Abstract

Objective:

To investigate the effects of chemotherapy and cranial irradiation on normal brain tissue using in vivo neuroimaging in patients with glioblastoma.

Methods:

We used longitudinal MRI to monitor structural brain changes during standard treatment in patients newly diagnosed with glioblastoma. We assessed volumetric and diffusion tensor imaging measures in 14 patients receiving 6 weeks of chemoradiation, followed by up to 6 months of temozolomide chemotherapy alone. We examined changes in whole brain, gray matter (GM), white matter (WM), anterior lateral ventricle, and hippocampal volumes. Normal-appearing GM, WM, and hippocampal analyses were conducted within the hemisphere of lowest/absent tumor burden. We examined diffusion tensor imaging measures within the subventricular zone.

Results:

Whole brain (F = 2.41; p = 0.016) and GM (F = 2.13; p = 0.036) volume decreased during treatment, without significant WM volume change. Anterior lateral ventricle volume increased significantly (F = 65.51; p < 0.001). In participants analyzed beyond 23 weeks, mean ventricular volume increased by 42.2% (SE: 8.8%; t = 4.94; p < 0.005). Apparent diffusion coefficient increased within the subventricular zone (F = 7.028; p < 0.001). No significant changes were identified in hippocampal volume.

Conclusions:

We present evidence of significant and progressive treatment-associated structural brain changes in patients with glioblastoma treated with standard chemoradiation. Future studies using longitudinal neuropsychological evaluation are needed to characterize the functional consequences of these structural changes.

With the increasing success of anticancer therapies, treatment-associated toxicities among survivors have emerged as an important clinical problem, with cognitive deficits detectable in 17% to 75% of patients with cancer after chemotherapy.1–4 Patients with CNS malignancy appear to be at particular risk, given the combined effects of chemotherapy and cranial radiation therapy (RT).5–7

Recent studies have investigated the effects of chemotherapy and radiation on global and regional brain anatomy using voxel-based morphometry (VBM) and diffusion tensor imaging (DTI).8–19 While the design and results of these studies vary, they collectively suggest that CNS toxicity is associated with cancer therapy even for non-CNS malignancies, with widespread gray matter (GM) and white matter (WM) loss, and associated deficits in multiple cognitive domains.15,16 Few studies, however, have examined the extended time course of these effects, and none has assessed longitudinal changes on MRI in patients receiving chemotherapy and cranial RT. Understanding how neurotoxic exposure alters healthy brain tissue will provide context for future investigations into the relationship between brain changes and neurocognitive performance, and whether individual differences in long-term neurologic outcomes may be predicted by neuroimaging.

In the present study, we aimed to explore the time course of treatment-associated neurotoxicity, with particular interest in regions serving endogenous neural repair and brain plasticity. We used VBM and DTI to examine longitudinal anatomical changes in radiographically tumor-free brain tissue in patients with glioblastoma receiving a standard chemoradiation protocol with serial neuroimaging in up to 9 months of treatment.

METHODS

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents.

Data were obtained through a prospective clinical study of patients with glioblastoma conducted at our institution (NCT00756106), as previously described.20 The local institutional review board approved this protocol. All participants provided written informed consent.

Participants and treatment protocol.

The protocol used serial MRI scans in patients receiving standard chemoradiation for glioblastoma after craniotomy for tumor resection. No additional investigational agents were allowed. Participants received temozolomide at a daily oral dose of 75 mg/m2 concurrent with daily RT. RT was administered to the tumor core with a 1- to 2-cm margin in 30 consecutive fractions of 2 Gy daily for a total dose of 60 Gy. One month after completing RT, patients underwent up to 12 cycles of temozolomide at 150 to 200 mg/m2 daily on 5 consecutive days of a 28-day cycle.

Image acquisition.

All MRI and DTI scans were acquired on a 3.0T MRI system (TimTrio; Siemens Medical Solutions, Malvern, PA). Participants were scanned twice before starting chemoradiation (3–7 days before and 1 day before), weekly during chemoradiation, and then monthly for 6 months. The MRI scanning protocol included pre- and postcontrast 1-mm3, T1-weighted multiecho magnetization-prepared rapid-acquisition gradient echo (MEMPRAGE) images, fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) images, and DTI.

Image processing.

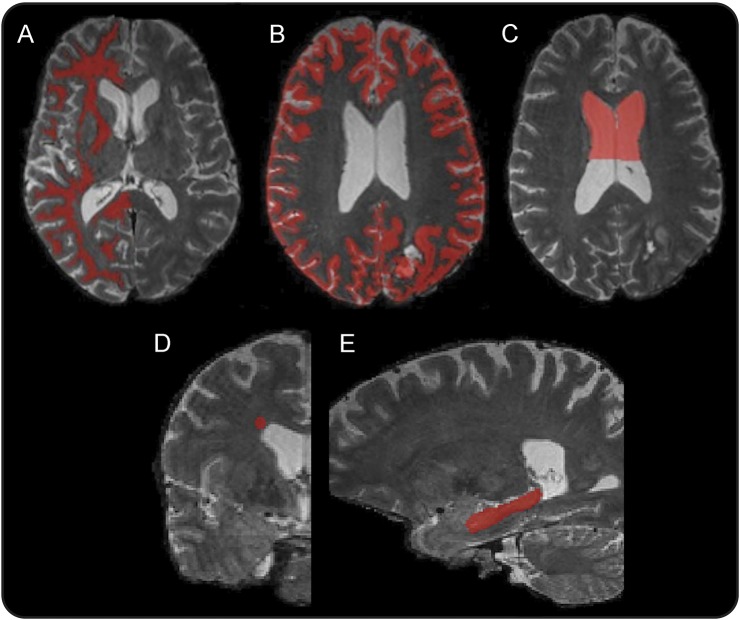

Five regions of interest (ROIs) were outlined on the anatomical MRIs: normal-appearing GM, normal-appearing WM, anterior lateral ventricles, hippocampus, and subventricular zone (SVZ) (figure 1). Volumetric changes in nontumor, normal-appearing brain tissue were assessed in GM, WM, lateral ventricles, and hippocampus. To control for geometric distortions arising from changes in tumor morphology, GM and WM volumetric analyses were restricted to participants in whom tumor burden was confined to one hemisphere, with volumetric data being extracted from the tumor-free contralateral hemisphere. This was performed automatically by finding the midsagittal plane and comparing its position with reference to manually drawn tumor ROIs. We selected participants who had at least 5 sequential imaging time points meeting this condition. MEMPRAGE images were “denoised” using an algorithm based on a nonlocal means method.21 Images were then segmented into WM, GM, and CSF using FMRIB's Software Library (FSL) (www.fmrib.ox.ac.uk/fsl). This was independently performed for each time point.

Figure 1. Regions of interest.

Representative regions of interest for white matter (A), gray matter (B), anterior lateral ventricle volume (C), subventricular zone (D), and hippocampus (E).

Lateral ventricle ROIs were constructed on T1-weighted MEMPRAGE images using semiautomatic tissue segmentation in ITK-SNAP.22 ROIs were drawn on baseline images and nonrigidly coregistered using Advanced Normalization Tools23 to subsequent scans in each patient's imaging series. This process allows ROIs to change with shifts in tissue volumes between time points. Each ROI was visually inspected to ensure quality of coregistration. Ventricular ROIs were restricted to the anterior aspects of the lateral ventricles, given extensive posterior ventricular involvement in the majority of participants that distorted ventricular anatomy and made assessment of exclusively nontumor-related changes inaccurate (one participant was excluded because of excessive periventricular tumor involvement). The posterior margin of these ROIs was drawn at the point of maximum superior convexity of the overlying corpus callosum (figure 1). Hippocampal ROIs were constructed on each participant's baseline MEMPRAGE images using manual tissue segmentation in ITK-SNAP based on a previously published protocol21 and nonrigidly coregistered to subsequent images using Advanced Normalization Tools. ROIs were drawn within the hemisphere of lowest tumor burden. DTI measures were examined in the hemisphere with lowest or no tumor burden. These measures included the apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) and fractional anisotropy (FA). ADC measures the magnitude of water diffusion in tissue and is inversely proportional to the impedance of diffusion by intact cell membranes and myelin. FA is a scalar value between 0 and 1 that indexes the directional uniformity of water diffusion.

WM masks were generated by FSL from MEMPRAGE images at each time point. Since the resulting WM mask included some subcortical GM structures, they were identified and excluded by an atlas-based segmentation using the Harvard-Oxford atlas.24–27 Similarly, voxels occupied by tumor, or edema, were excluded from the WM mask using manually drawn tumor ROIs. For each participant, WM masks of all time points were registered into a common image space and their intersection was generated. The resulting WM mask was then reregistered to T2-weighted images at each time point.

ROI analysis was conducted within the lateral SVZ lining the lateral ventricles. This region was sampled with 5-mm spherical ROIs centered within the WM superolateral to the ventricular wall within the hemisphere of lowest or no tumor burden on each patient's baseline scan (figure 1). These ROIs were placed on the T2 MRI in the coronal plane at the anterior border of the lateral ventricle and nonrigidly coregistered to the subsequent scans in each participant's series. ADC and FA maps were registered into the same T2 space, and values were extracted at each time point.

Data analysis.

Voxel volumes were extracted from denoised GM and WM masks and from coregistered ventricular masks at each time point using MATLAB (The MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA). Percentage change from baseline was plotted over time (figure 2). Longitudinal volume changes were statistically assessed as a function of time (days) since the baseline scan, using linear regression, and including as covariates patient age and sex to control for between-subjects variation, and time-point specific tumor volume on FLAIR to control for within-subjects variability in tumor burden between scanning sessions. Missing time points were included in the model. For participants remaining on the protocol up to or beyond the 12th scanning session (23 weeks from baseline; n = 6), pairwise t tests were conducted to compare ventricular volumes and WM ADC values at baseline and 23 weeks. This time point was chosen to capture sufficient time from baseline while avoiding prohibitive patient attrition at later time points.

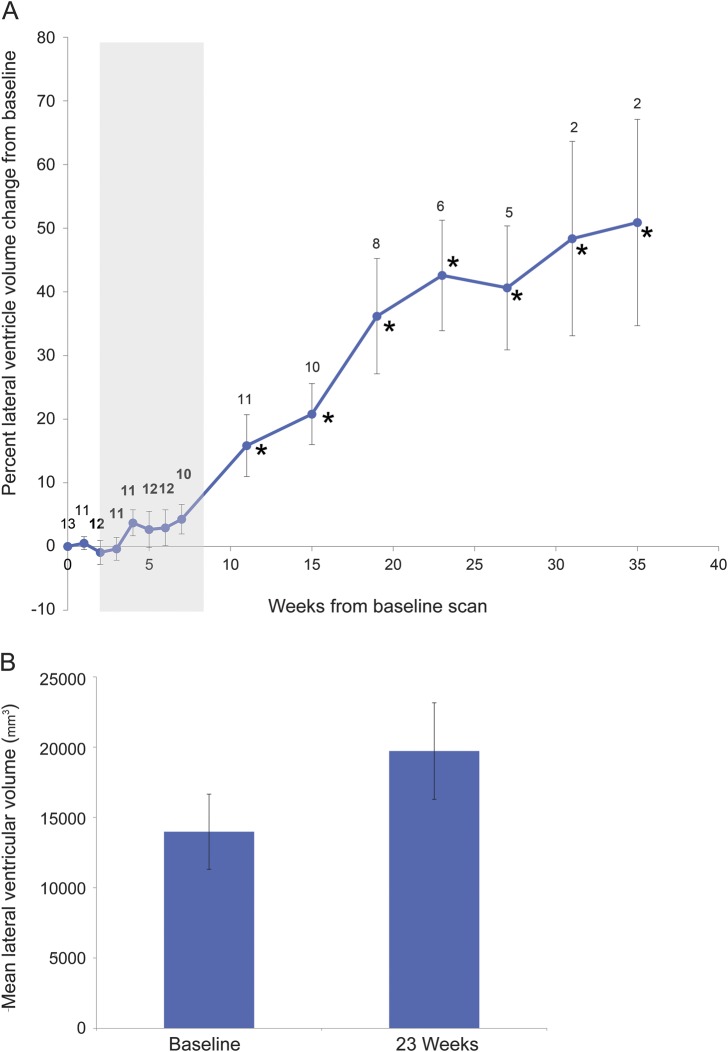

Figure 2. Longitudinal progression of WB (A), GM (B), and WM (C) volumes across the treatment period.

Data points represent the sample mean of percent volume change from baseline at each time point. Error bars represent the SEM. Sample sizes are indicated at each time point. Gray shading indicates combined chemotherapy and radiation. Six participants did not meet criteria for volumetric analysis. *Time points at which volumetric changes are statistically significant (p < 0.05). GM = gray matter; WB = whole brain; WM = white matter.

RESULTS

Patient characteristics.

A total of 14 patients were analyzed (8 female, 6 male; mean age 60 years [range 35–70]; mean Karnofsky performance score 90 [range 60–100]). Following subtotal resection (n = 10) or biopsy (n = 4), all patients completed 6 weeks of chemoradiation. During chemoradiation, 3 patients received no steroids, 7 patients were tapered off or continued on low-dose steroids, and 4 patients required increased steroid dosing. Three participants completed the full 35-week protocol. Attrition among the remaining 11 participants was attributable to patient death, clinical decline, dose-limiting drug toxicities, or enrollment in an alternate therapeutic clinical trial.

VBM of WB, GM, and WM volumes.

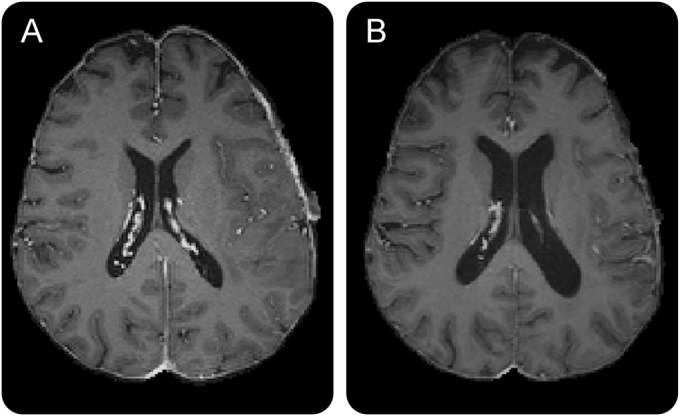

Six participants were excluded from WB, GM, and WM volume analysis because they lacked 5 sequential imaging time points with unilateral tumor burden, a requirement of our automated tissue segmentation protocol. In the remaining 8 participants, sample sizes at each time point were as follows: 8 at weeks 0 through 4, 7 at weeks 5 and 6, 5 at week 7, 8 at week 11, 6 at weeks 15 and 19, 4 at week 23, and 3 at weeks 27, 31, and 35 (figure 2, A–C). WB volume decreased significantly (F = 2.41; p = 0.016; figure 2A) from baseline to last follow-up, independent of age, sex, and tumor volume. Cortical GM volumes also decreased during treatment (F = 2.12; p = 0.036; figure 2B) independent of age, sex, and tumor volume. WM volumes did not change significantly during treatment (F = 0.70; p = 0.49; figure 2C). Representative structural differences before and after treatment are shown in figure 3.

Figure 3. T1 MRI at baseline and 28 weeks.

(A) Pretreatment baseline T1 scan. (B) Posttreatment T1 scan (28 weeks from baseline).

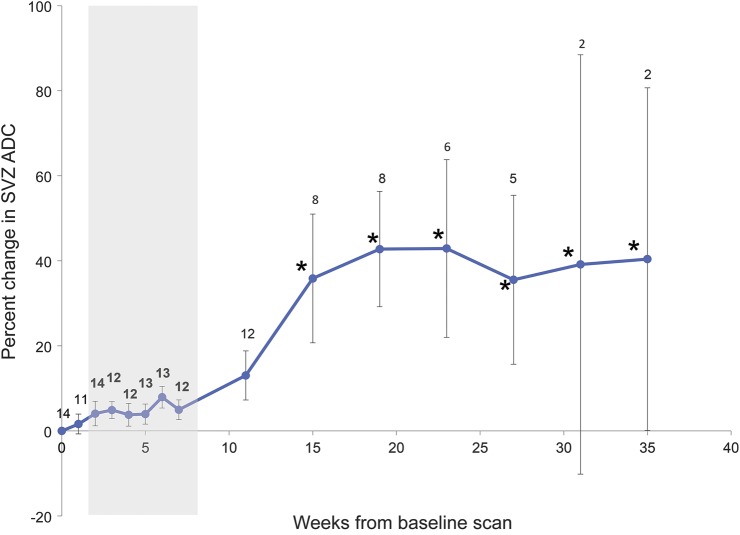

Volumetric analysis of anterior lateral ventricles and hippocampus.

One participant was excluded from ventricular volumetric analysis because of extensive ventricular tumor involvement. Sample sizes at each time point in ventricular volume analysis were as follows: 13 at week 0, 11 at week 1, 12 at week 2, 11 and weeks 3 and 4, 12 at weeks 5 and 6, 10 at week 7, 11 at week 11, 10 at week 15, 8 at week 19, 6 at week 23, 5 at week 27, and 2 at weeks 31 and 35. Significant anterior ventricular volume expansion was evident over time, independent of age, sex, residual tumor volume, or steroid exposure during chemoradiation (F = 15.247; p < 0.001; figure 4A).

Figure 4. Longitudinal progression of anterior lateral ventricular volume.

(A) Lateral ventricular volumes across the treatment period. Data points represent the sample mean of percent volume change from baseline at each time point. Error bars represent the SEM. Sample sizes are indicated at each time point. Gray shading indicates combined chemotherapy and radiation. One participant was excluded because of extensive ventricular tumor involvement. *Time points at which volumetric changes are statistically significant (p < 0.05). (B) Lateral ventricular volumes at baseline and 23 weeks in participants remaining on the protocol to this point (n = 6). Bars represent sample means at baseline and 23 weeks; error bars represent the SEM.

In a subgroup of participants continuing on monthly temozolomide beyond 23 weeks (n = 6), mean anterior lateral ventricle volume increased by 42.2% (SE: 8.8%; t = 4.94; p < 0.005; figure 4B). In addition to these quantitative measures, ventricular dilation was radiographically evident in most participants (see video on the Neurology® Web site at Neurology.org). Hippocampal volumes showed no significant change over time (n = 14; data not shown).

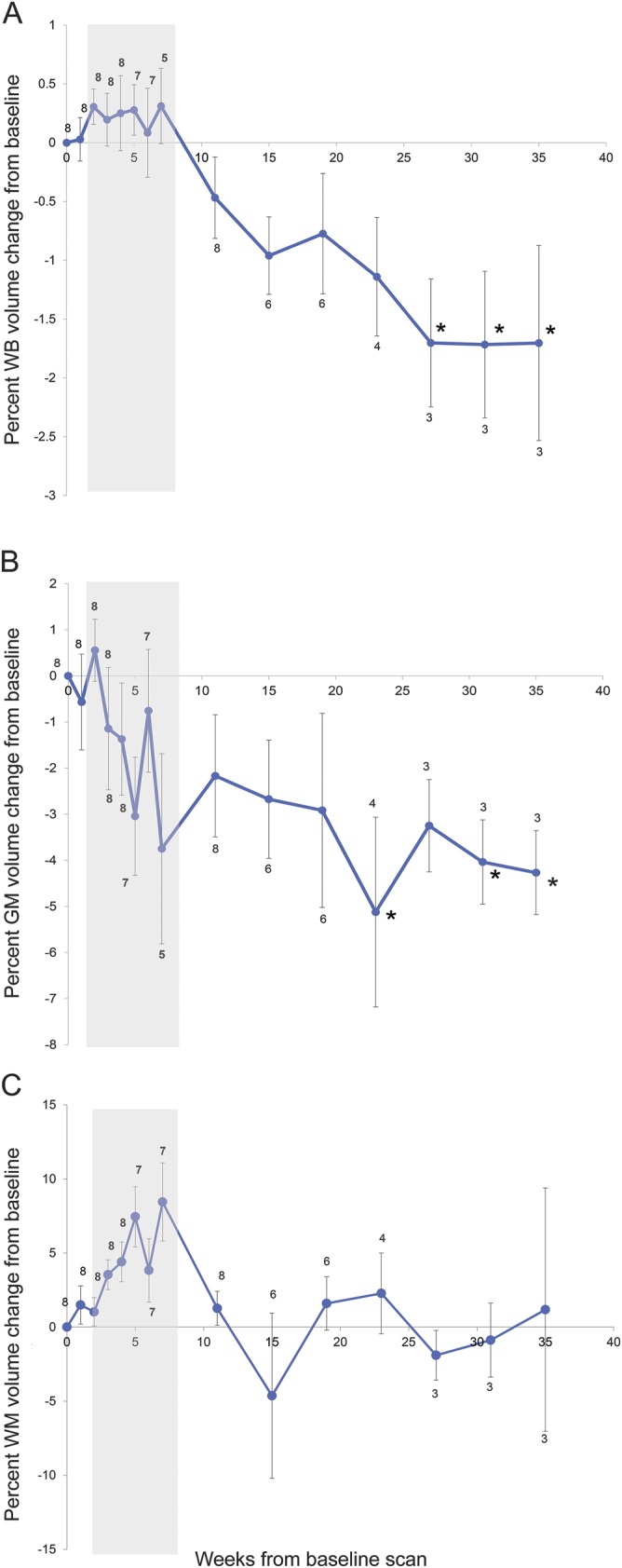

Diffusion tensor imaging.

Within normal-appearing hemispheric WM masks contralateral to greatest tumor burden, no changes were observed in FA or ADC during chemoradiation (data not shown). ADC was measured within the SVZ of each participant, with sample sizes varying between time points as follows: 14 at week 0, 11 at week 1, 14 at week 2, 12 at weeks 3 and 4, 13 at weeks 5 and 6, 12 at weeks 7 and 11, 8 at weeks 15 and 19, 6 at week 23, 5 at week 27, and 2 at weeks 31 and 35. ADC increases were seen within SVZ ROIs, independent of age, sex, and tumor FLAIR volume (F = 7.028; p < 0.001; figure 5). FA values within the lateral SVZ, however, showed no significant change over time (data not shown).

Figure 5. Longitudinal progression of ADC values from SVZ.

ADC values from SVZ region of interest across the treatment period. Data points represent the sample mean of percent volume change from baseline at each time point. Error bars represent the SEM. Sample sizes are indicated at each time point. Gray shading indicates combined chemotherapy and radiation. *Time points at which volumetric changes are statistically significant (p < 0.05). ADC = apparent diffusion coefficient; SVZ = subventricular zone.

DISCUSSION

We present longitudinal MRI-based evidence of tumor-independent structural brain changes in patients with glioblastoma during combined treatment with systemic temozolomide and cranial RT. Progressive brain atrophy was seen through significant losses of GM volume, dilation of lateral ventricles, and loss of WM integrity in the SVZ, with relative sparing of hippocampal volume and parenchymal WM. The use of neuroimaging at multiple time points over several months offers a novel view of the nature, severity, and time course of treatment-associated brain changes in patients with glioma.

Ventricular dilation following chemoradiation has been observed previously on longitudinal CT and MRI studies on chemoradiation for CNS neoplasms.28,29 Of note, in one series,27 longitudinal ventricular enlargement scaled closely with progressive cortical atrophy, consistent with our findings of GM-predominant volume loss. In this way, ventricular dilation appears to be a correlate of GM loss and may prove to be a useful biomarker of longitudinal atrophy in the clinical setting. The association between ventricular dilation and GM loss has been observed in patients with dementia, with progressive ventricular dilation predicting GM loss in cognitively relevant cortical surfaces.30 It is plausible, therefore, that GM atrophy accounts for the observed expansion of CSF space, and that these changes may have consequences for neurocognitive function in patients receiving chemoradiation.

We did not observe significant WM atrophy or DTI changes at the hemisphere level, despite the findings of prior studies that have documented WM volume loss, gliosis, and demyelination in patients undergoing chemoradiation.12,13,28 Focal, rather than whole brain RT may spare parenchymal WM the atrophic changes that have previously been observed. In addition, our limited sample size may also have been insufficiently powered to detect subtle effects on WM. Despite the absence of hemisphere-level WM changes, we did observe significant ADC changes in the SVZ, a dynamic and highly vascular region densely populated with neural progenitor cells (NPCs), which are known to be vulnerable to irradiation31 and multiple chemotherapeutic agents, even at subtherapeutic levels.32,33 While it is impossible to attribute ADC elevation to a specific etiology based on neuroimaging alone, it is possible that injury to the SVZ's dividing cell populations and microvasculature disrupts local diffusion properties.

Brain changes followed a delayed time course, with minimal changes seen within the first 6 weeks of treatment, after which WB and GM volume loss and ventricular dilation appeared to follow a progressive pattern. Our data do not, however, provide conclusive evidence regarding the irreversibility of these changes, as the longest follow-up was 35 weeks. While we did not find evidence of reversibility within this time period, we cannot exclude the possibility that some degree of CNS repair leads to partial or complete reversal of morphometric changes in long-term survivors. Exploration of this question awaits further studies assessing patients longitudinally over years, rather than months.

It is of interest that the onset of significant morphologic changes appears to coincide with the time of RT completion. We are unable, however, to parse the independent effects of RT, chemotherapy, or their combination during the initial 6 weeks of treatment. It has been shown that patients treated with chemoradiation appear to experience greater memory, attention, and executive function deficits compared with those undergoing chemotherapy alone.34 It is possible that radiation represents the predominant driver of these changes, with early exposure initiating a neurodegenerative process that progresses over time. It is also conceivable that progressive brain changes result from the synergistic effects of chemotherapy and radiation, and that ongoing monthly chemotherapy after completion of RT is an important driver of brain atrophy. In addition, novel targeted therapies, such as antiangiogenic agents,7 are entering mainstream clinical practice. Large datasets investigating exposure to antiangiogenic agents20 and separate use of chemotherapy and radiation35 are emerging and will be indispensable to future investigations of neurotoxicity from cancer therapies.

Chemotherapy and radiation appear to injure CNS tissue through independent mechanisms. Many classes of chemotherapeutic agents have been shown to directly target normal brain cells, with self-renewing NPCs and oligodendrocytes among the most vulnerable to neurotoxic insult.31 Preclinical studies suggest that chemotherapy injures CNS tissue through a combination of short- and long-term effects related to depletion of NPCs and glial cells, impaired neurogenesis, and progressive loss of WM integrity.31,32 Like chemotherapy, brain RT is also known to target progenitor cells, increasing apoptosis, decreasing cell proliferation, and accelerating hippocampal cell death.30,36 Suggested mechanisms for long-term RT-induced neurotoxicity include microglia-mediated neuroinflammation and loss of microvascular integrity, with subsequent ischemic damage to neural and glial progenitor cells and WM tracts.6

Our study was limited by the absence of detailed cognitive performance measures to correlate with the observed structural changes on neuroimaging. To correlate neurocognitive outcomes with structural brain changes, longitudinal prospective trials are needed to examine performance in multiple cognitive domains in concert with serial neuroimaging. Such data will help characterize the functional effects of structural brain changes within this population and may also clarify the significance of individual differences in brain volume loss. For example, it is conceivable that rapid, early volume loss might be a sensitive indicator of worse neurocognitive outcome, and prediction models based on such individual differences may help stratify risk of long-term adverse effects.

Although our findings provide strong evidence of structural brain changes that suggest a real neuroanatomical phenotype, our cohort's small size, particularly after participant attrition at later time points, limits the generalizability of our findings. A larger prospective clinical trial will be needed to confirm and validate the reported findings. Definitive confirmation and validation of our findings must await further exploration in larger datasets. It should further be noted that imaging analysis in patients with brain tumor remains challenging. Our analyses were constrained by the presence of a dynamically changing tumor burden with considerable mass effect and visit-to-visit variability in tumor size and surrounding edema. Given our relatively small sample size and the frequency of bilateral tumor burden in our participants, we were unable to restrict many of our analyses to patients with a tumor-free hemisphere. Therefore, we included data from manually drawn ROIs when tumor burden did not appear to involve the structure of interest; however, future studies in patients with brain cancer undergoing combined chemoradiation may preferentially include patients with minimal tumor burden, or who have undergone a gross total tumor resection to further validate the effects of chemoradiation on the normal brain.

As novel therapies have improved cancer survival, the delayed effects of treatment-associated toxicity in survivors represent a particular challenge for oncologists and neurologists seeking to maximize patients' quality of life. Characterizing imaging biomarkers and the natural history of neurologic injury secondary to chemotherapy and radiation is essential not only for optimal clinical management of patients with cancer but also as a foundation for developing and testing neuroprotective strategies.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors thank the patients who participated in this study.

GLOSSARY

- ADC

apparent diffusion coefficient

- DTI

diffusion tensor imaging

- FA

fractional anisotropy

- FLAIR

fluid-attenuated inversion recovery

- FSL

FMRIB's Software Library

- GM

gray matter

- MEMPRAGE

multiecho magnetization-prepared rapid-acquisition gradient echo

- NPC

neural progenitor cell

- ROI

region of interest

- RT

radiation therapy

- SVZ

subventricular zone

- VBM

voxel-based morphometry

- WM

white matter

Footnotes

Supplemental data at Neurology.org

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.D., M.P., and E.G. designed the study. Funding was obtained by T.T.B., E.G., and J.D., M.P., E.G., K.J., J.K., and P.P. were responsible for data collection. All authors contributed to the data analysis and interpretation. M.P. and J.D. wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Substantial reviewing and editing were provided by E.G. and T.T.B., and all authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

STUDY FUNDING

This work was conducted with support from the National Cancer Institute and NIH, R01CA129371 and K24CA125440A (T.T.B.). J.D. is a recipient of the American Academy of Neurology Clinical Research Training Fellowship. This work has also been supported by a K-12 institutional award (to J.D.), the American Cancer Society (to J.D.), internal funds from the Department of Radiology at the Massachusetts General Hospital (to E.G., K.J., J.K., and P.P.), and philanthropic support (to J.D.).

DISCLOSURE

M. Prust, K. Jafari-Khouzani, J. Kalpathy-Cramer, and P. Polaskova report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. T. Batchelor is a consultant or is an advisory board member for Advance Medical, Agenus, Champions Biotechnology, Kirin Pharmaceuticals, Merck & Co., Inc., Novartis, Proximagen, and Roche, and has received research funding from AstraZeneca, Millennium, and Pfizer. E. Gerstner reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. J. Dietrich is a consultant for Monteris Pharmaceuticals. Go to Neurology.org for full disclosures.

REFERENCES

- 1.van Dam FS, Schagen SB, Muller MJ, et al. Impairment of cognitive function in women receiving adjuvant treatment for high-risk breast cancer: high-dose versus standard-dose chemotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst 1998;90:210–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schagen SB, van Dam FS, Muller MJ, Boogerd W, Lindeboom J, Bruning PF. Cognitive deficits after postoperative adjuvant chemotherapy for breast carcinoma. Cancer 1999;85:640–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ahles TA, Saykin AJ, Furstenberg CT, et al. Neuropsychologic impact of standard-dose systemic chemotherapy in long-term survivors of breast cancer and lymphoma. J Clin Oncol 2002;20:485–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wefel JS, Lenzi R, Theriault RL, Davis RN, Meyers CA. The cognitive sequelae of standard-dose adjuvant chemotherapy in women with breast carcinoma: results of a prospective, randomized, longitudinal trial. Cancer 2004;100:2292–2299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Taphoorn MJB, Klein M. Cognitive deficits in adult patients with brain tumours. Lancet Neurol 2004;3:159–168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dietrich J, Monje M, Wefel J, Meyers C. Clinical patterns and biological correlates of cognitive dysfunction associated with cancer therapy. Oncologist 2008;13:1285–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tanaka S, Louis DN, Curry WT, Batchelor TT, Dietrich J. Diagnostic and therapeutic avenues for glioblastoma: no longer a dead end? Nat Rev Clin Oncol 2013;10:14–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Inagaki M, Yoshikawa E, Matsuoka Y, et al. Smaller regional volumes of brain gray and white matter demonstrated in breast cancer survivors exposed to adjuvant chemotherapy. Cancer 2007;109:146–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McDonald BC, Conroy SK, Smith DJ, West JD, Saykin AJ. Frontal gray matter reduction after breast cancer chemotherapy and association with executive symptoms: a replication and extension study. Brain Behav Immun 2013;30(suppl):S117–S125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Ruiter MB, Reneman L, Boogerd W, et al. Late effects of high-dose adjuvant chemotherapy on white and gray matter in breast cancer survivors: converging results from multimodal magnetic resonance imaging. Hum Brain Mapp 2012;33:2971–2983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koppelmans V, de Ruiter MB, van der Lijn F, et al. Global and focal brain volume in long-term breast cancer survivors exposed to adjuvant chemotherapy. Breast Cancer Res Treat 2012;132:1099–1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaiser J, Bledowski C, Dietrich J. Neural correlates of chemotherapy-related cognitive impairment. Cortex 2014;54:33–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Simó M, Rifà-Ros X, Rodriguez-Fornells A, Bruna J. Chemobrain: a systematic review of structural and functional neuroimaging studies. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 2013;37:1311–1321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Abraham J, Haut MW, Moran MT, Filburn S, Lemiuex S, Kuwabara H. Adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer: effects on cerebral white matter seen in diffusion tensor imaging. Clin Breast Cancer 2008;8:88–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deprez S, Amant F, Yigit R, et al. Chemotherapy-induced structural changes in cerebral white matter and its correlation with impaired cognitive functioning in breast cancer patients. Hum Brain Mapp 2011;32:480–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Deprez S, Amant F, Smeets A, et al. Longitudinal assessment of chemotherapy-induced structural changes in cerebral white matter and its correlation with impaired cognitive functioning. J Clin Oncol 2012;30:274–281. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nagesh V, Tsien CI, Chenevert TL, et al. Radiation-induced changes in normal-appearing white matter in patients with cerebral tumors: a diffusion tensor imaging study. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2008;70:1002–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nazem-Zadeh MR, Chapman CH, Lawrence TL, Tsien CI, Cao Y. Radiation therapy effects on white matter fiber tracts of the limbic circuit. Med Phys 2012;39:5603–5613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chapman CH, Nazem-Zadeh M, Lee OE, et al. Regional variation in brain white matter diffusion index changes following chemoradiotherapy: a prospective study using tract-based spatial statistics. PLoS One 2013;8:e57768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Batchelor TT, Gerstner ER, Emblem KE, et al. Improved tumor oxygenation and survival in glioblastoma patients who show increased blood perfusion after cediranib and chemoradiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013;110:19059–19064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jafari-Khouzani K. MRI upsampling using feature-based nonlocal means approach. IEEE Trans Med Imaging 2014;33:1969–1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yushkevich PA, Piven J, Hazlett HC, et al. User-guided 3D active contour segmentation of anatomical structures: significantly improved efficiency and reliability. Neuroimage 2006;31:1116–1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Avants BB, Tustison NJ, Song G, Cook PA, Klein A, Gee JC. A reproducible evaluation of ANTs similarity metric performance in brain image registration. Neuroimage 2011;54:2033–2044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Jafari-Khouzani K, Elisevich KV, Patel S, Soltanian-Zadeh H. Dataset of magnetic resonance images of nonepileptic subjects and temporal lobe epilepsy patients for validation of hippocampal segmentation techniques. Neuroinformatics 2011;9:335–346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frazier JA, Chiu S, Breeze JL, et al. Structural brain magnetic resonance imaging of limbic and thalamic volumes in pediatric bipolar disorder. Am J Psychiatry 2005;162:1256–1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Makris N, Goldstein JM, Kennedy D, et al. Decreased volume of left and total anterior insular lobule in schizophrenia. Schizophr Res 2006;83:155–171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Desikan RS, Ségonne F, Fischl B, et al. An automated labeling system for subdividing the human cerebral cortex on MRI scans into gyral based regions of interest. Neuroimage 2006;31:968–980. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stylopoulos LA, George AE, de Leon MJ, et al. Longitudinal CT study of parenchymal brain changes in glioma survivors. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol 1988;9:517–522. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Omuro AM, Ben-Porat LS, Panageas KS, et al. Delayed neurotoxicity in primary central nervous system lymphoma. Arch Neurol 2005;62:1595–1600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Madsen SK, Gutman BA, Joshi SH, et al. Mapping ventricular expansion onto cortical gray matter in older adults. Neurobiol Aging 2015;36(suppl 1):S32–S41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Monje ML, Mizumatsu S, Fike JR, Palmer TD. Irradiation induces neural precursor-cell dysfunction. Nat Med 2002;8:955–962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dietrich J, Han R, Yang Y, Mayer-Pröschel M, Noble M. CNS progenitor cells and oligodendrocytes are targets of chemotherapeutic agents in vitro and in vivo. J Biol 2006;5:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Han R, Yang YM, Dietrich J, Luebke A, Mayer-Pröschel M, Noble M. Systemic 5-fluorouracil treatment causes a syndrome of delayed myelin destruction in the central nervous system. J Biol 2008;7:12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Correa DD, Shi W, Abrey LE, et al. Cognitive functions in primary CNS lymphoma after single or combined modality regimens. Neuro Oncol 2012;14:101–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wick W, Platten M, Meisner C, et al. Temozolomide chemotherapy alone versus radiotherapy alone for malignant astrocytoma in the elderly: the NOA-08 randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol 2012;13:707–715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Parihar VK, Limoli CL. Cranial irradiation compromises neuronal architecture in the hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013;110:12822–12827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.