Summary

Matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) regulates remodeling of the left ventricle after myocardial infarction (MI) and is tightly linked to the inflammatory response. The inflammatory response serves to recruit leukocytes as part of the wound healing reaction to the MI injury, and infiltrated leukocytes produce cytokines and chemokines that stimulate MMP-9 production and release. In turn, MMP-9 proteolyzes cytokines and chemokines. While in most cases MMP-9 cleavage of the cytokine or chemokine substrate serves to increase activity, there are cases where cleavage results in reduced activity. Global MMP-9 deletion in mouse MI models has proven beneficial, suggesting inhibition of some aspects of MMP-9 activity may be valuable for clinical use. At the same time, overexpression of MMP-9 in macrophages has also proven beneficial, indicating that we still do not fully understand the complexity of MMP-9 mechanisms of action. In this review, we summarize the cycle of MMP-9 effects on cytokine production and cleavage to regulate leukocyte functions. While we use myocardial infarction as the example process, similar events occur in other inflammatory and wound healing conditions.

Keywords: MMP, inflammation, myocardial infarction, cytokines, chemokines, proteomics

1. Introduction

Matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) are zinc-dependent endopeptidases involved in the degradation of the extracellular matrix (ECM). While protease activity is well controlled under normal physiological conditions, during pathological processes such as wound healing following myocardial infarction (MI), MMPs are activated to stimulate ECM turnover.[1] Among the MMPs involved in post-MI remodeling of the left ventricle (LV), MMP-9 is a principal participant. In humans, MMP-9 exists as a 92 kDa pro-form and as 88 and 65 kDa active forms that result from removal of the pro-domain and C-terminal hemopexin-like domain.[2] In mice, MMP-9 exists as a 105 kDa pro-form and 95 kDa active form.[3]

MMP-9 proteolytically processes a wide variety of ECM proteins.[4] In addition, MMP-9 cleaves growth factors and inflammatory mediators. While MMP-9 is secreted by endogenous cardiac cell types (e.g., cardiomyocytes, endothelial cells, and fibroblasts), it is also produced by non-resident cells that infiltrate the infarct in response to ischemic injury (e.g., leukocytes).[5–7] MMP-9 levels increase early post-MI and remain elevated during the first week, mirroring leukocyte infiltration and demonstrating that leukocytes are the primary post-MI MMP-9 source.[8–10]

Cardiomyocyte death due to prolonged ischemia yields infarction and triggers robust cytokine, chemokine, and adhesion molecule upregulation.[11] Leukocytes bring in ECM degradative enzymes (including MMP-9), and ECM degradation enhances leukocyte infiltration by increasing permeability of the cardiac microvasculature, as well as by releasing ECM-bound chemotactic factors and exposing cryptic ECM sites possessing chemotactic properties (matricryptins).[12, 13] Mass spectrometry can be used to map the exact cleavage site(s), which has proven useful for functional assays.

MMP-9, in particular, contributes to post-MI wound granulation, wound contraction, and collagen deposition, the combined actions of which determine scar formation and quality. Scar quality directly contributes to regional and global LV function. Post-MI, MMP-9 deletion protects the LV from rupture and excessive ventricular dilation, and paradoxically facilitates angiogenesis in mice.[14, 15] While a large number of MMP-9 substrates have been catalogued using individual in vitro cleavage assays and global proteomic strategies, which MMP-9 substrates are most applicable in the post-MI LV and which substrates within a complex mixture are preferred by MMP-9 are still not fully understood.[16, 17]

Regulation of the post-MI myocardial inflammatory response is pivotal.[18] Studies in animal models (both MMP-9 deletion and overexpression mouse models) have demonstrated that MMP-9 modulates a multitude of cytokines and chemokines, including those listed in Table 1.[19, 20] While in the majority of cases, MMP-9 processing of cytokines and chemokines generates more active species, there are cases where MMP-9 cleavage served to shut off the activity. We examined the current literature to provide a comprehensive review. This review focuses on the role of MMP-9 in regulating the inflammatory response post-MI and in being regulated by the inflammatory response, highlighting the effect of cytokines and chemokines on MMP-9 production by inflammatory cells and MMP-9 regulation of cytokine and chemokine function through proteolytic processing.

Table 1.

Summary of inflammatory substrates proteolytically processed by matrix metalloproteinase-9 in the setting of myocardial infarction. [21, 22, 32–36, 38, 39, 42–45, 66] For IL-8, where it is cleaved determines effect.

| Substrate | Cleavage Effect | MI-Relevant Cellular Souces |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Mediators | ||

| CXCL1 (GRO-α) | ↓ activity | neutrophil, macrophage, endothelial cells, myocytes, fibroblasts |

| CXCL4 (PF4) | ↓ activity | neutrophil, macrophage, fibroblast |

| CXCL5 (ENA-78) | ↑ activity | neutrophil, endothelial cells, fibroblasts |

| CXCL6 (GCP-2) | ↑ activity | macrophages, fibroblast, endothelial cells |

| CXCL9 (MIG) | ↓ activity | macrophage, fibroblast, endothelial |

| CXCL10 (IP10) | ↓ activity | macrophage, fibroblast, myocytes |

| CXCL11 (I-TAC) | ↓ activity | neutrophil, macrophage, endothelial cells |

| CXCL12 (SDF-1) | ↓ activity | neutrophil, macrophage |

| IL-1β | Activation | neutrophil, macrophage, T-cells, fibroblast, myocytes |

| IL-8 (CXCL8) | ↑ activity (N-terminus) ↓ activity (C-terminus) |

macrophage, T-cells, fibroblast, endothelial cells |

| TGF-β | Activation | macrophage, T-cells, fibroblast, endothelial cells |

| Receptors | ||

| IL-2rα | ↓ activity | macrophage, T-cells |

| CD44 | ↓ activity | macrophage, T-cells, fibroblasts |

| ITGB2 (CD18) | ↓ activity | neutrophils, macrophages |

CXCL: Chemokine (C-X-C motif) Ligand; GRO-α: Growth-regulated alpha protein; PF4: Platelet factor 4; ENA-78:Epithelial neutrophil-activating protein 78; GCP-2: Granulocyte chemotactic protein 2; MIG: Monokine induced by gamma interferon; IP10: Interferon gamma-induced protein 10; I-TAC: Interferon-inducible T-cell alpha chemoattractant; SDF-1: Stromal cell-derived factor 1; IL: Interleukin; TGF-β: Transforming growth factor beta; IL-2rα: Interleukin-2 receptor alpha; CD44: cluster of differentiation 44; ITGB2: Integrin beta-2.

2. MMP-9 Expression in Post-MI Leukocytes

Infiltrating neutrophils are a robust and early source of MMP-9 after MI, both in humans and experimental animal models.[12, 21, 22] In mice, neutrophil infiltration occurs within minutes post-MI, peaks at days 1–3, and begins to decrease by day 5. Neutrophil-derived MMP-9 is stored in gelatinase granules and subsequently released upon chemotactic stimulation. By day 7 post-MI, neutrophils numbers are returning to baseline values.[23] Neutrophils in the ischemic myocardium generate proMMP-9/αMβ2 integrin complexes within intracellular secondary granules that are translocated to the cell surface upon activation. Blocking the interaction between MMP-9 and αMβ2 inhibits leukocyte migration in vivo, indicating that integrin association with MMP-9 promotes cell migration.[13] Neutrophil-derived MMP-9 exerts early effects in the MI setting by degrading ECM and facilitating macrophage cell infiltration into the infarct area.[19, 24]

Macrophages are another rich source of MMP-9. Significant macrophage infiltration is observed at day 3 and peaks at day 5 post-MI in mice.[25] Depending on the stimulus signal, macrophages undergo classical M1 pro-inflammatory polarization or alternative anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype polarization. Pro-inflammatory M1 macrophages dominate at day 1 post-MI, while anti-inflammatory M2 macrophages dominate starting from day 3.[26] M1 macrophages contribute MMP-9 and stimulate ECM degradation, while M2 macrophages contribute growth factors that regulate fibroblast differentiation and stimulate ECM production and deposition to form the infarct scar.[24] The transition towards an M1 or M2 state is based on the local tissue environment.[27] While MMP-9 is a marker of the M1 phenotype, it also serves to polarize macrophages to the M2 phenotype by processing inflammatory molecules, including chemokine (C-X-C motif) ligand (CXCL) 4, IL-8, CXCL-12, and transforming growth factor (TGF)-β1.[28]

T-cells are key players in the adaptive immune response that also influence the post-MI wound healing process, although their mechanisms of action are not fully understood. T-cells follow the temporal dynamics trend of macrophages.[26] T-helper cells (Th1 and Th2) regulate macrophage polarization, whereas regulatory T-cells (Tregs) are beneficial post-MI by stimulating myofibroblast differentiation.[29, 30] MMP-9 regulates the proliferation of both CD4+ and CD8+ T-cells by controlling intracellular calcium influx.[31] While the process by which MMP-9 regulates T-cell inflammatory response post-MI is still under investigation, studies have shown that MMP-9 deletion reduces interleukin (IL)-2, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α and interferon (IFN)-γ gene expression in both cluster of differentiation (CD)4+ and CD8+ T cells.[31]

3. MMP-9: Cytokine and Chemokine Interactions

MMP-9 cleaves many inflammatory mediators, as demonstrated by in vitro cleavage assays (Table 1), and coordinates their function in vivo (Figure 1).[16–20] MMP-9 mediated proteolysis of cytokines and chemokines is one way by which MMP-9 influences leukocyte trafficking and creates positive or negative feedback loops.[19, 28]

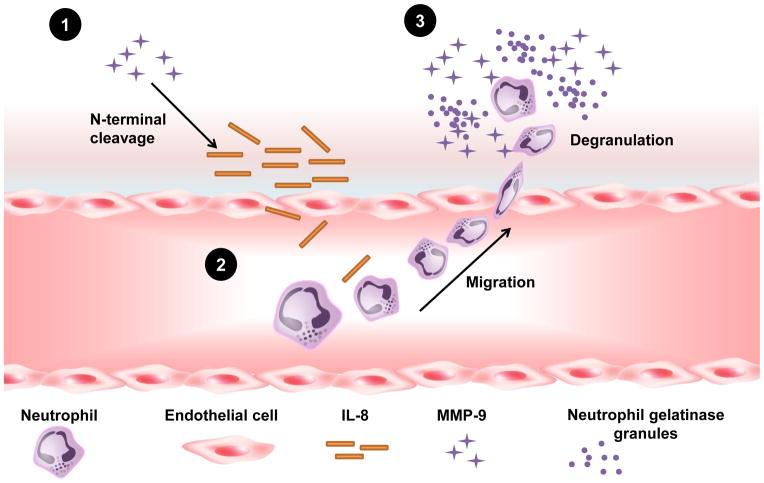

Figure 1.

A summary of the biological impact of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) on the inflammatory process during myocardial infarction (MI). Solid lines represent MMP-9 direct effects on the cytokines and chemokines described in this review. Dashed lines represent known functional relationships by Ingenuity Pathway Analysis. The network was generated using QIAGEN’s Ingenuity Pathway Analysis (IPA®, QIAGEN Redwood City, www.qiagen.com/ingenuity). CXCL: Chemokine (C-X-C motif) Ligand; MMP: matrix metalloproteinase; PF4: Platelet factor 4; IL-1β: Interleukin-1 beta; TGF-β: Transforming growth factor beta.

3.1 Inactivation of Cytokines and Chemokines by MMP-9

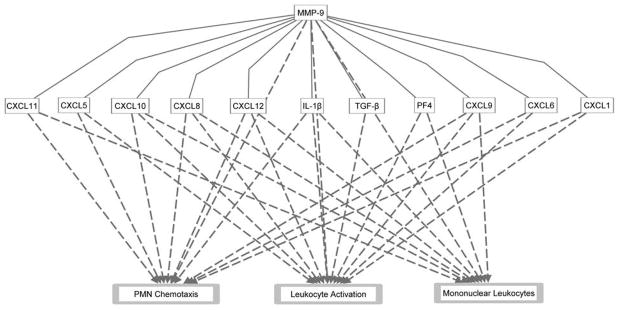

MMP-9 can inactivate chemokines to reduce chemotaxis capabilities (Figure 2). For example, MMP-9 processing of CXCL5 consists of two phases: N-terminal truncation results in a transient increase in CXCL5 activity that stimulates neutrophil recruitment, followed by subsequent further degradation leading to CXCL5 inactivation.[32] MMP-9 likewise progressively degrades CXCL1, CXCL4, and CXCL 9 as a mechanism to decrease chemotactic abilities.[33, 34] MMP-9 is also able to convert chemokines from their natural state into antagonistic derivatives that inhibit leukocyte recruitment and disrupt the inflammatory response. N-terminal truncation of CXCL11 generates an antagonistic chemokine gradient, however, upon C-terminal truncation there is a loss of activity and substrate binding.[35]

Figure 2.

A diagram illustrating activation and inactivation of cytokines and chemokines by matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9). Post-MI, a high local cytokine concentration recruits neutrophils to the infarct region (1). Neutrophils release MMP-9 containing gelatinase granules. With time, cytokine levels are reduced (2), and eventually neutrophil recruitment slows (3).

In addition to chemokines and cytokines, MMP-9 also processes receptors to consequently decrease cellular trafficking. MMP-9 cleavage of CD44, a leukocyte cell surface glycoprotein involved in cell–cell interactions, increases MMP-9 levels inducing a negative feedback loop on cellular trafficking [36]. Interleukin-2 (IL-2) receptor α is another substrate cleaved by MMP-9 to down-regulate cellular proliferative capacity by generating antagonistic soluble IL-2Rα chains.[37] The effect of IL-2Rα downregulation is immunosuppression. MMP-9 can also cleave β2 integrin (ITGB2), a receptor critical for leukocyte infiltration post-MI.[38] These results indicate that MMP-9 can blunt cell-surface mediated signaling of recruitment during MI repair.

3.2 Amplification of Cytokines and Chemokines by MMP-9

Chemokine processing by MMP-9 can also increase chemokine activity (Figure 3). For example, removal of four N-terminal residues of CXCL6 by MMP-9 increases the biological activity of CXCL6 two fold.[32] Cleavage of CXCL12 strengthens its ability to stimulate macrophage differentiation toward a pro-angiogenic and immunosuppressive cell type (M2 phenotype), demonstrating a role for MMP-9 in directly coordinating macrophage polarization.[28, 39]

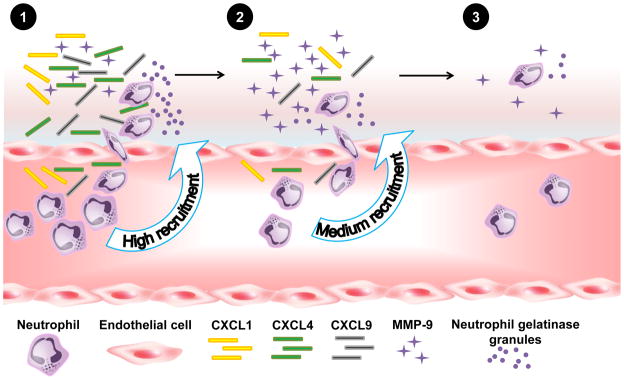

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of interleukin-8 (IL-8) activation by matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9). Following myocardial infarction (MI), neutrophils infiltrate the infarct region and release MMP-9 from gelatinase granules. IL-8 is activated by MMP-9 cleavage at its N-terminal. Active IL-8 recruits new circulating neutrophils, which release MMP-9 in a positive feedback loop.

N-terminal cleavage of IL-8, a CXC chemokine with high chemoattractive potency, results in increased IL-8 activity. IL-8 stimulates neutrophil chemotaxis and increases MMP-9 release from neutrophil granules (Figure 3). C-terminal cleavage of IL-8 results in decreased IL-8 activity. Thus, MMP-9 can initiate both positive and negative feedback loops to effect IL-8–mediated neutrophil triggering.[12, 34] Conversely, C-terminal cleavage inactivates IL-8 demonstrating the complex roles of MMP-9 regulation of the inflammatory response.[28, 40]

3.3 Activation of Cytokines and Chemokines by MMP-9

MMP-9 regulates the inflammatory response through the activation of latent inflammatory molecules. Transforming growth factor (TGF)-β is a cytokine that acts as a potent suppressor of inflammation during the final stage of wound healing.[41] Many cells, including macrophages, secrete TGF-β with its latent TGF-β binding protein. MMP-9 proteolysis of the latent complex releases a mature and active TGF-β.[42] Another positive feedback mediated by MMP-9 is the activation of IL-1β by removal of the pro-domain.[20] Active IL-1β activates neutrophils to stimulate chemotaxis in early stages of inflammation post-MI.[5, 43] MMP-9 regulation of inflammatory mediators also dictates the quality of the post-MI infarct scar, and amplified MMP-9 concentrations are linked to adverse post-MI LV remodeling.[15] As such, an appropriate level of MMP-9, inflammation, and ECM accumulation is important for post-MI infarct healing.

In vivo studies on inflammation showed that chemokines form complexes to create chemotactic gradients that provide directional cues for migrating leukocytes. By acting on these complexes, MMP-9 indirectly regulates chemokine activity and, in turn, the influx of inflammatory cells.[44] During inflammatory allergic reactions, for example, MMP-9 is required to form lung transepithelial chemokine (C-C motif) ligand (CCL)7, CCL11, and CCL17 gradients.[45] This mechanism was observed in lungs, and it would be interesting to investigate whether MMP-9 plays similar regulation in the myocardium.

4. MMP-9 as a Therapeutic Target

Many medications used to treat MI patients have both direct and indirect effects on MMP-9 production and activity. Thrombolytic agents and anticoagulants are essential for early management of patients with acute MI, however, their use as well as medications such as converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors, aldosterone antagonists, beta blockers, and statins, increase MMP-9 plasma concentrations in patients with acute MI.[46, 47] At the same time, most of these medications directly or indirectly inhibit MMP-9 activity and expression.[24, 48]

4.1 Anti-inflammatory treatments

Anti-IL-1β therapies reduce inflammation but also suppress pro-collagen expression and delay wound healing post-MI.[20, 49] The current guidelines of the American College of Cardiology Foundation and the American Heart Association, for patients who have suffered ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), or non-STEMI, recommend not using drugs that directly influence the regulation of either MMP-9 or inflammation.[50, 51] Given the dual role of MMP-9 in post-MI inflammation, focusing on cleaved substrates and their actions may be an innovative approach to selectively target out individual MMP-9 directed actions.

4.2 MMP-9 inhibitors

MMP inhibition has been widely proposed over the past 20 years. The major obstacles for developing MMP-9 inhibitors have been achieving specificity and selectivity to directly reduce only the production or activity of this MMP. Further, selective MMP-9 inhibitors designed to bind to the active motif site are subjected to active proteolysis in vivo, which limits their use.[9] To date, only one nonspecific MMP inhibitor - doxycycline (Periostat®) - has been approved by the Food and Drug Administration.[52] In vivo studies showed that doxycycline post-MI effectively suppresses MMP-2 and MMP-9 activities to attenuate myocardial fibrosis and improve LV remodeling and function.[53, 54] In the TIPTOP trial, doxycycline was shown to reduce adverse LV remodeling when given to patients with large acute MI immediately after primary percutaneous coronary intervention and in combination with standard therapy.[55]

Several selective MMP-9 inhibitors have been tested in experimental models of ischemia or in other models of cardiovascular disease. The selective MMP-9 inhibitor SB-3CT reduced hemorrhagic volumes in a model of embolic focal cerebral ischemia.[56] Inhibition of MMP-9 in a model of postoperative ileus reduced inflammation and improved motility.[57] Salvianolic acid, a competitive inhibitor of MMP-9, attenuated LV remodeling in spontaneously hypertensive rats.[58] Overall, the complex combination of MMP-9 actions suggests that a selective MMP-9 inhibitor will not guarantee beneficial results and may also be detrimental in the post-MI setting, depending on when the inhibitor is given, how much inhibition is achieved, and how long the inhibitor is continued. Given the involvement of MMP-9 in all stages of LV remodeling post-MI, the timing of MMP-9 inhibition may be the most critical aspect to consider. Timely intervention is becoming the standard in clinical practice, yet knowing when to initiate is crucial. Early therapeutic intervention sets the trajectory of LV remodeling, but there are cases when delay will be of greater benefit. Future research using drugs that actively target MMP-9 will help to define the intervention potential.

4.3 Targeting MMP-9 with microRNAs

Recent experimental data suggest microRNAs (miRNA) regulate MMP-9 expression. Bioinformatics studies revealed potential miRNA-binding sites in the 3′-UTR regions present in members of the gelatinase family.[59] Following bioinformatics analyses, several mechanistic studies have been conducted in vitro to show that miRNAs are capable of both up- and down-regulating MMP-9 expression in stromal fibroblasts and tumor tissues, namely glioma and fibrosarcoma.[60–62] For example, treatment with miR320, miR-885-5p, or miR-491-5p all individually decreased MMP-9 expression, while anti-miR320 treatment or treatment with miR-520c or miR-373 increased MMP-9 expression. Both miR-671-3p and miR-657 targeting the coding exon have also been reported to directly target a single nucleotide polymorphism on the pro-domain of MMP-9, resulting in significant decreased concentrations of secreted protein.[63] Oxidized low-density lipoprotein induced MMP-9 overexpression was attenuated after knockdown with miR-29b.[64] Li and colleagues reported increased miR-17 expression in the infarct and border zone post-MI, which decreased TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 expression and concurrently enhanced MMP-9 expression.[65] Overall, these first set of investigations introduce a compelling direction for MMP-9 intervention in the post-MI setting. Because individual miRNAs target multiple genes making specificity towards MMP-9 unlikely, additional studies looking at the overall effect of miRNA in vivo would be interesting to see how this strategy pans out as a truly selective and specific method to target MMP-9 activity.

5. Future Directions and Conclusions

An intriguing aspect that emerges from investigations on cardiac MMP-9 is its strong crosstalk with inflammation to coordinate the MI response. LV remodeling post-MI is strongly dependent on the inflammatory response, which in turn regulates scar formation. In this review, we discussed the ability of cytokines and chemokines to increase MMP-9 production. In turn, MMP-9 activates, inactivates, and stimulates the release of cytokines and chemokines to coordinate leukocyte function, forming a circular relationship. MMP-9 can therefore positively or negatively activate feedback loops to mediate the infiltration of leukocytes during LV remodeling. The imbalance of this regulation determines the outcome of the MI wound healing process, which ultimately impacts LV function. Understanding better how MMP-9 inhibition regulates cardiac inflammation, using a combination of –omics technologies coupled to in vitro examinations and in vivo animal models and human trials, are next important steps in this arena. Future studies should also focus on the optimal timing for MMP-9 targeted interventions, to provide the basis for beneficial cardiac therapeutics for the post-MI patient.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge support from NIH/NHLBI HHSN 268201000036C (N01-HV-00244) for the San Antonio Cardiovascular Proteomics Center; NIH/NHLBI for HL075360 and HL051971; NIH/NIGMS for GM104357 and GM114833; and the Biomedical Laboratory Research and Development Service of the Veterans Affairs Office of Research and Development Award 5I01BX000505.

References

- 1.Page-McCaw A, Ewald AJ, Werb Z. Matrix metalloproteinases and the regulation of tissue remodelling. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2007;8:221–233. doi: 10.1038/nrm2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vempati P, Karagiannis ED, Popel AS. A biochemical model of matrix metalloproteinase 9 activation and inhibition. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:37585–37596. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611500200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vu TH, Shipley JM, Bergers G, Berger JE, Helms JA, Hanahan D, Shapiro SD, Senior RM, Werb Z. MMP-9/gelatinase B is a key regulator of growth plate angiogenesis and apoptosis of hypertrophic chondrocytes. Cell. 1998;93:411–422. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81169-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chiao YA, Ramirez TA, Zamilpa R, Okoronkwo SM, Dai Q, Zhang J, Jin YF, Lindsey ML. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 deletion attenuates myocardial fibrosis and diastolic dysfunction in ageing mice. Cardiovascular research. 2012;96:444–455. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Halade GV, Jin YF, Lindsey ML. Matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9: A proximal biomarker for cardiac remodeling and a distal biomarker for inflammation. Pharmacology & therapeutics. 2013;139:32–40. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Turner NA, Porter KE. Regulation of myocardial matrix metalloproteinase expression and activity by cardiac fibroblasts. IUBMB life. 2012;64:143–150. doi: 10.1002/iub.594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xie Z, Singh M, Singh K. Differential regulation of matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9 expression and activity in adult rat cardiac fibroblasts in response to interleukin-1beta. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:39513–39519. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M405844200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ardi VC, Kupriyanova TA, Deryugina EI, Quigley JP. Human neutrophils uniquely release TIMP-free MMP-9 to provide a potent catalytic stimulator of angiogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2007;104:20262–20267. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706438104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yabluchanskiy A, Ma Y, Iyer RP, Hall ME, Lindsey ML. Matrix metalloproteinase-9: Many shades of function in cardiovascular disease. Physiology. 2013;28:391–403. doi: 10.1152/physiol.00029.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Castro Bras LE, Deleon KY, Ma Y, Dai Q, Hakala K, Weintraub ST, Lindsey ML. Plasma fractionation enriches post-myocardial infarction samples prior to proteomics analysis. International journal of proteomics. 2012;2012:397103. doi: 10.1155/2012/397103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dobaczewski M, Gonzalez-Quesada C, Frangogiannis NG. The extracellular matrix as a modulator of the inflammatory and reparative response following myocardial infarction. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2010;48:504–511. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2009.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lindsey M, Wedin K, Brown MD, Keller C, Evans AJ, Smolen J, Burns AR, Rossen RD, Michael L, Entman M. Matrix-dependent mechanism of neutrophil-mediated release and activation of matrix metalloproteinase 9 in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion. Circulation. 2001;103:2181–2187. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.103.17.2181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stefanidakis M, Ruohtula T, Borregaard N, Gahmberg CG, Koivunen E. Intracellular and cell surface localization of a complex between alphaMbeta2 integrin and promatrix metalloproteinase-9 progelatinase in neutrophils. Journal of immunology. 2004;172:7060–7068. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.11.7060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lindsey ML, Escobar GP, Dobrucki LW, Goshorn DK, Bouges S, Mingoia JT, McClister DM, Jr, Su H, Gannon J, MacGillivray C, Lee RT, Sinusas AJ, Spinale FG. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 gene deletion facilitates angiogenesis after myocardial infarction. American journal of physiology Heart and circulatory physiology. 2006;290:H232–239. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00457.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DeLeon-Pennell KY, de Castro Bras LE, Iyer RP, Bratton DR, Jin YF, Ripplinger CM, Lindsey ML. P. gingivalis lipopolysaccharide intensifies inflammation post-myocardial infarction through matrix metalloproteinase-9. Journal of molecular and cellular cardiology. 2014;76C:218–226. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lindsey ML, Weintraub ST, Lange RA. Using extracellular matrix proteomics to understand left ventricular remodeling. Circulation Cardiovascular genetics. 2012;5:o1–7. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.110.957803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Patterson NL, Iyer RP, de Castro Bras LE, Li Y, Andrews TG, Aune GJ, Lange RA, Lindsey ML. Using proteomics to uncover extracellular matrix interactions during cardiac remodeling. Proteomics Clin Appl. 2013 doi: 10.1002/prca.201200100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Frangogiannis NG. The inflammatory response in myocardial injury, repair, and remodelling. Nature reviews Cardiology. 2014;11:255–265. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2014.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zamilpa R, Ibarra J, de Castro Bras LE, Ramirez TA, Nguyen N, Halade GV, Zhang J, Dai Q, Dayah T, Chiao YA, Lowell W, Ahuja SS, D’Armiento J, Jin YF, Lindsey ML. Transgenic overexpression of matrix metalloproteinase-9 in macrophages attenuates the inflammatory response and improves left ventricular function post-myocardial infarction. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2012;53:599–608. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2012.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schonbeck U, Mach F, Libby P. Generation of biologically active IL-1 beta by matrix metalloproteinases: a novel caspase-1-independent pathway of IL-1 beta processing. J Immunol. 1998;161:3340–3346. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Romanic AM, Harrison SM, Bao W, Burns-Kurtis CL, Pickering S, Gu J, Grau E, Mao J, Sathe GM, Ohlstein EH, Yue TL. Myocardial protection from ischemia/reperfusion injury by targeted deletion of matrix metalloproteinase-9. Cardiovascular research. 2002;54:549–558. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6363(02)00254-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelly D, Cockerill G, Ng LL, Thompson M, Khan S, Samani NJ, Squire IB. Plasma matrix metalloproteinase-9 and left ventricular remodelling after acute myocardial infarction in man: a prospective cohort study. European heart journal. 2007;28:711–718. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ma Y, Yabluchanskiy A, Lindsey ML. Neutrophil roles in left ventricular remodeling following myocardial infarction. Fibrogenesis Tissue Repair. 2013;6:11. doi: 10.1186/1755-1536-6-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yabluchanskiy A, Li Y, Chilton RJ, Lindsey ML. Matrix metalloproteinases: drug targets for myocardial infarction. Current drug targets. 2013;14:276–286. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lindsey ML, Escobar GP, Dobrucki LW, Goshorn DK, Bouges S, Mingoia JT, McClister DM, Jr, Su H, Gannon J, MacGillivray C, Lee RT, Sinusas AJ, Spinale FG. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 gene deletion facilitates angiogenesis after myocardial infarction. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;290:H232–H239. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00457.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yan X, Anzai A, Katsumata Y, Matsuhashi T, Ito K, Endo J, Yamamoto T, Takeshima A, Shinmura K, Shen W, Fukuda K, Sano M. Temporal dynamics of cardiac immune cell accumulation following acute myocardial infarction. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2013;62:24–35. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mosser DM, Edwards JP. Exploring the full spectrum of macrophage activation. Nature reviews Immunology. 2008;8:958–969. doi: 10.1038/nri2448. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Lint P, Libert C. Chemokine and cytokine processing by matrix metalloproteinases and its effect on leukocyte migration and inflammation. J Leukoc Biol. 2007;82:1375–1381. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0607338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Weirather J, Hofmann UD, Beyersdorf N, Ramos GC, Vogel B, Frey A, Ertl G, Kerkau T, Frantz S. Foxp3+ CD4+ T cells improve healing after myocardial infarction by modulating monocyte/macrophage differentiation. Circulation research. 2014;115:55–67. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.303895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hofmann U, Beyersdorf N, Weirather J, Podolskaya A, Bauersachs J, Ertl G, Kerkau T, Frantz S. Activation of CD4+ T lymphocytes improves wound healing and survival after experimental myocardial infarction in mice. Circulation. 2012;125:1652–1663. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.044164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Benson HL, Mobashery S, Chang M, Kheradmand F, Hong JS, Smith GN, Shilling RA, Wilkes DS. Endogenous matrix metalloproteinases 2 and 9 regulate activation of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells. American journal of respiratory cell and molecular biology. 2011;44:700–708. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2010-0125OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Van Den Steen PE, Wuyts A, Husson SJ, Proost P, Van Damme J, Opdenakker G. Gelatinase B/MMP-9 and neutrophil collagenase/MMP-8 process the chemokines human GCP-2/CXCL6, ENA-78/CXCL5 and mouse GCP-2/LIX and modulate their physiological activities. European journal of biochemistry / FEBS. 2003;270:3739–3749. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2003.03760.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Van den Steen PE, Husson SJ, Proost P, Van Damme J, Opdenakker G. Carboxyterminal cleavage of the chemokines MIG and IP-10 by gelatinase B and neutrophil collagenase. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2003;310:889–896. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2003.09.098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Van den Steen PE, Proost P, Wuyts A, Van Damme J, Opdenakker G. Neutrophil gelatinase B potentiates interleukin-8 tenfold by aminoterminal processing, whereas it degrades CTAP-III, PF-4, and GRO-alpha and leaves RANTES and MCP-2 intact. Blood. 2000;96:2673–2681. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cox JH, Dean RA, Roberts CR, Overall CM. Matrix metalloproteinase processing of CXCL11/I-TAC results in loss of chemoattractant activity and altered glycosaminoglycan binding. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2008;283:19389–19399. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M800266200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chetty C, Vanamala SK, Gondi CS, Dinh DH, Gujrati M, Rao JS. MMP-9 induces CD44 cleavage and CD44 mediated cell migration in glioblastoma xenograft cells. Cellular signalling. 2012;24:549–559. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2011.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 37.Sheu BC, Hsu SM, Ho HN, Lien HC, Huang SC, Lin RH. A novel role of metalloproteinase in cancer-mediated immunosuppression. Cancer research. 2001;61:237–242. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Vaisar T, Kassim SY, Gomez IG, Green PS, Hargarten S, Gough PJ, Parks WC, Wilson CL, Raines EW, Heinecke JW. MMP-9 sheds the beta2 integrin subunit (CD18) from macrophages. Molecular & cellular proteomics : MCP. 2009;8:1044–1060. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M800449-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sanchez-Martin L, Estecha A, Samaniego R, Sanchez-Ramon S, Vega MA, Sanchez-Mateos P. The chemokine CXCL12 regulates monocyte-macrophage differentiation and RUNX3 expression. Blood. 2011;117:88–97. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-12-258186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lindsey ML, Gannon J, Aikawa M, Schoen FJ, Rabkin E, Lopresti-Morrow L, Crawford J, Black S, Libby P, Mitchell PG, Lee RT. Selective matrix metalloproteinase inhibition reduces left ventricular remodeling but does not inhibit angiogenesis after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2002;105:753–758. doi: 10.1161/hc0602.103674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shinde AV, Frangogiannis NG. Fibroblasts in myocardial infarction: a role in inflammation and repair. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2014;70:74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2013.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yu Q, Stamenkovic I. Cell surface-localized matrix metalloproteinase-9 proteolytically activates TGF-beta and promotes tumor invasion and angiogenesis. Genes & development. 2000;14:163–176. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Opdenakker G, Van den Steen PE, Dubois B, Nelissen I, Van Coillie E, Masure S, Proost P, Van Damme J. Gelatinase B functions as regulator and effector in leukocyte biology. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;69:851–859. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Parks WC, Wilson CL, Lopez-Boado YS. Matrix metalloproteinases as modulators of inflammation and innate immunity. Nature reviews Immunology. 2004;4:617–629. doi: 10.1038/nri1418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Corry DB, Kiss A, Song LZ, Song L, Xu J, Lee SH, Werb Z, Kheradmand F. Overlapping and independent contributions of MMP2 and MMP9 to lung allergic inflammatory cell egression through decreased CC chemokines. FASEB journal : official publication of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology. 2004;18:995–997. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1412fje. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tziakas DN, Chalikias GK, Hatzinikolaou EI, Stakos DA, Tentes IK, Kortsaris A, Hatseras DI, Kaski JC. Alteplase treatment affects circulating matrix metalloproteinase concentrations in patients with ST segment elevation acute myocardial infarction. Thrombosis research. 2006;118:221–227. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2005.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Castellazzi M, Tamborino C, Fainardi E, Manfrinato MC, Granieri E, Dallocchio F, Bellini T. Effects of anticoagulants on the activity of gelatinases. Clinical biochemistry. 2007;40:1272–1276. doi: 10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2007.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yamamoto D, Takai S, Jin D, Inagaki S, Tanaka K, Miyazaki M. Molecular mechanism of imidapril for cardiovascular protection via inhibition of MMP-9. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2007;43:670–676. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2007.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hwang MW, Matsumori A, Furukawa Y, Ono K, Okada M, Iwasaki A, Hara M, Miyamoto T, Touma M, Sasayama S. Neutralization of interleukin-1beta in the acute phase of myocardial infarction promotes the progression of left ventricular remodeling. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2001;38:1546–1553. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01591-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.American College of Emergency P, Society for Cardiovascular A Interventions. O’Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, Casey DE, Jr, Chung MK, de Lemos JA, Ettinger SM, Fang JC, Fesmire FM, Franklin BA, Granger CB, Krumholz HM, Linderbaum JA, Morrow DA, Newby LK, Ornato JP, Ou N, Radford MJ, Tamis-Holland JE, Tommaso CL, Tracy CM, Woo YJ, Zhao DX, Anderson JL, Jacobs AK, Halperin JL, Albert NM, Brindis RG, Creager MA, DeMets D, Guyton RA, Hochman JS, Kovacs RJ, Kushner FG, Ohman EM, Stevenson WG, Yancy CW. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2013;61:e78–140. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jneid H, Anderson JL, Wright RS, Adams CD, Bridges CR, Casey DE, Jr, Ettinger SM, Fesmire FM, Ganiats TG, Lincoff AM, Peterson ED, Philippides GJ, Theroux P, Wenger NK, Zidar JP. 2012 ACCF/AHA focused update of the guideline for the management of patients with unstable angina/non-ST-elevation myocardial infarction (updating the 2007 guideline and replacing the 2011 focused update): a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Journal of the American College of Cardiology. 2012;60:645–681. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2012.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Peterson JT. Matrix metalloproteinase inhibitor development and the remodeling of drug discovery. Heart failure reviews. 2004;9:63–79. doi: 10.1023/B:HREV.0000011395.11179.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hori Y, Kunihiro S, Sato S, Yoshioka K, Hara Y, Kanai K, Hoshi F, Itoh N, Higuchi S. Doxycycline attenuates isoproterenol-induced myocardial fibrosis and matrix metalloproteinase activity in rats. Biological & pharmaceutical bulletin. 2009;32:1678–1682. doi: 10.1248/bpb.32.1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fana XZ, Zhu HJ, Wu X, Yan J, Xu J, Wang DG. Effects of doxycycline on cx43 distribution and cardiac arrhythmia susceptibility of rats after myocardial infarction. Iranian journal of pharmaceutical research : IJPR. 2014;13:613–621. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Cerisano G, Buonamici P, Valenti R, Sciagra R, Raspanti S, Santini A, Carrabba N, Dovellini EV, Romito R, Pupi A, Colonna P, Antoniucci D. Early short-term doxycycline therapy in patients with acute myocardial infarction and left ventricular dysfunction to prevent the ominous progression to adverse remodelling: the TIPTOP trial. European heart journal. 2014;35:184–191. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/eht420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cui J, Chen S, Zhang C, Meng F, Wu W, Hu R, Hadass O, Lehmidi T, Blair GJ, Lee M, Chang M, Mobashery S, Sun GY, Gu Z. Inhibition of MMP-9 by a selective gelatinase inhibitor protects neurovasculature from embolic focal cerebral ischemia. Molecular neurodegeneration. 2012;7:21. doi: 10.1186/1750-1326-7-21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moore BA, Manthey CL, Johnson DL, Bauer AJ. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 inhibition reduces inflammation and improves motility in murine models of postoperative ileus. Gastroenterology. 2011;141:1283–1292. 1292 e1281–1284. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.06.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jiang B, Li D, Deng Y, Teng F, Chen J, Xue S, Kong X, Luo C, Shen X, Jiang H, Xu F, Yang W, Yin J, Wang Y, Chen H, Wu W, Liu X, Guo DA. Salvianolic acid A, a novel matrix metalloproteinase-9 inhibitor, prevents cardiac remodeling in spontaneously hypertensive rats. PloS one. 2013;8:e59621. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0059621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Dalmay T, Edwards DR. MicroRNAs and the hallmarks of cancer. Oncogene. 2006;25:6170–6175. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bronisz A, Godlewski J, Wallace JA, Merchant AS, Nowicki MO, Mathsyaraja H, Srinivasan R, Trimboli AJ, Martin CK, Li F, Yu L, Fernandez SA, Pecot T, Rosol TJ, Cory S, Hallett M, Park M, Piper MG, Marsh CB, Yee LD, Jimenez RE, Nuovo G, Lawler SE, Chiocca EA, Leone G, Ostrowski MC. Reprogramming of the tumour microenvironment by stromal PTEN-regulated miR-320. Nature cell biology. 2012;14:159–167. doi: 10.1038/ncb2396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yan W, Zhang W, Sun L, Liu Y, You G, Wang Y, Kang C, You Y, Jiang T. Identification of MMP-9 specific microRNA expression profile as potential targets of anti-invasion therapy in glioblastoma multiforme. Brain research. 2011;1411:108–115. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu P, Wilson MJ. miR-520c and miR-373 upregulate MMP9 expression by targeting mTOR and SIRT1, and activate the Ras/Raf/MEK/Erk signaling pathway and NF-kappaB factor in human fibrosarcoma cells. Journal of cellular physiology. 2012;227:867–876. doi: 10.1002/jcp.22993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Duellman T, Warren C, Yang J. Single nucleotide polymorphism-specific regulation of matrix metalloproteinase-9 by multiple miRNAs targeting the coding exon. Nucleic acids research. 2014;42:5518–5531. doi: 10.1093/nar/gku197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Chen KC, Wang YS, Hu CY, Chang WC, Liao YC, Dai CY, Juo SH. OxLDL up-regulates microRNA-29b, leading to epigenetic modifications of MMP-2/MMP-9 genes: a novel mechanism for cardiovascular diseases. FASEB J. 2011;25:1718–1728. doi: 10.1096/fj.10-174904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Li S-H. Abstract 12913: microRNA-17 Targets TIMP-1 and TIMP-2 to Accelerate Cardiac Matrix Remodeling After Infarction. Wolters Kluwer Health 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 66.Turner NA, Das A, O’Regan DJ, Ball SG, Porter KE. Human cardiac fibroblasts express ICAM-1, E-selectin and CXC chemokines in response to proinflammatory cytokine stimulation. The international journal of biochemistry & cell biology. 2011;43:1450–1458. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]