Abstract

Heart failure (HF) affects over 5 million Americans and is characterized by impairment of cellular cardiac contractile function resulting in reduced ejection fraction in patients. Electrical stimulation such as cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) and cardiac contractility modulation (CCM) have shown some success in treating patients with HF. Computer simulations have the potential to help improve such therapy (e.g. suggest optimal lead placement) as well as provide insight into the underlying mechanisms which could be beneficial. However, these myocyte models require a quantitatively accurate excitation-contraction coupling such that the electrical and contraction predictions are correct. While currently there are close to a hundred models describing the detailed electrophysiology of cardiac cells, the majority of cell models do not include the equations to reproduce contractile force or they have been added ad hoc. Here we present a systematic methodology to couple first generation contraction models into electrophysiological models via intracellular calcium and then compare the resulting model predictions to experimental data. This is done by using a post-extrasystolic pacing protocol, which captures essential dynamics of contractile forces. We found that modeling the dynamic intracellular calcium buffers is necessary in order to reproduce the experimental data. Furthermore, we demonstrate that in models the mechanism of the post-extrasystolic potentiation is highly dependent on the calcium released from the Sarcoplasmic Reticulum. Overall this study provides new insights into both specific and general determinants of cellular contractile force and provides a framework for incorporating contraction into electrophysiological models, both of which will be necessary to develop reliable simulations to optimize electrical therapies for HF.

Introduction

Heart failure (HF) affects over 5 million Americans and is characterized by impairment of cellular cardiac contractile function and reduced ejection fraction in patients[1]. Electrical stimulation such as cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) and cardiac contractility modulation (CCM) have shown success in treating patients with HF[2,3].

CRT is a current treatment for patients with congestive heart failure (CHF) for a wide QRS complex, where biventricular pacemakers are used to improve electrical synchrony and presumably ejection fraction[2,4]. However, the response to CRT varies greatly among patients. Improvements are quite variable with up to 30% of patients being non-responders to this treatment at all[2,5]. Nevertheless, the efficacy and optimization of CRT continues to being improved[6,7]. For example, it has been shown that extensive electrical remodeling is significantly associated with better survival rates after CRT[6]. Other measurements than electrical dyssynchrony have been investigated as identifications for CRT implantation estimation. It has been suggested that mechanical dyssynchrony is as well essential in prediction of CRT response[7].

An alternate electrical therapy for HF is cardiac contractility modulation (CCM) which delivers electric fields to the heart during its refractory period. Although its mechanism of action was initially thought to result from increased calcium flux from Sarcoplasmic Reticulum (SR)[3,8], recent studies suggest this is not the case, but that increased contractile function is the result of beta adregenergic stimulation[9]. Clinical studies have showed that CCM therapy improved quality of life, exercise capacity, New York Heart Association (NYHA) class, and ejection fraction (EF) during long-term follow up[10]. However, other clinical studies have reported contradictory evidence where CCM did not change effects on hospitalization or mortality[11], and it did not increase myocardial oxygen consumption[12].

It is clear then, that optimization of CRT and CCM therapies require an understanding of the effects of electric fields on myocyte dynamics especially for inotropicity as regulated by intracellular calcium. Computer simulations have the potential to improve these therapies through clarification of the underlying mechanisms[13]. For example, one challenge in CRT is to determine the optimal pacing locations; Miri et al. provided an optimization strategy to find the best pacing sites and timing delays in CRT based on biventricular-paced activation sequences and ECGs obtained from simulations using patient-specific anatomy and pathophysiology models[14]. Computer simulations can also be beneficial to help to predict the response of patients to certain therapies[15,16]. For instance, Niederer et al. have designed an electromechanical heart model based on clinical observations[17]. The model predicted that patients with dyssynchronous electrical activation but effective length-dependent tension regulation at the cellular scale are less likely to respond to CRT treatment than patients with attenuated or no length dependent of tension.

Such simulations of electrical therapy require a robust model of cellular excitation-contraction coupling that occurs in the cardiac myocyte such that the electrical and contraction predictions are both accurate. During the depolarization of an action potential, L-type Ca 2+ channels are activated and the influx of Ca 2+ current into the narrow dyadic space induces a large Ca 2+ release from the Junctional Sarcoplasmic Reticulum (JSR) through the Ryanodine Receptor (RyR). Intracellular Ca 2+ concentration is thus greatly increased immediately following the depolarization of the transmembrane action potential. Some of these Ca 2+ ions bind to affinity sites on Troponin C therefore enable myosin heads, which contain cross-bridges, to attach to actin. Myosin heads ‘walk’ on actin generating force, transforming chemical energy to mechanical energy resulting in cell contraction. Then during the repolarization of the action potential, Ca 2+ leaves the cytoplasmic compartment into either the Network Sarcoplasmic Reticulum (NSR) through the Ca-ATPase pump or out of the cell membrane though Na-Ca exchangers. The decreased intracellular Ca 2+ concentration causes Ca 2+ to detach from troponin C, inducing uncoupling of Myosin heads and actin, which ends the contraction process[18]. From this Ca 2+ handling process, we can see that Ca 2+ is deeply involved in the two highly non-linear systems, namely the electrical activation and tension generation and Ca 2+ binding with troponin C is the key component linking electrical signals to the activation of tension[18].

While there are close to a hundred cell models describing the detailed electrophysiology (EP) of cardiac cells, the majority of cell models do not include the equations to reproduce contractile force[19,20]. This is a considerable drawback. We suggest the most appropriate and challenging test for Electrical-contractile coupled (ECC) cell models derived from EP models is to reproduce the “postextrasystolic potentiation” (PESP) behavior of the heart[21]. PESP is an example of the changes in stimulation pattern on contractile strength. The effect can be demonstrated with the PESP pacing protocol[22]. First, a train of stimuli is delivered with a fixed basic cycle length called the priming period (PP). Second, an extrasystolic (ES) beat is delivered after the last priming stimulus by an interval called extrasystolic interval (ESI). Following the ES beat, a postextrasystolic (PES) beat is then delivered after another interval called the postextrasystolic interval (PESI). In normal hearts the strength of postrasystles is a function of both ESI and PESI. If ESI is fixed, postexatrasystolic strength increases as PESI is lengthened. If PESI is fixed, postextrasystolic strength increases as ESI is shortened. This effect includes mechanical restitution and pause dependence and it captures the important heart dynamics involving force generation and calcium cycling that occurs over multiple beats. Just like the electrical restitution protocol is a stringent test for electrical rate dependence, we believe that reproducing the PESP protocol is essential for an electromechanical cell model.

In this paper, we first present a systematical methodology to incorporate mechanical models into various existing EP models. We chose fourteen of the most recently developed EP models with multiple cellular compartments, advanced ionic currents and more realistic subcellular dynamics because they include the essential elements required to couple contraction models (e.g., SR dynamics and calcium buffers). We studied these models under the isometric condition by 1) evaluating how their calcium dynamics are affected by the inclusion of the contraction and 2) assessing how well these electromechanical models simulate contraction by comparing their PESP contractile response with experiments from Yue et al. and 3) analyzing the mechanism of PESP by finding the correlation between the calcium release from SR and the contractile strength. Finally we concluded with insights regarding the suitability of various models to reproduce electromechanical activities and the underlying mechanism of PESP, which may provide guidelines for future experiments.

Methods

In this section we introduced the contraction model that we implemented to EP models and the experiment we compared our simulations to, then we described our classification of EP models and corresponding strategy for contraction implementation, the numerical methods used to solve the models as well as the pacing protocols and data analysis. All terminology can be found in Table 1

Table 1. Terminology: definition of variables.

| Variable Type | Variable Name | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Pacing intervals | SSI (PI,PP) | Steady state interval (or priming interval/priming period): interval between steady state stimuli. It's 500ms in our simulations |

| ESI | Extrasystolic interval: interval between extrasystolic and the last steady state stimuli | |

| PESI | Postextrasystolic interval: interval between postextrasystolic and extrasystolic stimuli | |

| Measured quantity* | dP/dtmax(SS) | Maximum pressure rising rate of steady state beats |

| dP/dtmax(ES) | Maximum pressure rising rate of extrasystolic beats | |

| dP/dtmax(PES) | Maximum pressure rising rate of postextrasystolic beats | |

| [Ca2+]i | Intracellular calcium concentration | |

| Force-interval relations | MRCpes | Postextrasystolic mechanical restitution curve: normalized dP/dtmax of postextrasystoles plotted vs PESI |

| MRCes | Extrasystolic mechanical restitution curve: normalized dP/dtmax of extrasystoles plotted vs ESI | |

| PESPC | Postextrasystolic potentiation curve: normalized dP/dtmax of fully restituted postextrasystoles (CRmax,pes) plotted vs ESI | |

| Parameters for MRCpes ** | CRmax,pes | Maximum postextrasystolic contractile response: plateau value fpr MRCpes |

| Tmrc,pes | Time constant for MRCpes | |

| to,pes | PESI-axis intercept value | |

| Parameters for PESPC | A | Amplitude |

| B | Plateau value | |

| Tpespc | Time constant |

* Yue et al 1985 paper measured pressure changing rate. In our simulations we calculate tension changing rate and we replace P with F

** Paramters for MRCes are identical to MRCpes except replacing the subtitle 'pes' with 'es'

The Contraction Model and Experiment

We chose the Negroni_Lascano_1996 (NL96)[23]contraction model to represent the coupling of cross-bridge dynamics and intracellular Ca 2+ kinetics.

The muscle unit structure and cross-bridge dynamics are shown in Fig 1 in Negroni et al[23]. The muscle unit is composed of an inflexible thick filament (Myosin), a thin filament (actin) and an elastic paralleled element (titin). The cross-bridges are attached to the thick element on one end and can slide on the thin element on the other end. The total force is contributed by two parts: force generated from the elastic element (F p) and force generated by the cross-bridges (F b):

| (1) |

where K, A and L 0 are constants; L is the sarcomere length; TCa* and T* are two states associated with troponin C sites on the thin filament (defined below); h is the elongation of the muscle unit. For “isometric” contraction where the sarcomere length is fixed, F p is constant, and the total force is determined only by the force generated from the cross-bridges. Cross-bridge grabbing and sliding on the thin element will generate force F b which is proportional to the elongation (h) and the total number of attached cross-bridges. The number of attached cross-bridges is determined by the interaction with Ca 2+ and the relevant buffers, which is represented by a “four-state system” comprised of:1) sites on the thin element with free troponin C (T); 2) sites with Ca 2+ bound to troponin C (TCa); 3) sites with Ca 2+ bound to troponin C and attached cross-bridges (TCa*); and 4) sites with troponin C not bound to Ca 2+ but attached cross-bridges (T*). The system transitions among these four states via the binding and releasing of Ca 2+ and attaching and detaching of cross-bridges (See Fig 2 from Negroni et al [23]). The number of total cross-bridges is the sum of the two states that associated with cross-bridges ([TCa*]+[T*]). Equations represent the transitions among the four states in Fig 2 from Negroni et al [23] are:

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

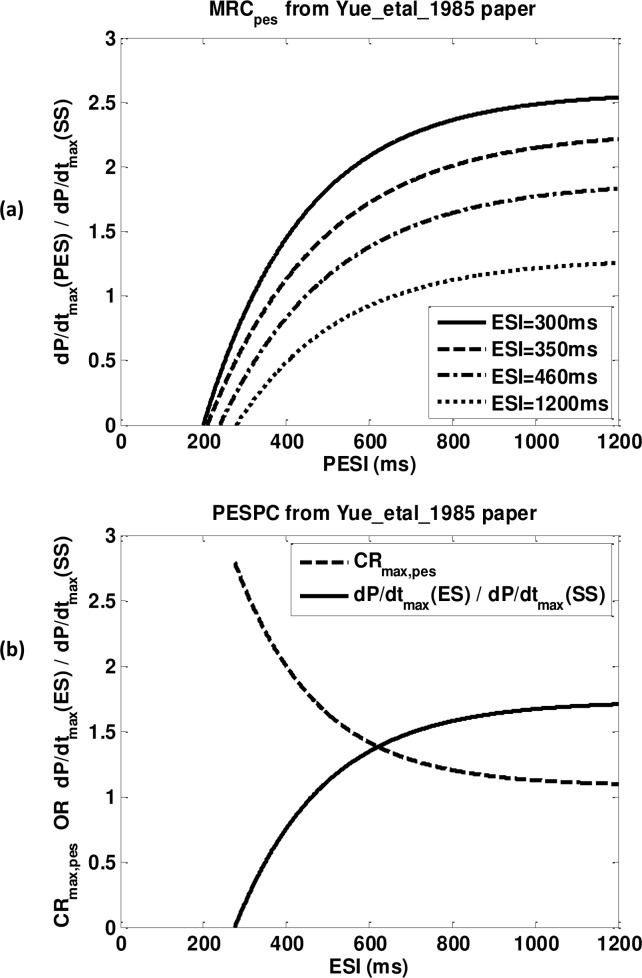

Fig 1. Contractile characteristic curves generated from equations in Yue experiments.

(a) Postextrasystolic mechanical restitution curves (MRC pes) using ESI equal to 300ms (solid line), 350ms (dash line), 460ms (dash-dot line) and 1200ms (dot line). (b) Postextrasystolic potnetiation curve (PESPC, dash line) and extrasystolic mechanical restitution curve (MRC es, solid line).

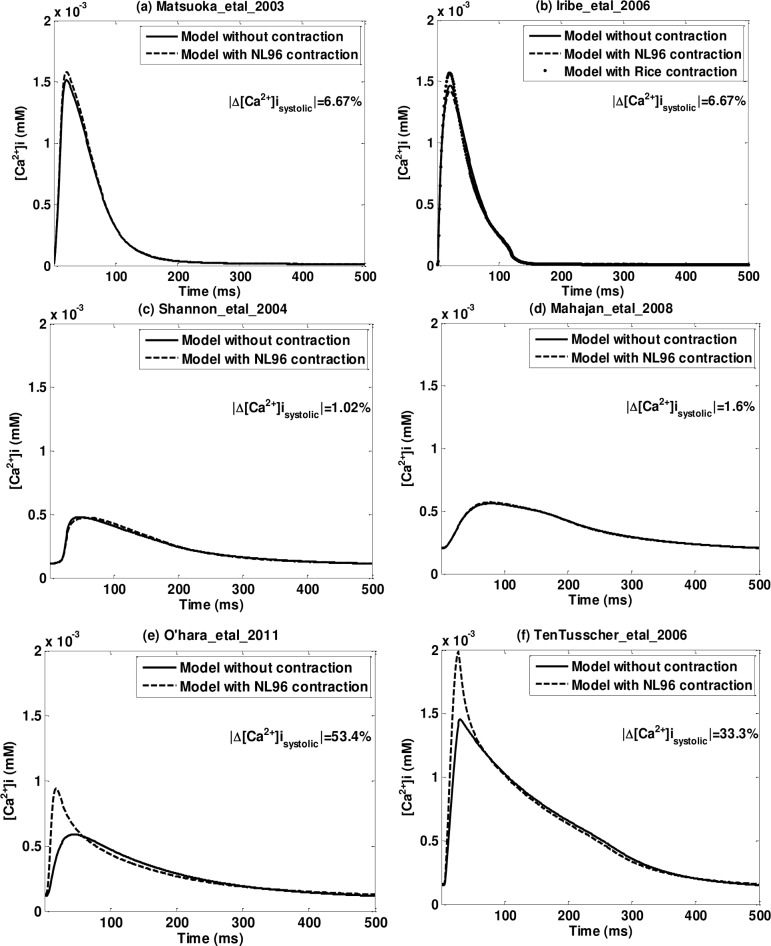

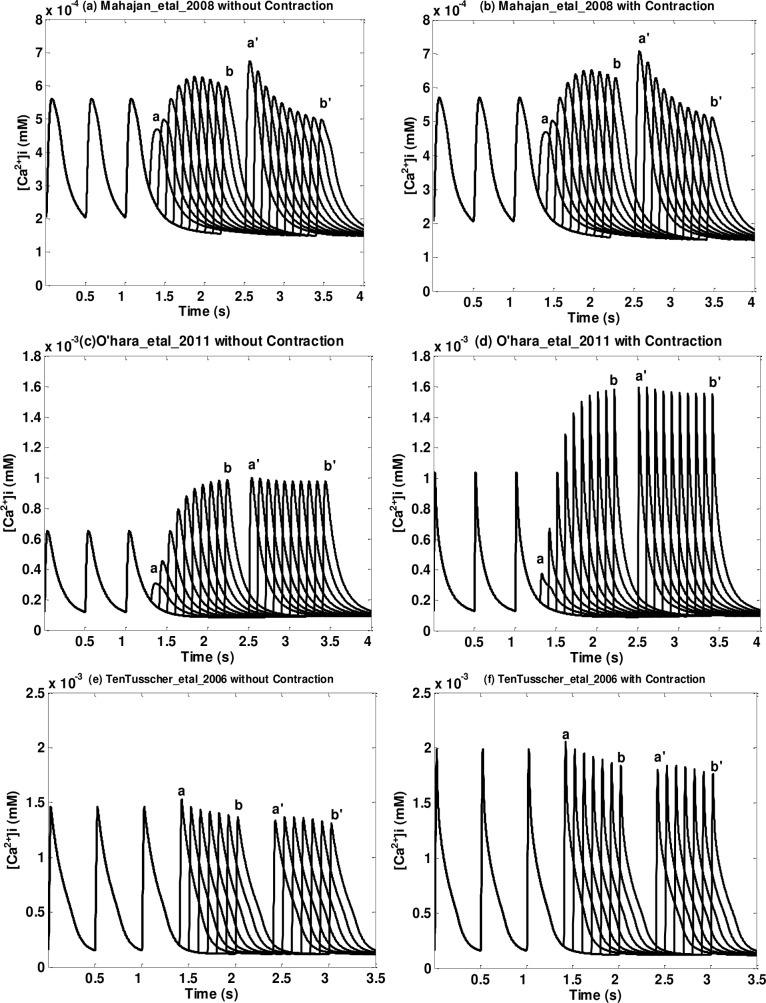

Fig 2. Priming [Ca 2+]i transient for six representative models.

(a) Matsuoka_etal_2003 (Type One: with contraction (NL96)); (b) Iribe_etal_2006 (Type One: with contraction (RWH99)); (c) Shannon_etal_2004 (Type Three: with full dynamic calcium buffers); (d) Mahajan_etal_2008 (Type Three: with dynamic calcium troponin buffer); (e) O’hara_etal_2011 (Type Four: with instantaneous calcium troponin buffer); (f) TenTusscher_etal_2006 (Type Five: with no calcium troponin buffer). Solid lines are models without contraction; dash lines are models with NL96 contraction. All figures have the same ranges in x and y axis. The insets show the relative difference in systolic [Ca 2+]i between models with contractions and without contractions.

These are reaction equations among the states of free troponin (T), troponin attached with cross-bridges (T*), troponin bound with calcium (TCa), and troponin bound with calcium attached with cross-bridges (TCa*); all with units of mM/ms. [TCa]eff is the effective [TCa] where cross-bridge attachment can occur and it’s dependent on the sarcomere length (see Eq 10 in [23]). X = L − h, which is the inextensible length in the muscle unit. Y1 ∼ Y4, Z1 ∼ Z3 and Yd are rate constants. The NL96 model includes feedback from force on Ca 2+; therefore it is, in general, a “strongly coupled” contraction model, but under isometric condition it is “weakly coupled” since dX / dt = 0 [24].

There are two reasons why we chose the NL96 model. First, it shares common elements with the EP models; this greatly simplifies the implementation procedure. For example, the four states in the Ca 2+ kinetics are closely related to intracellular Ca 2+ concentration and Troponin concentration, both of which are common elements in advanced EP models. Second, even though NL96 model is a simplified model of the average effect of the interaction between myosin and actin, it can effectively reproduce basic physiological findings, such as time course of isometric force, intracellular Ca 2+ transient and force-length- Ca 2+ relation. Third, our method to incorporate NL96 can be easily applied to other contraction models as long as they use ODEs to describe the Ca 2+ troponin states, like [25][26][27].

To evaluate the ability of these fourteen “coupled” electromechanical models to reproduce experimental findings, we compared the results of the simulations with the isovolumetric canine ventricular experiments from Yue et al.[22]. We chose Yue et al. because their paper includes not only a comprehensive experimental exploration of the relation between the contractile strength and pacing intervals but also a concise mathematical framework that allows quantitative comparisons of model predictions.

We applied the same PESP pacing protocol employed by Yue et al. [22], which was introduced in the Introduction section. By fixing ESI and varying PESI, Yue et al. [22] measured the rate of pressure change of the PES beat as a function of PESI; then by changing ESI to another value and repeatedly varying PESI, a family of curves can be constructed showing the effect of both ESI and PESI on pressure change (see Fig 2 from Yue et al [22]). In contrast to electrical restitution in which action potential duration is recorded for a single extrasystolic beat, the purpose of the PESP protocol is to study the contractile strength as a function of a single extrasystolic followed by a compensatory pause. The idea is to capture the full cycle Ca 2+ handling, specifically the release of calcium from the SR as a function of timing and the dynamics of the restoration of releasable SR Ca 2+ during (and following) action potential repolarization. The basic theory lies in the fact that Ca 2+ release from the SR is determined by two factors: the recovery of Ryanodine Receptor’s (RyR’s) which is a function of interbeat interval; and the amount of Ca 2+ in the SR. When ESI>PP, RyRs are more recovered from the last priming beat, resulting in a bigger Ca 2+ release from SR for the ES beat. Consequently, the Ca 2+ content in SR will be smaller compared to the priming period, and may lead to a smaller or larger Ca 2+ release (compared to PP) for the next PES beat depending on the PESI.

In Yue’s experiments, they measured the maximum rate of pressure change in fourteen isolated perfused left canine ventricles under isovolumetric conditions. In the NL96 contraction model, force (normalized to muscle cross section area) is the variable to quantify the contractile strength; therefore to correlate with Yue’s experiment results, we assumed a linear relationship between force generated from single cell and ventricular pressure[28], and thus we compare the normalized maximum rate of force change in our simulations with the normalized maximum rate of pressure change in Yue’s paper.

Ventricular models and electrophysiological contraction implementation

We studied fourteen ventricular cell models, which include four species: guinea pig (n = 4)[29][30][31][32], rabbit (n = 2)[33][34], dog (n = 2)[35][36] and human (n = 6)[37][38][39][40][41][42]. We classify the models into five categories based on the type of their calcium buffers and designed corresponding strategies to implement NL96. The complexity of the implementation of contraction into these five types of models is listed in ascending order. The flowchart in the S1 File illustrates steps of the implementation. We provide the essential equations, initial conditions and choice of parameters below. More details can be found in the S1 File. Table 2 lists general information about all models including classification, species, buffer information, number of variables, stimulus current amplitudes and durations; rate constants for Ca 2+ troponin buffers can be found in Table 3.

Table 2. General information of 14 electrophysiological models including classification of models (model type, model name, species, type of intracellular Ca 2+ buffers) and model properties (number of variables in the original model, stimulus current amplitude and duration).

| Model Type | Model Name | Species | CaTRPN buffer | Other Ca buffers | Number of variables | stimulus current(A/F) | stimulus duration(ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type 1 | Matsuoka_etal_2003 | guinea pig | NL96 | none | 37 | -8 | 1 |

| Iribie_etal_2006 | guinea pig | RWH99 | dynamic | 23 | -4 | 2 | |

| Type 2 | Shannon_etal_2004 | rabbit | dynamic | dynamic | 39 | -15 | 4 |

| Grandi_etal_2010 | human | dynamic | dynamic | 39 | -9.5 | 4 | |

| Type 3 | Mahajan_etal_2008 | rabbit | dynamic | instantaneous | 26 | -30 | 2 |

| Iyer_etal_2004 | human | dynamic | instantaneous | 67 | -25 | 2 | |

| Type 4 | Hund_etal_2004 | dog | instantaneous | instantaneous | 29 | -30 | 2 |

| Faber_etal_2000 | guinea pig | instantaneous | instantaneous | 25 | -25.5 | 2 | |

| Livshitz_etal_2007 | guinea pig | instantaneous | instantaneous | 18 | -15 | 2 | |

| Ohara_etal_2011 | human | instantaneous | instantaneous | 41 | -80 | 0.5 | |

| Priebe_etal_1998 | human | instantaneous | instantaneous | 22 | -30 | 2 | |

| Type 5 | Fox_etal_2002 | dog | none | instantaneous | 13 | -80 | 1 |

| TenTusscher_etal_2006 | human | none | instantaneous | 19 | -51 | 1 | |

| Fink_etal_2008 | human | none | instantaneous | 27 | -24 | 2 |

Table 3. General information of 14 electrophysiological models including parameters of CaTRPN (K d, K on, K off), approximate time to reach quiescent states, beat number to reach priming steady states and ESI,PESI ranges.

| Model Type | Model Name | K d (mM) | K on (mM-1ms-1) | K off (ms-1) | Quiescent time | Prime beat No | ESI(ms) | PESI(ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type 1 | Matsuoka_etal_2003 | 7.69E-04 | 3.90E+01 | 3.00E-02 | 20min | 500 | 250–1200 | 100–1200 |

| Iribie_etal_2006 | function of F | 8.00E+01 | 3.00E-01 | 10min | 500 | 200–1200 | 100–1200 | |

| Type 2 | Shannon_etal_2004 | 6.00E-04 | 3.27E+01 | 1.96E-02 | 20min | 1500 | 200–1200 | 100–2000 |

| Grandi_etal_2010 | 6.00E-04 | 3.27E+01 | 1.96E-02 | 20min | 500 | 300–1200 | 200–1200 | |

| Type 3 | Mahajan_etal_2008 | 6.00E-04 | 3.27E+01 | 1.96E-02 | 10min | 1500 | 300–1200 | 200–1200 |

| Iyer_etal_2004 | 1.00E-03 | 4.00E+01 | 4.00E-02 | 40min | 15000 | 250–1500 | 200–1500 | |

| Type 4 | Hund_etal_2004 | 5.00E-04 | 3.58E+01 | 1.79E-02 | 80min | 6000~10500 | 250–1200 | 150–1200 |

| Faber_etal_2000 | 5.00E-04 | 3.58E+01 | 1.79E-02 | 20min | 1500 | 200–1500 | 350–1500 | |

| Livshitz_etal_2007 | 5.00E-04 | 3.58E+01 | 1.79E-02 | 20min | 1500 | 200–1200 | 200–1200 | |

| Ohara_etal_2011 | 5.00E-04 | 3.58E+01 | 1.79E-02 | 20min | 1000 | 300–1200 | 200–1200 | |

| Priebe_etal_1998 | 5.00E-04 | 3.58E+01 | 1.79E-02 | 20min | 1500 | 400–2000 | 400–2000 | |

| Type 5 | Fox_etal_2002 | 6.00E-04 | 3.27E+01 | 1.96E-02 | 20min | 1500 | 200–2000 | 200–2000 |

| TenTusscher_etal_2006 | 1.00E-03 | 2.53E+01 | 2.50E-02 | 20min | 1500 | 400–1000 | 450–1000 | |

| Fink_etal_2008 | 1.00E-03 | 2.53E+01 | 2.50E-02 | 40min | 1500 | 350–1200 | 350–1200 |

Type One: models with contraction

Two of the fourteen models have contraction in their original versions: Iribe_etal_2006[30] and Matsuoka_etal_2003[29].

Matsuoka_etal_2003 already has NL96 contraction in the original version. However, to investigate how much influence the mechanics has on this model, we remove the NL96 model and make Ca 2+ troponin (CaTRPN) a single-state-variable dynamic buffer (original model is a four-state variable dynamic buffer):

| (6) |

[Ca 2+]i is the intracellular Ca 2+ concentration; B max,troponin is the total Troponin concentration; K on and K off are rate constants for the chemical reaction:

| (7) |

We set K on and K off to the values of Y1 and Z1 and B max,troponin to the value in the original model. We call this new model Matuoska_etal_2003 without Contraction.

Iribe_etal_2006 includes the contraction model of Rice et al. (RWH99) in the original version [25]. For RWH99, CaTRPN is expressed by a single-state dynamic equation like Eq 6 but with a dynamic rate constant K off that depends on force, hence it is strongly coupled even for isometric contractions. Also the RWH99 model has six tropomyosin/cross-bridge states with rate constants that are functions of the Ca 2+ troponin buffer. To simulate this model without the contraction part, we eliminated the six tropomyosin/cross-bridge states and set K off for CaTRPN to a constant value by fixing the force in K off expression to half of its maximum value. We then compare simulations of the original model and the version without contraction as well as one with NL96 contraction model (implemented as described in the next “Type Two” section).

Type Two: models with full dynamic buffers

Two of the models incorporate ordinary differential equations (ODEs) for all the buffers: Shannon_etal_2004[33] and Grandi_etal_2010[37]. The equations for the original Ca 2+ troponin buffers in these models are the same as Eq 6. For models of Type Two we add the four-state NL96 model using Eqs 2–5 above; this is done by splitting the dynamical Ca 2+ troponin buffer in the original model into two states: with (TCa*) or without (TCa) cross-bridges (Eqs 3 and 4):

| (8) |

and adding the other two states T and T* (Eqs 2 and 5). There are multiple K on and K off in Eqs 2–4: Yd, Y1∼Y4, Z1∼Z3. They are kept the same as original NL96 paper[23] except for Y 1 and Z 1, which are chosen to match the values of K on and K off in Eq 6 from the original model (see Table 3). This is to preserve the dynamics of CaTRPN as similar as possible to the original model.

Type Three: models with dynamic Ca 2+ troponin buffers

Two of the models use ODEs for CaTRPN but instantaneous forms for all the other buffers: Mahajan_etal_2008[34] and Iyer_etal_2004[38].

For this type of models we follow the same step regarding the dynamic Ca 2+ troponin buffer in Type Two above and keep all the other buffers instantaneous. The only difference between Type Three and Type Two is that there are instantaneous buffer factors in Type Three models (see Eqs 9 and 10 below) but not in Type two.

Type Four: models with instantaneous Ca 2+ troponin buffers

Five of the models have all instantaneous Ca 2+ buffers: Hund_etal_2004[35]; Faber_etal_2000[31]; Livshitz_etal_2007[32]; Ohara_etal_2011[39] and Priebe_etal_1998[40]. The buffering of Ca 2+ by Troponin is represented using the following equations:

| (9) |

| (10) |

represents the total intracellular Ca 2+ flux (see Page 18 in the supplement in reference [39] for detailed fomula); β is the instantaneous buffer factor; index j represents each type of intracellular Ca 2+ buffer; B max, j and K d,j are the total concentration and the affinity constant for buffer j. For this type of model we first change the instantaneous intracellular Ca 2+ troponin buffer into a dynamic buffer by eliminating the CaTRPN term from the instantaneous buffer factor β and by adding a dynamic CaTRPN flux into the [Ca 2+]i equation:

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

The way to choose K on and K off here is not unique as long as in the original model. We choose and , where s indicates the values from the Shannon_etal_2004 model and . We use the values from Shannon_etal_2004 as the standard values here because they have been widely used by to simulate dynamic CaTRPN buffers. After changing the instantaneous CaTRPN into a dynamical buffer, we follow the same procedure as for Type Three models.

Type Five: models without Ca 2+ troponin buffers

Three of the models do not have Ca 2+ troponin buffers, but they do have other intracellular Ca 2+ buffers: Fox_etal_2002[36]; TenTusscher_etal_2006[41] and Fink_etal_2008[42].

For this type of models, we first add instantaneous Ca 2+ troponin buffers into the models. If the model has one general Ca 2+ buffer (referred as General) representing the average effect of all intracellular Ca 2+ buffers (e.g. TenTusscher_etal_2006 and Fink_etal_2008), we split the general buffer into two parts: CaTRPN and “Other”. We keep K d,TRPN and K d,Other to be the same as K d,General in the original model so that the Ca 2+ affinity of the instantaneous buffer will be retained. [Troponin]total was set to be 0.07mM, which is a standard value in most models. [Other]total = [General]total − [Troponin]total so that the concentration of the total intracellular Ca 2+ buffer is the same as in the original model. If the model has other Ca 2+ buffers (such as CMDN) but no CaTRPN (e.g. Fox_etal_2002), we keep the other buffers unchanged and add a CaTRPN buffer. For the new CaTRPN buffer we also set [Troponin]total = 0.07mM and K d,CaTRPN = 0.6μM which are both common values in many models. After adding an instantaneous CaTRPN to the model, we follow the steps for Type Four to implement NL96.

Numerical integration

Except for one model (Iyer_etal_2004), all the code for the original single cell models were downloaded from www.cellml.org in CELLML format. Then they were translated into.mat files (MATLAB files) using a PYCML program.[43][44] Simulations were run in MATLAB and integrated using the forward Euler integration method with time steps of dt = 0.001ms. The Iyer_etal_2004 model consists of 67 variables and requires a dt integration step as low as 1×10−5 ms to converge[38] using forward Euler, thus becoming impractically slow to simulate in MATLAB. Therefore as in [45] the Iyer_etal_2004 model was written in FORTRAN using a semi-implicit integration method that allows a much larger (while still convergent) integration time step of dt = 0.005ms.

Pacing protocol and initial conditions

Our pacing protocol is composed of three steps and similar to the pacing protocol from Yue et al [22] except that we chose to use a priming period of 500ms. The stimulus currents and durations for the different models were selected to ensure excitation and the values are provided in Table 2. All simulations were run for isometric contraction of a single cell, where the half sarcomere length is fixed to be 1.05μm.

Step one: Quiescent

In this step, EP models without contractions were run with no stimulation current until quiescent steady states were reached (i.e., no state variable changed by more than 0.01%). Initial values for state variables in each model were directly loaded from CellML code. The time for each model to reach the quiescent state is listed in Table 3, and it ranges from 10min of real time (as in the Mahajan_etal_2008 model) to up to 100min (as in the Hund_etal_2004 model). Note that these are real times and not run times. Steady state quiescent values for voltage, intracellular and JSR (or SR) Ca 2+ concentrations vary considerably among models as shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Quiescent state variables: membrane voltage, intracellular calcium condensation and JSR (or SR) calcium condensation.

| Model Type | Model name | whether original* | Vm (mV) | [Ca2+]i (mM) | [Ca2+]JSR (mM) | [Ca2+]SR(mM) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type 1 | Matsuoka_etal_2003 | No | -85.9 | 2.92E-06 | 4.76E+00 | 5.50E+00 |

| Iribie_etal_2006 | No | -94.3 | 5.50E-06 | NA | 6.82E-03 | |

| Type 2 | Shannon_etal_2004 | Yes | -85.4 | 7.06E-05 | NA | 4.58E-01 |

| Grandi_etal_2010 | Yes | -81.0 | 7.08E-05 | NA | 4.60E-01 | |

| Type 3 | Mahajan_etal_2008 | Yes | -86.4 | 5.31E-05 | 3.68E-02 | 7.36E-02 |

| Iyer_etal_2004 | Yes | -91.6 | 1.40E-05 | 3.92E-02 | 7.84E-02 | |

| Type 4 | Hund_etal_2004 | Yes | -86.9 | 8.34E-05 | 1.27E+00 | 2.54E+00 |

| Faber_etal_2000 | Yes | -85.3 | 7.19E-05 | 1.09E+00 | 2.18E+00 | |

| Livshitz_etal_2007 | Yes | -90.0 | 8.00E-05 | 7.20E+00 | 8.40E+00 | |

| Ohara_etal_2011 | Yes | -88.3 | 5.58E-05 | 9.82E-01 | 1.96E+00 | |

| Priebe_etal_1998 | Yes | -91.6 | 9.26E-05 | 1.58E+00 | 3.17E+00 | |

| Type 5 | Fox_etal_2002 | Yes | -94.3 | 5.02E-05 | NA | 1.11E+00 |

| TenTusscher_etal_2006 | Yes | -87.5 | 2.58E-05 | NA | 1.87E-01 | |

| Fink_etal_2008 | Yes | -86.8 | 9.05E-05 | NA | 2.05E+00 |

* If the original model does not have contraction, we run the original model to get quiescent state. If the original model has contraction, we take out the contraction part and run that to quiescent state.

Step Two: Priming Cycle

During the priming pacing cycle, all models (with and without contractions) were paced with priming period T = 500ms starting from the quiescent states at the end of Step one, until a new “priming” steady state was achieved. The beat number required to reach this priming steady state for each model is listed in Table 2. For models incorporating NL96 contraction, state variables for the four states of Ca 2+ troponin buffer were calculated by solving Eqs 2–5 for steady state using the quiescent value of [Ca 2+]i. The total Ca 2+ troponin buffer ([TCa]+[TCa*]) calculated using this method was verified to be similar to the quiescent value in the original EP model if the original model had a Ca 2+ troponin buffer. We used this method to ensure that the initial conditions for the original models and the corresponding contraction models were as close as possible.

Step Three: Postextrasystolic pacing protocol

For all models, an extrasystolic (ES) and a postextrasystolic (PES) beat were delivered in sequence after the last priming beat as described in the Contraction Model and Experiment section. We held ESI at a constant value and varied PESI to record the transients of transmembrane potential, [Ca 2+]i, CaTRPN and generated force; we then changed ESI to a different value and repeated the process using the priming steady state as initial conditions. The shortest PESI is the refractory period of the ES beat so it is just long enough that the PES beat is separated from the ES beat. The longest PESI (ESI) value was chosen as 1200ms, 1500ms or 2000ms, depending on the time it took for the Postextrasystolic MRC pes (MRC es) to converge to a plateau level, as some models took longer than others to reach it.

Data Analysis

All curves were fitted using MATLAB’s built-in function “fit” whose default curve fit algorithm is the Trust-Region method. The value of r2 was given for each fit and 95% confidence bounds were provided for each fitted coefficient. Our analysis is divided into two parts: Ca 2+ dynamics and Contraction. To analyze Ca 2+ dynamics we compare the Ca 2+ transients for the priming beats and during postextrasystolic potentiation between the original models and models with contraction. To analyze Contraction we generate four characteristic contraction curves and fit two of them into monoexponential functions.

Ca2+ Dynamics

Priming Ca 2+: For each model, we plotted the intracellular Ca 2+ of the last priming beat, i.e. priming steady state, for both the original model and the one with contraction implemented in the same plot. We quantified the Ca 2+ transient by calculating the following: 1) minimum (diastolic) [Ca 2+]i; 2) maximum (systolic) [Ca 2+]i; 3) the duration for which [Ca 2+]i was above its half amplitude level, i.e. [Ca 2+]i ≥ [Ca 2+]diastolic + ([Ca 2+]systolic − [Ca 2+]diastolic) / 2; 4) the time at which [Ca 2+]i reached its maximum systolic value (t peak); and 5) the amplitude of the total Ca 2+ charge delivered to the cytoplasmic compartment during one beat (Q) that was calculated by integrating the area underneath the [Ca 2+]i − [Ca 2+]diastolic transient. We quantified the differences of the parameters between original models and models with contractions by the relative difference, defined as

| (14) |

Postextrasystolic Potentiation in [Ca2+]i: For each model, we plotted the intracellular Ca 2+ transient for the last 3 priming beats, along with multiple ES/PES beat pairs overlaid on the same graph for each model (without contraction on the left and with contraction of the right).

Contraction

Following the data fitting and analysis from Yue paper[22] with modification, we generate four characteristic curves for each model after the implementation of contraction: Postextrasystolic Mechanical Restitution Curve (MRC pes ), Postextrasystolic Potentiation Curve (PESPC), Minimum-value Axis Intercept Curve (t o,pes plotted vs ESI) and Time Constant Curve (T mrc,pes plotted vs ESI).

Postextrasystolic (PES) Mechanical Restitution Curves (MRC pes ) are a family of curves of maximum rate of change of force of postextrasystolic beats normalized to the last priming beat plotted vs PESI. For a fixed ESI, MRC pes increases monoexponentially to a plateau level (the fully restituted value) as PESI increases. The equation for this MRC pes is:

| (15) |

where F denotes the force generated from NL96 model; PES denotes that it is the postextrasystolic beat; SS denotes the steady state during the priming period; CR max,pes is the plateau amplitude, termed as Maximum Postextrasystolic Contractile Response; C 0 is the minimum value of , in Yue et al.[22] C 0 = 0; t o,pes is the minimum-value axis intercept where MRC pes intercepts the minimum value line ; and T mrc,pes is the time constant for MRC pes.. Fig 1(A) shows one set of MRC pes generated using equations and parameters in Yue et al.[22].

Extrasystolic (PES) Mechanical Restitution Curves (MRC es) presents the maximum rates of change of force of extrasystolic beats normalized to the last priming beat (dF / dt max (ES) / dF / dt max(SS)) as a function of ESI. Since it is a subset of MRC pes with ESI equal to the priming cycle length, we do not present them separately.

Postextrasystolic Potentiation Curve (PESPC) is the maximum postextrasystolic contractile response (CR max,pes) plotted vs ESI. CR max,pes is the plateau amplitude of the above MRC pes for a fixed ESI and this amplitude decreases to a plateau value as ESI increases. Fig 1(B) shows the PESPC and the simultaneously determined MRC es , both generated from the equations in Yue et al.[22]. The equation for PESPC fitting is:

| (16) |

where B is the plateau level; A is the amplitude; t o,es is the ESI-axis intercept for the simultaneously determined Extrasystolic Mechanical Restitution Curve; T pespc is the time constant for PESPC.

Results

Our Results section is divided into three parts: Calcium Results, Contraction Results, and the Underlying Mechanism for PESP. In the Calcium Results section we first compared the Priming Ca 2+ transients between original EP models and the corresponding models with the NL96 contraction model to investigate the influence of including contraction on EP models. Then we studied the Postextrasystolic Potentiation behavior in Ca 2+ before and after the implementation of contraction. In the Contraction Results section we compared the four characteristic contractile curves with the Yue et al. experimental results. In the Underlying Mechanism for PESP section we analyzed the mechanism of PESP by finding the correlation between the calcium release from SR and the contractile strength.

Ca2+ Results

Priming [Ca 2+]i properties are undisturbed after the implementation of contraction for models with dynamic buffers

We present the priming [Ca 2+]i data in Fig 2, Tables 5, 6, 7 and the S2 File. Fig 2(A)–2(F) illustrates [Ca 2+]i transients for the last priming beat for six representative models with (dashed lines) and without (solid lines) contraction. They are chosen to include five of the different EP types: (a) Matsuoka_etal_2003 (Type One: with contraction(NL96)); (b) Iribe_etal_2006 (Type One: with contraction(RWH99)); (c) Shannon_etal_2004 (Type Two: full dynamic Ca 2+ buffer); (d) Mahajan_etal_2008 (Type Three: dynamic Ca 2+ troponin buffer); (e) Ohara_etal_2004 (Type Four: instantaneous Ca 2+ troponin buffer); (f) TenTusscher_etal_2006 (Type Five: no Ca 2+ troponin buffer). The corresponding plots for all the fourteen models are provided in S2 File.The five quantities computed to quantify the priming [Ca 2+]i transient for all EP models without (with) contraction are provided in in Table 5 (Table 6) and the relative differences between before and after contraction are shown in Table 7, where double dagger symbols (‡) indicate the differences larger than 0.5(50%); single dagger symbols (†) indicate differences larger than 0.1 (10%) but less than 0.5 (50%).

Table 5. Data for steady priming beat: EP models without contraction.

| Model Type | Model Name | [Ca2+]i_diastolic(mM) | [Ca2+]i_systolic(mM) | t1/2(ms) | tpeak(ms) | Q (mM*ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type 1 | Matsuoka_etal_2003 | 1.46E-05 | 1.50E-03 | 5.69E+01 | 2.02E+01 | 9.80E-02 |

| Iribie_etal_2006 | 1.03E-05 | 1.50E-03 | 5.25E+01 | 2.08E+01 | 8.40E-02 | |

| Type 2 | Shannon_etal_2004 | 1.13E-04 | 4.80E-04 | 1.41E+02 | 4.60E+01 | 5.90E-02 |

| Grandi_etal_2010 | 1.11E-04 | 3.82E-04 | 1.42E+02 | 5.49E+01 | 4.49E-02 | |

| Type 3 | Mahajan_etal_2008 | 2.04E-04 | 5.61E-04 | 1.94E+02 | 7.90E+01 | 7.57E-02 |

| Iyer_etal_2004 | 2.33E-04 | 9.90E-04 | 2.23E+02 | 7.80E+01 | 1.80E-01 | |

| Type 4 | Hund_etal_2004 | 1.86E-04 | 7.37E-04 | 1.64E+02 | 4.27E+01 | 1.02E-01 |

| Faber_etal_2000 | 2.45E-04 | 2.00E-03 | 9.75E+01 | 1.47E+01 | 2.04E-01 | |

| Livshitz_etal_2007 | 1.73E-04 | 1.40E-03 | 1.20E+02 | 2.20E+01 | 1.61E-01 | |

| Ohara_etal_2011 | 1.18E-04 | 6.52E-04 | 1.37E+02 | 4.31E+01 | 8.74E-02 | |

| Priebe_etal_1998 | 4.31E-04 | 9.73E-04 | 1.75E+02 | 1.52E+01 | 1.10E-01 | |

| Type 5 | Fox_etal_2002 | 3.80E-05 | 1.62E-03 | 8.22E+01 | 1.75E+01 | 1.52E-01 |

| TenTusscher_etal_2006 | 1.51E-04 | 1.50E-03 | 1.38E+02 | 2.93E+01 | 2.10E-01 | |

| Fink_etal_2008 | 1.42E-04 | 1.50E-03 | 1.02E+02 | 3.43E+01 | 1.72E-01 |

Table 6. Data for steady priming beat: models with NL96 contraction.

| Model Type | Model Name | [Ca2+]i_diastolic(mM) | [Ca2+]i_systolic(mM) | t1/2 (ms) | tpeak (ms) | Q (mM*ms) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type 1 | Matsuoka_etal_2003 | 1.49E-05 | 1.60E-03 | 5.65E+01 | 2.01E+01 | 1.02E-01 |

| Iribie_etal_2006 | 1.04E-05 | 1.40E-03 | 5.26E+01 | 2.06E+01 | 8.19E-02 | |

| Type 2 | Shannon_etal_2004 | 1.12E-04 | 4.75E-04 | 1.46E+02 | 5.80E+01 | 5.99E-02 |

| Grandi_etal_2010 | 1.14E-04 | 3.87E-04 | 1.35E+02 | 5.48E+01 | 4.38E-02 | |

| Type 3 | Mahajan_etal_2008 | 2.06E-04 | 5.70E-04 | 1.89E+02 | 7.80E+01 | 7.49E-02 |

| Iyer_etal_2004 | 2.41E-04 | 1.00E-03 | 2.16E+02 | 7.60E+01 | 1.83E-01 | |

| Type 4 | Hund_etal_2004 | 1.95E-04 | 1.20E-03 | 7.05E+01 | 1.18E+01 | 1.06E-01 |

| Faber_etal_2000 | 2.27E-04 | 4.80E-03 | 6.90E+00 | 3.79E+00 | 1.80E-01 | |

| Livshitz_etal_2007 | 1.86E-04 | 2.30E-03 | 2.99E+01 | 1.60E+01 | 1.19E-01 | |

| Ohara_etal_2011 | 1.29E-04 | 1.00E-03 | 5.81E+01 | 1.66E+01 | 9.00E-02 | |

| Priebe_etal_1998 | 4.23E-04 | 1.60E-03 | 1.93E+01 | 1.01E+01 | 1.11E-01 | |

| Type 5 | Fox_etal_2002 | 1.16E-04 | 2.79E-04 | 1.86E+02 | 1.38E+01 | 3.35E-02 |

| TenTusscher_etal_2006 | 1.59E-04 | 2.00E-03 | 7.47E+01 | 2.59E+01 | 2.15E-01 | |

| Fink_etal_2008 | 1.49E-04 | 2.00E-03 | 5.99E+01 | 3.14E+01 | 1.75E-01 |

Table 7. Data for steady priming beat: relative differences between EP models and models with NL96 contractions.

| Model Type | Model Name | Δ[Ca2+]i_diastolic | Δ[Ca2+]i_systolic | Δt1/2 | Δtpeak | ΔQ |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type 1 | Matsuoka_etal_2003 | 1.80E-02 | 6.67E-02 | -7.33E-03 | -7.52E-03 | 3.78E-02 |

| Iribie_etal_2006 | 1.06E-02 | -6.67E-02 | 1.54E-03 | -9.41E-03 | -2.55E-02 | |

| Type 2 | Shannon_etal_2004 | -5.31E-03 | -1.02E-02 | 3.55E-02 | 2.61E-01‡ | 1.53E-02 |

| Grandi_etal_2010 | 2.23E-02 | 1.23E-02 | -4.68E-02 | -2.31E-03 | -2.45E-02 | |

| Type 3 | Mahajan_etal_2008 | 1.03E-02 | 1.60E-02 | -2.58E-02 | -1.27E-02 | -9.66E-03 |

| Iyer_etal_2004 | 3.31E-02 | 1.03E-02 | -3.15E-02 | -2.56E-02 | 1.72E-02 | |

| Type 4 | Hund_etal_2004 | 4.82E-02 | 6.28E-01‡ | -5.71E-01‡ | -7.25E-01‡ | 3.53E-02 |

| Faber_etal_2000 | -7.55E-02 | 1.60E+00‡ | -9.29E-01‡ | -7.43E-01‡ | -1.21E-01† | |

| Livshitz_etal_2007 | 7.47E-02 | 6.43E-01‡ | -7.51E-01‡ | -2.73E-01† | -2.61E-01† | |

| Ohara_etal_2011 | 9.24E-02 | 5.34E-01‡ | -5.75E-01‡ | -6.15E-01‡ | 2.97E-02 | |

| Priebe_etal_1998 | -1.69E-02 | 6.44E-01‡ | -8.90E-01‡ | -3.36E-01† | 1.46E-02 | |

| Type 5 | Fox_etal_2002 | 2.05E+00‡ | -8.28E-01‡ | 1.26E+00‡ | -2.12E-01† | -7.79E-01‡ |

| TenTusscher_etal_2006 | 5.20E-02 | 3.33E-01† | -4.59E-01† | -1.15E-01† | 2.43E-02 | |

| Fink_etal_2008 | 4.86E-02 | 3.33E-01† | -4.11E-01† | -8.53E-02 | 2.10E-02 |

† The relative difference is between 10% and 50%

‡ The relative difference is more than 50%

[Ca 2+]i differs substantially among the original EP models (without contraction) as shown in Table 5. For example, for systolic [Ca 2+]i, Grandi_etal_2010 and Shannon_etal_2004 have values in the [0.30,0.50]×10−3 mM range while Faber_etal_2000 is up to four times larger at 2.00×10−3 mM; for diastolic [Ca 2+]i, the maximum value is 2.00×10−3 mM for Faber_etal_2000 and the minimum value is 3.82×10−4 mM for Grandi_etal_2010, which is one fifth of the maximum value.

The original models that include dynamic Ca 2+ troponin buffers (Type One: Fig 2 panels (a) and (b); Type Two: panel (c); and Type Three: panel (d)) do not exhibit a significant change in the shape of the priming [Ca 2+]i transient after implementing contraction (adding NL96 model), but the models with instantaneous, or no Ca 2+ troponin buffers (Type Four: panel (e); and Type Five: panel (f)), demonstrate large differences in the [Ca 2+]i transient shape.

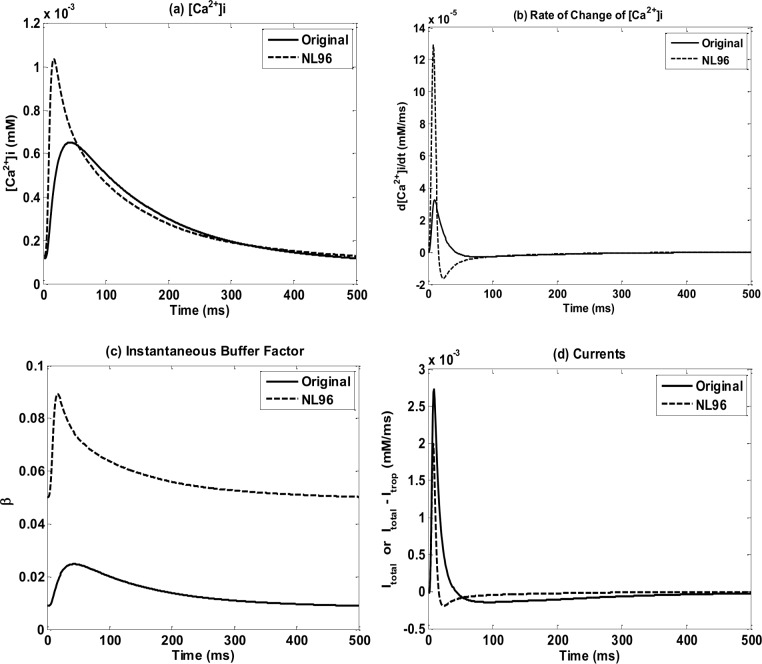

The most significant change tended to be an increase in the maximum [Ca 2+]i, always accompanied by a decrease in the time of this peak (t peak). As shown in Table 7, all six models with dynamic Ca 2+ troponin buffers have relative differences of less than 10% in systolic [Ca 2+]i and five out them have relative differences less than 10% in t peak. On the other hand, among the eight models with instantaneous or none Ca 2+ troponin buffers, six models show differences larger than 50% and none has a difference less than 10% in systolic [Ca 2+]i; in t peak, one of the eight models (Fink_etal_2008) has a relative difference less than 10% and three of them have differences of more than 50%. In addition, except for one model (Fox_etal_2002), all of them have positive relative differences in systolic [Ca 2+]i, indicating a systolic [Ca 2+]i increase after the implementation of the NL96 contraction; and all eight models have negative Δt peak, meaning the time of the peak is decreased by the implementation of contraction. The increase in maximum [Ca 2+]i and the decrease in t peak in models with instantaneous Ca 2+ troponin buffers after the implementation of NL96 (Fig 2, S2 File) is due to an increased and fast rate change of the intracellular calcium after its dynamics has been modified from Eqs 9 and 10 (before the implementation) to Eqs 11 and 12 (after the implementation) to account for the contraction. Fig 3(A) and 3(B) shows, as an example, the [Ca 2+]i and d[Ca 2+]i / dt respectively for the Ohara_etal_2011 model before (solid lines) and after (dashed line) the NL96 implementation. It can be seen that after the implementation of NL96: (i) the instantaneous buffer factor β increases due to the elimination of the instantaneous Ca 2+ troponin buffer from the denominator (see Eqs 10 and 12); and (ii) the flux is reduced due to the addition of the negative dynamic Ca 2+ troponin flux (see Eqs 9 and 11). The flux decreases by less than 50% of the original value (Fig 3(D)) but β increases by more than 200% (Fig 3(C)) resulting in an sharp increase in [Ca 2+]i amplitude. And the time for β to reach its peak is clearly shortened, resulting in the decrease of [Ca 2+]i peak (t peak).

Fig 3. Ca 2+ shape changes for models with instantaneous buffers.

Figures show the O’hara_etal_2008 model for: (a) [Ca 2+]i (grey lines) and d[Ca 2+]i / dt (black lines), before (solid lines) and after (dash lines) the implementation of NL96; (b) zoom in of d[Ca 2+]i / dt; (c) the instantaneous buffer factor β before (solid line) and after (dash line) the implementation of NL96; (d) intracellular Ca 2+ flux before (solid line) and after (dash line) the implantation of NL96.

Results for the priming [Ca 2+]i duration (t 1/2) are similar to those of systolic [Ca 2+]i (see Table 7). All six models that have dynamic Ca 2+ troponin buffers show little change in t 1/2 (less than 10%). Among the eight models with instantaneous or no Ca 2+ troponin buffers, six have differences more than 50% and none has a difference less than 10%. Seven out of eight have negative Δt 1/2, indicating the shortening in the time duration when [Ca 2+]i stays above half the amplitude. This large difference in t 1/2 is closely related to the change in systolic [Ca 2+]i. A sharp increase in systolic [Ca 2+]i greatly raises the half amplitude level (see the definition of the half amplitude level in Method section); this together with the large and narrow spike in [Ca 2+]i generated by the inclusion of contraction, significantly decrease the time duration where [Ca 2+]i stay above the half amplitude level.

The diastolic [Ca 2+]i and the Ca 2+ charge (Q) during one beat are the two parameters that do not change much after implementing NL96 contraction in all of the models. Thirteen out of fourteen models have diastolic [Ca 2+]i changes of less than 10%, with only one model having a difference larger than 50% (Fox_etal_2002). Q for eleven out of fourteen models changes by less than 10% and only one model (Fox_etal_2002) has a change of more than 50% (see Table 7).This is because, although the systolic [Ca 2+]i is greatly increased for models with instantaneous or none Ca 2+ troponin buffers, its increase is localized to a relatively narrow spike with an area that is negligible comparing with that of the rest of the [Ca 2+]i transient.

Models with dynamic buffers show significant Postextrasystolic Potentiation in [Ca 2+]i

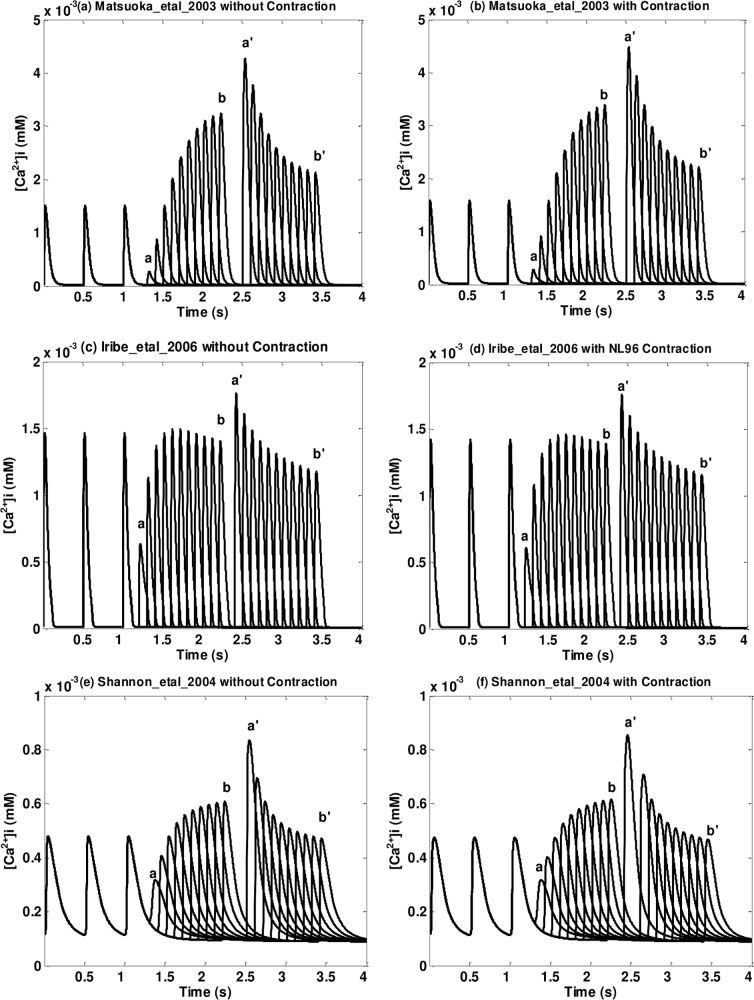

Postextrasystolic potentiation exists in intracellular Ca 2+ transients, where giving a fixed and long enough PESI, as the ESI increases, the amplitudes of the [Ca 2+]i of the ES beats will increase while the PES beats will show the opposite trend. Representative examples of the differences in [Ca 2+]i postextrasystolic potentiation before and after the implementation of NL96 contraction of Type One and Two (Type Three, Four, and Five) models are shown in Fig 4 (Fig 5). Figures for all models are in S3 File. ES beats with different ESIs are labeled from a to b; PES beats with a fixed PESI are labeled from a' to b' (see Step Three in Pacing Protocol in the Methods section); a and a' (b and b') correspond to ES and PES paired beats for the shortest (longest) ESI.

Fig 4. Postextrasystolic potentiation in [Ca 2+]i transient for three models of Type One and Two.

(a) (b) Matsuoka_etal_2003 without/with contraction; (c) (d) Iribe_etal_2006 without/with contraction (NL96); (e) (f) Shannon_etal_2004 without/with contraction. The first three beats are priming beats; from beat a to beat b are ES beats with different ESIs; from a' to b' are PES beats with a fixed PESI (fully restituted PESI, defined in Step Three in the Pacing Protocol of the Methods section); a and a' are corresponding ES and PES beats; so are b and b'. Note that each pair of figures (without/with contraction) has the same axis range.

Fig 5. Postextrasystolic potentiation in [Ca 2+]i transient for three models of Type Three, Four and Five.

(a) (b) Mahajan_etal_2008 without/with contraction; (c) (d) O’hara_etal_2006 without/with contraction; (e) (f) TenTusscher_etal_2004 without/with contraction. As in the previous figure, the first three beats are priming beats; from beat a to beat b are ES beats with different ESIs; from a' to b' are PES beats with a fixed PESI And each pair of figures (without/with contraction) has the same axis range.

From Figs 4 and 5 and S3 File we can see that models with dynamic Ca 2+ troponin buffers show a significant postextrasystolic potentiation in the [Ca 2+]i transients. As ESI increases, the amplitudes of the ES beats increase while the corresponding PES beats decrease. In addition, there’s no notable difference in [Ca 2+]i transient before and after the implementation of NL96 contraction (see Fig 4 and S3 File). On the other hand, models with instantaneous Ca 2+ troponin buffers do not show a significant postextrasystolic potentiation in the [Ca 2+]i transients. Among the eight models, only one model (Livshitz_etal_2007, see S3 File) shows notable amplitude change in both ES beats and PES beats. Three models (Hund_etal_2004, Faber_etal_2000 and Ohara_etal_2011, see Fig 5 and S3 File) show increase in ES beats but no noticeable decrease in PES beats. Four models (Priebe_etal_1998, Fox_etal_2002, TenTusscher_etal_2006 and Fink_etal_2008, see Fig 5 and S3 File) show neither considerable increase in ES beats nor decrease in PES beats. Note that these types of models, as discussed before, show a change in the shape of the [Ca 2+]i when contraction is included. However it doesn’t change the postextrasystolic potentiation behavior much, namely, if the original model has a clear PESP trend, after the implementation, the new model will still maintain that behavior and vice versa.

Contraction Results

To investigate how well our EP models with updated contraction can represent postextrasystolic dynamics, we calculated the four characteristic curves, described in the Methods, for all fourteen models with the NL96 contraction and compared them with the experimental data from Yue et al.[22]. Note that we did not show any CaTRPN transient because they are linearly related to the contraction in isometric condition[23].

Postextrasystolic Mechanical Restitution Curve (MRC pes)

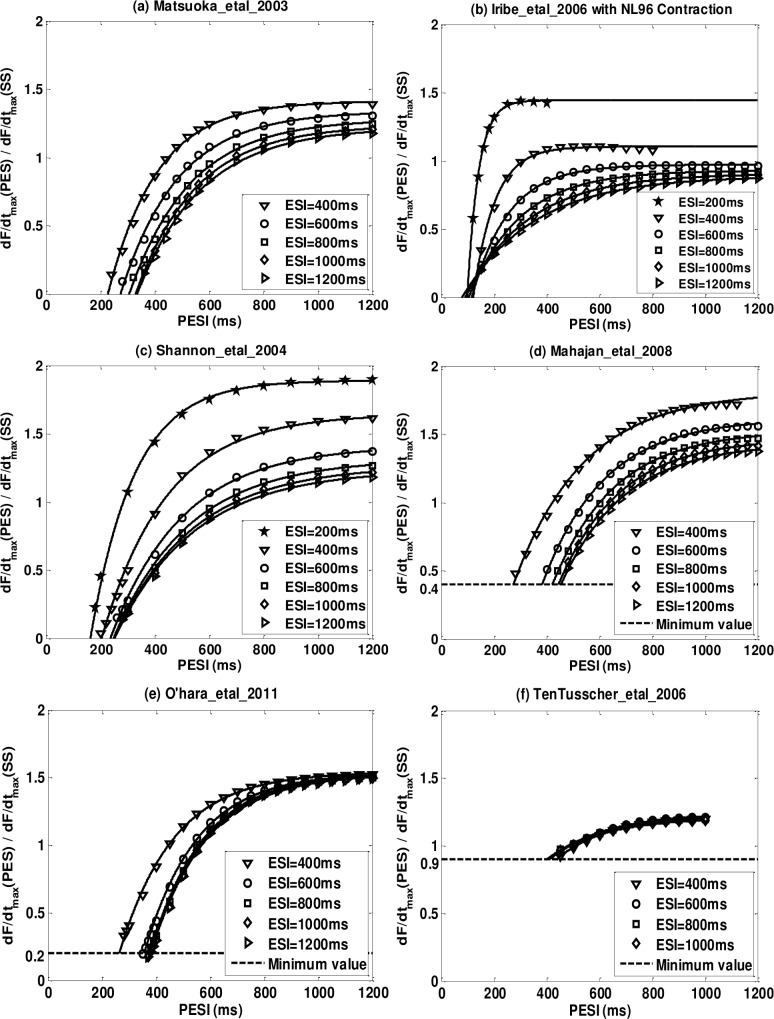

Representative examples of MRC pes (dF / dt max (PES) / dF / dt max (SS)) for six models are shown in Fig 6. For all the models, MRC pes are given in S4 File.

Fig 6. Representative postextrasystolic mechanical restitution curves (MRC pes) for six models after implementation of the NL96 contraction.

(a) Matsuoka_etal_2003; (b) Iribe_etal_2006; (c) Shannon_etal_2004; (d) Mahajan_etal_2008; (e) O’hara_etal_2011; (f) TenTusscher_etal_2006.

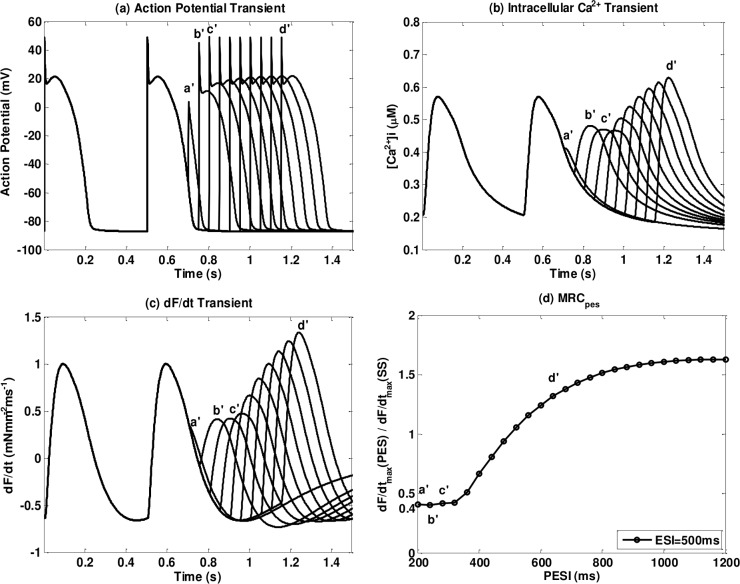

For all models MRC pes is well described (r2>0.99; averaged over all ESI values) by a monotonically increasing curve with respect to PESI (Eq 15) as shown in Table 8, after the elimination of some data points (see the example of Mahajan_eral_2008 below). However not all models were consistent with the experimental findings of Yue et al.[22] whose C 0 = 0. Among the six models with dynamic Ca 2+ troponin buffers (Type One, Two, Three), four satisfy this condition, while among the eight models with instantaneous or none Ca 2+ troponin buffers (Type Four and Five), only one satisfies C 0 = 0 (see Table 8). Here we provide a brief explanation why C 0 does not go to zero for some models in our simulations. We use Mahajan_etal_2008 with NL96 as an example to demonstrate. In Fig 7(A), 7(B) and 7(C) we plot the Action Potential (AP), [Ca 2+]i transient and normalized dF / dt transient of Mahajan_etal_2008 with NL96 for ESI = 500ms. The first beat is the steady priming beat, the second beat is the ES beat with ESI = 500ms and from a' to d' are PES beats with PESI from 200 to 650ms. We can observe that the dF / dt max increases with PESI from beat c' to d' but there is no well-defined trend before c'. Beat a' and b' are not clearly separated from the ES beat and a' is even almost fused into the ES beat. However, even though beat a' is very close to the ES beat, dF / dt max still does not go to zero. We plot normalized dF / dt max (normalize to steady priming beat) for ESI = 500ms and PESI ranges from 200ms to 1200ms in Fig 7(D). We can see that dF / dt max stops decreasing when PESI is below 300ms and the minimum value is about 0.4. In order to fit this into Eq 15 we exclude data with PESI lower than 300ms and set C 0 = 0.4. That is the reason for Mahajan_etal_2008 and other eight models, that C 0 does not go to zero and also an example of how we choose the shortest ESI and PESI values.

Table 8. Contraction parameters: MRCpes and PESPC.

| Model Type | Model Name | MRCpes Mean r square | MRCpes C0 | PESPC_B | PESPC_A | PESPC_to,es (ms) | PESPC_Tpespc (ms) | PESPC r square |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Experiment | Yue et al 1985 • | ——- | 0 | 1.05±0.13 | 1.68±0.32 | 284±32 | 176±18 | ——- |

| Type 1 | Matsuoka_etal_2003 | 0.9967 | 0 | 1.13±0.05 | 0.34±0.04 XX | 260±6 | 704±156 XX | 0.9944 |

| Iribie_etal_2006 | 0.9953 | 0 | 0.90±0.01 ** | 1.01±0.09 ** | 119±6 XX | 184±13 | 0.9969 | |

| Type 2 | Shannon_etal_2004 | 0.9988 | 0 | 1.22±0.01 ** | 0.83±0.02 *** | 219±6 ** | 263±9 XX | 0.9996 |

| Grandi_etal_2010 | 0.9991 | 0 | 1.47±0.01 XX | 0.65±0.02 XX | 297±4 | 221±13 ** | 0.9983 | |

| Type 3 | Mahajan_etal_2008 | 0.9987 | 0.4 XX | 1.00±0.03 | 0.47±0.03 XX | 344±6 ** | 346±49 XX | 0.9938 |

| Iyer_etal_2004 | 0.9987 | 0.4 XX | 1.49±0.05 XX | 0.48±0.05 XX | 366±3 *** | 608±96 XX | 0.9933 | |

| Type 4 | Hund_etal_2004 | 0.9991 | 0 | 1.47±0.01 XX | 0.02±0.01 XX | 233±4 ** | 471±320 X | 0.9043† |

| Faber_etal_2000 | 0.9986 | 0.7 XX | 0.74±0.01 *** | -0.01±0.01 XX | 334±6 ** | 323±46 XX | 0.9865† | |

| Livshitz_etal_2007 | 0.9998 | 0.5 XX | 0.80±0.01 ** | 0.04±0.01 XX | 312±1 | 413±100 XX | 0.9814† | |

| Ohara_etal_2011 | 0.9988 | 0.2 XX | 1.33±0.01 *** | 0.02±0.01 XX | 326±3 ** | 322±196 X | 0.8848‡ | |

| Priebe_etal_1998 | 0.9992 | 1.1 XX | 0.77±0.01 *** | -0.00±0.01 XX | 566±4 XX | 232±7809 X | 0.0048‡ | |

| Type 5 | Fox_etal_2002 | 0.9991 | 0.5 XX | 1.32±0.01 ** | 0.01±0.01 XX | 321±4 ** | 328±94 XX | 0.9156† |

| TenTusscher_etal_2006 | 0.9971 | 0.9 XX | 0.01±32.8 X | 0.33±32.8 X | 423±9 XX | 1.04e4±1e6X | 0.4278‡ | |

| Fink_etal_2008 | 0.9977 | 0.9 XX | 0.31±0.01 XX | 0.01±0.01 XX | 392±6 XX | 190±121 X | 0.8208‡ |

** Model’s 95% confidence bound overlaps the mean±2*SD value in Yue et al 1985 experiment

***Model’s 95% confidence bound overlaps the mean±3*SD value in Yue et al 1985 experiment

XX Model’s 95% confidence bound does not overlap the mean±n*SD value in Yue et al 1985 experiment with n≤3

X Model’s 95% confidence bound overlaps the mean±SD value in Yue et al 1985 but the bound is more than 50% of the center value

† 0.9 ≤r2 ≤0.99

‡ r2 <0.9

• Plus/minus is standard deviation. The other plus/minus are 95% confidence range

Fig 7. Details for cases where C 0 does not go to zero.

We use as example the Mahajan_etal_2008 for ESI = 500ms: (a) the action potential (AP), (b) [Ca 2+]i transient; (c) normalized dF / dt transient (d) normalized dF / dt max of the PES beats. In (a) (b) and (c), the first beat is the priming beat; the second beat is the ES beat with ESI = 500ms; from a' to d' are PES beats with PESI ranges from 200ms to 650ms.

The experimental results of Yue et al.[22] showed that the fully restituted plateau value of MRC pes (CR max,pes) decreased as ESI increased. From Fig 6 and S4 File we can see that all models with dynamic Ca 2+ troponin buffers show unique plateau values for different ESIs while models with instantaneous or no Ca 2+ troponin buffers converge to the same plateau values for different ESIs; this property will be further discussed in the PESPC subsection.

The time constant for MRC pes (T mrc,pes) did not vary much as a function of ESI in the experiment of Yue et al.[22]. In addition, a leftward shift of the MRC pes was observed as ESI decreased, presented as an increase of t o,pes as ESI increased. The fourteen models behave differently regarding these two parameters. We will discuss these in detail in the t o,pes and T mrc,pes subsections.

Postextrasystolic Potentiation Curve (PESPC)

Fig 8 shows representative postextrasystolic potentiation curves (PESPCs) for six models. Figures for all models can be found in S5 File. To provide a better picture of the amplitude and time constant of the PESPC we simultaneously plot the PESPC and the Extrasystolic Mechanical Restitution Curve (MRC es) as in Yue et al.[22]. Note that for those models with C 0 ≠ 0 in the MRC pes, we have shifted the curves upward by C 0 when plotting the PESPC (star *) on the same graph with the MRC es (open circle o) for comparison. We also use 95% confidence bounds as error bars for each data point on PESPC, which is the fitting confidence bound for CR max,pes of each ESI value. Note that confidence bounds are relatively small compared to the scale of the graph.

Fig 8. Representative postextrasystolic potnetiation curve (PESPC, circles o) and extrasystolic mechanical restitution curve (MRC es, stars *) for six models.

(a) Matsuoka_etal_2003; (b) Iribe_etal_2006; (c) Shannon_etal_2004; (d) Mahajan_etal_2008; (e) O’hara_etal_2011; (f) TenTusscher_etal_2006. 95% confidence bounds of CR max,pes are plotted as error bars on PESPC but since the confidence bounds are small compared to the entire scale, they are not clearly observed in the figures.

A list of all parameters for the curve fitting of Eq 16 are listed in Table 8 for all the models along with the experimental data of Yue et al.[22] to allow comparison between our simulation results and those from the experiments. The values without any symbol match the experiment results well. They are either parameters with 95% confidence bounds overlapping the mean plus/minus standard deviation (mean±SD) range from Yue et al.[22] or they have r2 values that are higher than 0.99. The double and the triple star (** and ***) means the 95% confidence bound overlaps Yue et al.[22] data’s mean±2*SD and the mean±3*SD respectively. The X mark means the confidence bound overlaps the mean±SD but the confidence bound is too large (more than 50% of the center value) so that we do not consider this as a real overlapping. The double X mark (XX) means the confidence bound does not overlap the mean±n*SD from Yue experiment with n≤3.The single-dagger (†) means the r2 is less than 99% but more than 90% and the double-dagger (‡) means it’s less than 90%.

The experiments of Yue et al.showed that PESPC decreased monoexponentially to a plateau level as ESI increases (Eq 16 and Fig 1(B)), meaning that when PESI is fixed and long enough, the maximum force changing rates of the PES beats will decrease as ESI increases. Models with dynamic Ca 2+ troponin buffers (Type One, Two and Three) have PESPCs well described by Eq 16; all six models have r2 values larger than 0.99. On the other hand, models with instantaneous or no Ca 2+ troponin buffers (Type Four and Five) are not well fit by Eq 16. Four of the eight models have r2 values lower than 0.9 with one of them as low as 0.0048 (Priebe_etal_1998). However, the poor quality of the fitting is not evident on Fig 8 or S5 File because the amplitude of the PESPC is much smaller than the scale of the figure.

The plateau levels (B) of CR max,pes for the fourteen contraction models are more similar to the experiment results compared to the other parameters. In Yue et al.[22], the mean value (± SD) for B is 1.05±0.13. In our simulations, two out of the six models with dynamic Ca 2+ troponin buffers (Type One, Two and Three) have 95% confidence bounds overlap the mean±SD range of Yue et al.[22] and four have confidence bounds overlap the mean±2*SD range. On the other hand, only two out of eight models with instantaneous or no Ca 2+ troponin buffers (Type Four and Five) have 95% confidence bounds overlap the mean±2*SD range.

Parameter A has the least matching degree with Yue et al.[22] where the mean value (± SD) is 1.68±0.32. Only one out of the six models with dynamic Ca 2+ troponin buffers (Type One, Two and Three) have 95% confidence bounds overlap the mean±2*SD range from Yue paper and none of the models with instantaneous or none Ca 2+ troponin buffers have confidence bounds overlapping this range (see Table 8). The values of A from our contraction models are significantly smaller than Yue paper. This feature is well depicted in Fig 8 and S5 File in which the PESPCs of the models with instantaneous buffers have slopes of approximate zero while in the Yue et al. paper there exhibited a pronounced monoexponentially decay (Fig 1(B)). The insufficient change in fully-restituted contractile strength of postextrosystoles with respect to varied ESIs indicates a clear limitation of these models as we will further comment in the discussions section.

t o,es is obtained by calculating where the Extrasystolic Mechanical Restitution Curve (MRC es) intercepts the line . The mean value (±SD) in the Yue et al.[22] is 284±32ms. Four out of six models with dynamic Ca 2+ troponin buffers (Type One, Two and Three) and five out of eight models with instantaneous buffers (Type Four and Five) are in the mean±2*SD range. For this parameter, it seems that the dynamic buffers do not show much advantage over instantaneous buffers. However, in the Yue et al. paper, this interception is where MRC es intercepts with the line , so are four out of the six models with dynamic Ca 2+ troponin buffers. But for most models with instantaneous buffers, this parameter is where MRC es intercepts with the line with C 0 ≠ 0. Therefore models with dynamic buffers still match this parameter better to the experimental data of Yue et al.[22].

The mean value (± SD) of the time constant for PESPC (T pespc ) is 176±18ms in Yue et al.[22]. Only two out of the six models with dynamic Ca 2+ troponin buffers (Type One, Two, Three) and none of the models with instantaneous or none buffers (Type Four and Five) have 95% confidence bounds that overlap the experimental mean±2*SD range. Ten other models have time constants much larger(50% more) than Yue et al.[22]. This parameter is also the least well fit for models with instantaneous or no Ca 2+ troponin buffers; five out of eight models have 95% confidence bounds larger than 50% of the center values, indicating a poor fit.

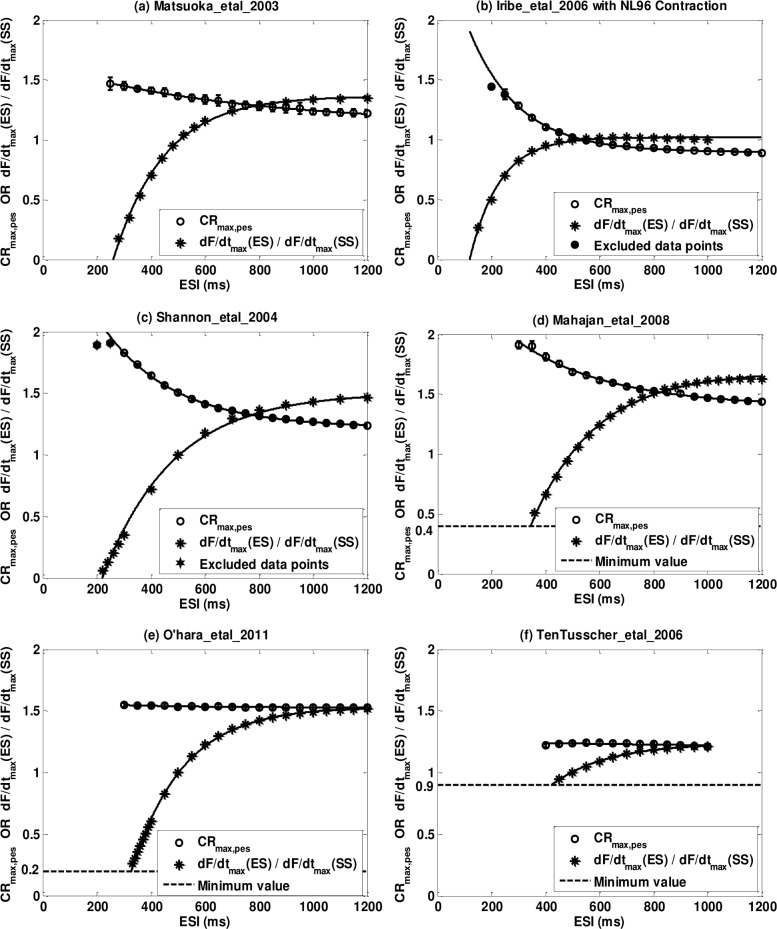

Minimum-value Axis Intercept Curve (t o,pes)

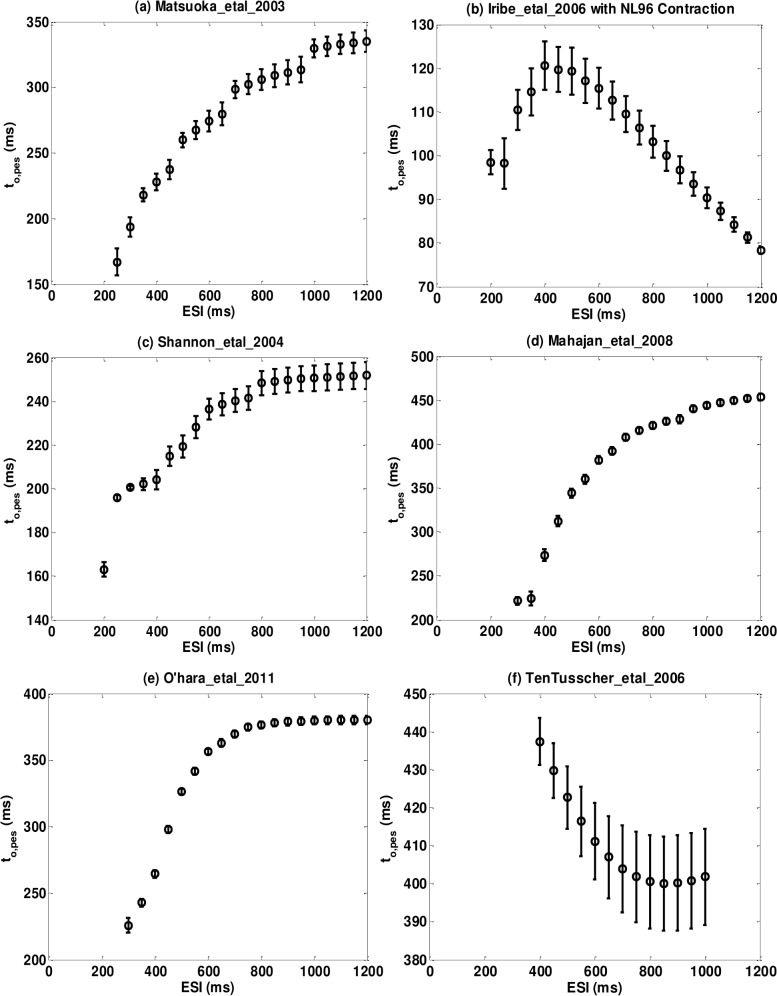

Fig 9 shows Minimum-value Axis Intercept Curves for six models. Open circles (o) are t o,pes for different ESI values. Error bars are 95% confidence bounds. Figures for all models are provided in the S6 File and the summarized data is in Table 9.

Fig 9. Representative minimum-value axis intercept curve (t o,pes) for six models. (a) Matsuoka_etal_2003; (b) Iribe_etal_2006; (c) Shannon_etal_2004; (d) Mahajan_etal_2008; (e) O’hara_etal_2011; (f) TenTusscher_etal_2006. 95% confidence bounds of t o,pes are plotted as error bars.

Table 9. Contraction parameters: to,pes and Tmrc,pes.

| Model name | to,pes | Tmrc,pes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trend w.r.t. ESI | Range(ms) | Tmrc,es(ms) | Mean±SD • | Tpespc-Tmrc,es(ms) | |

| Yue_etal_1985 • | Monotonic increase | 180–420 | 181±41 | 1.01±0.12 | 13±23 |

| Matsuoka_etal_2003 | Monotonic increase | 167–335 | 187±13 | 1.15±0.12 | 517±156 XX |

| Iribie_etal_2006 | Not monotonic XX | 78–120 XX | 110±9 ** | 1.52±0.71 | 74±13 *** |

| Shannon_etal_2004 | Monotonic increase | 163–252 | 262±16 ** | 0.98±0.17 | 1±16 |

| Grandi_etal_2010 | Monotonic increase | 245–350 | 234±10 ** | 1.01±0.11 | -13±13 |

| Mahajan_etal_2008 | Monotonic increase | 221–454 | 238±14 ** | 1.04±0.08 | 108±49 ** |

| Iyer_etal_2004 | Monotonic increase | 305–498 | 333±10 XX | 1.04±0.04 | 275±96 XX |

| Hund_etal_2004 | Monotonic increase | 126–242 | 234±9 ** | 1.00±0.02 | 237±320 ※ |

| Faber_etal_2000 | Monotonic decrease XX | 297–342 | 300±13 *** | 1.02±0.04 | 23±46 |

| Livshitz_etal_2007 | Monotonic increase | 232–333 | 203±3 | 1.02±0.06 | 210±100 XX |

| Ohara_etal_2011 | Monotonic increase | 226–380 | 193±8 | 1.04±0.02 | 129±196 ※ |

| Priebe_etal_1998 | Not monotonic XX | 377–624 | 438±14 XX | 1.04±0.03 | -206±7809 ※ |

| Fox_etal_2002 | Not monotonic XX | 244–380 | 370±8 XX | 1.00±0.02 | -42±94 ※ |

| TenTusscher_etal_2006 | Monotonic decrease XX | 402–437 | 209±25 | 1.04±0.04 | 1.02e4±1e6※ |

| Fink_etal_2008 | Monotonic decrease XX | 341–420 | 256±18 ** | 1.06±0.03 | -66±121 ※ |

** Model’s 95% confidence bound overlaps the mean±2*SD value in Yue et al 1985 experiment

*** Model’s 95% confidence bound overlaps the mean±3*SD value in Yue et al 1985 experiment

XX Model’s 95% confidence bound does not overlap the mean±n*SD value in Yue et al 1985 experiment with n≤3

※ Model’s 95% confidence bound overlaps the mean±SD value in Yue et al 1985 but the bound is more than 3*SD

• Plus/minus is standard deviation. The other plus/minus are 95% confidence range.

In the Yue et al. paper[22], t o,pes increased as ESI increased. They explained this trend by suggesting that the refractory period is an increasing function of ESI[22]. Five out of six models with dynamic buffers (Type One, Two and Three) show the same trend as Yue et al. paper with t o,pes increasing exponentially with ESI; only the Iribe_etal_2006 model shows a non-monotonic behavior. Three out of eight models with instantaneous buffers (Type Four and Five) show the same trend as Yue et al. (Hund_etal_2004, Livshitz_etal_2007 and O’hara_etal_2011) while three models show a monotonically decreasing trend (Faber_etal_2000, TenTusscher_etal_2003 and Fink_etal_2008) and two (Priebe_etal_1998 and Fox_etal_2002) do not have monotonic behaviors. The Ranges of t o,pes of the models match Yue et al. paper well as thirteen out of fourteen models fall within the experimental range.

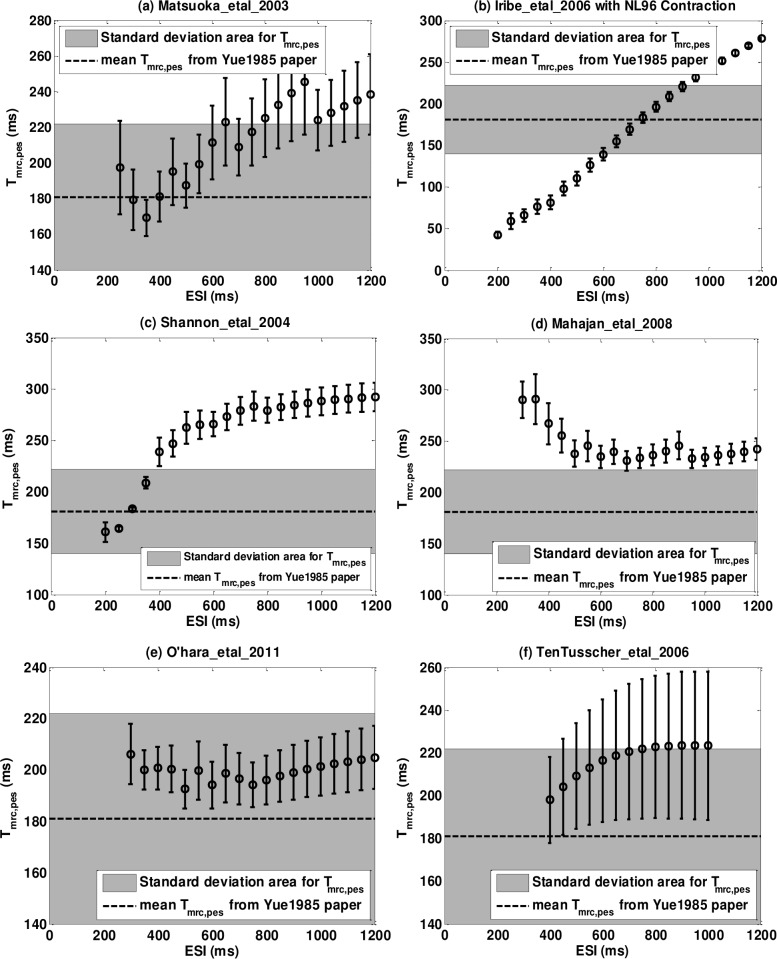

Time Constant Curve (Tmrc,pes)

Fig 10 shows six Time Constant Curves, i.e. time constants of MRC pes (T mrc,pes) vs ESI for 6 models, where the dash line indicates the mean T mrc,es from the Yue et al. paper; the grey area denotes the range of the mean±SD range. Open circles (o) are T mrc,pes from curve fitting for different ESI values. Error bars are 95% confidence bounds. Figures for all the models are in S7 File. There were two major results in Yue et al.[22] regarding T mrc,pes. First, T mrc,pes varied little with ESI; the mean (± SD) T mrc,es was 181±41ms and the mean normalized T mrc,pes (normalize to T mrc,es) was 1.01±0.12. In our simulations, all of the models have their normalized time constant values overlap the mean±2*SD range from Yue paper while ten of the models have their T mrc,es (identical to T mrc,pes with ESI = 500ms in simulations) overlap the mean±2*SD range from Yue paper. Therefore our contraction models fit this property with Yue paper quite well. The second major result from Yue paper is that the time constants of PESPC and MRC pes were close; the mean difference between the two time constants (± SD) was 13±23ms. Models with dynamic Ca 2+ troponin buffers (Type One, Two and Three) are more consistent with the experiments than instantaneous buffers (Type Four and Five) in this respect. Three out of six models with dynamic buffers have 95% confidence bounds that overlap Yue’s mean±2*SD range while only one out of eight models with instantaneous buffers overlaps that. Six of them have large 95% confidence bounds inherited from the large T pespc bounds, so we marked them by a symbol ※, indicating the 95% confidence bounds overlap Yue’s mean±SD but the confidence bound is so large (more than 3*SD) that we do not consider this as a real overlapping.

Fig 10. Representative time constant for MRC pes curve (T mrc,pes) for six models.

(a) Matsuoka_etal_2003; (b) Iribe_etal_2006; (c) Shannon_etal_2004; (d) Mahajan_etal_2008; (e) O’hara_etal_2011; (f) TenTusscher_etal_2006. Error bars are 95% confidence bounds. The dash line indicates mean T mrc,pes for ESI = 460ms from Yue et al. The grey area denotes their standard deviation range.

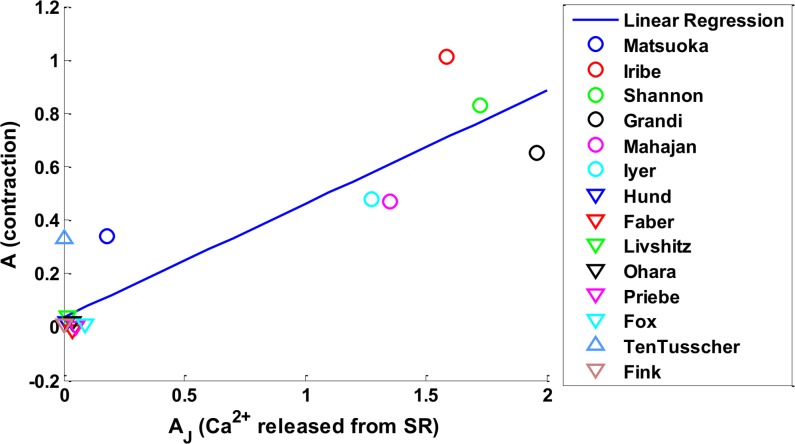

Underlying Mechanism for PESP

There is a clear resemblance between the intracellular Ca 2+ dynamic and force dynamics. And since the Ca 2+ released from SR (J rel) is the main source for intracellular Ca 2+, we propose that J rel dynamics, which depends on RyR, , among others, is the primary determinant of PESP dynamics.

To verify this hypothesis, we analyzed, for each model, the correlation between the dependence of the potentiation in Ca 2+ released from SR (J rel) and the contractile strength on pacing intervals. In this study we have shown two sets of curves demonstrating the potentiation strength: the Postextrasystolic Mechanical Restitution Curve (MRC pes) and Postextrasystolic Potentiation Curve (PESPC). The MRC pes demonstrates how postextrasystolic contractile strength changes with respect to various PESI for a fixed ESI. From Fig 6 and S4 File, it can be seen the consistency of the increasing trend of the normalized force changing rate with respect to PESI for all models studied. However, the PESPC, which shows how postextrasystolic contractile strength changes with respect to various ESI values for a fixed and long PESI, differs among models: models with dynamic buffers showed significant variation in contractile strength with respect to ESI while models with instantaneous buffers showed little variation (Fig 8 and S5 File). The amplitude (parameter A) in PESPC captures this difference. Since we are interested in what causes the difference in models, we studied the correlation between the Ca 2+ released from SR (J rel) and the contractile strength of the postextrasystoles with various ESI and fixed PESI. We designed an analogous parameter A J for the J rel amplitude. Similar to our dF / dt max fit, for a fixed ESI, we first fit the normalized J rel_max (to the prime beats) of the postextrasystolic beats to a mono-exponentially increasing curve with respect to PESI (analogous to MRC pes). For most models, J rel_max was well described by a mono-exponential increasing curve, similar to the contractile strength. Then we fit the plateau values of these curves to a mono-exponentially decreasing curve with respect to ESI (analogous to PESPC); we define the amplitude of this curve as A J. Models with larger A J suggest that their fully-restituted J rel_max vary with respect to ESI. Therefore the correlation between A and A J can be used as a gauge for the correlation between the dependence of J rel and the contractile strength on pacing intervals. We performed a linear regression for A J and A for thirteen (out of the fourteen) electromechanical models as shown in Fig 11. We found a strong positive correlation (r2 = 0.848) between the two parameters. In addition, data from models with instantaneous buffers clustered around the origin while data from models with dynamic buffers were distributed along the regression curve. This means for models with instantaneous buffers, the insufficient variation in the fully-restituted postextrasystolic contractile strength responding to various ESI is a direct result of the J rel dynamics. Note that the model excluded from the linear regression was TenTusscher_etal_2006 (upward triangular mark in Fig 11) because the curve fitting for parameter A in this model is not reliable due to its large 95% confidence bound (see Table 8).

Fig 11. Correlation between the potentiation in Jrel and contractile strength.

The Postextrasystolic Potentiation Curves (PESPC) amplitude of contractile strength (A) vs that of calcium released from SR (A J).

Discussion

Simulations of electrical therapies for HF (e.g., CRT and CCM) require models that accurately reproduce the excitation-contraction coupling that occurs in the cardiac myocyte. While action potential duration restitution curves tend to be used to help validate EP models, there has been no systematic method to validate cellular contraction models. We suggest that the PESP protocol can be used in the validation process of mathematical models of cellular electromechanics and we present a methodology to include mechanics into cellular EP models of various types and compare results among the models with and without contraction.

The results from this study suggest four reasons for which electrophysiology models with dynamic Ca 2+ troponin buffers are much better candidates to implement contraction than EP models with instantaneous or none Ca 2+ troponin buffers.

First, the complexity in implementation is greatly reduced since the original models are already equipped with dynamic equations for Ca 2+ troponin buffers. Type Two and Type three models only take one step in the implementation flowchart while Type Four and Type Five require one or two more steps to add in instantaneous Ca 2+ troponin buffers and change the instantaneous ones into a dynamic form (see S1 File).

Second, the inclusion of contraction does not disturb properties in the original models. The [Ca 2+]i shape shows minimum change for models with dynamic buffers while it is largely distorted for models with instantaneous or none Ca 2+ troponin buffers (Fig 2 and S2 File). This is closely related to the first benefit as it requires adding extra terms into Type Four and Type Five models to incorporate contraction and therefore Ca 2+ shapes are more likely to be unphysiologically deformed.

Third, models with dynamic Ca 2+ troponin buffers show clear postextrasystolic potentiation in [Ca 2+]i with or without contraction implemented (see Figs 4 and 5 and S3 File). Therefore these models show desired variation in contractile strength of extrasystoles and postextrasystoles because of the close relationship between Ca 2+ and contraction.

Fourth, contraction properties of models with dynamic Ca 2+ troponin buffers fit experimental results better [22] (see Figs 6, 8, 9 and 10). This has been shown in the four characteristic curves (Postextrasystolic Mechanical Restitution Curve (MRC pes); Postextrasystolic Potentiation Curve (PESPC); Minimum-value Axis Intercept Curve (t o,pes) and Time Constant Curve (T mrc,pes)) and their various parameters.