Abstract

WRKY transcription factor is involved in multiple life activities including plant growth and development as well as biotic and abiotic responses. We identified 28 WRKY genes from transcriptome data of Ginkgo biloba according to conserved WRKY domains and zinc finger structure and selected three WRKY genes, which are GbWRKY2, GbWRKY16, and GbWRKY21, for expression pattern analysis. GbWRKY2 was preferentially expressed in flowers and strongly induced by methyl jasmonate. Here, we cloned the full-length cDNA and genomic DNA of GbWRKY2. The full-length cDNA of GbWRKY2 was 1,713 bp containing a 1,014 bp open reading frame encoding a polypeptide of 337 amino acids. The GbWRKY2 genomic DNA had one intron and two exons. The deduced GbWRKY2 contained one WRKY domain and one zinc finger motif. GbWRKY2 was classified into Group II WRKYs. Southern blot analysis revealed that GbWRKY2 was a single copy gene in G. biloba. Many cis-acting elements related to hormone and stress responses were identified in the 1,363 bp-length 5′-flanking sequence of GbWRKY2, including W-box, ABRE-motif, MYBCOREs, and PYRIMIDINE-boxes, revealing the molecular mechanism of upregulated expression of GbWRKY2 by hormone and stress treatments. Further functional characterizations in transiently transformed tobacco leaves allowed us to identify the region that can be considered as the minimal promoter.

1. Introduction

Ginkgo biloba is the oldest relic plant among extant seed-bearing plants, usually referred to as a “living fossil” [1]. Experiencing million years of complicated climate, G. biloba not only shows strong adaptability but also exhibits minor changes in morphology. This phenomenon is possible because G. biloba can adapt to changing environments and tolerate harsh conditions [2]. Resistance genes encoding the enzymes in reactive oxygen-scavenging systems, including chloroplast copper/zinc-superoxide dismutase (GbCuZnSOD) [3], iron superoxide dismutase (GbFeSOD) [4], and manganese superoxide dismutase (GbMnSOD) [5], catalase (GbCAT1) [6], ascorbate peroxidases (GbAPX) [7], peroxidase (GbPOD1) [8], as well as dehydrin (GbDHN) [2], and GbASR [9] response to abscisic acid (ABA), stress, and ripening have been cloned from G. biloba. Studies on these genes help us to elucidate the molecular mechanism by which G. biloba tolerates severe conditions. Furthermore, stress conditions, such as drought, severe cold, harm, high temperature, and heavy metals, can stimulate accumulation and release of secondary metabolites of flavonoids and terpene lactones from G. biloba. Flavonoids and terpene lactones play an important role in improving self-protection, promoting competitive capacity, and coordinating interaction with the environment.

The WRKY family is among the ten largest families of transcription factor (TF) in higher plants and is found throughout the green lineage [10]. The defining feature of WRKY TFs is their DNA binding domain. This is called the WRKY domain containing the conserved WRKYGQK sequence at the N terminal, and as well as containing the WRKY signature it also has a typical zinc finger motif at the C terminal. The zinc finger structure is either C2H2 (CX4-5CX22-23HX1H) or C2HC (CX7CX23HX1C). Based on the number of the WRKY domains and the characteristic of a zinc finger motif, WRKY TFs can be divided into three groups: the first group contains two WRKY domains; the second group and the third group contain one WRKY domain each. The zinc finger motif of the second class is C2H2, which is the same as that of the first group; the zinc finger motif of the third group is C2HC [11].

The WRKY domain binds to what is called W-box (TTGACC/T) in the promoters of target genes. This sequence is the minimal core element necessary for binding of a WRKY protein to DNA [12]. W-box is present in the promoter of many genes related to disease resistance, damage, growth, aging, and WRKY gene, which shows that the WRKY TF is closely related to biotic and abiotic stress responses [13]. Studies have successfully used the WRKY TF to improve the stress resistance of plants. For example, single or cosilence of NaWRKY3 and NaWRKY6 can promote the susceptibility of tobacco to herbivore damage by weakening the accumulation of volatile sesquiterpene and jasmonate [14]. The resistance of Arabidopsis thaliana to the fungal disease Botrytis is also improved by overexpressing AtWRKY3 and AtWRKY4 [15]. The tolerance of rice to high temperature and drought can be improved by overexpressing OsWRKY11 [16]. The expression level of MusaWRKY71 is improved after plants suffer from cold, drought, salt, ABA, H2O2, ethephon (ETH), salicylic acid (SA), and methyl jasmonate (MeJA) in Musa spp. [17]. The expression of HbWRKY1 in latex is induced by ETH and MeJA, while the expression of HbWRKY1 in the leaf is induced by drought and ABA from Hevea brasiliensis Müll. Arg. [18].

The WRKY TF can also participate in the control of the secondary metabolism of plants except in plant defense against exogenous stress. For example, Kato et al. [19] isolated and identified the CjWRKY1 TF that controls the biosynthesis of berberine from Coptis japonica. Ectopic expression of CjWRKY1 cDNA in C. japonica protoplasts clearly increased the level of transcripts of all berberine biosynthetic genes examined compared with control treatment, indicating that CjWRKY1 is a necessary positive regulator to control overall gene expression in berberine biosynthesis. Xu et al. [20] found that GaWRKY1 gene, which encodes a protein containing a single WRKY domain, could combine with W-box in the promoter region of the key gene encoding (+)-δ-cadinene synthase to metabolize terpene and promote sesquiterpene biosynthesis. Ma et al. [21] also isolated AaWRKY1 gene from glandular secretory trichomes of Artemisia annua in which artemisinin is synthesized and sequestered. Transient expression of AaWRKY1 cDNA in A. annua leaves clearly activated the expression of the majority of artemisinin biosynthetic genes, suggesting the involvement of the AaWRKY1 TF in the regulation of artemisinin biosynthesis. Recently, Li et al. [22] and Sun et al. [23] demonstrated that a TcWRKY1 gene and a MeJA inducible PqWRKY1 gene participated in regulation of the biosynthesis of taxol in Taxus chinensis and triterpene ginsenoside in Panax quinquefolius, respectively.

To date, the WRKY genes have been cloned from many species. A total of 5,936 WRKY genes are recorded in the database of plant TFs. These genes have also been reported in 83 species, such as algae, planus, needle-leaved plant, monocotyledons, and dicotyledons. However, no cloning and the WRKY gene in G. biloba has not been found. In this report, a total of 28 unigenes of WRKY transcription factor were identified using next-generation sequencing. Among these unigenes, a MeJA-inducible WRKY gene, named GbWRKY2, was cloned from G. biloba using the rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACE) method. GbWRKY2 is preferentially expressed in flowers and induced by salinity stress and phytohormones such as SA, ETH, MeJA, and ABA but repressed by heat. Promoter analysis provided the molecular mechanism of upregulation of GbWRKY2 by phytohormones and abiotic stresses and allowed us to identify the region that can be considered as the minimal promoter. This work represents, to our knowledge, the first functional characterization of a G. biloba WRKY transcript factor.

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Plant Materials and Treatments

The 14-year-old grafts of G. biloba were grown in an orchard at Yangtze University, China. For tissue expression of GbWRKY2, GbWRKY16, and GbWRKY21, the roots, stems, leaves, and male and female flowers of G. biloba grafts were collected, immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, and kept at −80°C prior to total RNA extraction. The cultured callus lines, initiated from mature zygotic embryos of G. biloba, were maintained on liquid MS basal medium supplementing with 1.5 mg/L naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA) and 2 mg/L 6-benzyladenine (6-BA) on a rotary shaker at 100 rpm, in the light and at 25 ± 1°C. The suspension cultures were subcultured every 2 weeks and after four subcultures the differential was omitted. In the experiments for investigating induction by various elicitors, the callus lines were dipped into the appropriate treatment such as 100 μmol L−1 MeJA, 100 μmol L−1 ABA, 100 μmol L−1 SA, 40 μmol L−1 ETH, and 200 mmol L−1 sodium chloride (NaCl), respectively, using ginkgo callus without any treatment as control. The cold and heat treatments were performed by placing the callus lines in a 4°C and 40°C growth room and the control in a 25°C growth room. The callus samples were harvested 0, 3, 6, 12, 24, 48, and 72 h after treatment and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen, followed by storage at −80°C until use.

2.2. RNA and DNA Extraction

Total RNA was extracted from different tissues and all the treatments using CTAB method [42]. Genomic DNA was extracted from fresh leaves of G. biloba grafts following the CTAB method described by Xu et al. [43]. The RNA and DNA quality and quantity were determined by agarose gel electrophoresis and spectrophotometer analysis before use.

2.3. RNA-Seq Library Construction for Illumina Sequencing and Identification of WRKY Transcription Factor Gene from G. biloba Transcriptome

The extracted RNA was cleaned up using RNase-free DNaseI (Dalian TaKaRa, China) and purified using oligo-dT-attached magnetic beads. The purified mRNAs were cleaved into small pieces (200~500 bp) by super sonication. Cleaved mRNAs were used as templates to construct RNA-Seq library according to the manufacture's protocol. The constructed libraries were purified by the AMPure beads and recovered from the low melting agarose (2%) at the length of about 300 base-pair by the Qiagen Nucleic acid purification kits (CA Qiagen, USA). Sequencing run was performed on Illumina HiSeq 2500 sequencer following the manufacturer's protocols.

To obtain the complete G. biloba WRKY gene family, the male and female flowers of G. biloba transcriptome sequences were queried for 72 A. thaliana WRKY protein sequences using TBLASTN searching program. All of the collected G. biloba WRKY candidates were primarily analyzed using protein family database (Pfam) (http://pfam.xfam.org/) to confirm the presence of WRKY conserved domains on their protein structure.

2.4. Expression Analysis by Quantitative Real-Time PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed according to the instructions provided for the Applied Biosystems 7500 Real-Time PCR system (Foster City, CA, USA) and the SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (Dalian TaKaRa, China). The RNA samples were reversely transcribed using the PrimeScript RT-PCR kit (Dalian TaKaRa, China). Expression levels of WRKY genes in G. biloba were normalized using the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GbGAPDH, GenBank accession number L26924) as an internal reference gene. Based on the screened transcripts, three annotated WRKY transcripts (T2_Unigene_BMK.10348 named GbWRKY2, T1_Unigene_BMK.13300 named GbWRKY16, and T1_Unigene_BMK.18545 named GbWRKY21) were selected for expression analysis. Primers were designed using the Sequence Detection System software and shown in Table 1. qRT-PCR was performed with 20 μL reaction consisting of 2x SYBR Premix Ex Ta 10 μL, 0.4 μL each primer and 50x ROX Reference Dye II, and 100 ng cDNA as the template. The thermal cycler conditions recommended by the manufacturer were used with first stage at 95°C for 30 s, and the second stage (40 cycles) at 95°C for 5 s followed by 60°C for 34 s, and the third stage at 95°C for 15 s followed by 60°C for 1 min and 95°C for 15 s. The amplification of the target genes was monitored every cycle by SYBR green fluorescence. The Ct (threshold cycle), defined as the real-time PCR cycle at which a statistically significant increase of reporter fluorescence was first detected, was used as a measure for the starting copy numbers of the target gene. Three replicates of each experiment were performed, and data were analysed by the Livak method [44] and expressed as normalized relative expression level (2-ΔΔCT) of the respective genes in various samples. In each case, three technical replicates were performed for each of at least three independent biological replicates.

Table 1.

The primers used in this study.

| Primers | Sequence (5′-3′) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| WRKY2-FP | CCCATAATCATCCTAAGCCTCTG | Forward primer for GbWRKY2 cDNA |

| WRKY2-RP | ATGGGACACTGTATCTTGAAGTTGAG | Reverse primer for GbWRKY2 cDNA |

| WRKY2-3 | AGAAAGTAGTGAAAGGCAACCCTAACCCAA | Forward primer for 3′-RACE, outer |

| WRKY2-3N | CCATAGCACTGGCTGGTTCTCAACTTCAAG | Forward primer for 3′-RACE, nested |

| WRKY2-5 | CAACTTTGATGACAGCACCGACGCC | Forward primer for 5′-RACE, outer |

| WRKY2-5N | CGGTTAGGCAGAGGCTTAGGATGATTA | Forward primer for 5′-RACE, nested |

| WRKY2-G1 | ATGGGAGTTGGTGCTGCT | Forward primer for GbWRKY2 gDNA |

| WRKY2-G2 | TCAATGAAAAGAGGTTTCAAAGC | Reverse primer for GbWRKY2 gDNA |

| WRKY2-SP1 | CCCTTCCATCATCGTCGTCACTTGC | Reverse primer for 5′-promoter, outer |

| WRKY2-SP2 | ACGCCTTCCGCCCTTTCTCCTGCTT | Reverse primer for 5′-promoter, nested |

| WRKY2-U | AGTGCCAGCAATCAGCGTT | Gene forward primer for qRT-PCR |

| WRKY2-D | AGCCCTTGATGGGTTTCTGT | Gene reverse primer for qRT-PCR |

| WRKY16-U | ATCAGTCCACAAGCAGACCTCA | Gene forward primer for qRT-PCR |

| WRKY16-D | TTGTCATTAGCAACACTGCCATC | Gene reverse primer for qRT-PCR |

| WRKY21-U | GAATAGTATGGGTTCCAGTAGGTCG | Gene forward primer for qRT-PCR |

| WRKY21-D | AACCTTTGATAGGCTTCTGTCCA | Gene reverse primer for qRT-PCR |

| GAPDH-U | GGTGCCAAAAAGGTGGTCAT | Gene forward primer for qRT-PCR |

| GAPDH-D | CAACAACGAACATGGGAGCAT | Gene reverse primer for qRT-PCR |

| WRKY2P-1363 | AACTGCAGACTATAGGGCACGCGTGGTC | Forward primer for promoter deletion |

| WRKY2P-1018 | AACTGCAGTTCTTACGAAAGTGGTGCTGCTA | Forward primer for promoter deletion |

| WRKY2P-668 | AACTGCAGACGCATGTAGCCCTAAACCAAG | Forward primer for promoter deletion |

| WRKY2P-521 | AACTGCAGTTTGCGGTGCTTGAGCTAATT | Forward primer for promoter deletion |

| WRKY2P-288 | AACTGCAGTGTGGTGGATGCTACACCTGAG | Forward primer for promoter deletion |

| WRKY2P-137 | AACTGCAGCATAATGCCCTGTTTCCTCCAA | Forward primer for promoter deletion |

| WRKY2P-48 | AACTGCAGGCAGTGAGTATCCTCGGAGTTAT | Forward primer for promoter deletion |

| WRKY2-5UTR-F | AACTGCAGAACTAAGAAGAAGGTTGAACGGT | Forward primer for 5′-UTR |

| WRKY2P-anti | CGGGATCCGGACAATTCAAATGTGTGCACTT | Reverse primer for promoter deletion |

| WRKY2-5UTR-R | CGGGATCCTCGACGGTTAGGCAGAGGCTTA | Reverse primer for promoter deletion |

| FWR2PIN | TGAAGCAGGAGAAAGGGCGGAAGGCG | Forward primer for probe |

| RWR2PIN | CGCTGGTGCCCTTCCATCATCGTCG | Reverse primer for probe |

2.5. Cloning of the Full-Length cDNA and Genomic DNA of GbWRKY2

Two specific primers WRKY2-FP and WRKY2-RP (Table 1) were designed and synthesized (Shanghai Sangon, China) based on the transcriptome data to obtain the internal fragment. One step RT-PCR was carried out and a fragment of 689 bp was obtained by using one step RT-PCR kit (Dalian TaKaRa, China) under the following program: 50°C for 30 min and 94°C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of amplification (94°C for 1 min, 54°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min), and then followed by extension for 10 min at 72°C. The PCR product was purified and cloned into pMD18-T vector (Dalian TaKaRa, China) followed by sequencing. Subsequent BLAST results confirmed that amplified product was partial fragment of WRKY gene.

Based on the sequence of the internal fragment of GbWRKY2 gene, the specific primers WRKY2-3/WRKY2-5 and the nested primer WRKY2-3N/WRKY2-5N (Table 1) were designed to amplify the 3′ and 5′ end of the GbWRKY2 gene using the SMART RACE cDNA Amplification kit (Clontech, USA). The 3′-RACE-PCR and 5′-RACE-PCR were performed according to the manufacturer's instructions. The PCR products were purified and cloned into pMD18-T vector for sequencing. After comparing and aligning the sequence of 3′-RACE, 5′-RACE, and the internal region products, the full-length cDNA sequence of GbWRKY2 was obtained and verified through PCR amplification using 3′-Ready cDNA as the template and a pair of primers WRKY2-G1 and WRKY2-G2 (Table 1) under the following conditions: 94°C for 3 min, followed by 35 cycles of amplification (94°C for 20 s, 56°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 2 min). After sequencing, the full-length cDNA of GbWRKY2 was subsequently analyzed for molecular characterization. Two gene-specific primers, WRKY2-G1 and WRKY2-G2, designed based on the cDNA sequence were used to amplify the genomic sequence of GbWRKY2.

2.6. Amplification of the Promoter Region of GbWRKY2

Ginkgo genome walker libraries were constructed using the Genome Walker Universal Kit User (Clontech, USA). To clone the promoter region of GbWRKY2, two round PCR were performed using gene-specific primers (WRKY2-SP1 and WRKY2-SP2) that were designed according to the sequence of GbWRKY2 cDNA and the adapter primers (AP1 and AP2) provided by the kit. Their sequences were shown in Table 1. After the nested PCR was carried out, amplified fragments were cloned and then sequenced. The sequences that extended upstream of the cDNA of GbWRKY2 were isolated as the 5′-upstream region of GbWRKY2 gene and used for further analysis.

2.7. Promoter Deletion-GUS Constructs and Agrobacterium-Mediated Transient Expression Assay

For construction of the GbWKRY2 promoter-driven GUS fusion genes, the GbWRKY2 promoter fragment-covering regions were amplified by PCR. Forward primers (Table 1) were designed to correspond to the −1363, −1018, −721, −668, −521, −288, −137, and −48 of GbWRKY2 promoter and reverse primers, WRKY2P-anti and WRKY2-5UTR-R, were complementary to the 3′-end sequence of GbWRKY2 promoter and 5′-UTR region, respectively. In addition, a supplementary fragment was amplified using primers WRKY2-1363 and WRKY2P-anti lacking the 5′-UTR region of GbWRKY2. Each fragment was digested with PstI/BamHI and subcloned into PstI/BamHI-digested pBI121 to generate seven promoter deletion derivatives. The promoterless construct (pBI121) was used as negative control. All constructs were verified by sequence analysis. Each promoter-GUS fusion construct was introduced into A. tumefaciens LBA4404 via electroporation. Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression assays were performed according to the method of An et al. [45]. Agrobacterium-mediated transient expression was conducted on fully expanded tobacco leaves, and the intercellular spaces of the intact leaves were infiltrated with the bacterial suspension. After agroinfiltration, tobacco plants were maintained in a moist chamber at 24°C for 48 h. The GUS activity was examined in the tobacco leaves coinfiltrated with Agrobacterium strains harboring different GbWRKY2 promoter-GUS fusion constructs.

2.8. GUS Activity Assay

The seedlings of tobacco transformant were ground in liquid nitrogen. The crude proteins were extracted with 50 mM phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, containing 10 mM β-mercaptoethanol, 10 mM EDTA, and 0.1% Trition X-100. Homogenates were cleared by centrifugation, and the supernatants were assayed by Bradford assay for total protein (DU700, Beckman, Germany). GUS activity was measured as described by Jefferson et al. [46].

2.9. Southern Blot Analysis

Aliquots of DNA (30 μg/sample) were digested overnight at 37°C with BamHI and PstI, respectively, which does not cut within the probe region, fractionated by 0.85% agarose gel electrophoresis and transferred to a Hybond-N+ nylon membrane (Amersham Pharmacia, UK). The 283-bp probe was generated by PCR using genomic sequence of GbWRKY2 including intron as template with primers FWR2PIN and RWR2PIN (Table 1). Probe labeling (biotin), hybridization, and signal detection were performed using Gene Images random prime labeling module and CDP-Star detection module following the manufacturer's instructions (Amersham Pharmacia, UK). The film was washed under stringent conditions (60°C) and signals were visualized by exposure to Fuji X-ray film at room temperature for 1.5 h.

2.10. Bioinformatic Analysis and Molecular Evolution Analyses

The obtained sequences were analyzed using bioinformatic tools at websites (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov and http://www.expasy.org/). The software vector NTI Suite 10 was used for sequence multialignment. The isolated 5′-upstream sequence was analyzed for the putative cis-acting regulatory elements using the PLACE (http://www.dna.affrc.go.jp/PLACE/) and the Signal Scan Program PlantCARE (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/) database. Phylogenetic tree analysis of GbWRKY2 and known WRKYs from other plant species retrieved from GenBank were aligned with CLUSTAL W. Subsequently, a phylogenetic tree was constructed by neighbor-joining (NJ) method. The reliability of the tree was measured by bootstrap analysis with 1000 replicates.

3. Results

3.1. WRKY Candidate Genes Were Identified in G. biloba Transcriptome

Transcriptomes of male and female flowers from G. biloba were sequenced using Illumina RNA-seq technology, yielding 20 and 19 million transcript reads, respectively. Using the PFAM protein family database with the WRKY domain (PF03106), we identified a total of 28 WRKY transcription factors (Table 2). There were differences in the lengths of proposed sequences of 28 WRKY genes, ranging from 258 bp to 2325 bp. These differences may have been due largely to assembly error in partial chromosomal regions and require further confirmation. Gene expression level was estimated using RPKM (reads per kilobase per million mapped reads) value. Among these 28 WRKY transcripts, 20 WRKY genes were identified to be highly expressed in male flowers and the others were highly expressed in female flowers. Subsequently, we selected GbWRKY2, GbWRKY16, and GbWRKY21 for expression analysis.

Table 2.

The WRKY transcription factors in G. biloba.

| Sequence ID∗ | RPKM | CDs (bp) | Annotation to the Arabidopsis WRKYs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male flower | Female flower | |||

| T1_Unigene_BMK.14363 | 10.97 | 13.00 | 2583 | WRKY2 |

| CL11186Contig1 | 21.20 | 5.54 | 1977 | WRKY4 |

| T1_Unigene_BMK.20451 | 15.23 | 38.68 | 2019 | WRKY3 |

| CL8351Contig1 | 7.37 | 10.07 | 2037 | WRKY4 |

| CL1197Contig1 | 7.25 | 14.22 | 2325 | WRKY20 |

| CL6861Contig1 | 50.14 | 3.48 | 2121 | WRKY31 |

| T1_Unigene_BMK.5610 | 1.92 | 0.00 | 783 | WRKY61 |

| CL6024Contig1 | 3.55 | 2.24 | 1338 | WRKY57 |

| CL10281Contig1 | 12.46 | 3.65 | 744 | WRKY28 |

| T1_Unigene_BMK.13300 | 23.85 | 18.55 | 1068 | WRKY21 |

| CL7955Contig1 | 68.18 | 44.85 | 1206 | WRKY11 |

| T1_Unigene_BMK.24659 | 7.59 | 0.45 | 1281 | WRKY42 |

| CL10826Contig1 | 2.54 | 1.29 | 1374 | WRKY14 |

| T1_Unigene_BMK.18545 | 25.53 | 3.26 | 642 | WRKY16 |

| T2_Unigene_BMK.20037 | 15.38 | 39.75 | 1440 | WRKY4 |

| CL7159Contig1 | 11.59 | 6.68 | 1086 | WRKY21 |

| T1_Unigene_BMK.7872 | 3.06 | 1.19 | 900 | WRKY31 |

| T2_Unigene_BMK.15740 | 11.05 | 13.52 | 1806 | WRKY2 |

| CL2657Contig1 | 2.31 | 23.10 | 804 | WRKY71 |

| CL3411Contig1 | 5.22 | 1.97 | 1527 | WRKY48 |

| T2_Unigene_BMK.8142 | 21.95 | 18.36 | 1068 | WRKY21 |

| CL11312Contig1 | 32.03 | 14.08 | 1101 | WRKY7 |

| T2_Unigene_BMK.4532 | 0.08 | 1.46 | 258 | WRKY12 |

| T2_Unigene_BMK.10348 | 10.05 | 2.10 | 808 | WRKY2 |

| T2_Unigene_BMK.10347 | 18.22 | 4.04 | 915 | WRKY2 |

| CL1517Contig1 | 22.31 | 6.87 | 1080 | WRKY21 |

| T2_Unigene_BMK.9572 | 0.13 | 2.84 | 1404 | WRKY49 |

| CL4085Contig1 | 1.76 | 0.69 | 378 | WRKY23 |

∗The candidate gene is indicated in bold.

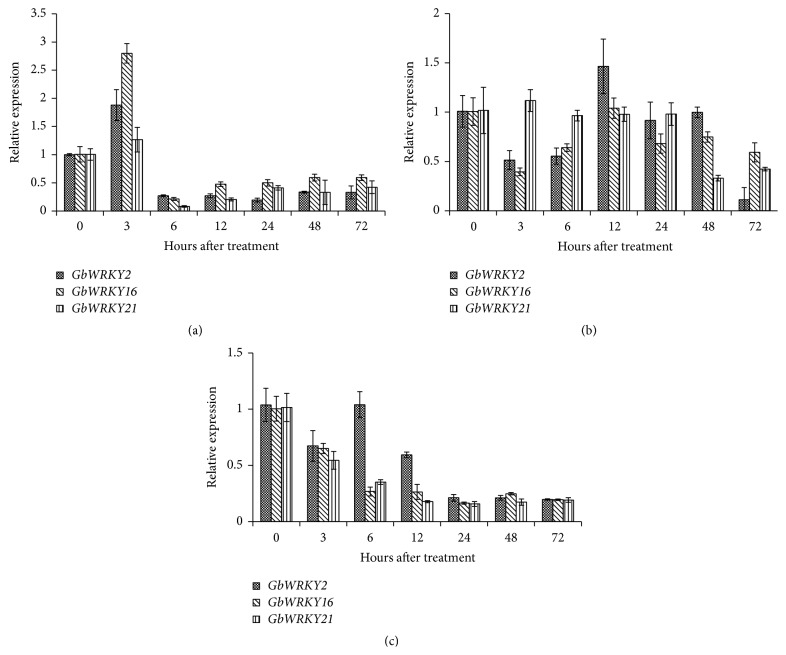

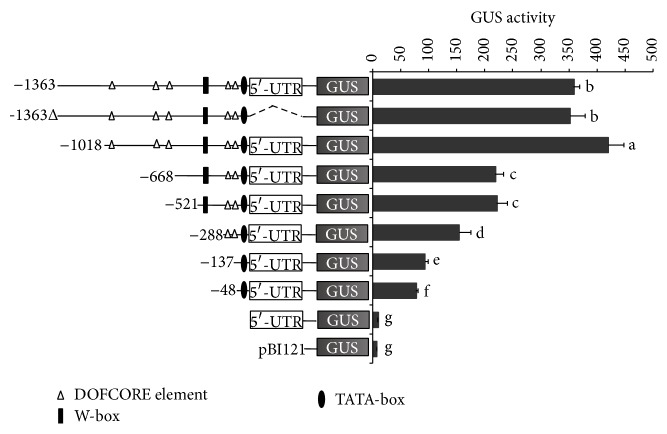

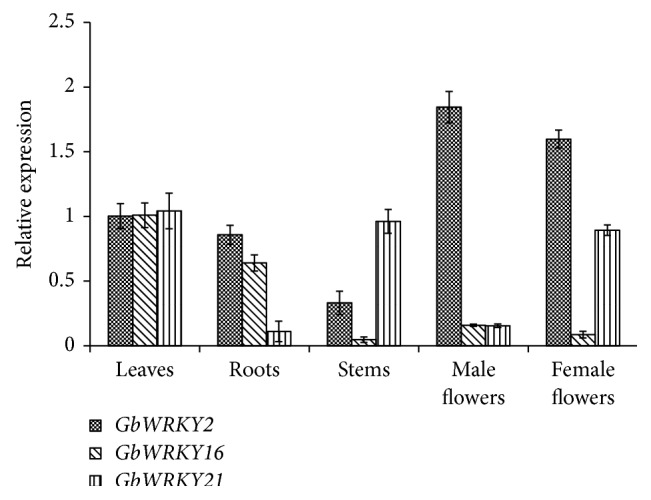

3.2. Expression Analysis in Different Tissues

The expression profile of GbWRKY2, GbWRKY16, and GbWRKY21 was assessed by qRT-PCR in leaves, roots, stems, and male and female flowers of 14-year-old graft ginkgo trees (Figure 1). The results showed that all of three genes transcripts could be detected in all tissues, but at different expression levels. The highest expression level of GbWRKY2 was observed in flowers and significantly higher than in the leaves and roots. The lowest expression level of GbWRKY2 was observed in stems and was significantly lower (P < 0.05) in other tissues. In contrast, the expression level of GbWRKY16 was very low in flowers, and the expression level of GbWRKY21 was significantly higher in leaves, stems, and female flowers than in roots and male flowers.

Figure 1.

The expression levels of GbWRKY2, GbWRKY16, and GbWRKY21 in Ginkgo biloba different tissue. Relative expression levels of GbWRKY2, GbWRKY16, and GbWRKY21 in different tissues with GbGAPDH gene as internal reference gene. Total RNA samples were isolated from leaves, roots, stems, male flowers, and female flowers, respectively. Each sample was individually assayed in triplicate. Values shown represent the mean reading from three plants and the error bars indicated the standard errors of the mean.

3.3. Effect of Abiotic Stresses on the Expression of Three WRKY Genes

To determine the function of GbWRKY2, GbWRKY16, and GbWRKY21 in response to abiotic stress, we investigated the time-course expression patterns of these three genes in gingko callus treated with NaCl, cold, and heat. As shown in Figure 2(a), GbWRKY2 and GbWRKY16 transcript levels were enhanced by NaCl, showing a 1.9-fold and 2.8-fold, respectively, compared with the control at 3 hpt (hours after treatment). Afterwards, the transcript levels of these two genes were decreased sharply after 6 hpt. GbWRKY21 transcript level was increased slightly and then decreased along with the treatment. GbWRKY2 transcript levels were also somewhat enhanced by low temperature (4°C) at 12 hpt (Figure 2(b)) but were decreased slightly along with the treatment time under high temperature (40°C) stress (Figure 2(c)). The relative expressions of WRKY16 and GbWRKY21 were significantly decreased under both low and high temperature treatments (Figure 2(c)).

Figure 2.

Relative expression levels of GbWRKY2, GbWRKY16, and GbWRKY21 under salinity (a), cold (b), and heat (c) treatments. Relative expression of GbWRKY2, GbWRKY16, and GbWRKY21 at various hours after treatment under salinity, cold, and heat treatments with GbGAPDH gene as internal reference gene. Each sample was individually assayed in triplicate. Values shown represent the mean reading from three treated samples and the error bars indicated the standard errors of the mean.

3.4. Effect of Hormones on the Expression of Three WRKY Genes

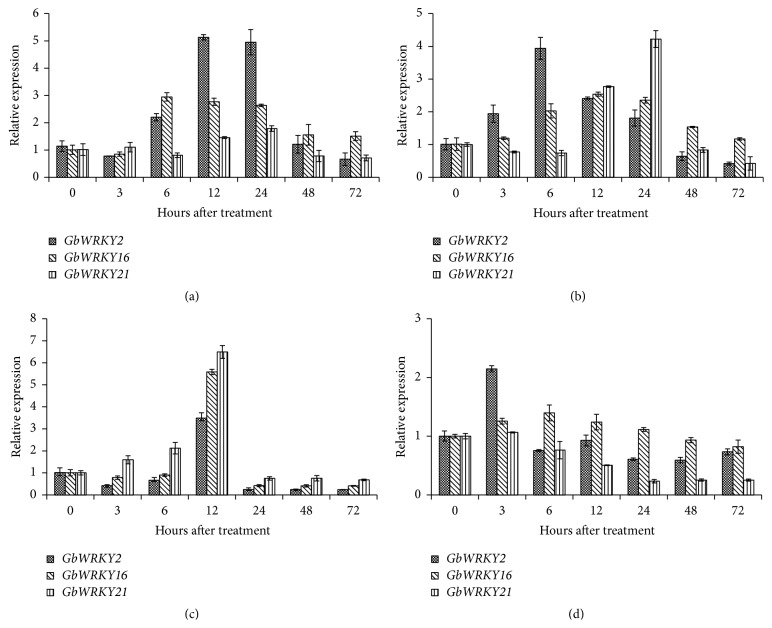

Phytohormones, such as SA, MeJA, ABA, and ETH, serve as important signaling molecules and play crucial roles in controlling the expression of downstream defense genes and physiological reactions against biotic and abiotic stresses. To assess the possible involvement of three WRKY genes in signaling pathways utilized by these hormones, the transcript level of GbWRKY2, GbWRKY16, and GbWRKY21 in ginkgo callus was determined by qRT-PCR treated with ABA, SA, ETH, and MeJA. All the transcript levels of the GbWRKY2, GbWRKY16, and GbWRKY21 were significantly (P < 0.05) increasingly treated with ABA compared with the control. The strongest response of GbWRKY2 (5.1-fold compared with the control), GbWRKY16 (2.9-fold compared with the control), and GbWRKY21 (1.8-fold compared with the control) to ABA treatment was observed at 12, 6, and 24 hpt, respectively (Figure 3(a)).

Figure 3.

Relative expression levels of GbWRKY2, GbWRKY16, and GbWRKY21 with ABA (a), SA (b), ETH (c), and MeJA (d) treatments. Relative expressions of GbWRKY2, GbWRKY16, and GbWRKY21 at various hours after treatment under ABA, SA, ETH, and MeJA treatments with GbGAPDH gene as internal reference gene. Each sample was individually assayed in triplicate. Values shown represent the mean reading from three treated samples and the error bars indicated the standard errors of the mean.

In regard to SA, GbWRKY2 transcript level was increased between 3 and 24 hpt (Figure 3(b)). The highest levels of GbWRKY2 transcript level (3.9-fold compared with the control) were reached at 6 hpt. GbWRKY16 transcript level was sustainably upregulated during SA treatment and the highest level of GbWRKY16 (2.5-fold compared with the control) was reached at 12 hpt. In contrast, GbWRKY21 transcript level was firstly decreased after treatment and increased between 12 and 24 hpt, treated with SA compared with the control. The strongest response to SA (4.2-fold compared with the control) was observed at 24 hpt.

Figure 3(c) showed that the transcript levels of GbWRKY2 and GbWRKY16 were decreased sharply before 12 hpt but enhanced rapidly and reached the peak, nearly 3.5-fold and 5.6-fold compared with the control, respectively, under ETH treatment. GbWRKY21 transcript level was continuously upregulated until 12 hpt reaching a 6.5-fold compared with the control and then was decreased.

For MeJA treatment, GbWRKY2 transcript level was significantly (P < 0.05) induced between 0 and 3 hpt, after which they decreased to the similar level to the control (Figure 3(d)). In contrast to GbWRKY2, no significant effect of MeJA was observed in GbWRKY16 transcript level, while GbWRKY21 transcript level was significantly (P < 0.05) decreased by MeJA.

3.5. Cloning of GbWRKY2 and Its Sequence Analysis

The WRKY genes have previously been determined to respond to MeJA and are involved in many life processes, including stress resistance [47], secondary metabolism [23], and plant defense [48]. The exploration of the function of MeJA-inducible WRKY genes in G. biloba would be beneficial for discovering genes involved in stress resistance and in secondary metabolite biosynthesis in G. biloba. Since qRT-PCR analysis indicated that GbWRKY2 might be involved in the signal transduction of MeJA in stress resistance of ginkgo, we cloned the full-length cDNA, genomic DNA, and promoter region of GbWRKY2 to further study the function of GbWRKY2 in stress defense.

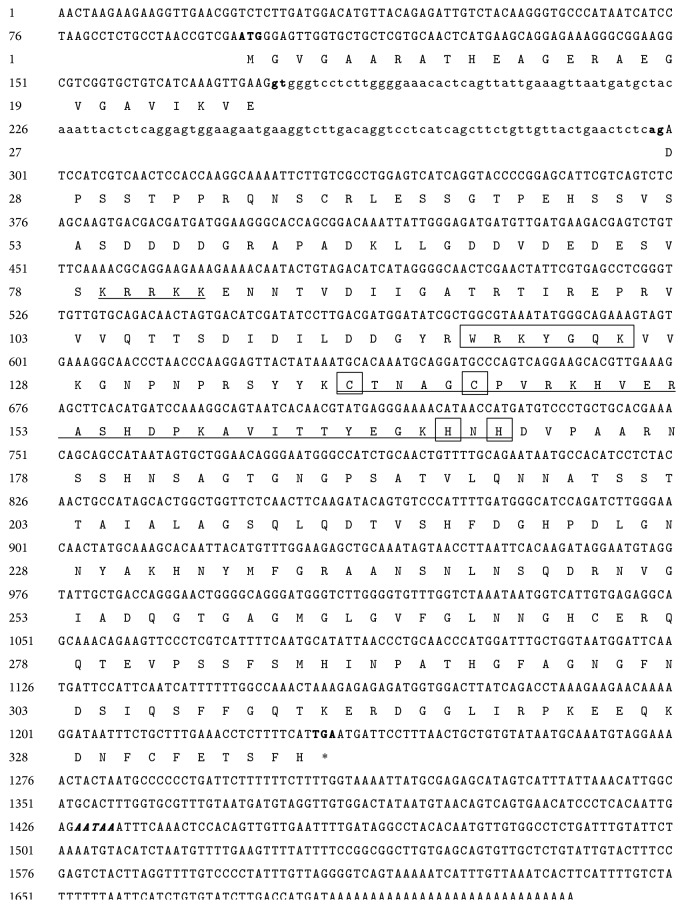

The full-length cDNA of GbWRKY2 (GenBank accession number KP987204) was 1,713 bp and contained a 1,014 bp open reading frame encoding a 337 amino acid proteins. One possible polyadenylation signal (AATAA) was found at 194 bp position downstream from the stop codon (Figure 4). A pair of specific primers was designed to synthesize cDNA between the start codon and the terminator codon of GbWRKY2. The genomic sequence of GbWRKY2 (GenBank accession number KP987205) with a length of 1,137 bp was amplified and exhibited 100% identity of the coding region of the full-length cDNA sequence. The genomic sequence of GbWRKY2 contained one intron with a length of 123 bp. This intron was smaller than that of Arabidopsis (241 bp) and rice (868 bp). The putative splicing site obeyed the GT/AG rule [11] (Figure 4). Compared with the identities of the nucleotides of other plants in NCBI, the identities of GbWRKY2 with the nucleotide sequence of the WRKY gene from Picea glauca, P. sitchensis, Amborella trichopoda, Medicago truncatula, and Morus notabilis were 83%, 82%, 81%, 81%, and 83%, respectively.

Figure 4.

The full-length cDNA, intron, and deduced amino acid sequence of GbWRKY2 gene. The exons sequence is indicated in capital letter and the intron is indicated in lowercase. The start codon (ATG), the stop (TAG), and putative exon-intron splicing sites (gt/ag) are shown by bold letters. One putative polyadenylation signal is bold and italic. A putative nuclear localization signal is underlined. The WRKY domain and the C and H residues in the zinc finger motif (CX4CX23HX1H) are boxed. The zinc finger motif (CX4CX23HX1H) is marked by underline.

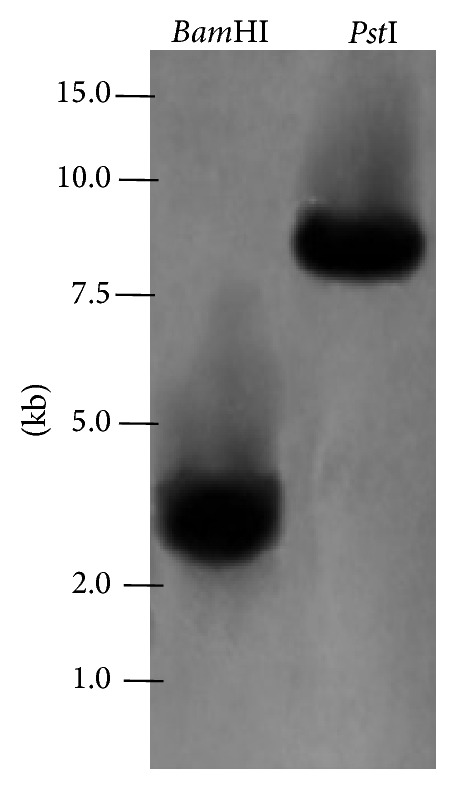

3.6. Southern Blot Analysis

To investigate the genomic organization of GbWRKY2, we carried out a Southern blot analysis by digesting genomic DNA of G. biloba with BamHI and PstI, followed by hybridization with a 283 bp probe generated by PCR using the genomic sequence of GbWRKY2 as template. As shown in Figure 5, only one hybridized band was detected in each lane, indicating that GbWRKY2 was a single copy gene in G. biloba.

Figure 5.

Southern blot analysis of GbWRKY2. Genomic DNA of G. biloba was digested with BamHI and PstI, separated on a 0.85% agarose gel, blotted onto a positively charged nylon membrane and probed with a biotin-labeled GbWRKY2 fragment.

3.7. Analysis of GbWRKY2 Protein

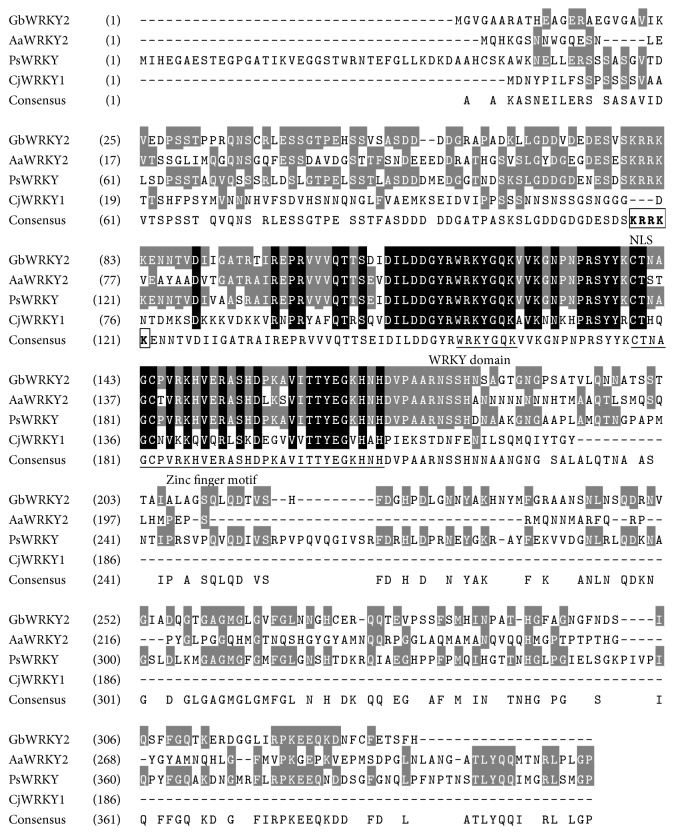

The GbWRKY2 was predicted to encode a protein of 337 amino acid residues. The relative molecular mass and theoretical isoelectric point (pI) of the predicted protein were 36.25 kDa and 6.16, respectively. BLASTP analysis in NCBI revealed that the deduced GbWRKY2 amino acid showed high identity to known WRKY TFs from other plants (Figure 6). The analysis of the deduced amino acid revealed that GbWRKY2 contained one conserved WRKY domain and a zinc finger motif of C2H2 (Figure 6), suggesting GbWRKY2 is a member of the WRKY II family [10, 11]. Like other members of WRKY II family, the conserved domain zinc finger motif for binding Zn+2 ion required for protein function presents at similar positions in GbWRKY2. In addition, sequence analysis using WoLF PSORT (http://www.genscript.com/psort/wolf_psort.html) indicated that the predicted GbWRKY2 protein contains a putative nuclear localization signal (78KRRKK82). All the observed conservations of these domains and motifs in all aligned sequences, especially in G. biloba, suggested the function of the GbWRKY2 protein.

Figure 6.

Sequence multialignment of the deduced GbWRKY2 protein with other WRKYs. The completely identical amino acids are indicated with white foreground and black background. The conserved amino acids are indicated with white foreground and grey background. Nonsimilar amino acids are indicated with black foreground and white background. The WRKY domain and zinc finger motif (CX4CX23HX1H) are underlined. A putative nuclear localization signal (KRRKK) is shown by bold letters and boxed. The GenBank accession numbers of WRKY proteins and translation of their names are shown as follows: GbWRKY2: Ginkgo biloba; CjWRKY1: Coptis japonica var. dissecta BAF41990.1; PsWRKY: Picea sitchensis ADE77055.1; AaWRKY2: Artemisia annua AGR40498.1.

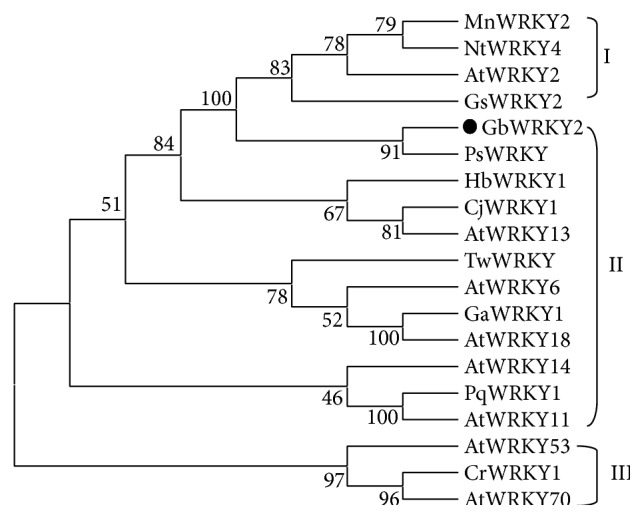

To investigate the evolutionary relationships among GbWRKY2 and other WRKY TF proteins, the phylogenetic tree was constructed using neighbor-joining method (Figure 7). The results showed a total of 19 WRKY proteins divided into three classes. Among these proteins, MnWRKY2, NtWRKY4, GsWRKY2, and AtWRKY2 belonged to class I; AtWRKY53, AtWRKY70, and CrWRKY1 belonged to class III. GbWRKY2, HbWRKY1, CjWRKY1, TwWRKY, and GaWRKY1, as well as PqWTKY1, clustered in Group II. Furthermore, GbWRKY2 and PsWRKY of gymnospermae clustered in the same branch, implying that these two WRKY TFs may exhibit a close genetic relationship and display similar protein function.

Figure 7.

Phylogenetic tree of the sequences of GbWRKY2 and other plants WRKY protein. The numbers at each node represented the bootstrap values (with 1000 replicates). The GenBank accession numbers of WRKY proteins and translation of their names are shown as follows: GbWRKY2: Ginkgo biloba; MnWRKY2: Morus notabilis XP_010092241.1; NtWRKY4: Nicotiana tabacum BAA86031.1; AtWRKY2: Arabidopsis thaliana AED96743.1; GsWRKY2: Glycine soja KHN40472.1; PsWRKY: Picea sitchensis ADE77055.1; HbWRKY1: Hevea brasiliensis ADF45433.1; CjWRKY1: Coptis japonica var. dissecta BAF41990.1; AtWRKY13: Arabidopsis thaliana AEE87071.1; TwWRKY: Taxus wallichiana var. chinensis AEW91476.1; AtWRKY6: Arabidopsis thaliana AEE33948.1; GaWRKY1: Gossypium arboreum AAR98818.1; AtWRKY18: Arabidopsis thaliana AEE85961.1; AtWRKY14: Arabidopsis thaliana AEE31256.1; PqWRKY1: Panax quinquefolius AEQ29014.1; AtWRKY11: Arabidopsis thaliana AEE85928.1; AtWRKY53: Arabidopsis thaliana AEE84809.1; CrWRKY1: Catharanthus roseus HQ646368; AtWRKY70: Arabidopsis thaliana AEE79517.1.

3.8. Analysis of 5′-Flanking Sequence of GbWRKY2

Based on the DNA sequence of GbWRKY2 gene, the nested primer is designed, and the 5′-flanking sequence (KP987205) with 1,363 bp of GbWRKY2 was isolated by genome walking method. Taking into account the result of 5-RACE PCR, we concluded the initiation site of GbWRKY2 transcription at −97 bp in the upstream of ATG (Figure 1S in the Supplementary Material available online at http://dx.doi.org/10.1155/2015/607185). The promoter region of GbWRKY2 possessed a typically high A + T content of 58.0%, which was commonly found in other plant promoters. The promoter region of GbWRKY2 was then submitted to PLACE and PlantCARE databases for the analysis of putative cis-element. The result showed that the TATA box was located at −26 bp in the upstream of the transcription initiation site. Another conserved eukaryotic cis-element, the CAAT box, was also found at 232, 787, and 824 bp (Figure 1S), consistent with typical characteristics of the plant promoter. Other stress-related cis-elements were also observed in the promoter region of GbWRKY2 (Table 3). For example, one low temperature response (CRTDREHVCBF2) [30], two drought stress response and aging response (ACGTATERD1) [27], and four disease defense (BIHD1OS) [28] cis-elements were found. Motifs related to light regulation, including three GT1 [49] and one IBOX [36], were also detected. Furthermore, cis-acting elements related to hormones were also predicted (Figure 1S). For example, we found one core motif for binding DPBF TF, three GT1 motifs, seven ARR1AT TF binding sites, and four PYRIMIDINE-boxes that participate in the signal response of ABA, salicylic acid, cytokinin, and gibberellin [26, 32, 39, 49], respectively, in the promoter region of GbWRKY2. Two ABA response cis-elements were also found at 10 and 585 bp position [24, 25]. Moreover, some TF binding sites were also detected. For example, five Dof TF binding sites were found in the promoter region of GbWRKY2, and these motifs participate in the signal response of auxin [50], jasmonic acid, or ethylene [51] in other plants. In addition, we found ten E-boxes, five MYB-boxes, nine MYC-boxes, and one W-box in GbWRKY2 promoter, which is conservative binding motif of bHLH [33], MYB [38], MYC [37], and WRKY [12] TFs, respectively. Interestingly, the presence of a putative W-box binding site within the GbWRKY2 promoter might indicate that this ginkgo gene can be subjected to autoregulation or can be modulated by other WRKY members [52, 53]. Prediction results showed that the regulatory cis-elements of GbWRKY2 promoter were related to stress-induced response, indicating that the promoter may play an important role in response to external environmental stress and biological defense process.

Table 3.

Putative cis-acting regulatory elements identified in the promoter of GbWRKY2 using PLACE (http://www.dna.affrc.go.jp/PLACE/) and the Signal Scan Program PlantCARE (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/) database.

| Name of cis-element | Position | Signal sequence | Function | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ABRELATERD1 | 585 | ACGTG | ABA-responsive elements | [24] |

|

| ||||

| ABRERATCAL | 10 | MACGYGB | Ca2+-responsive and ABA upregulated genes | [25] |

|

| ||||

| ARR1AT | 629, 634, 564, 90, 751, 883 | NGATT | ARR1 binding element involved in cytokinin signaling | [26] |

|

| ||||

| ACGTATERD1 | 262, 585 | ACGT | Involved in upregulation by dehydration stress and dark-induced senescence | [27] |

|

| ||||

| BIHD1OS | 595, 772, 863, 1307 | TGTCA | BELL recognition site involved in disease resistance responses | [28] |

|

| ||||

| CAATBOX1 | 232, 787, 824 | CAAT | Common cis-acting element in promoter and enhancer regions | [29] |

|

| ||||

| CRTDREHVCBF2 | 18 | GTCGAC | Low-temperature responsive | [30] |

|

| ||||

| DOFCOREZM | 354, 621, 687, 1258, 1301 | AAAG | Dof1 and Dof2 binding element involved in carbon metabolism | [31] |

|

| ||||

| DPBFCOREDCDC3 | 1089 | ACACNNG | DPBF-1 binding core sequence involved in ABA signaling | [32] |

|

| ||||

| EBOXBNNAPA | 86, 232, 318, 714, 729, 775, 1090, 1246, 1280, 1350 | CANNTG | Cis-element binding BHLH factor is dispensable for light responsiveness | [33] |

|

| ||||

| GATABOX | 124, 222, 290, 640, 681, 1253, 1276 | GATA | Common cis-acting element in promoter | [34] |

|

| ||||

| GT1CONSENSUS | 475, 803, 928 | GRWAAW | Consensus GT-1 binding site in many light-regulated genes and influence the level of SA-inducible gene expression | [35] |

|

| ||||

| IBOX | 124 | GATAAG | Conserved sequence upstream of light-regulated genes | [36] |

|

| ||||

| MYB2CONSENSUSAT | 318, 1246, 1280, 591 | YAACKG | MYB recognition site involved in dehydration responsiveness | [37] |

|

| ||||

| MYCCONSENSUSAT | 86, 232, 318, 714, 729, 775, 1090, 1246, 1280 | CANNTG | MYC recognition site involved in dehydration responsiveness and cold responsiveness | [38] |

|

| ||||

| PYRIMIDINE-box | 214, 840, 869, 890 | CCTTTT | Gibberellin-response cis-element | [39] |

|

| ||||

| ROOTMOTIFTAPOX1 | 178, 223, 546, 641, 722 | ATATT | Root specific expression | [40] |

|

| ||||

| TATA box | 94 | TTATTT | Common cis-acting element in promoter and enhancer regions | [41] |

|

| ||||

| WBOXATNPR1 | 887 | TTGACY | WRKY binding site, involved in many physiological processes | [10] |

3.9. Deletion Analysis of the GbWRKY2 Promoter in Tobacco Leaf Tissues

To gain insight into the functional role of the GbWRKY2 promoter region, series deletions were sequential of the cis-elements and fusion of the remaining promoter to the GUS reporter gene was constructed. A promoterless construct (pBI121) was used as a negative control (Figure 8). Sequential 5′-deletions of the promoter were performed by PCR, and the responsiveness of the deleted versions of the GbWRKY2 promoter was analyzed by transient assays in tobacco leaves. As shown in Figure 8, the GUS activity of the maximum-length containing 5′-UTR of GbWRKY2 (construct −1363) was 358.36 nM 4-methylumbelliferone (MU) mg−1 protein min−1, although the GUS activity (352.19 nM 4-mg−1 protein min−1) of 5′-UTR deletion of full-length promoter (−1363Δ) was slightly less than that of construct −1363 but did not reach significant level (P > 0.05), suggesting that 5′-UTR had no effect on the transcript level of GbWRKY2 promoter under our experimental condition. The highest level of GUS activity was observed in transgenic tobacco leaves harboring the −1018 promoter construct and significantly higher (P < 0.05) than that of the full-length promoter (construct −1363), implying that negative cis-elements may be present in the promoter region between −1363 and −1018. By contrast, deletion of the GbWRKY2 promoter from −1018 to −668 caused a significant (P < 0.05) reduction of the promoter expression. Successive deletion from −668 to −521 had no additional significant effect on GUS activity while further deletion to −228 containing a W-box causes a significant (P < 0.05) decrease of GUS activity. Likewise, both further deletions from −228 to −137 and from −137 to −48 led to 39.3% and 16.7% decrease of promoter expression, respectively. Finally, both the constructs containing 5′-UTR and negative constructs present a quasicomplete disappearance of GUS activity, suggesting 5′-UTR region had no contribution to GbWRKY2 expression.

Figure 8.

Deletion analysis of the GbWRKY2 promoter-driven GUS activity. Schematic diagram of the constructs used for GUS activity assays in leaves of transgenic tobacco plants is shown at left. Dash line pinpoints the deletion of the 5′-UTR region for the construct −1363Δ. Quantitative analyses of GUS activity of transgenic plants driven by deletion constructs of the GbWRKY2 promoter are shown at right. Error bars represent standard deviation (SD). Data are mean ± SD from triplicate experiments. Values with different letters show significant differences at P = 0.05 according to the Fisher's least significant difference (LSD) test.

4. Discussion

Given the important roles that WRKY transcription factors play in response to various stresses, the traditional gene-by-gene research was not a high-efficiency method to study the plant that had no genome sequence. High throughput sequencing data have been used for functional gene mining and have proven to be an effective method for metabolic gene discovery and others [23]. In this study, the transcriptome dataset was searched for WRKY transcription factors in G. biloba and a total of 28 candidate WRKY genes were identified. Of these WRKY genes, we selected GbWRKY2, GbWRKY16, and GbWRKY21 to expression analysis. Interestingly, our data showed that the transcript level of GbWRKY2 was predominantly observed in ginkgo inflorescence and strongly induced by MeJA, implying GbWRKY2 might play dual roles in the development of ginkgo inflorescence and defense responses by mediating MeJA signaling.

4.1. GbWRKY2 Is a Group II WRKY Transcription Factor

A ginkgo gene (GbWRKY2) encoding a protein with sequence homology to members of the WRKY family has been characterized. This newly characterized gene is the first WRKY factor described in G. biloba and presents structural hallmarks that allow us to classify it within Group II of WRKY TFs [11]. The phylogenetic analysis also clearly showed that GbWRKY2 belong to Group II WRKY family. Numerous members of plant WRKY genes belong to Group II family and play roles in transcriptional reprogramming associated with resistance to various stresses [11]. A predicted nuclear localization signal (NLS) (Figure 4) strongly suggests that GbWRKY2 protein is translocated into the nucleus to control gene expression. These data suggested that GbWRKY2 might play an important role in defense response of ginkgo to biotic and abiotic stresses.

4.2. Multiple cis-acting Elements Response to Stress and Hormone in the Promoter Region of GbWRKY2

Stress-inducible gene expression is transcriptionally regulated by a change in the level and/or activity of sequence-specific DNA-binding transcription factors bound to specific cis-acting elements of promoter regions [54]. These regulatory factors are involved in the activation, suppression, and modulation of various signaling pathways in plant cells on biotic and abiotic stresses. Many plant promoters have therefore been identified and isolated, and genetic engineering in plants has been greatly enhanced using individual promoters [55]. Thus, we isolated a 1,363 bp-length promoter of GbWRKY2 (Figure 1S). Bioinformatics analysis showed that multiple cis-acting elements including fundamental and special elements associated with abiotic stresses and hormone regulations were found in the GbWRKY2 promoter (Table 3), indicating that GbWRKY2 gene might respond to various environment stimulus. Furthermore, a series of 5′ end deletion fragments of this promoter were detected using transient expression assays, which demonstrated that the activity of a truncated promoter from position −1 to −48 bp retained the ability to initiate the expression of GUS in transgenic tobacco leaves. This region is enough to keep the basic function of GbWRKY2 promoter. Bioinformatics analysis showed a TATA box was located in the region between −1 and −48 bp. Together taken into the results of bioinformatics and deletion analysis, we conclude that the region of −1 to −48 bp is the equal of core promoter and positions of TATA box correspond to the typical core promoter model [56]. Moreover, our experiments showed that deletion of the promoter regions between positions −1018 and −668 or between positions −288 and −137 caused very significant (P < 0.01) reductions in promoter activity suggesting that these regions likely contain potential transcription-enhancing cis-acting elements. Sequence analysis discussed above indicates that both regions contain three and two Dof TF binding sites, respectively, which may be important for the hormonal responsiveness of GbWRKY2 promoter.

4.3. GbWRKY2 Might Participate in the Development of Ginkgo Inflorescence

Similar to expression patterns observed in other plant species, three GbWRKYs were found to be expressed in all tissues we used, but at different expression levels. Moreover, the transcription of GbWRKY2 was observed abundant in flowers. In contrast, expression levels of GbWRKY16 were very low in flowers. And the expression levels of GbWRKY21 were significantly higher in leaves, stems, and female flowers than in roots and male flowers. The result may indicate that GbWRKY2, GbWRKY16, and GbWRKY21 played different roles involved in regulating plant developmental and physiological processes. The highest expression level of GbWRKY2 is in flowers while the lowest expression level of in stems, consistent with the spatial expression profile of ChWRKY2 from Corylus heterophylla [57]. Given highest transcript level of GbWRKY2 in flowers, it can be speculated that GbWRKY2 might play an important role in tolerance to low temperature in inflorescence, which developed in cold early spring. Thus, we deduced that GbWKY2 likely exhibited similar function of ChWRKY2 TF to participate in the developmental process of ginkgo inflorescence.

4.4. GbWRKYs Might Play Role in Stress-Related Signal Pathways

Salinity is an important abiotic stress factor, usually affecting plant growth, development, survival, and crop productivity. Thus, understanding the complex mechanism of salinity tolerance is important for agriculture production. Interestingly, several WRKY proteins were shown to be involved in plant salinity stress response. For example, the expression of CmWRKY17 was induced by salinity in Chrysanthemum morifolium and overexpression of CmWRKY17 in Chrysanthemum and Arabidopsis increased the sensitivity to salinity stress [58]. The transcripts of two closely related WRKY TFs (AtWRKY25 and AtWRKY33) from Arabidopsis were increased by NaCl treatment and both the Atwrky33 null mutants and Atwrky25Atwrky33 double mutants showed moderately increased NaCl sensitivity [59]. Poplar species increase expressions of transcription factors to deal with salt environments. Salinity increased heat-shock transcription factor (HSF) transcription in P. euphratica and PeHSF binds the cis-acting heat shock element (SHE) of the PeWRKY1 promoter, thus activating PeWRKY1 expression [60]. Similarly, the first evidence pointing towards a role for GbWRKY2 and GbWRKY16 in defense comes from the data showing that the GbWRKY2 and GbWRKY16 transcript is dramatically upregulated in ginkgo in response to NaCl. Further study on suppression/overexpression of GbWRKY2 and GbWRKY16 was required for unveiling the molecular mechanism of GbWRKY2 and GbWRKY16 gene participation in ginkgo tolerance to salt.

Temperature that exceeds an organism's optimal tolerance range is considered as an important abiotic stress factor. Tremendous work has been done in the past two decades to reveal the complex molecular mechanism in plants' responses to extreme temperature and there is increasing evidence that WRKY proteins are involved in responses to both heat and cold stresses. For example, a WRKY TF in Nicotiana tabacum responds to a combination of drought and heat stress [61]. Another example is that transgenic Arabidopsis plants overexpressing GmWRKY21 exhibited increased tolerance to cold stress when compared with wild-type plants [62]. In our studies, the expression levels of GbWRKY2, GbWRKY16, and GbWRKY21 were all repressed by heat stress. The expression level of GbWRKY2 was upregulated by cold stress and there was no significant effect of cold stress on GbWRKY16 transcript levels. In contrast, the expression level of GbWRKY21 was downregulated by cold stress. We also reported for the first time an increase of GbWRKY2 transcript level by cold but decrease by heat, consistent with the observation of cold responsive cis-elements (CRTDREHVCBF2 and MYC recognition site) (Table 3). Although low-temperature related WRKYs were isolated in several species [62–64]. The mechanism of how WRKYs respond to cold signals and regulated the expression downstream genes is still largely unknown. Further work is needed to elucidate the function of these important genes in low-temperature related signal pathways.

ABA is an important signal molecule related to abiotic stress. Previous studies had demonstrated that WRKY proteins may act as activator in ABA signaling [65]. It was reported that the expression of LtWRKY21 in Larrea tridentata was shown to function as an activator to control ABA-regulated expression of genes [66]. Recently, Sun et al. also [67] reported that 13 numbers of WRKY family in O. sativa were upregulated by ABA, indicating that these OsWRKY genes may play an important role in the response to abiotic stress, particularly as a key regulatory factor in ABA signaling pathway. MYBCORE, DPBF, and ABRE are known to involve in ABA and drought responses. Some MYBCORE, DPBF, and ABRE motifs were detected in the GbWRKY2 promoter by bioinformatic analysis (Figure 1S). The upregulated expression of GbWRKY2, GbWRKY16, and GbWRKY21 in ginkgo callus by ABA gave the direct evidence, suggesting that these WRKY genes probably function as key components during ABA signaling. Our results also showed that all three GbWRKYs were upregulated by ABA, indicating that these GbWRKY genes may participate in ABA signaling pathway responding to abiotic stress.

The upregulation of GbWRKY2 by SA is expected because three cis-elements (GT1 motifs) associated with SA were identified in the GbWRKY2 promoter region. Interestingly, GbWRKY2 also responds with a strong induction to a wide range of molecules such as MeJA and ETH, which constitute key signaling elements modulating defense responses to pathogens. This suggests that GbWRKY2 is a common component in the signaling pathways mediated by these hormones. Numerous studies report the induction of WRKY gene expression in response to SA and MeJA [13, 68, 69], but few analyses report the effect of other signal molecules such as ETH [38, 70]. Pathways involving MeJA and ET are considered to be mainly effective against necrotrophic pathogens, insects, and wounding, whereas those involving SA are more effective against biotrophs [71]. Thus, little attack of pathogens and insects in ginkgo may be due to the fact that WRKY protein, such as GbWRKY2, played important roles in defense responses by mediating SA, MeJA, and ETH signaling.

Taken together, GbWRKY2, GbWRKY16, and GbWRKY21 were activated by more than one type of stress condition. GbWRKY2 was observed to be upregulated in response to many different sources of stress, including salinity, ABA, SA, ETH, and MeJA treatment. GbWRKY16 was observed to be upregulated in response to salinity, ABA, SA, and ETH treatment. GbWRKY21 was observed to be upregulated in response to ABA, SA, and ETH treatment. GbWRKYs were upregulated in response to more than two types of stress which supported the occurrence of cross-talk between signal transduction pathways in response to different stress conditions in plants. Moreover, GbWRKYs displayed complex expression patterns in response to the stress. For example, GbWRKY2 and GbWRKY16 were upregulated at 3 hpt in response to salinity treatment and then downregulated quickly, demonstrating that GbWRKYs could be quickly and instantaneously responded to the stress. GbWRKY16 was not disturbed by the cold and MeJA treatment. GbWRKY16 was sustainably upregulated during the whole SA treatment. All of these showed that GbWRKYs played complicated and essential roles in defense in response to the stress.

5. Conclusion

This study presents the isolation and expression profile of the novel WRKY transcription factor gene GbWRKY2, which encodes a protein of 337 amino acid residues. The protein domain and phylogenetic analysis also showed that GbWRKY2 belong to Group II WRKY family. Bioinformatics analysis showed that multiple cis-acting elements including fundamental and special elements associated with abiotic stresses and hormone regulations were found in the GbWRKY2 promoter. Expression pattern analysis suggested that GbWRKY2 might play an important role in tolerance to salt and cold stresses and defense responses by mediating ABA, SA, MeJA, and ETH signaling. Studies on downstream function genes regulated by WRKY TF and mutual regulation between WRKY TFs in G. biloba have not been reported. On the basis of response abiotic adversity of GbWRKY2, we establish the binary overexpression vector of this gene. Studies on the genetic transformation of this gene in the callus of G. biloba are underway. This study will provide a basis to further reveal that the upregulated gene expression can strengthen the ability of plants to resist abiotic stress and identify some targeted genes regulated by WRKY TF in G. biloba. The present work on cloning and characterization of GbWRKY2 provided new clues for future studies on Ginkgo response to various stresses, such as sanity, drought, cold, and disease.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Nucleotide sequence of the 5'-upstream sequence of GbWRKY2. Various cis-elements were predicted from PlantCARE and PALCE plantforms. Coding region for GbWRKY2 gene is underlined, and translation start site is indicated by a translated methionine under ATG and shadowed. The transcription start site (TSS) and TATA-box are indicated as +1 and −26, respectively. Description of various cis-elements highlighted in the sequence is tabulated in Table 3.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (31370680), the Natural Science Foundation of Hubei Province (2013CFA039), Key Project of Chinese Ministry of Education (212112), International Science and Technology Cooperation Project of Hubei Province (2013BHE029 and 2013BHE039), Innovative Research Project of Ordinary University Graduate Student of China Jiangsu Province (2013CX2213-0551), and Foundation for Innovative Research Groups of Natural Science of Hubei Province (2011CDA117).

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Authors' Contribution

Yong-Ling Liao cloned and characterized GbWRKY2 gene and wrote the paper. Yong-Bao Shen screened the candidate transcripts of WRKY unigenes from transcriptome data. Wei-Wei Zhang and Jie Chang analyzed the qRT-PCR. Shui-Yuan Cheng performed the promoter analysis. Feng Xu designed the study and wrote the paper.

References

- 1.He X. Y., Huang W., Chen W., et al. Changes of main secondary metabolites in leaves of Ginkgo biloba in response to ozone fumigation. Journal of Environmental Sciences. 2009;21(2):199–203. doi: 10.1016/s1001-0742(08)62251-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deng Z., Wang Y., Jiang K., et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of a novel dehydrin gene from Ginkgo biloba . Bioscience Reports. 2006;26(3):203–215. doi: 10.1007/s10540-006-9016-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li L. L., Cheng H., Xu F., et al. Isolation and expression of the chloroplast copper/zinc superoxide dismutase gene (GbCuZnSOD) from Ginkgo biloba . Scientia Silvae Sinicae. 2010;46(6):35–42. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li L. L., Cheng H., Xu F., Wang Y., Chang J., Cheng S. Y. Molecular cloning, characterization and expression of iron superoxide dismutase gene from Ginkgo biloba . Journal of Fruit Science. 2009;26(6):840–846. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng H., Li L. L., Xu F., et al. Molecular cloning, characterization and expression of a manganese superoxide dismutase gene from Ginkgo biloba . Acta Horticulturae Sinica. 2009;36(9):1283–1290. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng H., Li L.-L., Xu F., Wang Y., Cheng S.-Y. Molecular cloning, characterization and expression of catalase1 gene from Ginkgo biloba . Forest Research. 2010;23(4):493–499. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng H., Li L. L., Xu F., et al. Cloning, characterization and expression analysis of a cytosolic ascorbate peroxidase gene (APX) from Ginkgo biloba . Journal of Fruit Science. 2013;30(2):214–221. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheng H., Li L. L., Wang Y., Cheng S. Y. Molecular cloning, characterization and expression of POD1 gene from Ginkgo biloba L. Acta Agriculturae Boreali-Sinica. 2010;25(6):44–51. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shen G., Pang Y., Wu W., et al. Molecular cloning, characterization and expression of a novel Asr gene from Ginkgo biloba . Plant Physiology and Biochemistry. 2005;43(9):836–843. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2005.06.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Banerjee A., Roychoudhury A. WRKY proteins: signaling and regulation of expression during abiotic stress responses. The Scientific World Journal. 2015;2015:17. doi: 10.1155/2015/807560.807560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rushton P. J., Somssich I. E., Ringler P., Shen Q. J. WRKY transcription factors. Trends in Plant Science. 2010;15(5):247–258. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2010.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Llorca C. M., Potschin M., Zentgraf U. bZIPs and WRKYs: two large transcription factor families executing two different functional strategies. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2014;5, article 169 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jiang Y., Yu D. WRKY transcription factors: links between phytohormones and plant processes. Science China Life Sciences. 2015;58(5):501–502. doi: 10.1007/s11427-015-4849-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Skibbe M., Qu N., Galis I., Baldwin I. T. Induced plant defenses in the natural environment: Nicotiana attenuata WRKY3 and WRKY6 coordinate responses to herbivory. Plant Cell. 2008;20(7):1984–2000. doi: 10.1105/tpc.108.058594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lai Z. B., Vinod K. M., Zheng Z. Y., Fan B., Chen Z. Roles of Arabidopsis WRKY3 and WRKY4 transcription factors in plant responses to pathogens. BMC Plant Biology. 2008;8(1, article 68):13. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-8-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wu X. L., Shiroto Y., Kishitani S., Ito Y., Toriyama K. Enhanced heat and drought tolerance in transgenic rice seedlings overexpressing OsWRKY11 under the control of HSP101 promoter. Plant Cell Reports. 2009;28(1):21–30. doi: 10.1007/s00299-008-0614-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shekhawat U. K. S., Ganapathi T. R., Srinivas L. Cloning and characterization of a novel stress-responsive WRKY transcription factor gene (MusaWRKY71) from Musa spp. cv. Karibale Monthan (ABB group) using transformed banana cells. Molecular Biology Reports. 2011;38(6):4023–4035. doi: 10.1007/s11033-010-0521-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen Y. Y., Yang S. G., Yang W., Tian W. M. Cloning and expression analysis of HbWRKY1 in the laticifer cells of rubber tree (Hevea brasiliensis Müll. Arg.) Chinese Journal of Tropical Crops. 2011;32(6):987–992. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kato N., Dubouzet E., Kokabu Y., et al. Identification of a WRKY protein as a transcriptional regulator of benzylisoquinoline alkaloid biosynthesis in Coptis japonica . Plant and Cell Physiology. 2007;48(1):8–18. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcl041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Xu Y.-H., Wang J.-W., Wang S., Wang J.-Y., Chen X.-Y. Characterization of GaWRKY1, a cotton transcription factor that regulates the sesquiterpene synthase gene (+)-δ-cadinene synthase-A. Plant Physiology. 2004;135(1):507–515. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.038612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ma D., Pu G., Lei C., et al. Isolation and characterization of AaWRKY1, an artemisia annua transcription factor that regulates the amorpha-4,11-diene synthase gene, a key gene of artemisinin biosynthesis. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2009;50(12):2146–2161. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcp149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Li S., Zhang P., Zhang M., Fu C., Yu L. Functional analysis of a WRKY transcription factor involved in transcriptional activation of the DBAT gene in Taxus chinensis . Plant Biology. 2013;15(1):19–26. doi: 10.1111/j.1438-8677.2012.00611.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sun Y., Niu Y., Xu J., et al. Discovery of WRKY transcription factors through transcriptome analysis and characterization of a novel methyl jasmonate-inducible PqWRKY1 gene from Panax quinquefolius. Plant Cell, Tissue and Organ Culture. 2013;114(2):269–277. doi: 10.1007/s11240-013-0323-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nakashima K., Fujita Y., Katsura K., et al. Transcriptional regulation of ABI3- and ABA-responsive genes including RD29B and RD29A in seeds, germinating embryos, and seedlings of Arabidopsis . Plant Molecular Biology. 2006;60(1):51–68. doi: 10.1007/s11103-005-2418-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kaplan B., Davydov O., Knight H., et al. Rapid transcriptome changes induced by cytosolic Ca2+ transients reveal ABRE-related sequences as Ca2+-responsive cis elements in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell. 2006;18(10):2733–2748. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.042713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ross E. J. H., Stone J. M., Elowsky C. G., Arredondo-Peter P., Klucas R. V., Sarath G. Activation of the Oryza sativa non-symbiotic haemoglobin-2 promoter by the cytokinin-regulated transcription factor, ARR1 . Journal of Experimental Botany. 2004;55(403):1721–1731. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erh211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Simpson S. D., Nakashima K., Narusaka Y., Seki M., Shinozaki K., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. Two different novel cis-acting elements of erd1, a clpA homologous Arabidopsis gene function in induction by dehydration stress and dark-induced senescence. Plant Journal. 2003;33(2):259–270. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01624.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luo H., Song F., Goodman R. M., Zheng Z. Up-regulation of OsBIHD1, a rice gene encoding BELL homeodomain transcriptional factor, in disease resistance responses. Plant Biology. 2005;7(5):459–468. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-865851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shirsat A., Wilford N., Croy R., Boulter D. Sequences responsible for the tissue specific promoter activity of a pea legumin gene in tobacco. Molecular and General Genetics. 1989;215(2):326–331. doi: 10.1007/bf00339737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xue G.-P. The DNA-binding activity of an AP2 transcriptional activator HvCBF2 involved in regulation of low-temperature responsive genes in barley is modulated by temperature. The Plant Journal. 2003;33(2):373–383. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2003.01630.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yanagisawa S. Dof1 and Dof2 transcription factors are associated with expression of multiple genes involved in carbon metabolism in maize. Plant Journal. 2000;21(3):281–288. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.2000.00685.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lopez-Molina L., Chua N.-H. A null mutation in a bZIP factor confers ABA-insensitivity in Arabidopsis thaliana . Plant and Cell Physiology. 2000;41(5):541–547. doi: 10.1093/pcp/41.5.541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hartmann U., Sagasser M., Mehrtens F., Stracke R., Weisshaar B. Differential combinatorial interactions of cis-acting elements recognized by R2R3-MYB, BZIP, and BHLH factors control light-responsive and tissue-specific activation of phenylpropanoid biosynthesis genes. Plant Molecular Biology. 2005;57(2):155–171. doi: 10.1007/s11103-004-6910-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Rubio-Somoza I., Martinez M., Abraham Z., Diaz I., Carbonero P. Ternary complex formation between HvMYBS3 and other factors involved in transcriptional control in barley seeds. Plant Journal. 2006;47(2):269–281. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313x.2006.02777.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhou D.-X. Regulatory mechanism of plant gene transcription by GT-elements and GT-factors. Trends in Plant Science. 1999;4(6):210–214. doi: 10.1016/S1360-1385(99)01418-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rose A., Meier I., Wienand U. The tomato I-box binding factor LeMYBI is a member of a novel class of Myb-like proteins. Plant Journal. 1999;20(6):641–652. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00638.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Abe H., Urao T., Ito T., Seki M., Shinozaki K., Yamaguchi-Shinozaki K. Arabidopsis AtMYC2 (bHLH) and AtMYB2 (MYB) function as transcriptional activators in abscisic acid signaling. Plant Cell. 2003;15(1):63–78. doi: 10.1105/tpc.006130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Agarwal M., Hao Y., Kapoor A., et al. A R2R3 type MYB transcription factor is involved in the cold regulation of CBF genes and in acquired freezing tolerance. The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 2006;281(49):37636–37645. doi: 10.1074/jbc.m605895200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mena M., Cejudo F. J., Isabel-Lamoneda I., Carbonero P. A role for the DOF transcription factor BPBF in the regulation of gibberellin-responsive genes in barley aleurone. Plant Physiology. 2002;130(1):111–119. doi: 10.1104/pp.005561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Elmayan T., Tepfer M. Evaluation in tobacco of the organ specificity and strength of the rolD promoter, domain A of the 35S promoter and the 35S2 promoter. Transgenic Research. 1995;4(6):388–396. doi: 10.1007/BF01973757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tjaden G., Edwards J. W., Coruzzi G. M. Cis elements and trans-acting factors affecting regulation of a nonphotosynthetic light-regulated gene for chloroplast glutamine synthetase. Plant Physiology. 1995;108(3):1109–1117. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.3.1109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Liao Z., Chen M., Gong Y., et al. A new geranylgeranyl diphosphate synthase gene from Ginkgo biloba, which intermediates the biosynthesis of the key precursor for ginkgolides. DNA Sequence. 2004;15(2):153–158. doi: 10.1080/10425170410001667348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu F., Cheng H., Cai R., et al. Molecular cloning and function analysis of an anthocyanidin synthase gene from Ginkgo biloba, and its expression in abiotic stress responses. Molecules and Cells. 2008;26(6):536–547. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Livak K. J., Schmittgen T. D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2-ΔΔCT method. Methods. 2001;25(4):402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.An S. H., Choi H. W., Hong J. K., Hwang B. K. Regulation and function of the pepper pectin methylesterase inhibitor (CaPMEI1) gene promoter in defense and ethylene and methyl jasmonate signaling in plants. Planta. 2009;230(6):1223–1237. doi: 10.1007/s00425-009-1021-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Jefferson R. A., Kavanagh T. A., Bevan M. W. GUS fusions: β-glucuronidase as a sensitive and versatile gene fusion marker in higher plants. The EMBO Journal. 1987;6(13):3901–3907. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1987.tb02730.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ramamoorthy R., Jiang S.-Y., Kumar N., Venkatesh P. N., Ramachandran S. A comprehensive transcriptional profiling of the WRKY gene family in rice under various abiotic and phytohormone treatments. Plant and Cell Physiology. 2008;49(6):865–879. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcn061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Liu X., Bai X., Wang X., Chu C. OsWRKY71, a rice transcription factor, is involved in rice defense response. Journal of Plant Physiology. 2007;164(8):969–979. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2006.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhou D.-X. Regulatory mechanism of plant gene transcription by GT-elements and GT-factors. Trends in Plant Science. 1999;4(6):210–214. doi: 10.1016/s1360-1385(99)01418-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Baumann K., De Paolis A., Costantino P., Gualberti G. The DNA binding site of the Dof protein NtBBF1 is essential for tissue-specific and auxin-regulated expression of the rolB oncogene in plants. Plant Cell. 1999;11(3):323–333. doi: 10.1105/tpc.11.3.323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yanagisawa S., Schmidt R. J. Diversity and similarity among recognition sequences of Dof transcription factors. Plant Journal. 1999;17(2):209–214. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1999.00363.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dong J., Chen C., Chen Z. Expression profiles of the Arabidopsis WRKY gene superfamily during plant defense response. Plant Molecular Biology. 2003;51(1):21–37. doi: 10.1023/A:1020780022549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Encinas-Villarejo S., Maldonado A. M., Amil-Ruiz F., et al. Evidence for a positive regulatory role of strawberry (Fragaria×ananassa) FaWRKY1 and Arabidopsis at WRKY75 proteins in resistance. Journal of Experimental Botany. 2009;60(11):3043–3065. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erp152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yong H. C., Chang H.-S., Gupta R., Wang X., Zhu T., Luan S. Transcriptional profiling reveals novel interactions between wounding, pathogen, abiotic stress, and hormonal responses in Arabidopsis . Plant Physiology. 2002;129(2):661–677. doi: 10.1104/pp.002857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Steffens N. O., Galuschka C., Schindler M., Bülow L., Hehl R. AthaMap: an online resource for in silico transcription factor binding sites in the Arabidopsis thaliana genome. Nucleic Acids Research. 2004;32(supplement 1):368–372. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zou Y. Y., Huang W., Gu Z. L., Gu X. Predominant gain of promoter TATA box after gene duplication associated with stress responses. Molecular Biology and Evolution. 2011;28(10):2893–2904. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msr116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhao T.-T., Wang G.-X., Liang L.-S., Ma Q.-H., Chen X. Cloning and expression analysis of ChWRKY2 from Corylus heterophylla under low temperature stress. Forest Research. 2012;25(2):144–149. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Li P., Song A., Gao C., et al. Chrysanthemum WRKY gene CmWRKY17 negatively regulates salt stress tolerance in transgenic chrysanthemum and Arabidopsis plants. Plant Cell Reports. 2015;34(8):1365–1378. doi: 10.1007/s00299-015-1793-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Li S., Fu Q., Chen L., Huang W., Yu D. Arabidopsis thaliana WRKY25, WRKY26, and WRKY33 coordinate induction of plant thermotolerance. Planta. 2011;233(6):1237–1252. doi: 10.1007/s00425-011-1375-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shen Z., Yao J., Sun J., et al. Populus euphratica HSF binds the promoter of WRKY1 to enhance salt tolerance. Plant Science. 2015;235:89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2015.03.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rizhsky L., Liang H., Mittler R. The combined effect of drought stress and heat shock on gene expression in tobacco. Plant Physiology. 2002;130(3):1143–1151. doi: 10.1104/pp.006858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zhou Q.-Y., Tian A.-G., Zou H.-F., et al. Soybean WRKY-type transcription factor genes, GmWRKY13, GmWRKY21, and GmWRKY54, confer differential tolerance to abiotic stresses in transgenic Arabidopsis plants. Plant Biotechnology Journal. 2008;6(5):486–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-7652.2008.00336.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wang L., Zhu W., Fang L. C., et al. Genome-wide identification of WRKY family genes and their response to cold stress in Vitis vinifera . BMC Plant Biology. 2014;14(1, article 103) doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-14-103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ling J., Jiang W. J., Zhang Y., et al. Genome-wide analysis of WRKY gene family in Cucumis sativus . BMC Genomics. 2011;12(1, article 471) doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-12-471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Antoni R., Rodriguez L., Gonzalez-Guzman M., Pizzio G. A., Rodriguez P. L. News on ABA transport, protein degradation, and ABFs/WRKYs in ABA signaling. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2011;14(5):547–553. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zou X., Shen Q. J., Neuman D. An ABA inducible WRKY gene integrates responses of creosote bush (Larrea tridentata) to elevated CO2 and abiotic stresses. Plant Science. 2007;172(5):997–1004. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2007.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sun L.-J., Huang L., Li D.-Y., Zhang H.-J., Song F.-M. Comprehensive expression analysis suggests overlapping of rice OsWRKY transcription factor genes during abiotic stress responses. Plant Physiology Journal. 2014;50(11):1651–1658. doi: 10.13592/j.cnki.ppj.2014.0286. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Caarls L., Pieterse C. M., Van Wees S. C. How salicylic acid takes transcriptional control over jasmonic acid signaling. Frontiers in Plant Science. 2015;6, article 170 doi: 10.3389/fpls.2015.00170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Tang Y., Kuang J.-F., Wang F.-Y., et al. Molecular characterization of PR and WRKY genes during SA- and MeJA-induced resistance against Colletotrichum musae in banana fruit. Postharvest Biology and Technology. 2013;79:62–68. doi: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2013.01.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zhang Q., Zhu J., Ni Y., Cai Y., Zhang Z. Expression profiling of HbWRKY1, an ethephon-induced WRKY gene in latex from Hevea brasiliensis in responding to wounding and drought. Trees. 2012;26(2):587–595. doi: 10.1007/s00468-011-0623-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Kunkel B. N., Brooks D. M. Cross talk between signaling pathways in pathogen defense. Current Opinion in Plant Biology. 2002;5(4):325–331. doi: 10.1016/S1369-5266(02)00275-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Nucleotide sequence of the 5'-upstream sequence of GbWRKY2. Various cis-elements were predicted from PlantCARE and PALCE plantforms. Coding region for GbWRKY2 gene is underlined, and translation start site is indicated by a translated methionine under ATG and shadowed. The transcription start site (TSS) and TATA-box are indicated as +1 and −26, respectively. Description of various cis-elements highlighted in the sequence is tabulated in Table 3.