsible for this observation. The PK of the M-1 and M-5 metabolites has not been examined in subjects with moderate hepatic dysfunction in previous studies.

As micafungin is metabolised in the liver prior to its elimination, exposure would be expected to be higher in subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction due to disrupted micafungin metabolism. However, the PK profiles obtained for micafungin and its metabolites suggest the opposite as micafungin exposure was higher in healthy subjects with normal hepatic function than in subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction.

Micafungin is highly protein bound in plasma (>99 %) (Astellas Pharma; Hebert et al. 2005b), primarily to albumin. Plasma albumin concentrations are often altered in the presence of severe hepatic dysfunction, raising the possibility that altered plasma albumin concentrations may have impacted micafungin PK in subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction (Hebert et al. 2005b). Consistent with this hypothesis, subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction in this study had lower concentrations of plasma albumin than subjects with normal hepatic function. This resulted in an increase in free drug levels in the subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction which, in turn, led to increased CL in these individuals. This may also explain why mean micafungin C max and AUC values were lower in subjects with hepatic dysfunction, but t ½ remained unchanged.

Micafungin is one of three available echinocandin antifungal agents. Existing evidence suggests that higher exposure to caspofungin is associated with moderate hepatic dysfunction and that this can be adjusted for using dose reduction (Merck Sharp & Dohme Limited 2011; Mistry et al. 2007; van der Elst et al. 2012). Anidulafungin is not metabolised by the liver, and, therefore, dose adjustments are not required in subjects with mild, moderate or severe hepatic dysfunction (Pfizer Inc 2010).

Although systemic exposure to micafungin was lower in subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction in this study, the magnitude of this difference was not considered clinically meaningful. Micafungin has demonstrated efficacy in adults with invasive candidiasis and candidaemia, and in adults with HIV and oesophageal candidiasis, at levels of exposure similar to those attained in the present study (Undre et al. 2012a, b). Furthermore, a comparison of the free concentration of micafungin in the two populations showed that the fraction unbound is similar in the two populations. Thus, despite lower total micafungin exposure, the free concentrations considered to be pharmacologically active were similar, suggesting that dose adjustments are not required in subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction. In addition, a single dose of micafungin 100 mg was well tolerated in subjects with severe hepatic dysfunction and subjects with normal hepatic function, and there were no safety concerns throughout the study.

Conclusion

In summary, the findings of the present study indicate that although severe hepatic dysfunction affects micafungin PK, the magnitude of changes is not considered clinically meaningful and thus does not warrant dose adjustment in these individuals. This study also provides additional evidence showing that micafungin is well tolerated in subjects with hepatic dysfunction after a single dose of 100 mg.

Acknowledgments

This study was sponsored by Astellas. Medical writing and editorial support was provided by Neil M. Thomas, PhD, of Envision Scientific Solutions, funded by Astellas.

Conflict of interest

Nasrullah Undre is an employee of Astellas Pharma Europe Ltd., Chertsey, UK. Paul Stevenson was formerly an employee of Astellas Pharma GmbH Munich, Germany. Benjamin Pretorius was formerly an employee of Parexel International, South Africa.

References

- Astellas Pharma (2013) Mycamine: summary of product characteristics. http://www.ema.europa.eu/docs/en_GB/document_library/EPAR_-_Product_Information/human/000734/WC500031075.pdf. Accessed 19 March 2012

- Benjamin DK, Jr, Smith PB, Arrieta A, Castro L, Sánchez PJ, Kaufman D, Arnold LJ, Kovanda LL, Sawamoto T, Buell DN, Hope WW, Walsh TJ. Safety and pharmacokinetics of repeat-dose micafungin in young infants. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2010;8∝7(1):93–99. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2009.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wet NT, Bester AJ, Viljoen JJ, Filho F, Suleiman JM, Ticona E, Llanos EA, Fisco C, Lau W, Buell D. A randomized, double blind, comparative trial of micafungin (FK463) vs. fluconazole for the treatment of oesophageal candidiasis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21(7):899–907. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2005.02427.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowell JA, Stogniew M, Krause D, Damle B. Anidulafungin does not require dosage adjustment in subjects with varying degrees of hepatic or renal impairment. J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;47(4):461–470. doi: 10.1177/0091270006297227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fromtling RA. Micafungin sodium (FK-463) Drugs Today (Barc) 2002;38(4):245–257. doi: 10.1358/dot.2002.38.4.820091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groll AH, Mickiene D, Petraitis V, Petraitiene R, Ibrahim KH, Piscitelli SC, Bekersky I, Walsh TJ. Compartmental pharmacokinetics and tissue distribution of the antifungal echinocandin lipopeptide micafungin (FK463) in rabbits. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2001;45(12):3322–3327. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.12.3322-3327.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert MF, Blough DK, Townsend RW, Allison M, Buell D, Keirns J, Bekersky I. Concomitant tacrolimus and micafungin pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;45(9):1018–1024. doi: 10.1177/0091270005279274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert MF, Smith HE, Marbury TC, Swan SK, Smith WB, Townsend RW, Buell D, Keirns J, Bekersky I. Pharmacokinetics of micafungin in healthy volunteers, volunteers with moderate liver disease, and volunteers with renal dysfunction. J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;45(10):1145–1152. doi: 10.1177/0091270005279580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hebert MF, Townsend RW, Austin S, Balan G, Blough DK, Buell D, Keirns J, Bekersky I. Concomitant cyclosporine and micafungin pharmacokinetics in healthy volunteers. J Clin Pharmacol. 2005;45(8):954–960. doi: 10.1177/0091270005278601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarvis B, Figgitt DP, Scott LJ. Micafungin. Drugs. 2004;64(9):969–982. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200464090-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keirns J, Sawamoto T, Holum M, Buell D, Wisemandle W, Alak A. Steady-state pharmacokinetics of micafungin and voriconazole after separate and concomitant dosing in healthy adults. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2007;51(2):787–790. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00673-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuse ER, Chetchotisakd P, da Cunha CA, Ruhnke M, Barrios C, Raghunadharao D, Sekhon JS, Freire A, Ramasubramanian V, Demeyer I, Nucci M, Leelarasamee A, Jacobs F, Decruyenaere J, Pittet D, Ullmann AJ, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Lortholary O, Koblinger S, Diekmann-Berndt H, Cornely OA. Micafungin versus liposomal amphotericin B for candidaemia and invasive candidosis: a phase III randomised double-blind trial. Lancet. 2007;369(9572):1519–1527. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60605-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lass-Flörl C. The changing face of epidemiology of invasive fungal disease in Europe. Mycoses. 2009;52(3):197–205. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0507.2009.01691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merck Sharp & Dohme Limited (2011) Cancidas (caspofungin) summary of product characteristics. Merck Sharp & Dohme Limited. http://www.medicines.org.uk/emc/medicine/12843#PHARMACOKINETIC_PROPS. Accessed 19 March 2012

- Messer SA, Diekema DJ, Boyken L, Tendolkar S, Hollis RJ, Pfaller MA. Activities of micafungin against 315 invasive clinical isolates of fluconazole-resistant Candida spp. J Clin Microbiol. 2006;44(2):324–326. doi: 10.1128/JCM.44.2.324-326.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mistry GC, Migoya E, Deutsch PJ, Winchell G, Hesney M, Li S, Bi S, Dilzer S, Lasseter KC, Stone JA. Single- and multiple-dose administration of caspofungin in patients with hepatic insufficiency: implications for safety and dosing recommendations. J Clin Pharmacol. 2007;47(8):951–961. doi: 10.1177/0091270007303764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappas PG, Rotstein CM, Betts RF, Nucci M, Talwar D, De Waele JJ, Vazquez JA, Dupont BF, Horn DL, Ostrosky-Zeichner L, Reboli AC, Suh B, Digumarti R, Wu C, Kovanda LL, Arnold LJ, Buell DN. Micafungin versus caspofungin for treatment of candidemia and other forms of invasive candidiasis. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45(7):883–893. doi: 10.1086/520980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaller MA, Diekema DJ. Epidemiology of invasive candidiasis: a persistent public health problem. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2007;20(1):133–163. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00029-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfizer Inc. (2010) Eraxis™ (anidulafungin) prescribing information. Pfizer Inc., http://labeling.pfizer.com/ShowLabeling.aspx?id=566. Accessed 19 March 2012

- Undre N, Stevenson P, Baraldi E. Pharmacokinetics of micafungin in HIV positive patients with confirmed esophageal candidiasis. Eur J Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2012;37(1):31–38. doi: 10.1007/s13318-011-0063-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Undre N, Stevenson P, Kuse ER, demeyer I. Pharmacokinetics of micafungin in adult patients with invasive candidiasis and candidemia. Open J Med Microbiol. 2012;2(3):84–90. doi: 10.4236/ojmm.2012.23012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Undre NA, Stevenson P, Freire A, Arrieta A. Pharmacokinetics of micafungin in pediatric patients with invasive candidiasis and candidemia. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2012;31(6):630–632. doi: 10.1097/INF.0b013e31824ab9b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Burik JA, Ratanatharathorn V, Stepan DE, Miller CB, Lipton JH, Vesole DH, Bunin N, Wall DA, Hiemenz JW, Satoi Y, Lee JM, Walsh TJ. Micafungin versus fluconazole for prophylaxis against invasive fungal infections during neutropenia in patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39(10):1407–1416. doi: 10.1086/422312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van der Elst KC, Brüggemann RJ, Rodgers MG, Alffenaar JW. Plasma concentrations of caspofungin at two different dosage regimens in a patient with hepatic dysfunction. Transpl Infect Dis. 2012;14(4):440–443. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-3062.2011.00716.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiederhold NP, Lewis JS., 2nd The echinocandin micafungin: a review of the pharmacology, spectrum of activity, clinical efficacy and safety. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2007;8(8):1155–1166. doi: 10.1517/14656566.8.8.1155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamato Y, Kaneko H, Tanimoto K, Katashima M, Ishibashi K, Kawamura A, Terakawa M, Kagayama A. Simultaneous determination of antifungal drug, micafungin, and its two active metabolites in human plasma using high-performance liquid chromatography with fluorescence detection. Jpn J Chemother. 2002;50:68–73. [Google Scholar]