Abstract

Background

There is mounting evidence that experience of care is a crucial part of the pathway for successful management of long-term conditions.

Design and objectives

To carry out (1) a systematic mapping of qualitative evidence to inform selection of studies for the second stage of the review; and (2) a narrative synthesis addressing the question, What makes for a ‘good’ or a ‘bad’ paediatric diabetes service from the viewpoint of children, young people, carers and clinicians?

Results

The initial mapping identified 38 papers. From these, the findings of 20 diabetes-focused papers on the views on care of ≥650 children, parents and clinicians were synthesised. Only five studies included children under 11 years. Children and young people across all age groups valued positive, non-judgemental and relationship-based care that engaged with their social, as well as physical, health. Parents valued provision responsive to the circumstances of family life and coordinated across services. Clinicians wanting to engage with families beyond a child's immediate physical health described finding this hard to achieve in practice.

Limitations

Socioeconomic status and ethnicity were poorly reported in the included studies.

Conclusions

In dealing with diabetes, and engaging with social health in a way valued by children, parents and clinicians, not only structural change, such as more time for consultation, but new skills for reworking relations in the consultation may be required.

Keywords: Paediatric Practice, Diabetes, Adolescent Health, Health services research, Qualitative research

What is already known on this topic?

Experience of care is a crucial part of pathways to successful management of long-term conditions.

There are ethical, practical, financial and methodological reasons for building on what is already known from published research rather than generating new primary studies.

Although there have been positive exceptions over the last decade, the synthesis of qualitative work in child health research remains underdeveloped.

What this study adds?

Synthesis of the views of at least 650 children, parents and clinicians shows both convergence and tensions within and across groups’ priorities for paediatric long-term care.

Findings indicate that processes of care, as much as disease management, can be problematic for children, young people and their families and clinicians.

Children and young people's preferences for highly individualised, collaborative, relationship-based, care are difficult to achieve.

Introduction

The progressive shift in the involvement of patients, users and citizens from the periphery of practice to a more central position has been mirrored in research and dedicated research funding.1 That said ‘involvement work’ is frequently tokenistic. Methodological and quality development has not always progressed in a stepwise manner with many small studies of ‘user views’. These may have a particular value for localised services, but there are ethical, practical, financial and methodological reasons for building on what is already known from published research rather than generating further small-scale primary studies. This has been well-recognised in trials on the quantitative side, with increased use of meta-analyses and systematic reviews to build an evidence base. Although there have been positive exceptions, over the last decade2–4 the synthesis of qualitative work in child health research has remained underdeveloped. The 2012 report of England's Chief Medical Officer suggests that children's diabetes services may underappreciate the evidence that the pathogenesis of complications starts from the time of diagnosis.5 Data indicate that only 5.8% of all children and young people with diabetes receive the care needed to reduce risk of complications,6 and English outcomes appear poor when compared internationally.7 While the evidence on ‘good’ and ‘poor’ experiences by patients, carers and staff is only one part of the picture in addressing poor outcomes, there is mounting evidence that these experiences are a crucial part of pathways to successful management of long-term conditions.

Methods

This study entailed a secondary analysis of qualitative data—a cost-effective and time-efficient way to access a wider sample than one could reach in a primary study. Our search terms were designed to identify studies relevant to the English health service. These data enable us to understand from the point of view of key actors on what factors enable treatment and social health to ‘work’ (or get in the way of it working). A rapid review—one with restrictions on breadth to support timely findings—was carried out.8 The size of the body of literature required a focused approach with a targeted search.8 Within this scope, the review was carried out in a transparent and systematic way as described in the following sections.

Systematic assessment of evidence

A systematic evidence assessment is one that maps the range and depth of available evidence on a given question, which can then inform the selection of studies for subsequent synthesis.9 The first stage of our review comprised systematic assessment of evidence on views and experiences of paediatric healthcare across chronic illnesses on the basis of the question, What makes for a ‘good’ or a ‘bad’ paediatric chronic illness healthcare service from the viewpoint of children, young people, carers and clinicians? A preliminary sample of 350 citations from scoping searches was discussed by the qualitative review team to inform inclusion criteria for the mapping (see table 1).

Table 1.

Eligibility for the systematic evidence mapping of long-term care studies in paediatrics

| Criteria | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Inclusion criteria | |

|

Focus—views/experiences of service provision for children, young people or young adults (CYP) with long-term conditions; these may include multidisciplinary configurations of services, eg inclusive education; mental healthcare for CYP whose primary condition is not mental health; care by staff outside clinical settings; views on ‘non-adherance’ Participants—children, young people or young adults (authors’ definition) with a long-term condition, their carers, clinicians or support staff who work with children with long-term conditions Design—primary or secondary studies collecting qualitative data and using qualitative methods for analysis* Date—published 2004 onwards Country—carried out in England or Wales (author institutions used as proxy if not directly reported). We kept on file otherwise eligible work from elsewhere in UK and Europe |

Date of publication—since long-term care in England and Wales has changed considerably over time, we considered the past 10 years to be an appropriate cut-off in terms of health technologies, systems for delivery and policy interests Country—studies carried out in England or Wales Differences in the organisation of healthcare and the wider social context, across Europe and North America (and increasingly other parts of the UK) mean that comparative work within the UK and more broadly may be an important area for a more extensive piece of work |

| Exclusion criteria | |

|

Practical grounds of volume control in a rapid review |

*For a discussion of the characteristics of qualitative approaches, see Spencer et al.10

A focused approach to database searching is required in a rapid review.8 Ovid Medline, Ovid Nursing Fulltext Plus and Social Policy and Practice (incorporating ChildData) were selected as likely to offer optimum coverage of both clinical and social science literature. Free-text search strings using synonyms for ‘child’, ‘views’ and ‘long-term care’ were developed and piloted. The final search strings are set out in online supplementary appendix 1.

The publications pages of selected children's voluntary sector websites were hand-searched, along with the reference lists of key clinical and policy guidelines (see online supplementary appendix 2).

Electronic records were screened on title and abstract, and those remaining after application of inclusion and exclusion criteria were screened on full text. Where eligibility was unclear, records were discussed with other members of the team to reach agreement.

Narrative synthesis

The evidence mapping was discussed within the review team and with colleagues working in this field to inform a decision on eligibility and sources for the second stage of the review. It was agreed there was sufficient evidence to support a diabetes-specific focus, with additional material systematically identified from papers kept on file from the evidence mapping, and hand-searching reference lists of eligible studies (see table 2).

Table 2.

Eligibility criteria for synthesis by source

| Criteria | Rationale for inclusion |

|---|---|

| Papers from systematic mapping | |

|

There was sufficient evidence to support a diabetes-specific focus matching the related primary study. Reviews were excluded from the synthesis in order to avoid synthesising first-order and second-order data (primary studies from eligible reviews were included) |

| Additional material | |

|

Papers from reviews in systematic mapping: resolves difficulties around synthesising first-order and second-order data |

| Scottish papers kept on file from mapping: a useful resource for future comparisons between different parts of UK | |

| Papers without abstracts kept on file from systematic mapping: as Paediatric Diabetes does not use abstracts, it was important to include papers without abstracts in the synthesis | |

| Hand-searches of reference lists of studies included in the synthesis: standard practice | |

Papers were quality assessed.2 Data were synthesised using a narrative approach, in which methods of analysis are brought to bear to explore homogeneity and heterogeneity across studies descriptively, rather than statistically.11 Processes of the synthesis are set out in table 3.

Table 3.

Processes of narrative synthesis

| Preliminary synthesis |

|

| Exploration of relationships within and between studies |

|

| Exploration of robustness |

|

Results

The initial evidence mapping identified 38 papers reporting 36 studies (see online supplementary appendix 3 for flow chart). Study methods and data extracted on children's, parents’ and staff views of long-term care are tabulated in online supplementary appendix 4. Also, 5 papers with no abstract and 35 European and Scottish papers were retained on file (see online supplementary appendix 5).

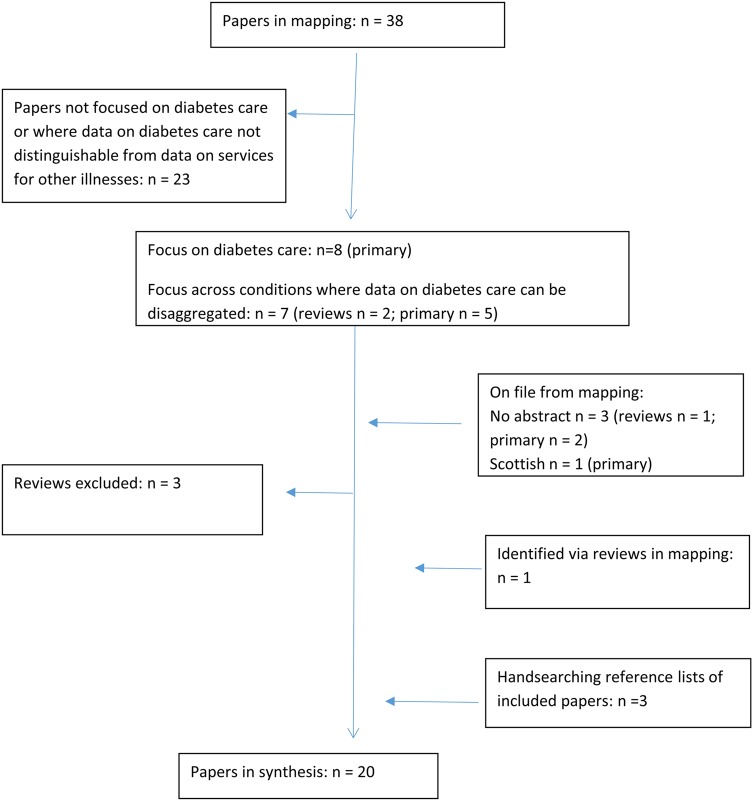

After application of synthesis eligibility criteria, and systematic identification of additional diabetes-related papers (see figure 1), 20 papers describing 18 studies were included in the synthesis. Methods and data extracted from each are set out in online supplementary appendix 6. All items were sufficiently strong to merit inclusion in the synthesis. Study authors reported recruiting via health providers or related voluntary agencies. Several reported recruitment difficulties12–14 and one reported little success in attempts to involve those less likely to use services.15

Figure 1.

Flow chart of selection of studies for synthesis.

A summary of papers by focus and participant group is set out in table 4. Most had a sole diabetes focus (n=16); five also included other conditions. While most papers reported on the experiences of children and young people with type 1 diabetes, in five the diabetes type was not clear (table 4).

Table 4.

Papers in synthesis by focus and participants

| Focus | Studies (papers in the same row report the same study) | Participants n ≥650 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP | Family members/carers | Professionals | |||||

| Diabetes studies | Mixed condition studies (minimum number of CYP with diabetes)* | Diabetes studies | Mixed condition studies (minimum carers with CYP with diabetes) * | Diabetes studies | Mixed condition studies (minimum professionals with responsibility for diabetes)* | ||

| Information, education and support resources | Eiser et al16 | 27 | 18 | 13 | |||

| Waller et al17 Knowles et al18 | 24 | 29 | |||||

| Waller et al19 | 48 | 48 | |||||

| Christie et al20† | 64 mostly mothers | ||||||

| Hummelinck and Pollock 21‡ | 27 (3) | ||||||

| Kirk et al15ठ| 18 (2) | 31 (6) mostly mothers | 36 (6) | ||||

| Williams et al12§ | 46 (16) | 52 (1) | 11 (1) | ||||

| Transition | Allen et al13 14 | 46 | 39 mothers | 38 | |||

| Price et al22 | 11 | ||||||

| Price et al23 | 9 | ||||||

| Coping in school | Boden et al24 | 5 | |||||

| Marshall et al25 | 47 | ||||||

| Newbould et al 26ठ| 69 (26) | 69 (26) | |||||

| Smith et al 27ठ| 27 (2) | 27 (2) | |||||

| General | Dovey-Pearce et al28‡ | 19 | |||||

| Greene29‡ | 5 | ||||||

| Curtis-Tyler30§ | 17 | ||||||

| Brierley et al31 | 14 | ||||||

| Home management from diagnosis | Lowes et al32 | 38 | |||||

| Total participants | 197 | (46) | 236 | (38) | 126 | (7) | |

*Figures show minimum possible totals for children, young people or young adults (CYP) with diabetes where sample size was reported by source of recruitment only27 15; for CYP generally where sample size was reported by method of data collection only;12 27 and for carers where the number of parents participating in each family was not described.19 26 27

†Includes type 2 diabetes.

‡Participants’ diabetes type unclear.

§Includes children under 11 years.

Children and young people

The synthesis drew on the views of 197 children and young people with diabetes across 8 studies (10 papers) with a sole condition focus, and at least 46 (possibly more) with diabetes from 4 studies with a mixed condition focus (table 4). While children and young people with diabetes were the most frequently consulted group, two studies with relatively large samples of parents and no children means that overall more parents than children are included in the synthesis (table 4).

Children and young people's accounts indicate an overriding concern with minimising the threat of the illness and regimen to their social health by protecting their ‘sameness’ to non-diabetic peers (table 5).i 12 15 17 26–30 This may be why ‘extra’ provision (eg, support groups or training courses) (table 5) received a relatively lukewarm response from young people.14 15 17 20 28 It may also underpin the difficulties some authors report with study recruitment.12–14 Children and young people sought highly individualised and collaborative care, which was generally felt to be forthcoming only in the context of ongoing, personal relationships with specific clinicians who know them well (table 5).14 16 22 28 29

Table 5.

Children's, young people's and parents’ priorities for care*

| ‘Bad’ care | ‘Good’ care |

|---|---|

| Children's and young people's concern with maintaining social health | |

| “[Re-injecting at school]: I wouldn't want everyone else looking at me like I've got half a face or something.” (Boy with diabetes, 12 years, Waller et al,17 p.286) “The wish for secrecy had resulted in some people refusing to take medicines [at school].” (Smith et al,27 p.541)” My daughter feels that having diabetes does not mean she has to hang out with others who also have diabetes.” (Christie et al,20 p.391) “… whereas carers viewed formal education favourably, young people were less enthusiastic.” (Allen et al,14 p.144) |

“Think about it. [Intensive therapy] could make us as normal as a normal person without diabetes.” (Boy, 12 years, Waller et al,17 p.286) “She doesn't like being questioned a lot… especially about her diabetes…” (Parent, young person, Smith et al,27 p.541) “I went to Iceland on a school trip but it was fine… My form tutor… was fine with it. For some children he looked after the medication but he let me look after mine.” (Young person, Smith, et al27 p. 542)* |

| Children and young people want clinicians who know them well | |

| “I think what's really stressful is that a lot of people don't see the same health professionals each time… it makes you not want to go [to clinic because] it doesn't really matter if you go or not because if you see a new doctor you can't use his advice because he doesn't know what to advise you about, because he doesn't know you.” (Greene,29 p.53) “She said you should do this and that and she was reading from a text book [but] it's in a text book and it might not exactly apply to me. I might do all that and end up coming into hospital.” (Dovey-Pearce et al,28 p.409) “Sometimes the endocrinologists lose track of the practical side… they say ok, put some more insulin in your body, without even bothering to ask why they're high.” (Greene,29 p.54) |

“[CYP and parents wanted] an ongoing therapeutic relationship… in which HCPs understand the fabric of individuals’ lives.” (Allen et al,14 p.143) “You have to get to know the patient on a personal level before you can kind of tailor advice for them.” (Price et al,22 p.858)” … go and speak to the nurse, get to know them, build up a relationship with them. You know, like practical things you can use in your life.” (Greene,29 p.56)” [Children and young people and parents want] any episodes of deterioration in control … understood in the context of the individual's care trajectory rather than as non-compliance.” (Allen et al,14 p.143) |

| Children and young people's strong preferences about clinicians’ style of interaction | |

| “You're talking to humans.. people, and people kind of forget that.” (Price et al,22 p.858) “I have this one doctor that kept telling me that it was my fault…that's stayed with me, the guilt… you feel like giving up.” (Greene,29 p.54) “Going to the doctor is a bit like going for a test. You either pass or fail and you're relieved when it's over…” (Greene,29 p.54) “[The doctor] used to talk to me like I was a baby [and] to my mum as though I wasn't there.” (Dovey-Pearce et al,28 p.414) “[At home] children saw themselves as active, reliable contributors to care alongside mothers… in clinic [they] felt peripheral.” (Curtis-Tyler,30 p.1306–7) |

“… I was going to stop going altogether to appointments… and I enjoyed going after meeting him ‘cos of the way he treat us.” (Price et al,22 p.859) “I think you need positive reinforcement that you can carry on doing what you need to do.” (Greene,29 p.52) “You need to be offered the opportunity to learn about the process, the trial and error…” (Greene,29 p.52) “Clinicians give different impressions. With some you feel they don't really want you to be there and with others they really want to know about you.” (Greene,29 p.54) “I only had him for a few appointments but he's so down to earth and treated us like an adult.” (Price et al, 22 p.859) |

| Children and young people want opportunities to set the agenda and have choices | |

|

“Some clinicians are happy hearing about the… more human side of life. Others behave like the godfather of medical things. Its more abstract and its harder to speak about your situation.” (Greene,29 p.54) “[Doctors are] often more focussed on your doses or how many times you test your blood sugars, and that's not really what I come for.” (Greene,29 p.54) “[Young people] did not understand why there was an emphasis on HbA1c at the expense of issues of concern to them such as how to integrate self-care into their daily lives.” (Eiser et al,16 p.225) |

“Young people wanted staff to be less abstract when giving information and take into account their individual lifestyle.” (Eiser et al,16 p.225) “You need to be offered the opportunity to learn … how you cope with sports, relationships, exams, family problems which the speciality doesn't always understand.” (Greene,29 p.52) “I came in with a very high HbA1c. I knew it was bad. She [clinician] knew it was bad. She said, OK so that's not so good, so why do you think it's so high? And what do you want to do to start changing it? instead of like my old doctor, who might say something general like you need to eat less’… she asked, where to do you think the best place to start because you can't do it all at once. She let me pick my target for what I thought I could do, which was higher than the clinic recommended… She was reassuring because she said, Well that's good, because it's a lot lower than you have now.” (Greene,29 p.52) “Those that promoted a sense of partnership and collaboration in the consultation were most highly regarded, while those that tended to be based around a ‘set agenda’ were not… while the physical environment and other elements did matter these results suggests the centrality of personal interactions.” (Price et al,22 p.857–8) “I thought the paediatric consultants were brilliant at talking to him… ‘it's up to you’ and then look at him.” (Mother of 12-year-old boy with diabetes, Williams et al,12 p.160) |

| Mothers and fathers valued service responsiveness and coordination of care | |

| “It was me who pushed for [young person] to go … on four injections and they weren‘t happy when I … I pushed and pushed and pushed for it”. (Mother of 9-year-old boy, Williams et al,12 p.157) “There is a clear need to develop service structures that recognise the continuing role played by mothers in the diabetes care of young adults.” (Allen et al,13 p.994) |

“You were there when we needed you… you came round when we needed you… you were at the end of the phone at the end of the day. If I was worried I could pick the phone up. So. I was afraid of feeling very isolated, but no, I haven't felt isolated at all. Quite the reverse actually. There has been somebody there if I've needed them.” (Mother 7, daughter 9 years with diabetes, first interview; Lowes,32 p.534) “I had a word with the school nurse and the dose has been changed. She's stopped taking it at school now.” (Parent, young person with diabetes, Smith et al,27 p.541) “[One] young child (9 years) read the Tadpole Times (Diabetes UK) and found out that he could have multiple doses of insulin and he decided to negotiate with the Doctor for a change of regime: ‘He‘s sort of told Dr [C] and Dr [C] was like oh okay (laughs) fine yeah and so it was a decision he made.” (Mother of 10 year old with diabetes—father also has diabetes; Williams et al,12 p.148) |

*Quotations are selected to illustrate the range of issues raised. See online supplementary appendix 6 for all data extracted across studies. Italicised quotations are direct speech quoted in the study, and roman text is reported by the study author.

Children and young people assessed the quality of their relationships with professionals in terms of the style and content of interaction; they sought positive exchanges in which clinicians demonstrated confidence in their capacities and character, and where there were opportunities to make choices and set the agenda for discussion (table 5).12 14 16 22 28 29

Authors highlighted the role of targeted information and education, for example, in mitigating anxiety at transition14 and helping young people to learn the intricacies of intensive therapy16–19 or to make choices ‘fully appreciating the complexities of one's disease’ (p.151).12 While young people also valued timely provision of practical, tailored resources,12 13 15–17 22 28 29 they suggested this is not always easy to achieve, and likely to be an adjunct to, not a replacement for, the individualised advice from relationships with clinicians who know them well.14 22 28 29

A minority of studies included the views of children under 11 years (n=5). Like teenagers, they described wanting to be ‘normal’ in relation to peers as a priority. At odds with their sense of being a key player in their care at home, they could feel sidelined both in clinic and when trying to look after their diabetes at school.12 15 26 27 30 Though authors’ interest in transition from paediatric to adult services13 14 22 23 may account for the focus on teenagers in the majority of studies retrieved, it chimes with these reports of a tendency for views of younger children to be excluded at clinic level.12 30 Authors of studies with younger children describe their ‘extraordinary maturity and adaptability’, expertise in their care arising out of their day-to-day experiences of living with illness and their willingness to discuss this when approached by an adult demonstrating confidence in their capabilities and character (ref. 12, p.153, ref. 30).

Mothers, fathers, carers and families

At least 236 family members were consulted across six diabetes studies, and at least 38 more across mixed condition studies, again mainly about information, education and additional support resources (table 4). Unsurprisingly, a central theme was the need to protect children's immediate safety—and, where possible, minimise the impact of care on daily life.15 17–19 21 26 27 32

Perhaps as a function of studies in which they were invited to participate, parents focused on how provision supported or inhibited achieving these ends, for example, in schools, during transition or via timely information/education.12–15 17 18 20 21 26 27 32 Like children and young people they valued ‘uninterrupted relationships’,13 14 but as one part of a wider concern with responsiveness of, and coordination across services as a whole (table 5). As described above, children and young people's views on care in schools tended to focus on threats to their social well-being as much as physical health;12 15 17 26–30 whereas nurses flagged hypoglycaemia and the absence of a statutory framework on teachers’ responsibilities.24 25 In terms of transition, feedback across groups pointed to the need for approaches that ‘more closely match the reality of families’ lives and changing interdependencies’, accommodating differences across and within families.12–14

Clinicians

Authors provided information on the backgrounds of about half of the 133 professionals involved with diabetes provision: most were nurses; support staff were not reported to have been consulted (see online supplementary appendix 6). Clinicians reported a range of aims for care.12 16 23 31 For some, “quality of life [was] paramount”;31 elsewhere “the absolute importance of achieving satisfactory glycaemic control as the goal against which current and future health and behaviour are measured”.23 31

Authors of included studies described clinicians as differing in their understandings of the proper scope and style for consultation. Some “focused on the medical aspects of diabetes and the need for discipline, with much less emphasis on the social and interpersonal consequences”31 while others aimed to understand “the wants and needs of the individual”31 and “appreciate where they are coming from”.23

Clinicians reported awareness of their need for continuity. The diabetes team in one study agreed to appoint ‘key workers’ for young people across their transition clinics.31 However, they feared the education needs of early career colleagues might compromise this;14 31 and that ‘workload and time pressure’ could lead to them falling “back on relating to an individual in terms of their social and cultural background, education or motivation…” (ref. 31, p.679)—not the individualised approach they aspired to and young people sought.

In practice, a holistic approach could be viewed as a distraction from, rather than part of, the effort “to find ways of um improving… control”;23 “we're too busy looking at… HbA1cs”.23 Some felt that they lacked the skills for holistic engagement, especially when this involved topics such as drug/alcohol use and sexual health, not “subjects I would naturally tend to discuss”, “it feels a bit uncomfortable”.23 Arguably, the preponderance of papers on ‘extra’ education or ‘support’ interventions (table 4) may indicate a preference for engaging with the non-biomedical outside the consultation room. Most consultations in Williams and colleagues’ observation work focused on ‘adherence to treatment rather than exploring causes of non-compliance’.12 Unresolved professional differences about the aims of care and inconsistent styles of engagement were a source of confusion and dissatisfaction for young people.16 31

Discussion

Drawing on the views of ≥650 children, parents and clinicians, this qualitative literature synthesis found that children and young people of all ages value positive, relationship-based approaches that engage with their social, as well as physical, health. Children, young people and parents valued care that was as sensitive to the wider context of their lives as to their bodies. Parents wanted responsive provision, particularly across services and specialities. Unsurprisingly, they wanted children to be safe, but also had concerns for their social health. Clinicians, sometimes less attuned to families’ priorities beyond physical health, were inclined to see ‘non-adherence’ in terms of a need for education. They were divided between those who espoused a focus on medical outcomes alone and those who wanted to engage with children and families’ wider priorities but felt that this was squeezed out in day-to-day practice. Quite apart from their concern for children's well-being, healthcare professionals need their patients to do well so that their clinic performs well and is seen to do so. But a focus on medical outcomes alone does not engage with the extent to which, in the context of chronic illness, processes of care as much as disease management are problematic.

The main limitation of our study is the trade-off between a timeliness and confidence of no study missed, mitigated by transparent methods and data. There was poor reporting in included studies of socioeconomic status, ethnicity and comorbidity—all factors that affect the ‘how’ as well as the ‘what’ in service delivery. While recruiting those less engaged with services can be challenging,33 with a few exceptions,13 15 papers include little discussion of these biases. This means we may have failed to capture the views of those at greatest risk and with most to tell us. Finally, all authors of included studies were from healthcare organisations or were health science academics, so the focus of papers (eg, on educational interventions) may be influenced by (and may themselves influence) current concerns in clinical settings. Strengths of the paper include a cost-effective and relatively speedy study in an area where there is policy commitment to change; researchers sharing research tasks for reliability, comparing notes and discussing within a team of social scientists and clinicians. The appendices provide a resource for those researching this area.

Conclusion

Implementation may require not only structural change, such as more time for consultation, but new skills for reworking relations in a context where children know their physiological outcomes are necessarily judged.30 Clinicians may need skills in negotiating children's and parents’ sometimes differing priorities for care, and ensuring pressing parental concerns about children's physical health do not squeeze out opportunities for children to contribute.34 Since holistic care opens up a much larger part of children and families’ lives to professional scrutiny,30 relationship building will be increasingly important in a National Health Service with patients at the centre, and with social and physical health informing interaction between healthcare professionals and the family.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the members of the Policy Research Unit for the Health of Children, Young people and Families: Catherine Law, Ruth Gilbert, Russell Viner, Miranda Wolpert, Amanda Edwards, Steve Morris and Cathy Street. We are also grateful to Linda Haines.

Footnotes

Contributors: HR, TS and Linda Haines framed the original research question, which was further developed by KCT and LA. KC-T developed electronic search strings, carried out searches and synthesis, and drafted methods and findings. LA carried out policy document searches and primary, exploratory data synthesis. All contributed to the development of eligibility criteria, worked on drafts of the paper and approved the final version of this article.

Funding: This work was supported by the Policy Research Unit in the Health of Children, Young People and Families, which is funded by the Department of Health Policy Research Programme, grant number: PR-UN-0409-10016. This is an independent report commissioned and funded by the Department of Health. The views expressed are not necessarily those of the Department.

Competing interests: None.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

We use the phrase ‘social health’ rather than ‘well-being’ or ‘psychosocial health’ to reflect young people's reported views that discussions of the social impact of their care should not be split off from their regular encounters with the doctors and nurses into additional ‘support’ or psychological provision, crucial though these may be for some.

References

- 1.Bedford Russell AR, Passant M, Kitt H. Engaging children and parents in service design and delivery. Arch Dis Child 2014;99:1158–62 10.1136/archdischild-2013-304869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas J, Sutcliffe K, Harden A, et al. Children and healthy eating: a systematic review of barriers and facilitators. London: SSRU, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Morris C, Janssens A, Allard A, et al. Informing the NHS Outcomes Framework: evaluating meaningful health outcomes for children with neurodisability using multiple methods including systematic review, qualitative research, Delphi survey and consensus meeting. Health Serv Deliv Res 2014;2 ISSN: 2050-4349. 10.3310/hsdr02150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Attree P. Growing up in disadvantage: a systematic review of the qualitative evidence. Child Care Health Dev 2004;30:679–89. 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2004.00480.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davies SC. Annual Report of the Chief Medical Officer 2012, Our Children Deserve Better: Prevention Pays. London: DH, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Paediatric Diabetes Audit Project Board. National Paediatric Diabetes Audit 2010–11 2012.

- 7.NHS Diabetes. National Paediatric Diabetes Service Improvement Delivery Plan 2013–2018 2013.

- 8.Petticrew M, Roberts H. Systematic reviews in the social sciences: a practical guide. Oxford: Blackwell; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Caird J, Hinds K, Kwan I, et al. (2012) A systematic rapid evidence assessment of late diagnosis. London: EPPI Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Spencer L, Ritchie J, Lewis J, et al. Quality in Qualitative evaluation: a framework for assessing research evidence. London: Cabinet Office, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arai L, Britten N, Popay J, et al. Testing methodological developments in the conduct of narrative synthesis: a demonstration review of research on the implementation of smoke alarm interventions. Evid Policy J Res Debate Pract 2007;3:361–83. 10.1332/174426407781738029 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Williams A, Noyes J, Chandler-Oatts J, et al. Children's Health Information Matters: Researching the practice of and requirements for age appropriate health information for children and young people. Final Report 2011.

- 13.Allen D, Channon S, Lowes L, et al. Behind the scenes: the changing roles of parents in the transition from child to adult diabetes service. Diabetic Med 2011;28:994–1000. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2011.03310.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Allen D, Cohen D, Hood K, et al. Continuity of care in the transition from child to adult diabetes services: a realistic evaluation study. J Health Serv Res Policy 2012;17:140–8. 10.1258/jhsrp.2011.011044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kirk S, Beatty S, Callery P, et al. Perceptions of effective self-care support for children and young people with long-term conditions. J Clin Nurs 2012;21:1974–87. 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.04027.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Eiser C, Johnson B, Brierley S, et al. Using the Medical Research Council framework to develop a complex intervention to improve delivery of care for young people with Type 1 diabetes. Diabetic Med 2013;30:e223–8. 10.1111/dme.12185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waller H, Eiser C, Heller S, et al. Adolescents’ and their parents’ views on the acceptability and design of a new diabetes education programme: a focus group analysis. Child Care Health Dev 2005;31:283–9. 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2005.00507.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Knowles J, Waller H, Eiser C, et al. The development of an innovative education curriculum for 11–16 yr old children with type 1 diabetes mellitus (T1DM). Pediatr Diabetes 2006;7:322–8. 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2006.00210.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waller H, Eiser C, Knowles J, et al. Pilot study of a novel educational programme for 11–16 year olds with type 1 diabetes mellitus: the KICk-OFF course. Arch Dis Child 2008;93:927–31. 10.1136/adc.2007.132126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Christie D, Romano GM, Thompson R, et al. Attitudes to psychological groups in a paediatric and adolescent diabetes service–implications for service delivery. Pediatr Diabetes 2008;9(4 pt 2):388–92. 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2008.00382.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hummelinck A, Pollock K. Parents’ information needs about the treatment of their chronically ill child: a qualitative study. Patient Educ Couns 2006;62:228–34. 10.1016/j.pec.2005.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Price C, Corbett S, Lewis-Barned N, et al. Implementing a transition pathway in diabetes: a qualitative study of the experiences and suggestions of young people with diabetes. Child Care Health Dev 2011;37:852–60. 10.1111/j.1365-2214.2011.01241.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Price C, Corbett S, Dovey-Pearce G. Barriers and facilitators to implementing a transition pathway for adolescents with diabetes: a health professionals’ perspective. Int J Child Adolesc Health 2010;3:489–98. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Boden S, Lloyd CE, Gosden C, et al. The concerns of school staff in caring for children with diabetes in primary school. Pediatr Diabetes 2012;13:e6–e13. 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2011.00780.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marshall M, Gidman W, Callery P. Supporting the care of children with diabetes in school: a qualitative study of nurses in the UK. Diabetic Med 2013;30:871–7. 10.1111/dme.12154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Newbould J, Francis SA, Smith F. Young people's experiences of managing asthma and diabetes at school. Arch DisChild 2007;92:1077–81. 10.1136/adc.2006.110536 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Smith F, Taylor K, Newbould J, et al. Medicines for chronic illness at school: experiences and concerns of young people and their parents. J Clin Pharm Ther 2008;33:537–44. 10.1111/j.1365-2710.2008.00944.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dovey-Pearce G, Hurrell R, May C, et al. Young adults’(16–25 years) suggestions for providing developmentally appropriate diabetes services: a qualitative study. Health Soc Care Community 2005;13(5):409–19. 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2005.00577.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Greene A. What healthcare professionals can do: a view from young people with diabetes. Pediatr Diabetes 2009;10(Suppl 13):50–7. 10.1111/j.1399-5448.2009.00615.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Curtis-Tyler K. Facilitating children's contributions in clinic? Findings from an in-depth qualitative study with children with Type 1 diabetes. Diabetic Med 2012;29:1303–10. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03714.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brierley S, Eiser C, Johnson B, et al. Working with young adults with Type 1 diabetes: views of a multidisciplinary care team and implications for service delivery. Diabetic Med 2012;29:677–81. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2012.03601.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lowes L, Lyne P, Gregory J. Childhood diabetes: parents’ experience of home management and the first year following diagnosis. Diabetic Med. 2004;21:531–8. 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2004.01193.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lucas PJ, Curtis-Tyler K, Arai L, et al. What works in practice? User and provider perspectives on the acceptability, affordability, implementation, and impact of a family-based intervention for child overweight and obesity delivered at scale. BMC Public Health 2014;14:614 10.1186/1471-2458-14-614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Coyne I. Children's participation in consultations and decision-making at health service level: a review of the literature. Int J Nurs Stud 2008;45:1682–9. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.