A 50-year-old Chinese woman reported a sharp paroxysmal headache and abrupt paralysis of the left leg. She then developed ptosis, blurred vision, diplopia and fever. On admission, a neurological examination revealed right III, IV, VI and left V1 cranial nerve palsy, bilateral upper eyelid oedema and left leg monoplegia (Medical Research Council grade 2/5). In addition, a left Babinski sign and nuchal rigidity were observed. Blood tests revealed elevated white cell count (WCC) and a majority of the cells were neutrophils. Lumbar puncture revealed that the WCC (120×106/μL) and protein level (0.79 g/L) of the cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) were slightly elevated, though the intracranial pressure was normal. A cranial MRI showed an infarction in the right corona radiata and base of the skull structures were also involved. MR arteriography indicated that multiple intracranial large arteries were narrowed Figure 1. Moreover, the CSF culture indicated Streptococcus anginosus infection, which was diagnostically very important. Accordingly, the patient was treated with vancomycin, tinidazole, low-molecular-weight heparin calcium and dexamethasone for 2 weeks. She achieved remission of the neurological symptoms but her heart rate gradually slowed (45–65 bpm) and blood pressure decreased (75–90/45–50 mm Hg). She became depressed and developed apathy towards food. The Mini-Mental State Examination score (23/30) mainly indicated memory deterioration, disorientation and partial acalculia. The results of timely blood pituitary function tests indicated considerably decreased free T3, free T4 and thyroid-stimulating hormone levels, which indicated primary hypothyroidism. After subsequent administration of 12.5 mg/day levothyroxine for 2 months, the patient's heart rate and blood pressure were normalised and mental status returned to normal.

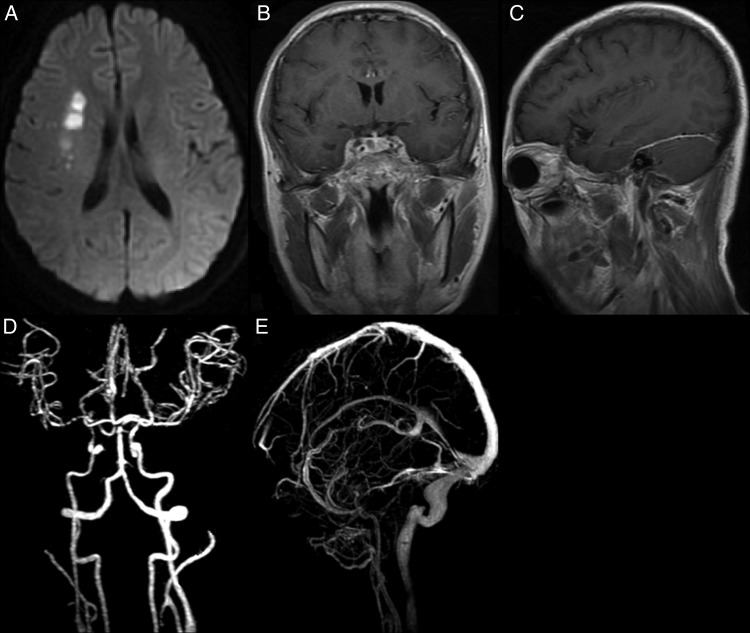

Figure 1.

Brain parenchema, meninges and cerebral vascular angiography studies. (A) Transverse view of diffusion-weighted imaging demonstrates infarction in the right corona radiata. (B and C) MR enhancement showed obvious involvement of the saddle area, pituitary stalk and tentorium of cerebellum. (D and E) MR angiography indicates narrowing of A2 segments of the bilateral anterior cerebral artery, a narrowed M2 segment in the right middle cerebral artery and cavernous segments in the right internal cervical artery; but the venous system was not obviously constricted except for thinness of the left transverse sinus, sigmoid sinus and internal jugular vein.

At this point, a CSF bacterial culture established the specific pathogen to be S. anginosus, a member of the Streptococcus milleri group colonising the human oral cavity, pars pharyngeal pharynges. When a healthy individual's immunity declines, opportunistic infection with S. anginosus may occur.1 2 Apart from causing a toothache and headache, the infection may spread intracranially to cause meningitis and cerebral venous system thrombophlebitis.3 4 In addition, inflammatory involvement of multiple large arteries, that is, the internal carotid artery (ICA) and its branches, the anterior and middle cerebral arteries—is another rare specific feature secondary to S. anginosus infection. Because the cavernous segment of the ICA courses through the cavernous sinus, S. anginosus infection can also extend to enter the ICA and cause diffuse inflammation of the sinus, which in turn causes thrombosis and narrowing of the ICA and its branches. Inflammation may also spread to the carotid sheath through the parapharyngeal space.3 Monoplegia and hemiplegia due to cerebral infarction are possible complications of arterial thrombosis. Considering the inflammatory mechanisms involved in the coagulant system, an early anticoagulation treatment of cerebral infarction is necessary.5 In the present case, the enhancement of the pituitary stalks on MRI and the presentation of primary hypothyroidism indicate partial pituitary insufficiency, which is also rarely reported. Theoretically, the cause might have involved the impairment of the hypothalamus–pituitary–thyroid axis through inflammatory damage to the pituitary stalk. The patient's favourable outcome confirmed the validity of the thyroxine replacement therapy.

We found that the initial CSF WCC that resulted from the S. anginosus intracranial infection, which is similar to those in viral infections, was considerably lower than that in typical acute bacterial meningitis, in which the count could reach thousands per microlitre in CSF. This may be a unique trait of the bacteria that needs to be investigated. Because the bacteria are facultative aerobes, early use of ceftriaxone, meropenem or vancomycin with tinidazole is necessary.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Contributors: All the authors were responsible for the study concept and design; acquired, analysed and interpreted the data; supervised and coordinated the study; and drafted/revised the manuscript for content.

Funding: This work was financially supported by the National Basic Research Program of China (2013CB966900 to F.D.S), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81322018, 81273287 and 81100887 to J.W.H), the Program for New Century Excellent Talents in University of China (NCET 111067 to J.W.H), and the Key Project of Natural Science Foundation of Tianjin Province (12JCZDJC24200 to J.W.H).

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The present study was approved by the ethics committee of Tianjin Medical University General Hospital.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Weightman NC, Barnham MR, Dove M. Streptococcus milleri group bacteraemia in North Yorkshire, England (1989–2000). Indian J Med Res 2004;119:164–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Udaondo P, Garcia-Delpech S, Diaz-Llopis M, et al. Bilateral intraorbital abscesses and cavernous sinus thromboses secondary to Streptococcus milleri with favourable outcome. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg 2008;24:408–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feldman DP, Picerno NA, Porubsky ES. Cavernous sinus thrombosis complicating odontogenic parapharyngeal space neck abscess: a case report and discussion. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2000;123:744–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ebright JR, Pace MT, Niazi AF. Septic thrombosis of the cavernous sinuses. Arch Intern Med 2001;161:2671–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bhatia K, Jones NS. Septic cavernous sinus thrombosis secondary to sinusitis: are anticoagulants indicated? A review of the literature. J Laryngol Otol 2002;116:667–76. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.