Abstract

Bullying is the systematic abuse of power and is defined as aggressive behaviour or intentional harm-doing by peers that is carried out repeatedly and involves an imbalance of power. Being bullied is still often wrongly considered as a ‘normal rite of passage’. This review considers the importance of bullying as a major risk factor for poor physical and mental health and reduced adaptation to adult roles including forming lasting relationships, integrating into work and being economically independent. Bullying by peers has been mostly ignored by health professionals but should be considered as a significant risk factor and safeguarding issue.

Keywords: Child Abuse, Psychology, School Health, General Paediatrics, Outcomes research

Definition and epidemiology

Bullying is the systematic abuse of power and is defined as aggressive behaviour or intentional harm-doing by peers that is carried out repeatedly and involves an imbalance of power, either actual or perceived, between the victim and the bully.1 Bullying can take the form of direct bullying, which includes physical and verbal acts of aggression such as hitting, stealing or name calling, or indirect bullying, which is characterised by social exclusion (eg, you cannot play with us, you are not invited, etc) and rumour spreading.2–4 Children can be involved in bullying as victims and bullies, and also as bully/victims, a subgroup of victims who also display bullying behaviour.5 6 Recently there has been much interest in cyberbullying, which can be broadly defined as any bullying which is performed via electronic means, such as mobile phones or the internet. One in three children report having been bullied at some point in their lives, and 10–14% experience chronic bullying lasting for more than 6 months.7 8 Between 2% and 5% are bullies and a similar number are bully/victims in childhood/adolescence.9 Rates of cyberbullying are substantially lower at around 4.5% for victims and 2.8% for perpetrators (bullies and bully/victims), with up to 90% of the cyber-bullying victims also being traditionally (face to face) bullied.10 Being bullied by peers is the most frequent form of abuse encountered by children, much higher than abuse by parents or other adult perpetrators11 (box 1).

Box 1. Bullying screener.

- Direct bullying refers to harming others by directly getting at them. It is done by one or a group of pupils repeatedly against some children at school. These children:

- Are threatened or blackmailed or have their things stolen

- Are insulted or get called nasty names

- Have nasty tricks played on them/are subject to ridicule

- Are hit, shoved around or beaten up

- Relational bullying refers to damage relationships between friends and destroy status in groups to hurt or upset someone. Over and over again some children at school:

- Get deliberately left out of get-togethers, parties, trips or groups

- Have others ignore them, not wanting to be their friend anymore, or not wanting them around in their group

- Have nasty lies, rumours or stories told about them

- Cyberbullying is when someone tries to upset and harm a person using electronic means (eg, mobile phones, text messages, instant messaging, blogs, websites (eg, Facebook, YouTube) or emails)

- Have their private email, instant mail or text messages forwarded to someone else or have them posted where others can see them

- Have rumours spread about them online

- Get threatening or aggressive emails, instant messages or text messages

- Have embarrassing pictures posted online without their permission

(Answered for A, B, and C separately on this 4-point scale)

- How often have these things happened to you in the last 6 months?

- Never

- Not much (1–3 times)

- Quite a lot (more than 4 times)

- A lot (at least once a week)

- How often have you done these things to others in the last 6 months?

- Never

- Not much (1–3 times)

- Quite a lot (more than 4 times)

- A lot (at least once a week)

Victims: Happened to them: quite a lot/a lot; did to others: never/not much

Bully/victims: Happened to them: quite a lot/a lot; did to others: quite a lot/a lot

Bullies: Happened to them: never/not much; did to others: quite a lot/a lot

Bullying is not conduct disorder

Bullying is found in all societies, including modern hunter-gatherer societies and ancient civilisations. It is considered an evolutionary adaptation, the purpose of which is to gain high status and dominance,14 get access to resources, secure survival, reduce stress and allow for more mating opportunities.15 Bullies are often bi-strategic, employing both bullying and also acts of aggressive ‘prosocial’ behaviour to enhance their own position by acting in public and making the recipient dependent as they cannot reciprocate.16 Thus, pure bullies (but not bully/victims or victims) have been found to be strong, highly popular and to have good social and emotional understanding.17 Hence, bullies most likely do not have a conduct disorder. Moreover, unlike conduct disorder, bullies are found in all socioeconomic18 and ethnic groups.12 In contrast, victims have been described as withdrawn, unassertive, easily emotionally upset, and as having poor emotional or social understanding,17 19 while bully/victims tend to be aggressive, easily angered, low on popularity, frequently bullied by their siblings20 and come from families with lower socioeconomic status (SES),18 similar to children with conduct disorder.

How bullies operate

Bullying occurs in settings where individuals do not have a say concerning the group they want to be in. This is the situation for children in school classrooms or at home with siblings, and has been compared to being ‘caged’ with others. In an effort to establish a social network or hierarchy, bullies will try to exert their power with all children. Those who have an emotional reaction (eg, cry, run away, are upset) and have nobody or few to stand up for them, are the repeated targets of bullies. Bullies may get others to join in (laugh, tease, hit, spread rumours) as bystanders or even as henchmen (bully/victims). It has been shown that conditions that foster higher density and greater hierarchies in classrooms (inegalitarian conditions),21 at home22 or even in nations,23 increase bullying24 and the stability of bullying victimisation over time.25

Adverse consequences of being bullied

Until fairly recently, most studies on the effects of bullying were cross-sectional or just included brief follow-up periods, making it impossible to identify whether bullying is the cause or consequence of health problems. Thus, this review focuses mostly on prospective studies that were able to control for pre-existing health conditions, family situation and other exposures to violence (eg, family violence) in investigating the effects of being involved in bullying on subsequent health, self-harm and suicide, schooling, employment and social relationships.

Childhood and adolescence (6–17 years)

A fully referenced summary of the consequences of bullying during childhood and adolescence on prospectively studied outcomes up to the age of 17 years is shown in table 1. Children who were victims of bullying have been consistently found to be at higher risk for common somatic problems such as colds, or psychosomatic problems such as headaches, stomach aches or sleeping problems, and are more likely to take up smoking.39 40 Victims have also been reported to more often develop internalising problems and anxiety disorder or depression disorder.31 Genetically sensitive designs allowed comparison of monozygotic twins who are genetically identical and live in the same households but were discordant for experiences of bullying. Internalising problems was found to have increased over time only in those who were bullied,32 providing strong evidence that bullying rather than other factors explains increases in internalising problems. Furthermore, victims of bullying are at significantly increased risk of self-harm or thinking about suicide in adolescence.43 44 Furthermore, being bullied in primary school has been found to both predict borderline personality symptoms30 and psychotic experiences, such as hallucinations or delusions, by adolescence.37 Where investigated, those who were either exposed to several forms of bullying or were bullied over long periods of time (chronic bullying) tended to show more adverse effects.31 37 In contrast to the consistently moderate to strong relationships with somatic and mental health outcomes, the association between being bullied and poor academic functioning has not been as strong as expected.51 A meta-analysis only indicated a small negative effect of victimisation on mostly concurrent academic performance and the effects differed whether bullying was self-reported or by peers or teachers.47 Those studies that distinguished between victims and bully/victims usually reported that bully/victims had a slightly higher risk for somatic and mental health problems than pure victims.41 52 Furthermore, most studies considered bullies and bully/victims together; however, as outlined above, the two roles are quite different with bullies often highly competent manipulators and ringleaders, while bully/victims are described as impulsive and poor in regulating their emotions.53 We know little about the mental health outcomes of bullies in childhood, but there are some suggestions that they may also be at slightly increased risk of depression or self-harm,33 45 however, less so than victims. Similarly, the relationship between being a bully and somatic health is weaker than in bully/victims,39 or bullies have even been found to be healthier and stronger than children not involved in bullying.41 Bullying perpetration has been found to increase the risk of offending in adolescence;54 however, the analysis did not distinguish between bullies and bully/victims and did not include information about poly-victimisation (eg, being maltreated by parents). Bullies were also more likely to display delinquent behaviour and perpetrate dating violence by eighth grade.50

Table 1.

Consequences of involvement in bullying behaviour in childhood and adolescence on outcomes assessed up to 17 years of age

| Findings | Example references | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | Victims | Bullies | Bully/victims | |

| Health and mental health | ||||

| Anti-social personality disorder | No significant association was found between victims and delinquent behaviour. | Bullying perpetration was strongly linked to delinquent behaviour. | Bullying victimisation was associated with delinquent behaviour. | 26 |

| Anxiety | Pre-school peer victimisation increases the risk of anxiety disorders in first grade. Peer victimisation (especially relational victimisation) was strongly related to adolescents’ social anxiety. Moreover, peer victimisation was both a predictor and a consequence of social anxiety over time. However, Storch and colleagues’ results showed that overt victimisation was not a significant predictor of social anxiety or phobia and relational victimisation only predicted symptoms of social phobia. | – | – | 27–29 |

| Borderline personality symptoms (BPD) | Victims showed an increased risk of developing BPD symptoms. Moreover, a dose–response effect was found: stronger associations were identified with increased frequency and severity of being bullied. | – | – | 30 |

| Depression and internalising problems | Monozygotic twins who had been bullied had more internalising symptoms compared with their co-twin who had not been bullied. Peer victimisation was associated with higher overall scores, as well as increased odds of scoring in the severe range for emotional and depression symptoms. Victims were also more likely to show persistent depression symptoms over a 2-year period. Moreover, a dose–response relationship was found showing that the stability of victimisation and experiencing both direct and indirect victimisation conferred a higher risk for depression problems and depressive symptom persistence. A meta-analytic study showed significant associations between peer victimisation and subsequent changes in internalising problems, as well as significant associations between internalising problems and subsequent changes in peer victimisation. | Being a bully was not a predictor of subsequent depression among girls but was among boys. | Bully/victims exhibited significantly greater internalising problems. | 31–36 |

| Psychotic experiences | Being bullied increased the risk of psychotic experiences. Also a dose–response relationship was found where stronger associations were identified with increased frequency, severity and duration of being bullied. | – | – | 37 38 |

| Somatic problems | Children and adolescents who are bullied have a higher risk for psychosomatic problems such as headache, stomach ache, backache, sleeping difficulties, tiredness and dizziness. They were also more likely to display sleep problems such as nightmares and night-terrors. |

Pure bullies had the least physical or psychosomatic health problems. | Bully/victims displayed the highest levels of physical or psychosomatic health problems. | 39–42 |

| Self-harm and suicidality | Those who are bullied were at increased risk for self-harming, suicidal ideation and/or behaviours in adolescence. Moreover, a dose–response relationship was found showing that those who were chronically bullied had a higher risk of suicidal ideation and/or behaviours in adolescence. Lastly, cyberbullying victimisation was not associated with suicidal ideation. | Pure bullies had increased risk of suicidal ideation and suicidal/self-harm behaviour according to child reports of bullying involvement. | Bully/victims were at increased risk for suicidal ideation and suicidal/self-harm behaviour. | 26 43–46 |

| Academic achievement | ||||

| Academic achievement, absenteeism and school adjustment | A significant association was found between peer victimisation, poorer academic functioning and absenteeism only in fifth grade. Frequent victimisation by peers was associated with poor academic functioning (as indicated by grade point averages and achievement test scores) on both a concurrent and a predictive level. Pure victims also showed poor school adjustment and reported a more negative perceived school climate compared to bullies and uninvolved youth. | Pure bullies showed poor school adjustment. | Bully/victims showed poor school adjustment and reported a more negative perceived school climate compared to bullies and uninvolved youth. | 47–49 |

| Social relationships | ||||

| Dating | – | Direct bullying, in sixth grade, predicted the onset of physical dating violence perpetration by eighth grade. | – | 50 |

Childhood to adulthood (18–50 years)

Children who were victims of bullying have been consistently found to be at higher risk for internalising problems, in particular diagnoses of anxiety disorder55 and depression9 in young adulthood and middle adulthood (18–50 years of age) (table 2).56 Furthermore, victims were at increased risk for displaying psychotic experiences at age 188 and having suicidal ideation, attempts and completed suicides.56 Victims were also reported to have poor general health,65 including more bodily pain, headaches and slower recovery from illnesses.57 Moreover, victimised children were found to have lower educational qualifications, be worse at financial management57 and to earn less than their peers even at age 50.56 69 Victims were also reported to have more trouble making or keeping friends and to be less likely to live with a partner and have social support. No association between substance use, anti-social behaviour and victimisation was found. The studies that distinguished between victims and bully/victims showed that usually bully/victims had a slightly higher risk for anxiety, depression, psychotic experiences, suicide attempts and poor general health than pure victims.9 They also had even lower educational qualifications and trouble keeping a job and honouring financial obligations.57 65 In contrast to pure victims, bully/victims were at increased risk for displaying anti-social behaviour and were more likely to become a young parent.62 70 71 Again, we know less about pure bullies, but where studied, they were not found to be at increased risk for any mental or general health problems. Indeed, they were healthier than their peers, emotionally and physically.9 57 However, pure bullies may be more deviant and more likely to be less educated and to be unemployed.65 They have also been reported to be more likely to display anti-social behaviour, and be charged with serious crime, burglary or illegal drug use.58 59 66 However, many of these effects on delinquency may disappear when other adverse family circumstances are controlled for.57

Table 2.

Consequences of involvement in bullying behaviour in childhood/adolescence on outcomes in young adulthood and adulthood (18–50 years)

| Findings | Example References | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Categories | Victims | Bullies | Bully/victims | |

| Health and mental health | ||||

| Anti-social personality disorder | No significant relationship was found between victimisation and anti-social behaviour. | Being a bully increased the risk of violent, property and traffic offences, delinquency, aggressiveness, impulsivity, psychopathy, contact with police or courts and serious criminal charges in young adulthood. | Frequent bully/victim status predicted anti-social personality disorder. Bully/victims also had higher rates of serious criminal charges and broke into homes, businesses and property in young adulthood. | 9 57–61 |

| Anxiety | Victimised adolescents (especially pure victims) displayed a higher prevalence of agoraphobia, generalised anxiety and panic disorder in young adulthood. | No significant relationship was found between being a pure bully and anxiety problems. | Bully/victims displayed higher levels of panic disorder and agoraphobia (females only) in young adulthood. Frequent bully/victim status predicted anxiety disorder. | 55 56 59 62 |

| Depression and internalising problems | All types of frequent victimisation increased the risk of depression and internalising problems. Experiencing more types of victimisation was related to higher risk for depression. On the other hand, Copeland and colleagues did not find a significant association between pure victim status and depression. | No significant association between pure bully status and depression was found. | Bully/victims were at increased risk of young adult depression. | 9 55 56 59 63 |

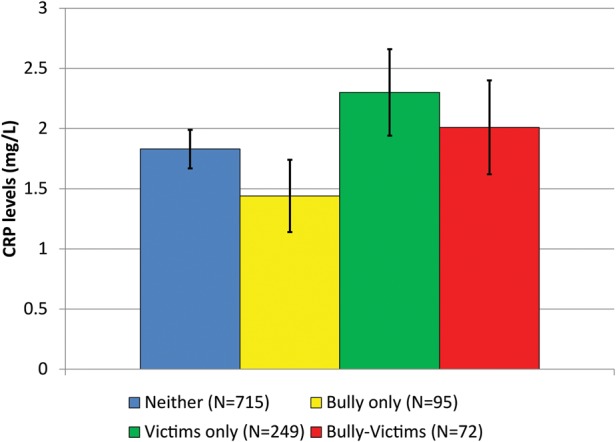

| Inflammation | Being a pure victim in childhood/adolescence predicted higher levels of C-reactive protein (CRP). | Being a pure bully in childhood/adolescence predicted lower levels of CRP. | The CRP level of bully/victims did not differ from that of those uninvolved in bullying. | 64 |

| Psychotic experiences | Pure victims had a higher prevalence of psychotic experiences at age 18 years. | No significant association was found between pure bully status and psychotic experiences. | Bully/victims were at increased risk for psychotic experiences at age 18 years. | 8 |

| Somatic problems | Those who were victimised were more likely to have bodily pain and headache. Frequent victimisation in childhood was associated with poor general health at ages 23 and 50. Moreover, pure victims reported slow recovery from illness in young adulthood. | No significant association was found between health and pure bully status. | Bully/victims were more likely to have poor general health and bodily pain and develop serious illness in young adulthood. They also reported poorer health status and slow recovery from illness. | 56 57 65 |

| Substance use | No significant relationship was found between victimisation and drug use, but being frequently victimised predicted daily heavy smoking. | Bullies were more likely to use illicit drugs and tobacco and to get drunk. | Bully/victim status did not significantly predict substance use but bully/victims were more likely to use tobacco. | 57 59 65 66 |

| Suicidality/self-harm | Results were mixed regarding suicidality and victimisation status. Some showed that all types of frequent victimisation increased the risk of suicidal ideation and attempts. Experiencing many types of victimisation was related to a higher risk for suicidality. However, others only found an association between suicidality and frequent victimisation among girls. | No significant association was found between being a bully and future suicidality. | Male bully/victims were at increased risk for suicidality in young adulthood. | 9 56 67 68 |

| Wealth | ||||

| Academic achievement | Generally, victims had lower educational qualifications and earnings into adulthood. | Bullies were more likely to have lower educational qualifications. | Bully/victims were more likely to have a lower education. | 56 65 69 |

| Employment | Some found no significant association between occupation status and victimisation, whereas others showed that frequent victimisation was associated with poor financial management and trouble with keeping a stable job, being unemployed and earning less than peers. | Bullies were more likely to have trouble keeping a job and honouring financial obligations. They were more likely to be unemployed. | Bully/victims had trouble with keeping a job and honouring financial obligations. | 56 57 |

| Social relationships | ||||

| Peer relationships | Frequently victimised children had trouble making or keeping friends and were less likely to meet up with friends at age 50. | Pure bullies had trouble making or keeping friends. | Bully/victims were at increased risk for not having a best friend and had trouble with making or keeping friends. | 56 57 |

| Partnership | Being a victim of bullying in childhood was not associated with becoming a young parent. Frequent victimisation increased the risk of living without a spouse or partner and receiving less social support at age 50. | When bully/victims were separated from bullies, pure bully status did not have a significant association with becoming a young father (under the age of 22). However, pure bullies were more likely to become young mothers (under the age of 20). No significant association between bully status and cohabitation status was found. | Being a bully/victim in childhood increased the likelihood of becoming a young parent. No significant association between bully/victim and cohabitation status was found. | 65 70 71 |

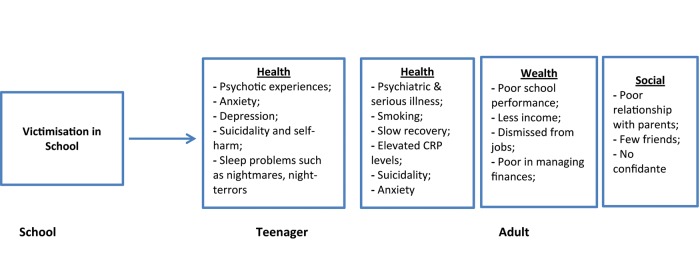

The findings from prospective child, adolescent and adult outcome studies are summarised in figure 1.

Figure 1.

The impact of being bullied on functioning in teenagers and adulthood.

The carefully controlled prospective studies reviewed here provide a converging picture of the long-term effects of being bullied in childhood. First, the effects of being bullied extend beyond the consequences of other childhood adversity and adult abuse.9 In fact, when compared to the experience of having been placed into care in childhood, the effects of frequent bullying were as detrimental 40 years later56! Second, there is a dose–effect relationship between being victimised by peers and outcomes in adolescence and adulthood. Those who were bullied more frequently,56 more severely (ie, directly and indirectly)31 or more chronically (ie, over a longer period of time8) have worse outcomes. Third, even those who stopped being bullied during school age showed some lingering effects on their health, self-worth and quality of life years later compared to those never bullied72 but significantly less than those who remained victims for years (chronic victims). Fourth, where victims and bully/victims have been considered separately, bully/victims seem to show the poorest outcomes concerning mental health, economic adaptation, social relationships and early parenthood.8 9 62 70 Lastly, studies that distinguished between bullies and bully/victims found few adverse effects of being a pure bully on adult outcomes. This is consistent with a view that bullies are highly sophisticated social manipulators who are callous and show little empathy.73

Processes

There are a variety of potential routes by which being victimised may affect later life outcomes. Being bullied may alter physiological responses to stress,74 interact with a genetic vulnerability such as variation in the serotonin transporter (5-HTT) gene,75 or affect telomere length (ageing) or the epigenome.76 Altered HPA-axis activity and altered cortisol responses may increase the risk for developing mental health problems77 and also increase susceptibility to illness by interfering with immune responses.78 In contrast, bullying may also differentially affect normal chronic inflammation and associated health problems that can persist into adulthood.64 Chronically raised C-reactive protein (CRP) levels, a marker of low-grade systemic inflammation in the body, increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases, metabolic disorders and mental health problems such as depression.79 Blood tests revealed that CRP levels in the blood of bullied children increased with the number of times they were bullied. Additional blood tests carried out on the children after they had reached 19 and 21 years of age revealed that those who were bullied as children had CRP levels more than twice as high as bullies, while bullies had CRP levels lower than those who were neither bullies nor victims (figure 2). Thus, bullying others appears to have a protective effect consistent with studies showing lower inflammation for individuals with higher socioeconomic status80 and studies with non-human primates showing health benefits for those higher in the social hierarchy.81 The clear implication of these findings is that both ends of the continuum of social status in peer relationships are important for inflammation levels and health status.

Figure 2.

Adjusted mean young adult C-reactive protein (CRP) levels (mg/L) based on childhood/adolescent bullying status. These values are adjusted for baseline CRP levels as well as other CRP-related covariates. All analyses used robust SEs to account for repeated observations (reproduced from Copeland et al64).

Furthermore, experiences of threat by peers may alter cognitive responses to threatening situations.82 Both altered stress responses and altered social cognition (eg, being hypervigilant to hostile cues38) and neurocircuitry83 related to bullying exposure may affect social relationships with parents, friends and co-workers. Finally, victimisation, in particular of bully/victims, affects schooling and has been found to be associated with school absenteeism. In the UK alone, over 16 000 young people aged 11–15 are estimated to be absent from state school with bullying as the main reason, and 78 000 are absent where bullying is one of the reasons given for absence.84 The risk of failure to complete high school or college in chronic victims or bully/victims increases the risk of poorer income and job performance.57

Summary and implications

Childhood bullying has serious effects on health, resulting in substantial costs for individuals, their families and society at large. In the USA, it has been estimated that preventing high school bullying results in lifetime cost benefits of over $1.4 million per individual.85 In the UK alone, over 16 000 young people aged 11–15 are estimated to be absent from state school with bullying as the main reason, and 78 000 are absent where bullying is one of the reasons given for absence.86 Many bullied children suffer in silence, and are reluctant to tell their parents or teachers about their experiences, for fear of reprisals or because of shame.87 Up to 50% of children say they would rarely, or never, tell their parents, while between 35% and 60% would not tell their teacher.11

Considering this evidence of the ill effects of being bullied and the fact that children will have spent much more time with their peers than their parents by the time they reach 18 years of age, it is more than surprising that childhood bullying is not at the forefront as a major public health concern.88 Children are hardly ever asked about their peer relationships by health professionals. This may be because health professionals are poorly educated about bullying and find it difficult to raise the subject or deal with it.89 However, it is important considering that many children abstain from school due to bullying and related health problems and being bullied throws a long shadow over their lives. To prevent violence against the self (eg, self-harm) and reduce mental and somatic health problems, it is imperative for health practitioners to address bullying.

Footnotes

Contributors: DW conceived the review, produced the first draft and revised it critically; STL contributed to the literature research and writing, and critically reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding: This review was partly supported by the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) grant ES/K003593/1.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Olweus D. Bullying at school: What we know and what we can do. Wiley-Blackwell, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bjorkqvist K, Lagerspetz KM, Kaukiainen A. Do girls manipulate and boys fight? Developmental trends in regard to direct and indirect aggression. Aggress Behav 1992;18:117–27. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wolke D, Woods S, Bloomfield L, et al. The association between direct and relational bullying and behaviour problems among primary school children. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2000;41:989–1002. 10.1111/1469-7610.00687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crick NR, Grotpeter JK. Children's treatment by peers: Victims of relational and overt aggression. Dev Psychopathol 1996;8:367–80. 10.1017/S0954579400007148 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Haynie DL, Nansel T, Eitel P, et al. Bullies, victims, and bully/victims: Distinct groups of at-risk youth. J Early Adolesc 2001;21:29–49. 10.1177/0272431601021001002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boulton MJ, Smith PK. Bully/victim problems in middle-school children: Stability, self-perceived competence, peer perceptions and peer acceptance. Br J Dev Psychol 1994;12:315–29. 10.1111/j.2044-835X.1994.tb00637.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization. Risk behaviours: being bullied and bullying others. In: Currie C, Zanotti C, Morgan A, et al., eds. Social determinants of health and well-being among young people. Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study: International report from the 2009/2010 survey. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe, 2012:191–200. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wolke D, Lereya ST, Fisher HL, et al. Bullying in elementary school and psychotic experiences at 18 years: a longitudinal, population-based cohort study. Psychol Med 2014;44:2199–211. 10.1017/S0033291713002912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Copeland WE, Wolke D, Angold A, et al. Adult psychiatric outcomes of bullying and being bullied by peers in childhood and adolescence. JAMA Psychiatry 2013;70:419–26. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olweus D. Cyberbullying: An overrated phenomenon? Eur J Dev Psychol 2012;9:520–38. 10.1080/17405629.2012.682358 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Radford L, Corral S, Bradley C, et al. The prevalence and impact of child maltreatment and other types of victimization in the UK: Findings from a population survey of caregivers, children and young people and young adults. Child Abuse Negl 2013;37:801–13. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tippett N, Wolke D, Platt L. Ethnicity and bullying involvement in a national UK youth sample. J Adolesc 2013;36:639–49. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wolke D, Woods S, Stanford K, et al. Bullying and victimization of primary school children in England and Germany: Prevalence and school factors. Br J Psychol 2001;92:673–96. 10.1348/000712601162419 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olthof T, Goossens FA, Vermande MM, et al. Bullying as strategic behavior: Relations with desired and acquired dominance in the peer group. J Sch Psychol 2011;49:339–59. 10.1016/j.jsp.2011.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Volk AA, Camilleri JA, Dane AV, et al. Is adolescent bullying an evolutionary adaptation? Aggress Behav 2012;38:222–38. 10.1002/ab.21418 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hawley PH, Little TD, Card NA. The myth of the alpha male: a new look at dominance-related beliefs and behaviors among adolescent males and females. Int J Behav Dev 2008;32:76–88. 10.1177/0165025407084054 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woods S, Wolke D, Novicki S, et al. Emotion recognition abilities and empathy of victims of bullying. Child Abuse Negl 2009;33:307–11. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tippett N, Wolke D. Socioeconomic status and bullying: a meta-analysis. Am J Public Health 2014;104:e48–e59. 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301960 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Camodeca M, Goossens FA, Schuengel C, et al. Links between social informative processing in middle childhood and involvement in bullying. Aggress Behav 2003;29:116–27. 10.1002/ab.10043 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wolke D, Skew A. Family factors, bullying victimisation and wellbeing in adolescents. Longit Life Course Stud 2012;3:101–19. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garandeau C, Lee I, Salmivalli C. Inequality matters: classroom status hierarchy and adolescents’ bullying. J Youth Adolesc 2014;43:1123–33. 10.1007/s10964-013-0040-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wolke D, Skew AJ. Bullying among siblings. Int J Adolesc Med Health 2012;24:17–25. 10.1515/ijamh.2012.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elgar FJ, Craig W, Boyce W, et al. Income inequality and school bullying: multilevel study of adolescents in 37 countries. J Adolesc Health 2009;45:351–9. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ahn HJ, Garandeau CF, Rodkin PC. Effects of classroom embeddedness and density on the social status of aggressive and victimized children. J Early Adolesc 2010;30:76–101. 10.1177/0272431609350922 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schafer M, Korn S, Brodbeck FC, et al. Bullying roles in changing contexts: the stability of victim and bully roles from primary to secondary school. Int J Behav Dev 2005;29:323–35. 10.1177/01650250544000107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Barker ED, Arseneault L, Brendgen M, et al. Joint development of bullying and victimization in adolescence: relations to delinquency and self-harm. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2008;47:1030–8. 10.1097/CHI.ObO13e31817eec98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wichstrøm L, Belsky J, Berg-Nielsen TS. Preschool predictors of childhood anxiety disorders: a prospective community study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2013;54:1327–36. 10.1111/jcpp.12116 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Siegel R, La Greca A, Harrison H. Peer victimization and social anxiety in adolescents: prospective and reciprocal relationships. J Youth Adolesc 2009;38:1096–109. 10.1007/s10964-009-9392-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Storch EA, Masia-Warner C, Crisp H, et al. Peer victimization and social anxiety in adolescence: a prospective study. Aggress Behav 2005;31:437–52. 10.1002/ab.20093 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wolke D, Schreier A, Zanarini MC, et al. Bullied by peers in childhood and borderline personality symptoms at 11 years of age: a prospective study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry 2012;53:846–55. 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2012.02542.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zwierzynska K, Wolke D, Lereya TS. Peer victimization in childhood and internalizing problems in adolescence: a prospective longitudinal study. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2013;41:309–23. 10.1007/s10802-012-9678-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Arseneault L, Milne BJ, Taylor A, et al. Being bullied as an environmentally mediated contributing factor to children's internalizing problems: a study of twins discordant for victimization. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2008;162:145–50. 10.1001/archpediatrics.2007.53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kaltiala-Heino R, Fröjd S, Marttunen M. Involvement in bullying and depression in a 2-year follow-up in middle adolescence. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2010;19:45–55. 10.1007/s00787-009-0039-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kumpulainen K, Rasanen E. Children involved in bullying at elementary school age: their psychiatric symptoms and deviance in adolescence. An epidemiological sample. Child Abuse Negl 2000;24:1567–77. 10.1016/S0145-2134(00)00210-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sweeting H, Young R, West P, et al. Peer victimization and depression in early–mid adolescence: a longitudinal study. Br J Educ Psychol 2006;76:577–94. 10.1348/000709905X49890 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reijntjes A, Kamphuis JH, Prinzie P, et al. Peer victimization and internalizing problems in children: a meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Child Abuse Negl 2010;34:244–52. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.07.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schreier A, Wolke D, Thomas K, et al. Prospective study of peer victimization in childhood and psychotic symptoms in a nonclinical population at age 12 years. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2009;66:527–36. 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.van Dam DS, van der Ven E, Velthorst E, et al. Childhood bullying and the association with psychosis in non-clinical and clinical samples: a review and meta-analysis. Psychol Med 2012;42:2463–74. 10.1017/S0033291712000360 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gini G, Pozzoli T. Association between bullying and psychosomatic problems: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2009;123:1059–65. 10.1542/peds.2008-1215 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wolke D, Lereya ST. Bullying and parasomnias: a longitudinal cohort study. Pediatrics 2014;134:e1040–8. 10.1542/peds.2014-1295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wolke D, Woods S, Bloomfield L, et al. Bullying involvement in primary school and common health problems. Arch Dis Child 2001;85:197–201. 10.1136/adc.85.3.197 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gini G, Pozzoli T. Bullied children and psychosomatic problems: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics 2013;132:720–9. 10.1542/peds.2013-0614 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lereya ST, Winsper C, Heron J, et al. Being bullied during childhood and the prospective pathways to self-harm in late adolescence. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2013;52:608–18.e2. 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Fisher HL, Moffitt TE, Houts RM, et al. Bullying victimisation and risk of self harm in early adolescence: longitudinal cohort study. BMJ 2012;344:e2683 10.1136/bmj.e2683 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Winsper C, Lereya T, Zanarini M, et al. Involvement in bullying and suicide-related behavior at 11 years: a prospective birth cohort study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2012;51:271–82.e3. 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bannink R, Broeren S, van de Looij-Jansen PM, et al. Cyber and traditional bullying victimization as a risk factor for mental health problems and suicidal ideation in adolescents. PLoS One 2014;9:e94026 10.1371/journal.pone.0094026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Nakamoto J, Schwartz D. Is peer victimization associated with academic achievement? A meta-analytic review. Soc Dev 2010;19:221–42. 10.1111/j.1467-9507.2009.00539.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Schwartz D, Gorman AH, Nakamoto J, et al. Victimization in the peer group and children's academic functioning. J Educ Psychol 2005;79:425–35. 10.1037/0022-0663.97.3.425 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Vaillancourt T, Brittain H, McDougall P, et al. Longitudinal links between childhood peer victimization, internalizing and externalizing problems, and academic functioning: developmental cascades. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2013;41:1203–15. 10.1007/s10802-013-9781-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Foshee VA, McNaughton Reyes HL, Vivolo-Kantor AM, et al. Bullying as a longitudinal predictor of adolescent dating violence. J Adolesc Health 55:439–44. 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2014.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vaillancourt T, McDougall P. The link between childhood exposure to violence and academic achievement: complex pathways. J Abnorm Child Psychol 2013;41:1177–8. 10.1007/s10802-013-9803-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Arseneault L, Bowes L, Shakoor S. Bullying victimization in youths and mental health problems: “Much ado about nothing”? Psychol Med 2010;40:717–29. 10.1017/S0033291709991383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Juvonen J, Graham S, Schuster MA. Bullying among young adolescents: the strong, the weak, and the troubled. Pediatrics 2003;112:1231–7. 10.1542/peds.112.6.1231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ttofi MM, Farrington DP, Lösel F, et al. The predictive efficiency of school bullying versus later offending: A systematic/meta-analytic review of longitudinal studies. Crim Behav Ment Health 2011;21:80–9. 10.1002/cbm.808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Stapinski LA, Bowes L, Wolke D, et al. Peer victimization during adolescence and risk for anxiety disorders in adulthood: a prospective cohort study. Depress Anxiety 2014;31:574–82. 10.1002/da.22270 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Takizawa R, Maughan B, Arseneault L. Adult health outcomes of childhood bullying victimization: evidence from a five-decade longitudinal British birth cohort. Am J Psychiatry 2014;171:777–84. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13101401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wolke D, Copeland WE, Angold A, et al. Impact of bullying in childhood on adult health, wealth, crime, and social outcomes. Psychol Sci 2013;24:1958–70. 10.1177/0956797613481608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sourander A, Brunstein Klomek A, Kumpulainen K, et al. Bullying at age eight and criminality in adulthood: findings from the Finnish Nationwide 1981 Birth Cohort Study. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2011;46:1211–19. 10.1007/s00127-010-0292-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Bender D, Losel F. Bullying at school as a predictor of delinquency, violence and other anti-social behaviour in adulthood. Crim Behav Ment Health 2011;21:99–106. 10.1002/cbm.799 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Renda J, Vassallo S, Edwards B. Bullying in early adolescence and its association with anti-social behaviour, criminality and violence 6 and 10 years later. Crim Behav Ment Health 2011;21:117–27. 10.1002/cbm.805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Sourander A, Jensen P, Ronning JA, et al. Childhood bullies and victims and their risk of criminality in late adolescence: the Finnish From a Boy to a Man Study. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med 2007;161:546–52. 10.1001/archpedi.161.6.546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sourander A, Jensen P, Ronning JA, et al. What is the early adulthood outcome of boys who bully or are bullied in childhood? The Finnish “From a Boy to a Man” study. Pediatrics 2007;120:397–404. 10.1542/peds.2006-2704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Brunstein-Klomek A, Sourander A, Kumpulainen K, et al. Childhood bullying as a risk for later depression and suicidal ideation among Finnish males. J Affect Disord 2008;109:47–55. 10.1016/j.jad.2007.12.226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Copeland WE, Wolke D, Lereya ST, et al. Childhood bullying involvement predicts low-grade systemic inflammation into adulthood. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2014;111:7570–5. 10.1073/pnas.1323641111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Sigurdson JF, Wallander J, Sund AM. Is involvement in school bullying associated with general health and psychosocial adjustment outcomes in adulthood? Child Abuse Negl 2014;38:1607–17. 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.06.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Niemelä S, Brunstein-Klomek A, Sillanmäki L, et al. Childhood bullying behaviors at age eight and substance use at age 18 among males. A nationwide prospective study. Addict Behav 2011;36:256–60. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2010.10.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Brunstein Klomek A, Sourander A, Gould MS. The association of suicide and bullying in childhood to young adulthood: a review of cross-sectional and longitudinal research findings. Can J Psychiatry 2010;55:282–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Brunstein-Klomek A, Sourander A, Niemelä S, et al. Childhood bullying behaviors as a risk for suicide attempts and completed suicides: A population-based birth cohort study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2009;48:254–61. 10.1097/CHI.0b013e318196b91f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Brown S, Taylor K. Bullying, education and earnings: evidence from the National Child Development Study. Econ Educ Rev 2008;27:387–401. 10.1016/j.econedurev.2007.03.003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Lehti V, Klomek AB, Tamminen T, et al. Childhood bullying and becoming a young father in a national cohort of Finnish boys. Scand J Psychol 2012;53:461–6. 10.1111/j.1467-9450.2012.00971.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lehti V, Sourander A, Klomek A, et al. Childhood bullying as a predictor for becoming a teenage mother in Finland. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2011;20:49–55. 10.1007/s00787-010-0147-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bogart LM, Elliott MN, Klein DJ, et al. Peer victimization in fifth grade and health in tenth grade. Pediatrics 2014;133:440–7. 10.1542/peds.2013-3510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sutton J, Smith PK, Swettenham J. Social cognition and bullying: Social inadequacy or skilled manipulation? Br J Dev Psychol 1999;17:435–50. 10.1348/026151099165384 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Ouellet-Morin I, Danese A, Bowes L, et al. A discordant monozygotic twin design shows blunted cortisol reactivity among bullied children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2011;50:574–82.e3. 10.1016/j.jaac.2011.02.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sugden K, Arseneault L, Harrington H, et al. Serotonin transporter gene moderates the development of emotional problems among children following bullying victimization. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry 2010;49:830–40. 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.01.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Shalev I, Moffitt TE, Sugden K, et al. Exposure to violence during childhood is associated with telomere erosion from 5 to 10 years of age: a longitudinal study. Mol Psychiatry 2012;18:576–81. 10.1038/mp.2012.32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Harkness KL, Stewart JG, Wynne-Edwards KE. Cortisol reactivity to social stress in adolescents: role of depression severity and child maltreatment. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2011;36:173–81. 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2010.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Segerstrom SC, Miller GE. Psychological stress and the human immune system: a meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry. Psychol Bull 2004;30: 601–30. 10.1037/0033-2909.130.4.601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kaptoge S, Di Angelantonio E, Lowe G, et al. ; Emerging Risk Factors Collaboration. C-reactive protein concentration and risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and mortality: an individual participant meta-analysis. Lancet 2010;375: 132–40. 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61717-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Jousilahti P, Salomaa V, Rasi V, et al. Association of markers of systemic inflammation, C reactive protein, serum amyloid A, and fibrinogen, with socioeconomic status. J Epidemiol Community Health 2003;57:730–3. 10.1136/jech.57.9.730 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sapolsky RM. The influence of social hierarchy on primate health. Science 2005;308:648–52. 10.1126/science.1106477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Mezulis AH, Abramson LY, Hyde JS, et al. Is There a universal positivity bias in attributions? A meta-analytic review of individual, developmental, and cultural differences in the self-serving attributional bias. Psychol Bull 2004;130:711–47. 10.1037/0033-2909.130.5.711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Teicher MH, Samson JA, Sheu YS, et al. Hurtful words: association of exposure to peer verbal abuse with elevated psychiatric symptom scores and corpus callosum abnormalities. Am J Psychiatry 2010;167:1464–71. 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.10010030 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Brown V, Clery E, Ferguson C. Estimating the prevalence of young people absent from school due to bullying. Nat Centre Soc Res 2011;1:1–61. [Google Scholar]

- 85.Masiello M, Schroeder D, Barto S, et al. The cost benefit: a first-time analysis of savings. Highmark Foundation, 2012:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 86.Brown V, Clery E, Ferguson C. Estimating the prevalence of young people absent from school due to bullying. National Centre for Social Research; http://redballoonlearnercouk/includes/files/resources/261298927_red-balloon-natcen-research-reportpdfBrown, 2011:1–61. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Chamberlain T, George N, Golden S, et al. Tellus4 national report: National Foundation for Educational Research. The Department for Children, Schools and Families, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Scrabstein JC, Merrick J. Bullying is everywhere: an expanding scope of public health concerns. Int J Adolesc Med Health 2012;24:1 10.1515/ijamh.2012.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Dale J, Russell R, Wolke D. Intervening in primary care against childhood bullying: an increasingly pressing public health need. J R Soc Med 2014;107:219–23. 10.1177/0141076814525071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]